- home

- general surgery

- Stomach and duodenal ulcers

For benign and malignant diseases of the stomach and duodenum, in most cases, surgical intervention can be performed laparoscopically with good clinical effect. At the same time, endoscopic operations on the organs of the upper abdominal cavity are distinguished by their delicacy and functionality, and should be performed by a surgeon with sufficient experience in open classical surgery. The enlarged image on the monitor allows you to perfectly visualize all the finest anatomical formations in this area - the vagus nerve, gastric vessels and fascial spaces for gentle surgery.

You can read articles and watch videos about the operations performed:

National Television and Radio Company of Uzbekistan. News. Master class by K.V. Puchkova SurgutInformTV. STV Results of the week SurgutInformTV. STV News of Surgut from 06/03/09 Medical Newspaper. Traditional meeting place

Peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum

In case of peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum, indications for surgical treatment arise in complicated forms (stenosis, perforation, malignancy, bleeding). With the modern development of pharmacology, drug therapy for peptic ulcer disease has practically solved all problems. However, there remain a number of patients resistant to the prescribed therapy, and even complex treatment, including physiotherapy and sanatorium treatment, does not relieve patients from frequent relapses. In such cases, indications for surgical treatment arise.

In my practice, in case of duodenal ulcer, I strive to perform organ-preserving operations - these are various types of selective vagotomies (intersection of the branches of the vagus nerve responsible for the excessive secretion of hydrochloric acid), which allows the patient to be cured of a peptic ulcer, but at the same time preserve the stomach. In the presence of stenosis, pyloroplasty (elimination of the narrowed area in the outlet of the stomach) or gastrodudenostomy bypass, which works as the stomach’s own pyloric valve, is additionally performed. When isolating the esophagus and stomach, I use a modern device for dosed electrothermal tissue ligation “LigaSure” (USA), which makes it possible, without damaging the surrounding structures, to “seal” the vessels without leaving surgical clips and suture threads in the abdomen.

For gastric ulcers (caleptic ulcer, penetrating, stenosis, malignancy), I perform laparoscopic distal gastrectomy with the formation of anastomoses using endoscopic staplers (Switzerland, USA).

I have developed an original method for suturing the gastric stump during its resection, which provides more reliable results of surgical treatment, and received an author's certificate for the method of operation I proposed.

Certificate of authorship. Method of suturing the gastric stump

My personal experience includes more than 200 laparoscopic operations for gastric and duodenal ulcers and is summarized in more than 40 scientific publications in various professional peer-reviewed scientific publications in Russia and abroad. I have written two monographs on this topic, based on an analysis of the results of my work: “Technology of dosed ligating electrothermal effects at the stages of laparoscopic operations” and “Simultaneous laparoscopic surgical interventions in surgery and gynecology.”

My seminars on laparoscopic treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers and other diseases of the abdominal organs are attended by medical specialists from major scientific centers, republican, regional and regional hospitals, and students of postgraduate education faculties.

After laparoscopic operations, 3–4 incisions 5–10 mm long remain on the skin of the abdomen. From the first day, patients begin to get out of bed, drink, and from the second day - take liquid food. Discharge from the hospital is carried out on 3-4 days. The patient can begin work in 2–3 weeks. After surgery, a strict diet is required for 2 months, then a lighter diet for six months. They usually return to normal eating after a few months.

At the request of patients, in the clinic before surgery, they can undergo a full examination to determine the optimal treatment tactics and choose the method of surgical intervention.

Causes of peptic ulcer

- The presence of Helicobacter pylori in the stomach and duodenum, which is the main etiological factor in the occurrence of ulcers. The influence of other bacteria has not been proven

- Eating disorder

- Alcohol and tobacco abuse

- Long-term use of drugs that affect the gastric mucosa, the main ones: NSAIDs and glucocorticosteroids (prednisolone)

- Emotional overstrain, stress

- Genetic predisposition

- Metabolic disorders

- Hypovitaminosis

Frequently asked questions by patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers

Is it necessary to somehow prepare for laparoscopic treatment of a stomach ulcer?

If you are planning surgical treatment of a gastric and duodenal ulcer, I ask you to carefully study the preoperative preparation section.

What technologies do you use during your operations?

Among the minimally invasive surgery technologies I use are electrosurgery using the LigaSure device (USA) to reduce the volume of blood loss and gentle surgery, ultrasonic scissors, modern stitching devices for the most delicate connection of the stomach wall, synthetic absorbable suture material, anti-adhesion barriers and liquid media for prevention adhesive disease after surgery, compression hosiery for the prevention of thrombosis and pulmonary embolism, and a number of other techniques that can significantly improve the speed, quality and efficiency of the operations I perform.

What anesthesia do you use for laparoscopic treatment of gastric ulcers?

If you would like to learn in more detail about the methods of pain relief used in the surgical treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers, please read carefully the information specifically posted on the website.

Is it possible to simultaneously perform laparoscopic surgery for a stomach ulcer and, for example, cholelithiasis?

The methods of high-tech minimally invasive surgery that I use make it possible to perform two and sometimes three operations simultaneously during one anesthesia by a team of several surgeons. The issue of simultaneous operations, including for stomach ulcers in combination with cholelithiasis, is discussed in more detail in a special section of the site. Simultaneous performance of several surgical interventions will reduce the load on the body, reduce hospitalization time, and speed up the body’s recovery compared to performing several operations with an interval of 5-6 weeks.

Where can I have surgery for a stomach ulcer?

I conduct the initial consultation with all patients in Moscow at the Swiss University Clinic, where there is a modern surgical facility capable of solving any operational problems.

Useful links to various sections of the site when preparing for surgery to treat liver cysts:

preparation for laparoscopic surgery for gastric and duodenal ulcers ... pain relief during surgery for gastric and duodenal ulcers ... simultaneous (simultaneous) operations for gastric and duodenal ulcers ... reviews of operated patients with gastric and duodenal ulcers ... scientific publications on the treatment of gastric ulcers and duodenum

Diagnostics

- General clinical analysis of blood and urine

- Analysis of stool for coprogram

- Fecal occult blood test

- Biochemical blood test (liver tests, cholesterol, alkaline phosphatase)

- ECG

- X-ray of the chest organs in 2 projections and X-ray of the abdominal organs (to exclude perforation of ulcers)

- X-ray of the esophagus, stomach with barium mixture

- Ultrasound of the hepatobiliary system

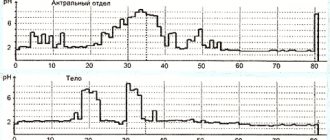

- 24-hour pH monitoring in the lower esophagus and stomach

- EGDS

- Non-invasive tests for the determination of Helicobacter pylori (respiratory)

4.Treatment

Perforation of an ulcer is an absolute and unambiguous indication for emergency surgery. The techniques used (suturing, resection, etc.), antiseptic measures, postoperative treatment and rehabilitation strategies may be different, since the characteristics of a perforated ulcer vary widely and, in addition, the scale and stage of the process at the time of intervention is of key importance.

An important task is the prevention of complications - pneumonia, purulent inflammation, peristalsis disorders, etc.

It remains to add that even the constant skill of the domestic school of emergency surgery (and only the surgeons themselves truly know that in order to save a patient’s life in the operating room, only the surgeons themselves truly know), a perforated ulcer is characterized by a significant mortality rate (today this is 6-8%). The prognosis depends critically on the timeliness of seeking help and its provision, on the accuracy of diagnosis and the choice of the optimal surgical plan.

Signs of a perforated stomach ulcer

Acute abdominal pain may be a sign of a peptic ulcer.

In the typical form of an ulcer, fluid from the stomach enters the abdominal cavity. Three main stages of development:

- Stage of development of chemical peritonitis. The course is very short in duration - from 3 to 6 hours. Directly depends on the size of the hole and the amount of discharge into the abdominal cavity. During this period, acute pain in the stomach progresses. Unbearable pain appears in the peri-umbilical area, radiating to the right hypochondrium. After some time, pain covers the entire abdominal area. Perforation of the stomach wall is sometimes manifested by pain in the left abdomen. Painful sensations vary in duration. In rare cases, vomiting is possible. There are no changes in heart rate, but blood pressure is reduced. Breathing increases significantly. With increased sweating, the skin turns pale. Due to the fact that gases accumulate in the abdominal cavity, all the muscles of the anterior abdominal region are tense.

- Stage of bacterial peritonitis. The period begins to progress 6 hours after perforation. Tension subsides from the abdominal muscles, breathing normalizes and acute pain disappears. The patient feels complete relief. At this stage, sharp jumps in temperature appear, the pulse quickens, and blood pressure continues to fluctuate. The stage of increasing intoxication begins, which leads to an increase in gas formation and paralysis of peristalsis. Characterized by a dry tongue and the formation of a gray coating throughout the entire oral cavity. The patient's behavior changes regularly. He may experience joy and relief, be careless about his condition, and protect himself from various troubling situations. If emergency medical care is not provided at the stage of increased toxicity, the patient will be on a straight path to the third, most dangerous phase of the disease.

- Stage of acute intoxication. The process usually takes effect after a 12-hour period, counting from the moment of illness. The main manifestation is constant vomiting, which removes water from the body. Transformations of the skin can be noted visually. The skin becomes dry. The body continues to suffer from sharp changes in body temperature. The temperature ranges from a normal value of 36.6° to a critical value of 40°. The pulse is on the border of 120 beats per minute. Upper blood pressure drops to 100 mmHg. The patient is overcome by lethargy, indifference, and a slow reaction to any allergens. The abdomen grows in volume due to free gases and liquids that accumulate in the cavity. Problems with urination appear until it stops completely. The only outcome for the patient at this stage of peritonitis is death. It is no longer possible to save a life.

1.General information

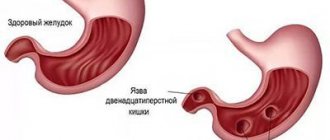

An ulcer is a long-term non-healing inflamed wound surface on the epidermal (external, skin) or mucous membrane. It should be immediately clarified that the concepts “ulcer” and “erosion”, often confused and even used as synonyms, are not the same thing. Unlike erosion or a superficial scratch, an ulcer penetrates into the deep, base layers of the corroded surface, which leads to the irreversible loss of one or another volume of tissue, and consequently to losses in its functionality. Healing of ulcers occurs by partial or complete replacement of the defect with connective tissue (“healed ulcer”).

The old Russian verb “pierce” means to make a hole, break through, pierce, pierce; The Latin word “perforate” has the same meaning, which has many derivatives both in the world of technology and in medicine.

Thus, a perforated (perforated) ulcer is an ulcer through and through, an ulcer with a violation of the tightness and the formation of a “hole”. The term “perforated ulcer” is used only in gastroenterology and implies an aggressive ulcer of the stomach or duodenum - as their walls become thinner, they can eventually break through; in every tenth case, the effusion of contents into the abdominal cavity is also accompanied by massive bleeding. In general, perforation of a gastroduodenal ulcer is one of the most dangerous and severe outcomes of peptic ulcer disease, creating an immediate threat to the patient’s life.

Considering the prevalence of ulcerative-inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (several million people suffer from them in Russia alone), there is no need to talk for long about the severity and relevance of the problem of perforated ulcers. Today, one of the main tasks of gastroenterology remains the development not so much of diagnostic and emergency surgical protocols (see below), but of methods for accurately assessing the type of course and dynamics of peptic ulcer disease, as well as reliable prediction and reliable prevention of its perforated variants.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Treatment of perforated gastric ulcer

Surgical intervention is a method of treating perforated ulcers.

The treatment method for perforated ulcers is surgery. The course of preoperative preparation includes the removal of intestinal contents and stabilization of blood pressure.

Diagnostics are also necessary to draw up a plan for further action. Need to evaluate:

- Stage of the disease according to the time elapsed since the onset of the disease;

- The nature of origin, location and volume of the ulcer;

- The level of development of peritonitis and the extent of its spread throughout the body;

- Age range of the patient;

- The presence or absence of parallel deviations;

- The technical side of the inpatient department and the level of competence of doctors.

According to statistics, deaths after surgery are quite twofold. After 6 hours, about 4% of ulcer patients die, after 24 hours - up to 40%.

The main conditions of the diet:

- The number of meals during the day is 6 times. Portions must be small.

- All food taken must be brought to a puree-like state, or semi-liquid.

- It is better to cook food in a double boiler or simply boil it.

- Minimize the amount of salt consumed.

- You also need to remove carbohydrates (sugar, chocolate, flour) and liquids from your diet.

- 2 days after the operation, you are allowed to drink mineral water, fruit cocktails, and weak, slightly sweetened teas.

- At the end of 2-3 days, you can add rosehip decoction, pureed soups and porridges made from rice and buckwheat to the diet. You can eat, within reason, vegetable puree soups made from boiled pumpkin, zucchini, potatoes or beets. If you have enough enthusiasm, you can make a soufflé based on pureed cottage cheese.

- Bread products (crackers, bread, dry goods) should not be included in the diet earlier than a month after surgery.

Key points

- Ulcer perforation is associated with a short-term mortality rate of up to 30% and is considered one of the most dangerous surgical emergencies worldwide.

- Incidence has remained constant in developed countries in recent decades, but with significant geographic differences in other regions such as Africa and Asia

- Helicobacter pylori, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and smoking are established risk factors for ulcers, but the pathogenesis leading to perforation is not well known.

- Clinical prediction rules can identify patients at high risk of death, but with variable accuracy

- Elderly patients with sepsis have the highest mortality rates when surgery is delayed

- Surgical treatment should not be delayed in patients with widespread peritonitis, because every hour of delay increases the risk of death

- Laparoscopic surgery has similar morbidity and mortality compared to open surgery

- Patients with clinical signs of spontaneous resolution of ulcers can be treated conservatively in selected cases

- New techniques, including endoscopic ones, may reduce surgical damage and improve outcomes in the future.

- Further improvement should be achieved by expanding the selection of patients for surgical intervention, as well as alternative strategies and improving the preoperative management of septic patients

Introduction

Perforated ulcer is a surgical emergency and is associated with short-term mortality of up to 30% of patients and morbidity of up to 50%. Worldwide variations in demographics, socioeconomic status, Helicobacter pylori prevalence, and prescription medications make it difficult to identify risk factors for perforated ulcers. A complication of peptic ulcer perforation manifests itself in the form of acute abdominal syndrome with localized or widespread peritonitis, as well as a high risk of sepsis and death. Early diagnosis is important, but clinical signs may be unrecognized in elderly or immunocompromised patients, thereby delaying diagnosis. Imaging methods play an important role in diagnosis, as well as early management of such patients in intensive care settings, including the prescription of antibiotics.

Appropriate risk assessment and selection of therapeutic alternatives become important to address the risk of morbidity and mortality. In this review, we provide an update on the current understanding and management of perforated ulcers.

Epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease and its complications

Complications of peptic ulcer disease include perforation, bleeding and obstruction. Although perforations are the second most common complication after bleeding (ratio of about 1:6), they represent the most common indication for emergency surgery for peptic ulcer disease. General advances in patient management have made obstruction due to scarring of recurrent ulcers a rare occurrence, and the use of endoscopic techniques and transarterial embolization has reduced the need for emergency surgery for bleeding ulcers. In 2006, more than 150,000 patients were hospitalized due to complications of peptic ulcers in the United States alone. Although the overall proportion of complications due to perforation (N = 14,500 [9%]) was seven times less than those due to bleeding, perforation accounted for 37% of all ulcer-related deaths. According to data from the USA, more than one out of every ten hospitalizations due to peptic ulcer disease (PU) complicated by perforation ends in the death of the patient.

Indeed, perforation of an ulcer has a mortality rate approximately 5 times higher than that of bleeding from an ulcer, and it was also the most significant factor in mortality in US hospitals according to data from 1993 to 2006, with an odds ratio (OR) of 12.1 (95% confidence level). interval (CI) 9.8-14.9).

Many studies show a steady rate of perforation during the 1980s and 1990s, but studies from Sweden, Spain, and the United States in the 1990s and early 2000s reported a decline in the incidence of both bleeding and perforation. Mortality rates for ulcer perforation in Europe have been fairly stable over the past three to four decades, despite advances in intraoperative care, imaging techniques, and surgical management.

The epidemiology of peptic ulcer disease has generally changed over the past 50 years, initially transformed by changes in socioeconomic development in high-income countries, later by the identification and treatment of H. pylori as the causative agent, and finally by the introduction of proton pump inhibitors. , from 1989 until now. In low- and middle-income countries during this period, the average age at diagnosis increased by more than two decades (from 30–40 years to 60 years and older), the gender distribution leveled off (the male to female ratio changed from 4 -5:1 to almost 1:1), and the previously predominant location of the ulcer in the duodenum now shifts to the more common gastric ulcer. Geographic differences also exist in the causes and variations in risk factors for perforated ulcers.

Regional differences exist even within Europe, such as between Turkey and Belarus, which differ in socioeconomic development, prevalence of H. Pylori, and smoking habits, which increase the incidence of peptic ulcer perforation. It is noteworthy that the occurrence of peptic ulcer disease in low- and middle-income countries, where its incidence is several times higher than in high-income countries (Figure 1), follows a distribution similar to the patterns described for developed countries in the mid-20th century . For example, African cohorts from Nigeria, Kenya, Ethiopia, Tanzania, and Ghana report an incidence of peptic ulcers in male patients that is 6 to 13 times higher than in women, a mean age of approximately 40 years, and a predominant localization of ulcers in the duodenum. intestine in approximately 90% of patients. Similar trends are observed in the Middle East, Arab countries and parts of southern Asia.

Pathogenesis, causes and risk factors for ulcer perforation

Although the general imbalance between protective and ulcerogenic factors in the formation of peptic ulcer disease is obvious, the reasons for the complication of perforation in some patients do not remain unclear. Ulcerogenesis is promoted by infection (H. pylori), disruption of the barrier properties of the mucosa (for example, taking medications), as well as an increase in the production of hydrochloric acid (panel, Figure 2). However, precise risk estimates and the individual impact of each factor are still poorly understood. Only about a third of patients with perforated ulcers had or have a history of peptic ulcers at the time of diagnosis of perforation. In addition, some patients develop very small (<5 mm) perforations without large mucosal defects, suggesting that ulcer size is not associated with perforation risk, while others may develop large mucosal defects with perforations as large as a few centimeters. On the other hand, the putative pathogenesis and role of H. pylori virulence factors is widely considered. The gastric mucosa of about 50% of the world's population is colonized by H. pylori, but it causes disease in only 10-20%. H. pylori has a variable prevalence (0-90%) in perforated ulcers and can develop in the absence of Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Of note are co-factors such as smoking and alcohol, reported in different studies from different regions (Figure 2).

The incidence of perforation partially follows the geographic distribution of H. pylori, with duodenal perforation being more common in regions where H. pylori is the primary cause. One study found an increased incidence of H. pylori in regions with a high incidence of perforation, suggesting a potential dose-dependence leading to this complication. The virulence of H. pylori may also contribute because different strains appear to have different pathogenic effects. In addition, ulcer perforation can also occur in children, and in them it is usually associated with H. pylori (in 90% of cases).

In parallel with the decline in the prevalence of H. pylori in many high-income countries (estimated at 20-30%), a shift from duodenal ulcers to gastric ulcers has been reported in elderly patients, due to the increased use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in this population. group of the population. The daily peak of ulcerative perforations has been reported to occur in the first half of the day, possibly due to circadian changes in hydrochloric acid secretion. The risk of perforation increases during fasting periods, such as Ramadan, which may also be explained by changes in acid release and exposure. Ulcerative perforations have also been reported to occur after bariatric surgery, after use of crack cocaine or amphetamine, and after courses of chemotherapy using angiogenesis inhibitors such as bevacizumab. Patients with hypersecretion of hydrochloric acid, including gastrinoma (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome), are at risk of perforation, and therefore gastrinoma should be excluded in patients with multiple or recurrent ulcers.

Fig.1. Population burden of peptic ulcer disease, according to the Human Development Index (HDI) of various countries

Years of life lost and years of life with disability according to HDI quintiles. Assumptions about the correlation of PU with age have been revised thanks to data from the global HDI study. In 2010, mortality proportions (circle size) were analyzed, as well as the number of years of life lost and years of life with disability in both sexes. Data provided by the HDI Quintile Program for United Nations Development.

Clinical assessment and diagnosis

Perforated ulcers in patients often debut with severe, sudden pain in the epigastric region, which can become diffuse. Peritonitis from acid exposure may appear as a hard, plank-shaped abdomen due to muscle tension. The clinical picture may be mild in obese patients, immunocompromised individuals, patients on steroids, individuals with a reduced level of consciousness, the elderly, and children. In such situations, medical history and examination findings may be nonspecific, prompting the use of additional imaging and laboratory tests to establish a differential diagnosis. Only two thirds of patients present with overt signs of peritonitis, which may partly explain the delay in diagnosis in some patients. During the clinical examination, several differential diagnoses should be considered, but the most important thing is to exclude rupture of an abdominal aortic aneurysm or acute pancreatitis, the former because of the high mortality rate if recognition is delayed and treatment is delayed, and the latter because its management is largely conservative.

Fig.2. Mechanisms and factors in the pathogenesis of perforated peptic ulcer

(A) An imbalance between aggressive and protective factors triggers the ulcerogenic process, and (B), although many of its participants are known, it is Helicobacter pylori infection (mainly for duodenal ulcers) and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (mainly for gastric ulcers) , appear to be important in disrupting the protective layer of mucous membranes, exposing the gastric epithelium to acid. (C) Some additional factors (for example, smoking, alcohol consumption, as well as medications and drugs) can enhance the process of ulcerogenesis (D), which leads to erosion (E). Eventually, the serosa is disrupted (F), and when perforated, the digested contents, including acidic fluid, enter the abdominal cavity, causing severe pain as well as local peritonitis, which can become generalized and ultimately lead to systemic inflammatory response syndrome and sepsis with a risk of multiple organ failure and death.

Diagnostic imaging in critically ill patients may have to be delayed until the condition improves. Those admitted with peritonitis, with or without signs of sepsis, should usually be taken directly to the operating room. It should be noted that the risk of death increases with every hour of delay in the operation.

Laboratory markers and radiological imaging

Laboratory markers are not diagnostic criteria for perforated ulcers. However, they help clinicians evaluate the inflammatory response and organ function, and rule out relevant differential diagnoses such as acute pancreatitis. Blood cultures should be obtained before broad-spectrum antibiotics are started, and antibiotic treatment should not be delayed for long. Arterial blood gas measurements can complement clinical assessment of vital signs (eg, pH, lactate, buffer bases, and saturation) and may also measure the degree of metabolic compromise in patients with sepsis.

Gastroduodenal perforation is the most common cause of pneumoperitoneum, along with perforated diverticulitis (in high-income countries) and perforations of typhoid or salmonella etiology (in low- and middle-income countries). Thus, the detection of so-called free gas during a radiological examination is very indicative of perforation of a hollow organ. A standing X-ray of the chest or abdomen in a direct projection is an easy, cheap, quickly performed, and most importantly, an informative diagnostic method. However, its sensitivity is only 75% and it cannot show the exact cause of pneumoperitoneum.

There are reports of the diagnostic use of ultrasound, but the approach is not widely used and is highly dependent on the physician performing the diagnosis. Abdominal CT has become the imaging modality of choice due to its high sensitivity (reportedly 98%) and added value in evaluating other differential diagnoses.