What is this

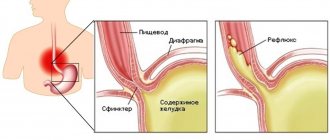

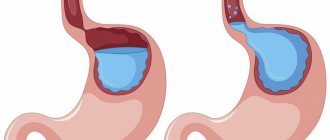

This is a form of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Hydrochloric acid, which is contained in gastric juice, has a constant aggressive effect on the mucous membrane of the esophagus. Such damage to the esophagus leads to the formation of reflux esophagitis.

Causes

Reverse reflux of the contents of the stomach and duodenum into the esophagus occurs due to a violation of the motor-evacuation function of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum. Normally, the lower esophageal sphincter prevents reflux. However, in some situations this protective mechanism does not work. There may be several reasons:

- weakening of the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter;

- deterioration in the ability of the esophagus to cleanse itself;

- increased intra-abdominal pressure;

- obesity;

- pregnancy;

- narrowing of the esophagus near the lower sphincter;

- stress;

- hiatal hernia;

- tilting the body forward (in this case, reflux will be physiological).

There are other factors that contribute to weakening the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter:

- smoking;

- alcohol;

- eating sweets and spices;

- taking medications (calcium blockers, antidepressants, antihistamines and anti-inflammatory drugs);

- weakened immune system³.

Reflux esophagitis and asthma

A study from one American clinic showed that 75% of patients with reflux esophagitis also suffer from asthma⁴. Indeed, they have common symptoms - wheezing, difficulty breathing and coughing. However, it is not asthma that provokes reflux esophagitis, but vice versa. GERD can cause asthma in people predisposed to it.

Symptoms

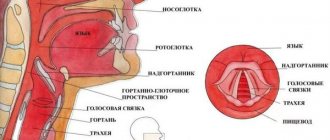

With reflux-esophagitis, parts of food and water do not move down the gastrointestinal tract, but, on the contrary, back up - into the esophagus and pharynx.

Photo: brgfx / freepik.com The most characteristic manifestations of reflux esophagitis:

- heartburn;

- nausea;

- reflux of gastric juice and food debris into the oral cavity;

- hypersalivation (excessive salivation);

- unpleasant taste in the mouth after waking up;

- difficulty and/or painful swallowing as a result of esophageal spasm;

- burning sensation in the chest area.

Important!

Often a burning sensation behind the sternum radiates to the neck and left side of the chest. Therefore, sometimes reflux esophagitis is mistaken for angina and other heart diseases.

There are also secondary symptoms of reflux esophagitis:

- hoarseness of voice;

- feeling of a lump in the throat;

- deterioration of dental condition due to damage to tooth enamel;

- inflammation of the gums;

- bad breath.

It is not at all necessary that all these clinical signs appear at the same time: even two or three symptoms from this list are quite enough to visit a gastroenterologist.

Classification by degree of damage

In modern clinical practice, several classifications based on different criteria are used. The basic classification according to the degree of damage is as follows:

1. Non-erosive reflux esophagitis. On the inner wall of the esophagus, only redness of the mucous membrane is noted.

2. Erosive reflux esophagitis. Erosive lesions are noted.

Most experts consider this classification to be too primitive, since it reflects the degree of progression of the disease only in the most general terms.

As data obtained from endoscopic studies were collected, gastroenterologists from different countries developed their own classifications with expanded morphological criteria.

Classification by A.F. Chernousova

The scientist divided esophagitis into three forms:

1. Mild esophagitis. The lower third of the esophagus is moderately hyperemic and edematous, the folds of the mucous membrane are thickened, and the esophagus itself is slightly dilated.

2. Moderate esophagitis. More severe swelling and hyperemia in the lower third of the esophagus, its lumen is expanded (but at the same time narrowed at the site of inflammation), there are erosive lesions of the mucous membrane, accompanied by bleeding.

3. Severe esophagitis. Pronounced hyperemia and swelling of the lower third of the esophagus, a significantly expanded lumen of the esophagus (at the same time there is a spasm in the affected area), the mucous membrane is ulcerated, and bleeding foci of erosion are found under fibrinous deposits.

Classification by A.F. Chernousova was adopted back in 1973 and for more than 20 years was quite popular among domestic specialists.

Hetzel-Dent classification

According to this classification, there are four degrees of the disease:

- I degree: there is hyperemia (redness) and looseness of the mucous membrane in the absence of erosive lesions.

- II degree: no more than 10% of the mucosa is involved in the erosive process.

- III degree: erosion affects no more than 50% of the mucosa.

- IV degree: erosive lesions of most of the mucosa or deep peptic ulcer in any part of the esophagus.

This classification was used until the mid-90s. Then it was replaced by the Los Angeles classification, and the Hetzel-Dent criteria began to be gradually forgotten.

Los Angeles classification

In 1996, the Congress of the World Gastroenterological Organization was held in Los Angeles. At the congress, a new classification was adopted, which has become widespread in foreign clinical practice².

| Degree | Clinical manifestations |

| A | One or more mucosal tears not exceeding 5 mm in length, none of which extends between the apices of the mucosal folds |

| B | The length of one or more mucosal tears exceeds 5 mm, and none of them extends between the upper parts of two folds of mucous membranes |

| C | Mucosal tears extend between the apices of two or more mucosal folds but occupy less than 75% of the circumference of the esophagus |

| D | Mucosal tears extend between the apices of two or more mucosal folds, occupying more than 75% of the circumference of the esophagus |

Classification according to A.N. Okorokov

In domestic clinical practice, Okorokov’s classification has taken root, which also distinguishes four degrees of severity of the disease, but with more understandable criteria:

- I degree: edematous and hyperemic mucosa, abundant mucous discharge is noted.

- II degree: in addition to edema and hyperemia, isolated erosions are observed on the mucous membrane.

- III degree: swelling, hyperemia and bleeding of the mucous membrane, multiple erosions.

- IV degree: most of the esophagus is affected by erosion, the secreted mucus acquires a viscous consistency.

Savary-Miller classification

Mention should also be made of the Savary-Miller classification, adopted in 1994 and widely used both in foreign and domestic clinical practice. At its core, it represents a slightly modified version of the Hetzel-Dent classification:

- I degree: against the background of edema and hyperemia of the mucous membrane, linear erosions are observed, which occupy no more than 10% of the circumference of the lower third of the esophagus.

- II degree: erosions merge, occupying up to 50% of the circumference of the lower third of the esophagus.

- III degree: multiple erosive lesions that occupy more than half the circumference of the lower third of the esophagus.

- IV degree: deep ulcers, strictures (narrowings) of the esophagus in the affected area, cylindrical metaplasia of the mucous membrane.

Opportunistic infections are a pressing problem of modern gastroenterology. Mycoses of the digestive organs can be caused by various microscopic fungi, but the first place in the frequency of lesions of the gastrointestinal tract, of course, is occupied by candidiasis. Diagnosis and treatment of esophageal candidiasis in some cases are associated with certain difficulties.

Yeast-like fungi of the genus Candida are single-celled microorganisms measuring 6–10 microns. These micromycetes are dimorphic: under different conditions they form blastomycetes (bud cells) and pseudomycelia (threads of elongated cells). This morphological feature has, as will be shown below, important clinical significance.

Micromycetes of the genus Candida are widespread in the environment. Viable cells of Candida spp. found in soil, drinking water, food products, on the skin and mucous membranes of humans and animals. Thus, contact of an individual’s “open systems” (skin and mucous membranes) with these micromycetes can be characterized as a completely ordinary event.

The outcome of contact with yeast-like fungi of the genus Candida is determined by the state of the individual’s antifungal resistance system. In most cases, such contact forms the so-called transient candidal carriage, when the structures and mechanisms of antifungal resistance ensure decontamination of the macroorganism. At the same time, in persons with disturbances in the antifungal resistance system, contact can form both persistent carriage and candidiasis. Thus, candidiasis of the digestive tract has typical features of an opportunistic infection.

Disease of esophageal candidiasis is mediated and determined by pathogenicity factors of Candida spp. In particular, fungal cells can attach to epithelial cells (adhesion), and then, through transformation into a filamentous form (pseudomycelium), penetrate into tissue spaces (invasion) and cause necrosis of the tissues of the macroorganism due to the secretion of aspartyl proteinases and fospholipases [1]. The listed pathogenicity factors are naturally counteracted by numerous factors of antifungal resistance. In particular, the integrity of the mucous membrane of the digestive tract and mucopolysaccharides are of great importance. A protective role is also played by the antagonism of yeast-like fungi and obligate bacteria of the digestive tract, the activity of digestive enzymes, the fungistatic effect of nonspecific humoral factors, such as lysozyme, complement, secretory IgA, transferrin, etc. However, the greatest importance in the system of antifungal resistance is the function of cells of the phagocytic series - in first of all, polymorphonuclear leukocytes, to a lesser extent - mononuclear phagocytes and natural killer cells. The specific antifungal humoral response is realized due to the synthesis by B cells of specific anti-candidal antibodies of the classes IgA, IgM, IgG and, to a certain extent, IgE. Finally, the complex cooperation of CD4 and CD8 lymphocytes and the activity of cytotoxic cells ensure an adequate specific cellular immune response.

Defects in the antifungal resistance system described above are factors contributing to the occurrence of candidiasis, or so-called risk factors. Risk groups for the development of candidiasis of the digestive tract:

- physiological immunodeficiencies (early childhood, old age, pregnancy);

- genetically determined (primary) immunodeficiencies;

- AIDS;

- oncological diseases, especially during radiation and chemotherapy;

- allergic and autoimmune diseases, especially during treatment with glucocorticosteroids;

- diseases of the endocrine system, primarily diabetes mellitus, autoimmune polyendocrine syndrome, hypothyroidism, obesity, etc.;

- dysbiosis of mucous membranes due to antibiotic therapy;

- chronic “debilitating” diseases;

- nutritional status disorders;

- transplantation of organs and tissues.

In these groups, candidiasis is detected more often than usual. Note that sometimes the cause of the violation of antifungal resistance cannot be determined.

The pathogenesis of candidiasis of the digestive tract is characterized by the sequential passage of fungi through the following stages - adhesion, invasion, candidemia and visceral lesions (Fig. 1). At the first stage, micromycetes adhere to the epithelial cells of any part of the mucous membrane. Subsequently, defects in the resistance system allow micromycetes to penetrate (invade) the mucous membrane and underlying tissues through transformation into pseudomycelium. Cytopenia is a decisive factor that allows invading fungi to reach the vascular wall, destroy it and circulate in the vascular bed. This stage is called “candidemia.” In the absence of adequate therapy, candidemia leads to the formation of foci of invasive candidiasis in visceral organs, such as the liver, lungs, central nervous system, etc.

Paradoxically, invasion of fungi of the genus Candida is more often observed in areas represented by multilayer epithelium (oral cavity, esophagus), much less often they invade single-layer epithelium (stomach, intestines).

In practice, the clinician has to deal primarily with candidiasis, the frequency of which in healthy individuals reaches 25% in the oral cavity, and 80% in the intestines. At the same time, the increase in the number of cases of candidiasis is alarming.

Examination for candidiasis of the digestive organs includes a study of the anamnesis and clinical picture, assessment of routine clinical tests, endoscopic examinations, mycological (cultural, morphological, serological) and immunological tests.

Esophageal candidiasis occurs in general patients in 1–2% of cases, in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus – in 5–10%, in patients with AIDS – in 15–30% [2]. Local risk factors may include burns, achalasia, diverticulosis, esophageal polyposis, etc. Typical complaints are dysphagia, odynophagia, and retrosternal discomfort, but a latent course of the disease is also common. Symptoms of esophageal candidiasis can interfere with the act of swallowing, which in turn leads to malnutrition and a significant decrease in quality of life.

Indications for endoscopic examination to exclude esophageal candidiasis are: risk group, clinical signs of esophagitis and verified candidiasis of other localizations (for example, oropharyngeal; candidiasis of the urogenital system; disseminated candidiasis).

Endoscopic signs of esophageal candidiasis are hyperemia and contact vulnerability of the mucous membrane, as well as fibrinous deposits of various locations, configurations and sizes. Among the variety of visual signs of esophageal candidiasis, three groups of typical changes can be distinguished:

- Catarrhal esophagitis. Diffuse hyperemia of varying degrees (from mild to pronounced) and moderate swelling of the mucous membrane are observed. A characteristic endoscopic sign is contact bleeding of the mucous membrane, sometimes with the formation of a delicate, whitish (“web-like”) coating on the mucous membrane. No erosive changes are noted.

- Fibrinous (pseudomembranous) esophagitis. White-gray or white-yellow loose plaques are observed in the form of rounded plaques with a diameter of 1–5 mm, protruding above the brightly hyperemic and edematous mucous membrane. Contact vulnerability and hyperemia of the mucous membrane are noticeably expressed (Fig. 2).

- Fibrinous-erosive esophagitis. Characteristic is the presence of dirty gray “fringed” plaques in the form of “ribbons” located on the crest of the longitudinal folds of the esophagus.

With instrumental separation of such plaques, the eroded mucous membrane is exposed. Erosion can be round or linear, usually from 0.1 to 0.4 cm in diameter. The mucous membrane of the esophagus is extremely vulnerable, swollen and hyperemic. Severe changes in the mucous membrane sometimes prevent a full endoscopic examination of the esophagus (bleeding, pain and anxiety of the patient, stenosis of the esophagus caused by edema) [3].

Let us recall that similar endoscopic changes can be observed with reflux esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, herpes esophagitis, flat leukoplakia, lichen planus, burn or tumor of the esophagus. Therefore, diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis is based on endoscopic examination and laboratory examination of biopsy materials from the affected areas. It must be taken into account that with a single biopsy, the sensitivity of laboratory methods is insufficient.

The “gold standard” for diagnosing candidiasis of the mucous membranes is the detection of pseudomycelium of Candida spp. during morphological examination (Fig. 3).

In order to detect pseudomycelium, morphological mycological methods are used: cytological - with staining of smears according to Romanovsky-Giemsa and histological - with staining of biopsy specimens with the PAS reaction. Thus, taking into account the dimorphism of micromycetes Candida spp. is the key to the differential diagnosis between candidiasis and candidiasis. In modern conditions, the clinician must demand from the morphologist an accurate description of the morphological structures of the fungus - after all, the detection of blastomycetes, as a rule, indicates candidiasis, and the detection of pseudomycelium allows us to confirm the diagnosis of candidiasis.

The disadvantages of morphological methods include their limited sensitivity for endoscopic biopsy. It is well known that biopsy forceps allow one to obtain a miniature fragment of tissue for study and the likelihood of detecting an informative sign with a single biopsy is insufficient.

The cultural mycological method is based on sowing biomaterials of mucous membranes on Sabouraud's medium. The advantage of this method is the possibility of species identification of fungi of the genus Candida and testing the culture for sensitivity to antimycotics. The relevance of such studies is due to the fact that different species of Candida, in particular C. albicans, C. tropicalis, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei, C. glabrata, have different sensitivities to modern antifungal drugs. The disadvantage of the cultural method is the inability to differentiate candidiasis and candidiasis when studying materials from “open systems”, since mucous membranes can normally be contaminated with colony-forming units of Candida spp.

A cultural study of biomaterials of the mucous membranes with determination of the type of pathogen becomes absolutely necessary in case of recurrent candidiasis or resistance to standard antimycotic therapy [4, 5].

The sensitivity and specificity of serological tests for diagnosing esophageal candidiasis (enzyme immunoassay with Candida antigen, level of specific IgE, Platelia latex agglutination test) have not yet reached the required accuracy and are rarely used in practice.

Candidiasis of the esophagus, even if it occurs subclinically, is dangerous due to its complications - stricture, bleeding, perforation and dissemination of mycotic lesions.

The radiographic method for candidiasis of the digestive organs is of little information, since it does not specify the etiology of the process, but with the development of complications (for example, with stricture, ulcer, perforation) it becomes crucial.

The development of esophageal strictures is noted in 8–9% of patients with candidal esophagitis. More often they are localized in the upper or middle third of the thoracic esophagus and cause permanent dysphagia [6]. Another common complication of candidiasis in the upper digestive tract is bleeding caused by contact vulnerability of the mucous membrane. Chronic low-intensity bleeding leads to anemia, and in patients with cytopenia, bleeding can develop rapidly (vomiting of scarlet blood and pseudomembranous masses is often observed) and, due to blood loss, lead to shock. The clinical picture of esophageal perforation, in addition to intense pain, is characterized by the development of pneumomediastinum and subcutaneous emphysema in the neck.

The management plan for patients with esophageal candidiasis must include diagnosis and correction of underlying diseases, sanitation of other foci of candidal infection, rational antifungal therapy and immunocorrection. At the clinic of the Research Institute of Medical Mycology of St. Petersburg MAPO, a patient with esophageal candidiasis has his blood tested for antibodies to HIV, tests are performed to exclude glucose tolerance, as well as tests to determine the number and function of circulating immunocompetent cells. Since esophageal candidiasis can be a marker of cancer, the examination plan includes an X-ray examination of the chest organs and fibrosigmoscopy, as well as additionally, for men, ultrasound of the prostate gland, for women, ultrasound of the mammary glands and pelvic organs with consultation with a gynecologist.

Treatment of esophageal candidiasis is based on the use of antifungal drugs. The general principle of action of all antifungal agents is inhibition of the biosynthesis of ergosterol in the cell wall of micromycetes. Antifungals used to treat esophageal candidiasis can be divided into three groups. The first group is polyene antimycotics, which are practically non-resorbable when taken orally. Among them, amphotericin B is used. Other polyene drugs, such as nystatin and natamycin, are ineffective in the treatment of esophageal candidiasis. The second group is azole antimycotics, which are relatively well absorbed when taken orally. These include: ketoconazole, fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, albaconazole, posaconazole. The third group is the most modern echinocandin antimycotics: caspofungin, anidulafungin, micafungin.

The goal of treatment of candidiasis of the mucous membranes of the upper digestive tract is to eliminate symptoms and clinical and laboratory signs of the disease, as well as to prevent relapses.

For esophageal candidiasis, local therapy is ineffective. In patients with severe odydysphagia who are unable to swallow, parenteral therapy should be used.

The drug of choice for the treatment of candidiasis of the mucous membranes of the upper digestive tract is fluconazole at a dose of 2.5–3 mg/kg/day (100–200 mg/day), prescribed for 14–21 days [7–9]. It should be noted that, as a treatment for esophageal candidiasis, fluconazole is superior in effectiveness to both ketoconazole and itraconazole capsules due to the variable absorption of the latter.

It is known that both in HIV infection and in HIV-uninfected patients, the most common causative agent of esophageal candidiasis is C. albicans. However, infections caused by C. Glabrata, C. krusei and other Candida species, sometimes resistant to fluconazole treatment, have also been described.

In cases of ineffectiveness of standard fluconazole therapy, one of the alternative treatment methods can be used: itraconazole oral solution 200 mg/day, amphotericin B 0.3–0.7 mg/kg/day intravenously, voriconazole 4 mg/kg 2 times a day intravenously, Micafungin or caspofungin 50 mg/day intravenously. The duration of therapy is usually 2–3 weeks.

Despite the high effectiveness of fluconazole, in patients with a persistent immunodeficiency state there is a high probability of relapse of esophageal candidiasis. It must be remembered that a relapse-free course of candidiasis can only be achieved in patients with complete correction of the background condition. Thus, in AIDS, relapses of candidiasis stop only with successful highly active antiretroviral therapy, which ensures a decrease in the viral load and an increase in the number of CD4 lymphocytes.

At the clinic of the Research Institute of Medical Mycology of St. Petersburg Medical Academy of Postgraduate Education, 128 patients with esophageal candidiasis aged 16 to 72 years were examined, including 41 (32%) men and 87 (68%) women. The absence of HIV infection in patients was proven by at least two serum tests. The diagnosis of esophageal candidiasis was confirmed by the detection of esophagitis during endoscopic examination, as well as the identification of pseudomycelium of Candida spp. by microscopy of smears and growth when inoculating biopsy samples of the esophageal mucosa.

When examining patients, the following background diseases were identified: rheumatological diseases, mainly rheumatoid arthritis - 19 (14.8%) cases, hormone-dependent bronchial asthma - 14 (10.9%), type 1 diabetes mellitus - 12 (9.4%), malignant tumors, mainly of the stomach – 10 (7.8%). In 73 (57%) patients, typical risk factors for the development of mucosal candidiasis could not be identified. All patients received a course of antifungal therapy with fluconazole (100–200 mg/day for 14 days) or ketoconazole (200 mg/day for 20 days). Control endoscopic and laboratory mycological tests confirmed complete cure of the primary episode of esophageal candidiasis.

However, control endoscopic and laboratory studies performed during the first 6 months after treatment of the primary episode revealed recurrence of esophageal candidiasis in 49 (38.3%) patients. Of these, 10 (20.4%) people with recurrent esophageal candidiasis suffered from type 1 diabetes mellitus, 16 (32.7%) from rheumatological diseases, 7 (14.3%) from malignant tumors, and 9 (18%) from hormone-dependent bronchial asthma. ,4 %). In 7 (14.3%) patients, factors predisposing to recurrence of esophageal candidiasis could not be identified [10].

To prevent relapses, long-term maintenance therapy with fluconazole (100 mg/day) or the administration of fluconazole 200 mg weekly may be effective [11, 12]. It should, however, be noted that repeated courses of treatment or the use of long-term therapy for the management of patients with recurrent candidiasis are the main risk factors for the development of azole-refractory strains of fungi.

Diagnostics

If you have symptoms of reflux-esophagitis, you should contact a gastroenterologist.

Photo: Shidlovski / Depositphotos First of all, the doctor collects an anamnesis (medical history): it is necessary to collect complaints, obtain information about concomitant and previous diseases, and also get an idea of the patient’s diet.

General blood analysis

An increased level of leukocytes indicates inflammatory processes. With erosion and ulcers of the esophagus, bleeding occurs, which in a general blood test is manifested as iron deficiency anemia.

Important!

The disadvantage of a general blood test is that it gives only a general idea of the processes occurring in the body, without giving a clear idea of their localization.

Fibroesophagogastroduodenoscopy (FEGDS)

The examination is carried out using an endoscope - a thin flexible tube with a miniature lens at the end. In addition to the esophagus, the doctor can examine the stomach and duodenum to fully clarify the clinical picture. Sometimes the study is limited only to examination of the esophagus (esophagoscopy).

It is with FEGDS that one can visually determine the very changes that are considered as the main criteria when classifying the severity of reflux esophagitis.

How to prepare for FEGDS?

The procedure is unpleasant, but generally painless. Usually the entire study takes no more than 10 minutes. You need to follow simple rules:

- Do not eat or drink (at least 8 hours must pass after your last meal).

- Do not smoke (3-4 hours before the test).

- Do not take medications (except for those that cannot be skipped - this point should be discussed with your doctor. As a rule, it is allowed to give medicinal injections and take lozenges).

- One day before, you need to give up fatty foods (cheeses, sausages, fatty meats and fish, fried foods, etc.).

- In 2–4 hours, you can drink a couple of sips of regular water without carbon.

- Immediately before the procedure, remove glasses and dentures.

Biopsy

This test is performed simultaneously with endoscopy. A small section of esophageal tissue is taken for histological examination. A biopsy is not prescribed for all patients: it is necessary if malignancy is suspected.

Radiography

This test helps identify ulcers, swelling, and mucus accumulations. To improve visualization, the patient is offered to drink a contrast agent - barium. This substance tastes like liquefied chalk. This liquid is non-toxic and is freely absorbed in the intestines.

Daily pH-metry

This test is prescribed to determine the level of acidity in the esophagus. In a healthy person, the pH level is always above 4.0 (in other words, an alkaline environment predominates). With frequent reflux of gastric juice into the esophagus, a shift occurs towards increased acidity.

A thin probe is inserted into the patient's esophagus through the nostril. The outer end of the probe is connected to a sensor that reads information about changes in the pH environment. A few days before the test, the doctor gives the patient a list of medications (antacids, nitrates, calcium channel blockers), which should be avoided for 2-3 days before the test to obtain an objective result. Approximately 5 hours before the start of the study you should refrain from eating.

Additional Research

Sometimes differential diagnosis is carried out, which allows us to exclude another disease with similar symptoms. For example, if bronchitis is suspected, a chest x-ray is prescribed, and an ECG is performed to exclude angina from the list of possible diseases.

Inflammatory diseases of the esophagus

Inflammatory diseases of the esophagus include:

- Acute esophagitis.

- Chronic esophagitis.

- Refluxesophagitis.

- Peptic ulcer of the esophagus.

The last two diseases are the result of systematic irritation of the esophageal mucosa by the acidic contents of the stomach, causing inflammation and tissue degeneration.

Acute esophagitis.

Acute esophagitis occurs as a result of acute bacterial or viral infection. They have no practical significance during the course of the disease and disappear along with other signs of the disease if they do not acquire an independent chronic course.

Acute esophagitis can be:

- Catarrhal esophagitis.

- Hemorrhagic esophagitis.

- Purulent esophagitis (abscess and phlegmon of the esophagus).

The causes of acute esophagitis are a chemical burn (exfoliative esophagitis) or trauma (bone splinter, injury from swallowing sharp objects, bones).

Clinical picture of acute esophagitis . Patients with acute esophagitis complain of pain behind the sternum, aggravated by swallowing, and dysphagia is sometimes noted. The disease occurs acutely. It is also accompanied by other signs characteristic of the main process. With the flu, this is a fever, headache, pain in the throat, etc. With a chemical burn, there are indications for ingesting alkali or acid; traces of a chemical burn are found on the oral mucosa, in the pharynx. Abscess or phlegmon of the esophagus is characterized by severe pain behind the sternum when swallowing, difficulty swallowing solid food, while warm and liquid food does not linger in it. Signs of infection and intoxication appear - increased body temperature, leukocytosis in the blood, ESR is increased, and proteinuria occurs.

X-ray examination makes it possible to detect an infiltrate that causes some retention of the food bolus, to establish its location and the degree of damage to the wall of the esophagus.

Esophagoscopy : the mucous membrane in the area of infiltration is hyperemic and edematous. Upon careful examination, you can find a splinter - a fish bone or a sharp bone stuck in the tissue of the esophagus. Using forceps, the foreign body is removed. With the edge of the device it is possible to feel the density of the infiltrate. If the abscess is mature, soft tissue is detected in the center.

Diffuse esophagitis is accompanied by hyperemia and swelling of the mucous membrane. It is covered with a white-gray coating and bleeds easily. Erosion has an irregular shape, often longitudinal, and is covered with a gray coating. Peristalsis is preserved.

Acute esophagitis can occur without consequences. After a chemical burn, powerful scars develop, causing a narrowing of the esophagus.

Chronic esophagitis.

Chronic esophagitis is caused by tuberculosis bacteria, syphilis pathogens, and fungi (candidiasis, blastomycosis). A special form is peptic esophagitis, which develops as a result of reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Chronic lesions of the esophagus are formed against the background of collagenosis (scleroderma), vitamin deficiencies, iron deficiency anemia (Plummer-Vinson syndrome), severe heart failure, and portal hypertension. Sometimes chronic idiopathic ulcerative esophagitis is found.

Clinical picture of chronic esophagitis. In all cases, chronic esophagitis causes burning, pain behind the sternum, at the xiphoid process, which intensifies when swallowing. Dysphagia is rare. At the same time, patients exhibit signs of the underlying disease: prolonged fever, intoxication, leukocytosis, increased ESR, erythrocytosis, anemia and a number of other signs. These circumstances force the doctor to conduct a more thorough examination of the patient.

X-ray and esophagoscopic examination are of great help in diagnosing chronic esophagitis.

Peptic esophagitis (reflux esophagitis).

Peptic esophagitis (reflux esophagitis) - this disease is the result of systematic reflux of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus. The causes of peptic esophagitis are not well understood. In some cases, a diaphragmatic hernia is found, the stomach protrudes into the chest, and the suction effect of the chest during respiratory movements. The main mechanism of the disease is dysfunction of the cardiac sphincter.

Clinical picture of reflux esophagitis. The most common complaint with reflux esophagitis is an indication of heartburn, a burning sensation in the epigastric region, behind the sternum or throughout the abdomen. Heartburn is often followed by pain of a paroxysmal nature, which is associated with spastic contraction of the esophagus. Pain may occur when swallowing under the influence of irritating food. Regurgitation is the second most common sign. It can be observed day and night, during sleep. Regurgitation is provoked by coughing, overeating, and bending over. Heartburn, regurgitation, chest pain depress the patient’s psyche. Signs of depression begin.

X-ray examination: a spasm of the esophagus or a reflex spasm in the cardiac part is detected. Peristalsis is not impaired. The progress of barium suspension is slowed down. The mucous membrane of the esophagus in certain areas is diffusely thickened, its elasticity is reduced. Regurgitation of stomach contents into the esophagus is observed. The contour of the esophagus may be uneven, the folds are smoothed, deformed.

Esophagoscopy : a picture of focal or diffuse inflammation is detected. Usually the mucous membrane of the cardiac part of the esophagus is affected. The changes are mainly catarrhal in nature. Erosion is less common.

Peptic ulcer of the esophagus.

Ulcers and erosions of the esophagus occur quite often and in many diseases - benign and malignant tumors, chronic inflammatory processes, etc. However, a peptic ulcer of the esophagus is understood as a completely unique disease, which in some ways resembles peptic ulcers of the stomach and duodenum. Ulcers of the esophagus and stomach or duodenum are often combined. A certain importance in the occurrence of peptic ulcers is attached to the nervous mechanism associated with injuries and diseases of the brain (meningitis, meningoencephalitis, damage to the hypothalamic region). However, local mechanisms of ulcer formation (impaired blood circulation in tissues, dystrophy, decreased function of protective factors, dysfunction of the obturator mechanism of the cardia and inconsistency in its work with gastric motility) also have great pathogenetic significance.

Clinical picture. The most important signs of a peptic ulcer of the esophagus are pain that occurs and intensifies while eating, dysphagia, heartburn, and there may be vomiting. The pain is localized in the area of the xiphoid process, less often higher, behind the sternum. Sometimes they appear 10-30 minutes after eating at the height of digestion. Dysphagia is associated with spasm of the esophagus, but can be caused by cicatricial narrowing of the cardia.

X-ray examination reveals a contrast agent depot - a “niche” with an inflammatory shaft around it. Its shape and size are different - from 0.2 mm to 20-30 mm. Peristalsis of the esophagus is increased. Above the ulcer, the esophagus is widened, the folds of the mucous membrane are rough, oriented towards the base of the “niche”. A spasm may be detected in the ulcer area. Ulcers of the esophagus can be either single or multiple.

Esophagoscopy: peptic ulcers are located in the distal parts, have a round or elongated irregular shape, often superficial. The bottom is covered with a yellow-gray coating, after removing which the bleeding surface is exposed. The edges are infiltrated and slightly rise above the surface. The mucous membrane around the ulcer is hyperemic. After the ulcer heals, a whitish scar remains. Less commonly, scars cause a narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus.

According to the clinical course, ulcers of the esophagus are distinguished:

- Neurotrophic ulcers of the esophagus. They occur in people with brain diseases (tumors, inflammation).

- Decubital ulcers of the esophagus, developing in old people with reduced body resistance to infection and with spondyloarthrosis.

- Peptic ulcer of the esophagus proceeds sluggishly and recurs. Its course is determined by the course of the stomach disease - peptic ulcer, hypersecretion and the course of disorders of the function of the nerve centers that regulate the functioning of the cardia.

Serious complications are observed: cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus, perforation of an ulcer into the abdominal or chest cavity with the formation of purulent peritonitis or pleurisy, pericarditis.

The diagnosis of peptic ulcer of the esophagus is based on characteristic clinical signs, the presence of a “niche” on the radiograph and esophagoscopy data. The disease in question can be differentiated from a cancerous tumor by microscopic examination of scrapings from the “niche” (with cancer, atypical cells are found). The post-ulcer scar has a characteristic star-shaped shape. The post-ulcer scar can be distinguished from the syphilitic scar by the indicators of the Wasserman, Kahn, and cytocholic tests. With a hernia of the diaphragm, esophagitis and peptic ulcer of the esophagus are detected. The hernia is detected by X-ray examination. Esophageal stenosis in most cases is a consequence of achalasia, chemical burns, inflammatory diseases of the esophagus (tuberculosis, injury, phlegmon, mediastinitis, syphilis). They can occur in diseases of other organs - tumors of the lungs and mediastinum, aortic aneurysm, etc., which is associated with compression of the organ from the outside. Occasionally, developmental anomalies of the esophagus occur, which lead to a narrowing of its lumen. Cicatricial changes in the esophagus are accompanied by thick deposits of connective tissue in the wall; this circumstance limits its extensibility during swallowing. Retention of food above the narrowing leads to stretching of the esophageal wall, inflammation and ulceration of the mucous membrane. Post-burn stenoses usually have a significant extent and are most often located in places of physiological narrowing: aortic, pharyngoesophageal or diaphragmatic.

The main clinical symptoms of esophageal stenosis are dysphagia, esophageal vomiting, and weight loss. Dysphagia can be expressed in different ways - from discomfort when swallowing food to the complete inability to eat. Earlier, difficulties arise with swallowing dry food; later, difficulties arise with swallowing liquid food. Regurgitation appears, then esophageal vomiting. Aspiration of esophageal contents is possible.

The diagnosis is confirmed by the results of X-ray or esophagoscopic examination.

Treatment of inflammatory diseases of the esophagus.

In the treatment of esophagitis, a gentle diet is used. For chemical burns of the esophagus, after gastric lavage, only warm (36°C) liquid food is given. In case of severe burns, parenteral nutrition (hydrolysates, glucose solutions, polyglucin) is used for several days. The patient is injected intravenously with up to 2 liters of fluid and blood substitutes. In the future, if the condition allows, the dietary regimen is expanded gradually. The fight against infection is carried out only if it is the cause of esophagitis. In case of abscess and phlegmon of the esophagus, they try to remove the splinter that caused the inflammation. Broad-spectrum antibiotics (oxacillin, ampicillin, chloramphenicol, olemorphocycline, kanamycin, gentamicin, etc.) are used in a sufficient daily dose. Antibiotic treatment begins early. Thus, ampicillin is prescribed intramuscularly at 0.5 g 4 times a day, kanamycin - 0.5 g 6 times a day. The duration of treatment is at least 7-10 days, provided that on the second to third day from the start of treatment, body temperature has normalized and signs of intoxication have decreased. In case of a chemical burn of the esophagus, antibiotics are indicated for prophylactic purposes, since chemical ulcers begin to fester very quickly. In cases where patients have increased gastric secretion and high acidity of gastric juice, alkalizing therapy is necessary. Almagel A is used one teaspoon 3-4 times a day. Aluminum hydroxide, white clay or magnesium trisilicate with the addition of sodium bicarbonate are also prescribed. Spasm of the esophagus is eliminated with the help of drugs atropine, papaverine, and no-shpa. Spasmolitin, arpenal, and metacin are also used. A number of patients use those treatment methods that are indicated for gastric or duodenal ulcers, including ganglion blockers (benzohexonium).

Physiotherapy for diseases of the esophagus is carried out using galvanic procedures, inductotherapy, microwave therapy, as well as mud therapy and paraffin therapy. The choice of method and method of application of the procedures are determined by the nature and stage of the disease of the esophagus and stomach. Thermal procedures should be avoided if a deep ulcer of the esophagus is suspected, which may cause bleeding.

Patients with chronic esophagitis and peptic ulcer of the esophagus should be monitored by a local doctor. Patients are examined by clinical, radiological and esophagoscopic methods 1-2 times a year. In the presence of an active ulcerative process, treatment is carried out in a hospital. Periodically, in order to prevent exacerbation of the disease, courses of preventive treatment and physiotherapy are carried out. Treatment in sanatoriums at resorts with drinking mineral waters has the same preventive value. Cicatricial narrowing of the esophagus is treated by dilatation, bougienage, and more often with flexible plastic bougie. Surgical treatment is used in cases of stenosis of the esophagus, as well as perforation or cancerous degeneration of the organ.

If you have any questions. Then you can get advice from leading multidisciplinary medical specialists

Treatment of reflux esophagitis

The disease is characterized by a chronic course.

Therefore, you will need not only to take a course of pills, but also to include competent and healthy nutrition in your life. Photo: katemangostar / freepik.com Treatment of the disease requires an integrated approach, and reflux esophagitis is no exception in this sense. It is necessary to choose the right medications, normalize your lifestyle and adjust your diet. Each of these elements of complex therapy is important in its own way, but individually it is not effective enough.

Important!

Treatment of reflux involves a comprehensive approach: medications, diet and a healthy lifestyle. Therefore, people who rely solely on pills will be disappointed: they will have to give up some bad habits and favorite foods.

Lifestyle correction

First of all, it is necessary to normalize intra-abdominal pressure. To do this, you will have to limit physical activity and give up tight clothing (especially belts).

It is important to understand that with persistently elevated intra-abdominal pressure, medications and diet will not give the expected result. You still need to adjust your lifestyle.

Lifestyle with reflux

- Avoid stress and nervous overload.

- Sleep at least 8 hours a day - this is exactly how much is needed for proper rest and restoration of nervous system resources.

- To reduce the likelihood of nighttime reflux, choose a small pillow that provides a head angle of about 30 degrees.

- Give up the habit of lying down after eating. This is, of course, convenient, but harmful to digestion. In a lying position, the likelihood of reflux increases many times.

Diet

Almost any diet involves removing the most delicious foods from the diet. All that remains is to come to terms with this and call on willpower to help. Otherwise, the treatment will not give the desired effect. The following should be excluded from the menu:

- alcohol: alcoholic drinks not only relax the lower esophageal sphincter, but also increase the secretion of gastric juice. As a result, its quantity increases, which, combined with sphincter relaxation, leads to reflux;

- carbonated drinks: they also increase the secretion of hydrochloric acid, which forms the basis of gastric juice, and irritate the gastric mucosa;

- chocolate: relaxes the lower esophageal sphincter;

- acid-forming products: ketchup, mayonnaise, mustard, tomato sauces.

- legumes and cabbage: increase gas formation and increase intra-abdominal pressure;

- fatty (sausages, cheeses, fatty meats and fish), spicy foods (spices) and fried foods (especially with a lot of oil: French fries, onion rings, etc.);

- muffins, cakes, pastries;

- canned food;

- fast food.

Important!

Doctors have not yet come to a conclusion about whether a gluten-free diet is beneficial for reflux esophagitis. The best thing to do is to abstain from foods containing gluten and see the results. Perhaps this is the right decision for your body.

Features of the diet

Preference should be given to:

- boiled dishes;

- baked;

- stewed;

- steamed.

The main thing is not to overfill your stomach: this will help reduce the amount of gastric juice produced.

How to eat properly with reflux esophagitis

- Small meals (4–5 times a day).

- Chewing food thoroughly.

- Liquid: no more than 1.5 liters per day.

- Salt: maximum 10 g per day.

- Exclude: alcohol, soda, chocolate, legumes, cabbage.

- Replace fatty fried foods with boiled, stewed, baked ones.

- Don't lie down after eating!

- Don't eat before bed!

Energy value of the diet

The upper recommended limit for the consumption of proteins, fats and carbohydrates is as follows:

- proteins - 90 g (about half of which are of animal origin);

- fats - 80 g;

- carbohydrates - 300 g.

Daily diet and calories

The energy value of the daily diet should not exceed 2,500 kilocalories per day.

This is a fairly comfortable norm for a person who is not prone to overeating. For example:

- a bowl of chicken soup contains approximately 360 kcal, 15 g of protein, 30 g of fat and 20 g of carbohydrates;

- a plate of boiled potatoes with one large cutlet - about 20 g of protein, 10 g of fat, 35 g of carbohydrates and 280 kcal.

But the calorie content of one small custard cake is approximately 400 kcal. Thus, if you do not abuse sweets, the recommended daily calorie intake does not impose significant restrictions on the patient.

Food must be chewed thoroughly. This not only promotes better digestion, but when a person eats in a hurry, this inevitably leads to air entering the stomach and causing reflux.

Drug treatment

In the treatment of reflux esophagitis, several groups of drugs are used:

1. Prokinetics. Drugs in this group improve the motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract and increase the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (domperidone, genaton).

2. Antacids. Preparations based on algeldrate and magnesium hydroxide neutralize the increased acidity of gastric juice.

3. Antisecretory drugs. Reduce the formation of gastric juice (omeprozole, famotidine).

Surgery

If complex conservative treatment does not give the desired result within six months, the patient is recommended for surgical treatment. Its essence lies in stitching the sphincters of the esophagus to normalize their barrier function. These operations can be performed using both the abdominal (classical) and endoscopic methods. The advantage of the second option is that the patient does not have scars on the abdomen and chest.

An additional indication is the development of complications, which include:

- pneumonia (develops as a result of regular reflux of gastric juice into the respiratory tract);

- bleeding;

- Barrett's esophagus (a precancerous condition in which pathological changes occur in the epithelial tissues of the esophagus);

- persistent stricture (narrowing) of the esophagus³.

Disease prevention

Patients often themselves notice which foods or habits lead to a worsening of the situation.

It is important to listen to your body. Photo: ponomarencko / freepik.com Prevention of esophagitis caused by regular refluxes is aimed at preventing them and is closely related to lifestyle correction, which we have already discussed above.

7 rules for preventing reflux esophagitis

- Follow a diet.

- If possible, avoid taking drugs that reduce the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (antidepressants, tranquilizers, sedatives and anticholinergics).

- Immediately after eating, do not lie down - it is better to stand for a while, walk or wash the dishes.

- After eating, doctors also do not recommend playing sports or other physical activities, so as not to increase intra-abdominal pressure.

- Keep the amount of alcohol consumed to a minimum.

- Quit smoking.

- Don't overeat.