Lymphofollicular hyperplasia (LFH) is a malignant or benign proliferation of lymphoid tissue of the mucous membrane. In most cases, lymphoid hyperplasia is caused by benign diseases. Pathology can be detected in the organs of the endocrine system, but is more often found in the digestive tract (stomach, duodenum and ileum). The diagnosis is confirmed by histological examination of the removed lymphoid tissue. Symptoms can vary significantly depending on the underlying disease.

In the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), benign neoplasms of the digestive organs are designated by the code, and neoplasms of the stomach by D13.1.

What is lymphofollicular hyperplasia?

Generalized signs of lymphofollicular hyperplasia are considered to be an increase in temperature, a feeling of weakness, a quantitative increase in lymphocytes

Lymphoid hyperplasia of the gastrointestinal tract is divided into local (local) and diffuse (scattered). With local lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon, visible polyps are formed. Diffuse lymphoid hyperplasia is a scattered benign neoplasm; it is thought to be a general response of mucosal lymphoid cells to an unknown stimulus.

Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia of the duodenal bulb is characterized by multiple individual mucous nodules. The most common cause of malignant lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the intestine or stomach is extranodal B-cell lymphoma from marginal zone cells (maltoma, or MALT lymphoma).

Some studies show that maltoma is slightly more common in women than in men. No significant racial differences in disease prevalence were identified; Some studies suggest that lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the ileum is slightly more common in white people than in black people.

Symptoms

Symptoms of LFH vary greatly and depend on the underlying cause. In some cases, they can also be similar to the symptoms of stomach cancer. However, some patients are more likely to suffer from heartburn, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and flatulence.

Prolonged vomiting and nausea are signs of late stage maltoma. If you suddenly lose your appetite, experience unexplained diarrhea or stomach discomfort, it is recommended to consult a doctor. Maltomas in the early stages can be cured. Later stages of the disease are difficult to treat.

Initially, patients feel weak, suffer from loss of appetite, and sometimes nausea. Sometimes there is a diffuse feeling of pressure in the abdomen. Only at the last stage, in addition to night sweats, abdominal pain and fever occur. Sometimes body weight decreases.

With LFG of the intestine, intestinal bleeding is possible.

Causes

Concomitant problems - obesity, liver dysfunction - can trigger the pathogenic mechanism of lymphofollicular hyperplasia

During infections or inflammations in the body, the work of the immune system is enhanced: the division of immune cells - lymphocytes - accelerates in the lymph nodes. The main function of lymph nodes is to filter lymph. To ensure immune functions, the lymph nodes become significantly enlarged - this is a normal and healthy sign of increased immune activity.

The lymph node may also become enlarged due to the growth of malignant cells. As a rule, lymph nodes affected by cancer do not cause pain when touched and are difficult to move because they merge with the surrounding tissue.

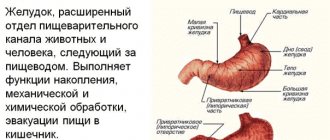

There are numerous lymph nodes in the wall of the stomach. If they are malignantly enlarged, they are called gastric lymphoma. Most gastric lymphomas are malignant maltomas that are limited to the gastric mucosa. MALT stands for mucosa-associated lymphatic tissue.

There are primary and secondary gastric lymphomas. Primary make up about 80% of all lymphomas of the digestive tract. They develop directly from lymphoid cells of the gastric mucosa. There are no other diseases that would contribute to the development of the disease. Secondary gastric lymphomas develop as a result of metastasis of tumors located in other organs.

The ileum constitutes approximately 60% of the entire length of the small intestine and is thus up to 3 m in adults. The ileum contains a large number of lymphoid follicles called Peyer's patches. Lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the ileum occurs due to primary or secondary immunodeficiency, as well as chronic inflammatory bowel disease - Crohn's disease.

Lymphoid hyperplasia of the colon often occurs in combination with polyposis. Lymphofollicular intestinal hyperplasia is common in newborns and children under 6 years of age. The exact cause of lymphoid hyperplasia has not been established. It is believed that lymphoid hyperplasia may be a response to various irritants (medicines, food components).

Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH)

Nodular lymphoid hyperplasia (NLH) is a rather rare benign disease characterized by multiple nodules in the mucous membrane of various parts of the gastrointestinal tube: the small and large intestines, as well as the stomach.

The prevalence of this disease is not fully known; it is quite common in children under 10 years of age, but can sometimes be observed in adults.

Classification of NLH

There are two forms of the disease:

1) Focal NLH - represented by individual foci, most often localized in the terminal ileum, rectum and other parts of the gastrointestinal tract

2) Diffuse NLG - this form is characterized by the involvement of large sections of the gastrointestinal tube (for example, the entire small intestine).

Etiopathogenesis of NLH

The pathogenetic mechanisms of the development of NLH still remain unclear. However, there are several theories that differ from each other depending on whether the patient has an associated immunodeficiency condition or not.

So, if the patient has confirmed immunodeficiency, then the formation of nodules in the mucous membrane may be the result of the accumulation of plasma cell precursors (incapable of fully maturing B-lymphocytes).

NLH in the absence of immunodeficiency disorders may be associated with immune stimulation of intestinal lymphoid tissue. This hypothesis assumes the presence of constant irritants (triggers) in the lumen of the gastrointestinal tube, most often of infectious origin. Repeated stimulation of immune cells can lead to eventual hyperplasia of lymphoid follicles. Such a mechanism may explain the frequent association of giardiasis and Helicobacter pylori with NPH (see below).

Clinical manifestations of NLH

Often, LPH has no symptoms and is an incidental finding during endoscopic examination of the stomach, colon and small intestine. However, some researchers have associated LPH with gastrointestinal symptoms such as chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, gastrointestinal bleeding (occult or obvious, from the rectum), and intestinal obstruction (very rare). Some patients may experience protein loss and weight loss.

The extent to which NLH contributes to symptoms is still unclear. Is this condition the root cause of the complaints or is LPH just an incidental finding in a patient with gastrointestinal symptoms? There are more questions than answers.

Diseases and conditions associated with NLH

Quite often compared to other individuals, NLH is detected in patients with immunodeficiencies. Thus, 20% of patients suffering from common variable immunodeficiency (CVID) have LPH. CVID is a disease characterized by a decrease in the levels of immunoglobulins of various subclasses (G, A, M), an impaired immune response due to a decrease in the production of antibodies. Patients often suffer from recurrent bacterial respiratory tract infections, autoimmune diseases and have an increased risk of developing cancer pathologies. NLH in CVID is usually generalized, involving the entire small intestine.

NLH is often associated with selective IgA deficiency, which is detected in 1 in 300-700 Caucasians. In such people, there is a decrease in the level of IgA in the blood below 0.7 g/l with normal or even elevated levels of other immunoglobulins. Most people with selective IgA deficiency are asymptomatic, but some of them have recurrent upper respiratory tract infections, autoimmune diseases, allergies and gastrointestinal pathologies (celiac disease, NPH).

NLH can be associated with giardiasis in both individuals with a normal immune response and those with immunodeficiency. The triad of HLH + giardiasis + decreased levels of gamma globulins is known as Herman's syndrome.

Helicobacter pylori infection can cause the development of LPH involving the stomach and duodenum.

LPH is also common in people with HIV infection and may be associated with familial adenomatosis of the colon and Gardner's syndrome.

There is evidence of a possible association of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) with HLH. At the same time, a number of authors consider NLH as a manifestation of low-active inflammation in the mucous membrane of the colon in patients with IBS.

Complications of NLH

NLH is a benign disease and extremely rarely leads to the development of complications. However, cases of intestinal obstruction in persons with a widespread process in the small intestine, as well as intestinal bleeding, have been described.

People with LPH are known to have an increased risk of lymphoproliferative diseases (lymphoma), but the exact risk is not known.

Diagnosis of NLH

There are two main methods for diagnosing NLH:

1) Endoscopic - detection of nodules of various sizes (2-10 mm, average 5 mm) on the mucous membrane of the stomach, small intestine, colon/rectum. Such nodules (most often in the form of raised papules) can be detected during gastroscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, enteroscopy or capsule endoscopy.

In the photo - NLH in the duodenum.

2) Histological method - detection in the mucous membrane and in the superficial part of the submucosal layer of enlarged (hyperplastic) lymphoid follicles, which usually form groups and can practically merge with each other.

Differential diagnosis

Differential diagnosis of LNG is carried out with lymphoproliferative diseases (lymphoma of the small intestine, stomach). When NLH is localized in the colon, its elements (nodules) may resemble adenomatous polyps.

It is important to remember that in some patients, lymphoid follicles may also be detected in the ileum during ileocolonoscopy. In this zone, the concentration of lymphoid follicles is maximum compared to other parts of the intestinal tube. Moreover, unlike NLG, the nodules (the same lymphoid follicles) are small in size (1-3 mm, rarely larger), they are located separately from each other, without merging, and areas of normal mucosa are visible between them. These changes should not be considered a pathology, they are a variant of the norm.

Treatment of NLH

LNG itself does not require treatment. If there are associated diseases (giardiasis, Helicobacter pylori infection), therapy should be carried out aimed at removing the pathogen.

NLG forecast

The prognosis of NLH is generally favorable; in most cases, only dynamic monitoring of the patient is required.

Diagnostics

Examinations allow us to determine the level of spread of neoplasms, and endoscopy allows us to obtain the necessary sample of tissue for a biopsy in order to obtain information about the presence or absence of histology

First, a physical examination of the patient is performed and a history is taken. Imaging techniques (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography) do not accurately visualize LPH but may be helpful in confirming the diagnosis.

Gastroendoscopy can reveal local changes in the gastric mucosa.

Colonoscopy and sigmoidoscopy are used to identify lymphofollicular intestinal hyperplasia.

Signs of bone marrow damage can be identified by histological examination. Histologically, lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the gastric mucosa is characterized by a large number of immunocompetent cells in the lamellar layer of the mucous layer.

Cytogenetic studies can reveal chromosomal abnormalities in malignant cells. The most common anomalies are trisomy 3, t(11;18) and, less commonly, t(1;4).

Reasons for the formation of polyps

The causes of the formation of polyps in the duodenum can be:

- inflammation of the duodenal mucosa,

- increased acidity of gastric juice,

- pathology of the gallbladder and biliary tract, pancreas,

- infection in the upper gastrointestinal tract - helicobacteriosis of the stomach and duodenum, giardiasis of the duodenum, etc.,

- disorders of the intestinal microflora (microbiome), habitual constipation,

- chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract,

- low physical activity, overweight,

- excess diet of fatty, fried, salty, and smoked foods,

- taking medications (for example, anti-inflammatory non-steroidal drugs, etc.)

Classification

In medicine, benign and malignant forms of LFG are distinguished.

Less than 45% of lymphofollicular hyperplasias of the stomach are benign. In most cases, they are the result of past, long-term infection of the gastric mucosa by Helicobacter pylori.

Determination of the stage of maltoma is carried out in accordance with the Ann Arbor classification adapted by the International Study Group of Extranodal Lymphomas. There are 4 main stages of maltoma development. At stages I and II, involvement of distant and nearby lymph nodes is observed. Stages III and IV are characterized by involvement of neighboring organs and tissues, as well as lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm.

Treatment

You should not try to cure the disease on your own; if you detect the first signals of an impending disease, you should consult a gastroenterologist for advice

Benign lymphofollicular hyperplasia does not require treatment.

If a malignant growth of gastric lymphoid tissue is diagnosed at an early stage, antibiotic therapy can help eliminate Helicobacter pylori.

Most lymphofollicular hyperplasia of the gastric antrum respond to modern treatment methods - radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

In later stages, surgery may help by removing only the affected part or the entire stomach. Complete removal of the stomach is called a gastrectomy.

Tumors that are limited to the inner layer of the stomach wall (mucosa) can be removed during gastroscopy. In this case, only part of the tumor and immediately adjacent tissue are removed. For deep-seated tumors, part or all of the stomach, including surrounding lymph nodes, the spleen, and part of the pancreas, must be removed. To restore the passage of food, the rest of the stomach, or the end of the esophagus, is connected to the small intestine.

Additional chemotherapy (given both before and after surgery) may improve the chances of survival for patients with locally advanced tumors that have an increased risk of recurrence.

If the tumor has spread to the abdomen (peritoneal carcinomatosis), the patient's life can be prolonged by surgical removal of the affected peritoneal membrane in combination with so-called hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy.

If the tumor cannot be completely removed, surgery is not performed. In this case, drug treatment (chemotherapy, possibly in combination with other medications) can relieve symptoms, prolong and improve quality of life.

If the stomach is severely compressed by a tumor, inserting a plastic or metal tube (called a stent) may help you eat normally.

Many patients suffer from digestive problems after surgery.

What is a polyp

This problem worries many people who have polyps in different parts of the gastrointestinal tract. In the medical practice of a gastroenterologist, the most common polyps are stomach and colon , less commonly the esophagus duodenal polyps .

Polyp is any formation on the mucous membrane of the duodenum, protruding into the intestinal lumen and connected to the wall by a stalk or “stem” extending from the surface of the intestinal wall, or by a wide base. The body of the polyp is formed by epithelial particles and has multiple blood vessels.

Polyps form on the constantly inflamed mucous membrane of the duodenum, which causes impaired recovery (regeneration) of the mucous membrane and the formation of “excess” tissue (polyp). Polyps are classified as inflammatory (hyperplastic), they grow from the normal intestinal mucosa and never become malignant. Hyperplastic (inflammatory) polyps can disappear - the inflammation goes away - the polyp goes away. The minimum sizes of polyps are from 5 to 20 mm, large ones are more than 20 mm.

Polyps by their nature are benign tumors - safe conditions, but in 25% there is a risk of malignant degeneration of “true” polyps. The nature of the polyp is clarified by taking a biopsy.

In the duodenum, benign tumors developing from smooth muscle tissue are more often observed, very rarely lipomas from adipose tissue, fibromas from connective tissue, lymphangiomas from lymphatic tissue, hemangiomas from blood vessels.

Most often, single polyps of the duodenum are observed, but there may be several polyps, and then we can talk about “polyposis” of the duodenum. Polyps of the duodenum grow slowly and are small in size in the early stages of development.

Polyps of the duodenum are a rare occurrence nowadays, but occur at any age.

Forecast

The prognosis depends on the grade of the tumor; The 5-year survival rate for patients with early-stage indolent maltoma is 50%. In later stages, the prognosis is poor; The five-year survival rate is 25%.

Early treatment can significantly prolong the life of patients with lymphofollicular hyperplasia.

Patients are prohibited from self-medicating, since improper therapy can aggravate the disease. Traditional methods are allowed to be used only after consultation with a doctor, since some remedies can cause serious side effects and interact with chemotherapy drugs.