Introduction

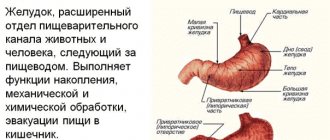

Heterotopia, i.e. atypical localization, of the gastric mucosa (GM) can occur in any part of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), including the rectum and gallbladder. Heterotopy of the coolant in the upper parts of the esophagus, which in the English-language literature is known under the term “inlet patch”, is an island of ectopic mucosa, characteristic of the stomach, in the proximal esophagus at the level of the upper esophageal sphincter or several centimeters distal (Fig. 1, 2) [1]. In rare cases, heterotopia loci are found in all parts of the esophagus [2, 3].

The first case of detection of glands containing parietal cells in the upper esophagus was described in 1805 by pathologist Schmidt [1]. Thanks to the development of endoscopic technologies, the understanding of this problem has now been significantly expanded, but many issues still remain poorly understood. In particular, researchers disagree significantly about the frequency of inlet patches. Thus, according to autopsies, heterotopia of the coolant in the proximal esophagus occurs in 0.7–70% of cases [1], according to endoscopic studies, the frequency also varies widely and ranges from 0.1% to 14.5% [4–6 ].

Information about the features of the development of esophageal heterotopia of the coolant depending on age and gender is ambiguous. H. Takeji et al. [1] believe that the lesion can regress with age, and note its higher frequency in males. The work of other researchers does not demonstrate significant age-gender differences [7].

Pathogenesis and pathomorphology

The pathogenesis of heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus is unknown. Three hypotheses for the development of this pathology have been proposed. Most authors are of the opinion that the “inlet patch” is of congenital origin [8, 9]. At the 11th week of embryogenesis, the columnar epithelium is replaced by stratified squamous epithelium, spreading in the distal and proximal directions from the middle part of the esophagus, with the proximal portion of the esophagus being the last to undergo transformation [8]. This theory is confirmed by the following facts: firstly, immunohistochemical analysis has shown that heterotopic loci contain cells characteristic of the embryonic GM [8, 10]; secondly, the prevalence of heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus does not increase with age, and, according to some data, is more common in children [8].

Another theory suggests an acquired nature of metaplastic transformation of the squamous epithelium due to chronic acid exposure in gastroesophageal reflux, similar to the development of Barrett's esophagus [11].

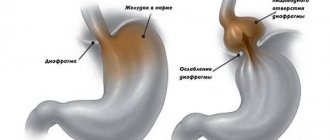

The rupture of retention cysts of the glands of the epithelium of the proximal esophagus is considered as another variant of the origin of heterotopia of the gastric esophagus (Fig. 3, 4) [12].

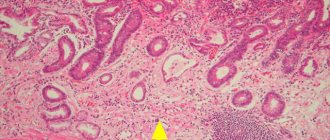

Most often, the epithelium in the ectopic locus corresponds to the fundic and cardiac histological types, less often to the antral (Fig. 5). In a study by U. Peitz et al. [6] it was noted that the cardiac type of epithelium is characteristic of small heterotopias, while the fundic type is more common in large heterotopias. It is significant that the “inlet patch”, in the presence of parietal cells, can produce a certain amount of acid (Fig. 6) [13]. It should be noted that the anatomical proximity to the laryngeal mucosa and its high sensitivity to acid damage, even with weakly acidic secretion, can lead to symptoms. In addition, mucus production, even in the absence of acid, has been shown to induce laryngopharyngeal symptoms [14]. Hyperacidity can also induce chronic inflammation and ulceration of the esophageal mucosa located around the area of ectopic coolant, and is a rare cause of the development of strictures. Morphologically, the inlet patch is often associated with inflammatory infiltration of granulocytes and plasma cells. Other histological changes include atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia and adenocarcinoma [8]. In 2004, BH von Rahden proposed a classification that made it possible to structure the morphological and clinical manifestations of heterotopia of the coolant (Table 1) [2].

Areas of heterotopia can be colonized by Helicobacter pylori

(Нр) [4]. The prevalence of Helicobacteriosis in foci of coolant ectopized into the esophagus reaches 82% [11]. Infection rates are likely to correlate with the prevalence of Hp infection in the general population. Although the role of HP in this situation remains unclear, it can be assumed that it can cause changes similar to those observed in the stomach: atrophy, metaplasia, dysplasia and carcinoma [8].

Diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus

Method for assessing the barrier function of valves of hollow organs in abdominal surgery

Barrett's esophagus is diagnosed by endoscopic examination of the esophagus and stomach. The study is carried out using a video esophagogastroscope with NBI or chromoscopy with taking a biopsy from at least 4 areas. The preparations are subjected to histological or immunohistochemical examination. In this case, visually in the lower third of the esophagus, changes in the mucous membrane with a bright red color are determined as “tongues of flame.”

The height of changes in the mucosa (the length of Barrett's esophagus) can be of three types: short - when the length of the affected area is less than 3 cm, medium - 3-5 cm and long - more than 5 cm. It is very important to understand the degree and type of dysplastic changes in the changed mucosa (classification P H. Riddell (1983)).

It is worth emphasizing that in order to examine such a delicate area as the lower third of the esophagus and the cardia of the stomach, assessing the condition of the gastroesophageal junction area and the function of the lower esophageal sphincter, the patient must be in a calm state and the absence of antiperistaltic contractions due to the gag reflex. As many authors say, complete “internal calm on the deck of a ship when there is a storm in the ocean” is necessary. Therefore, the use of short intravenous sedation makes it easier for the patient to tolerate the procedure and allows the doctor to make a more accurate diagnosis. In our clinic, we offer patients videofibroscopy using ambulatory anesthetics made in the USA.

In recent years, histologists have begun to note that material taken from one section of Barrett's esophagus may correspond to different types of dysplasia: intestinal metaplasia, gastric metaplasia, or cardiac type of metaplasia. Thus, two or three types of epithelium may occur in one section of the esophagus. This occurs as a result of pathological reflux of aggressive stomach contents into the esophagus (bile or acid) and the sequential restructuring of the esophageal epithelium, first into the cardiac one, and then into the intestinal one. Moreover, this situation is observed in 30% of patients. From a practical point of view, it is important to understand, this is based on large groups of studies, that the type of dysplasia does not affect the rate of degeneration into cancer. In this regard, indications for complex surgical treatment should be given in the presence of proven Barrett's esophagus, regardless of the type and stage of dysplasia.

It is worth noting that in 70% of cases, Barrett's esophagus develops against the background of a hiatal hernia (HHH) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) without a HHH. Therefore, in order to make an accurate diagnosis and, most importantly, understand the reasons for the development of this condition, we must have maximum information about the condition of the upper gastrointestinal tract. With this in mind, it is entirely necessary to perform esophagogastroscopy, in which to assess the condition of the mucous membrane of the esophagus and stomach, take a biopsy from several points (area of pronounced changes) and determine the extent of changes in the mucous membrane of the esophagus in centimeters, as well as detect the presence of bile in the stomach and assess the condition of the pylorus. Next, it is necessary to perform daily pH measurements of the esophagus and stomach to clearly understand the type of pathological reflux: acidic or alkaline. Then carry out an X-ray examination of the esophagus and stomach, during which it is possible to make or reject the diagnosis of hiatal hernia, as well as analyze the evacuation from the stomach and detect the phenomena and degree of duodenostasis.

This information forms the basis for choosing an algorithm for individual treatment of a particular patient.

To identify the hiatal hernia, determine the type of metaplasia and the degree of damage to the esophagus, as well as select the correct individual tactics for surgical treatment, you must send me a complete description of gastroscopy with a biopsy of the esophagus from at least 4 points, an x-ray of the esophagus and stomach with barium for the hiatus, preferably an ultrasound. abdominal organs, it is necessary to indicate age and main complaints. In rare cases, if there is a discrepancy between complaints, X-ray data and FGS, it is necessary to perform daily pH-metry and manometry of the esophagus. Then I will be able to give a more accurate answer to your situation.

Diagnostics

The main method for diagnosing heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus is esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy. Unfortunately, heterotopic lesions are often missed during endoscopy because the proximal esophagus is either ignored or skimmed over [15]. This fact probably explains the significant difference in prevalence data obtained from autopsy and endoscopic studies. With endoscopy, areas of the coolant in the proximal esophagus are visualized as round or oval spots of salmon color, velvety appearance, often single, less often paired and multiple. The surface may be smooth or grainy, flat or slightly raised. Infrequently, ectopic coolant is an area of mucosal depression. Most inlet patches are located on the lateral walls, usually a few centimeters distal to the upper esophageal sphincter (16–21 cm from the incisors). Dimensions can vary from microscopic to 3–5 cm (see Fig. 1, 2).

A number of studies show that narrow band imaging (NBI) endoscopy increases the detection rate of heterotopia by approximately 3 times compared with standard white light endoscopy (Fig. 7) [11, 16]. In a study by C. L. Cheng et al. [17], which included 99 patients with heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus, small foci of heterotopia were identified in 54% of subjects using a narrow spectrum versus 17% detected in white light. These results allow us to confidently recommend the use of virtual chromoendoscopy for diagnosing “inlet patch” [16].

S. Blanco et al. [15] proposed using the frequency of detection of heterotopic areas in the proximal esophagus as a criterion for the quality of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, similar to the adenoma detection rate (ADR) criterion for colonoscopy.

Clinical manifestations

Clinical manifestations in patients with esophageal heterotopia of the coolant are absent in most cases. The appearance of symptoms is due to laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) or complications associated with the “inlet patch” (perforations, strictures, fistulas, as well as neoplastic transformation).

The greatest difficulty for diagnosis is caused by patients with symptoms caused by LPR: dysphagia, odynophagia, regurgitation, hoarseness, discomfort in the throat, soreness, burning, chronic cough, sensation of a “lump” in the throat [18]. According to V. Chong et al. [8], clinical manifestations are present in 73.1% of patients with “inlet patch”; complaints of sore throat, hoarseness and heartburn dominate. In the works of JS Baudet et al. [19] and OK Poyrazoglu et al. [20] in the presence of GM heterotopia, dysphagia is more common in patients, according to U. Weickert et al. [21] - recurrent hoarseness, dysphagia and heartburn. In a large study by WL Neumann et al. [22], which included a retrospective analysis of 487,229 patients undergoing endoscopy, showed that dysphagia, odynophagia, respiratory symptoms, and lumpiness were the most common symptoms [22]. The literature has noted an association of heterotopia of the coolant in the upper parts of the esophagus with chronic otitis and sinusitis, and bronchial asthma [8]. T. Talih et al. [23] suggested that heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus could be the cause of retrosternal pain in the patient, simulating an attack of unstable angina, requiring coronary angiography. Most researchers indicate the need for further research to study the potential relationship of clinical symptoms with both the location and/or size of the inlet patch, and the morphological features of the heterotopic mucosa [8, 10, 24].

Heterotopia of the coolant and functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract

Currently, there is no clear position regarding the nature of the relationship between esophageal heterotopia of the coolant and functional gastrointestinal disorders, primarily functional dyspepsia and non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). It requires clarification to what extent the observed symptoms can be caused by the presence of an “inlet patch” or attributed to manifestations of functional disorders. However, in certain categories of patients, awareness of the presence of GM heterotopia may help reassure them and reduce the severity of symptoms.

Alteration of the heterotopic GM by HP colonizing it is considered as one of the possible pathogenetic mechanisms for the appearance of symptoms [10]. In addition, there is evidence of impaired esophageal motility in patients with inlet patch [13].

One of the most interesting symptoms is the sensation of a “coma” in the throat (globus sensation), which occurs in patients with inlet patch with a frequency of 1.6–23.1% and is more common in women [10]. Such patients can be treated for a long time by psychiatrists, since it is widely known that globus sensation is considered a psychogenic problem [25]. The sensation of a “lump” in the throat may occur due to increased pressure in the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) due to the irritating action of the “inlet patch” or due to a reflex contraction of the ES due to a respiratory protective mechanism, probably associated with reflux. In this case, the cause of the symptoms may be not only the production of acid by the “inlet patch” cells, but also the secretion of mucin [14]. This fact is confirmed by the presence of symptoms in patients with the cardiac type of heterotopic GM and the lack of effect of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in some patients. The significance of the symptoms of LPR is recognized by clinicians and has led to changes in the Rome IV criteria for functional gastrointestinal disorders. The differential diagnostic list of conditions accompanied by a sensation of “lump” in the throat includes an “inlet patch” [26].

Heterotopia of the gastric mucosa and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

The most serious issue is to study the relationship between heterotopia of the gastric mucosa and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. In a systematic review of the literature performed in 2022, M. Orosey et al. [27], a total of 43 cases of adenocarcinoma in the proximal esophagus, arising in the locus of gastric heterotopia, were described; the vast majority of patients were male. The average age of the patients was 63.6±11.3 years. Other authors also demonstrate a low frequency of neoplasia in the “inlet patch” - 0–1.56% [28]. Based on these data, in 2022, the British Society of Gastroenterology and the Association of Upper Gastrointestinal Surgery of Great Britain and Ireland concluded that the inlet patch does not require follow-up and routine biopsy [29]. Most studies show that the risk of malignant transformation of heterotopic gastric mucosa into the esophagus does not depend on age, race, body weight and alcohol consumption; smoking is significant (23.7 pack/years versus 16.3 pack/years, p = 0.006) [30 ]. In 2022, French researchers [31] reported that among patients with an identified mutation of the CDH1 gene, which is associated with a high risk of developing diffuse-type hereditary gastric cancer, an “inlet patch” was detected and morphologically verified in 50%. However, in this group of patients, not a single case of esophageal cancer due to “inlet patch” was recorded [31]. Following this publication, P. Leclercq et al. [24] suggested that an island of columnar cell epithelium in the upper third of the esophagus poses a potential risk for the development of adenocarcinoma in patients who are carriers of the CDH1 gene mutation, including those who have undergone prophylactic gastrectomy, which necessitates a targeted endoscopic examination with collection of histological material from the ectopic coolant in the proximal section of the esophagus [24].

Results and discussion

In the presence of clinical manifestations of GERD and/or radiological signs of hiatal hernia, we followed a two-stage tactic: antireflux surgery and then, after 2-3 months, RFA of metaplasia foci.

Antireflux interventions performed at the first stage make it possible to achieve conditions for suppressing acid production and stopping the reflux of duodenal contents into the esophagus [1, 2, 11]. In a number of patients, these interventions can reduce the size of lesions [12]. Performing RFA in the second stage is possible only after Toupet fundoplication at 270°, since this option allows the cardia to be straightened to the required volume during ablation.

In our observation during control endoscopy after 3 months, among 65 patients who underwent the first antireflux stage (58 patients with hiatal hernia and 7 patients with cardiac insufficiency), in 54 (83.1%) the endoscopic picture of the esophagus remained without significant changes, in 7 ( 10.7%) lesions decreased. Among 37 patients who, for various reasons, did not undergo the second endoscopic stage of treatment, 10 patients underwent a control examination. Of these, independent regression of metaplasia of the esophagus was observed in 4 within a period of 3 months to 1 year. Progression was not detected in any case.

We recommended performing RFA to all patients who had histologically confirmed both intestinal and gastric metaplasia of the esophagus. Endoscopic treatment of columnar cell metaplasia without dysplasia is not the method of choice in everyday practice [4, 5], but complete eradication of metaplastic epithelium is the only way to significantly reduce the likelihood of developing adenocarcinoma. An objective assessment of the risk of malignancy in each specific case is hampered by the mosaic nature of Barrett's esophagus, the low specificity of morphological markers of a high risk of dysplasia, and the absence in the arsenal of modern pharmacology of agents that effectively neutralize the damaging effect of duodenal contents on the esophageal epithelium [11].

We chose this method of endoscopic destruction of mucus as it is the safest and currently produces the fewest side effects [5, 9]. The effect extends to the level of the muscular plate of the esophagus, therefore RFA is characterized by the lowest incidence of esophageal strictures. In view of this, RFA allows you to work with large area lesions. According to a meta-analysis of 37 studies, including 9200 patients, after RFA the incidence of strictures was 5.6%, bleeding 1%, perforations 0.06% (after RFA in combination with endoscopic resection), and no fatal complications after RFA were recorded in the world [3, 10]. Stricture formation is a major concern in the treatment of patients with Barrett's esophagus. The frequency of their development is 9-15% after argon plasma coagulation, up to 30% after photodynamic therapy, 9-10% after cryodestruction [3].

After RFA, patients complained of minor pain in the epigastrium and behind the sternum, which did not require the use of analgesics and persisted for up to 7 days (88.2% of patients). In 4 patients with a long segment, severe pain and fever up to 38.0°C were noted within 1 day. One patient had symptoms of esophagospasm. These symptoms can be combined under the term “postablation syndrome.” We did not note any complications after RFA.

Dynamic observation was carried out according to the following scheme: control endoscopy after 3, 6 and 12 months. During control endoscopy 3 months after RFA, 97.5% showed complete regression of endoscopic signs of metaplasia of the esophagus - in 2 patients with a long circular segment, incomplete eradication of metaplasia foci was noted in 1 session. One of them underwent a second RFA session and achieved complete eradication. The second patient did not appear for the repeat session; 6 months later he underwent antireflux surgery in another institution, against the background of which, 6 months after the operation, the lesion decreased from C3M3 to C0M1. During the control endoscopy after 6 months, 79 (96.3%) patients did not have columnar cell metaplasia; 3 patients (including those described above) had a relapse; in 2 of them, RFA was repeated. One of these patients had not previously undergone an antireflux stage due to the absence of radiological signs of hiatal hernia; in the same patient, 6 months after the second RFA session, a focus of gastric ectopia was again noted, which regressed independently after the antireflux intervention performed at the second stage in another institution. The presented clinical data may serve as evidence of an increased risk of relapse of metaplasia in the presence of ongoing reflux, even in the absence of radiological signs of hiatal hernia.

Progression of the disease in the form of development of dysplasia during the observation period after the procedure was not recorded in any patient.

According to world literature, the frequency of eradication of metaplasia foci reaches 92-98% without relapse within 2.5 years and 92% without relapse within 5 years [3, 4, 5, 14]. To completely eliminate metaplastic epithelium, 1-2 procedures are usually required. The number of RFA sessions depends on the extent of the lesion and the conditions under which regeneration occurs: in conditions of persistent reflux, it takes longer. Relapses of metaplasia are caused by the formation of metaplastic epithelium again under conditions of reflux. Small areas of intestinal metaplasia may also remain hidden under the resulting squamous epithelium (the so-called hidden Barrett's esophagus). Predictors of relapse, according to F. Van Vilsteren et al. [13], are a pre-procedure peptic stricture of the esophagus or severe esophagitis, anamnestic data on the formation of newly columnar epithelium after ablation or resection, a long history of Barrett’s esophagus, the likelihood of relapse also depends on the length of the segment [14].

Treatment

A unified approach to the treatment of patients with esophageal heterotopia of the coolant has not been developed. Almost all authors are inclined to believe that asymptomatic gastric heterotopia of the esophagus does not require treatment [1]. If there are complaints, acid suppressive therapy with PPIs is indicated to relieve symptoms caused by acid secretion. The duration of PPI prescription is not clearly defined, but the tactics used in the treatment of GERD are considered justified: “step-down” or “step-up” therapy for 4–8 weeks, followed by PPI prescription on demand. If there are relapses despite a high dose of PPI, adding an H2 receptor antagonist in the evening may prevent nocturnal acid breakthrough. Interestingly, one study showed a decrease in the size of the heterotopia locus after a course of PPI [11].

The ineffectiveness of conservative measures is an indication for complete endoscopic or surgical removal of heterotopic foci, with endoscopic ablation methods being preferred.

In recent years, several publications have appeared on the use of radiofrequency ablation (RFA) to treat heterotopia of the coolant in the proximal esophagus [32]. In 2015, RH Cartabuke reported successful endoscopic mucosal resection of an area of high dysplasia in the “inlet patch” in combination with RFA of the entire heterotopic area, localized at a distance of 19 to 22 cm from the incisors and covering 75% of the circumference of the esophagus. Follow-up examination after 6 months. showed complete eradication of the heterotopia area [18].

A. Meining et al. [33] studied the effect of argon plasma coagulation (APC) (coagulation power was 60 W, argon flow rate was 2 l/min) on the relief of symptoms in 10 patients with the presence of heterotopic coolant and complaints of a feeling of “coma” in the throat and/or a sore throat. The authors noted a significant improvement in the well-being of patients, the almost complete disappearance of these symptoms after 8 weeks. after therapy [33]. In a prospective randomized study of patients with similar complaints, M. Bajbouj et al. [14] demonstrated that 82% of patients who underwent PCA had a significant reduction in throat discomfort, and 90% had endoscopically documented complete disappearance of heterotopic areas compared with the absence of such in patients in the control group [14]. At the next stage of the study, after 27 months. follow-up, APC was assessed as successful in 74% of patients [34]. In a meta-analysis of 6 studies on the use of PCA in symptomatic patients with heterotopia of the coolant in the upper third of the esophagus, a response to therapy was recorded in more than 80% of patients. The median follow-up time in these studies ranged from 1 month. up to 36 months [14].

In the presence of complications, such as strictures and fibrosis, a biopsy is indicated to exclude malignancy and dilatation. Y. Shimamura et al. [35] demonstrated a case of successful balloon dilation of a proximal esophageal stricture caused by the presence of a 3 cm circular “inlet patch” in a 67-year-old patient with dysphagia.

The presence of dysplasia and cancer at the heterotopia locus requires the implementation of algorithms accepted in oncology, which include a combination of surgery with chemoradiotherapy.

Endoscopic mucosal resection has been described in 1 case of high-grade dysplasia [18] and in 6 patients with early esophageal adenocarcinoma [36]. Two of these patients had no evidence of disease at 12 months. and 31 months observations accordingly.

Over the past decades, there have been significant changes in the incidence rates of adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Now in Western Europe and the USA, in most cases of esophageal cancer, adenocarcinoma is detected. In the United States, the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has increased by almost 300% over the past 30 years (Fig. 1)

[1, 2].

Figure 1. Incidence rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in the United States (1975–2000) [3].

In Russia, this trend (an increase in the incidence of adenocarcinoma and a decrease in the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma) is not so clearly visible: in 7-20% of cases of diagnosed esophageal cancer there are histological signs of adenocarcinoma. However, it is difficult to assess the reliability and accuracy of such data: the disease is detected in the late stages of advanced cancer, when it is impossible to determine where the tumor has formed - in the distal esophagus (DOE) or in the proximal stomach. Among all oncological pathologies of the digestive system, esophageal cancer and stomach cancer have the highest mortality rates. The prognosis after the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma is unfavorable: 5-year survival rate does not exceed 10-20%, and improvements in treatment methods make a less significant contribution to improving these indicators [4, 5].

Recently, our understanding of the causes of esophageal adenocarcinoma, the routes of spread and progression of the process, and the possibility of early detection of the tumor has significantly expanded. This allows us to optimistically consider the issues of organizing screening, detection and timely treatment of precancerous pathology. According to authoritative experts, adenocarcinoma of the digestive tract (AT) most often develops in pathologically altered mucous membranes. The chronic inflammatory process is considered as one of the important links in the chain of processes leading to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus [6, 7]. The main diseases against which cancer develops significantly more often have also been identified. For esophageal adenocarcinoma, the underlying disease in most cases is Barrett's esophagus (BE).

According to M.I. Davydov, since the first description made in 1950 by the English surgeon N. Barrett, the disease, known in gastroenterology and oncology as PVT, remains the most controversial and poorly understood pathology of PVT [8].

N. Barrett was convinced that the disease, the description of which he published, was a combination of a hiatal hernia (HH) with translocation of the proximal stomach into the mediastinum in the form of a tube (“tubulated stomach”) with shortening and ulceration of the distal third of the esophagus [9]. Only 3 years later, P. Allison and A. Johnstone showed that what N. Barrett described as a “tubulated stomach” was an esophagus with columnar cell metaplasia of the epithelium and the formation of peptic ulcers (“Barrett’s ulcers” - “Barrett ulcers”)[10 ]. Since that time, for many decades, the pathological process, characterized by columnar cell metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa and often accompanied by ulceration or stricture, was called BE. However, the most significant sign of “true” BE was considered to be the identification during a morphological study of goblet cells containing acidic mucin and stained with Alcian blue dye at pH 2.5. This evolution in the understanding of this pathology was determined, on the one hand, by the improvement of diagnostic methods, and on the other, by the lack of clear criteria for the effective definition of this pathology and reliable methods for identifying intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and early cancer. As a result of numerous studies conducted over the past 20 years, some criteria for PB have been transformed. It has been shown that the presence of foci of specialized intestinal epithelium with goblet cells in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia increases the risk of developing DOP adenocarcinoma, and it is this circumstance that determines the precancerous potential of BE. Based on this, intestinal metaplasia has become an important diagnostic criterion for patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [9]. For a long time, the following definition of BE was generally accepted in clinical practice: a pathological condition in which part of the squamous epithelium of the mucous membrane of the DOP is replaced by metaplastic columnar epithelium. A segment of columnar metaplasia should be identified by endoscopic examination, located above the esophagogastric junction or junction (Z-line) and confirmed morphologically by detecting specialized intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 2)

[11].

Figure 2. PB. a - endoscopic picture

Figure 2. PB.

b — histological picture: intestinal metaplasia of the DOP with goblet cells (Mowry-CHIC staining with alcian blue). However, intestinal metaplasia is not always the growth zone of esophageal adenocarcinoma, so in 2011 the American Gastroenterological Association proposed a more modern definition of BE: “BE is a segment of columnar metaplastic epithelium of the esophagus that has precancerous potential. Intestinal-type epithelium in the metaplasia segment has the greatest precancerous potential and requires diagnosis” [12]. From this definition it follows that two studies - endoscopic and morphological - form the basis for the correct diagnosis of this pathological condition. The timely diagnosis of BE, dysplastic changes in the mucous membrane and early forms of esophageal adenocarcinoma depends on the endoscopist, his knowledge, methodological skills, correct interpretation of identified changes in the mucous membrane, experience and, finally, technical equipment.

Prevalence of GERD and columnar cell metaplasia in DOP

BE is one of the most serious complications of GERD - a chronic relapsing disease caused by spontaneous, regularly recurring retrograde entry of gastric and/or duodenal contents into the esophagus, leading to damage to the esophagus and/or the appearance of characteristic symptoms (heartburn, retrosternal pain, dysphagia). As an independent nosological entity, GERD was officially recognized in the materials on the diagnosis and treatment of this disease, adopted in October 1997 at the interdisciplinary congress of gastroenterologists and endoscopists in Genval (Belgium) [13]. Studies conducted around the world and covering large populations show that symptoms of reflux disease are experienced by more than 1/3 of the population, and daily heartburn - by 7-10%. Complications of reflux disease and heartburn (the main symptom of GERD) are more often observed in representatives of the white (12.3 and 34.6%, respectively) and black (2.8 and 46.1%, respectively) races compared to residents of East Asia (up to 2. 6%) [14]. It is quite difficult to assess the prevalence of columnar cell metaplasia in the DOP, since more than 80% of patients remain undiagnosed, which is reflected in data from an American study of autopsy material [15]. A study conducted in the USA by the same group of specialists (A. Cameron et al.) found a 28-fold increase in the number of clinically diagnosed cases of metaplastic changes in the DOP for 1965-1995. Data from endoscopic examination of the upper sections of the esophagus in patients admitted to clinics with symptoms of dyspepsia or for colonoscopy indicate differences in the prevalence of columnar cell metaplasia of the esophagus depending on ethnic and geographical factors (table).

The prevalence of GERD in Russia among the adult population is about 40%, and 45-80% of them have esophagitis. In 10-35% of cases, this is severe esophagitis with multiple erosive lesions of the mucous membrane of the abdominal cavity. BE of varying degrees of extent is diagnosed on average in 8-15% of patients with esophagitis. Esophageal adenocarcinoma develops in 0.5% of patients with BE per year with low-grade dysplasia, and in 6% per year with high-grade epithelial dysplasia [22]. Risk factors for the development of BE include middle and old age, male gender: in most patients this pathology was diagnosed at 50-60 years old and in men - 3-4 times more often than in women.

Pathogenesis

One of the main reasons for the development of GERD and BE is gastroesophageal reflux - the reflux (entry) of gastric contents, and primarily hydrochloric acid, into the esophagus. With the development of such reflux, the pH in the DOP significantly shifts towards low values due to the ingress of acidic stomach contents. Prolonged contact of the esophageal mucosa with acid refluxate, which also contains pepsin, contributes to the development of its inflammation. Bile acids and enzymes, which can also be part of the refluxate, can have a strong damaging effect on the mucous membrane of the esophagus if the motility of the upper parts of the PVT is impaired. Esophagitis in some cases is accompanied by a structural restructuring of the epithelium of the esophageal mucosa with the formation of gastric or intestinal metaplasia, which is the background for the development of adenocarcinoma. Analysis of the results of numerous studies shows that the risk of developing cancer in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia is associated primarily with the presence of intestinal metaplasia (incomplete intestinal metaplasia, type II and III) [23, 24].

In the esophagus, metaplastic changes begin with the appearance of first the columnar epithelium of the gastric type, and then the epithelium of the colonic type. Exposure to acid in the esophagus increases, on the one hand, the activity of protein kinases that initiate the mitogenic activity of cells and, accordingly, their proliferation, and, on the other hand, inhibits apoptosis in the affected areas of the mucous membrane. In 50-80% of cases, dysplasia against the background of BE and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is characterized by mutations of genes involved in the regulation of the cell cycle, DNA repair and apoptosis [21]. The results of research in this area indicate the important role of the genes (proteins) P53 and P63 involved in the development of squamous epithelial cells. In the esophagus, P63 protein expression is detected only in squamous epithelial cells and is absent in columnar cell metaplasia. In the absence of P63, mucosal stem cells cannot begin differentiation along the path of squamous epithelial cells; as a result of this disorder, columnar epithelial cells are formed [25, 26]. The basis for the origin of intestinal-type epithelial cells can be both stratified squamous epithelium and cuboidal epithelium of the ducts of the glands of the submucosal layer of the esophagus [27], as well as cardiac-type epithelium in the esophagus exposed to refluxate [28]. Among the factors influencing the processes of carcinogenesis

in the area of the esophagogastric junction (EGJ), it is also necessary to take into account smoking, alcohol, increased body weight and bile reflux.

The results of dynamic observations of patients with BE indicate that the development of adenocarcinoma occurs through a multi-stage pathological process, which is characterized by an increase in the degree of dysplasia - the pathology preceding adenocarcinoma. An important promoter of this process is nitrite oxide, which can accumulate in pathologically altered DOP tissues and cause genetic changes that occur parallel to the transition from metaplasia to dysplasia and then to adenocarcinoma [29].

Diagnosis and screening of BE and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

Endoscopic examination is key in diagnosing BE. While other methods (radiography, scintigraphy) provide data only to suggest this diagnosis, the endoscopic method makes it possible to establish it with a high degree of probability. An endoscopic examination determines the extent of changes in the mucous membrane, the ratio of the zone of changes in the mucous membrane along the length to the proximal joint, as well as the proximal border in relation to the incisors. In this case, the spread of the metaplasia zone is clearly visualized in the form of foci of hyperemia (“tongues of flame”) against the background of the “pearly white” epithelium of the esophagus. One of the important tasks of endoscopic examination is obtaining biopsy material. The purpose of the morphological study is to confirm the presence of metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa, as well as to identify areas of dysplasia and foci of adenocarcinoma.

From an endoscopic perspective, accurate diagnosis of BE presents several challenges. One of them is to determine the key landmarks - the zone of the pancreas, the Z-line and the boundaries of the segment of columnar cell metaplasia. Another problem is the accuracy of biopsy in the focal distribution of areas of intestinal metaplasia and dysplasia in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the esophagus and the difficulties of endoscopic diagnosis of these foci [30].

Key guidelines for endoscopic diagnosis

PZhS zone

- This is the area of connection of the muscular layers of the esophagus and the cardiac part of the stomach.

It corresponds to the boundary between the tubular structure of the esophagus and the proximal part of the stomach with longitudinal folds. This anatomical boundary is defined in the area of the proximal edge of the longitudinal folds of the gastric mucosa (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Endoscopic picture of BE. The arrows indicate the proximal edge of the folds of the gastric mucosa, corresponding to the area of the pancreas. Another additional landmark of the PVC is the distal border of the longitudinal vessels of the mucous membrane visible during endoscopy (palisade or longitudinal intramucosal vessels). These vessels, first described in 1963 by Carvalho, are veins located in the mucosa above the lamina propria. In the stomach they are located in the submucosal layer and extend into the superficial layers of the mucous membrane only in the area of the border of the stomach and esophagus.

In the mucous layer of the esophagus, they run proximally for about 2 cm parallel to each other in the form of a “picket fence” and then plunge back into the submucosal layer, forming larger veins. The Japanese Society for the Study of Diseases of the Esophagus recommends defining the esophageal vein precisely along the distal edge of these longitudinal vessels [31] (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Longitudinal vessels of the mucous membrane of the DOP. Some of the vessels cross the border of squamous and columnar epithelium (Z-line) in the distal direction. The arrow shows the PVC zone.

Jagged line, or Z-line,

- the border between the pale pink stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus and the brighter and darker columnar epithelium of the stomach

(Fig. 4).

The letter “Z” stands for zero, the zero mark of the zone where the squamous epithelium of the esophagus ends [32].

Normally, this uneven line coincides with the anatomical border of the esophagus and stomach. In the presence of columnar cell metaplasia in the DOP, the Z-line does not coincide with the PJS zone.

In the case where the Z-line is located above the anatomical border of the esophagus and stomach (AGB), a segment of columnar cell metaplasia is determined, located between these two landmarks. Modern diagnosis of the boundaries and extent of the segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the DOP is based on the Prague criteria (The Barrett's Prague C&M Criteria), developed by The International Working Group for the Classification of Oesophagitis at the 12th European Gastroenterological Week (Prague, 2004). These criteria involve determining the proximal border of the circular segment of metaplasia, as well as the maximum extent and the uppermost border of the longest “tongue” of metaplasia extending from the circular segment to its upper edge (value “M”). The length of the circular segment of columnar cell metaplasia is measured from the edge of the gastric folds (GPL) to its proximal level (value “C”; Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Prague criteria for the diagnosis of BE [33]. The length of the circular segment of metaplasia is 6 cm, the maximum length is 14 cm; endoscopic conclusion: PB S - 6, M - 14. Small islands of metaplasia located proximal to the common segment, separate from it and not associated with it, are not taken into account.

The presence of an axial esophagogastric hernia in the patient significantly changes the position of the key landmarks for diagnosing BE. That is why the diagnosis of this pathological condition is also an important element of endoscopic examination and involves determining the narrowing corresponding to the POD, located distal to the PVC zone [34].

Diagnosis of intestinal epithelium in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia

Histological examination in the BE zone reveals three types of glandular epithelium: epithelium of the fundus of the stomach (integumentary pit), cardiac (or transitional type) and specialized (special) intestinal epithelium with goblet cells. The diagnosis of BE involves morphological confirmation of the presence of a specialized, intestinal-type epithelium in the distal segment of the esophagus. If histological examination reveals only cells of the fundic or cardiac type, one should not speak of BE, but only of columnar cell metaplasia of the esophagus, which is not associated with a high risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma. Endoscopic examination of the metaplastic segment of the esophagus with so-called blind biopsies at four points around the circumference of the esophagus and along each centimeter along the length of the segment was the “gold standard” for diagnosing BE. However, it has been shown that the accuracy of such diagnosis of intestinal metaplasia foci is 48.2% [35].

Is it possible to increase the efficiency of diagnosis and dynamic monitoring of patients with BE in order to timely detect not only specialized intestinal epithelium, but also dysplastic changes in the epithelium, as well as early cancer?

Currently, it is relevant to develop new and determine the effectiveness of existing methods for staining the mucous membrane of the DOP, which make it possible to effectively diagnose metaplastic, dysplastic changes, as well as early forms of cancer. In addition, there are a number of new optical endoscopic techniques that make it possible to avoid performing “blind” biopsies. Among these techniques, the most effective are chromoendoscopy, magnifying and narrow-spectrum endoscopy.

Chromoendoscopy

The methylene blue staining technique, based on the absorption of the dye by metaplastic intestinal epithelium, is effective in diagnosing foci of intestinal metaplasia in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the DOP. It is this technique that allows you to objectively assess the localization, size and distribution of foci of intestinal metaplasia (Fig. 6, a).

Figure 6. Chromoscopy.

a - foci of intestinal metaplasia after staining with 0.5% methylene blue solution look like blue spots against the background of pink gastric-type epithelium, which does not absorb the dye. The indigo carmine staining technique, which allows one to highlight and emphasize structural surface changes in the mucous membrane, helps in the diagnosis of focal lesions of the mucous membrane, including early cancer. Performing a targeted biopsy of areas stained with methylene blue followed by a morphological examination of gastrobiopsy specimens allows one to assess the type of intestinal metaplasia and timely diagnose foci of epithelial dysplasia occurring against the background of metaplasia and early forms of cancer. However, chromoscopy techniques are not highly specific for metaplastic and dysplastic changes in the epithelium of the DOP. Methylene blue dye can stain not only foci of intestinal metaplasia, but also be adsorbed in the area of erosions and ulcers, which leads to false-positive diagnostic results (Fig. 6, b).

Figure 6. Chromoscopy. b — false positive results of chromoscopy, methylene blue dye is adsorbed in the area of linear erosions and ulcers.

Magnifying endoscopy

Magnifying endoscopy allows you to study in detail the microarchitecture of the mucous membrane of a segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the esophagus using an optical 115-fold magnification of its surface, to determine the types of patterns corresponding to metaplastic and dysplastic changes in the epithelium. This technique, in combination with 0.5% methylene blue chromoscopy, showed high specificity and sensitivity not only in diagnosing foci of intestinal metaplasia, but also dysplastic changes in the epithelium in patients with BE, and made it possible to determine the types of microstructure of the surface of the mucous membrane (Fig. 7),

Figure 7. Magnifying endoscopy (115x optical magnification) of a segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the DOP. The type of pattern of “longitudinal ridges” corresponds to the intestinal epithelium (IE). corresponding to these pathological changes [36].

Narrow band endoscopy

Narrow-spectrum endoscopy is one of the most modern endoscopic techniques registered by the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation and approved for use in Russia. Endoscopic examination with narrow-spectrum imaging function (narrow band imaging) is based on the use of special narrow-spectrum optical filters that change the spectrum of the light flux. The depth of penetration of the light flux depends on the wavelength: light waves of a longer spectrum (for example, red) penetrate deeper into the tissue, while the visible blue spectrum (shorter waves) is able to penetrate only the superficial layers of tissue, which allows them to be examined in more detail microstructure. Thus, the use of special narrow-spectrum filters in this system, transmitting light fluxes with a wavelength of 415 and 445 nm and delaying light waves that penetrate deeper into the tissue, allows for improved visualization of the surface of the mucous membrane. In addition, narrow-spectrum light waves are well absorbed by tissue hemoglobin, which makes it possible to study the microvascular pattern of the capillaries of the mucous membrane and submucosal layer of the esophagus. Using this technique, it is possible not only to increase the efficiency of determining key landmarks for the diagnosis of BE (longitudinal vessels), but also to identify the smallest disturbances in the architectonics of the epithelium, characteristic of metaplastic and dysplastic changes, as well as initial forms of cancer (Fig. 8).

Figure 8. Narrow band endoscopy. a - PB: diagnostics in the normal light spectrum

Figure 8. Narrow band endoscopy. b — narrow-spectrum endoscopy with optical image magnification: clearer visualization of the segment of metaplasia of the DOP with a violation of microarchitecture and vascular pattern, areas of intestinal epithelium and dysplasia (arrow).

Screening

The risk of developing adenocarcinoma against the background of BE is significant in patients with high-grade epithelial dysplasia in the area of the columnar cell metaplasia segment (Fig. 9).

Figure 9. Risk of developing cancer in patients with BE without dysplasia and with mucosal epithelial dysplasia of varying severity [37, 38].

However, the appearance of adenocarcinoma is preceded by the gradual progressive development of dysplastic changes with the loss of signs of differentiation by cells. Progression from mild (low grade) to severe (high grade) dysplasia on average can occur within

29 months, while the subsequent development of adenocarcinoma takes 2 times less time - 14 months [7]. The widespread prevalence of GERD and the identification of the cascade of precancerous events are potentially attractive targets for screening for BE and esophageal adenocarcinoma. One of the latest American recommendations (American College of Gastroenterology) suggests that endoscopic examination of the upper parts of the PVT is necessary for all patients with symptoms of chronic GERD due to the high risk of developing BE [39].

Endoscopic examination is the “gold standard” in the diagnosis of pathological processes in the mucous membrane of the esophagus, as it allows not only to visually determine the presence of columnar epithelium in the esophagus, but also to perform a biopsy for morphological confirmation of the diagnosis, diagnosis of dysplasia and early cancer. This allows us to consider the endoscopic method the most realistic tool for screening BE and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Using magnifying and narrow-spectrum endoscopy, we conducted a study of the pattern of different sections of the mucous membrane in the segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the esophagus, which made it possible to identify 5 types of epithelial pattern that do not have signs of dysplasia, as well as structural changes corresponding to dysplasia and early esophageal cancer (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. Types of epithelial patterns in the distal esophagus. a — DOP without neoplastic changes: oval pattern of pits (epithelium of the cardia of the stomach in the DOP)

Figure 10. Types of epithelial patterns in the distal esophagus. b - large and elongated oval pattern (oval ridges) characterizes intestinal metaplasia

Figure 10. Types of epithelial patterns in the distal esophagus. c - pattern of longitudinal ridges (intestinal metaplasia)

Figure 10. Types of epithelial patterns in the distal esophagus. d - pathological vessels and destroyed type of epithelial surface pattern (high-grade dysplasia). The results obtained and the correlation of endoscopic findings with histological examination data showed high specificity and sensitivity of the methods in diagnosing types of epithelium of the DOP [40]. This allows us to talk about a new direction in endoscopic screening of BE - “optical biopsy” and timely, highly effective detection of precancerous changes and early forms of cancer [41].

Treatment of patients with BE

Most patients with BE have symptoms caused by reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and characteristic of GERD - heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain, and sometimes extraesophageal manifestations (laryngitis, chronic cough, bronchial asthma). Treatment of patients with BE has two main directions: 1) treatment of symptoms and manifestations of GERD; 2) reducing the risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Modern principles of effective therapy for any form of GERD, and in particular erosive esophagitis, are reflected in the recommendations of the Russian Gastroenterological Association and consist of two main stages: induction of remission and maintenance of remission of erosive esophagitis. The first stage of treatment involves the administration of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in standard dosages for 4 weeks for single erosions and for 8 weeks for multiple erosive lesions of the mucous membrane. Maintenance therapy involves taking PPIs at half the dosage for 26-52 weeks. PPIs create optimal pH conditions for healing erosions and reducing hyperproliferation in metaplastic epithelium. This tactic makes it possible to achieve rapid improvement in clinical manifestations, positive dynamics of inflammatory changes determined by endoscopy, and reduce the time and costs of the treatment course. PPIs are the basis of both course and maintenance therapy for all forms of GERD, and in terms of total clinical effectiveness they are 2 times superior to histamine H2 receptor blockers, and prokinetics are 3 times superior [42]. After long-term use of drugs of this group, patients with BE experience a decrease in proliferation markers. And although it is believed that BE, as a rule, does not undergo reverse development, in some cases it is possible to achieve partial regression of a limited area of intestinal metaplasia [43]. In one of the few randomized studies, in which 68 patients with BE received 40 mg of omeprazole (group 1) and 150 mg of ranitidine (group 2) twice a day for 24 months, a small but statistically significant regression of the segment was established metaplasia. A decrease in segment length and area by 8% was recorded only in group 1 of patients (those receiving omeprazole). No changes were noted when taking ranitidine [44].

Preventing the progression of metaplastic changes and neoplasia in patients with BE remains a complex and poorly understood problem. Two studies showed that in 230 and 80 patients with GERD who received long-term therapy with omeprazole in different daily doses (from 20 to 80 mg), during follow-up (an average of 6.9 years) in 12.0 and 14 5% of cases, respectively, revealed metaplastic changes in the DOP, characteristic of BE [45, 46]. In another study of 350 patients with BE, the risk of developing dysplastic changes (for at least 2 years) was 5.6 times higher than in those not receiving regular PPI therapy over an average follow-up period of 4.7 years [47 ]. The results of work in this area generally indicate that PPI therapy cannot in all cases prevent the development of metaplastic and dysplastic changes in the DOP in patients with GERD. Further research is needed in this area, improving the mechanisms for recording the smallest structural changes in the mucous membrane, which is possible using new optical endoscopic techniques.

If drug therapy is ineffective, as well as dysplastic changes in the mucous membrane are detected, surgical and endoscopic treatment methods can be used. A retrospective analysis of the results of surgical operations (fundoplications) did not reveal any significant advantages of this technique compared to drug therapy with PPIs. Fundoplication does not prevent the occurrence of BE in patients with GERD, nor its progression to esophageal adenocarcinoma [48]. Endoscopic techniques for radiofrequency ablation and resection of metaplastic and dysplastic changes in patients with BE are an alternative to surgical resection, which has a high risk of complications (Fig. 11)

[49, 50].

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. a - early cancer in the proximal part of the belly button (indicated by arrows)

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. b — result of endoscopic tumor resection: large ulcerative defect in the area of the performed operation

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. c — macroscopic specimen: resected early cancer and the area of the metaplasia segment are fixed with needles on a special board and prepared for histological examination

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. d — histological specimen: adenocarcinoma (early cancer) in the PB area pT1 m2 V0 L0 G2 R0

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. e — radiofrequency ablation of the entire segment of the benign tumor as the second stage of treatment (4 months after resection of early cancer)

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer. f — treatment result: the entire segment of columnar cell metaplasia of the DOP was subjected to ablation

Figure 11. Treatment results for a patient with early esophageal cancer.

g — epithelization of the ulcerative defect in the area of resection of early cancer 2 months after ablation and long-term PPI therapy: squamous epithelium in the area of resection and the BE segment. Endoscopic treatment should be accompanied by adequate antisecretory PPI therapy to ensure effective healing of mucosal defects in the area of distant foci of metaplasia or dysplasia and to create conditions for the appearance of stratified squamous epithelium of the esophagus in these areas. Despite the high efficiency and relative safety of argon plasma and electrocoagulation, as well as laser destruction, these ablation techniques do not always lead to histological eradication of intestinal metaplasia and cannot prevent the development of dysplastic changes in 100% of cases [51]. The current strategy and algorithm for managing patients with BE are presented in Fig. 12.

Figure 12. Algorithm for the management of patients with BE [53]. This algorithm of the doctor’s actions involves, firstly, diagnosing BE in accordance with the Prague criteria, and secondly, mandatory biopsies of all visible pathological areas and epithelium in the area of the metaplasia segment, as well as the use of new optical endoscopic technologies for diagnosing dysplastic changes and early esophageal cancer. Endoscopic monitoring of patients without dysplasia is subsequently carried out every 3 years. When dysplasia and early cancer are detected, the diagnosis must be established by at least two morphologists. If adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia is detected, endoscopic surgery is recommended (if indicated and possible), followed by staging of the process and determination of treatment tactics. In the case of low-grade dysplasia, it is possible to perform radiofrequency ablation followed by dynamic observation in an expert center [52].

The aggressive course of esophageal tumors and unsatisfactory treatment results dictate the need to search and study new possibilities for preventing the development of the tumor process, effective endoscopic diagnosis of pretumor pathology, and the choice of