Heterotopia of the gastric mucosa theory of origin

The presence of heterotopic gastric mucosa as aberrant gastric epithelium in the proximal esophagus was first described in 1805 by Schmidt at autopsy. Other zones of heterotopia of the gastric mucosa have been reported, with their location in the duodenum, small intestine, cystic duct, gall bladder, rectum and anus. Heterotopy of the gastric mucosa in the esophagus in foreign literature is often referred to figuratively as an “inlet patch” and is most often found in the cricoid region (postcricoid part) of the esophagus at the level of or just below the upper esophageal sphincter. Ectopic mucosa may also be found in other parts, including the distal esophagus. There are three theories of the origin of heterotopia, including congenital origin, metaplastic transformation and rupture of esophageal gland cysts. In the literature, the origin of heterotopia foci is generally accepted as a congenital anomaly. From the development of the esophagus in the 24th week of pregnancy, the squamous lining replaces the cylindrical lining starting from the middle of the esophagus in both directions, and this explains the location of gastric-type mucosal lesions in close proximity to the esophageal orifice. It is assumed that the endodermal cells of the primary intestine have the ability throughout the gastrointestinal tract to differentiate and undergo hyperplasia or physical movement of the gastric epithelium in a manner unknown to science. Another theory is the acquired theory, which depends on the chronic acid injury seen in Barrett's esophagus. This problem is responsible for the transformation of the squamous lining of the esophagus into a columnar cell lining. Another less common theory suggests rupture of retention cysts of the proximal esophagus glands.

Mobility of the proximal edge of the gastric folds associated with respiration

Many Japanese endoscopists believe that the US definition of the gastroesophageal junction EGJ is inaccurate because the proximal edge of the gastric folds is not in a constant position and can move significantly up and down depending on the volume of air in the esophagus. In addition, during deep inspiration, the proximal edge of the folds shifts and moves downward. Therefore, except for a few authors, most Japanese endoscopists believe that the distal edge of the palisade vessels is a more appropriate definition of the gastroesophageal junction of the EGJ than the proximal edge of the gastric folds.

Prevalence of heterotopia of the gastric mucosa

The reported prevalence of gastric mucosal heterotopia in the cervical esophagus ranges from 0.1 to 14.5%, but has been reported to be up to 70% at autopsy. The discrepancy between retrospective and prospective studies is a clear indication that retrospective data include endoscopy, in which heterotopic lesions were often ignored or missed. The relatively high prevalence of heterotopic lesions in some studies compared with others may be explained by the special interest of some endoscopists in deliberately looking for these changes. Although the condition is mostly asymptomatic and discovered incidentally during the evaluation of other gastrointestinal complaints, in rare cases patients describe pain and dysphagia. A sensation of a lump in the throat, hoarseness, odynophagia, dysphagia, or oropharyngeal burn (with regurgitation) may be symptoms that occur in 6.2-20% of cases. These symptoms usually refer to the release of acid, which is produced by the heterotopic focus of the gastric mucosa. It was possible to observe in almost 0.5 million cases that dysphagia or odynphagia, regurgitation and a lump in the throat were significantly more common in patients with foci of heterotopia in the cervical esophagus. Most symptoms were reported to be mild.

Is the lower segment of the esophagus actually lined with columnar epithelium?

The distance between the gastroesophageal junction of the EGJ and the dentate line of the SCJ on gross examination at autopsy has been described in two articles. Bombeck et al. In 21 autopsies, this distance was reported to range from 5 to 21 (mean 11) mm, whereas we reported a range from 0 (14 cases) to 10 (mean 3) mm in 50 Japanese cases. In the latter study, the gastroesophageal junction EGJ was defined as the line between the angles of the opening of the esophagus and the greater curvature of the stomach. The definition of gastroesophageal junction EGJ used by Bombeck et al. (the point of the esophagus that expands into the stomach) was essentially similar to ours. The results showed that the incidence of short-segment CLE is higher in Western countries than in Japan. In Japan, the gastroesophageal junction of the EGJ is considered to coincide with the SCJ as the distance between them is often 0 mm based on our study of autopsy cases. Thus, the gastroesophageal junction of the EGJ can be defined as the dentate line of the SCJ. Shimoda et al. also reports that the normal gastroesophageal junction of the EGJ closely follows the straight (not zigzag) jagged line of the SCJ, and this alignment of the EGJ with the SCJ is observed in most Japanese people. When endoscopically defined as the gastroesophageal junction EGJ at the distal edge of the palisade vessels, or macroscopically defined as the line connecting the esophageal opening angle and the greater curvature of the stomach, the distal segment of the esophagus 2-3 cm of the esophagus is usually lined with squamous epithelium in Japanese patients.

©

print version

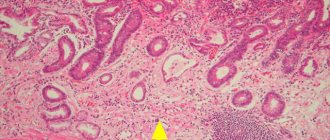

Diagnosis of heterotopia of the gastric mucosa

It is difficult to detect heterotopic gastric mucosa during routine endoscopy. The endoscopist should be aware of this lesion, located in the area of the upper esophageal sphincter. There was no correlation of lesion detection with the use of sedation. On endoscopy, the lesion appears as a spot most often on the lateral or posterior walls a few centimeters distal to the upper esophageal sphincter, salmon-colored, round or oval in shape with a flat, slightly raised or depressed surface and may have raised edges. The lesion will be more likely to be detected when the endoscope is slowly withdrawn through the upper esophageal sphincter region. Contractions of the upper esophageal sphincter during endoscopy make inspection and biopsy of this area difficult. The lesions are recognized at a distance of 16 to 21 cm from the incisors. The final diagnosis of heterotopia of the gastric mucosa is confirmed by biopsy. In the biopsies studied, the most common histological type was the acid-producing or cardiac type of gastric mucosa, followed by antral and mixed type gastric mucosa. Biopsies from small heterotopic lesions were more likely to contain cardiac-type mucosa, whereas biopsies from larger lesions were more likely to consist of corpus mucosa. At the border between the columnar epithelium and the squamous lining of the esophagus, the predominant type of columnar epithelium was cardiac. In the immediate vicinity of the heterotopia border, yellow spots are often observed within the squamous epithelium. They contain foci of columnar epithelium located beneath the squamous epithelium of the esophagus, defined by some pathologists as the esophageal glands proper. It is noteworthy that these yellow spots are similar to the epithelium adjacent to the dentate line of the esophagogastric junction. It is known that the submucosal glands of the esophagus are grouped at both ends of the esophagus. A compelling, although unproven, concept is that such lesions represent a precursor to columnar metaplasia of the esophagus. According to this concept, intraepithelial cysts rupture and are exposed to the surface to construct columnar metaplasia.

Interesting statistics

Takeji et al. reported that ectopic gastric mucosa in the esophagus is more common in men than in women. There is a non-significant trend towards a higher prevalence of heterotopic lesions between the ages of 50 and 70 years compared with younger and older adults. According to the literature, one focus is most often detected, but there may be several lesions in close proximity to others.

The clinical significance of heterotopic lesions is mainly associated with acid complications and neoplasms. Inflammatory and pathological changes such as atrophy, intestinal metaplasia, dysplasia and carcinoma, even angiodysplasia have been found in these lesions. Stricture, erosion, ulceration, bleeding, cystic dilatation of glands, fibrosis, intestinal metaplasia, membrane, perforation, tracheoesophageal fistula and polyps have been described in the literature as complications of heterotopic gastric mucosa. Intestinal metaplasia has been reported associated with the occurrence of adenocarcinoma in a heterotopic lesion of the gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus. Alagozlu et al. estimated the frequency of malignancy of heterotopic foci of the gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus from 0 to 1.56%. More than fifty cases of adenocarcinoma resulting from heterotopia of the gastric mucosa in the cervical esophagus were reported between 1950 and 2016. However, there are no long-term data on the risk of neoplasia arising from intestinal metaplasia at a site of heterotopia.

Relationship with other diseases

The relationship between glycogenic acanthosis and heterotopia has not yet been determined. Glycogenous acanthosis is small, discrete elevations in the lining of the esophagus. Glycogenic acanthosis is known to be a common disease, with an incidence of 3.5%, and may be associated with reflux esophagitis.

The ectopic gastric mucosa is an ideal site for Helicobacter colonization with a positive detection rate of up to 86% if HP is present in the stomach. Although the role of HP in heterotopic lesions remains unclear, it has been determined that Helicobacter can cause histological changes similar to those in the gastric mucosa.

Function

Complete digestion of food does not occur in the stomach. The gastrointestinal tract has many related, no less significant functions. Only proteins inside it completely disintegrate. The process is accompanied by the work of gastric juice containing hydrochloric acid and pepsin. The remaining food ingredients only change consistency and are crushed.

The main functional feature of the gastric region is characterized by the following types:

- storage - the organ stores chewed, swallowed food. The delay period, the initial stage of digestion, takes 1-2 hours. Then, through the lower third of the stomach, it is gradually pushed into the duodenum. If the organ is full, then progress is delayed, and only part of the section is gradually released;

- secretory function - a piece of food is processed using gastric juice;

- absorption - preliminary stage;

- metabolism;

- protection from pathogenic microorganisms and poor quality food products;

- production of hormones using the endocrine system.

Relationship between heterotopic gastric mucosa and Barrett's esophagus

The relationship between heterotopic gastric mucosa and Barrett's esophagus remains controversial. There are also reports that heterotopia is associated with an increased risk of Barrett's esophagus. Barrett's esophagus is an acquired precancerous lesion, and the cell origin likely involves multipotent stem cells. According to some reports, almost half of all patients with heterotopic lesions also have Barrett's esophagus. Although the prevalence of focal heterotopia was higher in patients with predominant symptoms of reflux, hiatal hernia, reflux esophagitis, or Barrett's esophagus than in patients without these conditions, these relationships were not statistically significant. Only the higher prevalence of heterotopic lesions was significant in patients with a columnar esophagus (CLE) of at least 0.5 cm in length and any columnar epithelium on histology (p = 0.02, odds ratio 2.1). There was no significant correlation between the degree of reflux esophagitis and the presence of heterotopic lesions, neither between the length of the CLE and the presence of heterotopia, nor between the length of the CLE and the maximum diameter of the heterotopic lesions.

There are conflicting definitions among different guidelines regarding histopathological verification of Barrett's esophagus. Some guidelines consider the presence of intestinal metaplasia as mandatory, whereas others require only columnar cell epithelium. Cardiac-type mucosa in the lower esophagus has been shown to be an acquired type of mucosa and is likely a precursor to intestinal metaplasia and adenocarcinoma. Therefore, consideration should be given to cases with endoscopically detected lining of columnar cell epithelium in the lower esophagus (CLE), in which histological evaluation revealed only cardiac-type mucosa and no intestinal metaplasia. Only for this category of CLE there was a significant association with heterotopic lesions.

Introduction

International meetings and medical journals make it easy for physicians to exchange opinions. However, definitions, concepts and opinions in the field of gastroenterology vary widely between countries. With regard to the esophagus and stomach in particular, there are clear differences in the endoscopic definition of the gastroesophageal junction (EGJ), the primary or secondary origin of Barrett's adenocarcinoma (BA), the definition of Barrett's esophagus (BE), and histological criteria for high-grade dysplasia (HGD). or well-differentiated adenocarcinoma with early invasion of the esophagus and stomach. Here we discuss these differences in terms of their practical application.