Authors: Marco Di Serafino, Valerio Vitale, Rosa Severino, Luigi Barbuto, Norberto Vezzali, Federica Ferro, Eugenio Rossi, Maria Grazia Caprio, Valeria Raia, Gianfranco Vallone

Anatomy, technique and sonographic aspects

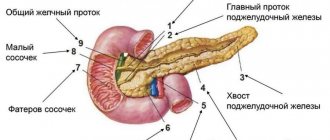

The pancreas is located in the anterior pararenal space, in the retroperitoneal space, and is directed obliquely, and its head part is located on the right, at a level below the tail. The head is enclosed in the duodenal cavity, and the tail is between the stomach and spleen. The superior celiac vessels, along with the superior mesenteric vessels and the splenic vein axis, represent an important anatomical landmark for the pancreas (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 : Schematic representation of the anatomical landmarks of the pancreas: it is located in the retroperitoneum, anterior to the major abdominal vessels and the lumbar spine. The splenic vein is an important anatomical landmark (asterisk). The pancreas is divided into a head (1) on the right, a body (2) in the middle, and a tail (3) on the left.

On ultrasound, the glands are better visualized in children than in adults due to their smaller size and the relatively large left lobe of the liver, which serves as an acoustic window, and is also easily recognized due to several important anatomical landmarks such as the aorta, inferior vena cava, splenic vein and mesenteric vessels.

Examination of the pancreas usually begins with a transverse scan, followed by a longitudinal and oblique scan using the left lobe of the liver as an acoustic window for the head and body (Figure 2), the spleen for the tail (Figure 3), and finally the stomach window. filled with water to visualize the body of the isthmus (Fig. 4).

Figure 2 : Longitudinal ultrasound scan of the epigastrium from medial to lateral direction. The head and body of the pancreas (asterisk) are identified through the acoustic window of the left lobe of the liver (arrow).

Figure 3 : Longitudinal (a) and transverse (b) ultrasound of the left hypochondrium. The tail of the pancreas is identified through the acoustic window of the spleen.

Figure 4 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound. The body of the isthmus of the pancreas (asterisk) is clearly visible if the intestinal window is dilated with water. From left to right, progressive filling of the stomach.

The overall ratio of gland size to patient body size decreases with age. Typically, in children, the head of the pancreas is relatively more pronounced than the body and tail, and this should not be mistaken for pathological processes.

The pancreas grows primarily during the first year of life, growing more slowly between the 2nd and 18th years, increasing its anteroposterior diameter (a–p diameter) over time (Figure 5 and Table 1).

Figure 5 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. To assess the diameter of the pancreas, measure the anteroposterior diameter of the pancreas (calipers). Head (a), body (b) and tail (c) of the atrophied pancreas.

Table 1.

| Age | Head | Body | Tail |

| Newborns | 0.5–1.0 | 0.5–1.1 | 0.5–0.8 |

| 0-6 | 1.0–1.9 | 0.4–1.0 | 0.8–1.6 |

| 7-12 | 1.7–2.0 | 0.6–1.0 | 1.3–1.6 |

| 13-18 | 1.8–2.2 | 0.7–1.2 | 0.3–1.9 |

Typically, the ecostructure of the pancreas is isoechoic or slightly more echogenic compared to the liver because the parenchyma is replaced by fibrosis and fat, but is less pronounced due to its glandular structure, which causes several interfaces (Fig. 6); The Wirsung duct is also identified by ultrasound as a tubular anechoic structure (Fig. 7). The average diameter of the pancreatic duct in healthy children is 1.65 ± 0.45 mm.

Figure 6 : Oblique ultrasound of the pancreas in the epigastrium with the patient in the right lateral position. The pancreas is oriented horizontally and is characterized by a homogeneous echostructure, which can appear either hypoechoic (a) or hyperechoic (b).

Figure 7 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. The pancreas, which appears isohypoechoic, has a thin anechoic tubular structure representing Wirsung's canal (arrowheads).

Signs of severe pathology

Despite the variety of clinical manifestations of pathologies in which the pancreas can enlarge, some symptoms may indicate the presence of a pathological process in the organ. Particular attention should be paid to the following phenomena:

- bitter taste in the mouth, belching;

- loss of appetite up to its complete absence, nausea and vomiting after eating;

- diarrhea or constipation;

- pain in the upper abdomen or under the ribs. Often the pain radiates to the back or left arm, sometimes it can be burning.

If the symptoms listed above are accompanied by elevated body temperature, inflammation of the gland should be suspected - pancreatitis. Usually in such cases the clinical picture appears quickly and gradually intensifies. This is often accompanied by a significant deterioration in general condition.

Inflammation of the pancreas is often accompanied by fever

If a child has an enlarged tail of the pancreas, manifestations of the disease will not appear immediately. You may experience a slight burning sensation in the upper abdomen, decreased appetite, or nausea. If your baby experiences regular occurrence of such symptoms, you should consult a doctor as soon as possible.

Timely diagnosis is very important to prevent complications of the disease. This is due to the fact that the pancreas is located close to other organs of the digestive system. Therefore, with an enlarged head, intestinal obstruction may occur.

Anatomical options

Anatomical abnormalities of the pancreas are classified as fusion abnormalities (pancreas divisum), migration of an abnormal ring-shaped pancreas (ectopic pancreas), or duplication abnormality (change in number or shape).

Division of the pancreas occurs as a result of disruption of the fusion of the ventral and dorsal primordia. The ventral (Wirsung) duct drains only the ventral bud of the pancreas, while most of the gland drains into the minor papilla through the dorsal (Santorini) duct.

The incidence is estimated to range from approximately 5 to 10% of the population. It is not often identified by sonography, although it can be easily recognized when the ducts are ectatic and also during pancreatitis (Fig. 8).

Figure 8 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Pancreas divisum: the dorsal pancreatic duct (arrow) is in direct connection with the duct of Santorini; The ventral canal of Wirsung (arrowhead) opens into the intestinal lumen. Note the enlarged head of the pancreas (dotted double-headed arrow) in acute pancreatitis.

Annular pancreas is a rare congenital anomaly characterized by pancreatic tissue that completely or partially covers the descending duodenum. The prevalence is approximately 1 in 2000 people. It is often associated with other congenital anomalies such as esophageal atresia, imperforate anus, congenital heart defects, midgut malrotation, and Down syndrome.

Two types have been proposed: an extramural subtype, where the ventral pancreatic duct surrounds the duodenum to join the main pancreatic duct, and an intramural subtype, where pancreatic tissue mixes with muscle fibers of the duodenal wall and numerous small ducts empty directly into the duodenum. . It can have a wide range of clinical severity and can affect neonates and the elderly, making diagnosis difficult.

About half of patients with neonatal duodenal obstruction may have a “double bubble” on abdominal x-ray if the obstruction is complete. This condition is difficult to confirm by ultrasound, but the rounded head of the pancreas and the proximal part of the duodenum passing through the head should raise suspicion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) easily confirms the diagnosis; the latter imaging modality is preferred for assessing both the pancreas and ducts (Fig. 9).

Figure 9 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Annular pancreas: head of the pancreas surrounding the duodenum with normal peristalsis (top line a–c). The annular pancreas is clearly visible on MRI (bottom line).

Treatment of chronic pancreatitis in children

Edema of the pancreas in acute pancreatitis (computed tomogram)

According to modern concepts, CP is an inflammatory-degenerative process in the pancreas, the final stage of which is fibrosis of the parenchyma with a gradual decrease in exocrine and endocrine functions.

Etiology

| The use of octreotide for chronic pancreatitis makes it possible to quickly relieve pain and reduce enzymatic activity |

Among the many etiological factors of pancreatitis in children, the leading role is played by pathology of the duodenum

(41.8%),

biliary tract

(41.3%),

as well as

abnormal development of the gland and abdominal trauma. Other causes of CP can be

infections

(mumps, hepatitis viruses, enteroviruses, salmonellosis, etc.), helminthiasis and other diseases, in particular connective tissue diseases, hyperlipidemia, usually type I and V, hypercalcemia, chronic renal failure.

The toxic effect of some drugs

(corticosteroids, sulfonamides, cytostatics, furosemide, etc.) on acinar tissue is known.

A special place among the causes is occupied by hereditary pancreatitis, cystic fibrosis, Shwachman's syndrome, isolated deficiency of pancreatic enzymes and other hereditary diseases

occurring with pancreatic insufficiency.

According to our data, CP in children in most cases develops secondarily, and as a primary disease it occurs only in 14% of patients

[1,4].

Pathogenesis

| The use of antiproteases in pediatrics is advisable in the initial stages of pancreatitis, since by suppressing trypsin and kinin activity, they prevent the formation of systemic complications |

As is known, the main pathogenetic mechanisms for the development of most forms of CP are intraductal hypertension

and activation of pancreatic enzymes (

autolysis

), which leads to edema, necrosis and subsequently, when the process recurs, to sclerosis of the parenchyma. Therefore, when choosing a treatment program for CP, it is necessary to take into account the features of clinical and morphological variants: interstitial-edematous, parenchymal, fibrous-sclerotic, cystic [5, 6].

Treatment

View

[ ]

CP in children requires an individual therapeutic approach.

During the period of exacerbation, the child's stay in the hospital, the creation of physiological rest and sparing of the diseased organ are indicated, which ensures the prescription of sedatives and bed rest. Diet therapy

View

[]

An important place in the complex of conservative measures belongs to therapeutic nutrition, the main goal

of which is

to reduce pancreatic secretion

. The high sensitivity of patients with pancreatitis to the qualitative and quantitative composition of food is well known. With the help of a diet, pancreatic secretion is reduced, the absorption of food ingredients is facilitated and the energy and plastic needs of the body are compensated.

When drawing up a pancreatic diet (table No. 5p), it is necessary to take into account the patient’s age, physical status, period of illness, features of metabolic processes, the presence of concomitant gastroenterological pathology, diet, and method of cooking. Diet in the acute phase

Pancreatitis is characterized by physiological protein content, moderate limitation of fats, carbohydrates and the most complete exclusion of extractives and juice products (raw vegetables, fruits, juices).

In the first days

of severe exacerbation, it is recommended to abstain from eating. Rose hip decoction, unsweetened tea, and alkaline mineral waters (Borjomi, Slavyanovskaya, Smirnovskaya) are allowed. Gastric contents are continuously aspirated using a nasogastric tube.

| Enzyme replacement therapy is aimed at eliminating impaired absorption of fats, proteins and carbohydrates, which are observed in severe pancreatitis |

As the symptoms of the disease subside, they gradually move on to oral food intake, observing the principle of frequent and fractional feeding. The diet includes pureed porridge, pureed cottage cheese, milk jelly, and from the 5th day

- pureed vegetable soup, vegetable purees,

on the 7-8th day

steamed meatballs and cutlets, boiled fish (table No. 5 (pancreatic) - pureed food ).

After 2-3 weeks,

fruit and vegetable juices are added in small portions in addition to food, and then fresh vegetables and fruits. After 1-1.5 months, the child is transferred to an extended 5p diet (unprocessed food). Patients are prohibited from strong vegetarian broths, meat and fish broths, fatty meats, fish, fried, smoked foods, coarse fiber, spicy snacks, seasonings, canned food, sausages, freshly baked bread, ice cream, cold and carbonated drinks, chocolate. However, an absolute ban on the listed products often causes a feeling of inferiority in patients, therefore, in good condition, it is permissible to resort to “zigzags”. in diet [2, 5].

In the subsiding phase

Pancreatitis is prescribed a gentle diet that provides the physiological need for basic nutrients and energy.

It is recommended to increase protein by 25% of the age norm. The main goal of diet therapy in the remission phase

is aimed at preventing relapse; for this purpose, diet option No. 5 p is used for 5-6 months.

View

[ ]

Drug therapy

The most important thing in the acute period of pancreatitis is the elimination of pain syndrome

.

It is necessary to carry out therapeutic measures aimed at eliminating the causes of pain. The arsenal of medications should include anticholinergic and antispasmodics, analgesics, H2-blockers of histamine receptors, antacids, enzyme and antienzyme drugs [7 – 9]. For analgesic purposes, antispasmodics

- no-spa, papaverine, aminophylline, in combination with simple analgesics, which are administered parenterally in the first days of an exacerbation, and orally as the condition improves.

This allows you to eliminate spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, reduce intraductal pressure and ensure the passage of pancreatic juice and bile into the duodenum. anticholinergic drugs

are used to inhibit gastric and pancreatic secretion (0.1% atropine solution, 0.2% platiphylline solution, 0.1% methacine solution, etc.).

It is of utmost importance in the acute period of pancreatitis. It is necessary to carry out therapeutic measures aimed at eliminating the causes of pain. The arsenal of medications should include anticholinergic and antispasmodics, analgesics, histamine receptor H-blockers, antacids, enzyme and antienzyme drugs [7 – 9]. For analgesic purposes, no-spa, papaverine, aminophylline are prescribed, in combination with simple analgesics, which are administered parenterally in the first days of an exacerbation, and orally as the condition improves. This allows you to eliminate spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, reduce intraductal pressure and ensure the passage of pancreatic juice and bile into the duodenum. Traditionally and successfully during exacerbation of CP, (0.1% atropine solution, 0.2% platyphylline solution, 0.1% metacin solution, etc.) are used to inhibit gastric and pancreatic secretion.

| Clinical examination of children with CP requires systematic stage-by-stage monitoring and quarterly anti-relapse courses of enzyme replacement therapy |

In recent years, modern antisecretory agents have been used to suppress gastric secretion: selective H2-histamine receptor blockers

- ranitidine, famotidine, nizatidine;

proton pump inhibitors

- omeprazole, lansoprazole. These drugs are prescribed 1-2 times a day or once at night for 2-3 weeks.

Reducing the stimulating effect of hydrochloric acid is achieved by prescribing antacid drugs

for 3-4 weeks: gasterin gel (aluminum phosphate gel and pectin for oral use), gelusil and gelusil lacquer (magnesium and aluminum silicate), maalox (aluminum and magnesium hydroxide), megalac (silicic acid hydrous aluminum-magnesium), protab ( aluminum and magnesium hydroxide, methylposiloxane), remagel (aluminum and magnesium hydroxides), topalcan (alginic acid, aluminum hydroxide and magnesium bicarbonate, hydrated silicon), phosphalugel (colloidal aluminum phosphate), Tums (calcium carbonate and magnesium carbonate).

of regulatory peptides is promising

. The drug of choice in the treatment of pancreatitis should be considered octreotide, an analogue of endogenous somatostatin, a humoral inhibitor of exocrine and endocrine secretion of the pancreas and intestines (Table 1). It is also effective for gastrointestinal bleeding of various origins, due to its selective hemodynamic effects [1, 5].

Our experience shows that the use of octreotide makes it possible to quickly relieve pain and reduce enzymatic activity. The course of therapy with octreotide does not exceed 5-7 days. No significant side effects were noted. Already after 1-2 injections in operated patients, the volume of discharge through the drainage from the duct or omental bursa is reduced by 2-4 times. On average, after 3-5 weeks the fistulas close. The patient's condition quickly improves, abdominal pain decreases, intestinal paresis is eliminated, and the activity of enzymes in the blood and urine is normalized.

Detoxification

Infusion therapy is of particular importance during periods of severe exacerbation of pancreatitis.

, aimed at eliminating metabolic disorders against the background of endogenous intoxication. For this purpose, the patient is administered hemodez, rheopolyglucin, 5% glucose solution, 10% albumin solution, fresh frozen plasma, and a glucose-novocaine mixture.

Antienzyme drugs have not lost their importance in pediatric gastroenterology.

- protease inhibitors, the action of which is aimed at inactivating trypsin circulating in the blood. Their purpose is indicated for pancreatitis, accompanied by high fermentemia, fermenturia, for elimination (the phenomenon of enzyme evasion). In our opinion, despite the existing idea in medical and surgical clinics about the low effectiveness of antiproteases even at very high doses, the use of these drugs in pediatrics is especially advisable in the initial stages of pancreatitis, since by suppressing trypsin and kinin activity, they prevent the formation of systemic manifestations (such as a consequence of kinin burst and excess production of interleukins). At the same time, they do not affect the activity of enzymes that have a pronounced lipolytic effect [2, 4, 5, 8].

During the period of relief of exacerbation against the background of restriction of oral nutrition, the administration of parenteral and enteral nutrition is very important.

Mixtures of amino acids (aminosteril, aminosol, alvezin, polyamine and others) are administered intravenously (30-40 drops per minute). It is recommended to add electrolyte solutions (potassium chloride, calcium gluconate 1%), taking into account the acid-base balance. Along with them, fat emulsions are used to bind active lipase and replenish the deficiency of fatty acids in the blood: 10-20% intralipid or lipofundin intravenously with heparin drip at a rate of 20-30 drops per 1 minute, at the rate of 1-2 g of fat per 1 kg of weight .

Enteral nutrition

As dyspeptic disorders disappear, it is advisable to switch to enteral nutrition, the main advantage of which is to reduce the incidence of complications. It should be noted that the more distally nutrients are introduced into the digestive tract, the less the exocrine function of the pancreas is stimulated [6, 7, 10].

Introduce mixtures of amino acids

can be administered enterally (intraduodenal and even intrajejunal) in the morning on an empty stomach, heated to 37°C, in a volume of 50 to 200 ml, depending on age, every other day, for a course of up to 5-7 procedures. This route of administration of amino acids does not cause adverse reactions, is easily tolerated by patients and has a clear therapeutic effect.

Enteral nutrition is provided with mixtures based on protein hydrolysates

with a high degree of hydrolysis with the inclusion of medium chain triglycerides, low-fat dairy-based products and with a modified fat component. They gradually switch to mixtures with a low degree of hydrolysis (Table 2), since these products are absorbed in the intestines without previous fermentation. They can be administered intraduodenally in a warm form through a probe.

Considering that the majority of patients with pancreatitis are diagnosed with significant disturbances in the motor function of the duodenum and biliary tract, often with symptoms of duodenostasis and hypomotor dyskinesia, the use of prokinetics is indicated in the treatment complex.

Of these, it is most advisable to give preference to domperidone and cisapride, as drugs with minimal adverse reactions compared to metoclopramide.

Pathogenetic therapy includes antihistamines

(diphenhydramine, chloropyramine, clemastine, promethazine), in addition to the main effect, they also have sedative and antiemetic effects.

Antibacterial therapy

is indicated to prevent secondary infection, when there is a threat of the formation of cysts and fistulas, peritonitis and the development of other complications.

During the recovery period, it is possible to use essential phospholipids, vitamin complexes, and antioxidants. Due to the deficiency of vitamins, especially group B and C, parenteral administration is recommended for CP, and orally for mild cases. Reparative processes in the pancreas are well stimulated by pyrimidine drugs (pentoxyl, methyluracil), which have inhibitory, anti-inflammatory, and anti-edematous effects [1].

Replacement therapy

A difficult issue in the treatment of pancreatic insufficiency is the choice of enzyme therapy. Enzyme replacement therapy is aimed at eliminating disturbances in the absorption of fats, proteins and carbohydrates, which are observed in severe pancreatitis (hereditary and post-traumatic pancreatitis). In most cases, short-term (no more than 2-4 weeks) administration of enzymes in intermittent courses is indicated. The dose is selected individually until a therapeutic effect is obtained. At first, preference is given to non-combined pancreatin preparations, then after 2-3 weeks, when the exacerbation subsides, enzymes with the addition of bile acids and/or hemicellulase are used. Among the many enzyme preparations, as shown by data from other authors and our own studies, the best effect is achieved by microgranulated enzymes with an acid-resistant shell, obtained using new technologies (lycrease, creon, pancitrate), the characteristics of which are presented in table. 3, 4. They meet the requirements for enzyme preparations: no toxicity, no side effects, good tolerability, optimal action in the pH range 5-7, resistance to hydrochloric acid, pepsin and other proteases, sufficient content of active digestive enzymes.

The effectiveness of enzymes and the adequacy of the dose used is assessed by the dynamics of clinical data (disappearance of pain and dyspeptic syndromes), normalization of the coprogram and the level of enzymes in duodenal contents, blood and urine, and positive dynamics of the child’s body weight. It should be emphasized that in children with CP and hyposecretory type of function,

Despite clinical improvement, restoration of exocrine function does not occur, so the issue of enzyme replacement therapy is decided strictly individually. Long-term uncontrolled use of these drugs suppresses one's own enzyme production via a feedback mechanism. Absolute indications for lifelong prescription of replacement therapy are cystic fibrosis, hereditary pancreatitis, congenital enzyme deficiency, Shwachman syndrome.

Spa treatment

During the period of remission, patients can be referred to sanatorium-resort treatment (Zheleznovodsk, Essentuki, Borjomi, Truskavets, Morshin) and local gastroenterological sanatoriums. Balneotherapy

based on the use of low-thermal and thermal waters of low and medium mineralization. The alkalizing effect of mineral waters prevents early acidification of duodenal contents and induces the production of endogenous cholecystokinin and secretin. Magnesium and calcium ions contained in water, as coenzymes, significantly potentiate the action of secretin and other regulatory peptides, thereby providing a stimulating effect on the degranulation of zymogenic granules and intraduodenal enzyme activity. The course of therapy is 24-30 days, mineral water is prescribed at the rate of 10-15 ml per year of the child’s life per day, starting with a small volume (1/3 of the daily dose) and a single dose in the first days, gradually increasing to a full dose if tolerated well. with three doses.

Mud therapy

(silt, peat, sapropel mud) are carried out carefully due to the risk of exacerbation. In children, segmental application is used at a low temperature, in a course of 8-10 procedures, with simultaneous testing of blood and urine enzymes, and a clinical examination of the patient.

Clinical examination

Clinical examination of children with CP requires systematic step-by-step observation, quarterly anti-relapse courses of enzyme replacement therapy, vitamin therapy, reparatives, hepatoprotectors, and physical treatment.

It is necessary to provide nutritional education to the child and parents and to form traditions of therapeutic nutrition in order to create psychological comfort in the family. Monitoring the condition of the adjacent digestive organs is mandatory (if indicated, an endoscopy should be performed). On an outpatient basis, it is recommended to perform coproscopy at least once every 3 months and monitor the level of amylase in the blood and urine. Once every six months - perform an ultrasound examination of the abdominal organs. If there is no effect from persistent conservative treatment using all modern methods, if complications occur, the patient is observed jointly by a pediatrician and a surgeon to decide on the need for surgical treatment. Literature

1. Diseases of the digestive system in children / Ed. A.A. Baranova, E.V. Klimanskaya, G.V. Rimarchuk. M. 1996; 304 pp.

1. Diseases of the digestive system in children / Ed. A.A. Baranova, E.V. Klimanskaya, G.V. Rimarchuk. M. 1996; 304 pp.

2. Guide to gastroenterology / Under the general editorship. F.I. Komarova, A.L. Grebeneva. M., Medicine, 1996; 3: 719 p.

3. Rimarchuk G.V. Modern aspects of diagnosing chronic pancreatitis in children. Ross. pediatrician. Journal 1998;1: 43-9.

4. DiMagno Yu.P. Determination of severity and treatment of acute pancreatitis. Ross. magazine gastroenterol., hepatol., coloproctol. 1998; 8 (5): 88-90.

5. Khazanov A.I. Treatment of chronic pancreatitis. Ross. magazine gastroenterol., hepatol., coloproctol. 1997; 7 (2): 87-92.

6. Pancreatic surgery, a guide for doctors / Ed. M.V. Danilova, V.D. Fedorov. M., Medicine. 1995; 510 pp.

7. Filin V.I., Kostyuchenko A.L. Emergency pancreatology. St. Petersburg, Peter, 1994; 410 pp.

8. Handbook of a practical physician in gastroenterology / Ed. V.T. Ivashkina, S.I. Rapoport. M., 1999; 426 pp.

9. DiMagno Yu.P. Complications of chronic pancreatitis. Ross. magazine gastroenterol., hepatol., coloproctol. 1998; 8 (5): 90-92.

10. McClave Stephen A. Comparison of the Safety of Early Internal vs Parenteral Nutrition in Mild Acute Pancreatitis. J. of Parenteral and Internal Nutrition 1997; 21 (1): 14-20.

Pancreatitis

Acute pancreatitis

is an inflammatory process of the pancreas, focal or diffuse, which is defined in children as the presence of at least two of the following three criteria:

- abdominal pain compatible with pancreatic origin.

- amylase and/or lipase at least three times the upper normal limits.

- imaging findings suggestive of and/or compatible with pancreatic inflammation.

From an imaging perspective, acute pancreatitis can present in either mild (interstitial edema and pancreatic necrosis) or severe forms (extended fat necrosis, parenchymal necrosis, and hemorrhage).

On ultrasound, the pancreas may show different imaging patterns. Minor forms may have either a completely normal gland (50% of cases) or focal or diffuse enlargement with decreased echogenicity associated with edema (Figs. 10, 11) and poorly defined ribs.

Pancreatic duct dilatation may also be present. Pancreatic ducts with a diameter greater than 1.5 mm in children aged 1 to 6 years, greater than 1.9 mm in children aged 7–12 years, or greater than 2.2 mm in children aged 13–18 years are often associated with the presence of acute pancreatitis.

Peripancreatic fluid is a common finding and is most commonly found in the anterior perinephric space, lesser sac, lesser omentum, and transverse colon.

More severe forms are characterized by different ultrasound patterns depending on the time of examination, the degree of parenchymal necrosis, the presence of hemorrhage and the degree of extrapancreatic diffusion of the inflammatory process. However, severe acute necrotizing pancreatitis and its associated complications are best demonstrated on computed tomography (CT) images as well as MRI. The latter are often additional to ultrasound.

Figure 10 : Transverse (a) and longitudinal (b, c) scan of the pancreatic space. Acute pancreatitis: there is an increase in the volume of the pancreas, which is also characterized by a slightly hypoechoic echostructure and blurred edges due to edema (a, b, asterisk); in addition, there are accumulations of anechoic fluid in the retroperitoneal perinephric space, adjacent to the right kidney (c, arrows).

Figure 11 : Transverse (a) and longitudinal (b, c) scan of the pancreatic space. Acute pancreatitis: there is a significant increase in the volume of the gland, especially the head (b, yellow arrows); in addition, there is a small accumulation of perinephric fluid (a, white arrow).

Chronic pancreatitis

in childhood it is extremely rare and is associated with hereditary and family diseases (hereditary pancreatitis, amino acid chronic pancreatitis and chronic hemorrhagic pancreatitis).

With ultrasound, the volume and echostructure of the pancreas are preserved in 70% of cases. In the remaining 30% we can find some pathognomonic findings: dilation of the Wirsung duct (30%) (Fig. 12), calcifications (10%) (Fig. 13), pseudocysts (10%) (Fig. 14). The latter develop from an acute collection and may take several weeks to form. Most resolve spontaneously, but complications such as infection, bleeding, bile duct obstruction, or even rupture may occur.

Figure 12 : Example case of a 17-year-old boy. Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Multiple hyperechoic macules with posterior attenuation due to intrapancreatic calcifications (left, arrows); in addition, there is a dilated Wirsung canal with signs of a hyperechoic stone inside (right).

Figure 13 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Chronic pancreatitis: a slight diffuse increase in the echostructure of the pancreas with more pronounced hyperechoic spots in the head due to calcifications of the parenchyma.

Figure 14 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Chronic pancreatitis: progressive scan (top line) from the head to the tail of the pancreas with multiple diffuse calcifications and two pseudocyst fluid collections (asterisk). MRI (bottom line) with multiplanar MRCP reconstruction. Chronic pancreatitis in the same patient (see above): Post-contrast axial T1 MR images (center and right) confirmed the above two pseudocyst fluid collections (asterisk) without connection to the pancreatic duct on MRCP (left).

Autoimmune pancreatitis

(AIP) is an increasingly recognized condition, but data in children are limited.

AIP occurs in two forms (types 1 and 2). Type 2 appears to be more common in children and is associated with inflammatory bowel disease and other autoimmune diseases. In adults, the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis type 1 is based on elevated levels of immunoglobulin G4 (IgG4). In children, there may be no increase in IgG4 levels even with typical histology.

Ultrasound can show diffuse or segmental enlargement of the pancreas with reduced echogenicity associated with phlogosis, as well as irregular narrowing of the pancreatic duct, compressed by the parenchyma of the gland.

Symptoms of reactive pancreatitis

An infectious disease can provoke reactive pancreatitis.

This form of the disease is most often observed in children of any age. Almost any infectious disease can provoke reactive pancreatitis (poisoning followed by gastroenteritis, acute respiratory viral infections, acute respiratory infections).

The reason for its occurrence in infants is the too early introduction of meat dishes and various seasonings from the adult table into the diet, which complicates the work of the immature pancreas. Symptoms of reactive pancreatitis in children:

- The nature of the pain is sharp, tingling. The pain decreases if the child sits down, leaning slightly forward.

- Localization of pain is above the navel.

- Vomiting of stomach contents, severe nausea.

- Low-grade fever (37? C) in the first hours of the disease.

- Severe diarrhea.

- White coated tongue, thirst and a feeling of dry mouth.

- Deterioration in general health, tearfulness.

- Increased gas formation.

Diagnosis is carried out using ultrasound of the abdominal organs, laboratory tests of stool and blood biochemistry.

Pancreatic insufficiency

Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a recessive autosomal inherited disease that may not show any significant imaging findings in the early stages but can eventually lead to exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

The pancreatic parenchyma is replaced by fibrosis and fat, so that in later stages it appears atrophic, small and hyperechoic (Fig. 15). Pancreatic fatty infiltration into the CF is associated with increased softness on spot shear wave elastography (pSWE) (Fig. 16); this parameter can be used to monitor pancreatic involution in this progressive disease.

In addition, small retention cysts (pancreatic cystosis), usually no more than 3 mm, and areas of decreased echogenicity due to fibrosis may be detected.

Figure 15 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Cystic fibrosis: The pancreas appears diffusely hyperechoic compared to the liver due to fatty infiltration.

Figure 16 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas. Measuring shear wave velocity in the head of the pancreas in a patient with cystic fibrosis.

Pancreatitis is a rare complication among patients with CF and should be considered in the presence of suggestive clinical signs.

Finally, ultrasound of the pancreas in children with cystic fibrosis should always be integrated with liver evaluation, since the primary pathology can often coexist with biliary cirrhosis (Fig. 17).

Figure 17 : Longitudinal ultrasound examination of the right lobe of the liver. Cystic fibrosis: diffuse echostructural changes in the liver with alternating hypoechoic and hyperechoic areas. Shear wave velocities are also measured.

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is a rare autosomal recessive multisystem disease characterized by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, impaired hematopoiesis, and a predisposition to leukemia.

Other clinical features include skeletal, immunological, hepatic and cardiac diseases. On ultrasound, diffuse increased echogenicity of the pancreas associated with fatty infiltration is typical of SDS (Fig. 18).

Figure 18 : Transverse epigastric ultrasound of the pancreas (a, b). Shwachman-Diamond syndrome: The pancreas is diffusely hyperechoic compared to the adjacent left lobe of the liver due to significant fatty infiltration.

Periods of increased risk

There are several periods when a child is most likely to have gland dysfunction:

- when introducing complementary foods;

- changing breastfeeding to artificial feeding;

- at the beginning of kindergarten;

- during the transition from kindergarten to school;

- during puberty.

As a rule, during these periods the environment, nutrition, and emotional background of the child change. All of these factors can increase the risk of digestive system problems. Hormonal levels also have an important impact on health.

During such periods, it is recommended to closely monitor the child’s condition. If he experiences any symptoms associated with damage to the pancreas, he should consult a doctor and undergo an examination. To determine the nature and extent of organ damage, an abdominal ultrasound should be performed, as well as laboratory research methods should be applied.

Tumors

Primitive neoplasms of the pancreas in childhood are quite rare. These tumors can be divided into three main groups: exocrine, endocrine and cystic lesions

.

Secondary lesions of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma, neuroectodermic tumors and retroperitoneal neoplasms (neuroblastoma) are more common.

Pancreatoblastoma is the most common pancreatic tumor in young children. It is an infantile-type pancreatic carcinoma with histological similarities to normal fetal pancreas at 8 weeks' gestation and demonstrates elevated alpha-fetoprotein levels in one third of cases.

On ultrasound, most pancreatoblastomas appear as well-defined heterogeneous lesions with solid and cystic components. Cystic formations are hypoechoic with hyperechoic internal septa. Sometimes a hypoechoic solid mass is found. Congenital cases of pancreatoblastoma in combination with Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome have been described, and they are predominantly cystic.

Although pancreatoblastoma is considered the most common malignancy in children, recent studies have shown that solid pseudopapillary epithelial neoplasm (SPEN) is the most common pancreatic tumor in children.

SPEN is a lesion with low malignant potential that most commonly affects women of reproductive age. On ultrasound, the tumor usually appears as a well-defined large mass with varying characteristics depending on the presence of cystic and solid components, intratumoral hemorrhage, and calcifications. The fibrous capsule may be identified as an echogenic or, less commonly, hypoechoic rim.

Neuroendocrine tumors arise from pancreatic islet cells. On ultrasound, insulinomas are usually round or ovoid, hypoechoic with a hyperechoic rim. Tumors with larger islet cells, usually malignant insulinomas, gastrinomas (or other neuroendocrine tumors), may have a heterogeneous ultrasound appearance depending on the presence of cystic areas, hemorrhage, necrosis, and calcifications.

Nesidioblastoma is a similar neoplastic disease of the pancreas, characterized by new differentiation of the islets of Langerhans from the pancreatic ductal epithelium with subsequent hyperproduction of insulin. Ultrasound shows increased echogenicity and volume of the pancreas. Nesidioblastosis is often associated with hypoglycemia and Beckwith–Wiedermann syndrome.

Moreover, the pancreas may be involved in non-Hodgkin lymphoma, especially large cell lymphoma and sporadic Burkitt lymphoma. On ultrasound, these tumors are very hypoechoic and can variably appear as single or multiple lesions or diffuse infiltration of the pancreas.

About the disease

Due to improper nutrition, pancreatic cells die and cause inflammation.

Pancreatitis is a very dangerous pathology of the pancreas, the inflammatory process in which can result in serious complications. Due to dietary errors and other problems, pancreatic cells die, causing an inflammatory process in the surrounding tissues.

Violation of the functions of the gland leads to stagnation of the juice it produces, which, instead of entering the duodenum, causes swelling of the gland and destruction of its tissues. A lack of pancreatic juice enzymes means that nutrients do not enter the intestines and do not stimulate food digestion.

The carefully adjusted system of providing nutrition to the child's body is disrupted. In acute cases, the pain of pancreatitis can be so severe that the patient is subjected to painful shock. Types of pancreatitis in children:

- Acute form of the disease. Occurs after injury, poisoning, as a consequence of a viral infection.

- Chronic form of pancreatitis. Occurs after untreated acute pancreatitis, violation of doctor’s recommendations regarding diet and treatment, and is characterized by frequent exacerbations.

- Reactive form of pancreatitis. It occurs as a reaction to dysfunction of the gastrointestinal tract, as a complication of inflammatory processes in the abdominal organs. After treatment of the underlying disease, the prognosis is favorable.