GERD - queen of the night

Oleg Alksandrovich Sablin , professor, doctor of medical sciences:

– Good afternoon, Moscow, good afternoon, St. Petersburg is our big country. The topic of our conversation today is gastroesophageal reflux disease. And we called our report “GERD – the queen of the night.” I think as our report progresses it will become clear why. Dear colleagues, you all know very well that gastroesophageal reflux disease includes a non-erosive form - this is about 60-70% of all patients, an erosive form of the disease - 20-35% and complications, which account for 6 to 12% of all patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease. And it is important that complications currently include both adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and the background against which it occurs - Barrett's esophagus, not to mention ulcers and esophageal stricture.

Barrett's esophagus, let's say, is an obligate precancerous condition - a common disease. And in general, if we take statistics around the world, then this is about one per 100 people in the population, so you see, in the USA there are about seven people, if we take our Europe, then this is about one to three people per 100 people - this is a lot. It is clear that the disease has not been diagnosed in our time. All over the world, there is an increase in the relative frequency of esophageal adenocarcinoma, not the absolute, but the relative frequency. And you see, here he prevails over all other cancers. But if we take our St. Petersburg statistics - we have been monitoring this condition for a long time - then we have about six to seven people who last for about 10 years per 100 thousand population.

A very important point is carcinogenesis in Barrett's esophagus. We must all, including practicing physicians, understand that if a patient is diagnosed with adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, then our colleague somewhere did not diagnose Barrett’s esophagus, because almost all adenocarcinomas of the esophagus develop against the background of Barrett’s esophagus. Esophageal adenocarcinoma is most often preceded by intraepithelial neoplasia. That is, there is no need to immediately grab a patient with Barrett's esophagus by the scruff of the neck and drag him with some endoscopic or surgical methods to destroy this Barrett's esophagus. And high-grade dysplasia also does not always immediately turn into adenocarcinoma. But with a fairly high frequency it occurs in every 10th person per year. The symptoms of the clinical picture of gastroesophageal reflux disease certainly matter. And if a patient is bothered by frequent and intense heartburn, especially nighttime symptoms in this patient, and a long history of the disease, this significantly increases the risk of esophageal cancer. You see, about 44 times.

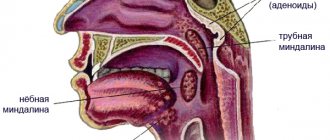

The pathogenesis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, I think, is well known to all of you, and our highly respected Italian colleague has already addressed this. I will say this in just a few strokes. We know that there is clearance of the esophagus, which cleanses, let’s say, the cavity of the esophagus from the acid, bile and other toxic factors that are thrown there. That is, there is primary peristalsis, and secondary peristalsis is very important - what allows you to clean the esophagus. Saliva is, of course, important, since its pH is close to alkaline. The state of the gastroesophageal junction is also an important factor in the pathogenesis of GERD. The phrenoesophageal ligament is very clearly visible on this slide. Also, of course, her condition is important in the pathogenesis of this disease. An acute angle of His is when the esophagus enters the stomach not at the very top, but slightly below. Of course, the gastric fold and gastric evacuation, as well as the condition of the crural muscles, are important.

Reflux mechanisms are always in conflict with antireflux mechanisms. And, of course, esophageal motility disorders, which we must diagnose, are most important in the pathogenesis of this disease. And that is why in some situations it is necessary to carry out manometry of the esophagus, at least it is necessary to carry out x-rays of the esophagus to exclude achalasia and any other disorders of motility of the esophagus. The condition of the lower esophageal sphincter is certainly important. Its damage and hiatal hernia are important factors in pathogenesis. Stomach: slow gastric evacuation and postprandial acid pocket also occur, and this also contributes to the occurrence of these lesions in the distal esophagus.

We also know well that there are additional factors in the pathogenesis of GERD - obesity, universally accepted smoking, alcohol abuse, increased esophageal perception, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Tissue resistance of the esophageal mucosa is important. And the more we deal with this problem, the more often the idea comes that Barrett’s esophagus is, after all, a metabolic problem, that it is a metabolic problem of impaired tissue resistance of the esophageal mucosa. Of course, scleroderma, pregnancy, some heterogeneous effects and the use of drugs that affect the tone of the smooth muscles of the esophagus. And besides these traditional moments that initiate gastroesophageal reflux, nocturnal factors in the pathogenesis of GERD are also identified. These include the fact that the peak of gastric secretion occurs in the evening and night, nocturnal acid breakthroughs, which have already been discussed today, slow night evacuation, significantly reduced night salivation, lack of swallowing during deep sleep, decreased pressure of the upper esophageal sphincter during sleep. But at the same time, the pressure of this upper esophageal sphincter is maintained during the rapid eye movement phase.

The pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter does not change during sleep, and this is an important point that protects a person from aspiration of stomach contents. Transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter also do not occur during deep sleep. Esophageal clearance is absent during deep sleep and occurs during brief awakenings. This is a very important point, which in some situations contributes to and initiates gastroesophageal reflux disease. Acid that enters the esophagus certainly moves more proximally in the supine position. And eating immediately before bedtime has the most pathogenetic effect. Well, it is clear that our patient cannot always wake up, sometimes he is lazy or simply cannot take the medicine during sleep.

What diseases and conditions can we associate with nocturnal gastroesophageal reflux? Of course, the most dangerous condition, which is not so often detected, is adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, Barrett's esophagus, erosive esophagitis and, in addition, insomnia, intermittent sleep, that is, various insomnia disorders, increased daytime activity, excessive daytime sleepiness, low quality of life, recurrent pneumonia and aspiration, nocturnal asthma, nocturnal laryngospasm. A very important point is that Barrett’s esophagus, a condition that is initiated as a consequence of the development of adenocarcinoma, occurs more often when intestinal contents reflux into the esophagus. Here in this Wolfgarten slide we see that the average gastric pH is generally the same throughout the day in both patients with Barrett's esophagus and healthy individuals. But if we take the bilirubin exposure determined in this study using the Bilitec device, we see that both in the supine and standing positions, of course, this bilirubin exposure is higher in a patient with Barrett's esophagus. That is, Barrett's esophagus - and we all know this well - is an adaptation of the intestinal mucosa to these constant intestinal reflux. But it is very important - and it was also perfectly shown in this work - that in the supine position, these reflux of intestinal contents more often occur in patients with Barrett's esophagus (and this is most often at night).

You see, middle bar, right chart, patients with esophagitis have significantly fewer symptoms. This is associated precisely with this intestinal reflux. Nocturnal reflux certainly reduces quality of life compared to daytime symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. And this is clearly visible in these diagrams. More than half of patients with nocturnal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease suffer from sleep disturbances, and this is logical and understandable. They are much more likely to have difficulty falling asleep, wake up at night, and have nightmares. There is also the opposite effect. Here's an interesting 2013 study that showed that patients with sleep apnea, which is often triggered by snoring, have an 80% increased risk of Barrett's esophagus compared to patients without sleep apnea. And the risk of developing Barrett's esophagus did not depend on age, gender, history of GERD and smoking. And, of course - this is one of the main slides - esophageal adenocarcinoma is more often detected against the background of nocturnal symptoms of the disease. We see that adenocarcinoma is more often detected during nocturnal symptoms of the disease. Not adenocarcinoma of the cardia, not squamous cell carcinoma, but adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. This has also already been said that, of course, proton pump inhibitors and drugs with the most maximum (...)(10:19) are most effective for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease. This is evidenced by a completely recent updated Cochrane review from 2013 by van Pinxteren. I think it was before this in 2008. And here it is shown that this is the most effective group of drugs for the treatment of both non-erosive forms of the disease and for the treatment of erosive forms of GERD.

Proton pump inhibitor therapy is associated with a reduced risk of dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus, and this is also a fairly well established fact. If we take the group of proton pump inhibitors and take the position of evidence-based medicine, then, of course, Rabeprazole has certain and quite significant advantages compared to both proton pump inhibitors, let’s say, of previous generations, and to Esomeprazole. This meta-analysis demonstrates this. There is an interesting feature of the drug "Rabeprazole", which was revealed in studies - that it is more effective than "Esomeprazole". 20 milligrams of Rabeprazole turned out to be more effective than 40 milligrams of Esomeprazole in stopping nighttime secretory activity of the stomach. And we see that pH > 3 and > 4 - its percentage of the time at night was higher on Rabeprazole, it must be admitted, with the same percentage during the day. Evening administration of Esomeprazole is more effective in relieving nocturnal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. And, of course, Rabeprazole turned out to be more effective, and there is a lot of evidence of this. It turned out to be more effective. And in this case, it was compared with Pantoprazole in comparison with first-generation proton pump inhibitors.

It is shown here that, in principle, two days are enough for the drug “Rabeprazole” to successfully correct the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in most cases compared to placebo. How can this be explained? To a certain extent, due to the fact that Pantoprazole is activated at 3.8 pH, Lansoprazole - at 3.9, Omeprazole and Esomeprazole - at 4 pH units, and Rabeprazole is activated already at pH 5. This is important moment, because this drug has the property of being activated much earlier than other proton pump inhibitors. This matters, and they write about this, that if you take the structure of parietal cells, then this drug allows you to block both the work of young parietal cells and old ones, let’s say, which are already moving to the bottom of the fundic gland, and the pH produced by them is slightly higher than that produced by young cells. And it is possible that it is “Rabeprazole” that blocks both young parietal cells and old ones. Well, Rabeprazole blocks both cells. And perhaps this is due to the fact that it works better, and in conditions of histamine secretion, when the drug is used before meals, then the patient eats, and hypergastrinemia occurs, secretion increases and active pumps are blocked. Well, perhaps it blocks pumps that are not yet active and are not 100% active.

A very important study showing the role of proton pump inhibitors in the prevention of esophageal adenocarcinoma. This is a prospective study - 5 years, and a fairly large cohort of patients. It was shown that no patients on proton pump inhibitor treatment experienced regression of Barrett's esophagus while using proton pump inhibitors. But use of proton pump inhibitors was associated with a 75 percent reduction in the risk of tumor progression in patients with Barrett's esophagus. And the same effect was not found with an H2-histamine blocker. And it is very important that the use of a proton pump inhibitor is necessary for 90% or more of the observation time. And it is then that this is combined with a lower risk of tumor progression (the occurrence of adenocarcinoma or high-grade dysplasia) than the use of proton pump inhibitors not with such frequency.

Dose, also an important finding of this prospective study, did not affect the risk of progression. This study also showed some benefits. And Rabeprazole turned out to be even more effective than Omeprazole and Esomeprazole. Of course, these are unlikely to be any special properties of Rabeprazole, although why not. I think there will be a lot of research on this. But here’s an interesting fact: “Rabeprazole” turned out to be 3 times more effective than “Omeprazole” and “Esomeprazole” for this purpose, in terms of preventing adenocarcinoma. And thus, dear colleagues, all the studies that have been conducted on Rabeprazole have shown that it is more effective in relieving the nocturnal symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease compared to other proton pump inhibitors. Rabeprazole therapy is more effective in preventing Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma compared to other proton pump inhibitors. Well, you see, there is such a beautiful cactus flower here, which is called “Queen of the Night,” but it is very prickly, just like the disease GERD. Thank you very much for your attention.

Sore throat and gastritis: an unobvious connection

This will probably seem “strange,” but a sore throat can actually be a consequence of gastritis, or more precisely, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Pain in this case appears “on its own”, without other traditional signs of acute respiratory infections. But rinsing, inhaling or taking antibiotics obviously doesn’t make it better. So how not to confuse acute respiratory infections and GERD? And what else does pathology threaten?

What is GERD

Gastroesophageal reflux disease is a chronic pathology with a relapsing course, characterized by periodic spontaneous reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus and larynx, and the development of lesions resembling chemical burns.

This type of reflux is felt as heartburn or a sour taste after a burp, and most often appears after eating, during sleep, or when bending the body forward.

At the same time, it also occurs in a healthy body, after eating. True only if it is not accompanied by unpleasant sensations and extra-esophageal symptoms.

These symptoms include:

- pain behind the sternum, radiating to the neck, lower jaw, interscapular area and left half of the chest, which can simulate angina pectoris;

- sore and sore throat, hoarseness, laryngitis;

- as well as cough, shortness of breath and severe bronchospasm, reminiscent of asthma.

As you can see, GERD successfully disguises itself as several fundamentally different diseases, often leading clinicians down a false diagnostic and therapeutic path.

For example, “provokers” of coughing and choking are often sought among allergens. Chest pain leads to a cardiologist. Laryngitis is treated with antibiotics.

Such treatment, however, will not give any tangible results. After all, the true cause of the pathology lies in excessive acidity of the stomach and insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter (“flap” between the esophagus and stomach).

How to check for GERD

The classic way to detect GERD is 24-hour intraesophageal pH-metry.

However, the method cannot be used in a screening format and for self-diagnosis, since it requires the installation of a nasopharyngeal tube and is associated with the psychological experiences of the patient.

Unfortunately, medicine does not yet know another reliable and non-invasive way to assess acidity in the esophagus. However, GERD can be indirectly assumed using the Gastrocomplex blood test.

The complex includes the definition:

- Gastrina-17,

- Pepsinogen (I, II and their ratios)

- and antibodies to H. pylori,

which allows, with a high degree of efficiency, to detect the presence of hyperacid (with high acidity) gastritis and Helicobacter pylori infection, which are the “basis” of GERD.

In addition, the analysis is widely used to identify atrophic gastritis and the risk of gastric oncology.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) questions and answers

print version- home

- >

- For patients

- >

- Doctors' advice

- >

- Proceedings of the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases

Where can I get tested?

| If treatment doesn't help | Popular about gastrointestinal diseases | Stomach acidity |

On the website GastroScan.ru in the Literature section there is a subsection “Popular Gastroenterology”, containing publications for patients on various aspects of gastroenterology.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) questions and answers

The International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases (IFFGD), USA, has prepared a number of materials on functional gastrointestinal disorders for patients and their families.

This material is devoted to gastroesophageal reflux disease. Originally written by Joel Richter, Philip O. Katz, and J. Patrick Waring, edited by William F. Norton.

In 2010, an updated version was prepared by Ronnie Fass. Even a little knowledge can make a big difference

Introduction

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, abbreviated as GERD, is a very common disease that affects at least 20% of adult men and women in the United States. It is also common in children. GERD often goes unrecognized because its symptoms can be misinterpreted and this is unfortunate, since GERD is usually treatable, and if left untreated, serious complications can occur.

| Esophageal-gastric junction (O.B. Dronova and others) 1 – longitudinal muscles of the esophagus 2 – circular muscles of the esophagus 3 – diaphragm 4 – cardiac notch |

The purpose of this publication is to gain a deeper understanding of issues such as the nature of GERD, its definition and its treatment. Heartburn is the most common, but not the only symptom of GERD. (The disease can even be asymptomatic). Heartburn is not a specific symptom for GERD and may result from other diseases of the esophagus or other organs. GERD is often treated independently, without consultation with specialists, or treated incorrectly. GERD is a chronic disease. Her treatment must be on a long-term basis, even after her symptoms are under control. Proper attention must be paid to changes in daily life habits and long-term medication use. This can be done through follow-up and patient education. GERD is often characterized by painful symptoms that can significantly impair a person's quality of life. Various methods are used to effectively treat GERD, ranging from lifestyle changes to medications and surgery. For patients suffering from chronic and recurrent symptoms of GERD, it is important to obtain an accurate diagnosis and receive the most effective treatment available.

What is GERD?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease or GERD is a very common condition. Gastroesophageal

means that it relates to both the stomach and the esophagus.

Reflux

- that there is a reverse flow of acidic or non-acidic stomach contents into the esophagus. GERD is characterized by its symptoms and can develop with or without damage to the tissues of the esophagus, resulting from repeated or prolonged exposure of the esophageal mucosa to acidic or non-acidic stomach contents. If tissue damage is present, the patient is said to have esophagitis or erosive GERD. The presence of symptoms without visible tissue damage is called non-erosive GERD. GERD is often accompanied by symptoms such as heartburn and sour belching. But sometimes GERD occurs without visible symptoms and is detected only after complications become obvious.

What causes reflux?

After swallowing, food passes down the esophagus. Once in the stomach, it stimulates cells that produce acid and pepsin (an enzyme), which are necessary for the digestion process. A bundle of muscles at the bottom of the esophagus, called the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), acts as a barrier to prevent stomach contents from flowing back (reflux) into the esophagus. To allow the swallowed portion of food to pass into the stomach, the LES relaxes. When this barrier relaxes at the wrong time, when it is weak, or when it is otherwise not effective enough, reflux can occur. Factors such as bloating, delayed stomach emptying, a significant hiatal hernia, or too much stomach acid can also trigger acid reflux.

What Causes GERD?

It is not known whether there is a single cause of GERD. Failure of the esophageal defenses to resist aggressive gastric contents entering the esophagus during reflux can lead to tissue damage to the esophagus. GERD can also occur without damage to the esophagus (approximately 50-70% of patients have this form of the disease). Gastroesophageal reflux occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter somehow fails to cope with its obturator function. Reflux also occurs in healthy people who do not have GERD. Normally, they do not cause consequences, except for rare heartburn. In people with GERD, reflux causes frequent symptoms or damage to the tissue of the esophagus. Some, but not all, patients with a hiatal hernia have GERD and vice versa. With a hiatal hernia, part of the stomach can enter the chest area from the abdominal cavity, extending above the diaphragm. The diaphragm is a muscle that separates the chest (containing the esophagus) from the abdominal cavity (containing the stomach). A leaky diaphragm can affect the ability of the LES to control acid reflux. A hiatal hernia may reduce the sphincter pressure needed to maintain the antireflux barrier. Even when the LES and diaphragm are intact and functioning normally, reflux is still possible. The LES may relax after large meals that stretch the upper part of the stomach. When this occurs, there may not be enough LES pressure to prevent reflux. In some patients, the LES is too weak or cannot hold enough pressure to prevent reflux when intra-abdominal pressure increases. Severity of esophageal damage - The severity of GERD depends on the frequency of reflux, the amount of time that refluxed gastric contents remain in the esophagus, and the amount of acid that enters the esophagus.

What are the most common symptoms of GERD?

Symptoms of GERD vary from person to person. Most people with GERD have mild symptoms, no visible evidence of tissue damage, and a low risk of complications. Chronic heartburn is the most common symptom of GERD. Sour burping (when sour reflux reaches the mouth) is another common symptom, sometimes also with a sour or bitter taste.

What other symptoms besides heartburn are symptoms of GERD?

There are many symptoms that could be symptoms of GERD. These include burping, difficulty or pain when swallowing, heartburn, or sudden excess saliva. An alarming symptom that requires consultation with a doctor is dysphagia (the feeling of food getting stuck in the esophagus). Other symptoms of GERD: chronic sore throat, laryngitis, coughing, chronic cough, gum inflammation, erosion of tooth enamel. Small amounts of acid may enter the windpipe or lungs and cause irritation. Hoarseness in the morning, sour taste, halitosis (bad breath) may indicate the presence of GERD. Chronic asthma, cough, shortness of breath and extracardiac chest pain, sometimes mistaken for angina, may also be associated with GERD. In patients with these symptoms, typical symptoms of GERD, such as heartburn, are often less common or not present at all. Pain or pressure in the chest may indicate acid reflux. It is important that this type of pain or discomfort requires urgent medical attention in order to identify possible cardiac diseases, which should be excluded first. After a two-week trial of proton pump inhibitors (prescription drugs that inhibit stomach acid secretion) prescribed by your doctor, your symptoms may improve or improve. This is considered a sign that GERD is the likely cause. The diagnosis of GERD can be confirmed by daily pH monitoring, which measures the acidity of reflux in the esophagus as well as in the larynx.

What is heartburn?

Most people describe heartburn as a burning sensation in the center of the chest behind the breastbone. This sensation may move up to the throat. Heartburn is usually caused by acid reflux into the esophagus. The lining of the esophagus is much more sensitive to acid than the lining of the stomach, so acid entering the esophagus causes a burning sensation. In patients with GERD, persistent heartburn can be painful, can distract from daily activities, and can wake you up at night.

Is heartburn dangerous?

Heartburn is a symptom. And very common. It is estimated that more than 44% of American adults experience heartburn at least once a month. If heartburn occurs regularly, the acid that causes heartburn has the potential to injure the lining of the esophagus and cause ulcerations, which can cause discomfort or even bleeding. Also, as a result of the impact of chronic or frequent acid reflux on the esophagus, strictures can form - narrowings of the esophagus, sometimes leading to scarring. Patients with strictures have difficulty swallowing food. The severity, frequency, or intensity of symptoms cannot be used to differentiate between patients with erosive and non-erosive GERD. However, heartburn that occurs more than once a week, becomes increasingly severe, or starts at night and wakes you from sleep may be a sign of a more serious condition, in which case it is recommended to consult a doctor. Atypical symptoms such as hoarseness, difficulty breathing, chronic cough, or non-cardiac chest pain may also require a visit to the doctor to determine if they are related to GERD. Even occasional heartburn, if it continues for five years or more, or associated dysphagia, can signal a serious illness. Patients who suffer from chronic heartburn over a long period of time are at greater risk of developing complications, including strictures and a potentially precancerous condition of the esophageal epithelium called Barrett's esophagus.

What over-the-counter medications can treat heartburn?

Many of the medications used to treat heartburn are available without a prescription. These are: antacids - drugs that neutralize acid (for example, sodium bicarbonate, calcium carbonate, aluminum hydroxide, magnesium hydroxide), alginic acid preparations (for example, Gaviscon, Foamicon), which form a foam barrier that prevents reflux, as well as H2-blockers in reduced quantities. doses, for example, Pepcid, Tagamet, Zantac, Axid), which reduce acid production; they are available in higher doses for the treatment of GERD by prescription. These medications are useful for relieving occasional heartburn, especially if it is triggered by certain foods or specific events. Antacids and alginic acid preparations give the fastest effect. H2 blockers provide more lasting relief and are most useful if you know what is causing your heartburn, such as spicy foods. Prilosec OTC, Zegerid OTC, and Prevacid 24HR are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and are currently available over the counter. They are more powerful than the medications listed. They are recommended to be taken daily for 14 days. They are not intended to be taken as needed. If symptoms do not improve or if they recur after you stop taking proton pump inhibitors, you should consult your doctor. Over-the-counter medications provide only temporary relief of symptoms. They do not prevent recurrence of symptoms or ensure healing of the esophagus. They should not be taken regularly as a substitute for prescription medications - they may cause a more serious condition to go undetected. If there is a need to take such drugs regularly, for more than two weeks, it is necessary to consult a doctor to establish a diagnosis and prescribe appropriate treatment.

How is GERD diagnosed?

The diagnosis of GERD must be made by a doctor. It is usually determined based on symptoms only. GERD may, however, occur with atypical symptoms or even without visible symptoms. Diagnostic tests may be used to confirm or exclude a diagnosis of GERD or to detect atypical symptoms. Tests can also be used to confirm or rule out complications associated with GERD, such as inflammation of the lining of the esophagus, strictures, or Barrett's esophagus.

What tests are used to diagnose GERD?

Diagnostic tests are used to confirm or exclude GERD or as part of preoperative investigations. One of the tests is a proton pump inhibitor test, or PPI for short, a drug used to treat GERD. Symptom relief after two weeks of PPI therapy has been found to correlate with a diagnosis of GERD. Other studies:

- endoscopy;

- esophageal manometry;

- daily monitoring of esophageal pH;

- impedance-pH-metry of the esophagus.

Endoscopy

is used to detect complications such as inflammation (esophagitis), strictures, or Barrett's esophagus.

Endoscopy is an extremely safe procedure. A thin fiber optic tube is used to examine the esophagus, stomach, and upper small intestine. Some patients are given a sedative to make the procedure comfortable. To detect degeneration of esophageal tissue (Barrett's esophagus), a tissue sample may be taken from the lower part of the esophagus for analysis. This is done painlessly using a biopsy. During the esophageal manometry

, pressure is measured along the entire length of the esophagus and in the area of the lower esophageal sphincter. For this, a thin tube (

) is inserted through the nose into the esophagus.

This test allows the doctor to determine how well the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter are functioning. 24-hour esophageal pH monitoring

uses a thin tube (pH probe) inserted through the nose into the esophagus or a wireless pH capsule attached to the lining of the lower esophagus during endoscopy.

Both devices measure acidity in the esophagus, a pH probe - for 24 hours, a pH capsule - for 48. During this study, the patient lives a normal life and engages in his usual activities. Measurements reveal the presence of reflux, its relationship with symptoms, the frequency of reflux, and the amount of acid entering the esophagus during reflux. During impedance pH testing of the esophagus,

a thin tube (ZpH probe) is inserted through the nose into the esophagus. Such a probe can detect any type of reflux from the stomach into the esophagus (acidic or non-acidic). The measurements can determine whether a given reflux is acidic or non-acidic, whether it causes symptoms, how often refluxes occur and how many there are in total.

Is there a connection between GERD and esophageal cancer?

A small percentage of patients with GERD experience a complication that is a potentially precancerous condition. This complication is called Barrett's esophagus. With this disease, degeneration of the tissue of the esophageal mucosa occurs and this is a risk factor for the development of esophageal cancer. The number of patients who develop Barrett's esophagus is relatively small, about 10% have GERD, and only 0.5% of these develop esophageal cancer within a year. Barrett's esophagus is most common in people who have had heartburn for a long time (more than 5-10 years), over the age of 50, and in Caucasian men. Regular endoscopic examinations are now recommended for patients with Barrett's esophagus. Not all patients with frequent or severe heartburn develop Barrett's esophagus. Some people suffer from heartburn but do not have any damage to the esophagus, while others have damage to the esophagus but do not have heartburn. However, for patients with chronic GERD or frequent symptoms, it is advisable to see a doctor to evaluate the situation and, taking into account the results of endoscopy, determine whether they have Barrett's esophagus. There is currently no convincing evidence that GERD is a risk factor for the development of esophageal cancer in the absence of Barrett's esophagus. However, it makes sense for patients with GERD to periodically visit a doctor to assess the optimality of treatment.

Is there a connection between GERD and stomach infection associated with ulcers?

Infection with the bacteria Helicobacter pylori

can cause peptic ulcers (duodenal or gastric ulcers).

However, there is no convincing evidence that Helicobacter pylori

can cause GERD.

Can diet or certain foods cause GERD?

Diet alone cannot cause GERD. However, gastroesophageal reflux and the heartburn it causes can be aggravated by certain foods. The most common causes of concern are chocolate, onions, fried foods, fatty foods, mint, alcohol, caffeine, carbonated drinks and acidic foods. Spicy foods and citrus products can worsen heartburn. Large amounts of fatty foods that slow gastric emptying, eaten late in the evening, can contribute to nighttime heartburn. Alcohol can relax the lower esophageal sphincter and thereby increase reflux.

Can stress make reflux worse?

More than 50% of patients complain that stress worsens heartburn. Studies using 24-hour pH monitoring have shown that the presence or absence of stress does not affect the incidence of reflux. However, stress can make the esophagus more sensitive to acid. Perception of the frequency and severity of symptoms increases during times of stress. Controlling stress appears to be beneficial.

How is GERD treated?

GERD is a relapsing and chronic disease for which long-term drug therapy is usually effective. It is important to recognize that chronic reflux does not go away on its own. There is no cure for GERD yet. Therefore, GERD requires long-term and adequate therapy. Treatment of gastroesophageal reflux is usually initiated by patients when individual symptoms intensify or when complications of GERD develop without noticeable symptoms. The goals of treatment are:

- controlling symptoms so the patient feels better;

- cure inflammation and ulceration of the esophagus;

- control or prevent complications such as strictures;

- maintaining GERD symptoms in remission so that they do not affect or have minimal impact on the daily life of patients.

Treatment may include lifestyle changes, drug therapy, surgery, or a combination of these. Lifestyle changes.

It is necessary to avoid factors that can aggravate symptoms, so it is necessary to: reduce the intake of fats (they delay gastric emptying and reduce the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter), reduce the intake of caffeine, chocolate, onions, mint and carbonated drinks (they reduce LES pressure), and also stop or reduce your intake of citrus fruits and tomatoes (acidic foods increase the sensitivity of the esophagus to acid), increase your protein intake (it can speed up gastric emptying).

Alcohol and smoking also negatively affect LES pressure and acid secretion. For 3-4 hours after eating, it is undesirable to take a horizontal position (stretching the stomach stimulates relaxation of the LES). Avoid bending or doing exercises that may increase intra-abdominal pressure. Raising the head of the bed 6 inches can help clear reflux acid from your esophagus more quickly at night. Sleeping on one side (usually the left) can help reduce the amount of reflux. Try to get a good night's sleep by doing calm activities before bed and going to bed at the same time. Tell your doctor about all the medications you take. Some of the medications may make symptoms worse. Here are some examples: nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (used to treat arthritis and general inflammation) can cause direct damage to the esophagus; sedatives and calcium channel blockers (used mainly to treat high blood pressure and angina) relax the LES; sedatives slow down gastric emptying and provoke reflux; alendronate sodium (used to treat osteoporosis), if not taken exactly as directed and with too much water, may cause damage to the esophagus or an increase in reflux. Medicines

.

The following groups of drugs are used to treat GERD: prokinetics, H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Prokinetic drugs such as metoclopramide (Cerucal) are primarily intended to speed up gastric emptying. Metoclopramide is not prescribed as the sole treatment for GERD, but only as an adjunct to other antireflux medications in patients with gastroparesis. The drug may cause neurological side effects that may not go away when you stop taking the drug. H2 blockers (famotidine, cimetidine, ranitidine, nizatidine) reduce the amount of acid produced in the stomach. At prescription doses, they relieve symptoms and heal the esophagus in about 50% of patients. However, remission is maintained in only 25% of patients using H2 blockers. Proton pump inhibitors inhibit acid secretion in the stomach. They allow you to quickly get rid of symptoms and heal the esophagus in 80-90% of patients. These drugs are also useful in treating strictures, one of the most serious complications of GERD. They are more effective than H2 blockers in reducing acid secretion. Several proton pump inhibitors are available in the United States. The FDA approved omeprazole (Prilosec) in 1989, lansoprazole (Prevacid) in 1995, rabeprazole (AcipHex) in 1999, pantoprazole (Pantoloc/Protonix) in 2000, and esomeprazole (Nexium) in 2001. Zegerid is a combination of omeprazole and sodium bicarbonate. Dexlansoprazole (Kapidex, renamed Dexilant in the US in 2010) received approval in 2009. Surgery

. Surgical treatment may be indicated in the following cases:

- the patient is not interested in long-term drug therapy;

- symptoms cannot be controlled by methods other than surgery;

- symptoms return despite treatment;

- serious complications develop.

When choosing surgical treatment, a thorough analysis of all circumstances with the participation of a gastroenterologist and surgeon is recommended.

How long do you need to take medication to keep GERD from getting out of control?

GERD is a chronic disease, and most patients require long-term therapy to keep its symptoms effectively controlled. Similar to how patients with high blood pressure or chronic headaches also require regular treatment. Even after symptoms are controlled, the underlying disease remains. It is possible that you will need to take medications for the rest of your life to control GERD. Unless new drugs and treatments are developed during this time.

Is taking long-term medications to treat GERD harmful?

Long-term use of any medication should only be done under the guidance of a physician. This applies to both prescription and over-the-counter medications. Side effects are rare, however, any drug can potentially have unwanted side effects. H2 blockers have been used to treat reflux disease since the mid-1970s. Since 1995, they have been available over the counter in reduced doses to treat rare heartburn. They have proven to be safe, although they sometimes cause side effects such as headaches and diarrhea. The proton pump inhibitors omeprazole and lansoprazole have been regularly used by patients with GERD for many years (omeprazole was approved in the US in 1989 and worldwide a few years after that). Side effects from these drugs are rare and mainly include occasional diarrhea, headache, or stomach upset. These side effects are generally no more common than with placebo and usually occur when starting to use the drug. If none of these side effects have appeared after months or years of taking proton pump inhibitors, they are unlikely to appear later. Patients with heart disease who are taking clopidogrel (Plavix) should avoid taking proton pump inhibitors such as omeprazole and esomeprazole. In addition, recent studies have shown that long-term use of PPIs, especially more than once daily, can cause osteoporosis, bone fractures, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, and hospital-acquired colitis. Patients should discuss this with their healthcare provider.

When is surgery an alternative to therapeutic treatment for GERD?

Drug therapy helps control symptoms as long as the medication is taken correctly. Surgery is an alternative usually when long-term treatment is either ineffective or undesirable, or when there are serious complications of GERD. The most common surgical procedure to treat GERD is a Nissen fundoplication. It can be performed laparoscopically by an experienced surgeon. The purpose of the operation is to increase pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter to prevent reflux. When performed by an experienced surgeon (who has performed at least 30–50 laparoscopic procedures), its success approaches that of well-planned and carefully executed therapeutic treatment with proton pump inhibitors. Side effects or complications associated with surgery occur in 5-20% of cases. The most common is dysphagia, or difficulty swallowing. It is usually temporary and goes away in 3–6 months. Another problem that occurs in some patients is their inability to burp or vomit. This is because the operation creates a physical barrier to any type of backflow of any stomach contents. A consequence of the inability to belch effectively is “gas-bloat” syndrome - bloating and discomfort in the abdomen. The surgically created anti-reflux barrier can “break” in much the same way as a hernia penetrates other parts of the body. The recurrence rate has not been determined but may be in the range of 10–30% within 20 years after surgery. Factors that may contribute to this “breakdown” include: weightlifting, strenuous exercise, sudden changes in weight, severe vomiting. Any of these factors can increase blood pressure, which can lead to weakening or disruption of the anti-reflux barrier created as a result of surgery. In some patients, even after surgery, symptoms of GERD may persist and medication will need to be continued.

Living with GERD

It is important to recognize that GERD is a disease that should not be ignored or self-medicated. Heartburn, the most common symptom, is so common that its importance is often underestimated. It may be overlooked and not associated with GERD. It is important to understand that GERD can have serious consequences. The complications that can arise, as well as the discomfort or pain from acid reflux, can affect all aspects of a person's daily life - emotional, social and professional. Studies that measure the emotional state of those with untreated GERD often report worse scores than those with other chronic diseases, such as diabetes, high blood pressure, peptic ulcers, or angina. However, almost half of those suffering from acid reflux do not recognize it as a disease. GERD is a disease. It is not a consequence of an incorrect lifestyle. It is usually accompanied by obvious symptoms, but can occur in the absence of them. Ignoring them or improperly treating them can lead to more serious complications. Most people with GERD have a mild form of the disease, which can be controlled with lifestyle changes and medications. If you suspect you have GERD, the first step is to see your doctor for an accurate diagnosis. Once recognized, GERD is usually treatable. By partnering with your doctor, you can develop the best treatment strategy available to you. ______________________________________________________________________________ The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases (IFFGD). IFFGD does not warrant or endorse any product in this publication or any claims made by the author and does not accept any liability regarding such matters. This brochure is in no way intended to replace medical advice. We recommend visiting a doctor if your health problem requires an expert opinion. The original (English) version of the brochure was written using an educational grant from Takeda.

__________________________________________________________________________ Illustrations added during translation. We also recommend that you read the materials “for patients”:

- British Society of Gastroenterology recommendations for patients with heartburn and gastroesophageal reflux.

- Advice from the American College of Gastroenterology. Is it just minor heartburn or something more serious?

- American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines. Heartburn and reflux disease. The essence of the problem.

Back to section

| Diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases | Symptoms of gastrointestinal diseases | Advice from doctors in the USA, Russia, etc. | Heartburn and GERD |