Share information with your Facebook friends

VK

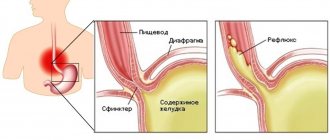

Laryngopharyngeal reflux belongs to the extraesophageal syndromes of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In this case, there is a reflux of stomach contents (acid, pepsin, bile acids) into the larynx and pharynx. Patients most often do not have the classic symptoms of GERD, and the most prominent complaints are: pain and/or burning in the throat, sore throat, chronic cough, dysphonia (voice disturbance), dysphagia (impaired swallowing), feeling of a lump or hair in the throat, etc. n. It is believed that up to 50% of patients with laryngeal and voice disorders have reflux. Most often, these manifestations of GERD are the result of so-called nocturnal reflux, when the patient is in a horizontal position for a long time, as well as due to excessive food intake at night. A diet for reflux is necessarily recommended for all patients suffering from GERD.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux

Summary. To this day, the problem of laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) remains very relevant. There is no clear definition, there is no single algorithm for its diagnosis and treatment. In this work, from a modern point of view, a definition of this disease is given, and existing diagnostic methods are carefully analyzed. The authors pay attention to the clinic of LPR, and mainly to changes in the ENT organs.

Definition of laryngopharyngeal reflux

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a violation of the peristalsis of the organs of the esophagogastroduodenal zone, with frequently repeated reflux of gastric or duodenal contents into the esophagus, with an increase in the exposure time of refluxate in the esophagus, leading to damage to the esophagus [1,2,3].

GERD is divided into 2 syndromes: esophageal and extraesophageal. Esophageal syndrome is manifested by functional disorders without damage to the esophagus and erosive esophagitis, Barrett's esophagus, esophageal adenocarcinoma, esophageal stricture [4]. Esophageal syndrome is characterized by the following typical symptoms of GERD: heartburn, chest pain, bleeding. When performing esophagogastroduodenoscopy, erosions, ulcers of the mucous membrane, strictures, and areas of metaplasia are detected [5,6,7]. Extraesophageal manifestations of GERD include reliably associated diseases: reflux cough, reflux laryngitis, reflux asthma, reflux caries, and unreliably associated diseases: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, pharyngitis, sinusitis, recurrent otitis media [8]. It is these patients that cause difficulties in the diagnosis and treatment of diseases, since the clinical picture of extraesophageal manifestations of GERD can manifest itself in different organs and concern doctors of different specialties (gastroenterologists, ENT doctors, dentists, therapists, cardiologists, pediatricians and pulmonologists). In addition, treatment outcomes for extraesophageal manifestations are worse than in patients who have changes in the esophagus [9]. It is known that of all extraesophageal manifestations of GERD, LPR is the most common [10, 11, 12]. The frequency of detection of ENT pathology in patients with GERD is 2 times higher than in the general population. The combination of GERD and ENT pathology is observed in up to 88.5% of cases [13]. The term LPR itself is not accurate, since there cannot be reflux from the larynx into the pharynx. It would be correct to use the name gastroesophagolaryngopharyngeal reflux. But this name (LFR) is a term recognized in the international medical literature, adopted for abbreviation and convenience. It was proposed by J. Koufman in 1991 [14], and since then it has firmly entered the arsenal of both gastroenterologists and foreign otorhinolaryngologists.

Currently, there is no accurate data in the literature on the prevalence of LPR, including in Russia, which is due to the difficulty of diagnosing it at an early stage, the lack of a “gold standard for diagnosis” and a clear algorithm for diagnosing this disease. The studies conducted on the prevalence of LPR were conducted at different times, most of them in only one region, and various criteria were used to confirm the diagnosis.

Population-based studies indicate that GERD is a common condition with a predominance in Western Europe and North America, accounting for 10–20% of the general population [8]. According to the University of Texas, LPR is detected in 50 million Americans, from 4 to 10% of people with GERD. But 20 to 70% of patients with LPR have esophageal symptoms of GERD [15]. There are publications that are based only on the analysis of one research method, for example, Merati AL and co-authors in a meta-analysis studied data from probe pH-metry readings in 264 patients; as a result of GERD and LPR, up to 60% of patients were diagnosed [16]. However, these data are difficult to consider reliable, because a correlation between clinical symptoms and pH-metry data was not established. This indicates that reflux can be detected in healthy individuals, but it can be one-time or its effect is not damaging due to well-functioning compensatory mechanisms of carbanhydrase.

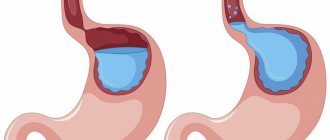

Etiology of laryngopharyngeal reflux One of the causes of GERD and LPR is a violation of the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract. The pathogenesis is based on: slower gastric emptying and decreased esophageal peristalsis; impaired relaxation and insufficient force of contraction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) against the background of episodes of increased intra-abdominal pressure; as well as the composition of the refluxate (acid, pepsin and bile), which can determine the severity of the disease [13, 17]. A large number of predisposing factors for the occurrence of GERD have been identified: hereditary predisposition, alcohol abuse, table salt, smoking, comorbid diseases (hiatal hernias, peptic ulcers, chronic gastritis and duodenitis, cholelithiasis, inflammatory bowel diseases), stress, flatulence, abdominal masses and retroperitoneal space, pregnancy, obesity. It has been found that GERD is more common in women than in men. It is possible that this predominance is due to the state of pregnancy, when the enlarged uterus puts pressure on other organs in the abdominal cavity. In most cases, GERD leads to the formation of LPR, however, there are also certain functional reasons (for example, insufficient tone of the upper esophageal sphincter (UPS)) and some behavioral characteristics, for example, overeating before bed, irregular eating, working in a bent position after eating , contributing to its occurrence. [18, 19] In addition, there is evidence in the literature that long-term use of antihypertensive drugs and antidepressants can lead to a decrease in the tone of the LES, or have a direct irritating or damaging effect on the mucous membranes of the upper digestive tract [20]. The esophagus is an actively peristaltic organ, which helps move the food bolus into the stomach. The contents of the stomach do not flow back into the esophagus and upper respiratory tract, since the UPS and LES are closed outside of food intake. Therefore, in healthy people, the pH level in the distal part of the esophagus is 6.0. During the reflux of acidic gastric contents into the esophagus, the pH in it decreases to 4.0, and when the alkaline contents of the duodenum (DU) are refluxed, it exceeds 7.0. The number of reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus should normally be no more than 50 during the day, and the total time of their occurrence should not exceed 1 hour. Normally, in all healthy people, a small amount of an enzyme is produced in the esophagus - carbanhydrase, which neutralizes hydrochloric acid that enters the esophagus during physiological reflux. Physiological reflux is a rare phenomenon, occurs after eating, has a short duration, never appears during sleep, and does not rise above the UPS. Pathological reflux is called if the time during which the pH in the esophagus reaches a level of 4.0 and below exceeds 5 minutes or lasts more than 4.5% of the total time of pH monitoring [21]. Reduced tone of the pharyngeal muscles contributes to the reflux of aggressive gastric contents from the esophagus into the pharynx, oral cavity and nasal cavity [22]. However, the basis for the occurrence of LPR is the dysfunction of the congenital heart, when gastric contents (hydrochloric acid and activated pepsin) are refluxed into the upper respiratory tract, including the larynx, damaging it. As a result, the reserves of isoenzyme III carbonic anhydrase are depleted and the secretion of bicarbonate ions by the laryngeal mucosa is reduced, mucociliary clearance is disrupted and an inflammatory process develops in the affected area [17].

Johnston N. et al note that the composition of the refluxate is important. In 20% of cases, the refluxate has an alkaline reaction, which demonstrates the presence of duodenogastric reflux. The authors indicate that pancreatic enzymes and bile acids have a more aggressive effect on the mucous membrane of the esophagus and upper respiratory tract [17].

Clinical presentation and diagnosis of laryngopharyngeal reflux Diagnosis of LPR is often difficult. LPR may be accompanied by obvious clinical manifestations of the gastrointestinal tract or be asymptomatic. Changes in ENT organs during LPR are varied, but still not fully understood. It has been proven that LPR causes reflux-induced laryngitis, benign and malignant neoplasms of the larynx, and laryngospasm [15, 23, 24, 25]. Some studies indicate that extraesophageal manifestations of GERD may be the cause of the development of chronic pharyngitis [26, 27], chronic otitis media [28], and chronic sinusitis [29]. However, there is no consensus on these issues yet, which confirms the need for further in-depth study of this relationship. [30,31]. Can LPR affect the lymphoid tissue of the pharynx? It probably can. Thus, a correlation has been established between hypertrophy of the pharyngeal tonsil, adenoiditis, and LPR [32]. It is possible that LPR may also affect the palatine tonsils. LPR can be suspected based on the following symptoms [33, 34]: an abundance of mucus in the oropharynx and hypopharynx; coating on the tongue; bleeding gums; aphthae; teeth marks on the tongue; discrepancy between the severity of complaints presented by the patient (for example, very severe pain in the throat and the pharyngoscopic picture; symptoms associated with unpleasant sensations in the ears that are not recorded objectively (from “popping” in the ears to ear congestion); discrepancy between the severity of symptoms from the larynx (hoarseness up to aphonia) and laryngoscopic picture; ineffectiveness of systemic antibiotic therapy for sore throat; excessive salivation, constant coughing, food “getting stuck” in the throat (spasm of the upper esophageal sphincter), sensation of a lump in the throat (globus sensation), pharyngeal paresthesia, sensation burning in the throat, difficulty swallowing saliva, appearing after eating [34].It is important to emphasize that today there is no “gold standard” for diagnosing LPR, since the diagnostic methods used, such as questionnaires, esophagogastroduadenoscopy (EGD), daily pH -metry, pharyngoscopy, laryngoscopy, chest radiography, pulmonary function testing, as well as lung scintigraphy, which allows one to detect reflux-induced microaspiration, have insufficient sensitivity and specificity [35].

For screening diagnostics of LPR, testing with the clinical questionnaire “Index of Reflux Symptoms (ISR)” adapted for use in Russian [34], which has shown high sensitivity and validity, is used. The questionnaire consists of 9 questions and includes a dynamic assessment of a number of indicators. Each IRS symptom is rated over the past month on a scale from 0 (no problems) to 5 (severe problems). A score of more than 13 correlates with a positive result of pH monitoring [34]. It is a self-administered tool that helps clinicians assess the clinical severity of LPR symptoms at the time of diagnosis and then track progress after treatment. This questionnaire can be used not only by a gastroenterologist, but also by an otorhinolaryngologist, dentist, cardiologist, pulmonologist, and all specialists who may encounter patients with extraesophageal manifestations of GERD in clinical practice.

Pharyngoscopy data are not specific: on the posterior and lateral walls of the pharynx, enlarged lymphoid follicles or hypertrophied mucous membrane, vascular injection and cyanotic color of the mucous membrane, mucous discharge between the anterior and posterior palatine arches and on the mucous membrane of the posterior pharyngeal wall can be detected [26] .

Signs of laryngeal damage detected during laryngoscopy: swelling and erythema of the mucous membrane of the posterior wall of the larynx, spreading to the arytenoid cartilages, interarytenoid spaces and often to the posterior third of the vocal cords, some time ago were considered clinical criteria for “reflux laryngitis”. Based on the obtained laryngoscopic data, a special scale of reflux signs (SRS) was proposed in 2001, designed to assess the effectiveness of treatment of laryngeal disorders caused by LPR [34]. Belafsky PC and co-authors made an attempt to translate qualitative signs of damage to the larynx during LPR, for example, erythema and swelling of the laryngeal mucosa, which are subjective and nonspecific, into quantitative ones. In total, researchers propose to evaluate 8 qualitative laryngoscopic signs of damage to the laryngeal mucosa with an overall assessment of their severity from 0 to 26 points [36, 37]. Some authors note that the use of the SRS is not a reliable scale for diagnosing LPR [38]. The main purpose of endoscopic laryngoscopy remains the diagnosis of neoplasms [39].

For a long time, ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring with two pH sensors was used to diagnose LPR both in Russia and abroad. The first sensor is installed at a distance of 5 cm above the LES, the second pH sensor is installed 5 cm below the LES to record LPR [40]. This method was considered the most sensitive test for diagnosing LPR, but since this disease does not have a laminar course, fluctuations in the process are constantly observed, negative pH-metry results cannot exclude LPR. Technical and financial difficulties have led to the limited use of this method in practical activities not only in Russia, but also abroad. At the moment, there is a more accurate and patient-friendly method for diagnosing LPR, which records naso- and oropharyngeal pH using a special Restech's Dx-pH measuring system. This system is capable of not only measuring, but also recording the slightest fluctuations in pH in the oral cavity and nasopharynx for two days every ½ s [41, 42]. However, this method for diagnosing LPR is expensive and cannot yet be used in routine practice.

Currently, there are no accurate digital data in the literature on the specificity and sensitivity of endoscopy as a method for diagnosing GERD and LPR. In the manuals on gastroenterology, the word “high” specificity and sensitivity is indicated instead of percentages. [21]. But endoscopy is recommended for diagnosing LPR by both domestic and foreign specialists [43]. When performing an endoscopy, it is possible to assess the condition of the mucous membrane of the esophagus, the obturator function of the cardiac sphincter (detection of insufficient closure of the cardia), the presence of a sliding hiatal hernia, and motor disorders. During EGD, it is possible to take a biopsy of the mucous membrane to verify metaplasia, visually determine the presence of ectopic foci of gastric epithelium in the proximal esophagus, assess the acidity of the stomach and esophagus, and screen for helicobacteriosis [21]. Currently, it has become possible to conduct endoscopy not only with the use of local anesthetics, but also under conditions of controlled sedation with propafol with parallel pH monitoring, which is not only more comfortable for the patient, but also improves the quality of the study results [44, 45].

Difficulties in diagnosing LPR may be associated not only with technical problems, but also with other reasons. In particular, the presence of combined pathologies in some cases does not allow us to understand the role of each in the development of the disease, for example, postnasal drip in hypertrophic rhinitis with a deviated nasal septum.

Therefore, empirical therapy with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) is used to determine the relationship between disease symptoms and reflux disease itself [35]. It is for this purpose that a readily available and simple pharmacological test with PPI has been developed and is used [46], which can replace 24-hour pH-metry and endoscopy. The essence of the test is that PPIs are powerful inhibitors of gastric acid, one of the main aggressive components of refluxate, which has an irritating effect on receptors located in the mucous membranes of the esophagus, respiratory tract, and oral cavity. Inhibition of the production of hydrochloric acid helps to increase intragastric pH, reduce pepsin activity, reduce receptor irritation and eliminate any manifestations of reflux. Initially, omeprazole was proposed as a test drug, and the test was called the “omeprazole test.” The test method consists of prescribing a standard dose of omeprazole (40 mg) once a day for 2 weeks.

The test is considered positive if, as a result of taking it, the manifestations of reflux decrease or disappear. The first assessment of the omeprazole test can be carried out on the 4th-5th day of administration. In recent years, another drug from the PPI group, rabeprazole at a dose of 20 mg per day, has been more often used instead of omeprazole. The use of the rabeprazole test makes it possible to reduce the testing time from 2 weeks to 7 days, and the first assessment to 1-3 days due to the faster onset of the maximum antisecretory effect of the drug. The specificity and sensitivity of the rabeprazole test are 86% and 78%, respectively. It has been proven that in terms of diagnostic value, this PPI test is not inferior to 24-hour pH monitoring and endoscopic examination of the esophagus and is even considered equivalent to them. This test is of particular value in patients with LPR and esophageal manifestations of GERD with concomitant pathology. A positive test is the basis for treatment of all manifestations of GERD, including LPR, using PPIs as basic drugs [46, 47]. However, PPI monotherapy has not been shown to be effective compared with placebo in controlled studies. Over the past decades, 2 large meta-analyses [48,49] and 8 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [50, 51,52,53,54,55,56,57] were conducted in which more than 15 thousand patients were examined, and in the study Both adults and children took part, the results of which concluded that in the treatment of GERD, including LPR, PPI is ineffective and there is a pronounced placebo effect, and that the effectiveness of long-term use of PPI in such patients has not been identified [48 , 55, 56, 58]. But most of these studies had relatively varied sample sizes, ranging from 62 to 7,188 people. In addition, the inclusion criteria for patients in the study were inadequate. Thus, both adults and children with various forms of GERD, including LPR, could take part in the same study. PPI dosage was variable: from 20 to 80 mg as a single dose. The frequency of taking the drug also varied: from 1 to 2-3 during the day. The duration of treatment varied from 1 month to 2-3 months. There were also no uniform criteria for both diagnosing LPR and monitoring the dynamics of treatment. Thus, almost none of the studies used the ISR questionnaire to diagnose symptoms of LPR. In most cases, researchers assessed symptoms using self-developed questionnaires, which lack evidence of specificity and sensitivity, raising doubts about their validity. In addition, the ineffectiveness of PPI monotherapy is most likely due to the presence of not only hydrochloric acid, but also pepsin in the gastric contents. Saritas Yuksel E. and co-authors in 2012 conducted a blinded, prospective, controlled study to determine pesin in saliva in patients with GERD. The study included 58 patients with GERD, whose diagnosis was made on the basis of endoscopy and pH measurements. Special test strips were used to detect pepsin. During the study, pepsin was detected in the saliva of the majority of patients with GERD; the authors concluded that the immunological test for determining pepsin in saliva in patients with GERD is highly sensitive (87%) and specific (87%), and can replace expensive invasive techniques diagnostics [59]. It is possible that the use of this technique for screening LPR is very promising. In Russia, this technique is not yet used due to the lack of certified test systems.

Treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux

To date, there is no single document that would reflect the basic approach to the treatment of LPR. This is due to the fact that there is no consensus on which specialty doctors should diagnose and treat LPR, this extra-esophageal manifestation of GERD, as well as the mixed results of the treatment regimens used.

Over the past few years, 2 approaches to the treatment of LPR have emerged. The first approach involves guiding the patient along the path of lifestyle modification and the use of PPIs in the form of monotherapy. So there is short-term empirical treatment with standard doses of PPIs (20-40 mg). Lifestyle modification includes the following measures: frequent small meals, weight loss, normalization of sleep patterns, raising the head of the bed, quitting smoking. These simple actions on the part of the patient, according to DL Steward et al [60], over a period of 2 months, significantly reduce symptoms, followed by transition to maintenance therapy for 6-12 months. This treatment regimen is considered “generally accepted” throughout the world by both otolaryngologists and gastroenterologists [61, 62]. However, the effectiveness of its use, as well as the dosage, frequency and duration of taking the drug are still being discussed. The ineffectiveness of PPI monotherapy is most likely due to the presence of non-acid reflux, when the main damaging agent is pepsin, bile acids, pancreatic enzymes, and not hydrochloric acid [63]. In some patients, double doses of PPIs (40–80 mg) are used when standard doses are ineffective, since acid reflux persists in approximately 50% of patients with persistent esophagitis or reflux symptoms [64,65]. Dose selection is determined on an individual basis [62, 66]. But still, in case of combined pathology, PPIs are included in the complex therapy of the underlying disease (for example, bronchial asthma, coronary heart disease, obesity), which greatly facilitates the course of the underlying pathology.

Due to the ineffectiveness of PPIs as monotherapy, a second comprehensive approach has been proposed in most cases. Some authors prefer the use of PPIs and prokinetics [25], others prefer the use of PPIs and antacids or alginates [43]. Russian specialists use a triple treatment regimen for the treatment of GERD, including extraesophageal manifestations: PPIs (omesaprazole, esomeprazole, pantoprazole), prokinetics (Ganaton) and antacids or alginates (Gaviscon) [67, 68]. The use of several drugs in the treatment of LPR is more justified from the point of view of the etiopathogenesis of the disease. Treatment of LPR can be not only medicinal, but also surgical. The operation of choice is laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication [60]. The essence of the operation is that the fundus of the stomach is wrapped around the lower part of the esophagus, thereby forming a cuff that prevents the backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus [70].

- Indications for surgery for GERD and LPR according to the clinical guidelines of the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons are:

- -lack of physical ability to take medications;

- -intolerance to drugs used to treat LPR;

- - severe manifestations of LPR and other extraesophageal manifestations such as aspiration, asthma or cough;

- -ulcerative strictures of the esophagus;

- - hiatal hernia, gastric cardia insufficiency;

- -abnormal non-acid reflux in PPI-resistant patients. [71].

This operation is performed only in stationary conditions. After surgery, the patient stays in the clinic for 1 to 3 days [72]. Thus, the problem of LPR is very relevant. Damage to ENT organs during LPR requires a more detailed study. Often patients with LPR complain of a sore throat, an unpleasant taste in the mouth after brushing their teeth, and the formation of caseous plugs in the tonsils. An ENT examination in this group of patients reveals caseous plugs in the lacunae of the palatine tonsils. The patients are functional and active, but their quality of life is reduced. Taking antibiotics and performing instrumental washing of the lacunae of the palatine tonsils with antiseptic solutions turns out to be ineffective, and in some cases lead to a worsening of the disease (caseous plugs form faster and in larger quantities). Why is this happening?

Can this lesion of the palatine tonsils (only caseous plugs in the lacunae of the palatine tonsils) against the background of LPR be attributed to a simple form of chronic tonsillitis? Could LPR be one of the causes of damage to the tonsils? If this is so, then this group of patients needs treatment, but of a completely different nature, since caseous plugs in the lacunae of the palatine tonsils are one of the manifestations of LPR.

The role of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the course of chronic pharyngitis

Many works are devoted to the issues of diagnosis, clinical course and treatment of chronic pharyngitis. Most of them describe new methods of examination and treatment. However, the number of patients with chronic pharyngitis at appointments with ENT doctors is not decreasing.

Chronic pharyngitis is a common polyetiological disease characterized by inflammatory-dystrophic changes in the mucous membrane of the posterior pharyngeal wall [4].

Depending on the pathomorphological changes, catarrhal, hypertrophic, subatrophic and atrophic pharyngitis are distinguished. A mixed form of chronic pharyngitis is often found.

Patients with chronic pharyngitis complain of a sore, tickling sensation in the throat, increased salivation, which necessitates frequent coughing and expectoration of accumulated contents. At the same time, dryness in the throat, a feeling of incomplete swallowing of food, and the “lump symptom” may be disturbing [6].

The disease is painful for patients. Patients repeatedly seek medical help from various specialists and undergo multiple courses of treatment. However, most of them never receive real help and are left alone with their problems.

Many domestic and foreign works have studied in detail the influence of waste products of various microorganisms and viruses on the mucous membrane of the oropharynx. However, this etiological factor is not the root cause of the disease, i.e. the occurrence of chronic pharyngitis depends not so much on the nature and virulence of the microorganism, but on the degree of disruption of the biochemical processes of both the mucous membrane and the body as a whole [4].

According to A.Yu. Ovchinnikov, chronic pharyngitis in most cases is a disease of a non-infectious nature, since the qualitative and quantitative composition of the microflora sown from the mucous membrane of the pharynx in patients with chronic pharyngitis differs little from that in persons with normal condition of the mucous membrane of the oropharynx [5].

The true causes of the disease are far from understood. Obviously, further work and the introduction of new modern views and research methods into clinical practice are necessary.

An equally important and common problem is chronic cough. About a third of patients seeking medical help complain of chronic cough.

Physiologically, coughing is a protective reflex aimed at removing excess secretions, dust or smoke from the respiratory tract. This is a quick strong exhalation, as a result of which the tracheobronchial tree is cleared of foreign bodies [8, 9].

According to the Richard S. Irvin classification of 2000, acute cough is considered to be a cough lasting no more than three weeks (most often against the background of an acute viral infection), subacute cough lasting more than three but less than eight weeks, chronic cough more than eight weeks [8, 9] .

Despite the fact that cough is often associated in patients with pathology of the bronchopulmonary system, it can occur in a number of diseases, varied in their pathogenesis and location of damage [4].

Richard S. Irvin in 1990 conducted a prospective study of the causes of chronic cough. As a result, several diseases were identified that are characterized by chronic cough. Of those examined, 54% were diagnosed with postnasal drip syndrome, 31% had bronchial hyperreactivity, 28% had gastroesophageal reflux, 7% had chronic bronchitis, 12% had other causes of cough, and In almost 10% the cause could not be determined. Moreover, almost a quarter of those examined had two causes of cough, and 3% had three causes.

Currently, the problem of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and its extraesophageal manifestations has increasingly begun to be raised at world gastroenterological forums. Interest in this problem is not accidental. Foreign colleagues have identified and are actively studying the relationship between the pathology of the upper respiratory tract and gastroesophageal reflux.

The term GERD is used by most clinicians and researchers to denote a chronic relapsing disease caused by spontaneous, regularly recurring retrograde entry of gastric and/or duodenal contents into the esophagus, leading to damage to the distal esophagus and/or the appearance of characteristic symptoms (heartburn, retrosternal pain, dysphagia) [7, 3, 2], which basically allow one to suspect GERD in a patient. However, in some patients the disease has less typical manifestations - reflux-associated cardiac, pulmonary and ENT organs. They are often underestimated, especially in the absence of specific symptoms of GERD, which can lead to underdiagnosis and incorrect patient management tactics.

According to the International Classification of Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease adopted in Montreal in 2006, chronic pharyngitis is one of the presumed extra-esophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. There is currently no substantiated evidence of this relationship.

The purpose of the work is to develop an algorithm for the examination and treatment of patients with chronic pharyngitis, to evaluate the effectiveness of antireflux therapy in the treatment of chronic pharyngitis.

The patients we observed were examined before the start of treatment, as well as during the treatment process. Immediate results were assessed no earlier than two months after the start of therapy directly by the patients themselves (who were offered a specially designed questionnaire), as well as using the above objective methods.

In the course of the study for the period 2005-2006. We examined 37 patients with chronic pharyngitis aged from 19 to 70 years who applied for a consultation at the Moscow Regional Clinical Hospital. Among them there were 14 men, 23 women. 17 patients suffered from chronic subatrophic pharyngitis, chronic catarrhal pharyngitis occurred in 11 people, hypertrophic pharyngitis in 9. The patients were divided into three groups; the first group consisted of 16 patients who were diagnosed with GERD with high gastroesophageal reflux , the second group was 8 patients with GERD without high pathological reflux, the third group was 13 patients in whom there was no evidence of GERD based on the results of 24-hour pH monitoring. Thus, among the patients with chronic pharyngitis we examined, 24 people suffered from GERD (Tables 1, 2).

In our study, in seven patients we observed reflux-esophagitis grade A, in two - grade B. At the same time, one patient with reflux-esophagitis grade B had high alkaline reflux. Among our patients there was not a single one with reflux esophagitis of degrees C and D.

Our study revealed pH fluctuations from 2.0 to 8.5 at the level of the upper third of the esophagus.

After 24-hour pH monitoring when the diagnosis of GERD was made, antireflux therapy was included in the standard treatment of chronic pharyngitis. Therapy was carried out for at least two months. During therapy, there is a significant improvement in the course of chronic pharyngitis, as well as in 24-hour pH monitoring data, while numerous courses of standard treatment for chronic pharyngitis for these patients turn out to be ineffective.

Preliminary results allow us to judge the significant pathogenetic role of GERD in the development and course of pharyngitis. In this regard, we believe that:

- patients under the supervision of an otorhinolaryngologist with a diagnosis of chronic pharyngitis should be consulted by a gastroenterologist.

- all patients with chronic pharyngitis require fibroesophagogastroduodenoscopy

- If endoscopic signs characteristic of GERD are detected, daily high pH-metry is indicated

- 24-hour pH measurements should be performed in patients who clinically do not respond to standard therapy for chronic pharyngitis, regardless of the presence of complaints characteristic of GERD and endoscopic findings in the esophagus.

D.M. Mustafaev, Z.M. Ashurov, V.A. Isakov, V.G. Zenger, S.V. Morozov, S.G. Tereshchenko, V.L. Shabarov, N.G. Lyubimova, A.S. Epanchintseva, L.V. Gibadullina.

Moscow Regional Scientific Research Clinical Institute named after. M.F. Vladimirsky, Moscow (director - senior doctor of sciences of the Russian Federation, corresponding member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, professor G.A. Onoprienko)

Acute laryngitis - symptoms and treatment

The larynx (Larynx) is a conventional boundary separating the upper and lower respiratory tract. This is a kind of musical instrument in the human body that gives voice. It is built on the principle of a movement apparatus - it contains a skeleton (cartilages of the larynx) and its connections (ligaments and joints). This frame has two bands of muscle (vocal cords) that run along the top of the windpipe (trachea). The movements and vibrations of these muscles allow us to speak, sing and whisper.

In addition to the voice-forming function, the larynx also performs a protective function. When we swallow, the larynx closes its opening so that food and liquids enter the esophagus rather than the airways [4].

Regardless of the cause, inflammation causes swelling of the vocal cords and narrowing of the space between them. Protein breakdown occurs, which leads to an increase in osmotic and oncotic pressure in damaged tissues. Due to the difference in pressure, fluid rushes into the damaged area, which leads to the appearance of edema. Changes appear in the mucous membrane of the larynx:

- Catarrhal (associated with inflammation of the mucous membranes): hypersecretion of the mucous glands, swelling, redness. Observed during viral infections.

- Severe swelling - with allergies.

- Infiltrative (accumulation of cells mixed with blood and lymph in the tissues of the body) - characteristic of neoplasms and chemical lesions (when exposed to acids, alkalis and other caustic liquids);

- Purulent - for bacterial infections [5].

In response to irritants, the mucous membrane of the larynx begins to produce mucus, which can also clog the respiratory lumen, like a plug. Mucus is produced by special cells called goblet cells. They are located in the mucous membrane and submucosal glands. Mucus serves to protect epithelial cells from infectious agents, allergens and irritants. This is why smokers suffer from a constant cough with sputum production. Increased mucus secretion in the respiratory tract is a marker of many common diseases, such as acute respiratory viral infections or allergies.

Due to swelling of the mucous membrane, the vocal cords thicken and cannot vibrate, the voice changes, becomes hoarse or disappears altogether. In severe cases, the ligaments can practically close, causing shortness of breath and noisy, hoarse breathing due to the inability to take a breath. This condition is called laryngeal stenosis, another name is false croup (from the Scottish “croup” - to croak). This life-threatening condition, which is characterized by a barking cough, is often accompanied by inspiratory dyspnea (difficulty breathing) and hoarseness of the voice. Usually observed in children aged 6-36 months, most often against the background of a viral infection: parainfluenza - 50%, influenza - 23%, adenovirus infection - 21%, rhinovirus infection - 5% [6].