1.What are esophageal varicose veins?

Varicose veins of the esophagus

- This is the dilation of blood vessels in the esophagus.

Sometimes the veins expand in the stomach. This disease does not cause any unpleasant symptoms if there is no rupture or bleeding from the vessels. , portal hypertension

can occur , a life-threatening condition.

Portal hypertension

- this is an increase in pressure in the portal vein system (the vein through which blood flows from the digestive organs to the liver), which is often associated with a blockage of all blood flow to the liver. Increased pressure in the portal vein leads to the development of large, swollen veins (varicose veins) in the esophagus, stomach, rectum and umbilical area. Varicose veins are fragile and rupture easily. And if a vein ruptures, large blood loss can occur. The most common cause of portal hypertension is cirrhosis of the liver. Cirrhosis is scarring of the liver as liver damage caused by hepatitis, alcohol, and other less common causes heals. In cirrhosis, scar tissue can block the flow of blood through the liver and slow its functioning.

A must read! Help with treatment and hospitalization!

results

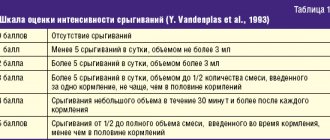

The immediate results of surgical interventions are given in table. 2.

Table 2. Immediate results of surgical interventions performed in the study groups during secondary prevention of bleeding from the esophageal esophagus Note. Here and in the table. 3, 4: * - differences are statistically significant at p<0.05, highly significant at p<0.01.

The average time of endoscopic operations performed using the modified method was 8.2±0.9 minutes, and using the standard method - 19.3±3.7 minutes, which turned out to be a statistically significant difference ( p

<0.05) and is explained by the number of ligatures applied to the esophageal esophagus: 3.1±0.3 rings on average in the study group and 7.8±1.7 rings in the control group (

p

<0.05).

4 hours after the operation, patients were allowed to drink only cold water, and from the 2nd day - to consume pureed or liquid food. Considering that on the 6-7th day necrotic ligatures come off and superficial ulcers appear in their place, which can serve as a source of bleeding, we consider it advisable to observe and treat patients in a hospital for 7-10 days. In this regard, the length of hospitalization of patients in the study and control groups was 9.2±1.6 and 9.6±2.9 days, respectively, which was a statistically insignificant difference ( p >

0,05).

All complications we identified occurred in the early postoperative period. No intraoperative complications were noted.

In the control group, 2 (5.5%) patients developed bleeding on the 1st day after surgery. In 1 case, bleeding was caused by a slippage of the ligature. Hemostasis was achieved with the installation of a Sengstaken-Blackmore probe and conservative measures. In another case, during an emergency endoscopy, a drip of blood was detected from under the base of the ligated node, and therefore endoscopic hemostasis was performed - paravasal sclerosis of this area with a 1% solution of ethoxysclerol, and conservative hemostatic therapy was carried out with a positive effect.

Other complications identified in 5 (12.8%) patients in the study group and 25 (69.4%) in the control group were associated with fever, a general reaction of the body to the presence of a foreign body in the esophagus (latex ring).

Thus, the differences in the frequency of complications identified in the early postoperative period turned out to be statistically highly significant ( p

<0.01). The modified technique of endoscopic ligation of esophageal varices we use reduced the incidence of their development by 5.8 times.

The differences in the incidence of dysphagia also turned out to be statistically highly significant - in 8 (17.9%) patients in the study group and in 31 (86.1%) in the control group ( p

<0.01), as well as in the development of severe pain syndrome - in 5 (12.8%) in the study group and in 29 (80.6%) in the control group (

p

<0.01). This difference is due to the fact that with the standard ligation technique used in the control group, a large number of latex ligatures were applied to the varicose nodes of the upper third of the esophagus, thereby causing discomfort when swallowing, as well as chest pain, reducing postoperative indicators of the quality of life of patients, most often during the first 3 days. The modified endoscopic ligation technique we used made it possible to reduce the incidence of dysphagia by 4.8 times and severe pain syndrome by 6.2 times.

To assess the long-term results of the operation, as well as to resolve the issue of re-ligation, all patients underwent a control endoscopy and a comprehensive examination 1 month after the operation (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of surgical interventions performed in the study groups 1 month after the operation

It is important that all our patients were under the dynamic supervision of a surgeon and hepatologist, following the recommendations given to them. Patients were prescribed drugs from the β-blocker group under pulse control within the range of 60–66 beats/min; antisecretory therapy was mandatory; additionally, hepatoprotective and antianemic therapy was carried out. 1 month after discharge from the hospital, patients underwent laboratory and instrumental examination.

Differences in the average severity of esophageal varices 1 month after surgery in the study (1.18±0.36) and control (1.23±0.37) groups turned out to be statistically insignificant ( p

>0.05) (see Fig. 3, 4).

Rice. 3. EGDS control 1 month after ligation of the esophageal varices using a modified technique (upper and middle third of the esophagus).

Rice.

4. EGD control 1 month after ligation of the esophageal varices using a modified technique (lower third of the esophagus and esophagocardial junction). During control endoscopy 1 month after surgery, 3 (7.7%) patients in the study group and 15 (41.7%) in the control group were diagnosed with type I gastric varices ( p

<0.01). We explain the differences by the fact that the imposition of a larger number of ligatures in the control group on the venous trunks in the esophagus, in particular throughout its entire length, caused an almost complete closure of the venous blood supply, which prevents adequate outflow of blood from the veins of the stomach into the veins of the middle and upper third of the esophagus. As a result, there was greater blood flow to the stomach with the formation of gastric vasculature. Thus, the modified ligation technique we used reduced the incidence of gastric varices by 5.4 times.

We believe that by using a modified technique of applying latex ligatures in the area of the lower and distal segment of the middle third of the esophagus, we maintain partial collateral outflow of blood from the veins of the stomach to the veins of the upper and middle third of the esophagus, thereby reducing the risk of formation of gastric varices. Considering that in the upper and middle third of the esophagus the thickness and elasticity of the venous wall is greater than in its lower third, the risk of esophageal varices of the esophagus is much lower, and the risk of bleeding from them is minimal.

In addition, one of the important key points in preventing the formation of new VVs of the esophagus and stomach is adequate treatment in the postoperative period, which should be aimed primarily at reducing pressure in the portal vein.

In connection with the diagnosis of grade III esophageal varices, 1 month after ligation, a repeat session of endoscopic esophageal varices ligation was performed in 2 (5.1%) patients in the study group and 2 (5.6%) in the control group.

Cicatricial stenosis of the esophagus, complicated by grade III dysphagia, was observed in 2 (5.6%) patients in the control group. These patients underwent 3 sessions of endoscopic bougienage of the esophagus with a positive effect.

If after 1 month there was no need for re-ligation, control EGD was performed in patients after 6 months (Table 4).

Table 4. Results of surgical interventions performed in the study groups 6 months after surgery

Differences in the severity of esophageal varices 6 months after endoscopic ligation were not statistically significant ( p

>0.05).

The severity of esophageal varices was on average 1.46±0.53 and 1.48±0.61 in the study and control groups, respectively. The need for repeated surgery during this observation period occurred in 2 (5.1%) patients in the study group and in 4 (11.1%) in the control group, which was also not statistically significant ( p

>0.05).

In 1 (2.6%) patient in the study group and in 4 (11.1%) in the control group, a control endoscopy 6 months after surgery revealed a primary formation of type I gastric varices ( p

>0.05).

Thus, after 6 months of observation, gastric varices were diagnosed in 12 (30.8%) patients in the study group and in 29 (80.5%) in the control group ( p

<0.01).

2.What are the symptoms of bleeding from varicose veins?

As we have already said, varicose veins of the esophagus themselves do not cause any discomfort. But if a vein ruptures and starts bleeding, it is dangerous and requires emergency medical attention. Symptoms of varicose veins of the esophagus or stomach and the onset of bleeding from them may include:

- Vomiting blood;

- Black or bloody stools;

- Low blood pressure;

- Increased heart rate;

- Shock (in particularly serious cases).

Visit our Gastroenterology page

Types of gastrointestinal bleeding

The content of the article

The severity of bleeding can range from microscopic blood loss to massive bleeding with the release of large amounts of blood (usually a mixture of blood, clots, and possibly hematin) through the mouth or anus, which can lead to hypovolemic shock and death.

Microscopic blood loss can only be detected in stool using specialized laboratory tests. The condition can also be identified by the results of peripheral blood tests and decreased iron levels.

Gastrointestinal bleeding is divided into:

- Bleeding from the upper gastrointestinal tract

. Their source is between the pharynx and the ligament of Treitz (duodenal ligament). They are involved in 80% of cases of gastrointestinal bleeding; - Gastrointestinal bleeding from the lower gastrointestinal tract

. Their source is between the ligament of Treitz and the rectum; - Hidden gastrointestinal bleeding

. This form differs from ordinary bleeding in its clinical picture and requires specific diagnostic procedures.

3. Treatment of the disease

Bleeding from varicose veins is an emergency condition that requires immediate medical attention. If the bleeding is not controlled, the person may even die. In severe situations, the patient may require mechanical ventilation to prevent the lungs from filling with blood. In addition to stopping bleeding, treatment for varicose veins of the esophagus or stomach is aimed at preventing recurrent bleeding. Here are the procedures that can be used for these purposes:

- Bandaging.

During this procedure, the gastroenterologist places small rubber bands directly over the varicose veins. This stops bleeding and allows you to cope with varicose veins. - Sclerotherapy.

During sclerotherapy, the doctor injects a blood clotting drug directly into the area of varicose veins. - Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt

(TIPS) is a radiological procedure in which a stent (tubular device) is placed in the liver. A stent connects the hepatic vein to the portal vein. This procedure is performed by inserting a catheter through a vein in the neck. The purpose of intrahepatic bypass is to reduce high pressure in the liver. - A distal splenorenal bypass

is a surgical procedure that connects the splenic vein and the vein of the left kidney to relieve pressure in the varices and stop bleeding. - Liver transplantation

is a last resort measure that can be used in cases of end-stage liver disease and in conditions that seriously threaten the life and health of the patient. - Devascularization

is a surgical procedure that removes bleeding varicose veins. Devascularization is performed when bypass surgery is not possible or other measures do not help control bleeding from esophageal or gastric varices.

About our clinic Chistye Prudy metro station Medintercom page!

Immunochemical tests

Immunochemical tests

Immunochemical tests (HemeSelect, FECA, I-FOBT and Hemoccult ICT), used within European standards, detect undenatured human hemoglobin and give a positive result when it enters the gastrointestinal tract in an amount of 0.3 ml/24 hours.

These tests are not positive if the source of the bleeding is found in the upper gastrointestinal tract—hemoglobin from this source is denatured and degraded before it reaches the stool.

Determining the cause of bleeding - endoscopic and radiological methods

A history and physical examination are performed by a gastroenterologist in accordance with the principles of treatment when analyzing bleeding from the upper or lower gastrointestinal tract.

Further tests for a patient who tests positive for blood in the stool include:

- Peripheral blood test - looking for signs of anemia;

- Endoscopic examinations of the gastrointestinal tract - esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy. These tests help identify the possible source of bleeding. Colonoscopy may be considered sufficient in the absence of anemia or gastrointestinal symptoms.

Enteroscopy offers great diagnostic and therapeutic options in case of suspicious changes in the small intestine.

When endoscopic examinations do not help determine the source of bleeding, X-ray examination

small intestine with evaluation of the fragment and possibly enteroclysis.

In difficult cases, CT or MRI enterography and endoscopic examination are performed using a special capsule with a built-in video camera, which the patient swallows like a regular pill.

Treatment of internal bleeding

Treatment of internal bleeding is carried out in a hospital; the choice of department depends on the source of internal blood loss: it can be the department of general surgery, gynecology, neurosurgery, and so on.

In this case, specialists solve three problems:

- stopping internal bleeding;

- compensation for blood loss;

- improvement of microcirculation.

In some cases, in order to stop the bleeding, it is enough to cauterize the bleeding area, but most often surgical intervention under anesthesia is necessary. The specific actions of the surgeon, again, depend on the type of internal bleeding.

This article is posted for educational purposes only and does not constitute scientific material or professional medical advice.