Moshe Shine

The history of abdominal drainage is as old as surgery itself (1). However, abdominal drainage is still a subject of debate and constant discussion. Even 100 years ago there were passionate proponents of drainage, like Robert Lawson Tait (1845-1899), who said: “When in doubt, drain!” There were also skeptics, like JL Yates (1905), who said: “Drainage in general peritonitis is physically and physiologically impossible”! There were also those like Joseph Price (1853-1911): “There are people who ardently defend drainage, and there are those who categorically deny it. Both are right in their own way.”

100 years have passed, during which operative surgery and supportive care have progressed continuously. But what about drainage? Are there fewer discussions and contradictions today? What awaits drainage tomorrow?

In this short post I try to answer these questions from the perspective of drainage for abdominal and abdominal infections. Elective surgeries will be mentioned only as part of the discussion. Percutaneous drainage, both primary and postoperative, is outside of our discussion.

Drainage classification

Drains are installed for therapeutic or preventive reasons.

Medicinal:

- To ensure the outflow of intra-abdominal fluid or pus (periapendicular abscess, diffuse peritonitis).

- To control the source of infection if it is impossible to remove it by other, radical methods; for example, with an external intestinal fistula (duodenal stump).

- Preventive:

- To prevent recurrence of infection - to evacuate residual serous fluid or blood, prevent the formation of an abscess.

- To monitor expected or probable leakage from the suture line (colic anastomosis, duodenal stump, cystic duct).

- To report complications (in the hope that drainage will work in case of bleeding or leakage of chyme from the anastomosis).

It is better, rather than discussing a rigid classification, to look at the problem of drainage through the eyes of a general surgeon. What are the common tactics? What is the practice for general surgery?

The literature is a poor source of information about how common abdominal drainage is in emergency surgery. Analyzing several publications from individual clinics or collective reviews on drainage for specific conditions, we cannot draw a conclusion about the dominant trends. Therefore, we present the opinions of general surgeons - members of SURGINET - and the results of an international Internet discussion (2) regarding their views on abdominal drainage. Of the 700 members, only 70 responded. Although this is quite small, it correlates with the frequency of Internet responses received for any online survey.

The survey involved 71 respondents, all general surgeons, many of them not academic specialists, but earning their bread and butter through practical work, from a total of 23 countries. Most of all (14) are from the USA, and in total from North America - 18, Western Europe - 10, Eastern Europe - 7, Asia - 15, including Israel and Turkey; Latin America – 15, Australia and South Africa – 3 each.

Surgeons who are active in the Internet survey are, as a rule, more interested, active, and familiar with the literature and modern practice in other activities. The survey results reflect inconsistencies and geographic differences in their surgical practices.

Common situations where drainage may be used

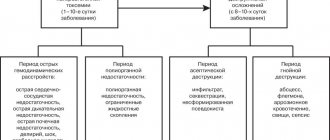

Acute appendicitis

In table Figures 1 and 2 summarize the surgeons' responses. “Simple” or “phlegmonous” appendicitis was excluded. Only complicated forms are discussed: when the appendix is black, there is usually some fluid in the pelvis, but it is not obvious pus. As follows from the table. 1, only one respondent drains the cavity in this situation. Next, when the appendix is perforated, a laparotomic or laparoscopic surgeon removes the appendix and sucks out the pus present around the appendix. In these cases, the surgeon can destroy the barrier of the omentum or loops of the small intestine, exposing a small abscess of a few cubic millimeters, and the pus is also aspirated. Table 2 shows that 80% of respondents do not install drainage in this situation. However, there is no geographical pattern. Table Figure 3 illustrates advanced cases where perforated appendicitis is combined with a “pus everywhere” situation - in the pelvis, along the right lateral canal, even in the upper floor. And, although 80% of surgeons do not install drainage in this situation, there is a geographic dependence: they never or almost never drain the abdominal cavity in North and Latin America, and quite often in the Asian world. This depends on how the surgeon views the role of drainage in the treatment of diffuse peritonitis; complications will be discussed later.

Table 1. Do you place drainage after appendectomy for gangrenous appendicitis?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 18 | |

| Western Europe | 10 | 10 | |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 7 | |

| Latin America | 15 | 15 | |

| Asia | 15 | 14 | 1 |

| Australia | 3 | 3 | |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 71 | 70 (98%) | 1 |

Table 2. Do you place drainage for perforated appendicitis, when there is little pus and it is present locally?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 14 | 4 |

| Western Europe | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Latin America | 15 | 11 | 4 |

| Asia | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Australia | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| South Africa | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Total | 71 | 56 (78%) | 15 |

Table 3. Do you place drainage for perforated appendicitis with diffuse spread of pus?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 18 | — |

| Western Europe | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 5 | 2 |

| Latin America | 15 | 14 | 1 |

| Asia | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| Australia | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| South Africa | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 71 | 55 (77%) | 16 |

Rules for recovery after appendicitis removal

23.06.2021

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendage of the cecum, commonly called the appendix. The disease appears unexpectedly and develops quite quickly.

There are several symptoms of appendix exacerbation:

- dull, gradually increasing pain in the area of the right side in the lower abdomen ;

- vomiting and nausea ;

- rapid rise in temperature;

- lethargy and weakness.

Often appendicitis requires surgery to remove . But do not forget that after the operation there is a mandatory recovery period. Rehabilitation will improve healing and recovery of the body. After the operation there is a recovery period in the hospital . This period lasts up to two weeks. Medical staff monitors body temperature and blood pressure. Processes and ties the postoperative suture. Controls the occurrence of complications and prevents their spread. After surgery , you must not eat for a day. Only after about six hours can you drink some liquid. On the second day, you can add broth to the diet, most importantly with a small amount of fat. After about ten days, the sutures are removed, and the internal sutures dissolve on their own.

The first rule of successful recovery is diet .

In the first period after surgery , only broth and liquid porridge are consumed.

In the subsequent period, you can start consuming the following products:

- yoghurts, kefir and cottage cheese with a minimum amount of fat;

- dietary meat broths;

- meat and fish, grated, boiled;

- boiled vegetables in the form of puree;

- water.

Use excluded:

- foods high in salt;

- mayonnaise, ketchup and similar sauces;

- bakery products, sweets;

- sausage products;

- legume products;

- alcohol and carbonated drinks.

The second rule is maintaining proper physical activity.

During the first days after surgery , you must be careful when moving. Try to perform movements smoothly and carefully. In the future, a course of exercise therapy for better recovery. Eight weeks after discharge from the hospital , you are only allowed to walk at a leisurely pace and perform a course of exercise therapy . You cannot perform full-fledged physical exercises, walk or run quickly.

The final rule is a series of simple everyday conditions.

Swimming and bathing should be avoided. It is better, instead, to wipe yourself with a damp towel. After all, there is a high chance of catching an infection from the water and developing complications. You should forget about visiting baths and saunas for at least a month. Tanning will also not be beneficial; you should avoid exposing the scar to direct sunlight. Smoking along with alcohol is excluded for at least a couple of months.

Sexual activity should be limited and try not to strain the stomach so as not to cause the seam to diverge. It is worth wearing bondage to strengthen the abdomen , especially for overweight people. By following the above instructions and rules, the body will quickly return to normal.

Published in Surgery Premium Clinic

Drainage for acute appendicitis

In 1979, O'Connor and Hugh, in an excellent review, concluded: “Intraperitoneal drainage is of little value in phlegmonous, gangrenous, or perforated appendicitis. However, drainage is indicated if there is a limited purulent cavity or a gangrenous stump that is imperfectly closed” (1).

I will not overwhelm you with details of all the available literature, since Petrowsky et al. recently released an excellent analysis of these studies (3). After presenting individual studies, including their own meta-analysis, the authors concluded that “drainage does not reduce the incidence of postoperative complications, and even appears to be harmful in terms of the formation of intestinal fistulas (the latter was observed only in drained patients). Drainage should be avoided in any form of appendicitis” (4).

Drainage after appendectomy for phlegmonous and gangrenous appendicitis is not needed. Most surgeons who took part in the survey understand this. What is said about perforated appendicitis with local formation of a purulent focus? Of our respondents, 22% will install drainage. As will be shown below, a “formed” or “unopened” abscess, according to most surgeons, is a good indication for installing drainage. But an abscess against the background of perforated appendicitis is not “unopened”: after the surgeon destroys its wall and evacuates the pus, the potential abscess space is filled with nearby loops of intestine, mesentery and omentum. Thus, the source of infection is removed, the abdominal cavity is cleaned by toileting. The peritoneal defense mechanism is then activated, supported by a short course of antibiotics, with complete eradication of bacteria without the presence of an irritating foreign body (4).

Uncertain closure of the appendiceal stump as a justification for drainage seems anachronistic. Safe closure is possible even in rare cases where perforation occurs at the base of the appendix, by placing a suture or stapler on the dome of the cecum.

Of our respondents, 23% use drainage for appendicitis complicated by diffuse peritonitis. However, as will become clear later, these are the same surgeons who advocate drainage for generalized intra-abdominal infection. And drainage in this situation - after controlling the source of infection - seems useless.

Description !

Appendicitis is an inflammation of the appendix, a vermiform appendage of the cecum located in the lower right part of the abdominal cavity. The appendix does not have any specific function. Appendicitis manifests itself as pain in the right lower abdomen. However, for most people, the pain begins around the belly button and then moves to the right and down. As inflammation increases, the pain from appendicitis usually gets worse and becomes more intense over time. Although anyone can develop appendicitis, it is most common in people between the ages of 10 and 30. Typically, an inflamed appendix is removed surgically.

Acute cholecystitis

Nowadays, the surgeon often performs “difficult” laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LCE) in patients with advanced acute cholecystitis. The preparation is not easy, the time is considerable, and the discharge from the liver causes outrage. To complete the procedure, a transition to laparotomy is possible. The question remains: is it reasonable to leave drainage in the area of the gallbladder bed or under the liver? A third of respondents will answer “YES” (Table 4). Please note that the emphasis in the question was on the expression “routine drainage”. Many respondents leave it selectively, in case of unfavorable closure of the cystic stump or in anticipation of active exudation.

Table 4. Do you place drainage after open cholecystectomy (OCE) or LCE for severe acute cholecystitis?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 12 | 6 |

| Western Europe | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 1 | 6 |

| Latin America | 15 | 14 | 1 |

| Asia | 15 | 7 | 8 |

| Australia | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 71 | 47 (66%) | 24 |

Drainage after cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis

A large prospective randomized study in 1991 and a meta-analysis of 1920 patients (ACA) summarized 10 similar studies. It was shown that when comparing patients with and without drainage in terms of mortality, reoperation or drainage due to bile accumulation, there were no differences. Wound infection more often accompanied patients with drainage (5). Thus, on the eve of the end of the era of BCI, routine drainage - the sacred cow of biliary surgery - was abandoned in many centers.

What is the trend in emergency LCE? In a recent study of Australian surgeons, drainage was left routinely in 1/3 of cases (6). Another small randomized trial comparing patients with and without drainage for LCE examined the effect of drainage on postoperative pain and nausea, in terms of gas removal, and found no difference (7). If routine drainage is pointless in ACE, why is it indicated in LCE? Therefore, Petrowsky et al. (3) drainage is not recommended for both ACE and LCE. In a prospective study of 100 patients who underwent LCE for acute cholecystitis, all of them underwent cholescintigraphy one day after surgery. Bile leakage was detected in 8, but all of them were asymptomatic (8). Most postoperative collections, be it bile, serous fluid or blood, remain asymptomatic, the fluid is absorbed by the peritoneum and this is well known from ultrasound studies since the time of AChE.

Drainage is much more effective at removing bile than stool or pus. Therefore, it is logical to leave a drain if the surgeon is concerned about possible bile leakage. For example, if a subtotal cholecystectomy is necessary, or when there are difficulties with sealing the cystic duct, or there is a suspicion of additional bile ducts in the area of the gallbladder bed, which manifests itself in the form of bile leakage from the surface of the bed.

Thus, although most patients do not require drainage, if the surgeon is concerned about possible bile leakage or excessive serous fluid, drainage is appropriate. In most cases, almost nothing is separated through such drainage. It is extremely rare that preventive drainage becomes therapeutic in the case of profuse and persistent bile leakage. In cases where the need for an existing drain is questionable, it is extremely important to remove it as soon as possible. “Dry” drainage for 24 hours indicates that it has served its role. Finally, Howard Kelly (1858-1943) said: “Drainage is the recognition of defective surgery.” Clinicians must be careful not to confirm this statement in practice: if it is safer to switch to an open procedure and carefully close the ultrashort cystic duct than to rely on questionable clip closure and safety drainage, then the choice is clear.

Recovery after laparoscopy

Surgeon of surgical department No. 1 Markevich E. V.

Laparoscopy is a low-traumatic surgical procedure. Since large incisions are not made, the regeneration time of tissues and organs is greatly reduced. But on the other hand, the endoscopic method of surgery involves the injection of gas into the abdominal cavity so that it is possible to obtain a sufficient overview during the necessary manipulations. And this affects the body and must be taken into account during the rehabilitation period.

After a routine uncomplicated laparoscopic operation, the patient is admitted to the intensive care unit, where he spends the next 2 hours of the postoperative period to monitor adequate recovery from the anesthesia state. In the presence of concomitant pathology or characteristics of the disease and surgical intervention, the duration of stay in the intensive care unit may be increased. The patient is then transferred to a ward where he receives the prescribed postoperative treatment.

During the first 4-6 hours after surgery, the following symptoms may appear: moderate nagging pain in the lower abdomen, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, frequent urge to urinate. These manifestations are considered normal and disappear after some time. Severe pain must be relieved. During this period, the patient should not drink or get out of bed. Until the morning of the next day after the operation, you can drink plain water without gas, in portions of 1-2 sips every 10-20 minutes with a total volume of up to 500 ml.

The patient can get up 4-6 hours after surgery. You should get out of bed gradually, first sit for a while, and, in the absence of weakness and dizziness, you can get up and walk around the bed. It is recommended to get up for the first time in the presence of medical personnel (after a long stay in a horizontal position and after the action of medications, orthostatic collapse - fainting) is possible.

The next day after the operation, the patient can move freely around the hospital, begin to take liquid food: kefir, oatmeal, diet soup and switch to the usual regime of drinking liquids.

For the first 7 days after surgery, the consumption of any alcoholic beverages, coffee, strong tea, drinks with sugar, chocolate, sweets, fatty and fried foods is strictly prohibited.

If there is a need during surgery, a drainage tube is placed, which allows the ichor to be drained. In the normal course of the postoperative period, the drainage from the abdominal cavity is removed the next day after surgery. Removing the drainage is a painless procedure; it is performed during dressing and takes a few seconds.

It is recommended to sleep on your back, and only if you feel well, there is no pain in the stitches, and if there is no drainage tube, you are allowed to sleep on your side. But lying on your stomach is prohibited.

Also in the postoperative period, especially the first two days, there may be discomfort in the throat: these are the consequences of the insertion of an anesthesia tube. There may also be pain in the cervical and shoulder regions, they are caused by the fact that during the operation there was pressure of carbon dioxide on the diaphragm.

In the first month after surgery, the functions and general condition of the body are restored. Careful adherence to medical recommendations is the key to full recovery of health. The main areas of rehabilitation are adherence to physical activity, diet, drug treatment, and wound care.

Compliance with physical activity regimen.

After surgery, it is recommended to limit physical activity for a period of 1 month (do not carry weights of more than 3-4 kilograms, exclude physical exercises that require tension in the abdominal muscles). This recommendation is due to the peculiarities of the formation of the scar of the muscular aponeurotic layer of the abdominal wall, which reaches sufficient strength within 28 days from the moment of surgery. 1 month after surgery there are no restrictions on physical activity.

Diet.

Compliance with the diet is required for up to 1 month after laparoscopic surgery. Heavy foods are prohibited: fatty, spicy, fried foods that are cooked in large quantities of vegetable oil or butter. It is necessary to avoid cooking with animal fat; pickled, smoked products, canned food; fatty meats, lard; fresh baked goods, confectionery, sweets, as these products cause increased gas formation in the intestines; legumes, which lead to flatulence; alcohol. Regular meals 4-6 times a day are recommended. New foods should be introduced into the diet gradually; 1 month after surgery, it is possible to remove dietary restrictions on the recommendation of a doctor.

Drug treatment.

Minimal medical treatment is usually required after laparoscopic surgery. Pain syndrome after surgery is usually mild, but some patients require the use of analgesics for 2-3 days. Taking medications should be carried out strictly as directed by the attending physician in an individual dosage.

Care of postoperative wounds.

In the hospital, special stickers will be applied to postoperative wounds located at the places where instruments are inserted. It is possible to take a shower wearing stickers with a protective film starting from 48 hours after surgery. It is better not to allow water to get into the seams. Taking baths or swimming in pools and ponds is prohibited until the stitches are completely healed. Usually taking a bath is allowed after 1 month.

Sutures after laparoscopic cholecystectomy are removed 7-10 days after surgery. This is an outpatient procedure, the sutures are removed by a doctor or a dressing nurse.

Any operation may be accompanied by undesirable effects and complications. Complications from wounds:

- Subcutaneous hemorrhages (bruises) that go away on their own within 7-10 days. No special treatment is required.

- There may be redness of the skin around the wound and the appearance of painful lumps in the wound area. Most often this is due to wound infection. If such symptoms appear, you should consult a doctor as soon as possible. Late treatment can lead to suppuration of the wounds, which usually requires surgical intervention under local anesthesia (debridement of the festering wound) followed by dressings and possible antibiotic therapy.

- In 5-7% of patients, hypertrophic or keloid scars may form. This complication is associated with the individual characteristics of the patient’s tissue reaction and, if the patient is dissatisfied with the cosmetic result, may require special treatment.

- In 0.1-0.3% of patients, hernias may develop at the sites of trocar wounds. This complication is most often associated with the characteristics of the patient’s connective tissue and may require surgical correction in the long term.

Physiotherapy

Physiotherapy after laparoscopy is aimed at restoring the functionality of tissues damaged during surgery. The features of physiotherapy depend on the purpose of the intervention and the organ being operated on. If laparoscopy was performed as a diagnostic method, then physical procedures are not performed, there is no need for them. Carrying out physiotherapeutic measures helps to soften connective tissue. As a result, pain is reduced and adhesions from laparoscopic procedures are eliminated

If you follow the doctor’s recommendations during the recovery period after laparoscopy, the patient’s rehabilitation will significantly speed up.

Drainage after omentopexy for perforated ulcer

If you have performed perfect suturing of a perforated ulcer with tomponade with an omentum, is drainage necessary? 80% of respondents said “no” (Table 5).

Table 5. Will you leave drainage after suturing a perforated ulcer with tomponade with a strand of omentum?

| Quantity | No (%) | Yes (%) | |

| North America | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| Western Europe | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 3 | 4 |

| Latin America | 15 | 13 | 2 |

| Asia | 15 | 9 | 6 |

| Australia | 3 | 3 | |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 71 | 57 (80%) | 14 |

Literature data is limited. Pai et al. [] in their message are the most informative. In the treatment of peritonitis, multiple drainage does not reduce the incidence of intra-abdominal fluid accumulation and abscess formation, nor does it improve postoperative results. Depressurization of the sutured hole was observed in 4 patients with drainage (5.3%) and 1 without drainage (2.3%). They all died. The wound around the drainage festered in 10% of patients. One required laparotomy to free a loop of small intestine that was twisted around a tube. Another developed bleeding from a drainage hole. Based on their own experience and literature data, Petrowsky at al found that “suturing a perforated ulcer with tomponade with an omentum is safe without prophylactic drainage; routine drainage cannot be recommended” (3).

Suturing with tomponade with an omentum, properly performed and tested by injecting colored liquid through a probe, prevents leakage. In addition, when leakage develops, the presence of a drain is not helpful (9). Duodenal lateral leakage is a very serious complication and is almost impossible to control with simple drainage. To stop, relaparotomy and gastric resection according to B-2 are indicated. or, at a minimum, transfer of the “side” duodenal fistula to the “end” one (Gastroenteroanastomosis + tubular duodenostomy, or disconnection of the duodenum). Excessive reliance on drainage when leakage has developed delays vital surgery and hastens death.

What can we say about laparoscopic suturing, an increasingly popular procedure? Does this change the indication for drainage? Leakage after omentopexy is so rare that even comparison of very large series of open and laparoscopic operations does not allow reliable conclusions to be drawn. However, surgeons who have used open omentopexy have alarmingly reported leakage rates of 6–16% after laparoscopic closure (10). This may be due to a “learning curve” - the inability to feel the tension of sutures and tissues, in particular the packing omentum. Therefore, the laparoscopic approach may be more prone to leakage from the sutured opening. I'm still amazed when I see drainage being used to prevent disaster. I find this unlikely. A surgeon who knows how to suture safely does not need drainage. But for a surgeon learning laparoscopic closure (with a small number of peptic ulcers, your learning curve can take forever) drainage may be allowed. It will not prevent reoperation if leakage has occurred. But it can provide early diagnosis when leakage requires re-intervention. However, a timely contrast study (with or without CT) will provide more information than an often poorly placed and unproductive drain.

Emergency colon surgery

Issues of drainage after emergency resection of a perforated sigmoid without or with primary anastomosis should be considered together. In both cases, control of the source of infection is provided by colectomy. The reason for drainage can be twofold - therapeutic (to help in the treatment of concomitant intra-abdominal infection) or prophylactic (to prevent the accumulation of fluid or to control the incompetence of the suture line of the anastomosis or rectal stump). About 60% of respondents (Tables 6 and 7) do not routinely drain the abdominal cavity in this situation.

The topic of drainage after left hemicolectomy with or without anastomosis has been discussed for 30 years. Proponents claim that drainage prevents reoperation in case of suture failure. Critics argue that the drainage itself causes failure. It is difficult to determine the validity of the 8 studies by Petrowsky et al. [], which included emergency and elective patients, with and without drainage. All 8 studies showed no difference in postoperative complications with or without drainage, but some authors reported a high incidence of wound infection with drainage. They talk about small advantages of not draining in relation to leakage. This confirms an earlier meta-analysis by Urbach et al. [], who concluded that “there is no significant benefit from routine drainage of intestinal or rectal anastomoses in terms of reducing the incidence of leaks or other complications.” The same authors reported that "20 observed leakages among all 4 studies that occurred in patients with drainage, in only 1 case (5%) did pus or intestinal contents actually appear through the drainage." Even overly cautious authors conclude that “there is insufficient evidence to show that routine drainage of colorectal anastomoses prevents anastomotic or other complications” (12).

Table 6. Do you place a drainage during the Hartmann operation against the background of cancer perforation or sigmoid diverticulum?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 15 | 3 |

| Western Europe | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 2 | 4 (1 did not operate on the intestine) |

| Latin America | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Asia | 15 | 6 | 9 |

| Australia | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 71 | 47 (66%) | 24 |

Table 7. Do you place drainage during colectomy and primary anastomosis due to cancer perforation or sigmoid diverticulum?

| Quantity | No | Yes | Comments | |

| North America | 18 | 14 | 3 | 1 (never performed primary anastomosis) |

| Western Europe | 10 | 5 | 5 | |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 2 | 3 | 1 (did not operate on the intestine); 1 (never performed primary anastomosis) |

| Latin America | 15 | 10 | 4 | 1 never performed a primary anastomosis) |

| Asia | 15 | 3 | 11 | 1 (never performed primary anastomosis) |

| Australia | 3 | 1 | 2 | |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | — | |

| Total | 71 | 43 (60%) | 28 |

The surgeon decides to drain in this situation for the following reasons:

1. Combating residual or preventing recurrent intra-abdominal infection by removing exudate or draining a peri-intestinal abscess discovered or already drained during the operation. The futility of such drainage in terms of achieving the stated goal has already been discussed in the section on acute appendicitis.

2. Drainage of the area of future possible anastomotic leak. However, the high risk and tendency of the anastomosis to depressurize are circumstances that are not suitable for anastomosis in an emergency situation. In addition, drainage does not help with leakage, not to mention the false sense of security in the absence of discharge through the drain (13). Only a pathological optimist can assume that feces will be released through the drainage and the tube will not become clogged with fibrin. In conclusion: drainage after emergency colon resection is a waste of time.

Drainage for diffuse peritonitis

With diffuse peritonitis, only a third of respondents drain the abdominal cavity (Table 8).

Table 8. Will you drain the abdominal cavity with diffuse peritonitis?

| Quantity | No | Yes | |

| North America | 18 | 17 | 1 |

| Western Europe | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 2 | 5 |

| Latin America | 15 | 12 | 3 |

| Asia | 15 | 5 | 10 |

| Australia | 3 | 2 | 1 (pelvis only) |

| South Africa | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 71 | 47 (66%) | 24 |

The distribution of answers here is identical to questions 3, 5, 6, 7. Asia and Eastern Europe believe in the value of drainage for local and diffuse intra-abdominal infection. There are no comparative studies of drainage and non-drainage in diffuse peritonitis, since the futility of drainage in this situation was established many years ago by experts in surgical infection. The modern view, presented by the Society for Surgical Infection, is formulated by Rotstein and Meakins []: “It is impossible to drain the abdominal cavity with generalized peritonitis. Therefore, the use of drainage in these patients is not indicated, except in cases where (1) drainage is used for postoperative lavage; (2) drainage is placed in the cavity of a well-confined abscess; (3) drainage is used to form a controlled fistula.”

I remember when I was a junior resident, post-op patients would have rubber drains sticking out of every quadrant of their distended abdomen. These tubes produced some old blood, or perhaps some pus or foul-smelling fluid. When such a patient died, the cause was often given as pneumonia. How stupid we were! We believed that these drainages could be useful! Gradually we came to the understanding that they were worthless: all intra-abdominal drainages became clogged with surrounding tissue within 24-48 hours.

The only indication for the use of drainage for generalized peritonitis is control over an uncontrolled (unremovable) source of infection, such as failure of the duodenal stump or esophagogastroanastomosis. I am skeptical about the term “well-confined abscess” or “formed abscess” as an indication for peritoneal drainage. Such abscesses accumulate pus and are part of diffuse peritonitis. Once evacuated, they should be treated as part of the infected abdomen, along with other peritoneal measures and antibiotic therapy. Of course, peritoneal lavage is a thing of the past.

In conclusion, it is important to understand that drainage for diffuse peritonitis is pointless. However, recurrent or persistent intra-abdominal infection may develop, requiring percutaneous drainage or reoperation. Drainage will not replace this. And the fact that you do not have a CT scan at hand should not change the indication for drainage, as will be shown below.

Obligate drainage

In what situations is drainage necessary? Each respondent answered this question according to his own understanding (Table 9). From a purely practical point of view:

1. In the first place, and this is true, is the possibility of leakage of bile or pancreatic juice. These fluids are easily collected and evacuated by drainage, which, when installed in cases of biliary and pancreatic leakage, can be life-saving and have a therapeutic effect.

2. The second indication is an abscess containing pus. Some surgeons believe that a well-formed cavity containing pus requires drainage. Many respondents attach importance to terms such as “undrained abscess” or “thick-walled abscess” as an indication for drainage. I'm surprised that such abscesses are actually found in the abdominal cavity!

3. The third general point is insufficient control over the source of infection. A variety of indications appear here, such as bile leakage, urination, the impossibility of forming a full-fledged external fistula of the duodenum or jejunum without an intermediate cavity, which is quite reasonable.

4. Difficult duodenal stump – danger of incompetence after gastric resection according to B-2.

5. Other situations such as the danger of urination, the danger of leakage of the esophageal suture line, which is also reasonable. Regarding the danger of possible bleeding, which, as a rule, is unnecessary and is rarely performed. Even with significant bleeding, this is just the tip of the iceberg.

Table 9. In what situation will you install drainage?

| Situations | Number of respondents | Comments | |

| 1. | High probability of leakage of bile or pancreatic juice | 37 | |

| 2. | Proven abscess containing pus | 31 | Many people attach importance to “thick walls” or “an abscess that has not collapsed” |

| 3. | Lack of satisfaction from complete “source control” | 11 | Some say: "when I expect expiration" |

| 4. | Difficult duodenal suture line | 6 | |

| 5. | High chance of urine leakage | 4 | |

| 6. | Esophageal suture line | 2 | |

| 7. | Expected bleeding | 3 | Typically drain for 24-48 hours |

How to prepare for a doctor's appointment?

Contact your family doctor or general practitioner if you have stomach pain. If you have appendicitis, you will likely be admitted to surgery to have your appendix removed.

Questions the doctor may ask you! To find out the cause of your abdominal pain, your doctor will likely ask you a series of questions, such as:

- When did the abdominal pain start?

- Where does it hurt?

- Did the pain move?

- How severe is the pain?

- What makes the pain worse?

- What helps relieve pain?

- Do you have a fever?

- Do you feel nauseous?

- What other signs and symptoms do you have?

Questions you can ask your doctor:

- Do I have appendicitis?

- Do I need to undergo examinations?

- What else could cause the pain?

- Do I need surgery and if so, how soon?

- What are the risks of the operation?

- How long will I need to stay in the hospital after surgery?

- How long does recovery take?

- How soon after surgery can I return to work?

- What if my appendix ruptures?

Feel free to ask other questions.

Diagnostics ! To diagnose appendicitis, the doctor will examine your complaints and symptoms, conduct a general examination and examine your abdomen. Tests used to diagnose appendicitis include: Abdominal examination. The doctor will apply light pressure to the painful area of the abdominal wall and then release the hand. If the pain intensifies, this indicates inflammation of the peritoneum of the appendix (peritoneal symptoms). The doctor also examines the presence of tension in the abdominal wall muscles during palpation (muscle defence), which also indicates the presence of an inflammatory process in the abdominal cavity. The doctor will also perform a digital rectal examination. To do this, he will put on a sterile glove and generously lubricate it with Vaseline and insert his index finger into the patient’s anus. Women of childbearing age should have a gynecological examination to rule out possible gynecological problems that may be causing abdominal pain. Blood analysis. Allows your doctor to detect elevated white blood cell levels, which may indicate an infection. Analysis of urine. Your doctor may ask you to have your urine tested to make sure your stomach pain is not caused by a urinary tract infection or kidney stones. Imaging studies. Your doctor may also recommend an abdominal x-ray, abdominal ultrasound, or computed tomography (CT) scan to confirm appendicitis or look for other causes of your pain.

Treatment ! Treatment for inflamed appendicitis usually requires surgery. Before surgery, you may be given a one-time antibiotic to prevent infection. Surgery to remove the appendix (appendectomy). Both an open appendectomy using a single abdominal incision 5 to 10 centimeters long (laparotomy) on the anterior abdominal wall, and a laparoscopic one using several small incisions are performed. During a laparoscopic appendectomy, the surgeon inserts special surgical instruments and a video camera into the abdominal cavity to remove the appendix. In most cases, after laparoscopic interventions, patients have a shorter rehabilitation period, less postoperative pain and less scarring. This method is more suitable for elderly or obese people. However, if the appendix perforates and the infection spreads through the abdomen (peritonitis) or an abscess forms, you may need an open appendectomy, which allows your surgeon to debride the abdomen. After your appendix is removed, you will have to spend one or two days in the hospital.

Drainage of appendiceal abscess! If an appendiceal abscess has formed, to drain it, a drain is placed into the abdominal cavity through an opening in the anterior abdominal wall. A few weeks after the abscess has been drained, the appendix can be removed. Lifestyle changes and home treatment! Recovery from an appendectomy will take several weeks. If the appendix ruptures and peritonitis develops, recovery will be longer.

How to drain?

The authors' answers are very varied, especially taking into account the different manufacturing companies. Most indicate that drainage can be active (a round tube connected to a suction) or passive (a tube or flat drain operated by gravity). Table 10 shows that 60% of respondents prefer “active” drainage. North Americans prefer active drainage exclusively. Others use mixed drainage - tubular, wrinkled or Penrose drainage.

Which drainage is better? The different types of drains and their characteristics have been described in detail by O'Connor and Hugh []. It is desirable that the drainage be soft and elastic to minimize the real danger of compression necrosis of the intestine or its mesentery. Passive drainage works due to capillarity, gravity or pressure difference. Active drainage is connected to suction. Passive drainage is considered as an open system, which is associated with contomination of the wound drainage channel due to the retrograde spread of bacteria on the skin surface (“drainage drains in both directions”). Many authors believe that passive drainage is not effective in the upper abdominal cavity due to the negative intrathoracic pressure that occurs during breathing (1), others disagree (15).

Active drainage tends to become clogged with aspirated tissue or clots. High suction pressure blocks drainage. Double-lumen drainage is more resistant to blockage, but it usually consists of a rigid material and does not provide safety during prolonged standing in the abdominal cavity. Interestingly, a study of drainage after cholecystectomy showed that simple passive drainage was 2 times more effective than simple active suction drainage, and double-lumen drainage was more effective than passive one (15).

Flat and soft active are the only drains I use in the abdominal cavity, usually in rare cases of complex cholecystectomy. I will use these same drains in other situations, for example, when expecting a biliary or pancreatic fistula. Surgeons who use active drainage know that after a few hours it becomes clogged with fibrin and pus. And open passive drainage will act as a one-way highway (inward) for skin bacteria. As for surgeons who leave a drain near the colonic anastomosis, I would be surprised to learn that they rely on a tubular active drain to aspirate the feces. To remove it, a large passive tube (wrinkled drainage) with a significant (2 fingers) incision in the skin and abdominal wall is required. But in this case, complications such as a drainage hernia, acute intestinal obstruction, bleeding and abscess of the drainage canal are possible. For various drainage complications, see table. eleven.

Table 11. Complications of intra-abdominal drainage and their prevention.

| Complications | Complications |

| "Drainage temperature" | Loss of drainage (slipping under the fascia or breaking) |

| Drainage channel infection | |

| "Drainage hernia" | "Lost drainage": migration into the abdominal cavity or "fragmentation" |

| Bleeding from the drainage channel | |

| Intestinal obstruction | Contamination of sterile tissues |

| Gut erosion | Obstacle to fistula healing |

These complications are real. Some are rare. But I have experienced each of them during the “dark period” of my career. Many can be prevented by careful handling of drains (Table 12), but the best way to prevent drainage complications is to avoid them when drainage is not indicated. The majority of residents indicate that they now drain the abdominal cavity less frequently than they previously did during the initial period of their surgical career (Table 13).

Table 12. Installation and management of drains

Introduction of drainage

- I choose the appropriate drainage according to the situation, but in general the softest and smallest in diameter.

- I install it strictly in the required area, trim the excess length, but leave it with some sagging.

- I place drainage away from the intestinal wall or vessels

- I try to place the omentum between the drainage and vital structures to avoid erosion

- I place the drain away from the main wound to prevent wound infection.

- I plan the shortest route for drainage placement, depending on the indications and type of drainage.

- When suturing the main wound, do not catch the drainage into the suture without fixing it to the fascia.

- Fix the drainage to the skin using a suture.

Control

- I use a closed system whenever possible

- I use low vacuum to prevent suction of nearby tissues to the drainage hole

- I take care of small-diameter tubes by rinsing them twice a day with a small amount of saline solution under sterile conditions.

- When a fistula has formed (eg, a biliary fistula), suction should be stopped and passive drainage by gravity should be used.

Removal

- I remove the drainage as soon as it stops working or performing its preventive function.

- Removal of long-standing drainage should be carried out in stages, “step by step” to prevent the formation of deep interstitial abscess

- Removal or shortening of the drainage can be carried out under ultrasound and CT control.

- If the drain is shortened, it must be reattached to the skin to prevent proximal migration.

Table 13. Do you drain more often now than at the beginning of your career?

| Quantity | Less or much less | More or also | |

| North America | 18 | 18 | |

| Western Europe | 10 | 7 | 3, "Never in Large Numbers" (1) |

| Eastern Europe | 7 | 6 | 1 |

| Latin America | 15 | 15 | |

| Asia | 15 | 13 | 2 |

| Australia | 3 | 3 | |

| South Africa | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 71 | 67 (95%) | 4 |

Symptoms!

Subjective and objective symptoms of appendicitis include:

- Sudden pain in the lower right abdomen

- Sudden pain that occurs around the belly button and often moves down and to the right

- Pain that worsens with coughing, walking, and sudden movements

- Nausea and vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Low-grade fever, which may increase as the disease progresses

- Constipation or diarrhea

- Bloating

- The location of pain may vary depending on age and position of the appendix. During pregnancy, pain from appendicitis is localized higher because the appendix moves higher during pregnancy.

Geographical differences in practice

Surgeons in North America tend to limit the use of drains for most indications, while surgeons in Asia and Eastern Europe are enthusiastic about drains. This primarily applies to diffuse peritonitis and emergency colon surgery. Today we have the right to ask why surgeons in North America, as well as Western Europe and Latin America, place less drainage? This is influenced by several factors:

- With the improvement of surgical techniques, the effectiveness of antibiotics, and the improvement of image quality at the diagnostic stage and after surgery, the results of emergency operations have improved. Surgeons began to encounter fewer and fewer complications that drainage could prevent. Why drain if it is not necessary?

- The availability of CT scans has also given surgeons more confidence. The mysterious postoperative abdominal cavity is no longer a “black box.” There is no longer a need to rely on drainage to alert you to the development of an abscess.

- The great success of image-guided percutaneous drainage of intra-abdominal collections and abscesses has added confidence to surgeons that there is no need for thick tubes for many days to clear an abscess.

- Modern surgeons understand that there is no need for drains to “prevent and treat” persistent or recurrent infection after, say, perforated appendicitis. They teach that most patients will be fine after removal of the source (appendectomy) and antibiotic therapy. And if not, CT and percutaneous drainage under CT guidance will help them.

There remains the question of the continuing enthusiasm for drainage in Asia and Eastern Europe. Perhaps the lack of availability of CT in developing countries forces surgeons to continue to rely on drains. Or they are more subject to local dogmas, reinforced by strict discipline. The latter seems very likely. In my practice, we stopped routine use of drains in the mid-1980s, long before the advent of CT scanning and percutaneous drainage. However, we already understood what surgeons know today: with or without CT, many drains are unnecessary and counterproductive. We are reminded of the words of William Stewart Halsted: “Not having drainage is better than installing it illiterately.”

To speed up the recovery process after surgery:

- Avoid physical stress. If your appendectomy was performed laparoscopically, limit activity for three to five days. If you have had an open appendectomy, limit your activity for 10 to 14 days.

- Always ask your doctor about expanding your regimen, exercising, and returning to work.

- Support your stomach when you cough. Place a pillow on your stomach and apply pressure before coughing, laughing, or moving to relieve pain.

- Tell your doctor if pain medications do not help. Pain is an additional stress for the body and slows down the healing process. If you still experience pain despite taking painkillers, tell your doctor.

- Get up and move when you're ready. Start expanding your regimen slowly and increase your activity gradually. Start with short walks.

- Sleep if you feel tired. After surgery, you may feel drowsy. Calm down and rest when you need to.

- Discuss returning to work or school with your doctor. You can return to work when you feel stronger. Children can return to school in less than a week after surgery. However, it should take two to four weeks before you can return to vigorous activities, such as playing sports.