Perforated ulcers are a worldwide problem and an emergency with mortality rates of up to 30%. The paucity of high-quality research on this condition limits the evidence base for clinical decision-making, but several published randomized trials are available. Although Helicobacter pylori and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use are common causes, demographic differences in age, sex, location of perforation, and existing underlying causes and mortality vary among countries. Clinical prediction rules are used, but the accuracy of the prediction varies with the population being studied. Early surgical intervention, such as laparoscopic or open removal of the ulcer, as well as proper management of patients in the event of sepsis are essential to obtain a good result. Some patients can be treated conservatively or with new endoscopic techniques, but such techniques need to be tested in clinical trials. Quality of care, stratification of sepsis care, and postoperative monitoring require further evaluation. Adequate studies with low risk of bias are urgently needed to provide more accurate data. We summarize the evidence for management approaches for patients with perforated ulcers and identify directions for future clinical research.

1.General information

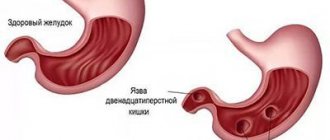

An ulcer is a long-term non-healing inflamed wound surface on the epidermal (external, skin) or mucous membrane. It should be immediately clarified that the concepts “ulcer” and “erosion”, often confused and even used as synonyms, are not the same thing. Unlike erosion or a superficial scratch, an ulcer penetrates into the deep, base layers of the corroded surface, which leads to the irreversible loss of one or another volume of tissue, and consequently to losses in its functionality. Healing of ulcers occurs by partial or complete replacement of the defect with connective tissue (“healed ulcer”).

The old Russian verb “pierce” means to make a hole, break through, pierce, pierce; The Latin word “perforate” has the same meaning, which has many derivatives both in the world of technology and in medicine.

Thus, a perforated (perforated) ulcer is an ulcer through and through, an ulcer with a violation of the tightness and the formation of a “hole”. The term “perforated ulcer” is used only in gastroenterology and implies an aggressive ulcer of the stomach or duodenum - as their walls become thinner, they can eventually break through; in every tenth case, the effusion of contents into the abdominal cavity is also accompanied by massive bleeding. In general, perforation of a gastroduodenal ulcer is one of the most dangerous and severe outcomes of peptic ulcer disease, creating an immediate threat to the patient’s life.

Considering the prevalence of ulcerative-inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (several million people suffer from them in Russia alone), there is no need to talk for long about the severity and relevance of the problem of perforated ulcers. Today, one of the main tasks of gastroenterology remains the development not so much of diagnostic and emergency surgical protocols (see below), but of methods for accurately assessing the type of course and dynamics of peptic ulcer disease, as well as reliable prediction and reliable prevention of its perforated variants.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

Authorized Products

The diet after gastric ulcer surgery includes the use of:

- Soups made with vegetable broth or weak meat broth (exclude cabbage soup, okroshka and borscht). In soups, cereals are well boiled and vegetables are finely chopped. As before, to improve the taste, they add an egg-milk mixture, cream or butter.

- Dried wheat bread.

- Lean meat (beef, lamb, turkey, chicken) in the form of chopped, steamed products (meatballs, cutlets, pates, meatballs). Soft meat and boiled tongue can be eaten in pieces.

- Lean fish, chopped or in pieces, with the skin removed. You can eat jellied fish, but use vegetable broth for pouring.

- Milk, cream (in dishes), cottage cheese, non-acidic curdled milk and kefir. The choice of cottage cheese dishes is expanding - casseroles and lazy dumplings.

- Semolina, buckwheat and rice porridges are well boiled and have a semi-viscous consistency. They are prepared with water and the addition of milk.

- Butter and vegetable oil for prepared dishes.

- Mashed potatoes and puddings from potatoes, carrots, cauliflower and beets.

- Weak tea with milk, sweet fruit juices, jelly.

- Fruits only in heat-treated form (jelly, baked and pureed), compotes with pureed fruit.

Table of permitted products

| Proteins, g | Fats, g | Carbohydrates, g | Calories, kcal | |

Cereals and porridges | ||||

| buckwheat (kernel) | 12,6 | 3,3 | 62,1 | 313 |

| semolina | 10,3 | 1,0 | 73,3 | 328 |

| cereals | 11,9 | 7,2 | 69,3 | 366 |

| white rice | 6,7 | 0,7 | 78,9 | 344 |

Bakery products | ||||

| white bread crackers | 11,2 | 1,4 | 72,2 | 331 |

Confectionery | ||||

| jelly | 2,7 | 0,0 | 17,9 | 79 |

Raw materials and seasonings | ||||

| honey | 0,8 | 0,0 | 81,5 | 329 |

| sugar | 0,0 | 0,0 | 99,7 | 398 |

| milk sauce | 2,0 | 7,1 | 5,2 | 84 |

| sour cream sauce | 1,9 | 5,7 | 5,2 | 78 |

Dairy | ||||

| milk | 3,2 | 3,6 | 4,8 | 64 |

| cream | 2,8 | 20,0 | 3,7 | 205 |

Cheeses and cottage cheese | ||||

| cottage cheese | 17,2 | 5,0 | 1,8 | 121 |

Meat products | ||||

| boiled beef | 25,8 | 16,8 | 0,0 | 254 |

| boiled veal | 30,7 | 0,9 | 0,0 | 131 |

| rabbit | 21,0 | 8,0 | 0,0 | 156 |

Bird | ||||

| boiled chicken | 25,2 | 7,4 | 0,0 | 170 |

| turkey | 19,2 | 0,7 | 0,0 | 84 |

Eggs | ||||

| chicken eggs | 12,7 | 10,9 | 0,7 | 157 |

Oils and fats | ||||

| butter | 0,5 | 82,5 | 0,8 | 748 |

Non-alcoholic drinks | ||||

| mineral water | 0,0 | 0,0 | 0,0 | — |

| black tea with milk and sugar | 0,7 | 0,8 | 8,2 | 43 |

Juices and compotes | ||||

| juice | 0,3 | 0,1 | 9,2 | 40 |

| jelly | 0,2 | 0,0 | 16,7 | 68 |

| rose hip juice | 0,1 | 0,0 | 17,6 | 70 |

| * data is per 100 g of product | ||||

2. Reasons

With peptic ulcers of the stomach and/or duodenum, a certain seasonal dependence is most often observed, and most perforations occur in spring/autumn. It is also known that cases of perforated ulcers increase significantly during periods of socio-economic upheaval and military operations. In general, insufficient and unhealthy nutrition, especially in combination with chronic stress, is one of the main triggers of ulcerative perforation. There is no direct and clear dependence on age; patients include children and very elderly people, but statistically the age range of 25-50 years is considered to be the most risky.

The main risk factors include anything that sharply and quickly (or simultaneously) increases the pressure inside the stomach: blunt abdominal trauma, overeating, physical activity, drinking alcohol (especially fizzy drinks).

Visit our Gastroenterology page

Physiotherapy and types of procedures

The main techniques used for recovery after gastric surgery:

- galvanization - does not have a stimulating effect on the secretory function of the stomach, but at the same time helps to improve its bioelectrical activity. Which in turn improves blood circulation, normalizes the blood coagulation system, improves blood circulation in the liver, and has a beneficial effect on the immune system. If it is necessary to administer any drug, electrophoresis is prescribed.

- ultra-high frequency therapy (microwave) is a more deeply penetrating method of exposure to an electromagnetic field. It has the property of generating endogenous heat in tissues, which helps normalize a number of physiological reactions. Improves metabolic processes, blood microcirculation in tissues. But mainly, microwave helps to normalize the function of the thyroid gland and the endocrine system as a whole. In addition to restoring digestive functions after surgery, microwave helps stimulate reduced immunity and rapid healing of the postoperative scar.

- magnetic therapy - has analgesic, anti-inflammatory, trophic effects. But mainly it normalizes blood circulation, enhances the recovery process, and restores metabolism in the gastric mucosa.

Rehabilitation after gastric surgery, as we see, is not a quick process. And its peculiarity is that in addition to restoring the stomach itself, there is a need to restore many other organs and systems, as well as body functions. For example, such as digestion, endocrine regulation. Not only the above methods can be prescribed, but also many others.

It is also necessary to take into account that after surgery on the stomach, a person’s lifestyle may be completely different than before the operation. This mainly depends on the reason for which the operation was performed, as well as the type of operation performed. Depending on the complexity of the surgical intervention, a lot can change - from diet to loss of ability to work. Therefore, at certain stages of rehabilitation, psychological rehabilitation and medical and social control may be involved. And of course, some parts of rehabilitation need to be repeated periodically. Especially sanatorium-resort treatment and physiotherapy courses in the clinic at the place of residence.

3. Symptoms and diagnosis

In the clinic of a perforated ulcer, there are three stages, the names of which speak for themselves:

- abdominal shock;

- imaginary well-being;

- purulent diffuse peritonitis.

Each of these phases takes, on average, about six hours.

The most characteristic symptom of the initial stage is a sharp and very intense pain, often radiating to neighboring areas or the back. It is this type of pain syndrome that the well-known expression “dagger pain” refers to, and it, like a real sudden stab in the stomach, is accompanied by a powerful psycho-emotional shock. In most cases, the patient takes a forced fetal or other similar position, tries not to move (or rather, cannot), breathes shallowly and often, his eyes “sink,” his face acquires an earthy-pale hue and a characteristic motionless, suffering-panic expression. Bradycardia and a decrease in blood pressure, caused by a reflex reaction to damage to intra-abdominal tissues and receptors by the gushing acid of the gastric juice, are also quite typical.

Subsequently, the color of the facial skin, breathing, heart rate and blood pressure are somewhat normalized. At this stage, as a rule, precious time is lost: often the patient has to literally beg consent for a life-saving operation. Subjective improvement is not without reason called “imaginary well-being” - in fact, this is already a fatal risk, since in the next phase (repeated vomiting, dehydration, sharp worsening of the general condition, tachycardia and tachypnea, significant bloating) to provide assistance, even the most urgent and qualified, in many cases it is already too late.

An experienced doctor confidently assumes the diagnosis even with an external examination, palpation and percussion: there are a number of fairly informative criteria regarding muscle status, zones and nature of pain, etc.

However, much depends on the specific location of the perforation and the dynamics of symptoms. In some cases, the situation develops according to an atypical scenario; in particular, the clinical picture may resemble symptoms of acute appendicitis, myocardial infarction, pulmonary pathology - in other words, differentiation and clarification are required. In addition to the physical examination, laboratory tests, an X-ray examination (usually with a contrast agent, the detection of which outside the stomach and duodenum is one hundred percent proof of perforation), and urgent fibrogastroduodenoscopy are prescribed. In some diagnostically difficult cases, laparoscopic examination is used.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

Diet after surgery for perforated gastric ulcer

The first rule for recovery and reducing the risk of relapse is strict adherence to the doctor’s instructions. An exception to the rule “if you can’t, but really want to” doesn’t work. During the postoperative period, a strict diet is established. It can last from 3 to 6 months. The diet becomes more complex gradually.

Basic principles of the diet:

- The daily number of meals is up to 6 times, in small portions.

- All foods taken must be puree or semi-liquid.

- Food should be steamed or boiled

- Salt should be taken in limited quantities

- You should also limit your intake of simple carbohydrates (sugar, chocolate, baked goods) and liquids.

On the 2nd day after the operation, mineral water, fruit jelly, and weak, slightly sweetened tea are allowed.

After 2-3 days, the diet is replenished with rosehip decoction, pureed soups and porridges made from rice and buckwheat. Vegetable puree soups made from boiled carrots, pumpkin, zucchini, potatoes or beets. You are allowed to eat a soft-boiled egg and a steam soufflé made from pureed cottage cheese.

On the 10th day after the operation, puree from boiled carrots, pumpkin, zucchini or potatoes is introduced into the diet. Gradually introduce steamed cutlets, soufflés, purees, quenelles, meatballs or zrazy from lean meats or fish. They add cheesecakes, puddings, and cottage cheese casseroles. You can also use fresh pureed cottage cheese. In addition, whole milk and non-acidic dairy products (acidophilus, yogurt, matsoni) are introduced.

Only after a month does it become possible to consume bread products: dried bread, stale bread, crackers.

After 2 months, it is allowed to add fresh sour cream to food and consume kefir.

On this topic:

Diet for stomach ulcers - what can and cannot be eaten?

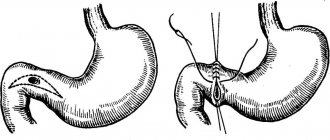

4.Treatment

Perforation of an ulcer is an absolute and unambiguous indication for emergency surgery. The techniques used (suturing, resection, etc.), antiseptic measures, postoperative treatment and rehabilitation strategies may be different, since the characteristics of a perforated ulcer vary widely and, in addition, the scale and stage of the process at the time of intervention is of key importance.

An important task is the prevention of complications - pneumonia, purulent inflammation, peristalsis disorders, etc.

It remains to add that even the constant skill of the domestic school of emergency surgery (and only the surgeons themselves truly know that in order to save a patient’s life in the operating room, only the surgeons themselves truly know), a perforated ulcer is characterized by a significant mortality rate (today this is 6-8%). The prognosis depends critically on the timeliness of seeking help and its provision, on the accuracy of diagnosis and the choice of the optimal surgical plan.

Panel: Risk factors predisposing to ulcer perforation

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (including aspirin)

Inhibitors of prostaglandin synthesis lead to increased gastric acid production and decreased mucus secretion.

Smoking

Smoking suppresses bicarbonate secretion. Nicotine stimulates acid secretion. Significantly associated with ulcer perforation in people under 75 years of age

Helicobacter pylori

It is most common in cohorts of young adults (usually <40 years of age) with perforated duodenum in low- and middle-income countries. Different virulence of strains may have a role in genesis.

Marginal ulcer after bariatric surgery

Probably associated with ischemia of the anastomosis.

Starvation

Perforation of ulcers has been reported during Ramadan. Fasting causes increased acid production when the stomach is empty.

Use of crack, cocaine and methamphetamine

May lead to severe vasoconstriction followed by ischemia. May also cause blood clots and mucosal necrosis.

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (gastrinoma)

Rarely; risk of formation of recurrent and multiple ulcers. Increased gastrin secretion causes increased secretion and persistence of hydrochloric acid in the stomach and duodenum, with ulceration and potential perforation of the gastrointestinal wall.

Stress ulcers

Occurs in patients in critical condition (burns, injuries, etc.) in the intensive care unit; most often complicated by bleeding, but sometimes perforate. Difficulty in diagnosing patients under the influence of sedatives or on mechanical ventilation.

Steroids

Affects the inflammatory cascade, including the synthesis of prostaglandins. They can dull the signs of peritonitis, blurring the picture and making it difficult to make a diagnosis.

Salt

Increased consumption increases the acidity of the stomach.

Prognostic factors and outcome prediction

No single factor readily identifies patients at high risk for a poor outcome, but older age, the presence of comorbidities, and diagnostic delay before surgery have been consistently associated with an increased risk of death. Clearly, identifying modifiable risk factors to potentially improve outcome is of great interest. In a systematic review covering more than 50 studies with 37 preoperative prognostic factors and including a total of 29,782 patients, several risk factors were consistently associated with mortality (Figure 3). Only two-thirds of studies reported estimates adjusted for risk factors. In addition, definitions and criteria for dividing (eg, age for defining the “elderly” group, creatinine level for diagnosing acute renal failure, and blood pressure for shock) were not consistent across studies. Thus, doctors have tried to combine risk factors to predict disease outcome.

Fig. 3. Preoperative prognostic factors unfavorable for the risk of mortality in perforated peptic ulcer disease

Unfavorable preoperative prognostic factors for mortality. Data taken from Moller et al. ASA - American Society of Anesthesiologists Risk Assessment Score.

Clinical prediction rules

Ideal clinical prediction rules must be easy to use, reliable, highly generalizable, and well validated both within and outside of a given study. However, the outcome prediction rules for ulcer perforation evaluated so far have not yet been classified as ideal.

Difficulties in defining a unified set of factors are likely related to their number and the overall complexity of the disease. Some factors considered are fixed (for example, patient age and gender), while others are adjustable (for example, time to treatment and resuscitation). In addition, given geographic differences in age, sex, and disease onset patterns, a universal, reproducible, and valid risk scoring system may be difficult to develop. The most widely used disease-specific prognostic score in patients with perforated ulcers is the Boey score, which is based on the presence of serious medical conditions, preoperative shock, and ulcer perforation more than 24 hours before surgery. However, its positive predictive value of 94% reported in early studies was not replicated in subsequent studies. Other prediction rules specifically for ulcer perforation have been proposed. However, none of these scoring systems have been validated in external cohorts, making their generalizability difficult. In addition, several different general surgical scoring systems and ICU scales have been used in patients with perforated ulcers. Again, the results were not uniformly confirmed over time and across cohorts, suggesting low external validity of these systems in this setting. It is clear that appropriate devices and studies are needed to analyze and compare data across regions to identify high-risk patients and to facilitate progress in research and experimental development.

Patient Management Strategies

Treatment of patients with perforated peptic ulcers should include early diagnosis and prompt initiation of resuscitation measures. A high short-term mortality rate associated with this disease is reported (10-30%), and morbidity and complications occur in 50-60% of patients. This means that a careful and structured therapeutic approach is required to improve results. There are several strategies and options available (Table 1), but the patient's condition should be taken into account when planning their use.

Preoperative preparation

Sepsis is often present in patients with perforated ulcers, being suspected in only 30-35% of patients presenting with sepsis on arrival to the operating room, and is a leading cause of death, accounting for 40-50% of deaths. Within 30 days after surgery, more than 25% of patients develop septic shock, leading to death in 50-60% of cases. Accordingly, a thorough history and measures to prevent, detect, and treat sepsis in patients with perforated ulcers may lead to a reduction in mortality and morbidity. This goal can be achieved by systematically assessing for signs of sepsis and treating patients according to the principles of the Surviving Sepsis Campaign, including fluid resuscitation, bacterial culture, empiric broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and resource management. A multidisciplinary preoperative approach based on these principles has been evaluated in non-randomized clinical trials in patients with complicated perforation peptic ulcer disease, with a statistically significant demonstrated reduction in mortality (number needed to treat per ten patients).

Conservative treatment

In patients with very few or localized symptoms who are in good clinical condition, the choice of surgery may be deliberately deferred in favor of a period of observation. The decision to forego immediate surgery for an initial attempt at a primary conservative strategy is not new and was first advocated more than half a century ago. In a number of consecutive samples, more than half of all patients with perforated ulcers experienced spontaneous obliteration, and such patients underwent successful conservative treatment. The strategy should include intravenous antibiotics, restriction of natural or nasogastric feeding, antisecretory and antacid medications (proton pump inhibitors), and imaging with water-soluble contrast to confirm perforation.

The only RCT ever conducted in this area (before the introduction of proton pump inhibitors) showed success of the conservative strategy in the majority of patients, but a high failure rate in older patients (aged > 70 years). However, when choosing a conservative treatment method, it must be taken into account that mortality from ulcer complications increases with every hour of delay before surgery.

Surgery

Delay of surgery was a factor consistently associated with mortality. Laparotomy with perforation closure using interrupted sutures with or without an omental pedicle to close the defect has been the main approach for several decades.

Laparoscopic repair of perforated ulcers is being used increasingly, recently reaching an incidence of 30-45% of cases. However, the use of laparoscopy varies around the world. A recent US study reported that less than 3% of patients with perforated peptic ulcers were operated on by laparoscopy. Two recent systematic reviews including three clinical RCTs found no difference in mortality or any clinically significant postoperative complications between open and laparoscopic surgery.

A review of the literature describing collected case series showed a small benefit of laparoscopy in reducing postoperative pain and length of hospital stay (and in some cases even reducing mortality), but the results of these reports may be biased towards selection of younger patients, favorable risk estimates (I - II according to the American Society of Anesthesiologists scale), small perforations (<10 mm), as well as short time periods from the onset of the disease to surgery. There is currently no evidence to suggest that laparoscopic surgery is better than open surgery, but there is no evidence that laparoscopy is harmful in patients with sepsis or widespread peritonitis. However, since no difference in mortality has been shown between these techniques, until there is reliable evidence of the superiority of one technique over another, its selection should be guided by the experience of the surgeons performing the operation and the assessment of the patient's condition. Sometimes the perforation may be too large (ie, >2 cm) or the inflamed tissue may be too friable to allow safe healing by primary intention. In addition, if the first attempt to close the defect fails, the second may also fail. In these circumstances, resection may be a safer option. It should be noted that large gastric ulcers or their persistent perforations should raise the suspicion of malignancy, which can be found in almost 30% of patients in this situation. Surgical strategy in such patients may then include resection (distal gastrectomy for gastric ulcer or formal gastrectomy for suspected malignancy), partial gastrectomy with diverting gastrojejunostomy (if the defects are located in the pyloric region) or placement of a T-tube drain, if the defect is in the duodenum. In Japan, some investigators have reported a higher proportion (up to 60%) of patients with perforated ulcers who underwent gastrectomy rather than primary suture, possibly based on tradition and the much higher incidence of gastric neoplasia in Japan. than in North America and Europe.

Table 1: Generalized view of the management of patients with ulcerative disease

| Comments | Base | |

| Prehospital, primary care | ||

| Definition of symptoms, high index of suspicion | Absence of peritonitis in a third of patients. There was no previous history of signs of peptic ulcer in almost half of the patients. Please note that symptoms may vary or be mild in older patients, obese individuals, immunocompromised individuals and children | Observational studies |

| Vital signs monitoring | Detect early signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) or sepsis by measuring blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature | Surviving Sepsis Campaign (see text) |

| Seek help as soon as possible | Quick connection to the emergency room or hospital. Every hour of delay increases the patient's risk of death | Observational studies |

| Emergency room | ||

| Diagnostics | Exclusively clinical in the presence of generalized peritonitis. Otherwise, CT => X-ray => Ultrasound. Determination of serum lipase to exclude the differential diagnosis of pancreatitis | Observational studies |

| Preparation | Stabilize according to sepsis management guidelines, but keep in mind to minimize surgical delay | Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| Screening for sepsis | Data allowing a conclusion about the diagnosis of sepsis | Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| Early intensive care | Prescribing infusion therapy, monitoring vital functions | Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| Early administration of antibiotics | Blood culture (x2); broad-spectrum antibiotics for intravenous administration | Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| Making decisions | ||

| Indications for surgery | Patient consent | Common sense |

| Conservative management | Used if: very limited symptoms/defect; the patient's unsuitability for surgery (eg, American Society of Anesthesiologists risk score 5); or the patient's reluctance. Assess the risks and suitability of postoperative intensive care; dialysis; ventilator support | One RCT on conservative treatment; case series; surveillance data with a high risk of discrepancy |

| Surgery | Open or laparoscopic (ready for conversion) (**alternatives to endoscopy) | 3 RCTs showing no difference in outcomes; experimental and sporadic data |

| Palliative care | If the patient is in the terminal stage of the disease | Optimal supportive care; expert opinions, no specific data; observation |

| Preoperative preparation | ||

| Cultures and biopsy | Peritoneal fluid smears, with or without tissue biopsy | Surviving Sepsis Campaign |

| Abbreviated laparotomy | If the patient is in severe shock | Case series |

| Intra-abdominal drainage | No data to support routine use | Observations |

| Postoperative management | ||

| Accelerated Recovery | Quick recovery is possible if the defect is small; providing food at the patient's request, early removal of drainage, early discharge | One small RCT with high risk of discrepancy |

| Helicobacter eradication | Esomeprazole 20 mg twice a day, or omeprazole 20 mg twice a day; amoxicillin 1 g twice a day; clarithromycin 500 mg twice daily | RCTs and meta-analyses |

| Observation (after discharge from the hospital) | Increased delayed mortality, possibly due to common risk factors such as smoking and comorbidities | Some observational studies |

| Control endoscopy | Rules out malignancy of a gastric ulcer if no preoperative biopsy was performed or if the location of the defect is not determined (malignancy of a duodenal ulcer is highly unlikely) | Expert opinions, observational studies |

*This column offers links and is not an exhaustive list. **Cm. Table 2, experimental nature

New treatment strategies for closing perforations

In recent years, new methods have often been used, in particular endoscopic ones. Some approaches represent an alternative between conservative and surgical treatment, such as endoscopic clamping or stenting, but are based on only a small case series (Table 2). Other innovations, such as the use of biodegradable material to cover the ulcer site or mesenchymal stem cells to improve wound healing, have only been evaluated experimentally and have not yet been tested in clinical trials.

Prevention of complications

The occurrence of early complications depends mainly on the quality of the operation performed and the skill of the surgeon. On the part of the patient, all that is required is strict adherence to the recommended diet, physical activity, etc.

To prevent late complications and make your life as easy as possible after surgery, you should follow the following recommendations:

- Be regularly examined by a gastroenterologist.

- Compliance with a fractional diet regimen for 6-8 months until the body adapts to new digestive conditions.

- Taking enzyme preparations in courses or “on demand”.

- Taking dietary supplements with iron and vitamins.

- Limiting heavy lifting for 2 months to prevent hernia.

According to reviews from patients who have undergone gastrectomy, the most difficult thing after surgery is to give up your eating habits and adapt to a new diet. But this must be done. Adaptation of the body to digestion in conditions of a shortened stomach lasts from 6 to 8 months, in some patients – up to a year.

Usually there is discomfort after eating and weight loss. It is very important to survive this period without any complications. After some time, the body adapts to the new condition, the symptoms of the operated stomach become less pronounced, and weight is restored. A person lives a normal, full life without part of the stomach.