A pancreatic cyst is a cavity that is surrounded by a capsule and filled with fluid. The most common morphological form of cystic lesions of the pancreas are postnecrotic cysts. At the Yusupov Hospital, doctors identify cysts in the pancreas through the use of modern instrumental diagnostic methods: ultrasound, retrograde cholangiopancreatography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT). Patients are examined using the latest diagnostic equipment from leading global manufacturers.

The increase in the number of patients with cystic lesions of the pancreas is facilitated by the indomitable increase in the incidence of acute and chronic pancreatitis, the increase in the number of destructive and complicated forms of the disease. The frequency of postnecrotic pancreatic cysts is increasing due to the introduction of effective methods of conservative treatment of acute and chronic pancreatitis.

Against the backdrop of intensive therapy, therapists at the Yusupov Hospital are increasingly able to stop the process of destruction and reduce the frequency of purulent-septic complications. Surgeons use innovative techniques for treating pancreatic cysts. Severe cases of the disease are discussed at a meeting of the Expert Council with the participation of professors and doctors of the highest category. Leading surgeons collectively decide on patient management tactics.

Kinds

Congenital (dysontogenetic) pancreatic cysts are formed as a result of malformations of the tissue of the organ and its ductal system. Acquired pancreatic cysts are as follows:

- Retention - develop as a result of narrowing of the excretory ducts of the gland, persistent blockage of their lumen by neoplasms and stones;

- Degenerative – formed as a result of damage to gland tissue during pancreatic necrosis, tumor process, hemorrhage;

- Proliferative – cavitary neoplasms, which include cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas;

- Parasitic - echinococcal, cysticercosis.

Depending on the cause of the disease, pancreatic cysts of an alcoholic nature and those developing as a result of cholelithiasis are distinguished. With the increasing number of terrorist acts, road traffic accidents, natural and man-made disasters, the formation of false pancreatic cysts in severe abdominal injuries is becoming important. Depending on the location of the cystic formation, a cyst of the head, body or tail of the pancreas is distinguished.

True cysts make up 20% of cystic formations of the pancreas. True cysts include:

- Congenital dysontogenetic cysts of the gland;

- Acquired retention cysts;

- Cystadenomas and cystadenocarcinomas.

A distinctive feature of a true cyst is the presence of an epithelial lining on its inner surface. True cysts, unlike false formations, usually do not reach large sizes and are often accidental findings during surgery.

A false cyst is observed in 80% of all pancreatic cysts. It forms after trauma to the pancreas or acute destructive pancreatitis, which was accompanied by focal tissue necrosis, destruction of the walls of the ducts, hemorrhages and release of pancreatic juice outside the gland. The walls of the false cyst are compacted peritoneum and fibrous tissue; from the inside they do not have an epithelial lining, but are represented by granulation tissue. The cavity of a false cyst is usually filled with necrotic tissue and fluid. Its contents are serous or purulent exudate, which contains a large admixture of clots of altered blood and spilled pancreatic juice. A false cyst can be located in the head, body and tail of the pancreas and reach large sizes. It contains 1-2 liters of content.

Among cystic formations of the pancreas, surgeons distinguish the following main types, which differ in the mechanisms and causes of formation, features of the clinical picture and morphology required in the application of surgical tactics:

- Extrapancreatic false cysts occur due to pancreatic necrosis or trauma to the pancreas. They can occupy the entire omental bursa, the left and right hypochondrium, and are sometimes located in other parts of the chest and abdominal cavities, the retroperitoneal space;

- Intrapancreatic false cysts are usually a complication of recurrent focal pancreatic necrosis. They are smaller in size, often located in the head of the pancreas and often communicate with its ductal system;

- Cystic dilatation of the pancreatic ducts as their dropsy is most often found in alcoholic calculous pancreatitis;

- Retention cysts most often originate from the distal parts of the pancreas, have thin walls and are not fused with the surrounding tissues;

- Multiple thin-walled cysts unchanged in the remaining parts of the pancreas.

Make an appointment

Classification of pancreatic injuries

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) Pancreatic Injury Severity Scale (OIS) is the most widely accepted grading system for pancreatic injuries (Table 1).

Table 1. AAST OIS (American Association for the Surgery of Trauma) pancreatic injury score.

At the same time, the OIS scoring system describes pancreatic injury in terms of anatomical location and ductal involvement, but does not take into account the patient's condition, which has a high predictive value for clinical outcome. Krige et al published a pancreatic injury mortality score (PIMS) (Table 2), which takes into account variables such as: age > 55 years; shock on admission, extent of pancreatic injury and comorbidities. Ductal injury cannot be visualized on MSCT but can be inferred based on the depth of the pancreatic parenchymal tear.

Table 2. PIMS scale

Interpretation: - 0–4 points - low risk of death; — 5–9 points — average risk of death; — 10 or more points — high risk of death.

The modified CT pancreatic injury grading proposed by Wong et al (Table 3) is another system used to determine ductal injury. This assessment is based on the presence or absence of pancreatic tears, the location of the tears, and the depth of the tears. Class A injuries describe a rupture involving less than 50% of the thickness of the pancreas, usually without injury to the duct; Class B and C injuries occur to the left or right of the superior mesenteric artery, respectively, involve more than 50% of the thickness of the pancreas and are usually accompanied by damage to the duct.

Table 3. CT classification of pancreatic injuries

Stages

The process of formation of a post-acrotic cyst of the pancreas goes through 4 stages. At the first stage of the appearance of a cyst, a cavity is formed in the omental bursa, filled with exudate due to acute pancreatitis. This stage lasts 1.5-2 months. The second stage is the beginning of capsule formation. A loose capsule appears around the unformed pseudocyst. Necrotic tissue with polynuclear infiltration remains on the inner surface. The duration of the second stage is 2-3 months from the moment of occurrence.

At the third stage, the formation of the fibrous capsule of the pseudocyst, firmly fused with the surrounding tissues, is completed. The inflammatory process is intense. It is productive. Due to phagocytosis, the liberation of the cyst from necrotic tissue and decay products is completed. The duration of this stage varies from 6 to 12 months.

The fourth stage is the isolation of the cyst. Only a year later, the processes of destruction of the adhesions between the wall of the pseudocyst and the surrounding tissues begin. This is facilitated by the constant peristaltic movement of organs that are fused with a fixed cyst, and the long-term effect of proteolytic enzymes on scar adhesions. The cyst becomes mobile and is easily separated from the surrounding tissue.

Symptoms and diagnosis

The clinical signs of a pancreatic cyst are determined by the underlying disease against which it arose, the presence of the cyst itself, and the complications that arise. A small cyst may be asymptomatic. In acute and chronic pancreatitis, during the next relapse of the disease, doctors at the Yusupov Hospital identify a slightly painful round formation in the projection area of the pancreas, which may suggest a gland cyst. The most often asymptomatic cysts are congenital cysts, retention cysts and small cystadenomas.

Pain, depending on the size of the cyst and the degree of pressure it exerts on neighboring organs and nerve formations, on the solar plexus and nerve nodes along large vessels, can be of the following nature:

- Paroxysmal, in the form of colic;

- Encircling;

- Dumb.

With severe pain, the patient sometimes takes a forced knee-elbow position, lies on the right or left side, and stands leaning forward. The pain caused by the cyst is often assessed by patients as a feeling of heaviness or pressure in the epigastric region, which intensifies after eating.

More severe pain accompanies the acute form of the cyst in the initial phase of its formation. They are a consequence of pancreatitis of traumatic or inflammatory origin and progressive proteolytic breakdown of gland tissue. A tumor-like formation that can be felt in the epigastric region is the most reliable sign of a pancreatic cyst. Sometimes it appears and disappears again. This is due to periodic emptying of the cyst cavity into the pancreatic duct.

More rare signs of a pancreatic cyst include the following symptoms:

- Nausea;

- Belching;

- Diarrhea;

- Temperature increase;

- Weight loss;

- Weakness;

- Jaundice;

- Itchy skin;

- Ascites (accumulation of fluid in the abdomen).

The presence of a shadow, the position of which corresponds to the boundaries of the cyst, can sometimes be determined on a plain radiograph of the abdominal cavity. The contours of the cyst are most reliably revealed during duodenography in a state of artificial hypotension. Cysts of the body and tail of the gland often deform the contour of the stomach on an x-ray. The round filling defect that forms in this case allows one to suspect a cyst. Large, descending cysts are sometimes detected during irrigoscopy.

Pancreatic cysts are well contoured during angiography of the branches of the celiac artery. Doctors at the Yusupov Hospital obtain valuable data for making a diagnosis with retropneumoperitoneum and pneumoperitoneum in combination with urography. Determining the level of pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase) in the blood and urine is of some importance for establishing an accurate diagnosis. Violations of the secretory function of the pancreas are very rare with cysts.

Pancreatic cysts often lead to complications, which are manifested mainly by compression of various organs: the stomach, duodenum and other parts of the intestine, kidneys and ureter, portal vein, bile ducts. When a pancreatic cyst ruptures, inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) develops. When carrying out differential diagnosis, doctors at the Yusupov Hospital exclude tumors and cysts of the liver, various types of splenomegaly, hydronephrosis and kidney neoplasms, tumors and cysts of the retroperitoneum, mesentery of the ovary, encysted ulcers of the abdominal cavity and aortic aneurysm.

In this lecture we will discuss a rather rare type of injury due to closed abdominal trauma. Pancreatic injury (PPI) occurs in only 0.2-1% of patients with closed trauma [1-3] and in 3.1% of patients with closed abdominal trauma [4]. PPV appears to be more common in children, but this lecture, like the previous and subsequent ones, is devoted to the surgery of lesions in adults.

According to D. Dahiya et al. [5], PPV is in fourth place in frequency after damage to the liver, spleen and kidneys. The small number of victims with PPC limits the possibility of developing evidence-based recommendations [6]. To increase the level of evidence, some scientists combine victims with closed and open trauma into one group, but the authors consider this study design to be erroneous.

PPV occurs when an organ is compressed between a blunt hard object and the spine, as well as from a direct blow to the epigastric and hypochondrial region [7-10].

The most common cause of life-threatening injuries in Europe and developing countries is road traffic accidents [2, 11-14]. According to forensic autopsies, among the causes of death of victims with PPV, road traffic accidents were in first place, railway accidents were in second place, and catatrauma was in third place [15].

Features of the topographic anatomy of the pancreas (PG) determine its isolated damage in a smaller number of victims [16-18].

There are several classifications of life expectancy, which are given in chronological order (Tables 1, 2, 2, 3, 4, 5).

Table 1. Classification of pancreatic injuries by C. Lucas (1977, cited from [19]) Note. pancreas - pancreas; Duodenum - duodenum.

Table 2. Classification of pancreatic injuries by D. Smego [20]

Table 3. Classification of pancreatic injuries The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma [21] Note. Add one grade for multiple pancreatic injuries, but not more than grade III; * — the distal part of the pancreas is located to the right of the superior mesenteric vein; ** — the proximal part of the pancreas is located to the left of the superior mesenteric vein.

Table 4. Classification of pancreatic injuries by C. Frey and J. Wardell (cited from [22])

Table 5. Classification of pancreatic injuries T. Takishima [24] Note. PP - pancreatic duct.

In the classification of A.K. Eramishantsev and A.B. Molitvoslovova [23] included contusion of the pancreas with the formation of a non-tensioned subcapsular hematoma without damage to the capsule; pancreatic rupture or crush without damage to the main pancreatic duct; rupture of the pancreas or its crushing with damage to the main pancreatic duct; combined pancreaticoduodenal injury.

For the reader who would like to get acquainted with the classification of life expectancy in more detail, we invite you to read the article by G. Oniscu et al. [22].

I-II degree of injury according to OIS occurs in 41.8-68.8% of victims, III-V - in 31.3-58.2% [18, 25]. In the head of the pancreas, the rupture is located in 19.1-40%, in the isthmus - in 14.3-43.6%, in the body - in 14.3-23.6%, in the tail - in 23.6-31.4 % of victims [15, 25].

Timely diagnosis of PPC allows early initiation of adequate conservative treatment or surgery, and a delay in treatment increases the incidence of complications and adverse outcomes [26-30].

Symptoms of PPV are nonspecific and are often masked by injury to other organs, making the clinical diagnosis of this condition difficult [31]. If the patient undergoes an emergency laparotomy, then the diagnosis of prostate cancer is reduced to a full examination of the abdominal organs and retroperitoneal space [32]. Typical mistakes, such as avoiding revision of the omental bursa and refusal to mobilize the pancreas, lead to the fact that the pancreas is undiagnosed even during laparotomy.

Isolated PPV is not easy to establish before laparotomy. According to A. Leppäniemi and R. Haapiainen [33], risk factors for late diagnosis of PPV are closed injury, intoxication upon admission, low injury severity index (New Injury Severity Score [34] or Abdominal Trauma Index [35]), absence of injuries to other abdominal organs and conservative treatment of the victim.

In the clinical diagnosis of PPG, G. Jurkovich and C. Carrico [36] advise paying attention to trauma to the upper abdomen, a classic example of which is a blow to the steering wheel of a car or a bicycle handlebar, to traces of trauma to the upper half of the abdomen, a fracture of the lower ribs or costal arch. Pain in the epigastric region that does not correspond to findings on clinical examination is also a warning sign.

The role of amylasemia in the diagnosis of PPC is unclear. D. Potoka et al. [19] believe that this indicator does not have sufficient sensitivity and specificity. It should be emphasized that hyperamylasemia occurs no earlier than 3 hours after injury. Increased amylase levels, according to K. Xie et al. [3], noted in 86% of victims with PPV and in all victims observed by L. Kaman et al. [12]. These works indicate a fairly high sensitivity of amylasemia, but what specificity does this test have? An increase in the level of amylase and lipase is determined in cases of rupture of the duodenum and jejunum in some victims who are in shock or require massive blood transfusion [37], in victims with severe traumatic brain injury [38]. The work [39], which included its own research and systematic analysis of the literature, proved that a simultaneous increase in serum amylase and lipase levels has 100% specificity and 85% sensitivity in diagnosing PPC. The authors point out that an increase in the level of these enzymes occurs no earlier than 6 hours after injury, and recommend the use of these studies in the absence of instrumental diagnostic methods.

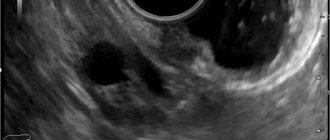

The retroperitoneal location of the pancreas makes laparocentesis and peritoneal lavage uninformative for diagnosing the pancreas in the early stages after injury. Ultrasound examination (US) is considered as a method for diagnosing PPC in a few studies [40, 41]. The FAST protocol, which is most often used in emergency situations, does not include pancreatic examination at all. Ultrasound of the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal space in the diagnosis of PPC is characterized by low sensitivity (44.4%, according to M. Sato and H. Yoshii [42]). It is possible that contrast-enhanced ultrasound will have greater diagnostic accuracy, but such work has only just begun to appear [43, 44].

Computed tomography (CT), which is the main method of non-invasive diagnostics for abdominal trauma, does not have the same high accuracy in relation to the prostate gland as in relation to other parenchymal organs. Direct computed tomographic signs of pancreatic cancer include intense bleeding from the pancreas, its hematoma or rupture, local or diffuse enlargement of the organ or its swelling, and reduced accumulation of contrast agent. Indirect signs of PPC include fluid accumulations in the retroperitoneum, swelling of the parapancreatic tissue, thickening of the anterior layer of the renal fascia, inflammatory changes in the parapancreatic tissue or mesentery, fluid in the omental bursa, near the transverse colon, superior mesenteric artery or splenic vein, free fluid in the abdominal cavity [45-47]. Not all signs allow us to establish the degree of PPV; many of them are nonspecific [48], but they force us to continue the examination.

It should be noted that the use of multislice tomographs has made it possible to significantly improve the diagnosis of the RA and, most importantly, the diagnosis of RA damage. From 1998 to the present, the sensitivity of CT in diagnosing RA has increased from 33.3% [31, 49] to 78.9-91.7% [50, 51], and in diagnosing RA damage - from 52.4 to 91 % [51, 52]. The specificity of diagnosing PPC is currently 90.3-98.4% [46]. The best visualization of RA damage is possible in the portal phase of the study [53, 54].

Concluding the section on computed tomographic diagnosis of the pancreas, the lecturers consider it necessary to express the opinion that the presence of signs of pancreatic injury is an indication for other examination methods - magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP). J. Duchesne et al. [55] share the same point of view. Signs of RA damage identified by CT are an indication for surgery - endoscopic (stenting) or open. The absence of signs of pancreatic injury allows continued conservative therapy.

MRCP is a non-invasive and accurate method for diagnosing pancreatic rupture [47, 56], but it is not often used in patients with abdominal trauma. The sensitivity of MRCP in diagnosing RA was 92.8%, and in diagnosing RA rupture - 91.7% [51].

The use of ERCP, given its diagnostic role [57] and therapeutic possibilities for rupture of the RA, seems very attractive [58–61]. Therapeutic measures may include nasopancreatic drainage or transpapillary stenting of the RA [59, 62]. Unfortunately, the severity of the general condition of the victim, the difficulties of diagnosis and the lack of a sufficiently experienced doctor lead to the fact that ERCP is often performed in the long term due to post-traumatic complications [63-66].

To diagnose the pancreas, video laparoscopy is sometimes used, which makes it possible to exclude ongoing intra-abdominal bleeding, examine the anterior surface of the pancreas and drain the omental bursa and abdominal cavity [3, 67].

We consider it necessary to emphasize that the reference points for choosing a treatment method are the presence or absence of a rupture of the pancreatic duct and its localization - the distal or proximal part of the organ. The basis for this conclusion was the work of R. Heitsch and D. Smego [20, 68]. When choosing a treatment method, it is also necessary to take into account the general severity of the victim’s condition, the experience of the surgeon and endoscopist, and the technical equipment of the hospital.

If the patient is indicated for emergency laparotomy, for example due to intra-abdominal bleeding, then adequate exploration of the pancreas is the key to a successful diagnosis. Revision of P.Zh. indicated in the presence of trauma to the organs of the upper abdominal cavity - liver, spleen, stomach and duodenum. Central-medial retroperitoneal hemorrhage (located cranial to the root of the mesentery of the transverse colon), blood clots in the omental bursa, edema or bile leakage around the duodenum are indications for a thorough revision of the pancreas.

To examine the head and isthmus, it is necessary to mobilize the duodenum according to Kocher; simultaneous mobilization of the right flexure of the colon allows for improved visualization and provides bimanual palpation of the head, isthmus and uncinate process. Inspection of the anterior surface of the body and tail of the pancreas is usually carried out through the dissected gastrocolic ligament, and its incision should be sufficient for adequate examination of the peritoneum covering the pancreas. Dissection of the parietal peritoneum along the upper and lower edges of the pancreas allows for its abdominization, improves examination and palpation. If damage to the tail of the pancreas is suspected, it is necessary to mobilize it in a single block with the spleen and the left flexure of the colon. In this case, the tissues must be divided bluntly in the avascular zone between the anterior surface of the left kidney and the organs mentioned above. Inspection of the posterior surface of the body of the pancreas through the so-called inferior approach was proposed by one of the authors of the lecture [69] as a continuation of the technique of R. Cattell and J. Braasch [70]. A detailed presentation of operational techniques is not included in the scope of the lecture.

Unfortunately, even adequate mobilization of the pancreas does not always allow one to answer the question of whether there is a rupture of its duct or not. A certain depth of the tear and its relationship to the midline of the pancreas allows one to suspect damage to the RA [71]. Y. Hsu et al. proposed to perform lavage of the omental bursa and study amylase and lipase in this fluid. The authors showed a pronounced difference in the level of enzymes in the case of injury to the RA, its branches and in the absence of injury to the RV.

Proposals to perform intraoperative ERCP [73], fine-needle puncture of the gallbladder and cholangiography with pre-administration of morphine hydrochloride [74], despite the claim that such techniques reduced postoperative complications from 55 to 15% [75], have not stood the test of time and practice.

So, during the operation, the “subcapsular” hematoma should be opened and emptied and, if necessary, mobilizing the pancreas, inspect it. If the duct rupture is absent or doubtful, i.e., grade I-II damage has been verified according to OIS, the most gentle, precision hemostasis should be performed, and the omental bursa should be drained along its entire length with two tubes with a diameter of 24 Fr along the upper and lower edges of the pancreas. “Blind” suturing of pancreatic rupture and tamponade should be avoided - all researchers believe that this greatly increases the risk of traumatic pancreatic necrosis and its complications.

In case of a complete transverse rupture of the distal part of the RA, i.e., a grade III injury according to OIS, two surgical options are possible. Most authors are inclined to believe in performing distal resection of the pancreas [18, 25, 28, 76]. The spleen-preserving version of distal resection of the pancreas lengthens the operation by approximately 50 minutes [77] and is possible if the patient’s condition is stable [28, 78-80]. The long-term results of this operation in elective surgery are better than splenectomy [81, 82].

What to do with the pancreatic stump after distal resection? Many different methods of its treatment have been proposed: suturing a section of the pancreatic duct with a U-shaped suture with a non-absorbable monofilament thread or its external drainage, suturing the pancreatic stump with separate sutures with an absorbable thread [79, 83] or stitching devices [84], the use of biological adhesives and hemostatics, but the advantage one method or another has not been proven. Some authors do not consider it necessary to perform treatment of the pancreatic stump [85]. Drainage of the omental bursa at the end of the operation is mandatory [83].

The risk of diabetes mellitus after distal resection in elective surgery is estimated at 7.5% [86], 14-39% [87-89], and even 50.5% [90], and the likelihood of diabetes increases in chronic pancreatitis compared with benign or malignant tumor and when most of the pancreas is removed [91]. The risk of diabetes mellitus after distal pancreatic resection for trauma is 8.3-16% [1, 12].

An alternative to distal resection of the pancreas is the imposition of a distal pancreaticojejunostomy on a loop of the small intestine disconnected by Roux [83, 92]. This operation eliminates the possibility of diabetes mellitus, but has a specific complication - failure of pancreaticoenteroanastomosis.

As a case study, we present proposals for a complete transverse rupture of the pancreas to perform an end-to-side pancreatogastroanastomosis [9], to perform a central resection of the pancreas [93], and for a partial rupture of the pancreas while preserving its posterior wall, to apply a side-to-side pancreatojejunostomy [11, 94].

Damage to the pancreas of IV-V degrees according to OIS is the most difficult to choose a surgical method and its practical implementation. If the patient’s condition is stable and the surgeon has significant experience in hepatopancreatoduodenal surgery, pancreaticoduodenectomy in one of its variants (pylorus-sparing or gastropancreaticoduodenal) is recommended [95, 96].

The extremely serious condition of the victim is an indication for staged treatment (damage control technique) with temporary drainage and tamponade of the damaged area [25, 97-99]. The time before surgery and its volume should be minimized [100].

If the victim’s condition can be stabilized, the second stage of treatment is performed - pancreaticoduodenectomy. This tactic allows you to increase the chances of survival of victims in very serious condition; its disadvantage is a large number of postoperative complications [101].

If the surgeon does not have sufficient experience in operations in this area and does not plan the second stage of treatment, then only drainage of the omental bursa is indicated [5]. All the hard work of diagnosing and treating the specific complications that almost inevitably arise is transferred to the postoperative period.

Prescribing somatostatin or its analogs immediately after the diagnosis of PPC is advisable [102], and the earlier the drugs are prescribed, the better the treatment results [26]. For grade III and higher injuries, antibiotic prophylaxis and total parenteral nutrition are considered appropriate [5, 103], and the need for a jejunostomy for nutrition is discussed [104].

Organizational aspects of providing assistance, including the need to transfer some of the victims to a first-level trauma center, are excellently outlined in the article by S.F. Bagnenko and A.E. Chikin [105], and various algorithms for the diagnosis and treatment of PPC are presented in several works [4, 26, 30, 36, 106].

Thus, the obvious trend in injury surgery - balanced conservative treatment of victims, early operations only for strict indications, strict correspondence of the volume of surgery to the severity of injuries and the severity of the general condition of the victim, the introduction of minimally invasive procedures - is also relevant for the diagnosis and treatment of injuries to the pancreas. Conservative treatment of grade I-II pancreatic injuries is generally accepted [13], grade III is being introduced into practice [103], and grade IV-V is being promoted [107].

Minimally invasive treatment in the early stages after injury, if possible, improves the results of conservative therapy and reduces the incidence of specific complications [60, 108, 109, 110], which include traumatic pancreatitis [12, 20, 25, 26], parapancreatic cyst [1 , 56, 66, 11, 111], external pancreatic fistula [1, 112, 113], pancreatic duct stenosis [114], intra-abdominal abscess [30, 115]. Long-term results of endoscopic treatment are not always satisfactory [114].

According to various data [2, 14, 104, 116], predictors of an unfavorable outcome are the age of the victim, hemodynamic instability, closed injury and multiple injuries. Damage to the pancreas, even severe, is to a significantly lesser extent determined by the lethal outcome [30, 113, 117]. In hemodynamically stable patients with isolated pancreatic injury, only the time to correct diagnosis affects the outcome of treatment [118].

Combined injuries of the duodenum and pancreas, called complex in foreign literature, will be discussed in one of the following lectures.