Atrophic gastritis , or the more correct medical name atrophy of the gastric mucosa , is an irreversible process in which the death of cells in the gastric mucosa that produce gastric juice and hydrochloric acid occurs. Atrophy also includes the gradual replacement of stomach cells with connective tissue and cells similar in structure to the cells of the intestinal mucosa.

Atrophy of the gastric mucosa is a dangerous condition for health, since over time and especially in the presence of additional risk factors, it can lead to the development of stomach cancer.

Causes of atrophic gastritis

There are more than ten different causes, each of which can lead to atrophy of the gastric mucosa. Most often, this condition is the result of a long course of inflammation, against the background of chronic gastritis.

Chronic gastritis is a common disease (found in up to 30% of the population in various populations), which has a chronic and recurrent course, manifested by inflammation of the gastric mucosa and confirmed by morphological examination.

The causes of the development of chronic gastritis are:

- presence of Helicobacter pylori infection (H. pylory);

- inflammation caused by an autoimmune process, when your own immune system damages the cells of the gastric mucosa;

- long-term use of medications, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs);

- doudenogastric reflux, when the contents of the duodenum, including bile, are thrown into the stomach;

- prolonged contact with harmful substances during work;

- exposure to radiation;

- the presence of other chronic diseases, for example, celiac disease, Crohn's disease, sarcoidosis;

- food allergies;

- endocrine disorders;

- other infections (except H. pylori), fungi, parasites.

That is, in most cases, atrophy of the gastric mucosa is the result of the most common (80%) chronic gastritis caused by Helicobacter pylori infection, or autoimmune gastritis, which occurs in 1-2% of cases. This article discusses in detail the atrophy associated with these two causes.

O.Ya. Babak, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Director of the Institute of Therapy named after. L.T. Small Academy of Medical Sciences of Ukraine, Kharkov

Atrophic gastritis is understood as a progressive inflammatory process of the gastric mucosa, characterized by the loss of gastric glands. The clinical and morphological feature of atrophic gastritis is a decrease in the number of specialized glandulocytes that provide the secretory function of the stomach, and their replacement with simpler cells, including those that produce mucus. Extensive atrophy of the gastric mucosa is usually associated with hyposecretion of hydrochloric acid and impaired pepsinogen production.

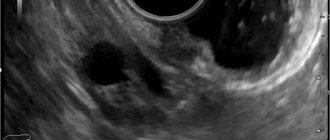

What is known today about atrophic gastritis? The most common etiological factors causing atrophic gastritis are Helicobacter Pylori (H. Pylori) infection and autoimmune gastritis. Moreover, the occurrence of the vast majority of atrophic gastritis is associated with H. pylori. The bacteria H. pylori, persisting on the gastric epithelium, cause chronic Helicobacter superficial gastritis. Long-existing superficial Helicobacter gastritis without appropriate treatment transforms into atrophic. Atrophic gastritis, as a rule, does not manifest itself clinically for a long time, therefore the diagnosis of chronic gastritis is rather morphological than clinical. The main method for diagnosing atrophic gastritis is endoscopic examination. During endoscopy, the esophagus, stomach, and duodenum are examined. With severe atrophy, the gastric mucosa has characteristic differences compared to that with, for example, superficial gastritis. The final diagnosis can be established by morphological analysis of biopsy samples of the gastric mucosa taken during endoscopy. Morphologically, atrophy is determined by a decrease in the number of functioning specialized cells of the stomach. It has been proven that in H. pylori-associated gastritis, atrophy processes more often occur when infected with certain strains (Cag A+ and Vac A+) of H. pylori. One of the morphological signs of atrophic gastritis is intestinal metaplasia, which has traditionally been considered as a precancerous change in the gastric mucosa. Other research methods - radiography of the stomach, ultrasound examination of the abdominal cavity and computed tomography - are not informative in terms of diagnosing atrophic gastritis.

What should you be wary of with atrophic gastritis? What is the prognosis of the disease? Hypothetically, the presence of atrophic gastritis in its natural course can have two scenarios. The first is that long-term chronic gastritis leads to a significant decrease in the acid-forming function of the stomach, requiring replacement therapy, without which signs of impaired digestive function will be observed. The second option is that as a result of long-term chronic persistent inflammation in the gastric mucosa, characteristic of H. pylori-associated gastritis, a disruption of cellular renewal in the stomach occurs, which contributes to the emergence of target cells for the influence of carcinogenic substances on them, and subsequently to cellular mutations. As a result, the normal cellular epithelium of the stomach is replaced by metaplastic, dysplastic and neoplastic. According to the WHO definition, dysplasia is understood as cellular changes in which part of the epithelium is replaced by cells with varying degrees of atypia. In the international classification of epithelial neoplasia of the digestive tract (2000), dysplasia is neoplasia, in other words, a tumor. So, atrophic gastritis can transform into stomach cancer. The greatest danger in terms of cancer development is atrophic gastritis with reduced acid-forming function of the stomach (cancer incidence is up to 13%). Among the currently known molecular mechanisms underlying hereditary predisposition to gastric cancer are: induction of TGF-β1 expression, partial polymorphism of the IL-1 gene cluster (IL-1β). As a result of the development of atrophy of the gastric mucosa, its antitumor protection is reduced, and conditions are created for the active influence of carcinogens. When severe atrophy of the gastric body epithelium occurs, the risk of developing gastric cancer increases 5 times compared to that with non-atrophic gastritis. The bacteria H. pylori are classified as biological carcinogens in relation to gastric cancer. Most researchers believe that H. pylori is the main etiological factor in the development of chronic gastritis, which is an obligatory link in the cascade of processes leading to stomach cancer. Based on an analysis of the results of multicenter studies, the International Agency for Research on Cancer under the WHO in 1994 recommended that H. pylori infection be considered an absolute carcinogen for humans. Currently, gastric cancer is considered as the end result of a long-term multi-stage and multifactorial process, in which cellular changes in the gastric mucosa are caused by disturbances in the microenvironment. This process is called the Correa cascade (1995) after the author who described it. It includes chronic gastritis, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and cancer. H. pylori-associated gastric carcinogenesis is a multi-stage process characterized by the development of chronic gastritis - the first step in the evolutionary cascade. Subsequent changes lead to the formation of atrophy, small intestinal (types I and II) and large intestinal (type III) metaplasia and dysplasia of the gastric epithelium, ultimately leading to gastric adenocarcinoma. It is atrophic gastritis that occupies a middle position in the chain of the above changes on the path to stomach cancer.

How to avoid the transformation of atrophic gastritis into stomach cancer? The answer to this question consists of parts of equal importance: the earliest possible detection of precancerous changes, their adequate treatment and prevention (prevention) of the manifestation of the latter. When observing patients with chronic gastritis, it is important to catch the moment when atrophy of the gastric mucosa occurs and begins to progress, and it is advisable to do this in a simple informative and non-invasive way.

Timely detection of atrophy of the gastric mucosa is the first diagnostic stage in identifying the risk of gastric cancer.

Numerous studies in recent years have shown that areas of complete and incomplete intestinal metaplasia of the gastric mucosa cannot be regarded as a reliable marker of an increased risk of developing gastric cancer. Research shows that it is much more important to assess not the type of metaplasia, but its volume. Thus, with a large volume of metaplasia exceeding 20% of the surface of the gastric epithelium, real conditions are created for the development of dysplasia with the subsequent formation of gastric adenocarcinoma. Consequently, the risk of developing gastric cancer increases with severe atrophy of the gastric epithelium, characterized by extensive foci of intestinal metaplasia. How can one determine the area of such a lesion in practice? It should be remembered that these changes occur at the cellular level and cannot be recognized with conventional endoscopy. An accessible and effective way to diagnose metaplastic changes in the gastric mucosa is the method of chromogastroscopy - intravital staining of the gastric mucosa with a dye (usually methylene blue), carried out during an endoscopic examination. This technique is based on the absorption of dye by foci of intestinal metaplasia, which makes it possible to assess their size, perform a targeted biopsy for histological analysis of the mucosal biopsy, and identify possible dysplasia or metaplasia. However, the morphological diagnosis of atrophic gastritis is associated with a number of difficulties. The difficulty of diagnosing atrophy using the morphological method is due to the fact that in the early stages the process is never diffuse, therefore, the results of gastrobiopsy can contribute to over- and under-diagnosis. With inflammation, the microscopic picture may change and the manifestations of atrophic gastritis may be inadequately assessed due to the false conclusion about the loss of glands. The subjectivity of the methodology is also high. All this makes us look for other reliable ways to test atrophic changes in the gastric mucosa. A number of minimally invasive hematological tests (Biohit test panel) have been developed to avoid diagnostic errors and provide a comprehensive assessment of the condition of the gastric mucosa, the degree of its atrophy and loss of normal glands and cells in the antrum and body of the stomach. During an endoscopic examination, detection for the presence of H. pylori must be carried out. In this case, urease or histological research methods (from gastrobiopsy specimens) should be considered the most appropriate. Determination of the level of serum pepsinogen (S-PGI) or the ratio of pepsinogen I to pepsinogen II (PGI/PGII) is a non-endoscopic method for diagnosing atrophic gastritis with damage to the body of the stomach. As the degree of atrophy of the gastric mucosa (loss of normal acid-producing glands) increases, the levels of S-PGI and PGI/PGII gradually decrease. Determination of the level of gastrin in blood serum, mainly gastrin-17 (SG-17), can be used as an indicator of the morphological state of the mucous membrane of the gastric antrum. That is, a decrease in SG-17 is a biochemical marker of atrophic gastritis with damage to the antrum of the stomach (loss of antral G-cells). Decreased levels of SG-17 and S-PGI can be considered a result of progressive atrophic gastritis with loss of normal glands and cells of the mucous membrane of the body and antrum of the stomach. G-17 is almost completely synthesized and secreted by G-cells of the antrum of the stomach. These cells are components of normal antral glands; in the case of progression of atrophic gastritis, their number decreases against the background of damage to the antral glands and the appearance of intestinal metaplasia. In H. pylori-associated gastritis, there is a tendency for serological levels of G-17 and PGI to increase. Low intragastric acidity contributes to an increase in the serological level of G-17, and vice versa. Permanent, long-term hypo- or achlorhydria leads to extremely high levels of G-17 in the blood. This is especially often observed with low acidity (atrophic gastritis with damage to the body of the stomach) in combination with preserved mucous membrane of the antrum. This clinical picture is most typical for autoimmune atrophic gastritis. If there are concomitant signs of mucosal atrophy in the antrum (multifocal atrophic gastritis), then SG-17 does not increase and the test panel shows low levels of S-PGI and SG-17. The overall accuracy of the test panel in diagnosing atrophic gastritis is about 80% (when compared with the results of endoscopy and biopsy). This test panel is a minimally invasive alternative for the initial evaluation of patients with suspected gastric atrophy and dysplasia. It allows you to reliably identify patients with various forms of gastritis, determine the localization and etiology of the pathological process, assess the likelihood of developing stomach cancer and build further tactics for managing the patient. Considering the connection between the occurrence of atrophy of the gastric epithelium and intestinal metaplasia with H. pylori infection, the choice of treatment and prevention of further progression of the process becomes obvious. The method of choice is anti-Helicobacter therapy. In 2002, Japanese researchers convincingly proved the possibility of regression of metaplastic changes in the gastric mucosa after successful destruction of H. pylori bacteria. Using chromoscopy, they were able to establish that within five years after successful anti-Helicobacter therapy, the size of the foci of intestinal metaplasia decreased by almost 2 times in comparison with the initial ones. Subsequent studies confirmed the feasibility of this therapeutic approach. Currently, there is no doubt about the need for anti-Helicobacter therapy for patients with atrophic gastritis. Preliminary data from several multicenter studies monitoring H. pylori -associated gastric precancer and cancer support reversal of gastric mucosal inflammation and associated atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, and genetic instability. In this regard, ideally, patients with H. pylori-positive chronic atrophic gastritis should undergo eradication therapy, and if there is no effect, a study to identify markers of genetic instability and careful monitoring. This recommendation is reflected in the international recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of diseases associated with H. pylori - Maastricht Consensus 3 (2005). To destroy H. pylori bacteria, as in the Maastricht Consensus 2 (2000), three- and four-component regimens of antibacterial drugs in combination with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in standard doses are recommended: PPI + clarithromycin + amoxicillin and PPI + tetracycline + metronidazole ( furazolidone) + colloidal bismuth. At the same time, it should be remembered that complete restoration of the structure of the mucous membrane in severe atrophy to normal requires a long time, and in some cases, apparently, this is not possible. In cases where pre-tumor processes do not undergo reverse development or progress, it is necessary to apply more radical methods of treatment, using the arsenal of modern endoscopic operations, up to resection of the gastric mucosa. The main goal of primary prevention of atrophic gastritis is timely and effective treatment of superficial Helicobacter gastritis. For this purpose, standard anti-Helicobacter therapy regimens are used, in accordance with the recommendations of the Maastricht Consensus 2 (2000) and 3 (2005). An important point is subsequent monitoring of the success of this therapy. Monitoring must be carried out using non-invasive methods (breath urease test or stool test). If eradication is unsuccessful, repeat courses of treatment. In addition, it has been proven that by adhering to a healthy diet, you can reduce the risk of cancer (progression of atrophy), which has been confirmed in studies conducted in a number of countries. It is recommended to avoid eating canned, pickled and smoked foods, stop smoking and drinking strong alcoholic drinks (especially in combination with fatty, fried, smoked and salty foods), and avoid overeating. It is necessary to control body weight, perform active physical activity, consume more fresh vegetables (including onions and garlic), fruits and natural juices, vitamins A, C, b-carotene, herbs, whole grains, and dairy products. In some developed countries of Europe and the USA, the introduction of a healthy lifestyle has led to a several-fold reduction in the incidence of stomach cancer; today this disease in these countries is considered rare, accounting for only 3% of malignant neoplasms. Monitoring - constant observation with periodic re-examination - is absolutely mandatory for patients with atrophic gastritis. So, at present, the need for special attention to atrophic gastritis is obvious. The integrated use of modern research methods - endoscopic, morphological, hematological (test panel) and others - contributes to its accurate diagnosis. The use of effective methods for the treatment and prevention of atrophic gastritis, the elimination of conditions that contribute to its development, present today a real opportunity to improve the prognosis of this disease and eliminate the risk of developing stomach cancer.

References 1. E.G. Burdina, E.M. Mayorova, E.V. Grigorieva, I.I. Timofeeva, O.N. Minushkin // Gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I in assessing the condition of the gastric mucosa // Russian Medical Journal, 2006, No. 2, p. 9-11. 2. H. Vaananen, M. Vauhkonen, T. Helske, I. Kaarijanen, M. Rasmussen, H. Tunturi-Hihnala, J. Koskenpato, M. Sotka, M. Turunen, R. Sandström, M. Ristikankare, A. Jussila, P. Sipponen // Non-endoscopic diagnosis of atrophic gastritis based on a blood test: correlation between the results of histological examination of the stomach and the levels of gastrin-17 and pepsinogen I in the serum // Clinical perspectives of gastroenterology, hepatology, 2003, No. 4, p. 26-32. 3. V.D. Pasechnikov, S.Z. Chukov, S.M. Kotelevets / Prevention of stomach cancer based on eradication therapy of pretumor diseases // Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology, 2003, No. 4, p. 11-19. 4. A.A. Sheptulin, V.A. Kyprianis / Diagnosis and treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection: main provisions of the Maastricht-3 conciliation meeting // Russian Journal of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, Coloproctology, 2006, No. 2, p. 88-91. 5. Kim N, Lim SH, Lee KH et al. Long-term effects of Helicobacter pylori eradication on intestinal metaplasia in patients with duodenal and behign gastric ulcers Dig. Dis. Sci. – 2000. – Vol. 45. – 1754-1762. 6. Malfertheiner P., Megraud F., O'Morain C. et al. Current concepts in the management of Helicobacter pylori infection – The Maastricht 2 Consensus Report // Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. – 2002. – Vol. 16. – P. 167-180.

What happens to mucosal cells during atrophy?

The gastric mucosa consists of three layers. The top layer covering the entire inner surface of the stomach is formed from cells that produce mucus to protect against the aggressive effects of gastric juice. Beneath it is the most important layer, called the “lamina propria of the stomach.” It contains the glands of the stomach, which produce substances that form gastric juice - hydrochloric acid, pepsin, hormones (internal Castle factor). The third layer contains muscle cells, the main task of which is to ensure the mobility of the gastric mucosa to move food along.

Atrophy of the gastric mucosa affects the upper layer and the lamina propria of the stomach and is an almost irreversible process that can be slowed down if the causes of inflammation are eliminated.

The gastric mucosa is exposed to an aggressive environment, so its cells are completely renewed every three days. The inflammatory process, which develops as a result of the influence of external factors, for example, a bacterial infection or internal causes, for example, the reaction of the immune system, disrupts the process of renewal (regeneration) of cells of the gastric mucosa, including the cells of the gastric glands that produce gastric juice. As a result, the cells of the stomach glands die and are replaced by connective tissue cells, as well as cells similar in structure to intestinal cells.

This process can be diagnosed using histological examination of samples of the gastric mucosa. If only a decrease in the number of cells of the gastric glands is detected, then they speak only of atrophy of the gastric mucosa. If intestinal cells are found in the test sample, then a diagnosis of atrophy with intestinal metaplasia is established. Metaplasia is the appearance of cells that are atypical for a given organ.

Folk remedies and diet

Diet is a prerequisite for stomach treatment

Diet is an integral part of treatment. Since the gastric mucosa is affected, all food should be light, prepared without the use of oil, in order to reduce the load on the sore stomach. Coarse fibers should be excluded. It is advisable that the food be finely chopped or twisted. It is necessary to monitor the temperature of food. You will have to give up everything hot and cold. Dishes should only be warm.

All products containing spices, seasonings, carcinogens, large amounts of salt, smoked foods, carbonated and alcoholic drinks, canned food, cream cakes, chocolate, homemade and store-bought pickles are prohibited. Fried foods and fatty meats should also be excluded from the diet. Meat dishes should be lean and steamed. Boiled vegetables are better. Low-fat and non-acidic dairy products are allowed. You can use pureed soups made from vegetables, without meat broths or frying. Drinks allowed are non-acidic natural mousses and jelly, still mineral water, and weak tea. \

Remember that medicinal mineral water, which is sold in pharmacies, cannot be drunk unlimitedly. This is a medicine containing a certain amount of substances and minerals. The dosage is determined by the doctor.

Try in every possible way to increase your appetite to prevent exhaustion. Let the dishes be served beautifully; they should look attractive to you even without spices and mayonnaise. As an additional treatment, your doctor may prescribe herbal teas or tinctures of herbs that improve digestion. So, for atrophic gastritis, a mixture of calamus rhizome, honey and cognac, as well as St. John's wort, plantain, yarrow, peppermint, cumin, flax seed, sage, dill is useful. Natural blueberries, ground with sugar, will help restore the gastric mucosa. You need to take a teaspoon on an empty stomach in the morning. But the berries must be fresh. Jam will not give the desired effect, since most vitamins are destroyed during heat treatment.

How to correctly diagnose gastric mucosal atrophy?

To diagnose atrophic gastritis, FGDS (gastroscopy) with the collection of at least 5 biopsies (small fragments of mucous membrane) from different parts of the stomach. The number of biopsy samples is determined by the structure of the stomach, since atrophy in different sections develops at different rates, and therefore it is necessary to take samples from all five sections.

The diagnosis is established by a morphologist after a histological examination. Based on this study, treatment is selected and the frequency of examinations is determined for the timely detection of the oncological process.

Also, to assess the severity of atrophy, determination of the activity of the secretory function of the stomach using a laboratory blood test is used - Gastropanel (link).

Diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori infection is carried out using biopsy specimens and a 13C-urease breath test .

For autoimmune gastritis, laboratory diagnostics are carried out using a blood test to determine antibodies to stomach cells and internal Castle factor.

A few words about serum markers

We have a diagnostic algorithm for identifying stomach diseases, which is recommended for all patients who have pain or discomfort in the upper abdomen.

Pepsinogens

There are seven isoforms of pepsin precursors, five of which are designated as group Pepsinogen I of the main cells of the stomach body and Pepsinogen II, uniformly secreted by the glands of the entire stomach and duodenum. Pepsinogens formed in the stomach are absorbed into the blood and determination of their serum level is a generally accepted marker of atrophic gastritis “serological biopsy”.

A decrease in the level of Pepsinogen I indicates the severity of atrophic gastritis of the body of the stomach, and since the activation of Pepsinogen I into active pepsin occurs with the participation of hydrochloric acid, then the level of Pepsinogen I can roughly represent the level of stomach acidity. Pepsinogen II is produced in all parts of the stomach and in the duodenum. As the severity of atrophy increases, the ratio of serum levels of Pepsinogen I and Pepsinogen II decreases, which indicates the severity of atrophy and the spread of the process.

Gastrin

Gastrin-17, produced in the outlet section of the stomach after stimulation of cells by various factors (stomach distension, protein foods). In case of atrophy of the gastric antral mucosa, the secretion of Gastrin-17 decreases. To assess the presence and severity of the atrophic process in the stomach, it is necessary to conduct a protein stimulation test, the decrease of which shows the severity of atrophy; in the case of atrophy of the mucous membrane of the antrum of the stomach, the secretion of Gastrin-17 is proportionally reduced. In patients with severe atrophic gastritis in the antrum of the stomach, the risk of developing stomach cancer is 90 times higher than in people with normal gastric mucosa.

Homocysteine

Homocysteine is an early marker of cellular functional deficiency of B12, B6, folic acid due to the development of atrophic gastritis and other reasons - age, smoking, Helicobacter pylori infection, etc. With atrophic gastritis, the level of homocysteine increases in the blood and becomes toxic to the body. When donating blood for homocysteine, you should avoid protein foods, vitamins, and hormonal contraceptives 1 day before the test. This test can be an addition to the Gastropanel or an independent test for other diseases.

Atrophic gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection

After infection with the bacterium Helicobacter Pylory, inflammation and chronic non-atrophic gastritis develop in the gastric mucosa. At the beginning of the disease, the glands of the stomach produce a sufficient amount of gastric juice. If left untreated, inflammation becomes more active and spreads to all parts of the stomach, leading to mucosal atrophy) and partial replacement of stomach cells with intestinal cells (intestinal metaplasia).

Symptoms

At the onset of the disease, gastritis is asymptomatic. As atrophy progresses, symptoms appear associated with a decrease in the production of hydrochloric acid and other components of gastric juice:

- loss of appetite,

- belching of air or rotten belching;

- nausea;

- feeling of heaviness and fullness in the stomach;

- bad breath; salivation, unpleasant taste in the mouth;

- rumbling, bloating;

- intolerance to certain foods;

- unstable stool;

- dull, aching pain that intensifies after eating;

- weight loss.

Treatment

Eradication (destruction) of Helicobacter Pylory is the first stage of treatment for this variant of atrophic gastritis.

Diagnostics

A gastroenterologist and endoscopist are involved in the diagnosis and treatment of gastritis with low acidity. The specialist examines the patient and conducts a number of examinations:

- morphological studies;

- X-ray of the stomach;

- esophagogastroduodenoscopy;

- endoscopic biopsy;

- gastroscopy;

- determination of pepsinogen level;

- gastric probing with intragastric pH-metry;

- examination of gastric juice;

- diagnosing pylori using stool ELISA, PCR testing, detection of antibodies in the blood and a breath test for this microorganism.

The purpose of these studies is not to confuse the disease with other pathologies and to make an accurate diagnosis. Based on the examination results, the gastroenterologist prescribes a treatment regimen. If required, the attending physician will refer you for a consultation with a nutritionist, who will create an appropriate diet. In some cases, to eliminate concomitant diseases, consultation with other specialists of a narrow focus (cardiologist, therapist) is required.

Autoimmune atrophic gastritis

With this type of chronic gastritis, stomach cells are damaged by antibodies produced by the body's own immune system. In this case, chronic inflammation develops, leading to atrophy of the gastric glands and a decrease in the production of hydrochloric acid and internal Castle factor, which ensures the absorption of vitamin B12. A significant decrease in the production of intrinsic factor of Castle can cause anemia B12-deficiency anemia (pernicious anemia) - a disease characterized by impaired hematopoiesis.

Symptoms

The symptoms of autoimmune atrophic gastritis are similar to the symptoms of atrophy caused by Helicobacter pylori infection.

Additionally, anemia develops; autoimmune gastritis can often be accompanied by other autoimmune diseases.

Treatment

There is no specific treatment for autoimmune gastritis; treatment with corticosteroids is used only in exceptional cases.

Types of disease

Depending on the location and accompanying symptoms, gastritis can be of the following types:

- Atrophic gastritis with low acidity. Thinning of the mucous membrane is observed, tissues die and lose their protective function. It is divided into antral and diffuse. A severe decrease in the level of acid in the stomach is the most dangerous condition, as it can provoke cancer. The exact cause of its development has not yet been established, but overeating, poor diet, and taking hormonal medications and antibiotics as self-medication play an important role.

- Chronic gastritis of the stomach with low acidity. This disease, in turn, is divided into the stage of compensation, partial compensation and decompensation. The chronic variant develops slowly: initially, acidity increases significantly. If treatment is not started, the acid-producing cells die and little is produced. Acidity returns to normal. With further progression, atrophy (death) of the gastric mucosa begins, and a chronic version of the disease occurs. Chronic gastritis with decreased secretion is often caused by the bacterium H. Pylori.

Symptoms

A distinctive feature of atrophic gastritis is the likelihood of developing an inflammatory process without pain. The patient may experience discomfort in the digestive system under the influence of certain factors. With pathology, deviations in the digestion of food and bowel movements are sure to occur.

In most cases, there are no acute pains with this disease. Severe pain syndrome appears only in the presence of concomitant complications.

General symptoms:

- aching pain in the area of the digestive organs after eating;

- pallor, dry skin;

- lack of appetite, weight loss;

- increased bleeding

- excessive sweating;

- Iron-deficiency anemia;

- rumbling in the stomach after eating;

- alternating constipation with diarrhea;

- belching air with an unpleasant odor;

- feeling of fullness in the intestines;

- excessive fatigue of the body;

- general weakness of the body.

Prevention

Atrophic gastritis is a chronic disease of the digestive tract. Its primary prevention is a healthy diet and personal hygiene. Secondary measures to prevent the disease include regular examination by a gastroenterologist. The disease can develop in an asymptomatic form. Only a doctor can detect the progression of the disease.

Prevention measures:

- replenishment of vitamins in the body;

- strengthening the immune system;

- rejection of bad habits;

- taking medications according to instructions;

- exclusion of a sedentary lifestyle;

- timely treatment of diseases of the digestive system;

- adherence to healthy eating rules;

- excluding neglect of personal hygiene rules.