Esophageal stenosis is a decrease in the diameter of the lumen of the esophagus due to scar, tumor, traumatic or other origin, leading to disruption of its normal patency. Medical practice shows that esophageal stenosis is an insidious disease. This pathology occurs in children and adults. The esophagus, in its physical characteristics, is a tube connecting the pharynx and stomach. With stenosis, the diameter of this tube decreases in certain areas. In such a situation, swallowing food becomes difficult. To prevent the development of the disease, you need to consult a doctor so that he can prescribe diagnosis and treatment.

Esophageal stenosis: what is it?

The esophagus is located at the level of the 6th cervical-11th thoracic vertebra. This is a narrow tube between the pharyngeal ring and the stomach, consisting of striated and smooth muscles, hollow inside. Its length is about 25 cm , normally the diameter of the lumen is 2-3 cm .

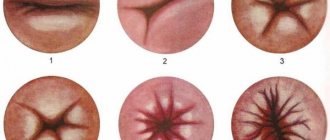

At the junction with the stomach, the squamous epithelium of the esophageal mucosa passes into the columnar epithelium of the stomach. This area is called the gastric rosette or Z line of the esophagus. During endoscopic examination, wave-like peristalsis is often noticeable.

As a result of various reasons, the lumen of the tube decreases, stenosis of the esophagus occurs, the code according to ICD 10 is as follows: esophageal obstruction according to ICD 10 is classified by code Q 39.3.

Causes

Experts classify esophageal stenosis into congenital and acquired. In children, pathology can manifest itself already in the first days after birth. In this case, the causes of stenosis lie in the peculiarities of embryonic development. In people who have passed the age of breastfeeding, the disease occurs for many reasons. This phenomenon occurs as a result of injury to the gastrointestinal tract or the entire abdominal cavity, as a result of the development of a benign or malignant tumor, as well as after previous surgical operations (in such cases, scars may remain in the gastrointestinal tract).

Classification

By degree of damage:

- affecting only the surface, without the formation of ulcerative areas;

- with the formation of defects and necrotic areas throughout the entire thickness of the mucosa;

- with damage to the submucosa.

With the flow:

- spicy;

- chronic.

By location:

- proximal;

- average;

- distal;

- combined.

If only one zone of the esophagus is narrowed, they speak of a single narrowing. If several sections are affected, multiple pathological changes occur.

You may be faced with a diagnosis of subcompensated esophageal stenosis. Subcompensated esophageal stenosis should be treated under the guidance of a doctor.

Degrees of esophageal stenosis:

- first degree - at the narrowest point the diameter of the tube is 11-9 mm , a medium-sized endoscope passes through;

- second degree - the lumen narrows from 6 mm to 8 mm .

- third degree - the diameter of the esophageal tube in the narrowed area is no more than 3-5 mm , the area can be examined with an ultra-thin fiberscope.

- fourth degree - the lumen narrows to a diameter of 1-2 mm or is completely blocked, that is, it becomes inaccessible even for a super-thin fiber endoscope.

One possible diagnosis is congenital esophageal stenosis.

Etiological factors

What are the causes of narrowing of the esophagus? 10% of all stenoses are congenital pathologies. They are caused by intrauterine malformations of the fetus. The muscular membrane of the hollow tube at the stage of formation can hypertrophy, fibrous rings can form in the cartilaginous wall, and the mucous membrane can form thin membranes.

The remaining 90% of narrowings are acquired by a person during life, including cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus and Shatsky’s ring.

What are the reasons for this?

There are a whole range of them:

- erosive and ulcerative reflux esophagitis;

- hiatal hernia;

- severe infectious esophagitis ;

- chemical burn of the esophageal tube;

- foreign body injury;

- post-surgical inflammation and scars ;

- candidiasis or other mycotic (fungal) infections;

- malignant or benign neoplasms.

Sometimes situations arise when pathology develops not in the esophageal tube itself, but outside it. In such conditions, the tube is compressed from the outside by enlarged lymph nodes, tumors in the mediastinum, and aortic aneurysm.

One of the priority areas of scientific research and practical activities of the endoscopic department of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery named after. acad. B.V. Petrovsky RAMS since its creation in May 1986 has been endoluminal endoscopic surgery of the esophagus. The urgent need for its development was due to the active surgical position of the Department of Esophageal and Gastric Surgery, which has existed in the Surgery Center since its opening in 1963. Over a period of more than a quarter of a century, we have accumulated experience in the endoscopic treatment of 844 patients with benign cicatricial strictures of the esophagus and esophageal anastomoses. The research results, including the tactics for managing this category of patients developed and recommended for wide clinical use, the technique of performing and approaches to choosing the method of endoscopic interventions, ways to prevent complications, have been published many times and reported at various Russian and international scientific forums [1, 4-14].

At the same time, the continued use in medical institutions of the country of blind bougienage, leading to a large number of esophageal perforations, illiterate and uncontrolled use of esophageal stenting in this category of patients, resulting in severe complications requiring serious surgical treatment, lack of experience in endoscopic treatment of severe (from 3 to 5 mm - III degree) and critical (less than 3 mm - IV degree) stenoses of the esophagus and anastomoses, including in most institutions dealing with this problem, necessitated the need to re-discuss this topic with an emphasis on the methodological aspects of endoscopic interventions.

During the period from May 1986 to May 2012, endoscopic interventions for scar narrowing of the esophagus were performed in 526 patients (283 men, 243 women) aged 16 to 90 years. Of this number, 280 (53.2%) had burn stenoses, 162 (30.8%) had peptic stenoses, 84 had stenoses of other etiologies (post-radiation, tuberculosis, mycotic, post-traumatic, collagenoses, skin diseases, etc.) (16.0%) patients. According to the classification of stenoses that we proposed in 1999 [5], 43 (8.2%) patients had stenosis of the first degree (9-11 mm), 126 (24.0%) had stenosis of the second degree (6-8 mm). III degree (3-5 mm) - 227 (43.1%), IV degree (0-2 mm) - 130 (24.7%) patients. Thus, in 67.8% of patients, the lumen of the esophagus in the narrowing zone did not exceed 5 mm (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Endophotography. a — critical burn stricture (IV degree) of the middle third of the esophagus (diameter 2 mm). Figure 1. Endophotography. b - pronounced peptic stricture (III degree) of the lower third of the esophagus (diameter 3-4 mm). Short strictures (up to 3 cm) were in 348 (66.2%), long strictures were in 178 (33.8%) patients, and in 82% of patients in this subgroup the length of the narrowing exceeded 5 cm. The upper edge of the stenosis was at the level of the pharynx and entrance to the esophagus in 62 (11.8%), in the upper third of the esophagus - in 113 (21.5%) patients. Double and multiple narrowings were diagnosed in 124 (23.6%) patients.

During the same period, endoscopic treatment was undertaken in 318 patients (197 men, 121 women) aged 16 to 88 years with cicatricial strictures of the esophageal anastomoses. Including in 237 (74.5%) patients, strictures developed after various types of esophagoplasty (mainly gastric tube and colon), in 38 (11.2%) - after gastrectomy, in 26 (8.2%) - after resection of the proximal stomach, 17 (5.3%) patients underwent other types of operations (for example, esophagoesophagostomy). According to the same classification, 59 (18.6) had grade I strictures, 83 (26.1) had grade II strictures, 124 (39.0) grade III strictures, 52 (16.0) grade IV strictures. 3%) of patients (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Endophotography. a - critical stricture of the esophageal-gastric anastomosis in the neck (IV degree) after esophagogastroplasty (diameter 1-2 mm), proliferation of granulations in the stump of the own esophagus above the anastomosis.

Figure 2. Endophotography. b - critical stricture of the esophagogastric anastomosis (IV degree) after resection of the proximal stomach (diameter 1-2 mm), suprastenotic dilatation and deformation of the esophagus.

In our experience, endoscopic treatment methods can be performed for any degree and extent of stenosis, however, the absolute indications for their use are: 1) grade III-IV esophageal stenosis (lumen no more than 5 mm);

2) high localization of the upper edge of the narrowing (pharynx, pharyngoesophageal junction, upper third of the esophagus); 3) large extent and tortuous course of the stricture; 4) eccentric location of the entrance to the stricture; 5) deformation of the suprastenotic part of the esophagus; 6) double and multiple narrowings; 7) strictures of esophageal anastomoses of any location and any degree of severity. Endoscopic bougienage is contraindicated if it is impossible to pass the guide string below the stenosis zone, since the frequency of perforations during blind bougienage or equivalent bougienage through a rigid esophagoscope varies from 10 to 17.6% [3, 16, 18], whereas with endoscopic bougienage along a string it is 0.1-2.5% [15, 17, 19-21, 23, 24], and with endoscopic balloon dilatation it ranges from 0 to 1.1% [1, 2, 21, 22, 25]. In this regard, we are convinced that blind bougienage should not be used.

Having been treating narrowing of the esophagus and esophageal anastomoses for a long time, at different stages we used various endoscopic methods: bougienage along a guide string (main and supporting courses), balloon hydrodilatation, dissection of the scar with high-frequency current, injections of lidase and corticosteroids into the scar area (in combinations with dilatation techniques), endoprosthetics with plastic tubular stents and, in one case, stenting with a self-expanding biodegradable stent. Bougienage along the guide string and balloon hydrodilatation turned out to be the most effective; we abandoned the other methods quite quickly.

The main methodological aspects of endoscopic bougienage of severe (3-5 mm) and critical (0-2 mm) stenoses of the esophagus and anastomoses, developed in our department, are as follows. The first and main stage is to pass a soft Metro or Fusion guide wire through the area of stenosis under the control of the upper edge of the narrowing (Fig. 3, a).

Figure 3. Endophotography.

a — passing a soft guide string through a critical burn stricture (IV degree) of the middle third of the esophagus under visual control of the upper edge of the narrowing. In exceptional situations, with a short narrowing with a straight stroke, if you have the appropriate experience, it is possible to initially use a rigid string with a spring tip (see Fig. 3, b).

Figure 3. Endophotography.

b — passing a rigid guide string through a critical burn stricture (IV degree) of the middle third of the esophagus under visual control of the upper edge of the narrowing. For critical stenoses with a diameter of less than 3 mm, the second stage is bougienage of the stenosis with Soehendra biliary bougies (Cook, USA) with a diameter of 5, 7, 8.5, 10, 11.5 Fr - from 1.5 to 4 mm (Fig. 4) .

Figure 4. Endophotography. Bougienage of a critical esophageal stricture with a Soehendra biliary bougie along a string. The third stage is passing a hollow bougie tube with a diameter of 3.5 mm and a length of 70-80 cm along a soft string. If the initial diameter of the narrowing allows (4-5 mm), then this tube can be passed without first expanding the stenosis with Soehendra dilators. The soft string is removed, and a hard Savary-Gilliard string with a spring tip is installed along the lumen of the hollow tube, since passing standard elastic Savary-Gilliard bougies along the soft string turns out to be difficult due to the lack of sufficient rigidity of the latter. The next, fourth stage is bougienage on a hard string with elastic bougies Savary-Gilliard (“Cook”, USA), starting with bougies No. 15 Fr to bougies No. 21-24 Fr (from 5 to 7-8 mm). For rigid stenoses, it is possible to use more rigid domestic bougies of the Savary type, starting from bougie No. 14 Fr. This expansion of the stenosis makes it possible to pass a small-caliber endoscope through it and perform the last stage - inspection of the intervention area in order to: 1) diagnose possible complications; 2) assessment of the zone of stenosis - length, position of the lower border, condition of the mucosa, the presence of a second narrowing, fistulas, possible signs of malignancy, etc.;

3) inspection of the underlying sections (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. a - Endophotography. Type of esophageal stricture after bougienage at different stages of treatment.

Figure 5. b - Endophotography. Type of esophageal stricture after bougienage at different stages of treatment.

Figure 5. c - Endophotography. Type of esophageal stricture after bougienage at different stages of treatment.

For endoscopic bougienage of esophageal stenoses and anastomoses with a diameter of more than 5 mm, the first step is to insert the endoscope into the stomach, graft or small intestine. This most often requires the use of small-caliber devices - pediatric gastroscopes or bronchoscopes. The second stage is to draw a rigid string 20-30 cm below the narrowing zone under visual control. Subsequent bougienage (third stage) is performed with standard Savary-Gilliard bougies, the diameter of which varies from 15 to 60 Fr (5-20 mm), and for rigid stenoses - with domestic Savary-type bougies, the maximum diameter of which is 13.3 mm (bougie No. 40 ).

Concluding the presentation of the methodological aspects of bougienage, we consider it important to note that exposure during bougienage is not required. No more than 3-4 bougies are performed in one session; for short strictures, bougies can be used one size at a time; for long strictures, bougies should be used in a row. Bougienage sessions are repeated every other day, the main course of treatment on average consists of 4-5 sessions. Bougienage of esophageal stenosis, as a rule, ends with bougies No. 42-45 Fr (14-15 mm), strictures of the esophageal anastomoses - with bougie No. 60 Fr (20 mm). Balloon hydrodilatation of esophageal strictures is currently, due to the design features of most modern balloon dilators, performed through the endoscope channel without a guide wire at a pressure of 2 to 6 atm, more often from 2 to 3 atm, which is controlled using a special syringe-pressure gauge. After reaching maximum pressure, an exposure of at least 2 minutes is required for adequate expansion of the stenotic zone.

To justify the choice between bougienage and balloon dilatation, we provide a comparative description of both techniques.

1. The use of Soehendra bougies with a diameter of 1.5 mm makes it possible to perform intervention for stenosis of any diameter, while for the introduction of a balloon dilator, a clearance in the narrowing zone of at least 3-4 mm is required.

2. The bougie is inserted only along the guide string, which ensures the safety of the intervention, and modern balloon dilators do not have a channel for the guide string and must be inserted blindly.

3. Bougienage can be performed for any length of narrowing. Balloon dilatation is effective only for short scar strictures.

4. Bougienage can be performed at any location of the narrowing, while for balloon dilatation it is preferable to localize the stricture 4-5 cm below the upper esophageal sphincter. For high strictures, balloons are not suitable (there is not enough space).

5. During one bougie, any number of narrowed zones can be dilated, whereas when using balloons for double or multiple narrowings, balloon dilatation of each of them must be performed sequentially.

6. When bougienage, the degree of rigidity of the stricture is determined by manual sensations, which allows you to control the applied force, limiting the forced overcoming of excessive resistance of scar tissue, and thus increases the safety of the intervention. With balloon dilatation, the force transmitted from the balloon to the tissues is not controlled, since the achievement of a given diameter of the balloon is carried out using a screw syringe, so the likelihood of a deep tear or rupture of the esophageal wall increases.

7. When bougiening dense strictures, they expand to the diameter of the bougie, which was successfully passed through the narrowing. Balloon dilatation is ineffective for rigid strictures - the “waist” is preserved while the balloon is filled to its maximum.

8. Bougienage does not require exposure, but balloon dilatation requires exposure for at least 2 minutes after reaching maximum balloon pressure.

9. Bougies are intended for repeated use; a high degree of disinfection is achieved with standard treatment with modern disinfectants. A special brush is used to treat the canal. Balloon dilators are disposable and quite expensive, and typically require at least 4-5 sessions to adequately dilate esophageal stenosis.

In connection with the above, we have now almost completely abandoned balloon dilatation in favor of endoscopic bougienage along a string. We use balloon dilatation only for pylorospasm and cicatricial strictures of colorectal anastomoses.

The most dangerous complications of endoscopic methods for dilating esophageal stenoses are perforation and bleeding. Perforation can be caused by the tip of the string when passing it blindly or by the end of the bougie when accidentally pulling the string above the stricture. In addition, a longitudinal rupture of the esophagus on the bougie may occur if excessive force is used and the rigidity of the stricture is underestimated. We have formulated the basic principles for preventing complications of endoscopic treatment of esophageal stenosis: 1) mandatory X-ray examination with a contrast agent before intervention; 2) preferential performance of interventions under local anesthesia; 3) selection of optimal timing for endoscopic interventions: burn strictures - no earlier than 2 weeks after the burn; strictures of esophageal anastomoses - no earlier than 10 days after surgery; 4) strict adherence to the technique of performing interventions;

5) it is advisable to use small-diameter endoscopes; 6) intervention should not be performed if it is not possible to pass the guide string;

7) the initial use of a rigid string is safe when passing the endoscope below the narrowing.

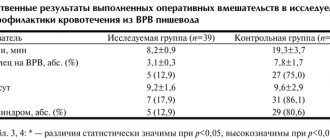

During endoscopic treatment of 526 patients with cicatricial strictures of the esophagus, the following immediate results were obtained. We were able to insert a guide wire and perform subsequent stages of endoscopic interventions in 514 (97.7%) of them. The remaining 12 patients were immediately operated on. In 366 (71.2%) patients, the only treatment method was bougienage, and the proportion of this intervention is constantly growing after the abandonment of balloon dilatation, which was used as the only technique in only 49 (9.5%) patients. In 99 (19.3%) patients, endoscopic treatment was combined. Complications occurred in

5 (1%) out of 514 patients: perforation - in 4 (0.8%), bleeding - in 1 (0.2%). All patients with esophageal perforation were operated on, and the bleeding was stopped using endoscopic methods. The immediate results were assessed as excellent (the achieved diameter in the area of stenosis was 14 mm or more) in 203 (39.5%) patients, as good (10-13 mm) in 108 (21.0%), in another 85 (16 .5%) observations, the results of endoscopic treatment were not assessed, since after the main stage, bougienage was continued under x-ray control. However, this is only possible for uncomplicated stenoses, therefore, if treatment in this subgroup were continued endoscopically, the final result would also be excellent or good. Consequently, in general, in 77% of patients the diameter in the area of stenosis after bougienage was more than 10 mm. In 65 (12.6%) patients, we assessed the results of endoscopic treatment as satisfactory - in them it was not possible to expand the lumen to more than 7-9 mm. The remaining 53 (10.4%) patients had unsatisfactory results. At the end of the main course of endoscopic treatment, 109 (21.2%) of 514 patients were operated on.

Of 318 patients with cicatricial strictures of esophageal anastomoses who underwent endoscopic treatment, it was possible to insert a string in 317 (99.7%), 1 patient was operated on. Of this number of patients, in 152 (48.0%) only bougienage was used to widen the narrowing, in 59 (18.6%) - balloon dilatation, and in 106 (33.4%) the treatment was combined. Such a high percentage of combined interventions in this group was due to the fact that we always strived to expand the esophageal anastomoses to at least 2 cm. In this regard, until 2004, when Savary-Gilliard bougies with a maximum diameter of 60 Fr appeared in our arsenal. 20 mm), any bougienage was completed in combination with balloon dilatation, since the maximum diameter of the domestic bougie No. 40 available at our disposal at that time was 13.3 mm, and that of the balloon dilator was 20-25 mm. Currently, as in the endoscopic treatment of esophageal stenosis, the proportion of combined interventions and balloon dilatation is decreasing in favor of bougienage as the only technique. In 95% of patients, excellent (final anastomosis diameter 15 mm or more) and good (10-14 mm) immediate results were obtained - 218 (68.8%) and 83 (26.2%) patients, respectively. In 7 (2.2%) patients, the results were assessed as satisfactory (anastomosis diameter up to 10 mm) and in the remaining 9 (2.8%) - as unsatisfactory. At the end of the main course of treatment, 12 (3.8%) of 317 patients were operated on.

In our experience, to prevent relapse of cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus (mostly short) and esophageal anastomoses, it is necessary to carry out long-term (from 1 to 2 years and from 3 to 6 months, respectively) planned maintenance treatment by bougienage with a gradually increasing interval for all patients, regardless of the immediate result primary endoscopic treatment. If the result of supportive endoscopic treatment is positive, dynamic observation is carried out in the future. Patients with esophageal strictures, if necessary, undergo bougienage 1-2 times a year, and if the stricture is prone to rapid restenosis, surgical treatment is indicated. After a full course of maintenance bougienage, re-treatment for strictures of the esophageal anastomoses is not required, since planned maintenance dilatations significantly improved the long-term results of endoscopic treatment of cicatricial strictures of the esophageal anastomoses: the relapse rate decreased from 25% (before 1994) to 3.0% by 2001 and up to 0 currently.

We believe that temporary endoprosthetics in this category of patients using tubular plastic stents should not be used. In the period from 1986 to 1994, 14 patients with esophageal stenosis and 8 patients with strictures of esophageal anastomoses underwent similar interventions to consolidate the achieved results and did not receive a single good or satisfactory result. Our own experience with the use of self-expanding biodegradable stents at the present time is negligible - one observation with a resistant stricture of esophagoenteroanastomosis, but its result was negative: rapid restenosis after resorption of the stent followed by surgical treatment. According to the experience of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery, stenting with self-expanding metal endoprostheses in patients with benign scar strictures of the esophagus and esophageal anastomoses for a long time is accompanied by severe complications. We observed 8 patients who underwent these interventions in other medical institutions. Indications for stenting were burn stricture of the esophagus (2), stenting periods were 13 and 16 months; esophageal-tracheal fistula (2), stenting period: 7 months; cicatricial stricture of the esophageal-small intestinal anastomosis of the II degree (1), stenting period 7 months; cicatricial stricture of the esophagogastric anastomosis after the Lewis operation, (1), double stenting was performed, stent installation periods were 13 and 5 months; failure of the esophageal-small intestinal anastomosis (1), stenting period 6 months; peptic stricture of the esophagus and stenosis of the postbulbar junction (1), double stenting was performed, the duration of the stents was 12 months.

The main complications that arose during long-term stenting for benign diseases of the esophagus and esophageal anastomoses: granulation at the edges of the stent, stricture above and/or below the stent, fistula between the gastric graft and the bronchus, detachment of the internal coating of the stent with partial overlap of its lumen, obstruction with food masses, fragmentation stent, ingrowth of the prosthesis into the wall of the esophagus (Fig. 6).

Figure 6. Endophotographs of complications of stenting with self-expanding stents for benign esophageal strictures and esophageal anastomoses. a — ingrowth of the stent into the wall of the esophagus, fragmentation of the stent.

Figure 6. Endophotographs of complications of stenting with self-expanding stents for benign esophageal strictures and esophageal anastomoses. b — cicatricial stricture of the esophagus above the stent; thread fixing the stent to the auricle.

Figure 6. Endophotographs of complications of stenting with self-expanding stents for benign esophageal strictures and esophageal anastomoses. c — bedsore and fistula between the gastric graft and the bronchus. It should be noted that only 2 out of 8 patients were able to undergo endoscopic interventions for complications of stenting. This is a long-term (over the course of a year) bougienage in 1 patient of an extended cicatricial stricture involving the lower third of the esophagus, esophagoenteroanastomosis and small intestine for 5 cm, and removal of a stent using endoscopic techniques in another patient. Subsequently, he underwent surgical separation of a large tracheoesophageal fistula, which only increased in size under the stent.

At the Russian Research Center of Surgery, 7 out of 8 patients were operated on for complications of stenting for benign diseases of the esophagus. The following very serious surgical interventions were performed: simultaneous extirpation of the esophagus with esophagoplasty with a gastric tube (1); simultaneous extirpation of the esophagus with esophagoplasty with a gastric tube, suturing of the tracheal defect (1); extirpation of the esophagus with two stents, suturing of tracheal defects, esophagostomy; delayed esophagoplasty with a gastric tube from the operated stomach (1), transthoracic extirpation of the esophagus and artificial esophagus (after Lewis operation) with two stents, esophagostomy, gastrostomy, delayed coloesophagoplasty (1); extirpation of the esophagus, esophagostomy, gastrostomy (first stage), duodenotomy, removal of the pyloroduodenal stent, gastroduodenostomy (second stage), coloesophagoplasty (1) and separation of the tracheoesophageal fistula (2) are planned. From this list it follows that the easiest operation was simultaneous extirpation of the esophagus with esophagoplasty with a gastric tube, if we do not take into account the separation of tracheoesophageal fistulas. Thus, the thoughtless use of a new technique - stenting with self-expanding stents, the lack of a clear treatment plan for the patient and dynamic observation with timely correction of complications that arise lead to disability of patients.

Thus, interventions using endoscopic techniques can be performed in most cases with benign cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus and esophageal anastomoses. According to our data, this was successful in 97.7 and 99.7% of patients, respectively. Our many years of experience indicate that for cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus, endoscopic treatment is futile if it is impossible to pass bougie No. 27 (9 mm) through the narrowing. In such situations, surgical intervention is indicated. For extended cicatricial stenoses of the esophagus, especially subtotal and total, endoscopic treatment in most cases should be a preparation step before planned surgical treatment. The frequency of relapses is high, the likelihood of developing severe complications, primarily perforation of the esophagus, increases with prolonged bougienage, and the possibility of converting an extended stricture into several short ones is exaggerated. In benign scar strictures of the esophagus and anastomoses, stenting with self-expanding metal endoprostheses can be performed if the narrowing is resistant to traditional dilatation methods for a short period of time, not exceeding, according to the literature, 4-6 weeks, with endoscopic monitoring every 2 weeks and timely removal of the stent. The feasibility of using self-absorbable (biodegradable) stents for long-term maintenance lumen dilatation in this category of patients requires further study.

Cicatricial stricture of the esophagus

Esophageal tube scars are most often formed as a result of the constant entry of gastric contents into the esophagus. This condition occurs with chronic reflux esophagitis against the background of a relaxed esophageal sphincter.

Another common cause of such a defect as cicatricial strictures of the esophagus is chemical burns. Accidental or deliberate ingestion of alkalis, acids, and other aggressive liquids during suicide forms deep necrosis, in which not only the entire thickness of the walls of the esophagus is affected, but often the pathology affects the surrounding tissues.

Therefore, scarring in the esophagus is undesirable.

Diagnostic methods

Suspicion of stenosis of the esophageal region in a patient arises based on the results of the anamnesis and clinic. If there is a defect such as cicatricial narrowing of the esophagus, it is determined using endoscopy and x-ray examination.

- Esophagoscopy - the doctor determines the diameter of the esophagus, the level of narrowing, examines the epithelium, takes a biopsy to determine the cause of the narrowing, and identifies defects in the form of ulcers, scars, tumors. Disadvantage of the examination: inability to examine the organ after the narrowed area.

- X-ray – done with a contrast agent, barium sulfate is used as contrast. Contrast allows you to see the lumen and relief of the organ, identify defects, and evaluate peristalsis. Using the method, differential diagnosis is carried out to exclude local protrusions of the esophageal walls or foreign bodies. These are the radiological signs of esophageal stricture.

Diagnostics

Esophageal stenosis suspected based on clinical symptoms is confirmed by endoscopic and x-ray examination. Using barium radiography of the esophagus, the passage of the contrast agent is traced, filling defects along the entire length of the esophagus are identified, its contours, peristalsis and relief are examined. Esophagoscopy allows you to determine the diameter and level of narrowing of the lumen, examine the mucous membrane, conduct an endoscopic biopsy to determine the cause of esophageal stenosis, and identify ulcerative, scar and tumor defects.

Why is the disease dangerous?

When stenosis develops against the background of reflux disease or for other reasons, the health and life of an adult or child arises. Difficulty swallowing or the inability to eat independently makes life worse and exhausts the patient. Timely diagnosis and proper treatment restore normal functioning and restore health. In most situations, only the surgical method allows the organ to return to proper functioning.

Gastrostomy

In case of complete anatomical stenosis, gastrostomy is mandatory. A special tube creates an artificial connection between the stomach and the external environment. This allows for enteral nutrition, which creates additional inconvenience for the person.

Symptoms

Symptoms of congenital esophageal stenosis occur during the first feedings of a newborn. They are manifested by profuse salivation, regurgitation of uncurdled milk, and mucus discharge from the nose. If congenital stenosis of the esophagus occurs in a moderate form, then the appearance of its symptoms coincides with the introduction of solid foods and the expansion of the child’s diet. The development of acquired stenoses occurs gradually. The main sign by which stenosis can be suspected is dysphagia (swallowing dysfunction).

Complications and consequences

The narrowing in the upper part is sometimes complicated by the entry of food or liquid into the respiratory passages. There is a risk of developing laryngospasm, which causes attacks of suffocation and severe coughing. Often the consequence of this condition is aspiration pneumonia .

If the stenotic condition persists for a long time, then an expanded lumen is formed above the narrowing site. In this case, the esophageal wall becomes thinner, as a result of which spontaneous rupture may occur. During endoscopy, the thinned area is often damaged by the endoscope, which also leads to rupture.

Large unchewed pieces of food can cause obstruction of the esophagus. Stuck food causes complete or partial obstruction of the esophageal tube. To remove stuck pieces, emergency esophagoscopy or surgery is required.

Treatment

Treatment of the disease can be either conservative or surgical. The treatment of narrowing of the esophagus in general is described in detail in this article. We also recommend reading about the two main surgical treatment methods - esophageal stenting, as well as bougienage of the esophageal tube.

Prevention and further prognosis

Effective preventive measures for esophageal narrowing involve treating the underlying disease. The prognosis of the general condition with modern methods of treatment is favorable. You should start treating GERD in the early stages, only in this way can you avoid relapses and be completely cured.

The esophageal region should be regularly monitored using contrast-enhanced X-rays to assess patency and detect early complications.

Such studies are necessary for patients who have undergone surgery on the esophagus or bougienage . X-ray examination is necessary one month after surgery, then after 3 months, and then 2 times a year.