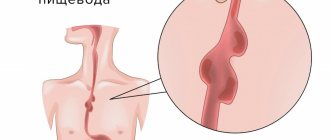

Before we begin to understand the symptoms of the disease, let's find out what it is and how it appears. Esophagitis is a whole group of diseases that are completely different from each other in their natural occurrence. But there is something that connects them all - inflammation of the mucous membrane of the esophagus.

Candidiasis is one of the diseases that affects the esophagus and is characterized by the Candida fungus. A very interesting fact is that candidal esophagitis has spread since the widespread use of antibiotics.

Today, many respiratory tract diseases are treated only with antibiotics, but these diseases can occur for various other reasons. So, we have a general idea of candidal esophagitis, let’s define the symptoms of the pathology.

Introduction

Recently, there has been a steady increase in malignant neoplasms of the esophagus, among which the leading positions are occupied by squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. We analyzed rare tumors of the esophagus for the period from 2000 to 2017, the incidence of which does not exceed 2% of the total number of tumors in this location and the morphological diagnosis of which can cause difficulties for pathologists. These tumors include primary melanoma of the esophagus, neuroendocrine and gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the esophagus, and granular cell tumor.

The data from the world literature, as well as our own observations at the Moscow Research Institute of Oriology named after. P.A. Herzen for the period from 2000 to 2022.

The most serious complication of GERD is Barrett's esophagus (Barrett's metaplasia), a disease that is a risk factor for the development of esophageal cancer (adenocarcinoma). The degeneration of mucosal cells in Barrett's esophagus occurs according to the type of so-called intestinal metaplasia, when ordinary cells of the esophageal mucosa are replaced by cells characteristic of the intestinal mucosa.

Intestinal metaplasia can turn into dysplasia (metaplasia and dysplasia are processes of cell degeneration that are successive in increasing severity of changes) and then develop into a malignant tumor. Therefore, Barrett's metaplasia is a precancerous condition, although esophageal cancer is a fairly rare disease, more common among men. The prevalence of Barrett's esophagus in the adult population is 8-10%. In addition to reflux disease itself, obesity is an independent risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. When both factors are present, the risk of developing adenocarcinoma increases significantly. However, the absolute risk of adenocarcinoma remains quite low even in people with severe reflux symptoms. Depending on the area of the esophagus where Barrett's metaplasia (and then, possibly, adenocarcinoma) develops, experts divide this disease into three types: metaplasia in the long segment of the esophagus, metaplasia in the short segment of the esophagus (3 cm or less from the junction of the esophagus) into the stomach) and metaplasia in the area of the cardial part of the stomach (the part of the stomach located immediately after the transition of the esophagus to the stomach). The prevalence of Barrett's metaplasia in the long segment of the esophagus according to endoscopic studies is about 1%. This percentage increases with the severity of GERD. This type of metaplasia is more common between the ages of 55 and 65 years, and is much more common in men (male to female ratio 10:1). Barrett's metaplasia in the short segment is more common, however, the prevalence of this disease is difficult to assess, since this type of metaplasia is difficult to distinguish endoscopically from metaplasia in the cardia of the stomach. At the same time, a malignant tumor with metaplasia in the area of the short segment of the esophagus and the cardiac part of the stomach develops less frequently than with metaplasia in the area of the long segment of the esophagus. Although it is clear that Barrett's metaplasia in the esophagus occurs against the background of GERD and sometimes leads to the development of esophageal cancer, it is not entirely clear why cells degenerate into the type of intestinal metaplasia in the cardiac part of the stomach. This type of metaplasia occurs in both GERD and gastritis in the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection. Moreover, according to research data, Barrett's metaplasia from the area of the cardial part of the stomach most likely develops against the background of gastritis even more often than against the background of GERD. However, intestinal metaplasia and inflammation in this area can appear in the absence of Helicobacter pylori, and in this case be a consequence of chronic reflux. The prevalence of this type of metaplasia is 1.4%. Although the direct cause of Barrett's metaplasia remains unclear, it is clear that metaplasia develops in the context of GERD and is associated with excessive pathological exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acid. Studies using pH monitoring have shown that patients with Barrett's metaplasia have a significantly increased incidence of reflux and duration of esophageal clearance. This may be due to a pronounced impairment of the contractile function of the esophageal muscles, which develops as a result of severe esophagitis. In addition, most patients with severe esophagitis have a hiatal hernia. In addition, manometric measurements in the region of the long segment of the esophagus with Barrett's metaplasia showed that there is a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and impaired peristalsis, similar to those in severe esophagitis. It remains unclear why some patients with severe esophagitis develop Barrett's metaplasia and others do not. There is an assumption that genetic predisposition plays a certain role. Barrett's Esophagus - Observation and Treatment In the treatment of patients with Barrett's esophagus, the main attention is paid to two points: treatment of GERD, against which metaplasia has developed, and prevention of the development of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. The principles of treatment for existing esophagitis and Barrett's metaplasia remain the same as for conventional GERD, taking into account that since there is a more pronounced effect of acid on the esophageal mucosa, therapy must be more intensive. Prescription of proton pump inhibitors is usually sufficient, however, surgery may be required if drug treatment is ineffective. Some experts, based on research data that have shown that cellular changes occur precisely due to the pathological effect of acid on the gastric mucosa, propose using drugs that suppress the secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach to treat Barrett's esophagus. However, it has not been clinically proven that the use of antisecretory drugs or antireflux surgery can prevent the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma or lead to the reversal of intestinal metaplasia. Thus, the main goal of treatment is the therapy of esophagitis. Since there are currently no known ways to prevent the development of Barrett's metaplasia, the doctor's actions should be aimed at reducing the risk of developing esophageal cancer. For this purpose, patients with Barrett's esophagus periodically undergo endoscopic examination with mandatory biopsy to determine the degree of degeneration of the cells of the esophageal mucosa (metaplasia or dysplasia; how severe). The timing of the examination is determined depending on the severity of the existing changes in the mucous membrane of the esophagus. So patients who have only Barrett's metaplasia without dysplasia are examined once every 2-3 years. If dysplasia is detected, a more thorough examination is carried out to determine the degree of dysplasia, since with high-grade dysplasia, cancer can develop within 4 years. Patients with low-grade dysplasia are prescribed a 12-week course of high-dose proton pump inhibitors, followed by a repeat examination with a biopsy. If the examination confirms the presence of low-grade dysplasia, then subsequent endoscopy is performed after 6 months, and then annually, if no development of high-grade dysplasia is noted. Surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus Surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus is aimed at reducing the number of episodes of reflux. Although reflux disease is a risk factor for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, it is not entirely clear whether the existence of Barrett's esophagus itself predisposes to the development of cancer or whether some other factors contribute to the malignant transformation of cells in the presence of Barrett's esophagus. Both medical and surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus helps to reduce the symptoms of the disease. However, according to research, even taking proton pump inhibitors in large doses does not reduce the frequency of reflux. Therefore, despite the improvement of patients' condition due to medication, surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus is of great importance. In addition, some studies show that the risk of developing esophageal cancer is significantly reduced after laparoscopic fundoplication compared with medical therapy. Although there is an increased risk of mortality after surgery, which is associated with an unexplained increase in the incidence of heart disease in such patients. In this regard, the decision about surgery is made by the doctor after carefully weighing all the arguments for and against surgical treatment. If the operation is performed by an experienced surgeon, the result can be very good, although it does not guarantee complete disappearance of the symptoms of the disease, which sometimes requires postoperative medication. Research data shows that drug therapy, as opposed to surgery, has less of an effect on the incidence of reflux during sleep. In this situation, both laparoscopic and open surgery are quite effective. In addition, according to some data based on long-term observations, after fundoplication the risk of developing dysplasia and esophageal cancer is lower than after drug therapy. Surgical treatment is also recommended for patients with Barrett's esophagus in combination with the presence of a hiatal hernia. Endoscopic ablation This method of surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus carries less risk of complications than major surgery. In theory, this method is relatively safe. The surgical technique consists of removing the affected part of the mucous membrane of the esophagus. At this site, the normal mucous membrane is subsequently restored, which reduces the risk of developing esophageal cancer. The affected part of the mucous membrane is removed using laser or other high-energy radiation. In this case, the patient is prescribed an additional dose of proton pump inhibitors in high doses to improve the restoration of the normal mucous membrane of the esophagus. The operation is performed either without preparation or after taking special medications that affect the cells of the altered part of the esophagus and prepare them for laser exposure to improve the result of the operation. Surgical treatment in the presence of high-grade dysplasia With high-grade dysplasia, the risk of developing adenocarcinoma also becomes high. Dysplasia can be found in only one area of the esophageal mucosa (focal), or can develop in several places at once (multifocal), and such dysplasia is associated with a significant risk of developing adenocarcinoma (27% within 3 years). In patients with Barrett's esophagus with a high degree of dysplasia, endoscopic ablation of the esophageal mucosa is not always advisable. This is due to the fact that with this approach it is quite difficult to completely remove the affected tissue, and with a high degree of dysplasia, the risk of developing esophageal cancer is also high, even if there is a small area of affected tissue. Therefore, there must be strict indications for endoscopic surgery. The risk of surgery must be carefully assessed. Endoscopic ablation is performed in patients who are not eligible for esophagectomy (major surgery in which part or all of the esophagus is removed). In other cases, esophagectomy remains the preferred method of surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus with a high degree of dysplasia. Esophagectomy is an effective treatment option in young and otherwise healthy patients, but carries a relatively high risk of mortality (3-10%). In this regard, some experts recommend continuous (high frequency) endoscopic monitoring instead of immediate surgery for high-grade dysplasia in patients with Barrett's esophagus. Because esophageal removal is a high-risk procedure, endoscopic ablation is used as an alternative surgical treatment for highly dysplastic Barrett's esophagus. This operation can be carried out thermally, chemically or mechanically. In any case, the operation consists of removing metaplastic or dysplastic epithelium in combination with intensive antisecretory therapy, which subsequently leads to the restoration of normal epithelium of the esophageal mucosa. Endoscopic resection of the esophageal mucosa This is another method of surgical treatment of Barrett's esophagus. The surgical technique consists of surgical excision of the affected part of the mucous membrane using special endoscopic instruments, including an electrocoagulator (which is used, for example, in endoscopic removal of polyps). The success of this operation is quite high, but often a relapse of the disease may develop within the first year after the operation. Thermal ablation is performed using an electrocoagulator, argon plasma coagulator or laser irradiation. One of the complications of this operation is perforation of the esophagus. Another ablation method is photodynamic irradiation using a special device. Like thermal ablation, this method can cause some side effects: chest pain, nausea and the development of esophageal strictures. In addition, patients should be warned that after surgery it is necessary to avoid prolonged exposure to the sun, as it is possible to develop a hypersensitivity reaction to ultraviolet radiation on the skin. This procedure is very effective and leads to the reversal of dysplasia in 90% of patients. Residual effects of Barrett's metaplasia are observed within 2-62 months in 58% of patients undergoing photodynamic ablation. Mechanical ablation involves mechanical removal of the altered part of the esophageal mucosa using special endoscopic instruments. This procedure is recommended for those patients who have an early stage of esophageal cancer and who, for one reason or another, cannot undergo major surgery (removal of the esophagus).

Primary melanoma of the esophagus

Traditionally, melanoma is considered in the group of skin tumors, since oncologists and pathologists most often encounter this localization in their routine work. Extradermal forms, according to various authors [3, 4], account for less than 1-1.5%. Melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract is a rare disease in comparison with other malignant tumors of this location. It accounts for less than 1% of all mucosal melanomas diagnosed in the world. The most common are primary melanomas of the oral cavity and anorectal area, with primary melanoma of the small intestine in third place [5].

Esophageal melanoma is more often metastatic than primary, which accounts for 0.1-0.2% of all malignant tumors of the esophagus and 0.18% of all melanomas of the mucous membranes. Only 300 observations have been described in the world literature so far. The annual incidence of this pathology is about 0.02–0.036 per 1 million population [5]. The peak incidence occurs in the sixth to seventh decade of life, and the ratio of affected men to women is 2:1 [1].

The initial clinical manifestations of the disease are scanty, have no specific features and become more pronounced in a later stage of the disease. Patients complain of dysphagia, pain in the epigastrium or behind the sternum associated with eating. Episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding and sudden, significant weight loss are characteristic of advanced stages of the disease.

At the time of diagnosis, metastases are detected in 30-40% of patients. The incidence of metastases in regional lymph nodes reaches 40-80%. The paraesophageal and celiac lymph nodes, as well as the mediastinal lymph nodes, are most often affected.

Hematogenous metastasis occurs mainly in the liver, lungs and brain [5].

The tumor is most often localized in the middle and lower third of the esophagus. In only 10% of all cases described in the literature, melanoma was found in the upper third of the esophagus. The tumor has the appearance of a single polypoid formation on a wide base, with a smooth or ulcerated surface, or a solitary flat formation, from light brown to black, depending on the pigment content. It is possible to detect “screenings” visible to the eye at some distance from the main tumor. In 25% of cases, esophageal melanomas are uncolored. Most often, the tumor grows exophytically, but there is a tendency for the tumor to spread longitudinally along the submucosa of the esophageal wall.

Histologically, esophageal melanoma is indistinguishable from cutaneous melanoma (Fig. 1).

Rice. 1. Melanoma of the esophagus. Rice. 1. Melanoma of the esophagus. There are epithelial cell, spindle cell, non-cell, and mixed variants of melanoma. It should be noted that esophageal melanoma often develops against the background of atypical melanocytic proliferation, and very often such areas are found adjacent to the invasive tumor, which confirms the primary rather than metastatic lesion.

To establish the diagnosis of primary melanoma of the esophagus, the method of immunohistochemical research helps, especially in cases where the diagnosis of melanoma is not unambiguous. In tumor cells, positive expression is detected with antibodies to Vimentin, S-100 protein, HMB-45, Melan-A, Tyrosinase in combination with the absence of expression of keratins and common leukocyte antigen (Fig. 2).

Rice. 2. Primary melanoma of the esophagus. Rice. 2. Primary melanoma of the esophagus.

The average life expectancy for primary esophageal melanoma is 10 months (range, 4-6 to 9-14.5 months). In MNIIOI them. P.A. Herzen for the period from 2000 to 2022, two cases of primary melanoma of the esophagus were diagnosed in women aged 59 years and 61 years. Both patients consulted a doctor at their place of residence with complaints of chest pain that appeared immediately after eating. During the examination, a tumor was detected in the middle third of the esophagus, and with a diagnosis of esophageal cancer, they were sent to our institute. With endoscopy and CT of the chest organs, the picture was assessed as leiomyosarcoma of the esophagus, emanating from the posterior right wall, without signs of penetration into the tissue. The operation involved a one-stage resection and plastic surgery of the esophagus with a gastric stalk with lymphadenectomy.

During the pathological examination of the surgical material in the lower third of the esophagus, a large, lumpy tumor of dark purple color with an ulcerated surface, measuring 2×1.5×1.5 cm, obstructing the lumen of the esophagus by ¾ of its circumference was visualized. Microscopic examination: malignant pigmented melanoma of a mixed epithelial-spindle-noncellular structure, with invasion of the muscular layer of the esophageal wall, areas of lentigo-melanoma at the edges of the tumor. No metastases were detected in 4 bifurcation, 3 tracheobronchial, 2 paraesophageal, 2 paratracheal lymph nodes. The diagnosis was confirmed by immunohistochemical study: positive expression of Melan-A and HMB-45 was detected in tumor cells.

Subsequently, three courses of immunotherapy were carried out. After 3 months, the patient had a relapse in the area of the postoperative scar, and therefore she was hospitalized at the Moscow Oncology Research Institute named after. P.A. Herzen.

Upon examination: in the projection of the upper third of the gastric graft, a pigmented formation with a diameter of up to 2 cm, with ulceration, and a violation of the integrity of the graft wall is determined. Metastatic lesions of the liver and spleen were revealed.

Three courses of PCT were carried out with some positive effect: the ulceration on the skin in the projection of the upper third of the gastric graft was epithelialized, and a decrease in the size of the liver metastasis by 25% was also noted.

However, a control ultrasound of the abdominal organs revealed an increase in the number and size of metastases in the liver up to 10 cm in diameter, the appearance of multiple nodular formations in the spleen with a diameter of up to 6 cm. In the area of the gastric graft stem there was a recurrence of ulceration, the appearance of areas of skin hyperpigmentation; upon palpation of the described area, there are two dense lymph nodes in the parastalk tissue, 0.5 cm in diameter.

A course of polychemotherapy was carried out, followed by surgery to the extent of: resection of the wall of the gastric graft, excision of parastalk tissue nodes. Histological examination revealed metastasis of melanoma of mixed structure.

The course of the postoperative period was complicated by the failure of the anastomotic sutures and the formation of a gastric fistula.

After 5 months, the patient died.

Damage to the esophagus

Non-penetrating injuries of the esophagus are subject to conservative treatment. The need for hospitalization and conservative therapy arises when deep abrasions of the mucous membrane and submucosal layer, accompanied by swelling of the peri-esophageal tissue, are detected during an X-ray examination or esophagoscopy. For superficial abrasions of the mucous membrane without reaction of the peri-esophageal tissue, patients can undergo outpatient treatment. They should be advised to eat a gentle warm diet, measure body temperature and immediately consult a doctor if pain when swallowing appears or increases, or if dysphagia, chills, or increased body temperature occur.

Conservative treatment of non-penetrating esophageal injuries is effective in the vast majority of cases. However, in 1.5-2% of patients, an abscess may form in the peri-esophageal tissue after 5-6 days, which requires surgical intervention.

Perforation of the esophagus by a foreign body is always accompanied by inflammation of the peri-esophageal tissue. This inflammation in the first hours and days after perforation is limited to a small area adjacent to the wall of the esophagus, and intensive antibacterial therapy started on the first day leads to recovery in most cases. Indications for drainage of a circumscribed abscess that occurs during antibacterial therapy occur in 5-8% of cases.

The presence of a foreign body in the lumen of the esophagus for more than a day leads to infection of this area and perforation of the esophagus under such conditions causes massive infection of the peri-esophageal tissue, often with non-clostridial anaerobic flora. The existence of an untreated purulent focus in the tissue of the neck or mediastinum for a day or more becomes extremely dangerous for the patient’s life, despite the small size of the damage to the esophageal wall. Attempts at conservative treatment of this type of damage are erroneous, since if surgical intervention is delayed, diffuse mediastinitis develops, sometimes ending in the death of the patient, despite subsequent adequate drainage of the purulent focus.

Thus, all patients are subject to surgical treatment if the foreign body was in the lumen of the esophagus for more than a day.

Instrumental and spontaneous ruptures of the esophagus require surgical treatment. In exceptional cases, when the risk of surgical intervention in a patient is extremely high (the patient has pneumonia, tuberculosis, purulent bronchitis, etc.), conservative therapy is possible provided there is a good outflow of purulent discharge from the mediastinum into the lumen of the esophagus (rupture of the esophageal wall no more than 1-1.5 cm, is not accompanied by damage to the mediastinal pleura, and the false passage in the mediastinal tissue does not exceed 2 cm). The listed conditions for conservative treatment provide for strict monitoring of the effectiveness of the therapy. Treatment consists of massive antibacterial therapy (thienam, amikacin), exclusion of fluids and food by mouth, infusion therapy and parenteral nutrition for 6-7 days.

Caution should be given against the use of such tactics in patients with diabetes mellitus. Considering the peculiarities of the course of purulent processes in this disease, any penetrating damage to the esophagus is subject to early surgical treatment.

When treating chemical burns of the esophagus, a complex of intensive conservative therapy is used. Emergency care consists of removing any remaining cauterizing liquid that has entered the stomach and neutralizing it. This is achieved by washing the stomach with a large amount of water, to which a solution of sodium bicarbonate is added in case of acid poisoning. It should be remembered that hasty and rough insertion of the probe into the stomach can itself lead to rupture of the esophagus.

Patients are prescribed antibacterial, infusion detoxification therapy, and painkillers. Steroid hormones are widely used, providing an anti-inflammatory effect and better tissue regeneration. Reparative processes are significantly improved by hyperbaric oxygenation sessions and local irradiation of the burn surface with a helium-neon laser through an endoscope. For burns of the lower third of the esophagus, application of adhesive compositions through an endoscope to the burn surface, which protects damaged tissues from the aggressive action of gastric juice, has a beneficial effect on healing.

However, in 10-15% of esophageal burns, scar strictures form within a year, which requires delayed surgical treatment.

Surgery

Surgical treatment of ruptures and perforations of the esophagus is a complex and difficult intervention. This treatment includes a complex consisting of endoscopic manipulations, surgical access, interventions on the damaged esophagus and techniques for draining the damaged area.

Surgical treatment is aimed at achieving the following goals:

1. Stopping the flow of infected contents through a defect in the esophageal wall into the mediastinum;

2. Adequate drainage of the purulent focus in the mediastinum;

3. Temporary exclusion of the esophagus from the act of digestion;

4. Providing the body’s energy needs through parenteral and enteral nutrition.

Resuscitation measures and preoperative preparation. Resuscitation measures include tracheostomy, the need for which arises due to stridor breathing during late admission of patients with perforation of the cervical esophagus, and drainage of the pleural cavity.

The pleural cavity should be drained if there is simultaneous damage to the esophagus and mediastinal pleura. Evacuation of fluid and gas from the pleural cavity before surgery prevents the occurrence of tension pneumothorax during induction of anesthesia and oxygen insufflation through a mask.

Patients admitted more than 2 days after esophageal perforation are severely dehydrated due to intoxication and the inability to take fluids orally. They have volemic disorders (hypotension, tachycardia, oliguria or anuria), without correction of which it is risky to begin surgical intervention. Such patients require short-term (no more than 2 hours) but intensive infusion therapy, including the introduction of electrolyte solutions, sodium bicarbonate, large molecular solutions and plasma.

Carrying out anesthesia during operations in patients with esophageal trauma has its own characteristics and difficulties, due, among other things, to the localization of injuries in the immediate vicinity of the tracheobronchial tree and mediastinal organs. Irritation of powerful reflexogenic zones and a rapid increase in intoxication create conditions for the occurrence of shock reactions. Significant swelling of the peri-esophageal tissues and extensive emphysema lead to respiratory distress and hypoxia. In this case, there is a real danger of compression of the upper respiratory tract and asphyxia.

A significant difficulty in carrying out anesthesia is the impossibility of preoperative emptying of the stomach using a probe, since an attempt to do so increases the gap, and the probe ends up in a false passage in the mediastinal tissue and even into the pleural cavity instead of the stomach.

In patients with esophageal rupture, endotracheal anesthesia with muscle relaxants is used. Oxygen saturation with a mask should be minimized, especially in cases of damage to the cervical and upper thoracic esophagus, since through a defect in the esophageal wall, lung gas penetrates into the mediastinum, increasing emphysema of the cellular spaces, and in the presence of a defect in the mediastinal pleura, increasing pneumothorax.

Endotracheal intubation in patients with esophageal injury is a responsible and difficult procedure. The presence of abrasions of the pharynx as a result of previous medical instrumental manipulations or independent attempts of patients to get rid of a foreign body, severe swelling of the epiglottis and paraligamentous space make it difficult to navigate during laryngoscopy. In this case, there is a real danger of inserting an endotracheal tube into the damaged esophagus.

When performing preoperative esophagoscopy and using a transcervical approach, the anesthesiologist must carefully monitor the position of the endotracheal tube, preventing its accidental displacement.

Surgical approaches. For injuries to the cervical and upper thoracic esophagus, transcervical access is used. If the intervention is limited to the neck area, the term used is collotomy. In cases where the surgeon penetrates the upper mediastinum, we are talking about transcervical mediastinotomy. Suturing a defect in the wall of the thoracic esophagus through cervical access is possible at the Th1 - Th2 level. This is explained by the narrowness of the surgical area, the inability to mobilize the esophageal wall well and apply sutures under visual control. It is possible to drain the posterior mediastinum from this approach along its entire length, up to the diaphragm, but in practice it is limited to the level of the tracheal bifurcation (Th4 - Th5).

An incision in the skin and subcutaneous muscle is made longitudinally along the anterior edge of the sternocleidomastoid muscle on the side of the esophageal injury (if the posterior wall is damaged, it is more convenient to use the left-sided approach). Then the thyroid gland with the trachea and recurrent nerve is moved medially, the sternocleidomastoid muscle and neck vessels are moved laterally and the lateral wall of the esophagus is widely exposed. If necessary, it is necessary to cross the scapulohyoid muscle and the inferior thyroid artery.

It should be remembered that in case of damage to the esophagus due to hematomas, edema and soft tissue infiltration, topographic-anatomical relationships may be changed, and therefore care must be taken during access.

Transpleural access is used to apply sutures to the thoracic esophagus, and to suturing the esophageal wall in the upper and middle thirds of the thoracic region, a right-sided lateral thoracotomy is used, and to suturing the esophageal wall in the lower third of the thoracic region, a left-sided lateral thoracotomy is used. If there are indications for resection of the damaged esophagus, a right thoracotomy is used.

Access to the thoracic esophagus is associated with possible injury to a whole complex of important structures: the posterior mediastinum, the aortic arch area, the pericardium, the root of the lung, the aortic plexus, the branches of the vagus nerve and the sympathetic trunk. With gross damage to this area, a number of severe complications arise, both during operations and in the immediate postoperative period.

After performing a thoracotomy, the lung is retracted anteriorly and the mediastinal pleura is exposed, which appears swollen and thickened, covered with fibrin. Sometimes it is literally separated from the esophagus by small gas bubbles. After careful isolation of the pleural cavity, the mediastinal pleura is opened in the longitudinal direction. In the later stages, the surgeon encounters a dense infiltrate, including the root of the lung and the main vessels of the mediastinum (azygos vein, descending aorta), which makes it difficult and even impossible to mobilize the esophageal wall for suturing and, especially, for resection. Therefore, this access is used in the early stages after esophageal rupture.

But even in the early stages, elderly and senile patients, the presence of severe concomitant diseases significantly increases the risk of transpleural intervention. In such cases, one should limit oneself to extrapleural drainage of the damaged area.

Transperitoneal access is the access of choice for ruptures of the lower thoracic and abdominal esophagus, including spontaneous ruptures.

In patients with undiagnosed spontaneous esophageal rupture, surgeons often perform an upper midline laparotomy for suspected perforation of a gastroduodenal ulcer. Not finding a perforated ulcer, the surgeon sutured the wound of the abdominal wall, not suspecting that he was close to establishing the truth. In such cases, it is always necessary to conduct a thorough inspection of the left subphrenic space. In the area of the esophageal opening of the diaphragm there may be hyperemia of the peritoneum, fibrin deposits, and tissue infiltration. If there is the slightest doubt, it is necessary to open the posterior mediastinum transhiatally along the wall of the esophagus and use a blunt forceps to go up a distance of 3-4 cm. If there is no rupture of the esophagus, this manipulation will remain without any consequences.

An important element of the transperitoneal approach for ruptures of the esophagus is the mobilization of the left lobe of the liver, without which manipulation at the level of the abdominal and lower thoracic parts of the esophagus is difficult.

After the assistant moves the stomach down and to the left, the surgeon, pushing the liver down with his left hand and stretching the left triangular ligament, grabs it with a long clamp. By pulling the clamp, the ligament is dissected under visual control over a distance of 10-12 cm, not reaching the dangerous area where the hepatic veins are located. The triangular ligament captured by the clamp must be ligated, since in rare cases a small bile duct passes through it, the intersection of which leads to the leakage of bile into the abdominal cavity.

After ligation of the ligament, the left lobe of the liver is retracted down and to the right, and the assistant holds it in this position with a large hepatic speculum. The second speculum is used to push the fundus of the stomach and spleen to the left. As a result, the area of the cardia and the esophageal opening of the diaphragm opens wide. The abdominal esophagus looks like a cord covered with peritoneum, continuing into the lesser curvature of the stomach; it is especially noticeable when the stomach is stretched.

Before dissecting the diaphragm, the inferior phrenic vein must be securely sutured and ligated on both sides of the intended incision. It is more convenient to begin suturing and ligating the distal segment of this large vein, located to the left of the intended diaphragm incision, because otherwise, its lumen will collapse and when stitching it, you can accidentally injure it. Pulling the threads like holders, the diaphragm is cut with pointed scissors from the anterior edge of the esophageal opening strictly anteriorly for 10-12 cm.

Sagittal diaphragmotomy, widely opening the mediastinum, allows sutures to be placed on the wall of the esophagus to the level of Th8 - Th9, depending on the patient’s constitution. In this case, vagotomy should not be performed unless absolutely necessary, especially of both trunks. When placing sutures on the wall of the esophagus and covering them with the bottom of the stomach, preliminary mobilization of the trunks of the vagus nerve is required.

The peculiarity of transperitoneal mediastinotomy for ruptures of the esophagus is the difficulty of layer-by-layer separation and dissection of tissue in the area of the esophageal opening of the diaphragm. Here an infiltrate of varying density is found, often spreading into the abdominal cavity along the lesser omentum, gastropancreatic ligament and lesser curvature of the stomach. In such cases, the wall of the esophagus serves as a reference point.

Serious complications that aggravate the prognosis are damage to the pleural layer or pericardium. The reasons for these complications are: 1) narrow surgical zone (small laparotomy, insufficient mobilization of the left lobe of the liver); 2) deviation to the left when performing sagittal diaphragmotomy; 3) excessive dissection of the diaphragm.

The most dangerous is the opened cavity of the heart sac, which will inevitably lead to pericarditis.

Interventions on a damaged esophagus. There are two options: suturing the defect in the esophageal wall and removing the entire altered esophagus.

The technique for suturing a rupture of the esophagus includes three sequential manipulations: detection of a defect in the esophageal wall and its mobilization, application of sutures and their covering with surrounding tissues.

Already in the first hours after perforation, emphysema, tissue swelling and fibrin deposits are detected in the damaged area. When used for diagnostic purposes, a suspension of barium sulfate is clearly visible and has the appearance of yellowish speckled spots that are visible through the edematous tissue. If difficulties arise, a solution of methylene blue can be injected into the lumen of the esophagus through a probe, which after some time enters the surgical wound.

To apply sutures to the wound of the esophagus, it is necessary to mobilize its wall. In this case, we must strive to preserve, firstly, the feeding vessels and, secondly, its connective tissue membrane (adventitia), which largely bears the load when suturing. Sutures on the wound of the esophagus should be applied in the longitudinal direction, because in this case, during contractions of the esophagus, they bear less load and are more reliable. In rare cases of transverse incised wounds or intersection of the entire esophagus, it is necessary to apply sutures in the transverse direction. In the presence of a laceration or gunshot wound with prolapse of the mucous membrane imbibed with blood, the latter is sparingly excised at the border of the unchanged mucosa. Some authors recommend excising the entire altered wall of the esophagus in the area of damage, but after this the size of the esophageal wound becomes much larger, which does not reduce the risk of suture failure, and if failure is avoided, a narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus occurs.

The most reliable are double-row interrupted sutures on an atraumatic needle. The inner row should be made of absorbable material (vicryl 2-0), the outer row should be made of monofilament non-absorbable material or long-term absorbable material (polydioxanone 2-0).

The first row of interrupted sutures is applied to all layers of the wall, inserting and puncturing the needle 3 mm from the edges of the wound. Each suture is tied with a knot inside the lumen, carefully matching the edges of the mucous membrane and avoiding excessive tightening. The application of this series is facilitated by a probe previously inserted into the lumen of the esophagus. The muscle layer is sewn together with the second row of sutures, tying knots on the outside.

The final and extremely important element of this operation is covering the suture line with surrounding tissue. For this purpose, a well-supplied tissue such as a pedunculated muscle flap is used. To cover the suture line of the cervical esophagus and the area of the upper thoracic outlet, the medial portion of the sternocleidomastoid muscle is cut out from the corresponding side; to cover the sutures of the thoracic esophagus with transpleural access, the intercostal muscle covered with the parietal pleura is cut out.

For the lower third of the thoracic and abdominal regions, the best way to cover the suture line is to create a cuff from the fundus of the stomach, such as a Nissen fundoplication, or cover it with a partially mobilized fundus of the stomach, such as a fundoraffia.

If possible, preference should be given to Nissen fundoplication, because the cuff not only reliably covers the suture line, but also prevents the reflux of aggressive gastric contents, which plays a large role in the genesis of suture failure in this area.

Resection of a damaged esophagus is a large and traumatic operation. In old and senile age, in the presence of severe concomitant diseases, resection of the esophagus, even if affected by a cicatricial process, should not be performed. The main task in such cases is to save the patient’s life, and all efforts must be directed toward the prevention and treatment of mediastinitis. The exception is patients who have had perforation of the esophagus affected by cancer. In these patients, in resectable cases, it is necessary to remove the esophagus, regardless of the age and severity of their condition.

Ensuring adequate drainage of the damaged area. The high mortality rate in esophageal ruptures is primarily due to the development of purulent mediastinitis. Until now, it reaches 20-50%, depending on the type of microflora, localization and prevalence of the purulent process.

The severity of mediastinitis is largely due to the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the posterior mediastinum. As is known, the mediastinum is a space difficult to access for the surgeon, containing vital organs and filled with loose fatty tissue, penetrated by a large number of nerve plexuses, lymphatic and blood vessels. Constant changes in the volume of the mediastinum during breathing, movements caused by the pulsation of the heart and aorta, peristaltic contractions of the esophagus, create a pump factor and contribute to the rapid spread of purulent infection.

Drainage of the mediastinum is most convenient and least traumatic when using narrow and long extrapleural approaches. However, independent outflow of pus through these channels is extremely difficult, and with transcervical drainage directed upward, it is impossible.

A solution was found in the use of the active drainage technique, when an antiseptic solution flows through one of the channels of a double-lumen drainage tube into the area of damage to the mediastinal tissue, and the contents are aspirated through the other. Constant vacuum in the area of damaged peri-esophageal tissue not only ensures complete evacuation of the products of inflammation and cell breakdown, but also contributes to the rapid collapse and obliteration of the cavity formed as a result of injury and surgery.

To ensure reliable evacuation of purulent exudate, the length of the drainage tract and its direction (up or down) do not matter much. Much more important for the effectiveness of this drainage method is the creation of tightness in the area of the drainage tubes, which is achieved by layer-by-layer suturing of soft tissues in the access area and removing them by punctures away from the sutured surgical wound.

When using transcervical access, one drainage, carrying one or two lateral holes, is installed at the site of the sutured defect in the esophageal wall, the second - along the entire length of the false tract.

When using transperitoneal access, one drainage is installed to the place where the esophagus is sutured and covered with a cuff, the second, control, is installed in the left subphrenic space to the esophageal opening of the diaphragm. This drainage is necessary to prevent the spread of pus throughout the abdominal cavity in the event of incompetence of the esophageal sutures. Both drains are placed over the liver and removed through punctures in the abdominal wall in the right hypochondrium. The area of diaphragmotomy and drainage is wrapped with a strand of the greater omentum. Providing enteral nutrition. During surgical treatment, the esophagus must be excluded from food passage for a long time. This is achieved either by inserting a soft nasogastric tube (in case of damage to the cervical and upper thoracic esophagus) or by applying a gastrostomy or jejunostomy.

If the defect of the lower thoracic or abdominal esophagus is sutured and adequately covered with a Nissen fundoplication cuff, the patient can be placed on a gastrostomy tube, since food introduced into the stomach will not enter the damaged area. A gastrostomy for nutrition is also applied in cases of resection of the thoracic esophagus. Typically, gastrostomy in these patients is temporary, so the simplest Kader technique is used.

If, due to some circumstances, it was not possible to perform a fundoplication that prevents the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus, a gastrostomy tube is used for aspiration of gastric juice, and a Meidl jejunostomy is applied for nutrition on a Roux loop that is turned off.

Postoperative period. The course of the postoperative period depends on the location and type of damage to the esophagus. When suturing defects of the cervical esophagus in the early stages after injury, the postoperative period proceeds smoothly.

With injuries to the thoracic esophagus, patients require complex intensive treatment aimed at preventing complications. Traumatic mediastinitis is extremely severe and its postoperative treatment requires the efforts of personnel over a long period of time.

For 3-5 days after surgery, great importance is attached to sufficient pain relief, especially with transpleural and transperitoneal approaches. Immediately after recovery from anesthesia, patients are given a semi-sitting position, constant sanitation of the tracheobronchial tree is carried out, and after transferring to independent breathing, sanitation of the oral cavity is carried out.

Complex intensive therapy includes antibacterial, immune, infusion-transfusion, detoxification therapy, which is carried out for other forms of generalized surgical infection, for example, peritonitis. If indicated, active detoxification methods are used (plasmapheresis, hemofiltration, etc.).

To a large extent, the success of surgical treatment of esophageal injuries is determined by adequate and reliable evacuation of infected contents from the mediastinum, from the pleural cavity and other areas involved in the traumatic process. The duration of lavage and aspiration depends on the timing of healing of the esophageal defect, the extent of destruction of mediastinal tissue and the length of the drainage canal.

In cases of preventive drainage in patients with sutured esophageal defects, the drains are removed on average 8-10 days after surgery.

With the development of purulent complications, lavage with aspiration through the drains sometimes continues for up to one and a half to two months, until the cavities in the mediastinum are obliterated, after which the drains begin to be gradually tightened and replaced with shorter ones.

This process requires daily comprehensive monitoring of the effectiveness of treatment, which includes clinical and immunological blood tests, as well as dynamic x-ray monitoring.

X-ray examinations are performed every 3-4 days during the first two weeks after surgery. It allows you to install:

1) condition of the walls of the esophagus (esophagitis, obstruction, suture failure); 2) the state of the mediastinal tissue (volume, infiltration, abscess formation); 3) the condition of the pleural cavities (effusion, encysted cavities); 4) condition of the lung tissue (atelectasis, inflammatory infiltration, abscess formation); 5) condition of the pericardial cavity (pericarditis); 6) the presence of communication between the esophagus and the tracheobronchial tree; 7) the size of the cavity in the mediastinum, its relationship to the wall of the esophagus, mediastinal pleura, diaphragm; localization of drains, their position in relation to the cavity in the mediastinum and the adequacy of its emptying when aspiration is connected.

Before discharging patients from the hospital, a control X-ray examination should be carried out, in which it is necessary to pay attention to the functional and morphological consequences of esophageal trauma in the form of strictures, occurring in 1.2% of cases, and post-traumatic diverticula, occurring in 3-4.8%.

Surgical treatment of the consequences of chemical and thermal damage to the esophagus is carried out in a delayed and planned manner. At the same time, the scope of interventions is very different - from bougienage of the esophagus and the placement of a gastrostomy for nutrition to complex reconstructive operations to create an artificial esophagus.

Neuroendocrine tumors of the esophagus

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) are considered rare neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The increased interest in this problem among morphologists is explained by the undoubted increase in their detection rate and the presence of many unresolved issues regarding terminology, clinical and morphological classification. However, NETs of the esophagus are extremely rare and account for approximately 0.04–0.05% of NETs from all locations, including the gastrointestinal tract [6]. Their frequency among all malignant tumors of the esophagus is 0.05–7.6% [1]. According to world literature sources [6, 7], no more than 100 cases of neuroendocrine carcinomas of the esophagus (NEC) have been described.

Despite such rare observations, in the WHO classification (2010), esophageal NETs are identified as an independent nosological form [1], which offers standard definitions of “neuroendocrine tumor” and “neuroendocrine cancer”. All well-differentiated neoplasms, regardless of whether they behave “benign” or give metastases, are designated as “neuroendocrine tumor” (NET), and they are graded G1 or G2. All low-grade neoplasms are called “neuroendocrine carcinoma” (NEC) and are graded G3. In accordance with the classification (WHO, 2010), to denote the entire group of tumors of this type, the term “neuroendocrine neoplasia” (neuroendocrine neoplasm - NEN) has been proposed, which unites tumors of all degrees of malignancy (low, intermediate, high).

NETs of the esophagus are detected in people aged 30 to 82 years, but more often in the sixth to seventh decade of life. The average age of patients is 56 years. Men are affected 6 times more often than women.

Most neuroendocrine tumors of the esophagus are highly differentiated, non-functioning and not accompanied by specific hormonal syndromes, rarely metastasize to the lymph nodes, are characterized by slow growth and therefore do not have a detailed clinical picture, often being an accidental finding. Sometimes, in more rare cases, they are combined with Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma [7]. Dysphagia, weight loss, and chest pain are the main symptoms of NET.

Esophageal NETs are usually localized in the lower third of the esophagus, which is most likely due to the large number of endocrine cells in this section. Relatively less often, a tumor is found in the middle third of the esophagus [8, 9].

Macroscopically, highly differentiated NETs are small, polypoid, and rarely ulcerated. Moderately differentiated NETs are larger in size and ulceration is more common. Carcinomas (NEC) are usually large, lumpy, dense, with deep infiltrative growth.

When examined microscopically, NET G1 consists of round monomorphic cells located diffusely or forming complexes of glandular structures in the form of “rosettes”, “palisades”, as well as cribriform structures. Tumor cells with a centrally located nucleus without polymorphism and mitosis with a peculiar “salt and pepper” chromatin structure. Unlike small cell carcinoma, there are no signs of necrosis or cell crush syndrome. In an immunohistochemical study, tumor cells give a positive reaction with chromogranin, synaptophysin, NSE, and cytokeratins. It should be noted that the index of proliferative activity of Ki-67 in well-differentiated NETs does not exceed 5%.

G2 NETs are histologically constructed from solid, acinar, trabecular structures. Tumor cells have more pronounced polymorphism with obvious numerous mitoses. Foci of necrosis are often present. These tumors also express neuroendocrine markers.

Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma (NEC) is an aggressive, infiltratively growing tumor, usually with simultaneous metastasis, built from small or large cells.

Large cell neuroendocrine cancer of the esophagus in the vast majority of cases is combined with Barrett's esophagus. Cells of large and medium size, with wide eosinophilic cytoplasm, low nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, the presence of nucleols. The small cell variant is indistinguishable from small cell lung cancer and accounts for 1% of all malignant tumors of the esophagus. Macroscopically, it is a large tumor, growing exophytically into the lumen of the esophagus, but infiltrative tumor growth can also be pronounced. Tumor cells with inconspicuous cytoplasm, hyperchromic nuclei with the presence or absence of small nucleoli form solid layers and nests. Noteworthy is the significant number of mitoses. In 50% of cases, focal squamous or glandular differentiation is observed. Necrosis and cell crush syndrome are detected. Tumor cells give a positive reaction with chromogranin, CD-56, P-53, and cytokeratins. Possible expression of NSE, synaptophysin.

Small cell esophageal cancer has a poor prognosis. Survival for this disease ranges from 6 to 12 months. In MNIIOI them. P.A. Herzen for the period from 2000 to 2022 diagnosed 48 neuroendocrine tumors of the esophagus, in 15 cases these were well-differentiated clinically inactive tumors.

We diagnosed large cell neuroendocrine cancer of the esophagus in 11 cases. The overwhelming majority were men aged 59 to 80 years. The average age of the patients was 69 years.

Small cell esophageal cancer was diagnosed in 22 cases. These were mostly men aged 49 to 77 years. The average age of the patients was 65 years.

In women, there were 3 cases of small cell esophageal cancer and 1 case of large cell cancer. The age of the sick women ranged from 49 to 79 years. About 2/3 of the patients did not show any complaints, and the other 1/3 of the patients complained of long-standing heartburn and chest discomfort associated with eating.

In all the described observations, the tumor was located in the lower third of the esophagus and looked like an exophytic node on a wide base, with a smooth gray surface, in some cases with ulceration on the surface. Microscopically, we most often observed the epithelioid variant of neuroendocrine tumors, represented by relatively monomorphic oval or round cells forming trabecular, rosette-like structures, as well as solid fields. The spindle cell variant of neuroendocrine tumors of the esophagus is much less common, according to our data, in no more than 1% of cases of all neuroendocrine tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. In poorly differentiated tumors, noticeable polymorphism, very high mitotic activity, the presence of necrosis, and “cell crush” syndrome are noteworthy. In each specific case, the diagnosis of a neuroendocrine tumor was confirmed by immunohistochemical examination.

Acute esophagitis

Morphologically, the following forms of acute esophagitis are distinguished: catarrhal, edematous, erosive, pseudomembranous, hemorrhagic, exfoliative, necrotic and phlegmonous. Depending on the size of the affected area, they can be focal or diffuse

- Catarrhal esophagitis

This is the most common form of acute damage to the esophageal mucosa. It is the result of the influence of almost all of the above etiological factors. Its substrates include swelling, hyperemia, and leukocyte infiltration of the esophageal mucosa.

Clinical manifestations of mild cases of catarrhal esophagitis consist of a feeling of rawness or burning behind the sternum while eating. Possible heartburn. These symptoms are very mild. The increasing severity of the process is characterized by their intensification, as well as the addition of retrosternal pain. These latter are perceived by patients as cutting, burning, piercing. The pain radiates to the neck, jaw, interscapular area and significantly intensifies when eating, which in some cases makes it impossible. The clinical picture is complemented by salivation, belching, and regurgitation of mucus. The general condition is usually not impaired.

In the vast majority of patients, the clinical picture of catarrhal esophagitis spontaneously disappears a few days after the onset of the disease.

- Erosive esophagitis

This disease is the result of the evolution of a previous form. As follows from the definition, its morphological feature is the presence of a significant number of erosions variable in size. The surface of the latter is covered with hemorrhagic exudate, pus, and fibrin deposits. Erosions can penetrate the submucosa. The surrounding tissue is hyperemic, edematous, and infiltrated with leukocytes.

The clinical picture of erosive esophagitis has much in common with the symptoms of the catarrhal form, but is more pronounced. In some cases, defects in the esophageal mucosa can serve as a source of bleeding, the intensity of which can be quite significant.

The prognosis of erosive esophagitis is usually favorable. This disease heals spontaneously once the cause that caused it is eliminated. Since superficial mucosal defects epithelialize with virtually no scar formation, stenosis of the esophagus is usually not observed. Complications, which primarily include massive bleeding and mediastinitis, are rare.

- Hemorrhagic esophagitis

This form occurs in severe infectious diseases accompanied by bacteremia (typhoid fever, sepsis, influenza, etc.). A characteristic feature of these forms of esophageal damage is a pronounced hemorrhagic background: pinpoint and focal hemorrhages in the mucous and submucosal membranes, hemorrhagic exudation. The latter determines the clinical picture of the present disease. Among the symptoms, melena, bloody vomiting, and regurgitation of mucus with a significant amount of blood come first. Profuse bleeding from the esophagus can often occur, which in some cases can be fatal. Against this background, the classic manifestations of esophagitis (dysphasia, retrosternal pain) seem to fade into the background.

The acute stage of the disease lasts 5-7 days, after which recovery usually occurs. Complications include massive bleeding and acute posthemorrhagic anemia. The prognosis of hemorrhagic esophagitis is largely determined by the severity of the underlying disease

- Pseudomembranous esophagitis

This form can occur during the course of diseases such as scarlet fever, diphtheria, etc., the distinctive feature of which is the presence of fibrinous exudate. A grayish film is formed from fibrin on the inner surface of the esophagus. It is easily removed because it is not intimately fused to the underlying tissues. The only exceptions are very severe cases of pseudomembranous esophagitis, in which fibrinous exudate also permeates the mucous and submucous membranes. Subsequently, long-term non-scarring erosions and ulcerations remain in place of the torn films.

The clinical picture of this form of esophagitis is dominated by dysphagia and intense retrosternal pain, which increases during eating. The release of fibrin films with vomit marks the beginning of the second stage in the development of the disease. At this time, in addition to the above symptoms, hemoptysis can be observed.

The severity of pseudomembranous esophagitis and its prognosis are determined by the underlying disease. Timely and qualified treatment of the latter contributes to the complete elimination of esophagitis, however, in a number of cases, a cicatricial stricture of the esophagus is formed.

- Exfoliative (membranous) esophagitis

This form occurs as a result of a chemical burn of the organ mucosa with concentrated acids or caustic alkalis, as well as complications of certain infectious diseases (pemphigus, smallpox, sepsis).

Exfoliative esophagitis is accompanied by the formation of multilayer fibrin films on the inner surface of the esophagus, which, unlike the previous form of the disease, have a strong connection with the underlying tissues. Rejection of these films causes extensive ulcerations of the mucous membrane, which in turn are the morphological substrate of esophageal bleeding of varying severity.

Manifestations of this form of esophagitis include dysphagia, chest pain and hemorrhagic syndrome. \

The prognosis of the disease in the vast majority of cases is favorable. Complications include abscess or phlegmon of the esophagus, perforation of its wall with the subsequent development of purulent mediastinitis. The outcome of exfoliative esophagitis can be esophageal stricture.

- Esophageal abscess

It is formed when the organ wall is injured by a foreign body. Symptoms of the disease consist of dysphagia and severe pain, most often localized in the upper third of the esophagus or behind the sternum in the projection area of the upper third of the esophagus. Signs of intoxication are mild; low-grade fever may occur.

A clinical blood test demonstrates neutrophilic leukocytosis with a shift to the left, an increase in ESR.

An X-ray examination makes it possible to visualize a round filling defect protruding into the lumen of the esophagus with smooth and clear contours with a diameter of 0.5 to 4 cm. Folds of the esophageal mucosa bend around this formation, which indicates its intramural location. Peristalsis of this area is not traced.

Esophagoscopy reveals local hyperemia, edema, and bulging of the organ wall. The opening of an abscess into the cavity of the latter is determined by the presence of thick pus, the discharge of which is enhanced by pressing on the abscess with the tip of the endoscope.

The course and prognosis of esophageal abscess are favorable. However, if it is opened not into the lumen of the esophagus, but into the mediastinum, then purulent mediastinitis inevitably develops. This complication dramatically worsens the patient’s condition and requires urgent surgical intervention.

- Phlegmon of the esophagus

It is also the result of traumatization of its wall by a foreign body (fish or chicken bone). However, due to the insufficiency of local protective factors or immunity, inflammation invades neighboring areas, as well as deeper layers, as a result of which periesophagitis and mediastinitis develop.

The general condition of such patients is serious. There are signs of intoxication. Body temperature is increased. Patients complain of intense pain in the chest or neck area, increased salivation, and vomiting. Upon examination, the swelling of the neck attracts attention. The mobility of the latter is limited due to severe pain. The head is slightly tilted to the healthy side. Palpation indicates pain on one or both sides.

X-ray of the esophagus demonstrates an asymmetric protrusion of one of its contours. The mucous membrane over it is thinned, peristalsis is not visible. The function of healthy parts of the esophagus is not impaired. Esophagoscopy can reveal hyperemia, edema and swelling of the esophageal mucosa at the site of phlegmon, from which foul-smelling pus is released. If suppuration of the esophagus involves its proximal parts, then a laryngeal speculum is used to examine the entrance to the organ.

A clinical blood test reveals neutrophilic leukocytosis with a shift to the left and an increase in ESR.

The disease is severe. Spontaneous recovery is unlikely. The risk of developing purulent mediastinitis is very high.

- Diffuse phlegmonous esophagitis

Most often caused by streptococci that have penetrated into the area of injury to the esophagus by a foreign body. In other cases, it is possible for purulent inflammation to spread to the esophagus from neighboring organs of the mediastinum or spine, which is observed with an abscess of the root of the lung, mediastinal lymphadenitis, phlegmon of the oral cavity, a malignant tumor of the esophagus or a chemical burn with concentrated acids and caustic alkalis.

The morphological substrate of this disease is purulent imbibition of the esophageal wall, melting of the submucous base and, as a consequence, detachment of the mucous membrane of the organ. The latter becomes necrotic and ulcerated in places. Usually the process occurs in the submucosal layer, but can penetrate deeper, reaching the serous membrane.

Diffuse phlegmonous esophagitis begins acutely. Dysphagia, salivation, persistent retrosternal pain appear, aggravated by swallowing and coughing. The intensity of such pain is often so significant that patients try to avoid drinking water or food. The addition of vomiting may result in the release of areas of rejected esophageal mucosa of various sizes.

Severe intoxication leads to disruption of the general condition of such patients (chills, fever, weakness, anorexia).

Due to the threat of esophageal rupture, X-ray examination is not performed in the acute phase of phlegmonous esophagitis. After the intensity of the disease subsides, its x-ray semiotics is characterized by the eroded contours of the esophagus and the absence of folding of the mucous membrane. The latter is covered with multiple ulcers, as indicated by filling defects of various shapes and sizes. The lumen of the esophagus is unequal in width and is filled with mucopurulent contents. The walls of the organ are hypotonic, peristalsis is sluggish or absent altogether.

The prognosis of the disease is serious. Even promptly started massive antibacterial therapy does not always have the expected result. Phlegmonous esophagitis gives a very high percentage of complications. In such patients, cases of spontaneous pneumothorax, as well as pleural empyema, periesophagitis, mediastinitis, and mediastinal abscess have been described.

The clinical picture of the latter resembles acute sepsis. The patient's general condition suddenly and sharply deteriorates (oppressive weakness, chills, hectic fever, blackout), dysphagia and retrosternal pain increase. Excessive gas formation due to the proliferation of anaerobic infection leads to the formation of subcutaneous emphysema. The process can give expansion to nearby organs (thyroid gland, aorta, spine, pleura, lungs, border sympathetic trunk) and cause severe damage to the latter.

Mediastinitis and mediastinal abscess are usually fatal. Their spontaneous healing observed in rare cases through the breakthrough of an abscess into the lumen of the esophagus or into the bronchial tree belongs to the field of casuistry. It is possible to encapsulate an abscess in the mediastinum, but this is fraught with serious consequences for the patient. The prognosis of this disease is unfavorable.

X-ray semiotics of purulent mediastinitis is characterized by an expansion of the mediastinal shadow, an increase in the prevertebral space, a decrease in tracheal mobility during breathing, and mediastinal emphysema. Mediastinal abscesses are diagnosed based on the presence of a cavity with a fluid level.

A clinical blood test reveals neutrophilic leukocytosis (hyperleukocytosis) with a shift to the left, toxogenic granularity of leukocytes, and a significant increase in ESR.

Some cases of phlegmonous esophagitis may be accompanied by arrosion of a blood vessel with the development of profuse esophageal bleeding.

Despite adequate treatment of phlegmonous esophagitis, such patients usually have residual defects in the form of one or even several cicatricial strictures of the esophagus. These latter require appropriate correction in the future.

- Necrotizing esophagitis

This is the most severe form of acute inflammatory lesions of the esophagus. It develops in weakened patients as a complication of certain infectious diseases or pathological conditions (scarlet fever, measles, typhoid, sepsis, smallpox, candidiasis, agranulocytosis, uremia and some others).

A distinctive morphological feature of necrotizing esophagitis is the necrosis of large areas of the esophageal mucosa, accompanied by their rejection and the formation of deep, long-term non-healing ulcers. At the same time, there is abundant exudation of a bloody or purulent nature.

The clinical picture of necrotizing esophagitis is characterized by the fact that, against the background of symptoms of the underlying disease, which initially determines the severity of the patient’s condition, dysphagia, intense chest pain when swallowing, and vomiting appear. Fragments of necrotic esophageal mucosa are often found in the vomit. Complications of this form of acute esophagitis include profuse bleeding, perforation of the esophageal wall with the development of purulent mediastinitis or mediastinal abscess.

The prognosis of necrotizing esophagitis is extremely serious. Healing in almost all cases is accompanied by cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus.

Abrikosov's tumor

Granular cell tumor, or Abrikosov’s tumor, was identified as an independent nosological unit by A.I. Abrikosov in 1925 in a report at the All-Russian Congress of Pathologists in Moscow. In 1931, he was the first to diagnose lesions of the larynx and esophagus and noted the possibility of malignant degeneration.

Granular cell tumor was previously included in the group of myogenic tumors on the basis of some morphological similarity of its cellular elements with embryonic muscle cells. Subsequently, a number of studies appeared, based on the results of which it was hypothesized that granular tumor cells most likely originate from the nerve sheath, and not from the muscles. J. Garancis in 1970 suggested that granule cells are a type of Schwann cells. The origin of the tumor from Schwann cells was also confirmed by other authors, who discovered the expression of basic myelin protein (S100) and other proteins of myelin fibers of peripheral nerves in tumor cells; muscle proteins, on the contrary, were not always detected [10, 11].

Most often, Abrikosov's tumor occurs in adults 30–60 years of age, with the peak of the disease occurring at 39 years of age. Women are affected three times more often than men. Abrikosov tumors in children are casuistically rare [10]. Granular cell tumor most often affects the skin and oral mucosa [11, 12]. As a rule, these tumors are single lesions, but in 10% of cases there are also multiple lesions, which can be synchronous or metachronous. The gastrointestinal tract is rarely affected, in only 6-10% of cases, but in most cases (30-60%) the tumor was found in the esophagus [13].

In 65% of cases, the tumor is localized in the lower third of the esophagus. The middle and proximal third of the esophagus are affected in 20 and 15% of cases, respectively. Clinical manifestations of granular cell tumor of the esophagus do not have any specific features, but have a direct relationship with the size of the tumor node. Thus, tumors that do not reach 10 mm in size can be asymptomatic and be an incidental finding when examining a patient for another gastrointestinal pathology [14]. When the tumor enlarges more than 10-20 mm, patients usually complain of dysphagia and chest pain.

Macroscopically, the tumor has the appearance of a single tumor node of dense consistency, located in the submucosal layer of the esophageal wall. On the section, the tumor is yellowish-gray in color, with an infiltrative type of growth. The mucous membrane is involved in the process. Particular attention should be paid to the fact that the tumor in most cases is benign, despite the infiltrative type of growth. Malignant variants are extremely rare.

On microscopic examination, the tumor is represented by polygonal epithelial-like and elongated spindle-shaped cells with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing phagolysosomes. The cells contain centrally located, small pyknotic nuclei (Fig. 3).

Rice. 3. Abrikosov tumor. Rice. 3. Abrikosov tumor.

Immunohistochemical examination plays an important role in making the diagnosis of granular cell tumor. In accordance with its neurogenic origin, Abrikosov’s tumor gives a positive reaction with Schiff’s acid (CHI reaction), expresses S100, nestin, CD-68 and does not express smooth muscle actin, desmin, CD-117, CD-34 [13]. According to recent studies, it is recommended to additionally use Ki-67 to classify a tumor as benign, atypical or malignant.

Malignant granular cell tumors, as mentioned above, are extremely rare. According to world literature, they occur in only 1-2% of all cases of granular cell tumors. However, identifying evidence of malignancy is important because of the potentially aggressive behavior of these tumors and the poor prognosis associated with metastatic disease.

In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al. proposed 6 histological criteria for distinguishing benign from atypical or malignant granular cell tumors. These histologic criteria are defined by the following characteristics: increased nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear pleomorphism, presence of vesicular nuclei with prominent nucleoli, tumor necrosis, spindle cell structure, and increased mitotic activity. Tumors with a combination of 3 or more of these criteria should be classified as malignant, while tumors with 1-2 criteria are classified as atypical. Tumors that do not meet any of the proposed criteria are benign.

Endoscopic resection is considered a safe and effective treatment option for esophageal granular cell tumor. Relapses of the disease after radical removal are extremely rare. Atypical and malignant variants of Abrikosov’s tumor have a worse prognosis and require more careful examination and monitoring of the patient.

We observed a granular cell tumor of the esophagus in a 46-year-old man.

Over the course of a year, the patient noted the appearance of discomfort and chest pain after eating, and therefore consulted a gastroenterologist at his place of residence. According to the results of an endoscopy, a formation in the lower thoracic esophagus with a diameter of up to 0.5 cm was revealed.

Over the next 5 years, he was regularly monitored. During the next control EGD study, the formation in the esophagus increased in diameter to 2 cm. He independently contacted our institute.

According to the results of the examination at the Moscow Scientific Research Institute named after. P.A. Herzen, with CT scan of the chest cavity - in the retropericardial segment of the esophagus, along the right wall, a polypoid formation, 1.6x1.5 cm in size, is determined, protruding into the lumen of the esophagus, infiltrating all layers of its wall. Endoscopically and endosonographically - a picture of a nonepithelial tumor of the lower thoracic esophagus with signs of invasion of the submucosal layer, enlargement of paraesophageal lymph nodes of unknown origin.

Laparoscopic resection of the esophagus was performed. Macroscopically, in the esophagus 34 cm from the incisors on the front wall, a submucosal tumor is visualized, moderately mobile, dense, up to 2 cm in size, the mucous membrane above it is loosened and hyperemic.

Histological examination, taking into account immunohistochemical studies, diagnosed a granular cell tumor (Abrikosov tumor).

The postoperative period was without complications.

He was discharged in satisfactory condition under the supervision of an oncologist and surgeon at his place of residence. At follow-up examinations after 3 and 6 months, there were no signs of relapse.

Causes of the disease

Fungus of the genus Candida as a cause of candidal esophagitis

As we have already said, the causes of this disease can be very different. The fungus candidiasis esophagitis can function on almost all tissues of the human body. One of the most common causes is disruption of the body’s gastrointestinal tract, or more precisely, its tissue component.

In most cases, this occurs after long-term treatment with antibiotics, which kill almost all bacteria, thereby creating favorable conditions for the development of candidiasis on the mucous membrane of the esophagus.

There is also a high likelihood of developing candidal esophagitis in those who suffer from alcohol addiction or simply drink alcohol very often. Those who often take hormonal drugs, and in particular, contraceptives, are also at risk of this disease.

As you can see, in most cases, candidal esophagitis occurs as a result of taking certain medications (antibiotics, birth control pills). This does not mean that you need to stop taking these drugs, just be careful and not get carried away with them. If it is possible to replace antibiotics with another remedy, then it is better to do so.

If you can do without birth control pills and choose another type of protection, then do that too. In any case, this is not a complete list of the causes of this disease, since they can be very diverse and often you cannot even predict this disease.

Esophageal GIST

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are the most common mesenchymal tumors of the gastrointestinal tract. According to various authors [15], they make up from 0.1 to 3% of all malignant neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract and can be localized in any part of it - from the esophagus to the anus, but most often these tumors are found in the stomach (50-60%) and in the small intestine (30-40%).

In 1998, L. Kindblom et al. found that GIST develops from the interstitial cells of Cajal, which form a network in the muscular layer of the gastrointestinal tract wall and regulate its autonomic motor activity, i.e., they are pacemaker cells that provide communication between smooth muscle cells and nerve endings [16, 17]. Currently, GISTs include mesenchymal tumors, the cells of which have a positive immunohistochemical reaction to CD-117 and CD-34, DOG-1.

GISTs develop in people over 40 years of age and do not have a gender predisposition. The average age of patients is 55-65 years. Before the age of 40, these tumors are found extremely rarely. All GISTs are considered potentially malignant. Studies have shown that neither gender nor primary tumor location affects overall survival [16].