Quick transition Treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is the reflux of gastric contents (acid and enzymes such as pepsin) into the larynx, leading to hoarseness, a feeling of a lump in the throat, difficulty swallowing, coughing, and a feeling of mucus in the laryngopharynx.

Reflux as a cause of the above symptoms without gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is constantly being questioned. Guidelines issued by specialist societies in the field of laryngology and gastroenterology present different points of view. Both groups acknowledge that interpretation of existing studies is complicated by vague diagnostic criteria for LPR, variable treatment response rates, and large placebo effects in treatments.

There are relatively limited data on the prevalence of LPR: approximately 30% of healthy people may have episodes of reflux on 24-hour pH measurements or show characteristic changes in the larynx.

LPR can directly or indirectly cause laryngeal symptoms. The direct mechanism involves irritation of the mucous membrane of the larynx with caustic substances - refluxates (acid, pepsin). The indirect mechanism involves irritation of the esophagus, leading to laryngeal reflexes and symptoms.

Helicobacter pylori infection may also contribute. The prevalence of H. pylori among patients with LPR is about 44%.

Laryngophangeal reflux and GERD

Although stomach acid is common to both LPR and GERD, many differences exist, making LPR a distinct clinical entity.

- A prerequisite for GERD is heartburn, which is reliably observed only in 40% of patients with LPR.

- Most patients with GERD have evidence of esophagitis on biopsy, while patients with LPR have evidence of esophagitis in only 25% of cases.

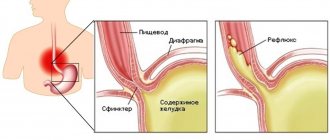

- GERD is thought to be a problem of the lower esophageal sphincter and occurs primarily when lying down. In contrast, LPR is seen primarily as a problem of the upper esophageal sphincter, and occurs primarily in an upright position during exercise.

- To form LPR, much less acid exposure is required than with GERD.

There are significant differences between the mucous membrane of the esophagus and larynx.

- The upper limit of normal for acid reflux into the esophagus is considered to be up to 50 episodes per day, while 4 episodes of reflux into the larynx is no longer considered normal.

- In the larynx, unlike the esophagus, which eliminates acid through peristalsis, refluxate persists much longer, causing additional irritation.

- The epithelium of the larynx is thin and poorly adapted to combat caustic chemical damage from the same pepsin and acid.

Treatment of patients with dysphonia in gastroesophageal reflux disease

Among the important problems of otorhinolaryngology, one of the main places is occupied by reducing the incidence of people in vocal professions and their return to full-time work. Diseases of the vocal apparatus not only entail a significant increase in days of incapacity for work, but also often lead to the professional unsuitability of patients.

Comprehensive studies of the etiology, pathogenesis and clinic of voice disorders conducted recently have made some adjustments and enriched our understanding of the nature of these diseases. Voice disorders began to be considered not as a local lesion, but as a disease of the body involving many organs and systems in the process.

The results of modern epidemiological studies indicate a significant prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) throughout the world. Over the past decades, GERD has been consistently diagnosed in 40% of the adult population, and this figure does not tend to decrease [10].

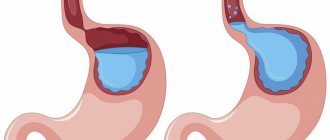

Most scientists consider GERD as an acid-dependent disease that occurs against the background of a primary disorder of the motor function of the upper digestive tract and is manifested by a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, a slowdown in esophageal clearance, a weakening of the propulsive activity of the stomach, and the pathological effects of refluxate [1].

According to the WHO classification, GERD is a chronic recurrent disease caused by a violation of the motor-evacuation function of the gastroesophageal zone, characterized by spontaneous or regularly repeated reflux of gastric or duodenal contents into the esophagus, which leads to damage to the esophagus with the development of erosive-ulcerative, catarrhal or functional disorders. [5].

The clinical manifestations of GERD, its course and prognosis depend on the duration of contact of the refluxate with the mucous membrane of the esophagus. An important role is played directly by the composition of the contents entering the esophagus. In 20% of cases, refluxate has an alkaline reaction, which is associated with duodenogastric reflux. In these cases, the adverse effects of bile acids and pancreatic enzymes on the mucous membrane of the esophagus, leading to the destruction of the natural mucin barrier, are of pathogenetic significance. The leading role in the pathogenesis of the development of GERD is ultimately assigned not to the absolute levels of aggressive components of the gastric and duodenal contents, but to the disruption of the motor-evacuation function of the gastroesophageal zone [7].

Symptoms characteristic of GERD are: heartburn, belching, chest pain, hiccups, vomiting, a feeling of early satiety, flatulence. In clinical practice, GERD can manifest as both typical and extraesophageal symptoms, and this pathology is not only masked by various extraesophageal complaints, but also provokes the development of a number of diseases [4].

Numerous studies have confirmed the development of bronchial asthma in patients suffering from GERD. At night, pathological gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is considered a trigger for asthma attacks. A decrease in the frequency of swallowing movements during sleep aggravates the effect of refluxate, which causes the development of bronchospasm both due to microaspiration and due to the activation of neuroreflex mechanisms. A large population-based cohort study, begun in 1971 and involving 8513 patients, is indicative in this regard. With this observation, it was reliably proven that in patients with an initial diagnosis of GERD, various bronchopulmonary manifestations were noted over a period of 20 years, including “reflux-induced bronchial asthma” [8, 11].

Pathological changes in the oral cavity with GERD also cannot be classified as rare. Damage to the oral cavity in patients with GERD depends on the degree of acidification of the salivary fluid. In these cases, saliva begins to have a damaging effect on the mucous membrane and hard tissues of the teeth (stomatitis, erosion of tooth enamel, caries, periodontitis) [2].

In some cases, pathological reflux provokes a reflex development of an attack of angina and arrhythmia. The occurrence of chest pain during physical activity and its combination with heartburn indicates a combined pathology [3].

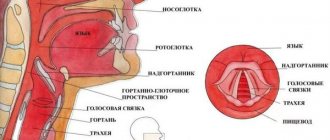

In otorhinolaryngology, reflux-induced pathology, according to various authors, may include the following diseases and syndromes: chronic pharyngitis, chronic otitis media, chronic sinusitis, rhonchopathy, chronic laryngitis, benign neoplasms of the larynx, laryngospasm and the feeling of a “lump” in the throat [6, 9].

The close topographic relationship between the upper anatomical narrowing of the esophagus and the laryngopharynx determines the participation of the pathology of the proximal digestive tract in the pathogenesis of some voice disorders, since the epithelium of the pharynx and larynx is more sensitive to the damaging effects of refluxate and is less protected compared to the esophagus.

Most patients suffering from GERD and turning to a phoniatrist do not have pathogmonic complaints. There is no heartburn, belching, chest pain, or hiccups. This is due to the presence of another form of the disease, which has received the somewhat incorrect name “pharyngolaryngeal reflux (PLR),” which is caused by gastrointestinal contents penetrating into the hypopharynx through the upper esophageal sphincter. When performing rigid endolaryngoscopy and microlaryngoscopy, LLR manifests itself in the form of edema, infiltration and hyperemia of the mucous membrane of the interarytenoid region.

In Fig. Figure 1 shows an endophotograph of a patient with posterior laryngitis caused by LPR. Changes in the interarytenoid region and practically intact vocal folds are clearly visible.

This work is devoted to the analysis of our own observations on the study of clinical characteristics and treatment of patients with voice disorders with GERD in an ENT clinic.

This article analyzes data from the examination and treatment of 983 patients aged 18 to 67 years suffering from various voice disorders for the period from December 2007 to December 2009.

To diagnose a patient with a voice disorder, we used the following methods for examining the larynx: microlaryngoscopy and videolaryngoscopy. Videoendoscopy with photo documentation and archiving was carried out using a 70° rigid endolaryngeal endoscope and appropriate equipment. Videoendoscopy and mirolaryngoscopy were performed both during the consultation and to monitor the quality of the treatment provided.

All patients under our supervision were distributed according to nosological forms as follows: chronic hyperplastic laryngitis (230), Reinke-Hajek polypoid edema of the vocal folds (210), vocal fold polyps (70), vocal fold nodules (120), vocal fold cysts ( 18), contact granulomas (64), functional voice disorders (78), subatrophic laryngitis with vocal groove (12), paresis and paralysis of the larynx (56), laryngeal papillomatosis (82), posterior laryngitis (43).

All patients with chronic hyperplastic laryngitis (simple infiltrative form, diffuse infiltrative form with foci of flat keratosis, diffuse papillary or focal keratosis with the presence of hyperplasia in the form of granulomas and polypoid thickenings) were diagnosed with signs of LPR in the interarytenoid region.

Changes in the mucous membrane of the interarytenoid region with GERD and constant vocal stress also lead to the development of contact granulomas of the larynx. All our patients with this pathology showed signs of posterior laryngitis (Fig. 2). The identified gray-red mushroom-shaped formation in the area of the vocal process of the arytenoid cartilage in the vast majority of our patients was located on the side corresponding to the “habitual posture” of sleep, which once again indicates the pathogenic role of the “acid track” in the development of the disease.

Functional diseases of the larynx are a syndrome-like pathology with posterior laryngitis caused by LPR. This category of patients, as well as with functional voice disorders, are bothered by a feeling of a “lump” in the throat, hoarseness, which increases with speech or vocal stress. During laryngoscopic examination, due to infiltration and swelling of the mucous membrane in the interarytenoid region during phonation, the vocal folds do not close, and an insufficiently experienced specialist often regards this voice pathology as phononeurosis.

Thus, in all patients with chronic hyperplastic laryngitis and contact granulomas of the vocal folds, changes were noted in the interarytenoid region, which not only indicates the participation of GERD in the pathogenesis of this pathology, but also determines the persistent long course of the disease with resistance to all types of medications, as well as surgical treatment.

Posterior laryngitis is a purely extrapharyngeal manifestation of GERD, and knowledge of the clinical features of the above-described pathology allows not only to diagnose the disease in a short time, but also to prescribe appropriate examination and treatment in a timely manner.

The comprehensive treatment program for voice disorders included drug therapy, endolaryngeal microsurgery, coblation surgery, phonopedia and physiotherapy. The choice of therapeutic interventions and their combination were carried out in a differentiated manner, taking into account the stage of the disease, etiopathogenetic and clinical characteristics, as well as the personal characteristics of the patient.

In the ENT clinic, as part of our complex treatment method and as the initial stage of treatment for GERD, drugs that affect gastrointestinal motility (prokinetics) were used. The prescription of prokinetics was made taking into account the fact that the key etiological factor in the development of GERD, according to the WHO classification, is a violation of the motor-evacuation function of the gastroesophageal zone.

Ganaton is a new drug for restoring tone and improving coordination in the digestive system, which we have been using for two years. The active substance of Ganaton is itopride. When taken orally, Ganaton causes blockade of D2-dopamine receptors, inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, increases the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, improves the evacuation of gastric contents, normalizes intragastric pressure and prevents reflux of contents into the laryngopharynx. The use of itopride is preferable due to the minimal spectrum of side effects in the therapeutic dose range (50 mg, three times a day), which distinguishes it from previously used prokinetics, and the treatment of functional disorders of the gastroduodenal zone should be long-term, at least a month. Safety and high efficacy have been confirmed by numerous multicenter studies [12].

In accordance with the biological effect of Ganaton, the drug was prescribed to all patients with voice disorder and clinical manifestations of GERD in the larynx (571 patients out of 983) 50 mg 3 times a day before meals for 4 weeks. In the future, for specialized diagnosis and prevention, the patient was strongly recommended to consult a gastroenterologist.

In Fig. 3 and fig. Figure 4 clearly shows the dynamics of drug relief of the inflammatory process in the larynx and interarytenoid region in a patient with exacerbation of chronic hyperplastic laryngitis against the background of GERD. In complex therapy, Ganaton was used according to the generally accepted scheme.

Analyzing the data presented, it can be noted that in patients with chronic inflammatory pathology of the larynx, gastroesophageal reflux is not only one of the reasons for the development of the disease, but also determines its long-term, persistent course.

The use of Ganaton in the complex treatment of all types of voice disorders due to GERD and LPR is pathogenetically justified. The drug allows you to eliminate inflammation in the interarytenoid region in a fairly short time and prevent relapses.

Literature

- Babak O. Ya., Fadeenko G. D. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. K.: JV ZAO Interpharma-Kyiv, 2000.

- Barer G.M., Maev I.V., Busarova G.A. et al. Manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the oral cavity // Cathedra. 2004; 9:58–61.

- Ivashkin V.T., Trukhmanov A.S. Programmatic treatment of gastroesophageal disease in the daily practice of a doctor // Ros. magazine gastroenterol., hepatol., coloproctol. 2003. No. 6, p. 18–26.

- Prevention and treatment of chronic diseases of the upper gastrointestinal tract. Ed. acad. RAMS V. T. Ivashkina. M., 2002.

- Maev I.V., Yurenev G.L. Bronchopulmonary and oropharyngeal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease //

- Gastroenterology. 2006, vol. 8, no. 2.

- Soldatsky Yu. L. Otorhinolaryngological manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease // Diseases of the digestive organs. 2007, vol. 9, no. 2, p. 42–47.

- Trukhmanov A. S., Maev I. V. Non-erosive reflux disease from the perspective of modern gastroenterology: clinical features and impact on the quality of life of patients // GRM. 2004, No. 23, p. 1344–1348.

- Chang AB, Lasserson TJ et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of gastro-oesophageal reflux interventions for chronic cough associated with gastro-oesophageal reflux // BMJ. 2006. Vol. 332, no. 1, p. 11–17.

- Koufman JA The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) // Laryngoscope. 1991. Vol. 101, No. 4. Pt2 (Suppl. 53), 78 p.

- Nandurkar S., Talleu NJ Epidemiology and natural history of reflux disease // Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2000, no. 5, p. 743–757.

- Sontag SJ Gastroesophageal reflux and asthma // Am J Med. 1997. Vol. 103, No. 5 A, p. 84–90.

- Qi Zhu Recent Data of Itopride in the Treatment of Functional Dyspepsia in Chinese Patients; Ganaton Regional Advisory Board Meeting Thailand 2010; 3:1–8.

E. V. Demchenko , Candidate of Medical Sciences G. F. Ivanchenko , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor E. A. Kochesokova E. P. Oleinik

LLC "ENT Clinic of Professor G. F. Ivanchenko" , Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux

- Dysphonia or hoarseness;

- cough;

- feeling of a lump in the throat;

- discomfort and feeling of mucus in the throat;

- dysphagia (impaired swallowing).

Some researchers believe that chronic irritation of the larynx may lead to the development of carcinoma in patients who do not drink alcohol or smoke, although there is no data to support this.

Symptoms characteristic of LPR may also be caused by the following conditions:

- postnasal drip;

- allergic rhinitis;

- vasomotor rhinitis;

- upper respiratory tract infections;

- habitual coughing;

- use of tobacco or alcohol;

- excessive use of voice;

- changes in temperature or climate;

- emotional problems;

- environmental irritants;

- vagal neuropathy.

Diagnostics

There is considerable controversy regarding the appropriate way to diagnose LPR.

Most patients are diagnosed clinically, based on symptoms associated with LPR.

During laryngoscopy (examination of the larynx), swelling and hyperemia (redness) of varying degrees are noted. However, the relatively weak correlation between symptoms and endoscopic findings argues against the use of endoscopic diagnostic methods.

The Reflux Symptom Score and Reflux Symptom Index are well suited for both diagnosis and monitoring response to therapy.

Daily Ph-metry with a dual sensor probe, despite its excellent sensitivity and specificity, is questioned, since the results of this diagnostic method often do not correlate with the severity of symptoms.

Another diagnostic option may be empirical PPI therapy.

Ganaton

The main purpose of the drug ganaton (itopride) is to stimulate the tone and motility of the digestive tract. The drug is used for the symptomatic correction of signs of chronic gastritis (relief of discomfort, bloating and abdominal pain, relief from nausea, vomiting and anorexia).

Today, diseases manifested by disorders of gastrointestinal motility are much more common than half a century ago. In this regard, the introduction into practice of new and improvement of already used medicines that can properly improve the functioning of the esophagus, stomach and intestines is a task of increased importance. The drug ganaton is successfully used for two main pathological conditions of the digestive tract: GERD (this scary abbreviation stands for gastroesophageal reflux disease) and functional dyspepsia. GERD develops as a result of the backflow of stomach contents into the esophagus. This is a chronic disease that periodically worsens, but each subsequent time its symptoms become more pronounced. GERD is manifested by heartburn, sour or bitter belching, regurgitation of food, and difficulty swallowing. The greatest damage from GERD occurs in the esophagus, which is damaged by the aggressively acidic contents of the stomach. As for functional dyspepsia, it consists of a group of symptoms that persist for several months, including burning and pain in the epigastric region (“in the pit of the stomach”), a feeling of fullness in the stomach, and premature satiety. The pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia is based on impaired motility of the stomach and duodenum, functional weakness of the antrum (opening into the duodenum) of the stomach and general antroduodenal uncoordination.

The “gold standard” in the treatment of these and etiologically related diseases and pathological conditions are prokinetics, to which Ganaton has the honor to belong. This is a new prokinetic agent that is advisable to prescribe in the initial stages of gastrointestinal diseases. The name itself is “ganatone”, and this is an abbreviation for the English “gastric natural tone”, i.e. “restoring normal gastric tone” quite eloquently indicates its main purpose. The drug has a dual mechanism of action. Firstly, it suppresses the enzyme acetylcholinesterase while simultaneously increasing the motility of the digestive tract, and secondly, it takes an extremely radical position on dopamine D2 receptors, which also causes stimulation of gastrointestinal motility. Ganaton makes the process of gastric emptying faster, reducing the transit time of the bolus of food through the small intestine. The drug also has an antiemetic effect, which is associated with blocking the D2 chemoreceptors of the trigger zone of the vomiting center of the medulla oblongata.

Despite its relative “youth”, the drug ganaton has already gained strong authority, incl. and in Russia. Thus, a comparative study of ganaton and the drug domperidone, which has long been used for GERD and functional dyspepsia, was conducted at the Volgograd State Medical University. At the same time, ganaton showed the best results, additionally demonstrating such advantages over its rival as the absence of extrapyramidal side reactions, minimal interaction with other drugs, and metabolism in the absence of cytochrome P-450.

Ganaton is available in tablets. The dosage regimen and frequency of administration of the drug are as follows: 50 mg 3 times a day, with the possibility of reducing the dose taking into account the patient’s age.

Treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux

Lifestyle changes and diet are the main approach in the treatment of LPR and GERD. The role of drug therapy is more controversial. It is unknown whether asymptomatic patients with incidentally detected signs of LPR require treatment. There are theoretical concerns that LPR may increase the risk of malignancy, but this has not yet been proven. In any case, patients with asymptomatic LPR are advised to follow a diet.

Patients are advised to quit smoking, alcohol, and avoid foods and drinks containing caffeine, chocolate, and mint. Prohibited foods also include most fruits (especially citrus fruits), tomatoes, jams and jellies, barbecue sauces and most salad dressings, and spicy foods. Small meals are recommended.

You should avoid exercise for at least two hours after eating, and refrain from eating or drinking three hours before bedtime.

Drug therapy usually includes proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), H2 blockers, and antacids. A PPI is recommended for six months for most patients with LPR. This figure is based on the results of endoscopic studies (this is the time needed to reduce laryngeal edema), as well as the high percentage of relapse in the case of a three-month course of therapy. Discontinuation of therapy should be carried out gradually.

If therapy with PPIs and H2 blockers is unsuccessful, treatment with tricyclic antidepressants, gabapentin and pregabalin should be considered, since one of the possible mechanisms for the development of reflux is increased sensitivity of the larynx.