General information

Diseases of the digestive system in children occupy second place (after diseases of the respiratory system).

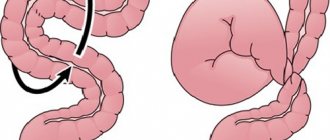

Taking into account the anatomical and physiological characteristics of the child, dysfunction of the stomach and intestines occurs in almost all children at an early age and is functional. This condition is associated with adaptation and maturation of the gastrointestinal tract in infants. From the upper part of the digestive tract in children, spasm of the pyloric part of the stomach often occurs. The pyloric region is the border between the stomach and the duodenum, and the pyloric opening communicates the stomach with the duodenum. The sphincter of the pyloric opening (called the pylorus) is a developed muscular layer. The sphincter opens after food enters the stomach, and peristaltic waves move the food bolus into the duodenum. Its closure occurs after food enters the duodenum.

Violation of sphincter tone in the form of increased tone and spasm causes difficulty in the evacuation of food from the stomach. Pylorospasm in infants is a functional disorder and is associated with a violation of autonomic innervation and the characteristics of the autonomic nervous system in a given child.

Muscles react with spasms to various external influences - stress, excess food, vitamin , nicotine . Functional disorders imply the presence of symptoms in the absence of organic changes. The risk group for the formation of functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract in infancy consists of premature children, functionally immature children, those who have suffered birth trauma and intrauterine hypoxia . This condition goes away on its own by 5-6 months due to the improvement of the autonomic nervous system and gastrointestinal tract. Pyloric spasm, which depends only on the influence of the nervous system, must be distinguished from pyloric stenosis .

Pyloric stenosis or hypertrophic pyloric stenosis is a disease of the gastrointestinal tract associated with hypertrophy (thickening) of muscle tissue in the pylorus area and abnormal arrangement of muscle fibers, as well as excessive development of connective tissue. Degeneration of the muscle layer develops against the background of disturbances in neuroregulatory influences. This condition does not go away on its own and requires surgical intervention.

In children, congenital pyloric stenosis occurs, which is a developmental defect and in 15% of cases is a hereditary pathology, since the family nature of the disease has been established. In addition, there is a relationship between the incidence of the disease and parental consanguinity.

Proof that pyloric stenosis is a developmental defect is its combination with other defects - esophageal atresia , diaphragmatic hernia . Pyloric stenosis often occurs in Alper syndrome (a degenerative disease of the cerebral cortex). The critical period of this defect corresponds to the beginning of the 2nd month of embryonic life.

Pyloric stenosis most often appears in the first weeks of a baby’s life, sometimes later. This depends on the degree of narrowing and compensatory abilities of the gastrointestinal tract. The relevance of early diagnosis of the disease is due to the risk of developing complications - water-salt imbalance, malnutrition , sepsis , aspiration pneumonia , osteomyelitis , which are the cause of death in children.

Signs of esophageal stenosis

There are several signs by which esophageal stenosis can be diagnosed, these traditionally include the following:

- unpleasant pain when eating, and the pain is felt as the food moves in the esophagus;

- salivation is constantly observed;

- one feels nauseated, often vomiting and belching.

There are several degrees of damage to esophageal stenosis:

- First degree. Problems arise from time to time when swallowing solid foods. In general, the condition is satisfactory.

- Second degree. Food can pass through the esophagus only in semi-liquid form.

- Third degree. Only liquid food can pass through the esophagus.

- Fourth degree. It is very difficult to swallow even saliva and water.

Pathogenesis

From a pathogenetic point of view, it is associated with hypertrophy of the circular muscles of the pylorus and partial muscle hyperplasia. In the prenatal period, partial excessive growth of the stomach anlage occurs from the mesenchyme in the pyloric region, from which the muscle elements differentiate. However, hypertrophy of the muscle layer develops postnatally. The anterior and upper walls of the exit section are the most thickened, as a result of which the pylorus takes on the shape of a spindle. From the beginning, the child does not experience inflammation or swelling of the pyloric mucosa. The addition of mucosal edema to the existing hypertrophy and hyperplasia of the pyloric muscles is manifested by increasing obstruction of the pyloric region.

Many believe that a spastic component is added (that is, spasm is secondary); some authors argue that spasm and hypertrophy appear simultaneously. Among the causes of spasm and hypertrophy are the immaturity of the autonomic regulation of gastric function. The visceral organ is under the control of regulatory influences. The pathogenesis of spasm is due to disruption of interactions between the diseased organ and regulatory systems. From the side of the narrowed pylorus, signals enter the cerebral cortex, and in response, return impulses go to the pylorus. The cerebral cortex constantly receives signals that disrupt its regulatory function. A vicious circle is created: impulses from the center disrupt the function of the gatekeeper, and impulses from it to the center deepen the damage to the regulatory system. Breaking the chain restores normal relationships.

Pylorospasm is associated with increased tone of the sympathetic nervous system. The resulting prolonged spasm of the pylorus muscles makes it difficult to empty the stomach. Hypertonicity can be caused by fetal hypoxia , posthypoxic encephalopathy , increased intracranial pressure and hydrocephalic syndrome .

Causes

To date, the reasons why stenosis of the stomach (its pyloric section) occurs are not known. There are various theories:

- Spasmogenic, according to which spasm occurs primarily, against the background of which hypertrophy .

- Dualistic - spasm and hypertrophy develop simultaneously.

- Neurogenic.

- Psychogenic. There is evidence that pyloric stenosis is more common in children whose mothers were in a state of nervous stress in the third trimester.

- Hereditary.

- Hormonal.

erythromycin and azithromycin has not been fully confirmed .

However, it has been proven that this condition is associated with factors:

- male gender (5 times more common in boys);

- smoking during pregnancy;

- lack of folic acid and B vitamins during pregnancy;

- premature birth;

- various congenital defects;

- delivery using cesarean section;

- low weight of the newborn;

- artificial feeding in the first months; at the same time, the risk of developing pyloric stenosis increases 4.5 times.

This is because formula contains a higher concentration of casein proteins compared to breast milk and does not contain enzymes that facilitate the digestion of proteins. All these factors complicate the digestion process in infants.

Changes in the pylorus always begin with pylorospasm . In older children and adolescents, the causes of this functional state are as follows:

- gastritis with high acidity with frequent exacerbations;

- peptic ulcer (stomach and duodenum);

- chronic intestinal diseases;

- dysbacteriosis;

- deficiency of B vitamins;

- biliary dyskinesia;

- physical overload;

- stress;

- hysterical neurosis .

Secondary (acquired) pylorospasm in adults can be caused by:

- organic pathology of the gastrointestinal tract (for example, peptic ulcer , chronic antral gastritis , cholecystitis , hiatal hernia, cholelithiasis , hyperacid gastritis );

- cicatricial changes after a chemical burn.

Also in adults, primary (neurogenic) pylorospasm is noted, the cause of which is:

- neuroses;

- hysteria;

- zinc and lead intoxication;

- mental stress;

- emotionally stressful situations;

- addiction.

If we talk about the factors that provoke pylorospasm in adults, then it is worth noting nutritional disorders: overeating, irregular meals, changes in diet, excessive consumption of coarse fiber and carbohydrates. Food allergies and various exogenous factors are also important: vibration, ionizing radiation, taking medications (NSAIDs, glucocorticoids), high ambient temperature, smoking and occupational intoxications.

Pylorospasm and pyloric stenosis are links in the same chain of pyloric motility disorders: first, pyloric spasm occurs, which leads to muscle hypertrophy and pyloric stenosis.

Diagnostics

Primary diagnosis includes:

- survey of the baby's parents;

- examination of the child, palpation of the anterior wall of the abdominal cavity;

- examination of the skin, control of weight, level of development of the child, according to normal indicators.

The basis for making a diagnosis is a laboratory and instrumental examination of the baby:

Symptoms of pylorospasm in adults

- urine and blood analysis;

- Ultrasound - allows you to determine the size of the pylorus, changes in the thickness of its walls;

- FEGDS - examination of the stomach, esophagus and duodenum with an endoscope;

- radiography - used in rare cases, when previous research methods are ineffective.

Such a diagnosis allows you to confirm the diagnosis and distinguish pyloric stenosis from diseases with similar symptoms, especially from pyloric spasm, intestinal obstruction, and hiatal hernia.

Symptoms

Regurgitation and vomiting are characteristic symptoms of pyloric spasm and pyloric stenosis, but their severity and frequency in these conditions are different. With pylorospasm, the frequency and volume are inconsistent, and may even be completely absent on some days. Vomiting appears from birth. There are no pathological impurities in the vomit, and the amount of vomit is less than the amount of milk received. Signs of dehydration are absent or mild, children gain weight, but not enough for their age. The child's stool is daily and is not changed. The child is characterized by anxiety, he is noisy and there is sleep disturbance. When examining the abdomen, visible peristalsis of the stomach is not detected and pathological formations and pain in the epigastrium are not detected.

Symptoms of pylorospasm in newborns are more pronounced. At the end of the second or third week from birth, “fountain” vomiting appears, which is the main symptom of this disease. It occurs between feedings - first 15 minutes after it, and later this interval lengthens. This is due to the fact that the baby's stomach gradually expands. Vomiting at first is periodic, and later occurs after each feeding. The amount of vomit is greater than the volume received by the child in one feeding.

The vomit consists of curdled milk and does not contain bile. It is extremely rare for vomit to contain streaks of blood (an admixture of blood from injured small vessels or mucous membranes). Due to constant vomiting, the child remains hungry, restless and has an increased appetite for the next feeding.

In 90-95% of cases, infants develop a tendency to constipation , which is associated with insufficient food intake into the intestines (false constipation). The stool is dark green in color due to bile that continues to flow into the intestines. As a result of dehydration, children decrease the amount of urine they produce and the number of times they urinate. In this case, the urine becomes concentrated and dark yellow.

Due to persistent vomiting, exhaustion and dehydration develop, so the symptoms of pyloric stenosis necessarily include weight loss. The baby's weight turns out to be less than at birth. In children with persistent vomiting, not only is there a lag in physical development, but also iron deficiency anemia is detected, and blood thickening occurs. Due to the loss of potassium and chlorine through vomit and water, electrolyte disturbances develop.

When examining the abdomen, its bloating and increased gastric peristalsis, which resembles an “hourglass,” are often detected. Parents describe this symptom as follows: “waves running through the stomach.” The presence of gastric peristalsis is the most important symptom of pyloric narrowing. Peristaltic waves can be induced by stroking the stomach area or by giving the child water. The baby reacts to peristalsis by crying and sometimes vomiting. When palpating the abdomen between the navel and the xiphoid process on the right, a compacted pyloric part of the stomach in the shape of a plum is determined.

Symptoms of pylorospasm in adults in most cases include cramping epigastric pain. Patients experience a feeling of heaviness and pain in the stomach, possible slight weight loss, nausea, periodic vomiting and attacks of intense pain in the epigastric region in the form of colic. At the height of pain during a prolonged attack, the amount of urine excreted decreases. a urinary crisis occurs - light urine is released in large quantities.

Causes of development of esophageal stenosis

The cause of this disease is a developmental defect in the prenatal state. This pathology can be noticed already from the first days of a newborn’s life. The baby spits up milk quite persistently. If the stenosis is small, then it may not be noticed during the breastfeeding stage, but when solid food begins to be introduced, it makes itself felt.

If the stenosis is acquired, it is also characterized by a narrowing of the lumen. Obstruction of the esophagus is associated with one of the following reasons:

- the presence of scars that appear as a result of diseases such as peptic ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease, infectious and inflammatory lesions of the stomach;

- traumatic lesions of the esophagus, burns;

- neoplasms of the esophagus or adjacent tissues;

- enlarged lymph nodes, aortic aneurysm, abnormal arrangement of blood vessels.

Tests and diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in newborns

Diagnosis of pyloric stenosis in newborns and infants includes:

- Characteristic complaints of parents and medical history.

- X-ray examination. It is carried out in two stages. The first stage is a survey X-ray of the abdominal organs, performed with the child in an upright position. The stomach is found distended with air and contents. Its bottom is located below the navel and even at the level of the pelvic bones. There is less gas in the intestines than usual. Decisive in diagnosis is X-ray contrast examination, which is carried out at the second stage after plain radiography. Barium x-ray is useful only to rule out or confirm pyloric stenosis if there is any doubt. barium suspension with glucose solution or milk (50-60 ml of milk + 2 teaspoons of barium suspension) is used as a contrast agent The contrast agent is injected into the stomach through a thin catheter. After the contrast is administered, a series of images are taken after 20 minutes and 3 hours, if necessary - after 6 hours and 24 hours. The child should be in an upright position during the examination. If after 3 hours there is more than half of the contrast agent in the stomach, this is the main radiological criterion for pyloric stenosis. With pyloric stenosis, barium remains in the stomach for more than 24 hours without vomiting during this time. The second radiological sign of pyloric stenosis is “segmented” peristalsis of the stomach. On a lateral X-ray, the narrowed pyloric canal appears beak-shaped—a symptom of “antral beak.” X-ray examination is used to select one or another tactic of surgical intervention. Pylorospasm is also diagnosed x-ray - in this case, the pyloric patency is not impaired, but the stomach empties from the contrast after 3-6 hours.

- Ultrasonography. Reveals symptoms characteristic of pyloric stenosis: elongation of the pylorus (it has a length of more than 20 mm), thickening of the muscle layer (more than 4 mm) and narrowing of the lumen of the canal.

- Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is used to a limited extent at such an early age - only to clarify the diagnosis. The endoscopic method should be used as a final examination after radiography and ultrasound. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy reveals an overstretched stomach with pronounced folding of the mucous membrane in the antrum. Stenosis of the pyloric canal of varying severity is noted; the pyloric canal does not open when inflated with air. There is also no possibility of penetration into the duodenum even after the administration of atropine .

Procedures and operations

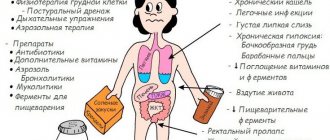

For pylorospasm, children and adults may be prescribed physical treatment:

- electrophoresis of papaverine hydrochloride ;

- electrophoresis of drotaverine on the epigastric region;

- paraffin applications.

A radical method of treatment is the Frede-Weber-Ramstedt operation, which restores the patency of the pyloric part of the stomach. The operation can be performed in several ways:

- Open access.

- Laparoscopic. The use of this technique during surgery allows you to restore patency and facilitate the postoperative period. This type of surgery is well tolerated in infancy.

- Transumbilical. Access to the surgical field through the navel. The newborn’s navel has elastic tissue and allows for “single laparoscopic access” operations - a laparoscope and two laparoscopic instruments can be inserted through one incision.

During the operation, an extramucosal dissection of the muscular layer of the pylorus is performed. Dissection of the serous-muscular layer removes the mechanical obstacle that narrows its lumen, and at the same time relieves spasm. Currently, this operation is most often performed laparoscopically.

On the day of surgery, one feeding is prescribed at 6 am. With pyloric stenosis, postoperative care and adequate feeding of the baby are important. After the operation, the child is placed in an elevated position of the head end, and feeding begins after 3 hours. Some authors recommend starting it after 6-8 hours, and before that, giving the child 5 ml of 5% glucose or Ringer's solution every 2 hours.

Before the first feeding (two after the operation), if the child shows anxiety, give him 2-3 teaspoons of saline or glucose solution and make sure that feeding does not cause vomiting. Portions of expressed milk are minimal at first - 10-20 ml every 2 hours, and the volume gradually increases. In general, there are 10 feedings per day with a night break.

In subsequent days, 10 ml is added to each feeding, that is, per day the amount of milk increases by 100 ml every day. At this time, the child receives expressed milk to control the amount and monitor the digestion process. After 4 days, breastfeeding is allowed for the first time - once or twice a day for 5 minutes. Then feeding continues with expressed milk. So, the amount of breast milk is gradually increased, and from the 7-10th day the baby is completely transferred to breastfeeding in an amount appropriate for his age. After the operation, vomiting sometimes persists once or twice a day, but after a day or two it stops.

Treatment

The main treatment method for pyloric stenosis in children is surgery. The doctor decides when to perform it, but usually the operation is not delayed. In addition to it, medications and diet may be prescribed, especially when it comes to older children who feed on their own.

Pyloric stenosis is strictly prohibited from being treated with folk remedies and herbs. Dehydration and other symptoms develop rapidly, and doctors warn parents against wasting time on ineffective treatments.

Preparation and performance of the operation

To save the child from developing complications, it is necessary to perform an operation. There are several options for surgical intervention; in recent years, doctors have been practicing the Frede-Ramsted method. The muscular layer of the pylorus of the stomach is dissected, affecting the serous layer, resulting in an increase in the lumen between this section and the duodenum.

It is important to make the incision along the avascular line of the rough edge of the pylorus, so as not to touch the mucous membrane

To perform an operation using this or another method, preparation is prescribed. Its main principles are the following rules:

- restoration of water balance, elimination of the consequences of dehydration by intravenous administration of saline;

- oral rehydration;

- gastric lavage – if necessary (for certain types of surgery);

- Antibacterial therapy – if necessary.

At the end of the operation, the peritoneum is sutured with interrupted sutures; with the correct work of surgeons over the years, a small seam remains in this place.

Postoperative period

In the period after the operation, it is necessary to monitor the baby’s nutrition; it is necessary that he and his mother spend some time in the hospital under the supervision of specialists.

Doctors usually give the following recommendations:

- a few hours after completion of the operation, administer glucose (5%);

- after 3-4 hours, feed the baby with expressed milk;

- on the first day, a single volume of milk per feeding should not exceed 30 ml;

- from the second day it is increased to 50 ml;

- You can put the baby to the breast no earlier than 5-6 days after the operation.

At first, you can put your baby to your breast a little slower. If vomiting occurs, it is better to wait with such feeding, giving milk in a bottle or formula for several days (as recommended by a doctor). Then you can try breastfeeding again.

Pyloric stenosis is a dangerous pathology, but if the symptoms are detected in time and surgery is performed, following all the doctor’s recommendations, only a small scar on the abdomen will remind you of the disease. An instrumental examination can confirm the diagnosis, and a gastroenterologist prescribes therapy.

Pyloric stenosis in children

Excessive growth of the muscular layer of the pylorus in the prenatal period leads to the fact that the pyloric region sharply thickens, acquiring a cartilaginous density. In this case, the mucous membrane gathers into longitudinal folds and sharply narrows the lumen. Pyloric stenosis in newborn boys occurs in 87%. The time of onset of symptoms depends on the degree of narrowing of the pylorus.

The most characteristic is the gradual onset of the disease with increasing symptoms. The general condition of the child at the onset of the disease does not suffer. At first, the baby receives little food, so the contraction is overcome by the muscular strength of the stomach. Parents do not see a doctor until 3-4 weeks. With an increase in the amount of food, the addition of a secondary spasm and a weakening of the stomach’s strength to push food, signs of illness appear - regurgitation and vomiting. Secondary spasm during stenosis contributes to the fact that the clinical picture appears more clearly.

Fountain vomiting becomes a constant symptom and appears after each feeding.

In 72% of children, its appearance occurs in the 2-4th week of life, and in 7% - in the first week. When studying the anamnesis, it becomes clear that all children initially experienced persistent regurgitation in the first days after birth and periodic vomiting. Over time, the frequency of vomiting per day reaches 4-5 times (less than the number of feedings). Prolonged vomiting leads to weight loss and the development of malnutrition . An indicator of the severity of the disease is daily weight loss - it is expressed as a percentage of birth weight. In severe cases of the disease, water-electrolyte metabolism is disrupted and metabolic alkalosis . The appearance of the child changes - sharp exhaustion, pale wrinkled skin and an “aged” face with wrinkles are striking. The child is restless and has an “angry” face.

Unlike pyloric spasm, when there is intermittent obstruction of the pylorus, which can be eliminated with conservative treatment, with pyloric stenosis the narrowing of the pylorus is permanent and can only be eliminated surgically.

Complications

Due to impaired contraction of the pyloric muscles, the stomach becomes stretched. Food that has entered it, but cannot descend into the duodenum, must go somewhere, so as the symptoms progress, severe vomiting begins and dehydration begins. Remains of food in the stomach that have not returned to the esophagus begin to rot and ferment. All this leads to complications such as:

- damage to the pylorus by an ulcer;

- gastrointestinal bleeding;

- anemia;

- baby's growth retardation;

- pancreatitis.

In severe, advanced cases, due to acute intoxication and dehydration of the body, there is a risk of death.

Children with advanced pyloric stenosis do not grow normally, their weight is critically low, and their internal organs are delayed in development

ATTENTION! If you do not promptly treat pyloric stenosis in newborns, not only the physical, but also the mental development of the baby will suffer - he is constantly in a stressful, restless state.

Diet

Diet table No. 1

- Efficacy: therapeutic effect after 3 weeks

- Terms: 2 months or more

- Cost of products: 1500 - 1600 rubles. in Week

The nutrition of children was discussed above; for adults with pylorospasm, mechanically and chemically gentle nutrition is recommended. Food should be taken warm. Avoid hot and cold foods rich in fiber. It is not advisable to consume spicy foods and seasonings, coffee, carbonated drinks, which can intensify the spasm. Table No. 1 meets all requirements .

Prevention

Prevention of the disease has not been developed, but taking into account risk factors, it can be assumed that the following general measures will be effective:

- A rational and balanced diet for a pregnant woman, including folic acid , vitamins and microelements.

- Minimizing stressful situations and psycho-emotional stress during pregnancy.

- Compliance with the work and rest schedule of a pregnant woman.

- Observation at the antenatal clinic to identify pregnancy pathologies.

- Normalization of the child's feeding regimen in order to eliminate overfeeding and regurgitation.

- Creating a prosperous environment for the child.

- For adults with pylorospasm, it is important to eliminate psycho-emotional stress and stress, and establish adequate sleep and rest.

Forecast

Pylorospasm with age, as the nervous system improves, regurgitation is reduced, vomiting disappears by 5-6 months. Vomiting in some children may resume with a fever, a cold, or after a conflict situation.

Pyloric stenosis can be treated with surgery. Pyloromyotomy shows good long-term results: children develop well, and X-ray control indicates normal gastric function and good emptying. There are no relapses after the operation. Mortality with proper surgical treatment is minimal - it is observed only among patients who are operated on late and their death is associated with exhaustion and its attendant complications.

List of sources

- Nagornaya N.V., Limarenko M.P., Bordyugova E.V. Rational therapy of functional gastrointestinal disorders in young children. News of medicine and pharmacy. 2008. 16(255) - pp. 14-15.

- Khavkin A.I. Functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract in young children. M., 2000. 71 p.

- Zaprudnov A. M. Handbook of pediatric gastroenterology. M., 1995. pp. 25–26.

- Botvinyev O.K. Turina I.E. Barmaver S.Z. Difficulties in diagnosing congenital pyloric stenosis in children. Russian pediatric journal. 2000.-N 6.-P.45-46.

- Vasilyeva, N.P. Possibilities of echography in congenital pyloric stenosis / N.P. Vasilyeva, M.Kh. Arslanova, T.M. Shakhmaeva // Ultrasound diagnostics. – 1997. – No. 4. – P. 11.

Functional gastrointestinal disorders in infants: methods of correction

Functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) imply the presence of clinical symptoms in the absence of organic changes in the gastrointestinal tract (structural abnormalities, inflammatory changes, tumors, infections). Typically, functional disorders are associated with changes in motor function and somatic sensitivity, deviations in the secretory and absorption functions of the digestive system [1]. The most common functional gastrointestinal disorders in children of the first year of life are: regurgitation syndrome and functional constipation.

Regurgitation syndrome refers to the reflux of stomach contents into the oral cavity.

The prevalence of regurgitation in children of the first year of life, according to a number of researchers, ranges from 18 to 50% [2, 3, 4]. Most often, regurgitation is observed in the first 4–5 months of life.

The high frequency of regurgitation in infants is due to the structural features of the upper digestive tract, the immaturity of the neurohumoral link of the sphincter apparatus and gastrointestinal motility.

Regurgitation in children of the first year of life is most often caused by the following reasons.

Regurgitation without organic changes in the gastrointestinal tract:

- rapid sucking, aerophagia, overfeeding, violation of feeding schedule, inadequate selection of formulas, etc.;

- perinatal damage to the central nervous system (CNS);

- early transition to thick foods;

- pylorospasm.

Regurgitation caused by organic lesions:

- pyloric stenosis;

- malformations of the gastrointestinal tract [5].

Currently, it is customary to evaluate the intensity of regurgitation on a five-point scale, reflecting the overall characteristics of the frequency and volume of regurgitation [6].

In most children, regurgitation can be considered as a certain variant of the body’s normal reaction, since it does not lead to pronounced changes in the child’s health. The relevance of correcting regurgitation syndrome is due to possible complications of this condition (disturbances in weight and height indicators, anemia, esophagitis, aspiration pneumonia, sudden death syndrome), deterioration in the quality of life of the child’s family, possible long-term effects on the health of children, and the lack of a clear clinical picture between normal and pathological conditions. [3, 7, 8].

In some cases, children with persistent regurgitation (from 3 to 5 points) not only have a delay in physical development, but are also diagnosed with iron deficiency anemia, as well as a high incidence of gastrointestinal and respiratory diseases under the age of 3 years. Persistent regurgitation can be a manifestation of both pathological gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Pathological GER is defined as frequent and prolonged reflux of acidic contents into the esophagus, the development of an inflammatory reaction of the esophageal mucosa with pronounced clinical manifestations.

In children in the first 3 months of life with regurgitation syndrome, physiological GER is diagnosed in 40-70%, and pathological in only 1-2%. In children 4–12 months of age, the frequency of pathological reflux and GERD increases to 5%.

Clinically, pathological reflux and GERD in children of the first year of life is manifested by regurgitation (regurgitation), vomiting, decreased body weight gain, possible respiratory disorders (prolonged cough, recurrent pneumonia), otolaryngological problems (otitis media, stridor (chronic or recurrent), laryngospasm, chronic sinusitis, laryngitis, laryngeal stenosis), as well as restless sleep and excitability.

24-hour intraesophageal pH-metry is recognized as the most informative method for examining children suffering from persistent regurgitation from a differential diagnostic point of view. This method allows you to identify the total number of reflux episodes, their duration, and the level of acidity in the esophagus. According to pH-metry, with functional regurgitation (regurgitation), the pH in the distal esophagus can be below 4, but not more than 1 hour daily (less than 4% of the total monitoring time); with GER, the pH in the distal esophagus reaches 4, exceeding 4 .2% of the total monitoring time, and in case of pathological reflux its duration exceeds 5 minutes [9].

A diagnostic method such as esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGDS) with targeted biopsy of the esophageal mucosa is also used. This examination allows you to assess the nature of the mucous membrane, the consistency of the cardiac sphincter, etc. Histological examination allows you to determine the severity of the inflammatory process as early as possible.

When examining children with regurgitation syndrome for the purpose of differential diagnosis, other instrumental examination methods are used: esophagotonokymography (allows for analysis of the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and the state of motor function of the stomach, amplitude of contractions), scintigraphy (allows for assessing the slowdown of esophageal clearance). In case of GER, accompanied by a delay of the isotope in the esophagus for more than 10 minutes, radiography is necessary to determine the reflux of the contrast agent from the stomach into the lumen of the esophagus, as well as to identify a hiatal hernia, which can cause persistent regurgitation and vomiting.

Treatment of regurgitation syndrome and GER includes the following main approaches:

- outreach, psychological support for parents;

- diet therapy, use of thickeners;

- positional (postural) therapy; prescription of drugs (medicines) - antacids, alginates, prokinetics;

- use of H2-histamine receptor blockers (ranitidine, famotidine);

- surgical methods of treatment [10].

Treatment of regurgitation in infants should be comprehensive, more and more intense from stage to stage (Step-up therapy), and if an effective result is obtained, a gradual reduction in the activity of treatment (Step-down therapy) is indicated.

Postural therapy is aimed at reducing the degree of reflux. It helps cleanse the esophagus of gastric contents, reducing the risk of esophagitis and aspiration pneumonia. Feeding the baby should be done in a sitting position, at an angle of 45–60°. Keeping the baby in an upright position after feeding should be as long as possible, at least 20–30 minutes. Postural treatment should be carried out not only throughout the day, but also at night, when the clearing of the lower esophagus from aspirate is impaired due to the absence of peristaltic waves (caused by the act of swallowing) and the neutralizing effect of saliva.

Postural therapy must be combined with psychological support for parents.

A significant role in the treatment of regurgitation belongs to diet therapy, the choice of which depends on the type of feeding of the child.

When breastfeeding, first of all, it is necessary to create a calm environment for the nursing mother, aimed at maintaining lactation, normalizing the child’s feeding regimen in order to avoid overfeeding and the development of aerophagia. According to some authors, regurgitation and GER can be a manifestation of food intolerance, therefore, if necessary, the mother is prescribed a hypoallergenic diet. Regurgitation may be caused by neurological disorders due to perinatal damage to the central nervous system - in this case, dietary correction should be combined with drug treatment prescribed by a neurologist.

If there is no effect from the measures described above, with persistent regurgitation, breast milk thickeners or denser foods are used before feeding. At the same time, dairy-free rice porridge or rice water (preferably commercially produced) is added to a small portion of expressed breast milk.

Even persistent regurgitation is not an indication for transferring a child to mixed or artificial feeding. Typically, by 3 months, the number of regurgitation episodes decreases significantly. If persistent regurgitation persists, this means that the child needs additional examination and the prescription of diet therapy in combination with medication.

When artificial feeding, it is also necessary to pay attention to the child’s feeding regimen, the adequacy of the selection of milk formulas, their volume, which should correspond to the age and body weight of the child. The child should receive an adapted milk formula. Preference is given to casein-dominant milk formulas, since casein forms a denser clot in the stomach, which slows down gastric emptying and reduces the motor activity of the colon. If GER is a manifestation of food intolerance, one of the hypoallergenic mixtures should be prescribed.

In the absence of positive dynamics, the child is recommended one of the types of specialized food products - anti-reflux milk formula, the viscosity of which increases due to the introduction of specialized thickeners into the composition of the products [11, 12, 13]. Two types of polysaccharides are used as such thickeners:

- indigestible (gum, which forms the basis of carob gluten);

- digestible (modified rice starch).

Antireflux mixtures are well tolerated; their composition meets the children’s needs for all essential nutrients and energy (Table).

Antireflux mixtures should be used differentially, depending on the thickeners they contain, as well as on the child’s health condition. Mixtures containing gum are more indicated for intense regurgitation (3–5 points). These products also have some laxative effects due to the effect of indigestible carbohydrates on intestinal motility. Formulas can be recommended in full or as a replacement for part of the feeding. In this case, the amount of formula needed by the child and the duration of its administration are determined by the speed of onset of the therapeutic effect.

Mixtures containing starch as a thickener act somewhat “softer”; the effect of their use manifests itself over a longer period compared to products containing gum. These mixtures are indicated for children with less pronounced regurgitation (1–3 points), both with normal stool and with a tendency to unstable stool. It is advisable to recommend starch-containing formulas as a complete replacement for previously obtained milk formula [14].

Conducted studies have proven the positive effect of diet therapy using specialized antireflux mixtures on reducing the severity of regurgitation syndrome in infants, both according to clinical and intragastric pH measurements. In most children, when using these mixtures, there was a decrease in the frequency, duration and severity of reflux in the esophagus [4]. However, the change in the acid-forming function of the stomach when using products with various thickeners is not the same: in children who received mixtures containing starch, acid formation in the body of the stomach decreased, and when using mixtures containing gum, on the contrary, it increased - against the background of reduced acidity in the esophagus and cardiac section of the stomach. This, with a certain degree of probability, suggests that children with regurgitation syndrome and a tendency towards a hypo- and anacid state of the stomach should be recommended antireflux mixtures containing gum, and patients in a hyperacid state should be recommended antireflux mixtures containing starch. However, this issue requires further study.

Despite the high clinical effectiveness of antireflux formulas, they should not be used uncontrolled as an alternative to adapted milk formulas. These mixtures are used at a certain stage in the treatment of regurgitation, for certain indications. The duration of use should be determined individually; after achieving a stable therapeutic effect, the child is transferred to an adapted milk formula.

If diet therapy is ineffective, it must be combined with drug treatment [15, 16]. The following medications are used to treat regurgitation syndrome.

- Antacids (phosphalugel, Maalox) - course of treatment 10–21 days; 1/4 sachet or 1 teaspoon after each feeding - for children under 6 months; 1/2 sachet or 2 teaspoons after each feeding - children 6–12 months.

- Prokinetics - metoclopramide (cerucal, raglan); cisapride (Prepulsid, Coordinax); domperidone (Motilium) - course of treatment for 10–14 days; 0.25 mg/kg - 3-4 times a day 30-60 minutes before meals. Metoclopramide drugs have a pronounced central effect (pseudobulbar disorders have been described) and are not recommended for use in infants with regurgitation syndrome. When using cisapride drugs, prolongation of the QT interval in children has been described, which serves as a limitation on the use of such drugs.

In the presence of pathological GER, manifested by regurgitation, the drugs of choice are H2-histamine receptor blockers: a course of treatment of up to 3 months with gradual withdrawal, ranitidine - 5-10 mg/kg per day; famotidine - 1 mg/kg per day.

Functional constipation is one of the most common disorders of intestinal function and is detected in 20–35% of children in the first year of life [1, 16].

Constipation is understood as defecation disorders, which are manifested by an increase in the intervals between bowel movements compared to the individual physiological norm and/or with systematic incomplete bowel movement [17].

The following diagnostic criteria for constipation exist:

- prolongation of intervals between acts of defecation (more than 32–36 hours);

- long period of straining - at least 25% of the total time of defecation;

- the consistency of stool is “dense”, in the form of lumps;

- feeling of incomplete bowel movement [18, 19].

The occurrence of constipation is caused by dyskinesia of the colon (hypo- and hypermotor disorders), a violation of the act of defecation - dyschesia (spasm of the rectal sphincters, weakening of smooth muscles, etc.) or a combination of these factors.

Depending on the etiology, the following types of constipation are distinguished: nutritional; neurogenic; infectious (after an infection); inflammatory; psychogenic; arising as a result of developmental anomalies of the large intestine (congenital megacolon, mobile cecum or sigmoid colon, dolichosigma, etc.); toxic; endocrine (hyperparathyroidism, hypothyroidism, pituitary disorders, diabetes mellitus, pheochromocytoma, hypoestrogenemia); medicinal (use of anticonvulsants, antacids, diuretics, iron and calcium supplements, barbiturates) [20]. According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 95% of children with constipation have no organic pathology [21].

Risk factors for the development of constipation in children in the first year of life include early artificial feeding, perinatal damage to the central nervous system, prematurity, morphofunctional immaturity of the newborn, food intolerance, intestinal dysbiosis, and a family history of gastrointestinal diseases [22, 23].

The mechanism of development of constipation during this period is such that it can be argued that they are caused primarily by dyskinesia of the large intestine. The most common cause of constipation in children of the first year of life is nutritional disorders. Treatment of functional constipation in children of the first year of life includes diet therapy and, if necessary, drug treatment. The purpose of diet therapy depends on the type of feeding.

Basic principles of diet therapy in children of the first year of life:

- satisfying the child’s physiological needs for nutrients and energy;

- avoiding excess consumption of proteins and fats, which can inhibit intestinal motility;

- enriching the diet with dietary fiber;

- normalization of intestinal microflora (use of pre- and probiotics) [17].

In breastfed children, it is necessary to normalize the child's diet to avoid overfeeding. Considering the fact that the composition of breast milk to a certain extent depends on the mother’s diet, it is necessary to correct the woman’s diet. From the mother's diet, foods high in animal fats should be excluded as much as possible, replacing them with vegetable oils. There is a direct correlation with the occurrence of constipation in children with constipation in the mother in the postpartum period, therefore, in the diet of a nursing woman it is necessary to include foods that stimulate intestinal motility - fermented milk products, foods high in nutrients (vegetables, fruits, dried fruits, cereals, bread coarse grinding, etc.), it is necessary to maintain an optimal drinking regime.

Since constipation in children in the first months of life is often a manifestation of the gastrointestinal form of food allergy, foods with a high allergic potential should be removed from the mother’s diet, especially cow’s milk, fish, and nuts, the consumption of which is the most common cause of food allergy in children in the first year of life [ 22].

Functional constipation in children receiving natural feeding is not an indication for transferring the child to mixed or artificial feeding - this can only aggravate the problem.

The introduction of complementary feeding products into the diet of constipated children who are breastfed should be carried out, in accordance with the recommended feeding schedule, no earlier than 4–5 months of life. Complementary feeding in children with functional constipation should begin with the introduction of foods high in dietary fiber: fruit juices with pulp (apple, plum, prune, apricot, etc.), fruit purees from the same fruits, then vegetable purees (zucchini puree, cauliflower cabbage, etc.), grain complementary foods - buckwheat, corn porridge.

If there is no effect from the dietary correction, it must be combined with drug therapy - lactulose preparations (Duphalac, Normaze, Lactusan, etc.). Duphalac is 6.7% lactulose, the recommended dose of the drug is 0.5 ml/kg/day in one dose, in the morning with meals; the dose is increased if clinical improvement is not observed within 2 days of taking the drug; if necessary, a double dose is used. Lactusan is available in tablets and syrup form, which is used 5 ml 2-3 times a day for 1-2 weeks. To correct intestinal dysbiosis, preparations containing probiotics are used [1].

When artificial feeding, it is necessary to correct the child’s diet and the volume of formula received to avoid overfeeding. The formula that the child receives should be maximally adapted in terms of protein and fat levels. For children with constipation, we can recommend mixtures that contain oligosaccharides, which have a pronounced prebiotic effect and also somewhat stimulate intestinal motility. The diet of children should include fermented milk products, which also stimulate intestinal motility (in the first months of life - adapted, the child can receive whole kefir starting from 8-10 months of life).

If these measures are insufficiently effective for the child, it is necessary to select one of the specialized milk formulas intended for feeding children with constipation. These mixtures include: milk formulas containing lactulose; milk formulas containing an indigestible polysaccharide - galactomanan, which is obtained from carob gluten; milk formulas intended for children with functional gastrointestinal disorders.

The therapeutic effect of mixtures containing lactulose (Samper Bifidus mixture, Samper, Sweden) lies in the fact that lactulose, an isomer of milk sugar (lactose), is not broken down by the enzyme lactase and enters unchanged into the lower intestines, where it serves as a substrate for bifidobacteria and lactobacilli. As a result of the metabolization of lactulose by bifidobacteria and lactobacilli, short-chain fatty acids (acetic, propionic, butyric, etc.) are formed, which, by changing the pH in the intestinal lumen to the acidic side, affect the receptors of the colon and stimulate its peristalsis. In addition, low-molecular compounds create increased osmotic pressure in the intestinal lumen, ensuring the retention of additional fluid in the chyme and facilitating easier bowel movement [24, 25].

This mixture can be recommended for daily feeding in full or in an amount of 1/3–1/2 of the required volume at each feeding, in combination with a regular adapted milk formula. The mixture is prescribed until a stable therapeutic effect is achieved. After this, the question of the advisability of continuing to feed a formula with lactulose should be decided individually, depending on the child’s condition [26].

Formulas containing the indigestible polysaccharide galactomanan from carob gluten were originally developed for children with regurgitation problems, as galactomanan increases the viscosity of the formulas and reduces regurgitation. However, galactomanan, like lactulose, without being broken down in the upper sections of the intestine, enters unchanged into its lower sections and, irritating the receptors of the colon, stimulates its motor activity. An example of a mixture containing galactomanan is Friesov 1 (Friesland Foods, The Netherlands). The mixture can be recommended either in full or in part, in an amount of 1/3–1/2 of the required volume at each feeding, in combination with a regular adapted milk formula, until a lasting therapeutic effect is achieved.

The effectiveness of the mixture intended for children with functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract - "Nutrilon Comfort" (Nutrition, the Netherlands) is due to the vegetable oils included in its composition, the triglycerides of which contain palmitic acid in the second position, which ensures a higher attackability of fat and reduces the content of calcium in the intestines soaps that promote constipation. The mixture also contains fructo- and oligosaccharides, pregelatinized starch, which have prebiotic properties. It is advisable to recommend the mixture in full daily volume until a stable therapeutic effect occurs.

Children with functional constipation who are bottle-fed should receive complementary foods in accordance with the recommended feeding schedule. The first foods you should give your child are foods high in dietary fiber (fruit juices, fruit and vegetable purees).

Literature

- Khavkin A.I. Functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract in young children. M., 2000. 71 p.

- Zaprudnov A. M. Handbook of pediatric gastroenterology. M., 1995. pp. 25–26.

- Vandenplas Y., Ashrenari A., Belli D., Baige Bouqnet J. et al. A proposition for the diagnosis and treatment of gastro-esophageal reflux disease//Eur. J. Pediatric. 1993; 152:704–711.

- Khorosheva E.V. Nutritional correction of regurgitation syndrome in children of the first year of life: abstract. dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 2001. 26 p.

- Guide to baby nutrition / ed. V. A. Tutelyan, I. Ya. Konya. M., 2004. 441 p.

- Vandenplas Y., Hachimi-Idrissi S., Castells A. et al. A clinical trial with an “anti-regurgitation” formula//Eur. J. Pediatric. 1994; 153:419–426.

- Svirsky A.V. Gastroesophageal reflux in newborns: abstract. dis. ...cand. honey. Sci. M., 1991. 23 p.

- Khorosheva E.V., Sorvacheva T.N., Kon I.Ya. Regurgitation syndrome in infants // Nutrition Issues. 2001. No. 5. pp. 32–34.

- Stodal K., Bentsen B., Skulstad H., Moum B. Reflux disease and 24-hour oesophageal pH monitoring in children//Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforw. 2000; 120:2:183–186.

- Vandenplas Y. A critical appraisal of current management practices for infant regurgitation//Chung. Hua. Min. Tsa. Chin. 1997; 38:3:187–202.

- Kon I. Ya., Sorvacheva T. N., Khorosheva E. V. et al. New approaches to dietary correction of regurgitation syndrome in children // Pediatrics. 1999. No. 1 P. 60–63.

- Fabiani E., Bolli V., Pieroni G. et al. Effect of water-soluble fiber (Galactomannan) — enriched on gastric emptying time of regurgitation infants evaluated using an ultrasound technique//J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 2000; 31: 248–250.

- Frederic Gottrand. The occurrence and nutritional management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants//Nutricia Baby Food Symposium, ESPGHAN 2 June 2005; 3–4.

- Kon I. Ya., Sorvacheva T. N., Pashkevich V. V. Modern approaches to dietary correction of regurgitation syndrome in children: a manual for pediatricians. M., 2004. P. 16.

- Kornienko E. A., Shabalov N. P., Erman L. V. Diseases of the digestive organs: childhood diseases. 5th ed. St. Petersburg, 2001. 326 p.

- Guide to baby nutrition / ed. V. A. Tutelyan, I. Ya. Konya. M., 2004. 453 p.

- Frolkis A.V. Functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. L.: Medicine, 1991. P. 224.

- Hammad E.V. Constipation: modern problems//Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology. 1999. No. 5. T. 9. P. 61–64.

- Drossman DA, Punch-Jensen J. et al. Identification of subgroups of constipation//Gastroenterol. Int. 1996; 3: 159–172.

- Pediatric gastroenterology//ed. A. A. Baranova, E. V. Klimanskaya, G. V. Rimarchuk. M., 2002. Izbr. Ch. pp. 499–530.

- University of Michigan Medical Center. Idiopathic constipation and soiling in children. Ann Arbor (MI): University of Michigan Health System; 1997; 5.

- Borovik T. E. Medical and biological foundations of diet therapy for food intolerance in young children: abstract. dis. ...Dr. med. Sci. M., 1994. P. 40.

- Korovina N. A., Zakharova I. N., Malova N. E. Constipation in young children // Pediatrics. 2003. T. 5. No. 9. P. 1–13.

- Tamura Y., Mizotal., Shimamura S., Tomita M. Lactulose and its application to the food pharmaceutical industry//Bull. Int. Dairu. Fed. 1994; 289:43–53.

- Potapov A. S., Polyakova S. I. Possibilities of using lactulose in the treatment of chronic constipation in children // Issues of modern pediatrics. 2003. No. 2. P. 65–70.

- Sorvacheva T. N., Pashkevich V. V., Efimov B. A., Kon I. Ya. Clinical effectiveness of using the Samper Bifidus mixture in children in the first months of life with functional constipation // Children's Doctor. 2001. No. 1. P. 27–29.

T. N. Sorvacheva , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor V. V. Pashkevich RMAPO, Moscow