Weakness of the sphincter, that is, partial or complete incontinence of feces, is a problem for a person suffering from this disease. Strong feelings and worries about their delicate symptoms can lead the patient to nervous disorders. However, with timely consultation with a doctor, sphincter weakness can generally be successfully treated. There are many different techniques that can significantly improve the patient's condition. In addition to the weakness of the anal sphincter in patients, there may be pathologies such as insufficiency of the bladder sphincter, which causes urinary incontinence and weakness of the cardiac sphincter (separates the stomach cavity from the esophagus), manifested by pain in the chest, heartburn and other symptoms.

Anal sphincter weakness

Insufficiency of the anal sphincter (photo: tutknow.ru)

The sphincter (sphincter) is an anatomical structure consisting of a circular muscle that is capable of contracting, that is, being in a relaxed or tense state. Its main function is to move contents from one hollow organ to another. For example, the lower esophageal sphincter (cardiac sphincter) allows food to pass from the esophagus into the stomach cavity, the bladder sphincters ensure urination and control urinary retention. Insufficient work of the pulp is a pathology that requires treatment.

The human rectum is the end of the digestive tract, ending with the anus, around which the external and internal sphincters are located. Normally, they are able to retain feces and gases under any stress (sneezing, exercise, coughing, diarrhea). However, due to the action of various negative factors, atrophy of muscle fibers and disruption of their motor function may occur. The most common causes that cause weakness of the anal sphincter are pathological conditions such as:

- Injuries.

- Congenital anomalies (pathologies in the sacral spine, underdevelopment of the anal canal).

- Surgical interventions.

- Perineal rupture during childbirth.

- Chronic pathologies of the colon (hemorrhoids, proctitis).

- Organic changes in the brain (brain tumors, traumatic brain injuries, cerebrovascular accidents).

- Hernias in the lumbar and sacral spine.

- Age-related changes (menopause in women).

Depending on the severity of the pathological process, weakness of the anal sphincter manifests itself with the following symptoms:

- Uncontrolled release of liquid feces during diarrhea, inability to contain gases (initial stages of the disease).

- Involuntary discharge of hard feces (third degree of anal sphincter weakness).

- Itching in the anal area.

- Flatulence.

- Lack of urge to have a bowel movement. This symptom is often a sign of organic brain damage, hernias in the lumbar and sacral spine. It may also be associated with various damage to the receptors of the lower colon.

Treatment and diagnosis of anal sphincter insufficiency

Diagnostic method - sigmoidoscopy (photo: seolite.ru)

A proctologist diagnoses and treats weakness of the rectal sphincter. After a digital examination, to differentiate the diagnosis, the doctor may prescribe such types of functional diagnostics as:

- Sphincterometry (to study the strength of contractions of the rectal sphincter in different areas, helps determine the localization of the problem area).

- Electromyography (to determine the tone and condition of muscle tissue).

- Anoscopy (visual assessment of the anal canal).

- Sigmoidoscopy (examination of the rectum using a rectoscope).

- X-ray with contrast agent (helps to understand the severity of the pathological process).

Treatment of anal sphincter weakness consists of the following methods:

- Review your diet. Add foods rich in fiber - legumes, wheat bran, rye bread, nuts. As well as fresh fruits, vegetables, herbs. Eliminate alcohol and coffee.

- If the weakness of the anal sphincter is caused by systematic diarrhea, it can be eliminated with drugs such as Loperamide, Belladonna, Activated Charcoal, Kaopectate (after consulting a doctor).

- Special exercises aimed at rhythmic contraction of the pelvic muscles can strengthen not only the anal sphincter, but also the bladder sphincter.

- Electrical stimulation of muscles using a rectal probe (electrode), which is inserted into the anus. It can be carried out by the patient independently at home with a portable device (electrical stimulator).

- Bifeedback therapy. Using a special device, the patient is trained to control the pelvic floor muscles.

- Drug therapy aimed at eliminating inflammatory processes in the large intestine.

- Surgical treatment (sphincteroplasty, artificial sphincter implantation).

All of the above methods and drugs should be used only after consultation with a proctologist.

Important! Sphincter weakness is a very serious problem and can lead to disability. You should not self-medicate and put off visiting a doctor. For any manifestations of fecal incontinence, you should contact a specialist.

Cardiac sphincter insufficiency (gastric cardia)

Pain in the chest and heartburn with weakness of the cardiac sphincter (photo: mojzheludok.com)

The human stomach is connected to the esophagus through the cardiac sphincter, and through the pyloric sphincter it is connected to the duodenum. The main function of the esophageal sphincter is to retain food in the stomach cavity, preventing gastric juice, particles of undigested food and bile from entering the esophagus. With systematic overeating, obesity, chronic inflammatory processes (gastritis, ulcers), a sedentary lifestyle, and the habit of eating large amounts of food before bed, weakness of the cardiac sphincter may occur, which is manifested by the following symptoms:

- Heartburn.

- Belching.

- Nausea, vomiting.

- General malaise, increased fatigue.

- Burning pain in the chest.

- Hernia in the diaphragm area.

A gastroenterologist treats and diagnoses the disease. First of all, it is necessary to determine the cause of gastric cardia. After prescribing the main treatment, you need to organize the patient’s correct diet - eat at the same time, in small portions, 5-6 times a day, do not lie down for two hours after eating. The consumption of alcohol, coffee, strong tea, spicy and fatty foods is prohibited.

Bladder sphincter weakness

Urinary incontinence (photo: medweb.ru)

Bladder sphincter insufficiency mainly occurs due to weakness of the pelvic floor muscles (after childbirth, lack of physical activity, obesity). Chronic inflammatory processes in the bladder itself (cystitis) can provoke weakness of its sphincters. Women most often suffer from this disease. The disease manifests itself with the following symptoms:

- Uncontrolled urine output during physical activity.

- Voluntary frequent urination at rest.

- Constant feeling of bladder fullness.

- The release of small portions of urine when coughing, sneezing, running, jumping.

Treatment and diagnosis of the disease is carried out by a urologist.

Prevention

Kegel exercises during pregnancy to strengthen the pelvic floor muscles (photo: woman365.ru)

Any feasible physical activity is very useful for all of the above pathologies, including gastric cardia. Weakness of the pelvic floor muscles and insufficiency of the anal sphincters will help eliminate Kegel gymnastics. The general principle of performing exercises for beginners is the following:

- Take any comfortable position.

- Squeeze and pull up all the pelvic floor muscles for 5-10 seconds.

- On the count of ten, relax.

- The exercise should be repeated ten times 3-4 times a day. The success of this method lies in its regularity. Irregular chaotic movements can lead to the opposite effect - an imbalance of the pelvic floor muscles.

Also, you should avoid hypothermia, inadequate physical activity, and systematic overeating. It is necessary to promptly treat all inflammatory processes in the body and consult a doctor if there is any discomfort.

Sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome

A significant proportion of patients after cholecystectomy develop sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SDO) [1, 3].

According to the Rome Consensus III (2006), dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi is understood as a violation of its contractile function, preventing the normal outflow of bile and pancreatic secretions into the duodenum [10].

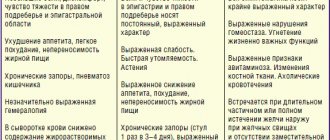

Abdominal pain syndrome

It is believed that in the first month after cholecystectomy, hypertonicity of the sphincter of Oddi predominates in more than 80% of patients, which is associated with the switching off of the regulatory role of the Lutkens sphincter [1, 3]. Pain syndrome in the presence of sphincter dysfunction in most cases is caused by spasm of the sphincter of Oddi.

Diagnostic criteria for sphincter of Oddi dysfunction [10]:

1) episodes of severe pain localized in the epigastrium or right hypochondrium, in combination with all of the following signs; 2) duration 30 minutes or more; 3) frequency of symptoms: 1 time or more in the last 12 months; 4) the pain intensity is significant: it interferes with daily activity and requires seeking medical help; 5) there are no structural changes that explain the pain.

It should be remembered that clinical symptoms (primarily abdominal pain) after removal of the gallbladder are observed in 70–80% of cases and can be caused by a whole group of reasons, among which the most significant are: diagnostic errors made at the preoperative stage during the examination of the patient and /or during surgery; exacerbation or progression of diseases of the hepatopancreatobiliary zone that existed before the operation, technical errors and tactical errors made during the operation [3]. Clinical symptoms may be due to undiagnosed and uncorrected diseases that existed in the preoperative period (chronic liver diseases, strictures, biliary stenoses, both congenital and acquired, bile duct stones, cholangitis, pancreatitis, benign and malignant tumors of the pancreas, especially with localization of the process in the region of the head, diseases of the stomach and duodenum, including erosive and ulcerative changes, as well as para- and peripapillary diverticula of the duodenum. Errors made during cholecystectomy: undetected stones in the common bile duct, damage to the ducts, leaving a long cystic stump duct, etc. [3].

For these reasons, making a diagnosis of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction requires a thorough examination of the patient. Laboratory tests (general blood count, determination of levels of gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alkaline phosphatase, bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, amylase) and instrumental diagnostic methods (ultrasound, esophagogastroduodenoscopy, duodenography) are used as screening diagnostic methods. The use of highly informative diagnostic methods (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance cholangiography, endoscopic ultrasonography, etc.) allows for timely and adequate correction of anatomical and functional disorders that developed after cholecystectomy or aggravated by it. To confirm dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, endoscopic sphincter manometry is used [1, 3, 6].

In 2006, a working group of experts on functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) prepared the Rome Consensus III, according to which section E “Functional disorders of the sphincter of Oddi” included sections: E2 “Functional disorder of the biliary and pancreatic types” [10] .

Patients with the biliary type of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction are divided into three groups presented in the table, the management tactics of which differ significantly.

A similar classification is used in patients with pancreatic type of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction. In these cases, great importance is attached to at least a twofold increase in the level of pancreatic enzymes in the blood during two consecutive attacks of pain, as well as dilation of the pancreatic duct by more than 5 mm.

Patients of group 1, who have sphincter of Oddi stenosis and a high probability of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (> 70%), undergo endoscopic sphincterotomy without preliminary manometric examination, which reduces the incidence of complications.

In patients of group 2, only in 50% of cases, a manometric study reveals dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi. Most researchers believe that this group of patients needs to undergo preliminary drug treatment and only if it is ineffective, conduct manometry of the sphincter of Oddi.

In the 3rd group of patients, the causes of pain in most cases are due to dyskinesia of the sphincter of Oddi, and, therefore, manometry of the latter is not indicated.

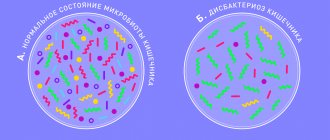

Bacterial overgrowth syndrome and intestinal bile acid metabolism

In the presence of a spasm of the sphincter of Oddi during the digestive period, the passage of bile through the intestines is disrupted, accompanied by various manifestations of digestive disorders. Irregular supply of bile acids disrupts the enterohepatic circulation of bile acids, the digestion and absorption of fats, reduces the bactericidal properties of duodenal contents, contributing to disruption of the microbiocenosis of the small intestine. In case of insufficiency of the sphincter of Oddi, which, in the absence of a reservoir function of the gallbladder, is not able to withstand increased pressure (more than 300–350 mm of water column) in the common bile duct, there is a constant flow of bile acids into the intestine, which may cause the development of cholagenic diarrhea [ 3, 12].

It should be noted that with both types of dysfunction (spasm, insufficiency), a number of symptoms are observed indicating a disturbance in the metabolism of bile acids in the intestine (dyspeptic symptom complex). The main role in the development of these disorders belongs to changes in the composition of the intestinal microflora.

In a healthy person with a gallbladder, primary bile acids synthesized in hepatocytes are excreted into bile conjugated with glycine or taurine and enter the gallbladder through the biliary tract, where they accumulate [4]. A small amount of bile acids is absorbed in the walls of the gallbladder - about 1.3%. In a healthy person with a gallbladder, the main pool of bile acids is located in the gallbladder, and only after stimulation by food does the gallbladder reflexively contract and bile acids enter the duodenum. Secondary bile acids—deoxycholic and lithocholic—are formed from primary bile acids (chole- and chenodeoxycholic, respectively) under the influence of anaerobic bacteria of the colon (Fig. 1).

After reabsorption of secondary bile acids, they are conjugated with glycine or taurine, and they also become components of bile. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is a tertiary bile acid that does not exceed 5% of all bile acids in the human body and is also formed under the action of microbial enzymes [13].

From the intestine, bile acids with the portal blood flow again enter the liver, which absorbs almost all bile acids (approximately 99%) from the portal blood; a very small amount (about 1%) enters the peripheral blood (Fig. 2).

Active absorption of bile acids occurs in the ileum of the small intestine, while passive absorption occurs due to the concentration of bile acids in the intestine, since it is always higher than in the portal blood. In hepatocytes, toxic free bile acids, accounting for approximately 15% of the total amount of bile acids absorbed into the blood, are converted into conjugated ones. From the liver, bile acids return to bile in the form of conjugates. Such enterohepatic circulation in the body of a healthy person occurs 2–6 times a day, depending on the diet; 10–15% of all bile acids entering the intestine after deconjugation undergo deeper degradation in the lower parts of the small intestine. As a result of oxidation and reduction processes caused by enzymes of the colon microflora, the ring structure of bile acids breaks down, which leads to the formation of a number of substances released into the external environment. Considering that bile acids normally prevent the development of excessive microbial growth in the intestine, in patients after cholecystectomy they are also considered as one of the causes of the development of this syndrome, as well as classical damaging factors in relation to the mucous membrane of the stomach, esophagus, and intestines. The damaging effect of bile acids depends not only on their concentration, but also on conjugation and environmental pH, the latter two processes being provided by the intestinal microflora. Bile acids, which have detergent properties, promote the solubilization of lipids in the membranes of surface epithelial cells. Soluble bile acids penetrate into epithelial cells. Intracellular concentrations of bile acids can be 8 times higher than their extracellular concentrations. Such excessive accumulation leads to increased permeability of cell membranes, their destruction, damage to intercellular contacts and ultimately to cell death [4, 14]. This damaging effect depends not only on the concentration of bile acids in the refluxate, but also on the length of time that the mucous membrane is exposed to bile. Under the influence of bile acids, the amount of phospholipids decreases, and the hydrophobicity of mucus is lost [4, 9]. Conjugated bile acids have a negative effect at acidic pH values, and unconjugated bile acids have a negative effect at pH values of 5–8. For these reasons, when intestinal microbiocenosis is disrupted, unconjugated bile acids have a pronounced damaging effect on epithelial cells. Mature and immature goblet cells from the colon tissue of a healthy person undergo apoptosis under the influence of bile acids.

A study of the biological properties of bifidobacteria and lactobacilli has shown that the human microbiota population has a multifaceted range of physiologically beneficial effects. In relation to the problem under discussion, it is worth dwelling on some of them.

The intestinal microflora is directly involved in the metabolism and elimination of toxic bile acids, in particular cholic acid. Normally, conjugated cholic acid, which is not absorbed in the distal ileum, in the colon undergoes deconjugation by microbial choleglycine hydrolase and dehydroxylation with the participation of 7-alpha dehydroxylase [11, 12]. The resulting deoxycholic acid binds to dietary fiber and is excreted from the body. The pH in the intestinal lumen is of great importance. When the pH value increases, deoxycholic acid is ionized and well absorbed in the colon, and when it decreases, it is excreted. An increase in pH values in the colon leads to an increase in the activity of enzymes leading to the synthesis of deoxycholic acid, its solubility and absorption and, as a result, an increase in the level of bile acids, cholesterol and triglycerides in the blood. One of the reasons for the increase in pH may be a lack of prebiotic components in the diet, which disrupt the growth of normal microflora, including bifidobacteria and lactobacilli.

No less important are the effects associated with the synthesis of short-chain fatty acids (SCFA) as a result of anaerobic fermentation of di-, oligo- and polysaccharides accessible to bacteria [11, 12]. Locally, SCFAs determine a decrease in pH, providing intestinal colonization resistance, and take part in the regulation of intestinal motility. In addition, SCFAs are important for the epithelium of the colon, since it is butyrate that colonocytes use to meet their energy needs. In addition, the decrease in pH associated with the formation of SCFAs leads to the formation of ammonium ions from ammonia formed in the colon during microbial metabolism of proteins and amino acids, which can no longer freely diffuse through the intestinal wall into the blood, but is excreted in the feces in the form of ammonium salts

The result of the joint symbiotic activity of intestinal epithelial cells and physiological microflora is the formation of a complex specific preepithelial structure - a mucosal barrier (biofilm, microbiological barrier), consisting of mucus, secretory IgA molecules, indigenous flora and its metabolites and protecting the intestinal mucosa from the action of bacterial and other toxins physical and chemical nature, including bile acids [11, 12].

Treatment of patients with sphincter of Oddi dysfunction

The main goal of treatment of patients with dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi is to restore the normal flow of bile and pancreatic juice from the biliary and pancreatic ducts into the duodenum using surgical or conservative treatment [1–3, 5–8].

In this regard, treatment objectives include:

- restoration, and if impossible, replenishment of bile production;

- restoration of the tone of the sphincter system;

- restoration of pressure in the duodenum (an adequate pressure gradient in the biliary tract depends on this).

Diet therapy occupies a significant place in the treatment of this category of patients. The general principle of the diet is a diet with frequent meals in small quantities (5-6 meals a day) with sufficient consumption of dietary fiber necessary to restore intestinal motor-evacuation function and correct microbiological disorders.

To relieve pain, smooth muscle relaxants are used, including several groups of drugs: anticholinergics - M-cholinergic blockers (belladonna preparations, platiphylline, Metacin, etc., due to pronounced side effects, the scope of application is limited), Buscopan (unlike the previous ones do not penetrate the blood-brain barrier and have low - 8-10% - systemic bioavailability); myotropic antispasmodics: non-selective (drotaverine, otilonium bromide, etc.) and selective - Mebeverine hydrochloride [2, 5, 8].

The drugs of choice for pathogenetic therapy of patients with functional diseases of the biliary tract are, of course, drugs that selectively relax the smooth muscles of the digestive organs, in particular mebeverine [2, 5, 8]. The advantage of the drug is its relaxing selectivity towards the sphincter of Oddi, which is 20–40 times greater than the effect of papaverine. Mebeverine has a normalizing effect on the intestinal muscles, eliminating functional duodenostasis, hyperkinesis, spasm, without causing the development of unwanted hypotension. The drug can be used long-term in this category of patients, in courses at a dose of 200 mg 2 times a day.

For the treatment of maldigestion and malabsorption syndromes, pancreatin preparations (Mikrazim, Creon, Panzinorm forte-N, Pancitrate and others) are prescribed.

Treatment of intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome

In the presence of microbial contamination of the small intestine, it is necessary to carry out decontaminating therapy (non-absorbable intestinal antibiotics - rifaximin, or intestinal antiseptics (nitrofuran series - Enterofuril, Ersefuril, fluoroquinolones, etc.) with the simultaneous and/or sequential use of probiotics and prebiotics (Hilak forte, Lactulose), drugs based on dietary fiber - Psyllium, etc.). The use of pro- and prebiotic drugs improves the metabolism of bile acids and stimulates the regeneration of intestinal wall epithelial cells damaged by deconjugated bile acids [3, 11].

In the presence of biliary insufficiency, UDCA drugs (Ursosan) are prescribed. The use of drugs in a daily dose of 10–15 mg/kg body weight reduces the degree of biliary insufficiency and the severity of dyscholia.

The pharmacological effects of UDCA (Ursosan) are varied. Regarding the problem under consideration, its following properties are of particular importance. First of all, it is hydrophilic and lacks toxic properties. UDCA displaces bile acids, which have a damaging effect on mucous membranes. When taken systematically, UDCA becomes the main bile acid in the blood serum and accounts for about 48% of the total amount of bile acids in the blood; there is a dose-dependent increase in its share in the pool of bile acids to 50–75%. This occurs, for example, due to competitive uptake of bile acid receptors in the ileum or due to the induction of bicarbonate-rich choleresis, which leads to increased passage of bile and increased excretion of toxic bile acids through the intestine. UDCA does not have a negative effect on cells (UDCA micelles practically do not dissolve membranes). The cytoprotective properties of UDCA are also of great importance from the point of view of protecting the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract. Under experimental conditions, UDCA has demonstrated an antioxidant effect [4, 13]. In addition, the use of UDCA helps prevent the development of bacterial overgrowth in the intestines. Timely and correct assessment of clinical symptoms using modern methods for diagnosing sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and prescribing adequate complex therapy can significantly improve the well-being and quality of life of this category of patients.

Literature

- Ardatskaya M.D. Functional disorders of the biliary tract (definition, classification, diagnostic and therapeutic approaches) // Handbook of a polyclinic doctor. 2010. No. 7.

- Ilchenko A. A. Efficacy of mebeverine hydrochloride in biliary pathology // Breast Cancer. 2003. No. 4.

- Ilchenko A. A. Gallstone disease. M.: Anacharsis, 2004. 200 p.

- Lapina T. L., Kartavenko I. M. Ursodeoxycholic acid: effect on the mucous membrane of the upper gastrointestinal tract // Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology. 2007. No. 6.

- Kosyura S. D., Fedorov I. G., Ilchenko L. Yu. The use of duspatalin in the complex therapy of functional disorders of the biliary tract and dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi // Consilium Medicum. Gastroenterology. 2010. No. 2.

- Loranskaya I. D., Vishnevskaya V. V., Malakhova E. V. Biliary dysfunctions - principles of diagnosis and treatment // Breast cancer. 2009. No. 4.

- Minushkin O. N. Functional disorders of the intestines and biliary tract. Therapeutic approaches, choice of antispasmodic // Attending Physician. 2012. No. 2.

- Toporkov A. S. Efficacy of selective myotropic antispasmodics for the relief of abdominal pain // Breast Cancer. 2011. No. 28.

- Allen A., Flemstrom G. Gastroduodenal mucus bicarbonate barrier: protection against acid and pepsin // Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 2005. Vol. 288. P. 1–19.

- Drossman DA The Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders and the Rome III Process // Gastroenterology. 2006; 130(5):1377–1390.

- Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Vuksan V. Inulin, Oligofructose and Intestinal Function // J. Nutr. 1999. Vol. 129. 1431 S–1433 S.

- Edwards CA, Parrett AM Intestinal flora during the first months of life: new perspectives // British Journal of Nutrition. 2002. 88, Suppl.1. S11–S18.

- Kawamura T., Koizimi F., Ishimori A. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid on water immersion resistant stress ulcer of rats // Nippon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 1989. Vol. 86. P. 2378–2388.

- Stein HJ, Kauler WK, Feussner H., Siewert JR Bile acids as components of the duodenogastric refluate: detection, relationship to bilirubin, mechanism of injury, and clinical relevance // Hepatogastroenterology. 1999. Vol. 46. P. 66–73.

E. A. Lyalukova, Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor M. A. Livzan, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education Omsk State Medical Academy of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation , Omsk

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Anal sphincter insufficiency (anal incontinence, anal incontinence)

Anal sphincter insufficiency (AS) is a condition in which a person is completely or partially unable to retain the contents of the rectum.

Causes:

- injuries of the obturator apparatus of the rectum;

- childbirth;

- neuro-reflex disorders;

- functional insufficiency of the anal sphincter, caused by pronounced changes in muscle structures (with rectal prolapse, hemorrhoids with prolapse of internal hemorrhoids, inflammatory diseases of the colon, malformations of the rectum and anal canal).

US classification

- By form: – organic; – inorganic (functional); – mixed.

- According to the location of the muscle defect around the circumference of the anal canal: – on the anterior wall; – back wall; – side wall; – several walls (combination of defects); - around the entire circumference.

- According to the degree of incontinence of intestinal contents (impaired continence function): – 1st degree – gas incontinence; – 2nd degree – incontinence of gases and liquid feces; – 3rd degree – incontinence of gases, liquid and solid feces.

- According to the length of the muscle defect along the circumference of the anal canal: – up to 1/4 of the circumference; – 1/4 circle; – up to 1/2 circle; – 1/2 circle; – 3/4 circle; - lack of sphincter.

Diagnostics

- Anamnesis collection. During a conversation with the patient, the doctor identifies possible causes of incontinence.

- The patient is examined on a gynecological chair. When examining the perineum and anus, concomitant diseases in this area are revealed - anal fissure, hemorrhoids, fistulas or rectal prolapse.

- Anal reflex assessment. Used to study the contractility of the sphincter muscles.

- Digital examination of the rectum.

- Sigmoidoscopy.

- Proctography with irrigoscopy.

- Functional studies of the obturator apparatus of the rectum.

– Anorectal profilometry. – Electromyography of the external sphincter and pelvic floor muscles is a method that allows you to assess the viability and functional activity of muscle fibers and determine the condition of the nerve pathways of the muscles of the obturator apparatus of the rectum. The result of the study plays an important role in predicting the effect of plastic surgery. - Endorectal ultrasound.

- You can find a more detailed description of diagnostic methods in the Diagnostics section.

Treatment

Conservative - aimed at improving the neuro-reflex activity of the obturator apparatus of the rectum and includes electrical stimulation, drug therapy and physical therapy;

Surgery . Indications:

- The impossibility of a radical cure for patients with anal sphincter insufficiency using conservative methods;

- insufficiency of the anal sphincter of the 2nd and 3rd degree, with a sphincter defect measuring 1/4 of a circle or more, in the presence of scar deformation of the walls of the anal canal;

- violation of the anatomical relationships of the muscles of the obturator apparatus.

Contraindications: damage to parts of the central and peripheral nervous system involved in the innervation of the pelvic organs and muscle structures of the perineum

What operations are used for NAS?

- Sphincteroplasty

- Sphincterolevatoplasty

- Sphincterogluteoplasty (replacement of the defect with a short flap of the gluteus maximus muscle)

- Gluteoplasty (formation of the sphincter with long flaps of the gluteus maximus muscle)

- Graciloplasty (formation of the sphincter with the tender muscle of the thigh)

- Implantation of artificial sphincter

- Injection method – injection of silicone biomaterials into the area of the sphincter defect under ultrasound control.

The choice of treatment method is made by a coloproctologist, taking into account the clinical situation and individual characteristics of the patient.

Go to

Gastroesophageal reflux disease. From pathology to clinic and treatment

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease;

- about the causes and mechanisms of development of esophageal reflux;

- about the differential diagnosis of chest pain;

- about modern principles of treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease and understand when to refer the patient to a surgeon.

Definition

Defining the concept of “gastroesophageal reflux disease” (GERD) is difficult because:

- in practically healthy people, reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus is observed;

- sufficiently prolonged acidification of the distal esophagus may not be accompanied by clinical symptoms and morphological signs of esophagitis;

- Often, with pronounced symptoms of GERD, there are no inflammatory changes in the esophagus.

By GERD, most researchers understand spontaneous, regularly repeated reflux of gastric or duodenal contents into the esophagus, which leads to damage to the distal esophagus and the appearance of characteristic symptoms (heartburn, retrosternal pain, dysphagia).

Epidemiology

The true prevalence of the disease has been little studied, which is associated with the wide variability of clinical manifestations - from occasional heartburn to clear signs of complicated reflux esophagitis. This was clearly shown by D. Castell (1985), who proposed the “iceberg” diagram of GERD. In most patients, the symptoms are mild and sporadic, they do not go to doctors, but take antacid medications on their own or use the advice of friends (“telephone” reflux) - this is the underwater part of the “iceberg”. The middle, surface part of the iceberg consists of patients with reflux esophagitis with severe or persistent symptoms, but without complications, who need regular treatment - “outpatient” reflux. Finally, the tip of the iceberg is patients who have developed complications (peptic ulcers, bleeding, strictures) - “hospital” reflux. Among US adults, the incidence of heartburn, the main symptom of GERD, is 20 - 40%, but only 2% receive treatment for reflux esophagitis (Spechler S., 1992). P. Jones (Great Britain, 1990), examining 7428 patients selected at random, noted the presence of heartburn in 40%, and 24% had suffered from heartburn for more than 10 years and only a quarter of them consulted doctors about this.

Pathophysiology

Since the pressure in the stomach is higher than in the chest cavity, reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus should be a constant phenomenon. However, due to the obturator mechanisms of the cardia, it occurs rarely, for a short time (less than 5 minutes) and, as a result, is not considered a pathology. Esophageal reflux should be considered pathological if the time during which the pH reaches 4.0 and below exceeds 4.2% of the total recording time (Fisher R„ Ogorek S., 1994). GERD is a multifactorial disease. J. Ferston et al. (1995) identify the following predisposing factors:

- stress;

- pose;

- obesity;

- pregnancy;

- smoking;

- hiatal hernia;

- medications (calcium antagonists, anticholinergic drugs, beta blockers, etc.).

The development of the disease is associated with a number of reasons:

- with insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter;

- with reflux of gastric and duodenal contents into the esophagus;

- with decreased esophageal clearance;

- with a decrease in the resistance of the esophageal mucosa.

The immediate cause of reflux esophagitis is prolonged contact of gastric (hydrochloric acid, pepsin) or duodenal contents (bile acids, trypsin) with the mucous membrane of the esophagus.

1. Insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES).

Gastroesophageal reflux is the result of a relative or absolute insufficiency of the obturator mechanism of the cardia. A significant increase in intragastric pressure leads to relative insufficiency of the cardia. For example, intense contraction of the antrum of the stomach can give rise to gastroesophageal reflux even in people with normal LES function. Relative insufficiency of the cardiac sphincter occurs in 9-13% of patients with GERD (Grebenev A. A., Nechaev V. M., 1995). Much more often there is absolute insufficiency of the cardia. The mechanisms that support the functionality of the area of the esophagogastric junction include (Maher J., Woodward E„ 1985):

- NPS;

- diaphragmatic-esophageal ligament;

- mucous “rosette”;

- acute angle of His;

- intra-abdominal location of the LES;

- circular muscle fibers of the stomach.

The main role in the “obturator” mechanism of the cardia is given to the state of the LES. In healthy people, the pressure in this zone is 20.810.3 mmHg. Art. In patients with GERD, this indicator decreases to 8.9±2.3 mmHg. Art. (Dodds W. et al., 1982). The tone of the LES is influenced by a significant number of exogenous and endogenous factors. Pressure in the LES decreases under the influence of a number of gastrointestinal hormones: glucagon, somatostatin, cholecystokinin, secretin, vasoactive intestinal hormone, enkephalins. Some of the widely used medications also have a depressive effect on the obturator function of the cardia: cholinergic substances, sedatives and hypnotics, beta blockers, nitrates, theophylline, etc. The tone of the LES is reduced by eating certain foods: fatty foods, chocolate, citrus fruits, tomatoes , as well as alcohol and smoking. Direct damage to the muscle tissue of the cardiac sphincter (surgical interventions, long-term administration of a nasogastric tube, bougienage of the esophagus, scleroderma) can cause gastroesophageal reflux. Often retrograde entry of gastric or duodenal contents into the esophagus is observed in patients with hiatal hernia. Reflux due to hiatal hernia is due to a number of reasons:

- dystopia of the stomach into the chest cavity leads to the disappearance of the angle of His and disruption of the valve mechanism of the cardia (Gubarev valve);

- the presence of a hernia neutralizes the locking effect of the diaphragmatic crura in relation to the cardia;

- the localization of the lower esophageal sphincter in the abdominal cavity suggests the influence of positive intra-abdominal pressure on it, which significantly potentiates the obturator mechanism of the cardia. Hiatal hernia is a fairly common cause of GERD, according to W. Wienbeck and j. Bamert (1989), hiatal hernia is found in 50% of subjects over the age of 50 years and in 63-84% of them signs of reflux esophagitis are endoscopically determined.

II. The role of reflux of gastric and duodenal contents in GERD.

There is a positive relationship between the likelihood of reflux esophagitis and the level of acidification of the esophagus (Stanciu S., 1975; Gotley D. et al., 1991). Animal studies have clearly demonstrated the damaging effects of hydrogen ions and pepsin, as well as bile acids and trypsin, on the protective mucosal barrier of the esophagus. At the same time, almost all researchers recognize the role not of absolute indicators of aggressive components of gastric and duodenal contents entering the esophagus, but of the duration of the delay (decreased clearance) and resistance of the esophageal mucosa.

III. Clearance and resistance of the esophageal mucosa.

The esophagus is equipped with a very effective mechanism that allows one to eliminate shifts in intraesophageal pH towards an acidic environment. This protective mechanism is called esophageal clearance, which is defined as the rate of release of a chemical irritant from the esophageal cavity. Esophageal clearance is ensured due to active peristalsis of the organ, as well as the alkalizing component of saliva and mucus. With GERD, there is a slowdown in esophageal clearance, associated primarily with weakened esophageal peristalsis and dysfunction of the antireflux barrier (De Meo M, Sontag S, 1992). Resistance of the esophageal mucosa is caused by preepithelial, epithelial and postepithelial factors. Epithelial damage begins when hydrogen ions and pepsin or bile acids overcome the aqueous layer that bathes the mucosa, the preepithelial protective layer of mucus and active bicarbonate secretion. Cellular resistance to hydrogen ions depends on the normal level of intracellular pH (7.3 - 7.4). Necrosis occurs when this mechanism exhausts itself. Increased cell turnover due to increased proliferation of basal cells of the esophageal mucosa counteracts the formation of small superficial ulcerations. The postepithelial effective protective mechanism against acid aggression is the blood supply to the mucosa.

Clinic and diagnostics

The first stage of diagnosis is interviewing the patient. Among the symptoms of GERD, the main ones are heartburn, sour belching, a burning sensation in the epigastrium and behind the sternum, which often occur after eating, when bending the body forward or at night. The second most common symptom of this disease is retrosternal pain. The pain radiates to the interscapular region, neck, lower jaw, left half of the chest and can simulate angina. For differential diagnosis of the genesis of pain, it is important what provokes and relieves pain. Esophageal pain is characterized by its connection with food, body position and relief by taking alkaline mineral waters and soda. Extraesophageal manifestations of the disease include pulmonary (cough, shortness of breath, most often occurring in a lying position), otolaryngological (hoarseness, drooling) and gastric (rapid satiety, bloating, nausea, vomiting) symptoms. Various methods are used to detect gastroesophageal reflux. When X-raying the esophagus, it is possible to record the penetration of contrast from the stomach into the esophagus and detect a hiatal hernia. A more reliable method for detecting gastroesophageal reflux is long-term pH-metry of the esophagus, which allows assessing the frequency, duration and severity of reflux. In recent years, scintigraphy of the esophagus with a radioactive isotope of technetium has been used to assess esophageal clearance. A delay of the ingested isotope in the esophagus for more than 10 minutes indicates a slowdown in esophageal clearance. The study of daily pH and esophageal clearance allows us to identify cases of reflux before the development of esophagitis. The main method for diagnosing GERD is endoscopic. Endoscopy can confirm the presence of reflux esophagitis and assess its severity. In accordance with the endoscopic classification of Savary and Miller, 4 degrees of esophagitis are distinguished:

I degree - isolated non-confluent erosions and/or erythema of the distal esophagus;

II degree - erosive lesions that merge, but do not cover the entire surface of the mucous membrane;

III degree - ulcerative lesions of the lower third of the esophagus, merging and covering the entire surface of the mucosa;

IV degree - chronic ulcer of the esophagus, stenosis, Barrett's esophagus (cylindrical metaplasia of the esophageal mucosa).

Complications of reflux esophagitis.

Peptic ulcers of the esophagus are observed in 2-7% of patients with GERD, in 15% of them they are complicated by perforation, most often into the mediastinum. Acute and chronic blood loss of varying degrees is observed in almost all patients with peptic ulcers of the esophagus, and in half of them it is severe. Stenosis of the esophagus makes the disease more persistent: dysphagia progresses, health worsens, and body weight decreases. Esophageal strictures occur in approximately 10% of patients with GERD. Clinical symptoms of stenosis (dysphagia) appear when the lumen of the esophagus narrows to 2 cm. Barrett's esophagus is a serious complication of GERD, since this sharply increases (30-40 times) the risk of developing cancer. Against the background of cylindrical metaplasia of the epithelium, peptic ulcers often form and strictures of the esophagus develop. Barrett's esophagus is detected by endoscopy in 8 - 20% of patients with GERD (Levin D., 1992). Clinically, Barrett's esophagus is manifested by general symptoms of reflux esophagitis and its complications. The diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus must be confirmed histologically (detection of columnar rather than stratified squamous epithelium in biopsies).

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, treat esophagitis, and prevent or eliminate complications. Treatment of GERD can be conservative or surgical.

Conservative treatment

Conservative treatment includes:

- Recommendation to the patient of a certain lifestyle and diet;

- taking antacids and alginic acid derivatives;

- antisecretory drugs (histamine H2 receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors);

- prokinetics that normalize motility (activation of peristalsis, increased activity of the LES, acceleration of gastric emptying).

1 . General recommendations on regimen and diet.

Basic rules that the patient must follow:

- after eating, avoid bending forward and not lying down; sleep with your head elevated;

- do not wear tight clothes and tight belts;

- avoid large meals;

- do not eat at night;

- limit the consumption of foods that cause a decrease in LES pressure and have an irritating effect (fats, alcohol, coffee, chocolate, citrus fruits);

- stop smoking; avoid accumulation of excess body weight; Avoid taking medications that cause reflux (anticholinergics, sedatives and tranquilizers, calcium channel inhibitors, beta blockers, theophylline, prostaglandins, nitrates).

2. Antacids and alginates.

Antacid therapy aims to reduce the acid-proteolytic aggression of gastric juice. By increasing intragastric pH, these drugs eliminate the pathogenic effects of hydrochloric acid and pepsin on the esophageal mucosa. Currently, alkalizing agents are produced, as a rule, in the form of complex preparations; they are based on aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide or bicarbonate, i.e., non-absorbable antacids (phosphalugel, Maalox, Magalfil, etc.). The most convenient pharmaceutical form for GERD is gels. Usually the drugs are taken 3 times a day, 40-60 minutes after meals, when heartburn and retrosternal pain most often occur, and at night. It is also recommended to adhere to the following rule: every attack of pain and heartburn should be stopped, since these symptoms indicate progressive damage to the esophageal mucosa. Preparations containing alginic acid have proven themselves well in the treatment of reflux esophagitis. These drugs include Topalcan (Topaal), produced (France), which, along with aluminum hydroxide and magnesium carbonate, contains alginic acid. Alginic acid forms a foamy antacid suspension that floats on the surface of the gastric contents and enters the esophagus in case of gastroesophageal reflux, providing a therapeutic effect. According to our data, for grade 1 reflux esophagitis, topalcan can be used as monotherapy; for grade 2–3 reflux esophagitis, antisecretory drugs should be added to topalcan.

3. Antisecretory drugs.

The goal of antisecretory therapy for GERD is to reduce the damaging effect of acidic gastric contents on the esophageal mucosa during gastroesophageal reflux. The most widely used drugs for reflux esophagitis are histamine H2 receptor blockers (ranitidine, famotidine). Numerous clinical trials of H2 receptor blockers have shown that after 8 weeks of treatment, healing of defects in the esophageal mucosa occurs in 65 - 75% of patients. We used Kvamatel (famotidine), manufactured (Hungary), in 27 patients with grade I-II reflux esophagitis associated with duodenal ulcer; in all cases, we obtained good results with 4-6 weeks of treatment. In recent years, fundamentally new antisecretory drugs have appeared - H+, K+ - ATPase blockers (omeprazole, lansoprazole, pantoprazole). By inhibiting the proton pump, they provide a pronounced and long-lasting suppression of acidic gastric secretion. Proton pump inhibitors are especially effective in peptic erosive-ulcerative esophagitis, providing scarring of the affected areas in 90-96% of cases after 4-5 weeks of treatment. However, antisecretory drugs, while promoting the healing of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the esophagus, do not eliminate reflux as such.

4. Prokinetics.

Prokinetics have an antireflux effect. One of the first drugs in this group was the central dopamine receptor blocker metoclopramide (cerucal, raglan). Metoclopramide enhances the release of acetylcholine in the gastrointestinal tract (stimulates the motility of the stomach, small intestine and esophagus), blocks central dopamine receptors (impact on the vomiting center and the center for regulating gastrointestinal motility). Metoclopramide increases the tone of the LES, accelerates gastric emptying, has a positive effect on esophageal clearance and reduces gastroesophageal reflux. The disadvantages of metoclopramide include its undesirable central effects (headache, insomnia, weakness, impotence, gynecomastia, increased extrapyramidal disorders). Recently, instead of metoclopramide, motilium (domperidone), which is an antagonist of peripheral dopamine receptors, has been successfully used for reflux esophagitis. The effectiveness of motilium as a prokinetic agent does not exceed that of metoclopramide, but the drug does not cross the blood-brain barrier and has virtually no side effects. Motilium is produced, it is prescribed 1 tablet (10 mg) 3 times a day 15 - 20 minutes before meals. We have obtained a positive result of monotherapy with Motilium in patients with 1 - 2 degrees of esophagitis. With grade III reflux esophagitis, there is a need to prescribe antisecretory drugs (famotidine, omeprazole). A promising drug for the treatment of reflux esophagitis is prepulsid (cisapride), a gastrointestinal prokinetic agent. It lacks antidopaminergic properties; its action is based on an indirect cholinergic effect on the neuromuscular apparatus of the gastrointestinal tract. Prepulsid increases the tone of the LES, increases the amplitude of contractions of the esophagus and accelerates the evacuation of gastric contents. At the same time, the drug does not affect gastric secretion, so it is better to combine prepulsid with reflux esophagitis with antisecretory drugs. In case of reflux esophagitis caused by reflux of duodenal contents (primarily bile acids) into the esophagus, which is usually observed in gallstone disease, a good effect is achieved by taking non-toxic ursodeoxycholic bile acid (ursofalk), which in this case is advisable to combine with prepulsid.

Surgery

The goal of operations aimed at eliminating reflux is to restore normal function of the cardia. Indications for surgical treatment: 1) failure of conservative treatment; 2) complications of GERD (strictures, recurrent bleeding); 3) frequent aspiration pneumonia; 4) Barrett's esophagus (due to the risk of malignancy). Especially often, indications for surgery arise when GERD is combined with a hiatal hernia. The main type of surgery for reflux esophagitis is Nissen fundoplication. Currently, laparoscopic fundoplication methods are being developed and implemented.

Choice of treatment method

The choice of treatment method is related to the course and cause of GERD. G. Tytgat, conducting a round table discussion on “Gastroduodenal reflux disease” at the First Joint Gastroenterological Week in Athens (1992), recommended adhering to the following rules:

- mild disease (grade 0-1 reflux esophagitis) requires a special lifestyle and, if necessary, taking antacids or H2 receptor ;

- with moderate severity (grade II reflux esophagitis), along with constant adherence to a special lifestyle and diet, long-term use of H2 receptor blockers in combination with prokinetics or proton pump inhibitors is necessary;

- in case of severe illness (grade III reflux esophagitis), a combination of H2 receptor blockers and proton pump inhibitors or high doses of H2 receptor blockers and prokinetics are prescribed;

- the lack of effect of conservative treatment or complicated forms of reflux esophagitis are an indication for surgical treatment.