Composition per capsule:

Active substance:

omeprazole pellets – 235 mg, containing omeprazole – 20 mg.

Auxiliary substances included in the pellets:

methacrylic acid and ethyl acrylate copolymer [1:1] (acrylic coating L30D) – 18.90%, calcium carbonate – 2.975%, potassium hydrogen phosphate (dipotassium phosphate) – 1.275%, hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (hypromellose) –

6.25%, mannitol – 17.0%, sugar pellets (sucrose) – 8.0%, sugar syrup (sucrose) – 30.25%, polyethylene glycol 6000 – 2.45%, povidone-K30 (polyvinylpyrrolidone K 30) – 0.075%, sodium hydroxide – 0.125%, sodium lauryl sulfate – 0.45%, talc – 2.45%, titanium dioxide – 0.80%, polysorbate-80 (Tween 80) – 0.50%.

Capsule shell (body):

gelatin up to 100%, water 14-15%;

(lid):

gelatin up to 100%, water – 14-15%, crimson dye (Ponceau 4R) – 0.6666%, quinoline yellow dye – 0.1000%, patent blue dye – 0.0200%, titanium dioxide – 1 .2999%.

Description:

hard gelatin capsules No. 2 with a transparent body and a brown cap, containing white or almost white spherical pellets (granules).

Pharmacotherapeutic group:

a drug that reduces the secretion of gastric glands - a proton pump inhibitor.

ATX code:

A02BC01.

Pharmacological properties

Pharmacodynamics

Inhibits the enzyme H+K+ATPase (“proton pump”) in the parietal cells of the stomach and thereby blocks the final stage of hydrochloric acid synthesis. This leads to a decrease in the level of basal and stimulated secretion, regardless of the nature of the stimulus. After a single dose of the drug orally, the effect of omeprazole occurs within the first hour and continues for 24 hours, the maximum effect is achieved after 2 hours. After stopping the drug, secretory activity is completely restored after 3–5 days. Due to a decrease in the secretion of hydrochloric acid, the concentration of chromogranin A (CgA) increases. Increased concentrations of CgA in blood plasma may affect the results of examinations to detect neuroendocrine tumors.

Pharmacokinetics

Distribution

Omeprazole is absorbed in the small intestine, usually within 3-6 hours. Bioavailability after oral administration is approximately 60%. Food intake does not affect the bioavailability of omeprazole.

The binding rate of omeprazole to plasma proteins is about 95%, the volume of distribution is 0.3 l/kg.

Metabolism

Omeprazole is completely metabolized in the liver. The main enzymes involved in the metabolic process are CYP2C19 and CYP3A4. The resulting metabolites - sulfone-, sulfide- and hydroxy-omeprazole do not have a significant effect on the secretion of hydrochloric acid.

The total plasma clearance is 0.3-0.6 l/min. The bioavailability of omeprazole increases by approximately 50% with repeated doses compared to a single dose.

Removal

The half-life is approximately 40 minutes (30-90 minutes). About 80% is excreted as metabolites by the kidneys, and the rest by the intestines.

Special patient groups

There were no significant changes in the bioavailability of omeprazole in elderly patients or patients with impaired renal function. In patients with impaired liver function, there is an increase in the bioavailability of omeprazole and a significant decrease in plasma clearance.

The use of omeprazole 10 mg in the prevention of relapse of reflux esophagitis

193 patients who were asymptomatic and in remission after 4 or 8 weeks of omeprazole treatment were randomized, double-blind, to receive omeprazole 10 mg once daily (n = 60 evaluable) or omeprazole 20 mg once daily per day (n = 68), or placebo (n = 62) for one year or relapse with symptoms. Treatment with omeprazole in both doses was more effective than placebo in preventing symptomatic relapse (p < 0.001) and endoscopically verified relapse (p < 0.001). After 12 months, the endoscopic remission rate was 50% with omeprazole 10 mg once daily, 74% with omeprazole 20 mg once daily, and 14% with placebo. After 12 months, the rate of symptomatic remission was: 77% with omeprazole 10 mg once daily, 83% with omeprazole 20 mg once daily, and 34% with placebo. The use of omeprazole in both doses (10 and 20 mg) once a day effectively increased the duration of remission of reflux esophagitis. A dose of 10 mg may be the initial therapeutic dose. The presence of a dose-response relationship suggests that a dose of 20 mg once daily may be effective in patients for whom a dose of 10 mg is suboptimal.

Omeprazole 20 mg once daily is an effective drug used in the long-term treatment of reflux esophagitis.1,2 Rational treatment should be accompanied by minimal drug exposure while ensuring maximum effectiveness for the majority of patients3. Therefore, prerequisites arose for studying the use of omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once a day in order to prevent the development of relapse of reflux esophagitis in comparison with the standard dose (20 mg). Preliminary short-term (6-month) studies of omeprazole 10 mg have been performed, the results of which suggest that the drug may be effective as a preventive agent for recurrent reflux esophagitis, although the assessment of its effectiveness was based solely on endoscopic criteria4-5.

This study examined whether omeprazole 10 mg once daily was effective in the long-term treatment of reflux esophagitis (over one year) compared with omeprazole 20 mg once daily and placebo in terms of endoscopic recurrence and relapse with symptoms.

Methods

Study design

193 patients took part in the study. All of them had previously achieved healing of reflux esophagitis and disappearance of symptoms of the disease during therapy with omeprazole 20 mg once daily for 4 to 8 weeks. Patients were randomized, double-blind, to receive omeprazole 10 mg once daily, omeprazole 20 mg once daily, or placebo for one year. Endoscopic examination was carried out 3 months after completion of treatment and when symptoms of relapse occurred.

| Omeprazole 10 mg | Omeprazole 2 0 mg | Placebo | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Patients (n) | 60 | 68 | 62 |

| Gender (men: women) | 44:16 | 48:20 | 48:14 |

| Age (g) | 53 (15) | 53 (14) | 53 (15) |

| Body weight (kg) | 78 (13) | 76 (14) (n=67) | 80 (11) (n=61) |

| Height (cm) | 170 (11) (n=59) | 171 (9) (n=67) | 172 (8) |

| Smokers (%) | 25 | 22 | 19 |

| Drinkers (%) | 67 | 71 | 86 |

| History of esophagitis | |||

| Years since first diagnosis of esophagitis | 1 • 2 (2 • 6) (n = 52) | 1 • 7 (4 • 3) (n = 55) | 1 • 2 (2 • 3) (n = 56) |

| History of symptoms | |||

| Assessment immediately prior to most recent treatment aimed at healing esophagitis | |||

| Heartburn (%) | 98 | 94 | 95 |

| Regurgitation (%) | 77 | 72 | 71 |

| Dysphagia (%) | 37 | 35 | 32 |

| Odynophagia (%) | 25 | 27 | 29 |

| Treatment regimen aimed at healing of esophagitis in the most recent episode* | |||

| Omeprazole 20 mg (%) | 73 | 59 | 60 |

| Omeprazole 20/20 mg (%) | 8 | 13 | 16 |

| Omeprazole 20/40 mg (%) | 18 | 28 | 24 |

Data are presented as numbers or the number of patients in each category or as the mean (standard deviation). *Patients received omeprazole 20 mg once daily for 4 weeks. Patients who were not cured and asymptomatic after 4 weeks received omeprazole 20 mg once daily (omeprazole 20/20 mg) or omeprazole 40 mg once daily (omeprazole 20/40 mg) for subsequent 4 weeks (5-8 weeks).

During patient visits to the clinic (every 3 months), symptoms were recorded: (general health, heartburn, regurgitation, dysphagia), which were assessed on a 4-point scale (0 = no symptoms, 1 = mild symptoms, 2 = moderate symptoms , 3 = severe symptoms).

During the first three months of the study, patients filled out a daily diary recording the severity of symptoms occurring day and night and the number of pills taken. The primary endpoint for diary data was 24-hour symptom freedom. Endoscopic recurrence was defined as recurrence of grade 2–4 esophagitis ( see Table 2 ). Detection of grade 2-4 esophagitis by endoscopic examination in the absence of symptoms or the presence of mild symptoms was considered an asymptomatic relapse. Symptomatic relapse was defined as recurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease with moderate to severe symptoms.

Patients

The main criteria for inclusion of patients in the study were: age 18-80 years, presence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease for at least three months, and grade 2-4 reflux esophagitis confirmed by endoscopic examination ( Table 2 ). The main exclusion criteria were: esophageal varices or esophageal stricture, upper gastrointestinal bleeding, septic ulcer, history of gastrointestinal surgery or vagotomy.

| Omeprazole 10 mg | Omeprazole 20 mg | Placebo | |

| Patients (n) with esophagitis of each severity level | |||

| 0 degree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1st degree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2nd degree (%) | 43 (72) | 44 (65) | 42 (68) |

| 3rd degree (%) | 14 (230) | 22 (32) | 15 (24) |

| 4 degree (%) | 3 (5) | 2 (3) | 5 (8) |

| Linear extent of esophagitis (cm) | 4 • 5 (2 •3)) | 4 • 7 (2 • 1)) (n=67) | 4 •4 (2 • 2)) |

| Strictures traversable with an endoscope used in adults (%) | 4/60 (7) | 8/68 (12) | 4/62 (7) |

| Endoscopic signs of Barrett's esophagus (%) | 5/60 (8) | 1/68 (2) | 5/62 (8) |

Data are presented as numbers or the number of patients in each category or as the mean (standard deviation). Endoscopic severity grades were defined as follows:

- grade - normal mucous membrane.

- degree - macroscopic erosions are not visible; erythema or diffuse redness of the mucous membrane; swelling causing enlargement of folds.

- degree - isolated round or linear erosions, but without completely involving the circle.

- degree - merging erosions involving the entire circle.

- grade - clear benign ulcer.

Barrett's esophagus was defined as the presence of a columnar bordered epithelium extending from more than 3 cm above the proximal edge of the gastric folds (gastroesophageal junction) and around the circumference completely.

At study entry, each patient was confirmed to have healed esophagitis (endoscopy grade 0) and asymptomatic (global evaluation grade 0) after initial treatment with omeprazole. Patients were prematurely excluded from this study if they: (a) had a recurrence of moderate or severe symptoms requiring, in the physician's opinion, the use of a further course of omeprazole therapy; (b) erosive esophagitis (grade 2-4), detected by endoscopic examination after 3 months. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study, which was approved by the ethics committee at each institution.

Statistical analysis

According to the results of the primary analysis, the rate of endoscopic remission after 12 months of treatment with omeprazole 10 mg once daily and placebo was comparable.

Endoscopic and symptomatic remission rates with 95% confidence intervals were determined using life table analysis. In addition to the full analysis of 12 months of data, it was important to analyze the first three months.

Additional comparisons (χ2 tests) of remission rates were performed (all treated patients approach, with denominators 60, 10 mg omeprazole; 68, 20 mg omeprazole, placebo), although it is believed that this analysis may underestimate the true number of patients in remission.

A logistic analysis was performed to identify possible predictors of reduced risk of relapse: covariates included duration of the most recent episode of reflux esophagitis; endoscopic grade of esophagitis or severity of symptoms in general at the time of inclusion in the study.

Graphs were constructed using diary data (percentage of patients reporting symptoms during daytime and nighttime). These data are presented cumulatively as the average number of such days per patient; and comparisons between the two groups were made using the χ2 test. Values are presented as mean standard deviation.

results

193 patients were randomized to treatment with omeprazole 10 mg once daily (n = 61), omeprazole 20 mg once daily (n = 69), or placebo (n = 63). Three patients were lost to follow-up (one in the omeprazole 10 mg group, one in the omeprazole 20 mg group, one in the placebo group) due to missing data on treatment efficacy. These patients were excluded from the analysis. At the time of randomization into the study, there were no significant differences between the groups in demographic characteristics, history of esophagitis, and endoscopic findings ( Tables 1 and 2 ).

Examination during clinical visits

Endoscopic recurrence: one to three months

After 3 months, the rate of endoscopic remission according to the survival probability table (number of patients without grade ≥2 esophagitis, Fig. 1 ) was: 79% (95% confidence interval from 69% to 90%) (68% based on all treated patients) - with using omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once a day; 89% (from 81% to 97%) (76%) - when using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day; 41% (from 28% to 53%) (23%) - using placebo (10 mg group compared with 20 mg group - the difference is not significant; each p < 0.0001 compared with placebo, Fig. 2 ).

At the 3-month clinic visit, fewer patients receiving omeprazole 10 and 20 mg were classified as having asymptomatic endoscopic relapse compared with the placebo group [8 of 47 (17%) patients with symptomatic remission in the omeprazole group 10 mg; 7 out of 58 (12%) - in the omeprazole 20 mg therapy group, the difference between these groups is not significant, each p < 0.001 compared with 18 out of 30 (60%) - in the placebo group]. Of the patients with asymptomatic relapse, 4 of 7 patients received omeprazole 20 mg, and 12 of 18 patients received placebo. There was an association between relapse and mild symptoms.

Endoscopic recurrence: one to 12 months

After 12 months, the rate of endoscopic remission according to the survival probability table was: 50% (95% confidence interval from 34% to 66%) (50% based on all treated patients) - using omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once a day; 74% (from 62% to 86%) (68%) - using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day; and 14% (from 2% to 26%) (10%) when using placebo (10 mg group compared with 20 mg group - the difference is not significant; each p < 0.0001 compared with placebo, Fig. 2 ).

At one year, the number of patients without symptoms but with endoscopic relapse was comparable in both omeprazole treatment groups, although statistical comparison with the placebo group was not possible due to the small number of patients with symptomatic remission in the placebo group [5 of 28 (18%) not had symptoms in the omeprazole therapy group at a dose of 10 mg, 3 out of 39 (8%) in the omeprazole therapy group at a dose of 20 mg, the difference between these groups is not significant; 3 of 5 (60%) in the placebo group]. Of the patients with asymptomatic relapse: 2 of 5 patients received omeprazole 10 mg, 1 of 3 received omeprazole 20 mg, and 1 of 3 received placebo. There was an association between relapse and mild symptoms.

Relapse with symptoms: one to three months

After 3 months, the rate of symptomatic remission according to the survival probability table (the number of patients without symptoms or with mild symptoms, Fig. 3 ) was: 91% (from 84% to 99%) (78% based on all patients treated) - with use omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once a day; 94% (from 88% to 100%) (85%) - when using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day; and 63% (range 55% to 76%) (48%) with placebo (10 mg group versus 20 mg group—not significant; each p < 0.001 versus placebo, Fig. 4 ).

Relapse with symptoms: one to 12 months

At 12 months, the rate of symptomatic remission according to the survival probability table (number of patients without symptoms or with mild symptoms, Fig. 3 ) was: 77% (64% to 89%) (78% based on all patients treated) - with use omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once a day; 83% (from 73% to 93%) (82%) - when using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day; and 34% (16% to 52%) (45%) when using placebo (10 mg group compared with 20 mg group - the difference is not significant; each p < 0.0001 compared with placebo, Fig. 4 ).

Logistic analysis

The determining factors for reducing the likelihood of endoscopic relapse were: treatment (omeprazole 20 mg > omeprazole 10 mg > placebo; p < 0.0001) and the duration of treatment required to achieve endoscopic and symptomatic remission (4 or 8 weeks, p < 0.01); Moreover, the greatest likelihood of achieving stable remission was associated with long-term use of omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day.

Factors that were most predictive of a reduced risk of symptomatic relapse were: treatment (omeprazole 20 mg > omeprazole 10 mg > placebo; P < 0.0001) and overall symptom severity at entry into a previous reflux esophagitis healing study (P < 0.0001). 0.05). At the same time, the greatest likelihood of achieving stable remission was associated with long-term use of omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day, and the presence of mild symptoms with a previous episode of reflux esophagitis.

Survival time in the study

The interval between randomization and premature discontinuation or completion of treatment was longer in the omeprazole treatment groups than in the placebo group (247 days - 10 mg group; 263 days - 20 mg group; the difference between these groups is not significant; each p < 0.001 compared with 113 days in the placebo group).

Symptoms recorded by the doctor

After 3 months, 35 (58%) patients (67% of patients for whom data were available) - when using omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg once daily; 47 [69% (78%)] on omeprazole 20 mg once daily and 17 [27% (42%)] on placebo were completely symptom-free (10 mg group vs. 20 mg group) - the difference is not significant; each p < 0.001 compared to placebo).

The number of patients reporting no symptoms at the end of the study was 32 [53% (56%)] when using omeprazole 10 mg once daily; 46 [68% (71%)] - when using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once a day; 14 [23% (24%)] - when using placebo (10 mg group compared with 20 mg group - the difference is not significant; each p < 0.001 compared with placebo).

In table Figure 3 shows the number of patients who had no specific symptoms after 3 months of treatment and at the end of the study.

| Omeprazole 10 mg | Omeprazole 20 mg | Placebo | |

| Heartburn | |||

| 3 month (%) | 40 (67 (77))† | 51 (75 (85))‡ | 18 (29 (44)) |

| Completion of study (%) | 34 (57 (61))† | 51 (75 (85))‡ | 13 (21 (22)) |

| Regurgitation | |||

| 3 month (%) | 43 (72 (83))* | 56 (82 (93))‡ | 26 (42 (63)) |

| Completion of study (%) | 39 (65 (70))‡ | 55 (81 (85))‡ | 18 (29 (32)) |

| Dysphagia | |||

| 3 month (%) | 48 (80 (94)) | 59 (87 (100))* | 38 (61 (95)) |

| Completion of study (%) | 52 (87 (95)) | 64 (94 (98)) | 50 (81 (86)) |

| Odynophagy | |||

| 3 month (%) | 52 (87 (100))* | 59 (87 (98))* | 40 (65 (98)) |

| Completion of study (%) | 54 (90 (96)) | 60 (88 (92)) | 49 (79 (84)) |

*p < 0.01 † < 0.001 ‡ < 0.0001 compared with placebo; the difference was not significant when compared between the omeprazole 10 and 20 mg treatment groups at each assessment. Data are presented as the number of patients without symptoms. Numbers are presented in parentheses based on: (all patients treated (those patients for which data were available))

Patient diary data assessment: one to three months

Patients treated with omeprazole had a greater number of symptom-free days compared with patients treated with placebo ( Figure 5 ). Cumulatively, after 3 months, each patient had an average of 63 such days in the omeprazole 10 mg group and 65 days in the omeprazole 20 mg group, compared with 45 days in the placebo group (the difference was not significant between omeprazole 10 and 20 mg treatment groups, each p < 0.01 compared with placebo).

Portability

There were 91 adverse events reported during the study, 33 in 19 of 61 patients receiving omeprazole 10 mg once daily; 42 in 25 of 69 patients receiving omeprazole 20 mg once daily; and 16 in 13 of 63 placebo-treated patients. The largest number of side effects were recorded from the gastrointestinal tract (13 - in the omeprazole 10 mg therapy group; 12 - 20 mg in the omeprazole 20 mg therapy group; 9 - in the placebo group). The most common symptoms observed were diarrhea and vomiting. From the cardiovascular system (10 - in the omeprazole 10 mg therapy group; 4 - in the omeprazole 20 mg therapy group; 0 - placebo), angina pectoris was most often noted. From the musculoskeletal system (2 - in the omeprazole 10 mg therapy group; 4 - in the omeprazole 20 mg therapy group; 3 - placebo) - joint pain.

Overall, the nature and frequency of adverse events were comparable between treatment groups. Regarding cardiovascular side effects, these were reported in 6 patients receiving omeprazole 10 mg (10 adverse events/one case of premature discontinuation of treatment), in 3 patients receiving omeprazole 20 mg (4 /0), and were not recorded in the placebo group. The most common (8 out of 140) reports were angina pectoris. All cases were associated with previous (before the study) cardiovascular dysfunction, for example, myocardial infarction, arterial hypertension, angina pectoris. No relationship was found between the dose of omeprazole and the incidence of adverse events from the circulatory system. No adverse events were reported in patients receiving placebo.

Discussion

The goals of long-term treatment of reflux esophagitis are:

- firstly, a steady weakening of symptoms, up to complete disappearance;

- secondly, long-term symptomatic and endoscopic remission.

For each of these targets, treatment response rates were comparable between patients receiving omeprazole 10 mg once daily and omeprazole 20 mg once daily. At the same time, omeprazole in both doses was more effective than placebo.

The use of omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg once daily achieved endoscopic remission after 1 year in 74% of patients, which is comparable to previously published data with this treatment regimen (89%1; 50%2). Despite the comparable effectiveness in preventing verified symptomatic and endoscopic relapses, according to statistical terms between the two omeprazole regimens, there was a numerical superiority when using omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg. This trend indicated a clinically significant difference between treatment regimens. Omeprazole 10 mg can be used as initial therapy. If there is no effect, you should switch to the standard (20 mg) dosage of omeprazole.

The clinical efficacy of omeprazole 10 mg in this study was greater than expected based on clinical trial results8-10. We believe that this discrepancy may be explained by the fact that many early studies involved healthy volunteers rather than patients8–9. Acid suppression achieved with omeprazole 10 mg has recently been shown to be sufficient to promote healing of duodenal ulcers in most patients10. However, in the search for predictors of the effectiveness of omeprazole 10 mg, it seems inappropriate to extrapolate data obtained in the treatment of one disease (active duodenal ulcer) to another disease (inactive reflux esophagitis).

Clinical trials focus on endpoints that are standard assessments of patients within the healthcare system. Initial assessment of relapse and decision on clinical intervention for gastroesophageal reflux disease is made routinely based on the presence/absence of disease symptoms. This practice is fully confirmed by the first three months of therapy, as proven in the present study. Endoscopy was performed after 3 months to determine whether patients continued to have inactive esophagitis. In addition, we took into account the fact that almost one third of the patients randomized to placebo (albeit in the absence of bothersome symptoms) had erosive esophagitis.

Erosive esophagitis in the absence of bothersome symptoms was detected in 13% and 10% of patients receiving omeprazole 10 mg and 20 mg, respectively. This suggests that continued absence of troublesome symptoms is a reliable indicator of sustained endoscopic healing in patients treated with omeprazole. The results support previous work demonstrating a positive association between symptomatic relief and endoscopic healing in the majority of patients treated with omeprazole11.

Hence, patients receiving omeprazole therapy are considered unlikely to require endoscopy to detect relapse, which is an important judgment given today's high demand for endoscopy and may reduce costs to the healthcare system12.

Recurrence with symptoms, even mild severity, may indicate endoscopic recurrence, and such patients require long-term treatment. Moreover, true asymptomatic relapse was rare in this study.

It can be argued that only long-term symptomatic relief is an appropriate goal, but if treatment is ineffective, there remains the suspicion of a high rate of endoscopic recurrence, which may ultimately be associated with complications including the formation of esophageal stricture or columnar metaplasia11.

Clinical studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of omeprazole not only in preventing recurrence of esophagitis, but also in preventing esophageal stricture13 and in inducing regression of columnar mucosa in Barrett's esophagus14. In this regard, long-term use of omeprazole may lead to a reduction in the incidence of complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease.

It was shown that treatment with omeprazole was associated with a decrease in the likelihood of relapse. Data on a longer survival time for patients (more than 2 times compared to placebo) receiving omeprazole therapy is a composite indicator of the therapeutic benefit of omeprazole and its good tolerability.

This study describes maintenance therapy for patients with symptoms of esophagitis. The presence of a placebo control group allows us to understand the natural history of this chronic relapsing disease. The majority of patients receiving placebo relapsed within three months of achieving remission, demonstrating the need for effective long-term treatment for reflux esophagitis . A less carefully selected population than that included in this study would contain patients with typical reflux symptoms but without esophagitis. It is not yet possible to predict which of these endoscopically “negative” patients will subsequently require treatment after achieving a satisfactory result of the initial treatment. In this study, symptomatic recurrence was intense prior to baseline esophagitis severity, while there was a positive association between the likelihood of recurrence and symptom severity immediately before treatment.

Thus, one possible conclusion may be that patients with symptoms of gastroesophageal disease, but without clear endoscopic evidence of esophagitis, are at risk of relapse. In this regard, such patients are candidates for long-term therapy.

As a conclusion, omeprazole at half the standard dose is effective in the long-term treatment of reflux esophagitis, increasing the duration of remission. Omeprazole at a dose of 10 mg per day can be used as initial or maintenance therapy.

C. Male, N. Tootsen, P. Crown, R. Nounford

Literature

- Dent J. Australian clinical trials of omeprazole in the management of refiux oesophagitis. Digestion 1990; 47 (suppl 1): 69-71.

- Lundell L., Backman L., Ekstrom P., Enander L.K., Falkmer S., Fausa O., et al. Prevention of relapse of reflux oesophagitis after endoscopic healing: the efficacy and safety of omeprazole compared with ranitidine. Scand 7 Gastroenterol 1991; 26: 248-56.

- Bate CM, Richardson PDI. Symptomatic assessment and cost effectiveness of treatments for reflux oesophagitis: comparisons of omeprazole and histamine H2-receptor antagonists. Br J Med Econ 1992; 2: 37-48.

- Isal JP, Zeitoun P., Barbier P., Cayphas JP, Carlsson R. Comparison of two dosage regimens of omeprazole—10 mg once daily and 20 mg weekends—as prophylaxis against recurrence of reflux oesophagitis. Gastroenterology 1990; 98:A63.

- Laursen IS, Bondesen S, Hansen J, Sanchez G, Sebelin E, Havelund T, et al. Omeprazole 10mg or 20 mg daily for the prevention of relapse in gastroesophageal reflux disease? A double-blind comparative study. Gastroenterology 1992; 102:A109.

- Bate CM, Booth SN, Crowe JP, Hepworth-Jones B, Taylor MD, Richardson PDI. Does 40 mg omeprazole daily offer additional benefit over 20 mg daily in patients requiring more than 4 weeks of treatment for symptomatic reflux oesophagitis? Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1993; 7:501-8.

- Bate CM, Richardson PDI. A one year model for the cost effectiveness of treating reflux oesophagitis. Br Jr Med Econ 1992; 2:5-11.

- Hemery P, GalmicheJP, Roze C, IsalJP, Bruley des Varennes S, Lavignolle A, et al. Low dose omeprazole effects on gastric acid secretion in normal man.\Gastroenterol Clin Biol 1987; 11: 148-53.

- Sharma BK, Walt RP, Pounder RE, De Fa Gomes M, Wood EC, Logan LH. Optimal dose of oral omeprazole for maximum 24 hour decrease in intragastric acidity. Gut 1984; 25: 957-64.

- Savarino V, Mela GS, Zentilin P, Cutela P, Mele MR, Vigneri S, et al. Variability in individual response to various doses of omeprazole. Dig Dis Sci 1994; 39: 161-8.

- Green J.R.B. Is there such an entity as mild oesophagitis? European J7ournal of Clinical Research 1993; 4: 29-34.

- Bate CM, Richardson PDI. Clinical and economic factors in the selection of drugs for gastroesophageal reflux disease. Pharmaco Economics 1993; 3:94-9.

- Smith PM, Kerr GD, Cockel R, Ross BA, Bate CM, Brown P, et al. A comparison of omeprazole and ranitidine in the prevention of recurrence of benign oesophageal stricture. Gastroenterology 1994; 107: 1312-8.

- Gore S, Healey CJ, Sutton R, Eyre-Brook IA, Gear MWL, Shepherd NA, et al. Regression of columnar lined (Barrett's) oesophagus with continuous omeprazole therapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1993; 7: 623-8.

Indications for use

Adults

- peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum (in the acute phase and anti-relapse treatment), incl. associated with Helicobacter pylori

(as part of complex therapy); - erosive and ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum associated with taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs);

- reflux esophagitis;

- symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease;

- dyspepsia associated with high acidity;

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Children and teenagers

Children over 2 years old weighing at least 20 kg:

- reflux esophagitis;

- symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Children over 4 years old and teenagers:

- duodenal ulcer caused by Helicobacter p y lori.

Contraindications

- sucrose/isomaltase deficiency, fructose intolerance, glucose-galactose malabsorption;

- hypersensitivity to omeprazole or other components of the drug;

- simultaneous use with nelfinavir, erlotinib and posaconazole, St. John's wort preparations;

- combined use with clarithromycin in patients with liver failure;

- children under 2 years of age;

- children over 2 years of age for indications other than the treatment of reflux esophagitis and symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease;

- children over 4 years of age for indications other than the treatment of reflux esophagitis, symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease and duodenal ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori

.

Treatment of heartburn after drinking alcohol

When dealing with heartburn, diet plays an important role. Quitting alcohol consumption is one of the mandatory items that helps reduce the risk of developing symptoms2,3. It is best to take medications to treat heartburn after alcohol has been eliminated from the body4.

Additional recommendations2,3:

- refusal of fatty, fried, spicy, sour foods;

- limiting portions;

- three meals a day, dinner 2-3 hours before bedtime;

- to give up smoking;

- wearing loose clothing;

- weight normalization;

- refusal of strong physical activity after meals;

- sleep with the head raised;

- walks in the fresh air after eating.

Bibliography:

- Instructions for use of the drug for medical use Omez® 10 mg LP 00328 dated 07/11/17 Date of access 02/01/2021.

- Lazebnik L.B., Bordin D.S., Masharova A.A. Society against heartburn // Experimental and clinical gastroenterology. – 2007. – No. 4. – P. 5-10.

- Functional gastroenterology. Directory. Gastroesophageal reflux.

- Register of Medicines of Russia RLS Patient 2003. - Moscow, Register of Medicines of Russia, 2002> Part 2. Medicine and people> Chapter 2.10. Medicines and alcohol.

Carefully

- renal and/or liver failure;

- patients with osteoporosis;

- pregnancy;

- simultaneous use with atazanavir (the dose of omeprazole should not exceed 20 mg per day), clopidogrel, itraconazole, warfarin, cilostazol, diazepam, phenytoin, saquinavir, tacrolimus, clarithromycin, voriconazole, rifampicin;

- the presence of “alarming” symptoms: significant weight loss, repeated vomiting, vomiting with blood, difficulty swallowing, change in the color of stool (tarry stools);

- deficiency of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin).

Directions for use and doses

Orally, with a small amount of water (the contents of the capsule must not be chewed).

Duodenal ulcer in the acute phase –

20 mg per day for 2-4 weeks (in resistant cases up to 40 mg per day).

Gastric ulcer in the acute phase and erosive-ulcerative esophagitis

– 20-40 mg per day for 4-8 weeks.

Erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract caused by taking NSAIDs

– 20 mg per day for 4-8 weeks.

Eradication of

Helicobacter pylori

- 20 mg 2 times a day for 7 or 14 days (depending on the treatment regimen used) in combination with antibacterial agents.

Anti-relapse treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers

– 20 mg per day.

Anti-relapse treatment of reflux esophagitis

– 20 mg per day for a long time (up to 6 months). Admission on demand (symptomatic treatment).

Symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease

- 20 mg per day for 4 weeks.

Dyspepsia associated with hyperacidity

- 20 mg per day for 4 weeks.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

– the dose is selected individually depending on the initial level of gastric secretion, usually starting from 60 mg per day. If necessary, the dose is increased to 80-120 mg per day, in which case it is divided into two doses.

Children and teenagers

Reflux esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease

For children over 2 years old and weighing more than 20 kg, the drug is prescribed at a dose of 20 mg once a day. If necessary, the dose can be increased to 40 mg once a day. The recommended duration of treatment in the case of reflux esophagitis is 4-8 weeks, in the case of symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux disease - 2-4 weeks. If symptoms do not disappear after 2-4 weeks, additional examination of the patient is recommended.

Duodenal ulcer caused by

Helicobacter pylori -

20 mg 1-2 times a day for 7-14 days (depending on the treatment regimen used) in combination with antibacterial agents.

Special patient groups

For patients with impaired renal function, no dose adjustment is required.

For elderly patients, no dose adjustment is required.

In patients with severe liver failure, the daily dose should not exceed 20 mg.

Omeprazole

Omeprazole

(lat.

omeprazole

) - antiulcer drug, proton pump inhibitor.

Omeprazole is a chemical compound

As a chemical compound, omeprazole is a derivative of benzimidazole and has the following name: (RS)-6-Methoxy-2-[[(4-methoxy-3,5-dimethyl-2-pyridinyl)methyl]sulfinyl]-1H-benzimidazole. The empirical formula is C17H19N3O3S. Characteristics of omeprazole

: white or off-white crystalline powder, highly soluble in ethanol and methanol, slightly soluble in acetone and isopropanol, very slightly soluble in water. It is a weak base, its stability depends on the acidity of the environment: it undergoes rapid degradation in an acidic environment, but is relatively stable in an alkaline environment.

Omeprazole is a medicine

Omeprazole is the international nonproprietary name (INN) of the drug.

According to the pharmacological index, it belongs to the group “Proton pump inhibitors”. According to ATC, it belongs to the group “Proton pump inhibitors” and has the code A02BC01. "Omeprazole"

, in addition, the trade name of a number of drugs.

Indications for use of omeprazole

- peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum (acute phase and anti-relapse treatment), incl. associated with Helicobacter pylori

(only as part of combination therapy!) - reflux esophagitis

- erosive and ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum associated with taking NSAIDs, stress ulcers

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome.

Method of administration of omeprazole and dose

- Orally,

before meals, with a small amount of water (the contents of the capsule must not be chewed). - Duodenal ulcer in the acute phase

- 20 mg/day for 2-4 weeks (in resistant cases - up to 40 mg/day). - Gastric ulcer in the acute phase and erosive-ulcerative esophagitis

- 20-40 mg/day for 4-8 weeks. - Erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastrointestinal tract caused by taking NSAIDs

- 20 mg/day for 4–8 weeks. - Eradication of Helicobacter pylori

- 20 mg 2 times a day for 7 or 14 days (depending on the treatment regimen used) in combination with antibacterial agents (see also Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of acid-dependent and

Helicobacter pylori-

diseases, which include and other eradication schemes). - Anti-relapse treatment of gastric and duodenal ulcers

- 10–20 mg/day. - Anti-relapse treatment of reflux esophagitis

- 20 mg/day for a long time. Available upon request. - Zollinger-Ellison syndrome

- the dose is selected individually depending on the initial level of gastric secretion, usually starting from 60 mg/day. If necessary, the dose is increased to 80–120 mg/day, in which case it is divided into 2 doses. - In patients with severe liver failure, the daily dose should not exceed 20 mg.

Omeprazole is not used to eradicate Helicobacter pylori without simultaneous use of antibiotics (that is, outside of special eradication regimens).

Publications for healthcare professionals regarding the use of omeprazole

- Maev I.V., Vyuchnova E.S., Shchekina M.I. Experience of using OMEPRAZOLE ULTOP (“KRKA”, Slovenia) in patients with duodenal ulcer. MGMSU.

- Vasiliev Yu.V. Omeprazole in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease and peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum // RMJ. – 2007. – T. 15. – No. 4.

- Gorbakov V.V., Makarov Yu.S., Golochalova T.V. Comparative characteristics of antisecretory drugs of various groups according to daily pH monitoring // Attending physician. 2001. – No. 5–6.

- Khavkin A.I., Zhikhareva N.S. Clinical experience with the use of omeprazoles from different manufacturers // Application of Consulium Medicum. Gastroenterology. 2012. No. 2. pp. 72–75.

- Bestebreurtje P., de Koning B.A.E., Roeleveld N., et al. Rectal Omeprazole in Infants With Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Randomized Pilot Trial. European Journal of Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics (2020) 45:635–643.. — Abstract in Russian

.

On the website GastroScan.ru in the “Literature” section there is a subsection “Omeprazole”, containing publications by healthcare professionals addressing the treatment of gastrointestinal diseases with omeprazole.

Contraindications to the use of omeprazole

- hypersensitivity to omeprazole

- pregnancy

- lactation

- simultaneous use with erlotinib, posaconazole *)

Restrictions on the use of omeprazole

- chronic liver diseases

- childhood (exception - Zollinger-Ellison syndrome)

- Long-term use of omeprazole or use in large doses increases the risk of hip, wrist and spine fractures (“FDA warning”).

Omeprazole therapy has no effect on driving Due to decreased secretion of hydrochloric acid, the concentration of chromogranin A (CgA) increases. Increased concentrations of CgA in blood plasma may affect the results of examinations to detect neuroendocrine tumors. To prevent this effect, it is necessary to temporarily stop taking omeprazole 5 days before the CgA concentration test *)

Use of omeprazole during pregnancy and breastfeeding

Taking omeprazole to treat GERD during the first trimester of pregnancy more than doubles the risk of having a baby with heart defects (GI & Hepatology News, August 2010).

During pregnancy, taking omeprazole is possible only for health reasons. The FDA category of risk to the fetus when treating a pregnant woman with omeprazole is “C”. Breastfeeding should be stopped during treatment with omeprazole.

At the same time, there is a position of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation: “Omeprazole is approved for use during pregnancy and during breastfeeding, in children over 2 years of age for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease, in children over 4 years of age for the treatment of duodenal ulcers caused by Helicobacter pylori

» *).

MAPS form of omeprazole

| Structure of MAPS tablets Losek MAPS (Maev I.V. et al.) |

AstraZeneca, the “successor” of Astra, which developed omeprazole, has created and patented a new dosage form of omeprazole, called its Multiple Unit Pellet System

, abbreviated MUPS or, in Russian, MAPS.

MAPS tablets contain about 1000 acid-resistant microcapsules, the tablet quickly disintegrates in the stomach into microcapsules protected from the acidic environment, then enters the small intestine, where, under the influence of alkaline pH, the microcapsules dissolve, omeprazole is released and absorbed. The MAPS form provides better delivery of omeprazole to the parietal cell, and as a result, a predictable and reproducible antisecretory effect. For erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone, MAPS tablets are as effective as omeprazole capsules. MAPS omeprazole can be dissolved in water or juice, which provides ease of use. The possibility of administering dissolved MAPS tablets through a nasogastric tube is especially relevant for seriously ill patients - the contingent of intensive care units, in whom the prevention of acute ulcers and erosions is an urgent task (Lapina T.L.).

Comparison of omeprazole with other proton pump blockers

Currently, there is no consensus among gastroenterologists regarding the comparative effectiveness of specific types of proton pump inhibitors.

Some of them argue that, despite the differences that exist between PPIs, today there is no strict evidence to judge the effectiveness of any PPI in relation to others that is noticeable for the average patient (Vasiliev Yu.V. et al.). Also, a number of gastroenterologists believe that during eradication, the type of PPI used in combination with antibiotics does not matter (Nikonov E.K., Alekseenko S.A.). Others argue that, for example, esomeprazole is fundamentally different from the other four PPIs: omeprazole, pantoprazole, lansoprazole and rabeprazole (Lapina T.L., Demyanenko D., etc.). Still others write that the antisecretory effect of Losec MAPS (omeprazole MAPS) and Pariet (rabeprazole), according to 24-hour pH measurements, is significantly superior to Nexium (esomeprazole) (Ivashkin V.T. et al.). According to Bordin D.S., the effectiveness of all PPIs for long-term treatment of GERD is similar. In the early stages of therapy, lansoprazole has some advantages in the speed of onset of effect, which potentially increases patient adherence to treatment. If it is necessary to take several drugs for the simultaneous treatment of different diseases, pantoprazole is the safest.

The differences in the antisecretory effect of lansoprazole and omeprazole are explained by the fact that the half-life of lansoprazole and omeprazole is 1.3 and 0.7 hours, respectively. The bioavailability of lansoprazole is more than 85% with the first dose and remains constant with repeated doses. When taking the first dose of omeprazole, bioavailability is only 35%, with repeated doses it increases by the third to fifth day to 60%. In addition, omeprazole is metabolized in the liver primarily by the CYP2C19 isoform of the cytochrome P450 system, and lansoprazole is additionally metabolized by the CYP3A4 isoenzyme. As a result, when taking omeprazole, a more pronounced variability of the antisecretory effect is observed depending on the heterogeneity of the CYP2C19 gene (Alekseenko S.A.).

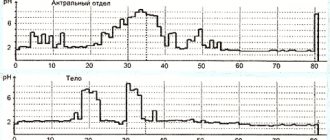

In countries - former republics of the USSR, omeprazole is widely available in generic versions. Prices for generic omeprazole are much lower than the prices for original drugs, such as Losek, Losek MAPS, Pariet or Nexium, which is of no small importance for the patient and often determines the choice of drug based on financial capabilities, especially for long-term use. Due to possible differences in the quality of drugs, an objective assessment of their clinical effectiveness is often necessary. Currently, 24-hour monitoring of intragastric pH levels is an objective and accessible method for testing antisecretory agents in clinical practice (Alekseenko S.A.).

Comparison of different omeprazole preparations

There are studies proving the advantages of some omeprazole drugs over others. For example, in a study by Khavkin A.I. and Zhikhareva N.S. it was concluded that:

- Generic omeprazole Ortanol and Omez effectively relieve the clinical symptoms of acid-related diseases in children.

- A single dose of Ortanol is more effective in comparison with Omez according to 24-hour pH measurements.

- Relief of clinical symptoms when taking the drug Ortanol occurs earlier than when taking Omez.

- Relief of symptoms on the 14th day is more complete when taking the drug Orthanol than Omeza.

- Both drugs are well tolerated.

Night Acid Breakthrough

Omeprazole, like other proton pump inhibitors, is characterized by the phenomenon of “night acid breakthrough” - a phenomenon in which, at night, regardless of the dose of the drug, there is a prolonged, more than hour, increase in acidity in the stomach (pH < 4), which sometimes makes therapy acid-related diseases are less effective.

Prof. O.A. Sablin talks about the phenomenon of “night acid breakthrough” (conference “Esophagus-2014

«)

Omeprazole resistance

The widespread use of omeprazole has determined the emergence of the term “omeprazole resistance” in modern gastroenterology, denoting the ineffectiveness of omeprazole therapy in individual patients. Resistance to omeprazole is understood as maintaining a pH in the body of the stomach below 4 for more than 12 hours with daily pH monitoring despite taking a standard dose of the drug twice. Resistance to any proton pump inhibitor is a relatively rare phenomenon and the hypothesis of its presence must be confirmed by excluding other, more common causes of ineffectiveness. The reasons for omeprazole resistance are still not fully understood. An abnormal structure of the proton pump in certain individuals is assumed, which does not allow the binding of molecules (Belmer S.V.).

Frame “Omeprazole resistance” from a video lecture for 3rd year students of the Faculty of Medicine of PSPbSMU named after. acad. I.P. Pavlova: Melnikov K.N. Drugs affecting the gastrointestinal tract

On the website in the “Video” section there is a subsection for patients “Popular Gastroenterology” and subsections “For Doctors” and “For Medical Students and Residents”, containing video recordings of reports, lectures, webinars in various areas of gastroenterology for healthcare professionals and medical students.

Interaction of omeprazole with other drugs

Omeprazole changes the bioavailability of any drug whose absorption depends on the acidity of the medium (ketoconazole, iron salts, etc.).

Slows down the elimination of drugs metabolized in the liver by microsomal oxidation (warfarin, diazepam, phenytoin, etc.). Omeprazole enhances the effect of coumarins and diphenin, but does not change the effect of NSAIDs. May increase the leukopenic and thrombocytopenic effects of drugs that inhibit hematopoiesis. The substance for intravenous infusion is compatible only with saline and dextrose solution (when using other solvents, the stability of omeprazole may decrease due to changes in the acidity of the infusion medium).

If it is necessary to take proton pump inhibitors and clopidogrel simultaneously, the American Heart Association recommends taking pantoprazole instead of omeprazole (Bordin D.S.).

When methotrexate was co-administered with proton pump inhibitors, a slight increase in plasma methotrexate concentrations was observed in some patients. When treated with high doses of methotrexate, omeprazole should be temporarily discontinued. When omeprazole is taken together with clarithromycin or erythromycin, the concentration of omeprazole in the blood plasma increases. Co-administration of omeprazole with amoxicillin or metronidazole does not affect the concentration of omeprazole in the blood plasma. There was no effect of omeprazole on antacids, theophylline, caffeine, quinidine, lidocaine, propranolol, ethanol.*)

Clarithromycin 500 mg 3 times a day in combination with omeprazole at a dose of 40 mg per day helps to increase the half-life T½ and AUC24 of omeprazole. In all patients receiving combination therapy, compared with those receiving omeprazole alone, there was an 89% increase in AUC24 and a 34% increase in T½ of omeprazole. For clarithromycin, Cmax, Cmin and AUC8 increased by 10, 27 and 15%, respectively, compared with data when clarithromycin alone was used without omeprazole. At steady state, clarithromycin concentrations in the gastric mucosa 6 hours after administration in patients receiving the combination were 25 times higher than those in patients receiving clarithromycin alone. Concentrations of clarithromycin in gastric tissue 6 hours after taking the two drugs were 2 times higher than data obtained in patients receiving clarithromycin alone.

Trade names of drugs with the active substance omeprazole

The following drugs are (were) registered in Russia: Bioprazole, Vero-Omeprazole, Gastrozol, Demeprazole, Zhelkizol, Zerotsid, Zolser, Chrismel, Lomak, Losek, Losek MAPS, Omal, Omegast, Omez, Omez Insta, Omezol, Omecaps, Omepar, Omeprazole, Omeprazole pellets, Omeprazole-AKOS, Omeprazole-Akri, Omeprazole-E.K., Omeprazole Zentiva, Omeprazole-Richter, Omeprazole Sandoz, Omeprazole-FPO, Omeprazole-Stada, Omeprazole-OBL, Omeprazole-SZ, Omeprazole-Teva, Omeprazole-Yukea, Omeprol, Omeprus, Omefez, Omizak, Omipix, Omitox, Ortanol, Otsid, Pepticum, Pleom-20, Promez, Risek, Romesek, Sopral, Ulzol, Ulkozol, Ultop, Helitsid, Helol, Cisagast.

On the pharmaceutical markets of the countries of the former republics of the USSR, a number of drugs with the active substance omeprazole are presented, which are not registered in Russia, in particular: Gasek (Mepha Lda, Switzerland), Losid (Flamingo Pharmaceutical, India), Omeprazole-Astrapharm (TOV Astrapharm, Ukraine ), Omeprazole-Darnitsa (CJSC Pharmaceutical Company Darnitsa, Ukraine), Omeprazole-KMP (JSC Kievmedpreparat, Ukraine), Omeprazole-Lugal (Lugansk Chemical Pharmaceutical Plant, Ukraine), Onex (Aarya Lifesciences Pvt. Ltd., India), Tserol (Neon Antibiotics Private Limited, India) and others.

A branded medicine with the active ingredient omeprazole on the US and Canadian markets is Prilosec (formerly called Losec). This brand is sold in Russia under the trademarks Losek Maps and Losek, in Germany, Italy and Switzerland - under the trademarks Antra and Antra MUPS.

In each of the developed countries, a large number of different drugs from different manufacturers with the active substance omeprazole are registered. For example, in Spain, omeprazole is sold (sold) under the trade names: Losec, Arapride, Audazol, Aulcer, Belmazol, Ceprandal, Dolintol, Elgam, Emeproton, Gastrimut, Miol, Norpramin, Novek, Nuclosina, Omapren, Omeprazol Abdrug, Omeprazol Accord, Omeprazol Actavis, Omeprazol Acygen, Omeprazol Almus, Omeprazol Alter, Omeprazol Apotex, Omeprazol Aristo, Omeprazol Asol, Omeprazol Aurobindo, Omeprazol Bexal, Omeprazol Biotecnet, Omeprazol Cinfa, Omeprazol Cinfamed, Omeprazol Combino Pharm, Omeprazol Combix, O meprazol Cuve, Omeprazol Cuvefarma, Omeprazol Davur , Omeprazol Desgen, Omeprazol EDG, Omeprazol Edigen, Omeprazol Esteve, Omeprazol Genericos Juventus, Omeprazol GES, Omeprazol Kern Pharma, Omeprazol Korhispana, Omeprazol Lareq, Omeprazol Liconsa, Omeprazol Mabo, Omeprazol Mede, Omeprazol Mylan, Omeprazol Normon, Omeprazol Nupral, Omeprazol Onedose , Omeprazol Ortodrol, Omeprazol Pensa, Omeprazol Pharmagenus, Omeprazol Placasod, Omeprazol Qualigen, Omeprazol Ranbaxy, Omeprazol Ratio, Omeprazol Rimazol, Omeprazol Rubio, Omeprazol Sandoz, Omeprazol Serraclinics, Omeprazol STADA, Omeprazol Sumol, Omeprazol Tar bis, Omeprazol Tecnigen, Omeprazol Teva, Omeprazol Tevagen, Omeprazol Ulcometion, Omeprazol Urlabs, Omeprazol Vir, Ompranyt, Parizac, Pepticum, Prysma, Ulceral, Ulcesep, Zimor and others.

By Order of the Government of the Russian Federation of December 30, 2009 No. 2135-r, omeprazole (capsules; lyophilisate for the preparation of a solution for intravenous administration; lyophilisate for the preparation of a solution for infusion; film-coated tablets) is included in the List of vital and essential medicines.

Instructions for medical use of omeprazole

Instructions from some manufacturers of medications containing omeprazole as the only active ingredient (pdf):

- For Russia:

- instructions for use of the drug Omez (enteric capsules, 10 mg), approved by the Ministry of Health of Russia on May 30, 2016.

- instructions for use of the drug Omeprazole-Teva (enteric capsules, 10, 20 and 40 mg), approved by the Ministry of Health of Russia on May 18, 2016.

- instructions for use of the drug Omeprazole-Ukea (lyophilisate for the preparation of solution for infusion)

- instructions for use of the drug Omeprazole-Akri, capsules containing 20 mg of omeprazole, JSC Akrikhin

- instructions for use of the drug Ultop (enteric capsules, 10 and 40 mg); changes No. 1 from 08/01/2011 to the instructions for use of the medicinal product Ultop (enteric capsules, 10 and 40 mg)

- information for healthcare professionals regarding the drug Omeprazole-Richter, capsules containing 20 mg of omeprazole, Gedeon Richter

- instructions for medical use of the drug Omeprazole, capsules containing 20 mg of omeprazole, OJSC "Kievmedpreparat"

- instructions (medical guide) for patients “Medication Guide Prilosec (omeprazole) Delayed-Release Capsules, Prilosec (omeprazole magnesium) for Delayed-Release Oral Suspensions”, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP, February 2014.

Omeprazole in the USA

Branded omeprazole in the USA is Prilosec.

In addition to it, a number of generics of omeprazole are sold in the United States. OTC (over-the-counter) in the USA Prilosec OTC and Omeprazole differ from prescription ones in the reduced amount of omeprazole in one tablet (capsule) - 20 mg. In addition, Zegerid, a drug with the active ingredient omeprazole + sodium bicarbonate, is presented on the US market. Its over-the-counter option is Zegerid OTC.

In the United States, the number of prescriptions for omeprazole is increasing annually. In 2011, omeprazole was the sixth-largest prescription drug sold in the U.S. in 2011, ahead of all digestive system drugs (although it is behind esomeprazole Nexium in terms of sales in 2011):

| Number of prescriptions for omeprazole in the United States, million per year | |||||

| 2004 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 |

| 8,6 | 27,7 | 35,8 | 45,6 | 53,5 | 59,4 |

Note.

*) Letter of the Ministry of Health of Russia dated August 15, 2014 No. 20-2/10/2-6169. On amendments to the instructions for use of medicinal products registered in the Russian Federation for medical use containing omeprazole as an active substance. Omeprazole has contraindications, side effects and application features; consultation with a specialist is necessary. Back to section

Side effect

The incidence of adverse reactions is classified according to WHO recommendations: very often >1/10, often from >1/100 to <1/10, infrequently from >1/1000 to <1/100, rarely >1/10000 to <1/1000 , very rare from < 1/10000, including isolated cases, frequency unknown - based on available data, it was not possible to determine the frequency of occurrence.

From the digestive system

:

often

– diarrhea or constipation, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, abdominal pain;

infrequently

- increased activity of liver enzymes and alkaline phosphatase (reversible);

rarely

- dry mouth, taste disturbance, stomatitis, microscopic colitis, candidiasis of the gastrointestinal tract; in patients with previous severe liver disease - hepatitis (including jaundice), impaired liver function, liver failure (in patients with previous severe liver disease).

From the nervous system

: in patients with severe concomitant somatic diseases,

headache is

common infrequently

– dizziness, vertigo, insomnia;

rarely -

agitation, drowsiness, paresthesia, depression, hallucinations;

very rarely -

aggression;

in patients with pre-existing severe liver disease,

encephalopathy is very rare

From the musculoskeletal system

:

uncommon

– fracture of the hip, wrist bones and vertebrae;

rarely

– muscle weakness, myalgia, arthralgia.

From the hematopoietic system

:

rarely

- leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, hypochromic microcytic anemia in children;

very rarely

- agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, eosinophilia.

From the skin: infrequently -

itching, skin rash, urticaria, dermatitis;

rarely

– photosensitivity;

very rarely

- exudative erythema multiforme, alopecia, Steven-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis.

Allergic reactions

: rarely - angioedema, bronchospasm, interstitial nephritis, anaphylactic reactions, anaphylactic shock, fever.

Other:

infrequently

– malaise;

rarely

- anorexia, blurred vision, peripheral edema, hyponatremia, increased sweating, gynecomastia, formation of gastric glandular cysts during long-term treatment (a consequence of inhibition of hydrochloric acid secretion, is benign, reversible); frequency unknown - hypomagnesemia.

The following are side effects, independent of the dosage regimen of omeprazole, that were noted during clinical studies, as well as during post-marketing use.

| Often (>1/100, <1/10) | Headache, abdominal pain, diarrhea, flatulence, nausea/vomiting, constipation |

| Infrequently (>1/1000, <1/100) | Dermatitis, itching, rash, urticaria, drowsiness, insomnia, dizziness, paresthesia, malaise, increased activity of liver enzymes |

| Rarely (>1/10000, <1/1000) | Hypersensitivity reactions (eg, fever, angioedema, anaphylactic reaction/anaphylactic shock), bronchospasm, hepatitis (with or without jaundice), liver failure, encephalopathy in patients with liver disease, arthralgia, myalgia, muscle weakness, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, agranulocytosis, pancytopenia, depression, hyponatremia, agitation, aggression, confusion, hallucinations, taste disturbance, blurred vision, dry mouth, stomatitis, gastrointestinal candidiasis, alopecia, photosensitivity, erythema multiforme, Stevens-Johnson syndrome, toxic epidermal necrolysis, interstitial nephritis , gynecomastia, sweating, peripheral edema, microscopic colitis. |

| Frequency unknown | Hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia due to severe hypomagnesemia, hypokalemia due to hypomagnesemia |

Cases of the formation of glandular cysts in the stomach have been reported in patients taking drugs that reduce the secretion of gastric glands for a long period of time; The cysts are benign and go away on their own with continued therapy.

Overdose

Symptoms of overdose are blurred vision, drowsiness, agitation, confusion, headache, increased sweating, dry mouth, nausea, arrhythmia.

There is no specific antidote. Treatment is symptomatic. Hemodialysis is not effective enough.

Interaction with other drugs

Long-term use of omeprazole at a dose of 20 mg 1 time per day in combination with caffeine, theophylline, piroxicam, diclofenac, naproxen, metoprolol, propranolol, ethanol, cyclosporine, lidocaine, quinidine and estradiol did not lead to changes in their plasma concentrations.

When used simultaneously with omeprazole, an increase or decrease in absorption of drugs whose bioavailability is largely determined by the acidity of gastric juice (including erlotinib, ketoconazole, itraconazole, posaconazole, iron supplements and cyanocobalamin) may be observed.

When used concomitantly with omeprazole, a significant decrease in plasma concentrations of atazanavir and nelfinavir may be observed.

When used concomitantly with omeprazole, an increase in plasma concentrations of saquinavir/ritonavir is observed by up to 70%, while the tolerability of treatment in patients with HIV infection does not deteriorate.

The bioavailability of digoxin when used simultaneously with 20 mg of omeprazole increases by 10%. Caution should be exercised when these drugs are used concomitantly in elderly patients.

When used simultaneously with omeprazole, it is possible to increase the plasma concentration and increase the half-life of warfarin (R-warfarin) or other vitamin K antagonists, cilostazol, diazepam, phenytoin, as well as other drugs metabolized in the liver via the CYP2C19 isoenzyme (a dose reduction of these drugs may be required) . Concomitant treatment with omeprazole at a daily dose of 20 mg leads to a change in coagulation time in patients taking warfarin for a long time, therefore, when using omeprazole in patients receiving warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists, it is necessary to monitor the International Normalized Ratio (INR); In some cases, it may be necessary to reduce the dose of warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist.

The use of omeprazole at a dose of 40 mg once daily resulted in an increase in the maximum plasma concentration and AUC of cilostazol by 18% and 26%, respectively; for one of the active metabolites of cilostazol, the increase was 29% and 69%, respectively.

Omeprazole, when used simultaneously, increases the plasma concentration of tacrolimus, which may require dose adjustment. During combination treatment, tacrolimus plasma concentrations and renal function (creatinine clearance) should be carefully monitored.

Inducers of the isoenzymes CYP2C19 and CYP3A4 (for example, rifampicin, preparations of St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum), when used simultaneously with omeprazole, can increase its metabolism, thereby reducing its concentration in plasma.

There was no interaction with concomitantly taken antacids. May reduce the absorption of ampicillin esters, iron salts, itraconazole and ketoconazole (omeprazole increases gastric pH). Being an inhibitor of cytochrome P450, it can increase the concentration and reduce the excretion of diazepam, indirect anticoagulants, phenytoin (drugs that are metabolized in the liver via cytochrome CYP2C19), which in some cases may require a reduction in the doses of these drugs. Strengthens the inhibitory effect on the hematopoietic system of other drugs.

When methotrexate was co-administered with proton pump inhibitors, a slight increase in the concentration of methotrexate in the blood was observed in some patients. When treated with high doses of methotrexate, omeprazole should be temporarily discontinued.

When omeprazole is taken together with clarithromycin or erythromycin, the concentration of omeprazole in the blood plasma increases.

Co-administration of omeprazole with amoxicillin or metronidazole does not affect the concentration of omeprazole in the blood plasma.

Overdose of the drug Omeprazole, symptoms and treatment

Not described. Omeprazole in a daily dose of 360 mg is well tolerated. There is no specific antidote. Omeprazole is highly bound to plasma proteins and, therefore, is poorly removed during dialysis. In case of overdose, measures are taken to remove unabsorbed omeprazole from the digestive tract, symptomatic and supportive treatment is carried out.

List of pharmacies where you can buy Omeprazole:

- Moscow

- Saint Petersburg

special instructions

Before starting therapy, it is necessary to exclude the presence of a malignant process (especially with a stomach ulcer), because Treatment, masking symptoms, can delay the correct diagnosis.

Taking it with food does not affect its effectiveness.

If you have difficulty swallowing a whole capsule, you can swallow its contents after opening or dissolving the capsule, or you can mix the contents of the capsule with a slightly acidified liquid (juice, yogurt) and use the resulting suspension for 30 minutes.

In normal dosages, the drug does not affect the speed of psychomotor reactions and concentration.

According to the study results, a pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic interaction was noted between clopidogrel (loading dose of 300 mg and maintenance dose of 75 mg/day) and omeprazole (80 mg/day orally), which leads to a decrease in exposure to the active metabolite of clopidogrel by an average of 46% and a decrease in maximum inhibition of ADP-induced platelet aggregation by an average of 16%. Therefore, the simultaneous use of omeprazole and clopidogrel should be avoided.

Due to a decrease in the secretion of hydrochloric acid, the concentration of chromogranin A (CgA) increases. Increased concentrations of CgA in blood plasma may affect the results of examinations to detect neuroendocrine tumors. To prevent this effect, it is necessary to temporarily stop taking omeprazole 5 days before the CgA concentration test.

The drug should be taken with caution if one of the following symptoms or conditions is present: the presence of “alarming” symptoms - significant weight loss, repeated vomiting, vomiting with blood, difficulty swallowing, change in the color of stool (tarry stools).

Proton pump inhibitors, especially when used in high doses and long-term use (> 1 year), may moderately increase the risk of hip, wrist, and vertebral fractures, especially in older patients or those with other risk factors.

Randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trials of omeprazole and esomeprazole, including two open-label studies with treatment durations of more than 12 years, did not confirm the association of osteoporotic fractures with the use of proton pump inhibitors.

Although a causal relationship between the use of omeprazole/esomeprazole and osteoporotic fractures has not been established, patients at risk of developing osteoporosis or osteoporotic fractures should be under appropriate clinical supervision. Severe hypomagnesemia, manifested by symptoms such as fatigue, delirium, seizures, dizziness and ventricular arrhythmia, has been reported in patients receiving omeprazole for at least three months. In most patients, hypomagnesemia was relieved after discontinuation of proton pump inhibitors and administration of magnesium supplements.

In patients who are planning long-term therapy or who are prescribed omeprazole with digoxin or other drugs that can cause hypomagnesemia (for example, diuretics), magnesium levels should be assessed before starting therapy and monitored periodically during treatment.

Omeprazole, like all drugs that reduce acidity, can lead to decreased absorption of vitamin B12 (cyanocobalamin). This must be remembered in patients with a reduced supply of vitamin B12 in the body or with risk factors for impaired absorption of vitamin B12 during long-term therapy.

Patients taking drugs that reduce the secretion of gastric glands for a long time are more likely to experience the formation of glandular cysts in the stomach, which go away on their own with continued therapy. These phenomena are caused by physiological changes resulting from inhibition of hydrochloric acid secretion.

Reduced secretion of hydrochloric acid in the stomach under the influence of proton pump inhibitors or other acid-inhibiting agents leads to an increase in the growth of normal intestinal microflora, which in turn may lead to a slight increase in the risk of developing intestinal infections caused by bacteria of the genus Salmonella

spp .

and

Campylobacter spp

., as well as possibly

Clostridium difficile

in hospitalized patients.

The mechanism of heartburn development and alcohol

The development of heartburn is based on gastroesophageal reflux - the reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. It occurs due to a single or persistent weakening of the muscular sphincter between the stomach and esophagus. The aggressive acidic environment of the stomach irritates the walls of the esophagus that are unadapted to it, which leads to a burning sensation, sometimes even chest pain3.

Risk factors for the development of heartburn are divided into several groups2,3:

- increasing acidity in the stomach;

- increasing intra-abdominal pressure;

- weakening sphincter tone;

- having a direct irritating effect on the walls of the esophagus.

Alcohol is one of the common risk factors for heartburn2. It acts in three directions at once. When consumed, alcohol has an irritating effect on the esophagus, which is aggravated if there is already inflammatory damage on its walls. Alcohol also reduces the strength of the muscle sphincter, and when it enters the stomach, it stimulates the production of hydrochloric acid2,3. Moreover, the risk of developing heartburn is not only among people who drink alcoholic beverages. Even a single dose may be enough to develop an unpleasant burning sensation behind the sternum3.