Diagnostics

In the diagnosis of esophageal rupture, data from the anamnesis, as well as a number of instrumental and physical studies are considered:

- plain chest x-ray;

- abdominal x-ray;

- X-ray of the esophagus using a water-soluble contrast agent;

- If necessary, pharyngoscopy, mediastinoscopy, and esophagoscopy are prescribed.

- During diagnosis, it is very important to exclude other pathologies that may have similar symptoms: myocardial infarction, peptic ulcer, attack of acute pancreatitis, etc. For this purpose, if necessary, ultrasound examination of the aorta, echocardiography, ultrasound examination of the pleural cavities, laparoscopy and other studies can be performed.

You must make an appointment with a surgeon.

Esophageal rupture: symptoms and consequences

15.09.2021

Most often, it is not external injuries that are dangerous, but internal ones, which are not only difficult to notice, but also not always possible to cure, given that time in most cases is severely limited.

The main reason is the abundant blood supply, since even a minor injury, due to which the organ itself does not fail, can lead to large blood loss and, accordingly, death.

Esophageal rupture is considered just such damage. During it, partial or complete damage occurs, or rather a rupture of the walls of the esophagus , which causes severe internal bleeding and shock occurs. If help is not provided on time, death is possible within a few hours.

How does an esophageal rupture appear and feel?:

• the chest may appear the chest , which will feel like pain in the abdomen . • Body temperature rises quite sharply, but the person may feel chills. Nausea may occur , accompanied by blood discharge. • Shock appears and heart rate increases.

A rupture can only be treated by surgical intervention, without which the person simply dies due to massive bleeding. In order to detect and diagnose the problem, an X-ray of the chest and esophagus , tomography, ultrasound and medical history are performed.

Why the intestines can rupture:

- If there is a penetrating wound in the chest or a serious injury (stroke) has been received

- Frequent and severe vomiting, regardless of its cause

- The occurrence of malignant tumors, due to which the walls of the esophagus simply become thinner and cannot withstand the usual load

- When eating large amounts of food

- Due to strong and frequent bowel movements

- Damage to the esophagus during examination (with instruments). In most cases, it occurs solely due to doctor

- During heavy lifting and just intense physical activity

How does this threaten a person:

- A person cannot swallow and crush food normally.

- Bleeding may remain or periodically occur.

- A variety of types of inflammation begin, which subsequently develop into a variety of diseases.

- Greater susceptibility to infections.

- Sepsis and abscess are possible.

- The heart muscle may be damaged.

- There is a high probability of severe shock.

- Death due to lost time or poor medical care.

If a person suspects he has a similar problem, then he should immediately call an ambulance, while the body should almost always be in a sitting position, and something cold can be applied to the possible area of damage so that the bleeding decreases slightly. Until the exact problem is identified, it is forbidden to eat food or perform heavy physical activity.

The problem is very dangerous and if there is a possibility of a rupture of the esophagus , then you need to lead a very careful lifestyle, as well as undergo periodic examinations.

Published in Surgery Premium Clinic

Treatment

As a rule, treatment for a rupture of the esophagus is only possible through surgery, although for fresh injuries of the laryngeal part of the esophagus, conservative therapy can also be prescribed. Surgery can also be avoided if the esophageal wall is not completely ruptured. In such situations, the patient must be hospitalized, prescribed painkillers and antibacterial drugs, and completely exclude oral nutrition. If the patient's well-being worsens, urgent surgical intervention is performed.

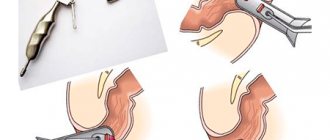

If the patient is diagnosed with a rupture of the cervical esophagus, a cervical mediastinotomy is performed and a double-lumen drainage is installed. If the thoracic esophagus is damaged, if no more than a day has passed since the rupture, surgeons perform a thoracotomy, the defect is sutured and covered with a pleural flap. If more time has passed since the injury, the esophagus is not sutured, but palliative measures are taken:

- gastrostomy;

- drainage of the pleural cavity;

- mediastinotomy;

- esophagostomy, etc.

- Esophageal rupture is a violation of the integrity of the wall of the esophagus, which occurs as a result of injury or spontaneously.

The first reliable description of spontaneous esophageal rupture (SRU) is associated with the name of the Dutch surgeon Hermann Boerhaave (1668-1738), who in 1724 described in detail the rupture of the esophagus during vomiting after ingesting large amounts of food and liquid, which in turn was the impetus for its subsequent in-depth and detailed study. Boerhaave's syndrome is a spontaneous rupture of the esophagus. In the literature there are many synonyms for this disease: spontaneous rupture, non-traumatic rupture, post-vomiting rupture of the esophagus, “banquet” syndrome, etc. [4, 12, 33, 35].

H. Boerhaave described an extremely rare variant of esophageal rupture, namely transverse, while in most cases there is a longitudinal esophageal rupture, first described by A. Dryden in 1788, and K. Myers (1858) gives priority to its intravital diagnosis, with the first a case of recovery of a patient with Boerhaave's syndrome due to drainage of the pleural cavity was described by N. Frink in 1947 [4, 23].

ERP most often affects the adult population, mainly men (85-90%) aged 50-60 years, since the resistance of the walls of the esophagus weakens with age (in childhood, the esophagus withstands pressure 4 times more than in adults), while At the same time, cases of SRP in younger patients have also been described in the literature [19, 20, 24].

An increase in intraesophageal pressure that occurs during gagging is considered one of the main factors in the development of Boerhaave's syndrome, while aggravating factors, according to the unanimous opinion of most researchers, are overeating and alcoholism [21, 29, 30, 35].

During the urge to vomit, there is a sharp tension in the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, contraction of the diaphragm, the muscular lining of the stomach with the simultaneous opening of the esophagocardial sphincter, but with the pharyngeal-esophageal sphincter closed, which leads to a sharp increase in pressure in the lumen of the esophagus (according to the literature, the pressure at the border of the esophagocardial sphincter can reach 200 mmHg). A similar mechanism of SRP is confirmed by the experimental data of R.A. Sulimanova et al. (2004) and M. Makloul (2006).

SRPs are characterized by the occurrence of large wall defects (from 4-5 to 10-12 cm) and are most often localized on the left wall of the lower thoracic esophagus [20].

In most cases (up to 95%), esophageal ruptures are oriented longitudinally and are localized in the weakest section (3-6 cm above the diaphragm). It should also be noted that in the pathogenesis of spontaneous rupture of the esophagus, the structural feature of the muscle fibers of the left wall of the lower middle section of the esophagus, which determines the least resistance to rupture in this area, also plays a certain role. In this zone, the muscle fibers of the circular layer are defective due to the entry of nerve trunks and blood vessels [20, 24, 32, 34]. Morphological changes in the wall of the esophagus that precede SRP are described in detail in the work of A.A. Sapozhnikova, M.M. Abakumov and A.N. Pogodina (1975) and are characterized by restructuring of the mucous membrane in the form of leukoplakia and hyperplasia of the mucous glands, hypertrophy of the muscle fibers of the mucous membrane and restructuring with atrophy of part of the fibers of the circular layer, which contribute to the occurrence of wall rupture under conditions of increased intracavitary pressure with preserved tone of the lower esophageal sphincter.

In Boerhaave's syndrome, the magnitude of the muscle membrane rupture always exceeds the magnitude of the mucosal defect. Often there is a combined damage to the wall of the esophagus and the mediastinal pleura, resulting in communication of the lumen of the latter, as a rule, with the left pleural cavity [18, 27, 35].

There is information about a certain role in the occurrence of PSA of hiatal hernia, gastritis, esophagitis, varicose veins of the esophagus, eosinophilic esophagitis (several reports have been published on this rare disease complicated by PSA), which does not manifest itself in any way before rupture [3, 11, 22 , 27, 32, 35]. However, the role of the above diseases in the occurrence of PSA has not been fully studied.

Currently, Boerhaave's syndrome is considered as a symptom complex consisting of vomiting, severe pain in the upper abdomen or lower chest extending to the interscapular region, difficulty breathing, painful swallowing, shock and intoxication. The latter is caused by the entry of food and esophageal contents into the mediastinum and into the pleural cavity [3, 4, 11, 20, 28]. In the first hours after perforation, as a rule, pain symptoms of uncertain localization predominate; later, signs of purulent intoxication, mediastinitis and pleurisy come to the fore. In this case, among the general symptoms, pallor and cyanosis of the skin, cold sweat, shortness of breath, tachycardia, chills, and hyperthermia may dominate [18, 22, 26, 30].

The acute onset of PSA, accompanied by sudden chest pain and shock, can mimic myocardial infarction, as well as perforated gastric and duodenal ulcers, which in turn can be a reason for unsuccessful laparotomy. Often, PSA must be differentiated with acute infarction and acute pancreatitis, less often with dissecting aneurysm, diaphragmatic hernia, spontaneous pneumothorax, spontaneous mediastinal emphysema, and pharyngeal rupture [4, 7, 14, 28, 31].

Establishing a timely and correct diagnosis in SRP is the most important and at the same time one of the difficult and not fully resolved problems [3, 7, 16, 24, 29]. Early detection of esophageal damage and subsequent surgical intervention are one of the main success factors in the treatment of this category of patients [7, 16, 31, 34].

Diagnosis of PSA, according to the literature, is based on an assessment of the clinical picture and the use of X-ray examination (plain X-ray of the chest, as well as contrast study of the esophagus, stomach), X-ray computed tomography (CT) and endoscopic examination (fibroesophagoscopy) [3, 6, 8, 15 , 23, 27].

X-ray examination is recommended to begin with survey fluoroscopy and radiography without the use of contrast agents in order to detect gas and liquid in the mediastinum and pleural cavities, as well as soft tissues of the neck. Then, regardless of the results of a non-contrast study, contrasting of the esophagus should be performed, which makes it possible to establish the location of the rupture and the presence of a cavity in the mediastinum [1, 13, 23].

In contrast radiological methods of studying the esophagus, the absolute criterion for a rupture of its wall is the flow of the contrast agent beyond the contours of the esophagus, as well as the deposition of the contrast agent in the pleural cavity [2, 16, 17, 25, 33].

As for such objective research methods as ultrasound, CT, their use is limited to a small number of observations [20, 22, 27] and CT semiotics in SRP has not been developed in detail.

Some authors recommend draining the corresponding pleural cavity, which allows one to suspect and establish damage to the esophageal wall [34].

Fibroesophagoscopy makes it possible to assess not only the volume and nature of the rupture, but also concomitant diseases of the upper digestive tract [28, 31], however, this study can lead to rupture of the mediastinal pleura, tension pneumothorax and acute cardiopulmonary failure. For preventive purposes, it is recommended to pre-drain the pleural cavity [16, 21, 26].

Despite the fact that about 90% of patients with SRP seek medical help in the first hours, surgical intervention is often performed late due to late diagnosis [7, 14, 34]. According to a number of researchers, a delay in the provision of surgical care for more than 24 hours increases mortality by 2 times, and the number of postoperative complications by 2.5 times [9, 14, 18].

PSA poses a real threat to the patient's life. Thus, mortality in SRP at the prehospital stage is 75%, postoperative - 25-85% and depends on the time from the moment of esophageal rupture to surgical intervention and the development of complications [13, 21, 31, 34]. Also, multiple organ failure and protein-energy imbalance are called one of the main and immediate causes of death in SRP [25, 28]. According to R. Brauer et al. (1997), on the 1st day without treatment, 65% of patients die, by the end of the 3rd day - already 100%.

When choosing treatment tactics for SRP, some authors give preference to drainage operations [19, 26], while others believe that the prognosis is significantly improved by suturing the esophageal defect [4, 16, 28].

Today, a number of authors consider the method of choice for rupture of the esophagus to be a suture on the defect of its wall [29, 32, 34], however, such tactics have fully justified themselves only in the early stages from the moment of rupture [19, 21, 28, 30]. In the later stages, the problem of suture failure as a source of persistence and progression of purulent mediastinitis arises [26, 31, 34]. The fundoplication cuff helps seal the sutures of the esophagus, prevents reflux of gastric contents, providing optimal conditions for healing of the wall defect [3, 5, 23, 28].

In the case of extensive ruptures (more than 5 cm), multiple defects of the esophagus, their combination with active esophageal bleeding, as well as if necrotic changes in the esophageal wall are detected, resection of the thoracic esophagus is indicated. In the postoperative period, active drainage of the mediastinum and pleural cavities is carried out. In order to relieve the esophagus and provide enteral nutrition, a gastrostomy tube is formed, through the lumen of which a probe is passed into the small intestine to provide enteral nutrition. Carrying out intensive pathogenetic corrective therapy during surgery and in the early postoperative period is an important part of the surgical treatment of patients [3, 16, 32, 35].

For SRP, various minimally invasive surgery methods are used [23, 26, 31]. S. Landen et al. (2002) in a work based on an analysis of literature and their own data, indicate that the range of minimally invasive surgery for SRP is quite wide and includes thoracoscopy, mediastinoscopy, laparoscopy, endoscopic installation of metal stents and endoscopic clipping. According to the authors, these treatment methods can be successfully used as an alternative to surgery and, thanks to their use, severe thoracic interventions with their complications and high mortality due to sepsis can be avoided [20, 25, 29].

Complications of PSA are mediastinitis, pleural empyema, pericarditis, sepsis, abscess pneumonia, arrosive bleeding from mediastinal vessels, esophagomediastinopleural, bronchopleural fistulas [5, 9, 10, 23, 28]. Their early diagnosis is extremely important.

The results of treatment with SRP remain disappointing due to the rapid development of purulent mediastinitis with severe septic manifestations [26, 28]. Even with timely treatment, multiple purulent-infectious complications can appear in the first 8-10 hours and serve as the main cause of death for the patient [21, 27, 33]. In such situations, the tactics of surgical treatment largely determines its outcome [20, 24, 34, 35].

Thus, an analysis of domestic and world literature indicates that the issues of diagnosis and treatment of spontaneous esophageal rupture and its complications remain largely unresolved.

Literature and sources

- Zabrosaev V.S., Sokolov V.N., Minchenkov V.L., Pysanka V.V. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Russian) // Bulletin of the Smolensk State Medical Academy. - Smolensk: Smolensk State Medical Academy, 2012.

- Miroshnikov B. I., Labazanov M. M., Ananyev N. V., Bely G. A., Smirnova N. A. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (Russian) // Bulletin of surgery named after I. I. Grekov. - St. Petersburg: Aesculapius, 1998.

- Tamulevichute D.I., Vitenas A.M. Spontaneous rupture of the esophagus (SRP) // Diseases of the esophagus and cardia. — 2nd edition, revised and expanded. - M.: Medicine, 1986.

Epidemiology

Spontaneous ruptures of the esophagus are a rare disease; they account for 2-3% of all cases of esophageal injury. Among all patients of the specialized department of thoracic surgery, spontaneous ruptures of the esophagus are detected in 0.25%. They most often occur in men over 50 years of age. 40% of the patients abused alcohol. The medical literature describes isolated cases of spontaneous rupture of the esophagus in newborns (I. Aaronson et al., 1975), but this disease practically does not occur in children over one year of age and adolescents.

Pathological anatomy

Spontaneous ruptures of the esophagus are characterized by the occurrence of large defects in the wall of the esophagus (from 4-5 to 10-12 cm) and are most often localized in the left wall of the lower thoracic esophagus (in 90% of cases). In the vast majority of observations, ruptures of the esophagus are oriented longitudinally and are localized in its weakest section - the left wall of the epiphrenic ampulla of the esophagus - directly above the diaphragm (3-6 cm above it); Injuries to the cervical, midthoracic and abdominal parts of the esophagus are extremely rare; sometimes the rupture extends to the stomach and looks like a gap in the esophagogastric junction. The conducted studies revealed structural features of muscle fibers in the left wall of the lower thoracic esophagus, which determine the lowest resistance to rupture in this place, which was confirmed in an experiment carried out on human cadavers by simulating an increase in intraesophageal pressure. With Boerhaave's syndrome, there is a rupture of all the walls of the esophagus (transmural rupture), in contrast to Mallory-Weiss syndrome, in which ruptures of the mucous membrane of the abdominal esophagus and the cardia of the stomach caused by profuse vomiting are superficial; in addition, ruptures in Boerhaave syndrome are rarely accompanied by massive bleeding. In case of spontaneous rupture of the esophagus, the magnitude of the rupture of the muscular membrane always exceeds the magnitude of the defect in the mucous membrane. In most cases, the mediastinal pleura is simultaneously damaged, resulting in a communication, usually with the left pleural cavity, which leads to the rapid development of pleural empyema. The entry of stomach contents into the mediastinum and pleural cavities leads to severe intoxication and high mortality.

Clinical picture

The classic picture of Boerhaave syndrome is characterized by the Mackler triad:

- vomiting of eaten food (in some patients there is an admixture of blood in the vomit);

- subcutaneous emphysema in the cervicothoracic region due to the accumulation of air in the subcutaneous fatty tissue (in 15%-30% of patients);

- severe cutting pain in the chest (less often in the abdomen), suddenly occurring during an attack of vomiting (may resemble pain from a stomach and duodenal ulcer), which can radiate to the left shoulder girdle and left lumbar region and increases with swallowing.

In most cases, the syndrome is manifested by shortness of breath, symptoms of shock (pallor, sometimes cyanosis, dilated pupils, weak pulse, profuse sweat, cold extremities, thirst, feeling of fear), abdominal pain, often in the epigastrium. In the first hours after perforation, pain symptoms of uncertain localization dominate; in some patients with symptoms of an “acute abdomen”, later signs of purulent intoxication, mediastinitis, and pleurisy begin to predominate.

Depending on the clinical and anatomical features, some authors distinguish 2 variants of spontaneous rupture of the esophagus: thoracic (caused by perforation of the thoracic esophagus, clinically manifested by pneumothorax, pneumomediastinum, and later purulent mediastinitis and pleural empyema) and abdominal (caused by rupture of the abdominal esophagus, clinically manifested by picture of peritonitis).

Quite often, diagnostic errors are made with Boerhaave's syndrome: spontaneous rupture of the esophagus, due to the rarity of this surgical disease, the variety of clinical manifestations, often simulating various pathologies of other organs, and the ignorance of most doctors, is mistaken for other diseases, most often for a perforated gastric or duodenal ulcer intestines, less often - acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, dissecting aortic aneurysm and acute pancreatitis.

Etiology and pathogenesis

A predisposing factor for spontaneous rupture of the esophagus may be changes in the muscular layer of the esophageal wall (drug-induced esophagitis, peptic ulcer of the esophagus against the background of gastroesophageal reflux disease, infectious ulcers in patients with AIDS), and the immediate cause is a sudden increase in pressure inside the esophagus with a closed pharyngeal-esophageal sphincter in combination with negative intrathoracic pressure, which occurs in the following pathological conditions:

- intense vomiting after a heavy meal, liquid and/or alcohol consumption (pressure in the stomach during vomiting can increase to 200 mm Hg), as well as with eating disorders such as bulimia;

- repeated vomiting due to dysfunction of the vomiting center at the bottom of the fourth ventricle of the brain;

- an increase in intragastric and then intraesophageal pressure when lifting heavy weights, straining during bowel movements, intense coughing, childbirth, or an epileptic attack.

A conscious desire to prevent vomiting in a public place, for example at a banquet table (“banquet esophagus”) can contribute to a sharp increase in intraesophageal pressure.

The typical location of a rupture of the esophagus in Boerhaave's syndrome (marked by an arrow) is the left wall of the lower thoracic esophagus directly above the diaphragm. Designations: 1 - thoracic esophagus, 2 - diaphragm, 3 - abdominal (abdominal) esophagus, 4 - stomach