Introduction

Unlike achalasia cardia, in the pathogenesis of which the main role belongs to disturbances in the innervation of the esophagus and increased sensitivity of the sphincter to gastrin, achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter is a consequence of dysfunctions of the complex neuromuscular apparatus that ensures the act of swallowing [8, 19, 24].

Achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter most often has a central origin and occurs due to the death of brain stem structures, such as the double nucleus, nuclei of the IX, X, XII pairs of cranial nerves (acute cerebrovascular accident, Parkinson's disease, neuroinfection, surgical intervention in these areas) [9, 11, 15, 17, 18, 25].

Much less common is achalasia of peripheral origin as a consequence of impaired innervation of the pharyngeal muscles (after laryngectomy).

Achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter should be differentiated from Plummer-Vinson syndrome in iron deficiency anemia, from globus hystericus in young women with neurasthenia, from transient symptoms during menorrhagia, during menopause [23, 25].

A sharp violation of the act of swallowing (dysphagia) or its complete impossibility (phagia) is a painful suffering that sharply worsens the quality of life.

Attempts to swallow water, food and even saliva lead to their release through the nose and into the lumen of the trachea. As a result of choking on saliva and food, repeated outbreaks of aspiration pneumonia occur. If such patients survive, they are doomed to be fed through a gastric tube, and then, with the inevitable addition of esophagitis and esophageal strictures, to be fed through a gastrostomy tube.

The mechanism of aphagia of central origin is the lack of relaxation of the cricopharyngeus muscle at the moment of passage of the food bolus from the pharynx into the esophagus. This muscle, first discovered by Valsalva in 1717, is the only antagonist muscle in the complex neuromuscular apparatus of the pharyngoesophageal junction. The concept of the pharyngoesophageal junction is associated with the names of J. Terracol [27] and N. Brandenburg [10]. The study of the pathophysiological aspects of a large group of diseases accompanied by dysfunction of the pharyngoesophageal junction began in the late 60s of the 20th century [4, 8, 13, 17], although the first attempts at surgical treatment of dysphagia were made by L. Rogers [22] in 1935. (bilateral sympathetic cervical denervation) and C. Kaplan [20] in 1951 (transection of the cricopharyngeus muscle for dysphagia due to poliomyelitis).

At the same time, as rightly noted by R. Mason et al. [21], “These disorders have been dealt with by various medical specialists (gastroenterologists, otorhinolaryngologists, general and thoracic surgeons), which still brings ... confusion to the concept of the essence of suffering.” Unfortunately, in the domestic medical literature, publications on this problem are rare [1—4, 6, 7].

In the National Guidelines for Radiation Diagnostics and Therapy (2014), there is no mention of this disease in the sections “Functional disorders of the esophagus” and “Achalasia of the esophagus.” They are not included in surgical manuals either.

Abroad, quite a lot of experience has been accumulated in the surgical treatment of achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter, using the technique of P. Chodoch [13], who in 1975 published a detailed description of the technique of longitudinal myotomy - a simple operation that returns the majority of patients to the possibility of natural nutrition through the mouth.

The purpose of the work is to present the experience of diagnosis and surgical treatment of achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter.

Material and methods

The first operation in Russia (USSR) on a patient with Zakharchenko-Wallenberg syndrome (phagia, ataxia) due to cerebrovascular accident in the brain stem area was performed by us at the Research Institute of Emergency Medicine named after. N.V. Sklifosovsky on April 4, 1984. This patient with a good result of the operation was demonstrated at the 2229th meeting of the Moscow Surgical Society on September 25, 1986.

From 1984 to 2014 at the Research Institute of Emergency Medicine named after. N.V. Sklifosovsky hospitalized 32 patients aged from 24 to 83 years. There were 24 men, 8 women. The cause of dysphagia in 29 patients was cerebrovascular accident, 1 had Parkinson’s disease, 1 had undergone laryngectomy, and 1 had dysphagia of a psychogenic nature.

Duration of swallowing disorders before admission to the Research Institute of Emergency Medicine named after. N.V. Sklifosovsky ranged from 4 weeks to 2 years.

Surgical treatment was carried out in 28 cases: in 7 of them extramucosal myotomy was performed according to P. Chodoch, in 21 - myotomy with plastic surgery of the pharyngoesophageal junction according to the author’s technique.

4 patients were not operated on. Of these, 2 patients, transferred from other hospitals in extremely serious condition due to bilateral aspiration abscess pneumonia, died in the intensive care unit without surgery. In one patient who was admitted early, complex conservative treatment, including stimulation of the pharyngeal muscles, led to partial restoration of swallowing, and he was discharged without surgery. Another patient suffered from psychogenic dysphagia as a result of anaphylactic shock and, after correction of the disorders, was also discharged for outpatient treatment.

To examine patients, clinical, radiological, endoscopic methods and pharyngoesophagomanometry were used.

A thorough assessment of the neurological status, visual monitoring of the function of the epiglottis and the tone of the pharyngeal muscles, as our experience has shown, are the determining criteria for selecting patients for surgical treatment.

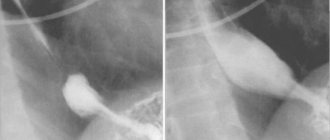

The X-ray examination consisted of a contrast study of the pharynx and esophagus in two projections. Due to the risk of aspiration, the study was performed while attempting to swallow a small amount of water-soluble contrast agent. The results of the study were recorded on X-ray film, and video recording was performed in 20 observations. When analyzing the video material, the absence of contrast agent entry into the esophagus (Fig. 1, a) and its pendulum-like movement in the oropharynx with reflux into the trachea and bronchi were clearly noted.

Rice. 1. Radiographs of a patient with achalasia of the upper esophageal sphincter. a - before surgery. The contrast agent does not enter the esophagus (1 - straight, 2 - lateral projection); b — 1 month after surgery. Free flow of contrast agent into the esophagus (1 - straight, 2 - lateral projection).

Pharyngoesophagoscopy was performed to assess the condition of the piriform sinuses, muscle tone of the laryngopharynx and identify concomitant diseases. During endoscopic examination, some resistance to the advancement of the endoscope in the area of the entrance to the esophagus was noted. All patients had concomitant diseases: cardial failure (5 observations), axial cardiac hiatal hernia (24), reflux esophagitis of varying severity (16).

Pharyngoesophagomanometry was performed in 18 cases. Intracavitary pressure was recorded using the open catheter method [5, 12, 14]. Pharyngoesophageal manometry yielded conflicting data: baseline pressure in the area of the upper esophageal sphincter was increased in 10 patients and decreased in 8 patients. Perhaps these data were due to the difficulties of accurately fixing the sensors during the study of patients who had suffered cerebrovascular accidents. The amplitude of the first positive wave and the amplitude of sphincter opening to swallow were also reduced or absent, which was consistent with clinical and radiological examinations and did not provide additional information on the basis of which treatment tactics could be determined.

Surgery

In the first 2 patients operated on in 1984, we used a simple dissection of the cricopharyngeal muscle according to the method of P. Chodoch. However, if in the first observation we obtained an excellent result, then in the second the effect was insignificant. It should be emphasized that, according to the literature [16], good results of cricopharyngeal myotomy are observed in 64% of patients.

The disadvantage of extramucosal myotomy, in our opinion, is that the dissection of the spasmodic (and after a certain time - scarred) muscle, eliminating the mechanical obstacle in the area of the pharyngoesophageal junction, leaves the entrance to the esophagus closed, which makes it difficult for the weakened food bolus to move forward muscles of the pharynx. In such cases, a large swallow of a dense bolus of food quickly passes into the esophagus, while small sips of liquid remain in the mouth and the patient is forced to spit them out.

In this regard, we developed (author's certificate No. 1551999 dated 09/01/89) and used in clinical practice in 21 patients an extramucosal plastic myotomy with movement of the fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor.

The technique of the operation was as follows. A longitudinal incision along the anterior edge of the left sternocleidomastoid muscle was used to widely expose the left and posterior walls of the pharynx, the wall of the initial esophagus and the prevertebral fascia, paying attention to the preservation of the recurrent nerve.

The cricopharyngeal muscle in patients with achalasia was visualized in the form of a transversely located, spasmodic whitish roller 4-6 mm wide at the border between the oblique fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor and the longitudinal muscles of the esophagus. Inspection of the intervention area and subsequent manipulations are facilitated by the presence of a thick gastric tube in the lumen of the pharynx and esophagus.

Two suture threads were placed on the cricopharyngeus muscle along the posterior left wall; by pulling them, a dissector was brought under the muscle cushion and the muscle was crossed between the holders without opening the mucous membrane.

To ensure the intersection of all fibers of this muscle, the incision was extended upward to the muscles of the pharynx by 1 cm and downward to the muscular layer of the esophagus by 3-4 cm (Fig. 2, a). Next, two sutures made of non-absorbable material (2/0) on an atraumatic needle were used to fix the posterior edge of the transected cricopharyngeus muscle to the prevertebral fascia (see Fig. 2, b).

Rice. 2. Scheme of the stages of plastic cricopharyngeal myotomy. 1 - pharyngeal constrictor; 2 - cricopharyngeal muscle; 3 - esophagus; 4 - prevertebral fascia; 5 — fixing seams; 6 — thread-holder. Other explanations are in the text.

Opposite these sutures, a thread-holder was placed on the anterior edge of the transected muscle, pulling which turned the slit-like defect into a triangular one, carefully peeling off the muscles of the pharynx and esophagus from the submucosal layer with a tight tupper. The superiorly adjacent and obliquely located fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor, running from anterior to posterior and upward, moved horizontally. In this position, they were fixed with separate sutures to the anterior edge of the transected cricopharyngeal muscle, which ensured at the moment of swallowing (with the posterior edge of the muscle fixed to the prevertebral fascia) traction of the wall forward and opening the entrance to the esophagus.

The remaining defect in the posterior left wall of the pharyngoesophageal junction was sutured with rare sutures in order to prevent the formation of a pulsion diverticulum in this area (see Fig. 2, c).

In 5 elderly and senile patients with severe concomitant diseases and consequences of acute cerebrovascular accident with aphagia, we had to limit ourselves to myotomy according to P. Chodoch under local anesthesia as it was simpler and faster.

Pathological reflux

The mechanism of pathological reflux The main factor necessary for the occurrence of GERD is gastroesophageal reflux, which occurs in the area of the transition of the esophagus to the stomach. Functional activity in this area is determined by both anatomical and physiological features: the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, external pressure on the lower esophageal sphincter from the muscle bundles of the diaphragm, the location of the lower esophageal sphincter in the abdominal cavity, the existence of a valve that acts as a valve in the area between the final part esophagus and the initial part of the stomach. The lower esophageal sphincter is a ring of muscle located at the junction of the esophagus and the stomach. The tone of the lower esophageal sphincter is its muscle tension, due to which the lumen of the esophagus in this area is blocked and the access of stomach contents (including gastric juice) into the esophagus is stopped.

Most likely, the viability of antireflux protection of the esophagus is determined by the combination of these features. Moreover, the main mechanism that protects against the occurrence of pathological gastroesophageal reflux may change under the influence of physiological causes. For example, the location of part of the lower esophageal sphincter in the abdominal cavity may play an important role in preventing the occurrence of reflux during swallowing; external pressure from the diaphragm can serve as protection against increased intra-abdominal pressure; the initial tone of the lower esophageal sphincter prevents reflux during rest in a horizontal position. If these protective mechanisms are disrupted, the frequency of reflux and the pathological effect of acidic contents on the esophagus increases.

During the research, three main mechanisms of dysfunction in the area of the transition of the esophagus to the stomach were identified:

- spontaneously (from time to time) relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter in the absence of anatomical abnormalities; — weakening of the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter in the absence of anatomical abnormalities; - anatomical curvature in the area of the esophagogastric junction, in particular due to a hiatal hernia.

Some studies suggest that when spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter increases, moderate GERD develops, whereas when there is a hiatal hernia or weakened lower esophageal sphincter tone, more severe cases occur.

Spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter It has now been proven that spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter is the most common cause of gastroesophageal reflux in patients with normal sphincter tone. Compared to the physiological relaxation of the sphincter during swallowing, spontaneous relaxation occurs regardless of the act of swallowing, is not accompanied by the phenomena of esophageal peristalsis and the action of the diaphragm, and lasts longer (more than 10 seconds).

When the lower esophageal sphincter spontaneously relaxes in patients with GERD, reflux of acidic gastric contents occurs more often than gas. The importance of spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter for the occurrence of reflux is confirmed by the use of physiological manipulations or drugs that influence this mechanism.

Decreased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter Physiologically, the lower esophageal sphincter is a 3-4 cm section located at the esophagogastric junction and containing muscle tissue capable of contractions. The resting pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter region varies from 10 to 30 mm Hg in different people. Art., depending on the pressure inside the stomach. Long-term measurements of pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter region show significant variability over time. In addition, sphincter tone is affected by intra-abdominal pressure, gastric distension, hormone levels, various foods and many medications. Both its own muscle structures and influence from the nervous system (mainly from the vagus nerve) are responsible for maintaining the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter.

GERD develops when pressure in the area of the lower esophageal sphincter decreases due to both tense and free reflux. Tense reflux occurs when, due to decreased tone, the sphincter opens at the moment of a sharp increase in intra-abdominal pressure (when coughing, sneezing, straining). Free reflux occurs only when there is a sharp decrease in pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter compared to intragastric pressure. It should be noted that a large number of people with GERD experience either intense or free reflux when the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter periodically decreases due to certain foods, medications, or habits.

Hiatus Hernia and Other Anatomical Causes Research in physiology in the 1980s has shown that there are two hypotheses to explain how the form and function of the esophagogastric junction are maintained: with the help of the intrinsic muscle fibers of the lower esophageal sphincter and with the help of mechanical support of the sphincter from the diaphragm side. The latter manifests itself during dilatation of the esophagus, vomiting and belching, and occurs under the control of the nervous system. On the other hand, contraction of the diaphragm muscles prevents pressure from the abdominal cavity during straining or coughing (conditions that increase intra-abdominal pressure).

The clinical significance of the role of external pressure in the area of the esophagogastric junction becomes clear in the presence of pathology on the part of the diaphragm - a hiatal hernia. Patients with this type of hernia experience progressive deterioration of function in the area where the esophagus enters the stomach, the part where the hernia is present. This occurs because in the presence of a hernia, the muscular part of the diaphragm, which normally ensures the normal functioning of the lower esophageal sphincter due to external pressure, moves away from it, which leads to a decrease in the tone of the sphincter.

On the other hand, the presence of a hiatal hernia impairs the antireflux protection of the esophagus by reducing the pressure inside the esophagogastric junction. A hernia reduces the length of the esophagogastric junction at the lower esophageal sphincter.

In addition, a hiatal hernia predisposes to the development of gastroesophageal reflux by increasing the frequency of spontaneous relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter, which causes the reflux of acid from the stomach. Although spontaneous relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter in patients with hiatal hernia occurs somewhat more often, the main factor contributing to the reflux of acid into the esophagus in these patients is reflux during relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter during the act of swallowing during the period of decreased sphincter tone with increased pressure in the abdominal cavity or without it.

Causes and predisposing factors

- Obesity. - Incorrect posture, stooping. - Persistent cough. - Constipation (which causes an increase in intra-abdominal pressure when straining during defecation). - Hereditary predisposition. - Smoking. — Congenital developmental defects. — Types of hiatal hernia:

Sliding hiatal hernia. Occurs when the connection between the esophagus and stomach moves upward through the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm as intra-abdominal pressure increases. When the pressure in the abdominal cavity returns to normal, the stomach descends to its usual place in the abdominal cavity. Fixed hiatal hernia. In this case, such displacement as with a sliding hernia does not occur, that is, part of the stomach is always located in the chest cavity above its normal location.

Symptoms:

It should be noted that for many people, a hiatal hernia itself does not manifest itself in any way.

Possible symptoms:

- Chest pain, including pressing. - Heartburn. — Difficulty swallowing – dysphagia. - Cough. - Belching. - Frequent attacks of hiccups. - Pain. It can be felt not only in the chest, but also in the stomach. Occurs when the stomach moves into the chest cavity through the narrow esophageal opening of the diaphragm.

Intense pain can be caused by the development of a complication of a fixed hiatal hernia, when the blood supply to the part of the stomach that is located in the chest cavity is disrupted (strangulated hiatal hernia).

Diagnostics:

The symptoms of a hiatal hernia are similar to those of heart disease. Therefore, especially at the first visit, the doctor conducts an examination to exclude the presence of heart disease. In addition, the doctor usually gives recommendations on lifestyle changes and measures that will allow you to independently relieve certain symptoms.

A complete examination includes examination of the respiratory, cardiovascular and digestive systems.

Basic examination methods:

— Electrocardiography (ECG) to exclude heart disease. - Chest X-ray to rule out the presence of pneumonia or other lung diseases that can cause similar symptoms. — Blood test (helps detect or exclude the presence of anemia, infection or diseases of the heart, pancreas, liver). — Other methods of studying the respiratory and cardiovascular systems if necessary.

Additional examination methods:

— X-ray contrast study with barium of the upper digestive tract. — Endoscopic examination (with a biopsy if necessary) to exclude the presence of esophageal ulcers or tumors.

Disease prognosis:

With adequate treatment and lifestyle changes, the symptoms of a hiatal hernia can be minimized.

Complications:

Incarcerated hiatal hernia.

When a hernia and reflux disease are combined, other complications may also occur:

Bleeding. Perforation of the esophagus. High risk of developing esophageal cancer. Self-help measures:

Lifestyle changes:

Try to avoid carrying heavy objects and physical stress. Don't slouch, especially when sitting. Try to move more, do gymnastics. Try to lose weight. Raise the head of the bed by 10-15 cm (place something under the legs of the bed). After eating, try to walk around, do not sit and, especially, do not lie down. Changing your diet and routine:

Avoid: caffeine-containing drinks, chocolate, fatty and fried foods, foods containing peppermint, alcohol. Have your last meal 2-3 hours before bedtime. Eat more often, but in smaller portions. Over-the-counter drugs:

Before taking these medications yourself, consult your doctor; be sure to tell him if you are pregnant or if you have concomitant diseases.

If an attack of pain or sudden onset of other symptoms occurs, take one of the following antacids: Maalox, Almagel, De-Nol. To prevent symptoms, you can take Zantac, ranitidine, Quamatel, or other H2 blockers for a while. Basic treatment:

The main treatment for hiatal hernia includes taking proton pump inhibitors (Omez, Pariet, Nexium, etc.). Sometimes surgical treatment is necessary, especially when there is a risk of developing a strangulated hernia. In the most difficult cases, when all measures are ineffective, a major operation is required. When should you see a doctor:

If any new symptoms appear. If the symptoms of the disease continue for a long time or are severe. When immediate assistance and hospitalization are required

If you experience severe chest pain, including pressing, especially if you have comorbidities such as diabetes, high blood pressure, or if you smoke, you are over 55 years old, you are a man, you have high cholesterol levels, there is a family history of there were cases of heart disease. Vomiting with blood. Dark, tarry stools. Palpitations (a feeling that the heart is beating faster than usual). Cough and fever. Shortness of breath (difficulty breathing). Difficulty swallowing solid foods or liquids. Retention of food masses in the stomach Retention of food masses in the stomach (that is, a slowdown in the process of moving food from the stomach further into the intestines) can contribute to the development of GERD, as it is accompanied by stretching of the stomach, which can cause: 1) an increase in the pressure difference between the stomach and the esophagus; 2) an increase in the volume of the stomach and, accordingly, the volume of stomach contents that can potentially enter the esophagus; 3) increase in the frequency of spontaneous relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter; 4) increased acid production in the stomach. That is, when the stomach is stretched, its contents are “squeezed out” into the esophagus.

However, only some patients with GERD actually experience retention of food in the stomach, while others do not experience this problem. Considering that patients with functional insufficiency of the stomach's ability to contract do not have concomitant esophagitis, we can conclude that, most likely, the retention of food mass in the stomach is only one of the possible risk factors for the development of GERD, and not its direct cause.

Esophageal clearance After the reflux of acidic contents from the stomach into the esophagus, a certain time is necessary to clear the esophagus of acid (esophageal clearance). This time while the esophageal mucosa is exposed to acid is called esophageal clearance time.

Esophageal clearance begins with peristalsis (muscle contractions in a certain direction, in this case towards the stomach), of the esophagus, with the help of which the esophagus is released from the acid that has entered there due to reflux. Clearance is completed by diluting the remaining acid with ingested saliva. The entry of saliva from the mouth into the esophagus improves esophageal clearance and, to a greater extent than peristalsis, helps restore normal acidity (pH) in the esophagus. It takes about 7 ml of saliva to neutralize 1 ml of hydrochloric acid; half of the neutralization occurs due to bicarbonate (a substance with an alkaline reaction) contained in saliva. The normal salivary flow rate is 0.5 ml/min. Thus, normally, substances that enhance salivation (lozenges or lozenges, chewing gum, etc.) accelerate esophageal clearance, while reduced salivation or replacing saliva with an equivalent amount of water slows down the clearance of acid from the esophagus. During sleep, salivation practically stops, but due to the production of bicarbonate by the glands of the esophageal mucosa, esophageal clearance still continues to some extent.

An increase in the duration of esophageal clearance (delayed clearing of acid from the esophagus) in patients with esophagitis is detected using a special test. Studies have found that only half of patients with GERD have prolonged esophageal clearance. When conducting studies with pH monitoring (see below), it was found that this is due to the presence of a hiatal hernia in some patients, which is accompanied by a tendency to lengthen esophageal clearance. Data from clinical studies have also shown that prolongation of esophageal clearance correlates with the severity of esophagitis and the presence of Barrett's esophagus.

Today, two main reasons for the lengthening of esophageal clearance are known: retention of food masses in the esophagus and deterioration of salivary function.

Retention of food masses in the esophagus

The assumption that the deterioration of evacuation of the contents of the esophagus plays a role in the development of reflux disease arose from the fact that the condition of patients improves with changes in body position, when in an upright position the contents of the esophagus more easily pass into the stomach under the influence of gravity. Two main mechanisms have been identified for delaying the passage of esophageal contents into the stomach: impaired peristalsis and reverse reflux associated with non-reducible hiatal hernia.

Some studies have been devoted to disturbances in esophageal peristalsis, which have shown that a significant weakening of peristalsis leads to retention of food masses in the esophagus. A mechanism was identified called ineffective esophageal contraction, in which more than 30% of esophageal muscle contractions had significantly reduced force. This theory was also confirmed by an analysis of the results of treatment of esophagitis, which showed in some cases the lack of effect from the use of therapy aimed at reducing acidity and from surgical treatment.

The presence of a hiatal hernia also leads to retention of food masses in the esophagus. A study of the acidity of the esophagus, as well as other instrumental studies, showed that the deterioration of esophageal clearance was caused by the reflux of contents from the pocket formed by the hernia during the act of swallowing.

Function of the salivary glands

The final phase of esophageal clearance is associated with salivation. Just as retention of food masses in the esophagus increases the time of esophageal clearance, the same happens when the production of saliva, which neutralizes acid, decreases. For example, decreased saliva production during sleep causes transient reflux either during sleep or just before sleep, which is accompanied by a significant prolongation of esophageal clearance. Long-term xerostomia (a condition of dry mouth caused by insufficient salivation) contributes to prolonged exposure to acid in the esophagus and, as a result, the development of esophagitis. However, studies have not noted a clear relationship between impaired salivary function and the occurrence of GERD when comparing sick people with healthy people.

It should be borne in mind that bicarbonates found in saliva contain so-called growth factors - substances that promote faster restoration of the esophageal mucosa after damage. However, according to research, it is still impossible to draw a clear conclusion that changes in the amount of these substances play an important role in the development of GERD.

Tissue resistance and factors contributing to their damage. Tissue resistance is resistance to various pathological agents that contribute to their damage. The mucous membrane of the esophagus has such resistance, which is provided by certain cellular and physiological components that protect it from the pathological effects of acid. The epithelium of the mucous membrane performs a protective function both in itself, due to the thickness of the tissue and the ability to recover (regenerate), and due to the presence of glands that produce bicarbonates, which neutralize the effect of acid.

Although most of the facts known about GERD indicate that the disease develops mainly due to impaired motility of the esophagus, it is nevertheless clear that the acidic contents of the stomach damage the lining of the esophagus, and the longer the exposure to acid, the more severe the damage . Moreover, according to research, the strength of this damaging effect does not depend on the quality and quantity of acid produced in the stomach and the enzyme pepsin (another damaging agent that enters the esophagus during reflux).

Although the main agents that damage the cells of the esophageal mucosa are hydrogen ions (contained in hydrochloric acid), substances contained in gastric juice such as pepsin, bile, and substances that are part of the food consumed also play a role in the development of GERD.

The role of duodenal contents (particularly bile) in damage to the esophageal mucosa is probably small and occurs in patients who have undergone surgery to remove part of the stomach (partial gastrectomy). However, damage to the mucous membrane of the esophagus occurs to a greater extent when reflux of gastric juice is combined with duodenogastric reflux (reflux of the contents of the duodenum into the stomach and then into the esophagus). That is, the mutual effect of stomach acid and bile on the mucous membrane of the esophagus can most likely be compared with the combined effect of acid and pepsin.

So, we have looked at the main causes and mechanism of development of reflux disease. The implementation of these mechanisms is facilitated by the following predisposing factors:

Lifestyle: alcohol abuse; smoking; incorrect posture (stooping). Taking certain medications: calcium channel blockers (verapamil, amlodipine, diltiazem, cordafen); drugs containing theophylline (teopek, theotard); nitrates (nitroglycerin, nitrosorbide); antihistamines (suprastin, fenkarol). Errors in the diet: eating fatty and fried foods; chocolate; onions and garlic; caffeinated drinks (coffee, black tea, Coca-Cola); products containing a large amount of acids (citrus fruits, tomatoes); spicy food. Eating habits: eating large portions; eating shortly before bedtime. Associated conditions: presence of hiatal hernia; pregnancy; diabetes; rapid weight gain. Pregnancy very often predisposes to the development of GERD - 50-80% of pregnant women complain of heartburn. As the uterus enlarges, intra-abdominal pressure increases, which contributes to the occurrence of reflux. In addition, during pregnancy, the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter decreases, and food stays in the stomach longer. This appears to happen because pregnancy increases the production of certain hormones. Scleroderma (a connective tissue disease) also often contributes to the development of GERD. This is due to impaired esophageal peristalsis and decreased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. Such disorders are not specific to scleroderma and can develop with any connective tissue disease. Chagren's syndrome, a rare disorder characterized by decreased salivary production, predisposes to the development of GERD due to increased duration of esophageal clearance and is a risk factor for the development of esophagitis. Thus, conditions in which either the protective (antireflux) barrier is disrupted or the duration of esophageal clearance is increased predispose to the development of GERD. An exception is Solinger-Ellison syndrome, in which the decisive role is played by the quantity and composition of the contents thrown into the esophagus.

SIGN UP FOR A CONSULTATION by phone +7 (812) 921 - 7 - 921