HomeChildren's clinicGastroenterologyIrritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a functional intestinal disorder in which there is no significant laboratory or instrumental evidence of the disease, although the patient sometimes feels very severe discomfort. In total, about 15-20% of the population suffers from this disease, most often at the age of 20-45 years. However, symptoms of IBS can also occur in children, especially teenagers.

Irritable bowel syndrome does not belong to the group of dangerous diseases, but without adequate treatment, this disorder significantly reduces the child’s quality of life. It should be remembered that a number of dangerous diseases of the intestines and other internal organs can manifest themselves with exactly the same symptoms as IBS. For this reason, this diagnosis can only be established after consulting a doctor and a full examination.

Introduction

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is one of the most common forms of functional digestive disorders (FDOD) not only in adults, but also in children and adolescents.

The prevalence of IBS varies between 10–15% [1, 2]. It is believed that IBS is more typical for young and middle-aged people; among patients, people under 50 years predominate [2, 3]. The incidence of IBS also increases during adolescence, in which the incidence reaches 35%. In children under 6 years of age with FROP accompanied by abdominal pain, IBS is diagnosed in a quarter of cases, and, as a rule, in this age group it develops as a result of acute intestinal infections (AIE) [4, 5]. All forms of IBS have a significant impact on the quality of life and cause anxiety in patients, which in turn reduces the effectiveness of treatment. All this emphasizes the clinical and social significance of this disease [6–8].

IBS: classification, etiology and pathogenesis

According to the definition of the Rome IV criteria and the Russian recommendations in children, IBS is defined as a symptom complex manifested by abnormal frequency of stool (4 or more times a day or 2 or less times a week), a violation of its shape and consistency, a change in the act of defecation in the form of additional effort or urgency urge with mucus in the stool and bloating [1, 9]. Mandatory conditions for the diagnosis of IBS are the relationship of symptoms, primarily abdominal pain, with the act of defecation: improvement after defecation, the connection of pain with changes in the frequency or consistency of stool [9]. Today, the biopsychosocial model of IBS development is generally accepted, according to which the key role in the formation of pathology belongs to the interaction of two main groups of pathogenetic mechanisms: psychosocial and sensorimotor. In other words, IBS is based on a violation of the neurohumoral regulation of the brain-gut axis, associated with the psycho-emotional sphere, autonomic disorders and increased visceral sensitivity [10, 11]. Recently, these key positions have been supplemented, according to new data, by the so-called “peripheral” mechanisms of IBS development: nonspecific inflammation, changes in the expression of tight junction proteins, increased permeability of the intestinal epithelium [12].

O.V. Gaus et al. [13] indicate a special role of the enteric nervous system (ENS) in the regulation of intestinal functions. The main channel of communication between the ENS and the brain is the vagus nerve. All links of the reflex pathways of the ENS begin and end at the intestinal level, which underlies the formation of unique “memory mechanisms” and contributes to the chronicity of IBS.

The cause of pain in patients with IBS is the so-called phenomenon of visceral hypersensitivity [13]. The possible trigger role of cognitive-behavioral disorders in the formation of IBS is indicated by MJ Spence et al. [14]: high levels of anxiety, negative perception of the disease, depression, and hypochondria increase the risk of developing IBS after an intestinal infection.

According to the current classification, variants of IBS are distinguished according to the predominance of clinical signs:

with constipation;

with diarrhea;

nonspecific, or mixed, option.

According to etiological mechanisms, the following variants of IBS are distinguished:

classic, stress-induced;

related to food intolerance, food induced;

post-infectious, associated with previous acute intestinal infection (PI-IBS).

It is believed that from 3% to 33% of patients who have had infectious gastroenteritis subsequently report symptoms of PI-IBS [15]. PI-IBS was first described by GT Stewart [16] in 1950 based on observations of patients who had suffered from dysentery. PI-IBS develops in 4–32% of patients after bacterial gastroenteritis caused by bacteria of the genera Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia

[17]. It has now been proven that not only acute bacterial gastroenterocolitis is a serious risk factor for the development of PI-IBS, but also viral infections [13]. For example, PI-IBS in children who have had rotavirus infection develops in 24.6% of cases [18]. A.A. Belova et al. [19] reported that giardiasis increases the risk of developing PI-IBS by influencing the species composition and diversity of the intestinal microbiota, host metabolism, immune response, mucosal barrier and gastrointestinal (GI) motility.

A number of factors, such as young age, female gender, duration of diarrhea, severity of ACI, may increase the risk of developing PI-IBS [20–23]. M. Thabane et al. [23] found that the risk of developing PI-IBS after ACI increases 6 times, with risk factors including young age, prolonged fever, anxiety and depression. The risk of developing PI-IBS increases at least 2-fold if diarrhea lasts more than 1 week. and more than 3 times with a duration of diarrhea of more than 3 weeks. In addition, the incidence of IBS development is influenced by the severity of the local inflammatory process, increasing the risk of developing PI-IBS in the presence of hemocolitis [20, 22].

PI-IBS develops as a result of the immune system reacting to an infectious agent with a subsequent weakening of the immune response. Patients experience mild inflammation of the colon and increased intestinal permeability, which is confirmed by an increase in the level of cytokines (interleukins 4, 6, 10, tumor necrosis factor-α) [18]. A connection has been identified between the development of PI-IBS and a single nucleotide substitution in the promoter of the CDH1

[17]. According to KA Gwee et al. [24], in a study of biopsies of the colon mucosa in patients with PI-IBS, an increase in the number of enterochrome-affinity cells, mast cells and T-lymphocytes in the lamina propria of the mucosa was recorded. It has been established that inflammation of the intestinal mucosa in acute intestinal infections leads to increased visceral sensitivity [25].

Results of modern concepts and surveys

Now a new pathogenetic scheme has appeared in the form:

- intestines;

- microbiota;

- brain

As a result of consistent therapeutic effects on all these three links, there was a reassessment of the mechanisms (including triggers) that contribute to the development of IBS, especially such a symptom as visceral hypersensitivity.

It is considered to be the main pathogenetic factor in the appearance of irritable bowel syndrome in childhood. Thanks to modern research methods, healthcare professionals now have new insights into the nature and function of the gut microbiome. The role of microbiota in the pathogenetic mechanisms of digestive disorders is also assessed differently.

It is known that probiotics have been used for medicinal purposes for a long time, and now there are excellent opportunities to select the type that will help in solving a specific clinical problem. Since the intestinal microbiota and all the active substances contained in it actively interact with food components and vitamins, this causes at least two effects:

- anti-inflammatory;

- immune.

Both of them are aimed at strengthening the intestinal barrier. As for the use of complex action products with the probiotic strain L.reuteri DSM 17938, its clinical effect has been proven in practice, including a beneficial effect on the immune system and intestinal epithelium. This is how it is possible to increase the level of effectiveness of treatment of irritable bowel syndrome in young patients.

The role of the microbiome in the pathogenesis of PI-IBS

The role of the microbiome in the development of PI-IBS has also been proven. Disruption of the microbial ecosystem can lead to shifts in bile acids, cytokines, and the immune environment, which can affect epithelial and neuromuscular function and cause further disruption of the microbiome. In PI-IBS, a decrease in the number of bacteria belonging to the genus Bacteroidetes

, while in other variants of IBS the

Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes

[15, 26].

Subdoligranulum

, responsible for the synthesis of interleukin 1β, was found in patients with PI-IBS This indicates a specific activity of the immune system against commensal microbes during pathological conditions and suggests a complex and bidirectional interaction between the microbiota and the immune response that occurs in PI-IBS.

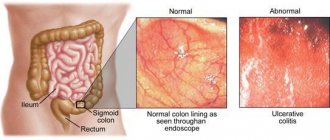

Diagnosis and treatment of IBS

Currently, attempts are being made to systematize recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of PI-IBS, while specific treatment recommendations for PI-IBS have not been developed, which often complicates the diagnosis of this form of IBS and leads to a later start of therapy. Until recently, it was believed that the diagnosis of PI-IBS could be made after a comprehensive examination (endoscopic examination methods, CT colonography), which made it possible to exclude organic gastrointestinal diseases in the patient [17], but recently a number of works have been published [1, 9, 10 , 28], who demonstrated that additional instrumental studies do not have significant diagnostic value in the majority of IBS patients without anxiety symptoms.

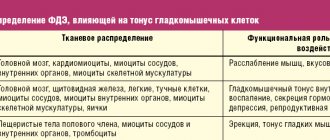

Treatment of PI-IBS is usually symptomatic and includes dietary advice, antispasmodics, probiotics, intestinal antiseptics, antidiarrheals or laxatives depending on the predominant symptoms. Treatment may include psychotherapy and antidepressants [1, 9, 28]. In the treatment of PI-IBS, it is important not only to relieve the abdominal syndrome, but also to influence the main links in the pathogenesis, since the relief of abdominal syndrome affects the quality of life and the severity of anxiety in the patient, and pathogenetic therapy affects the quality of life and the objective status of the patient. One of the universal drugs is trimebutin (Neobutin®). In addition to the ability to modulate visceral hypersensitivity and modify the subjective perception of pain, trimebutine has a nonspecific affinity for peripheral δ-, μ- and κ-receptors, without showing selectivity for any of them, due to which it can both enhance and inhibit gastrointestinal motility depending on the previous receptor tuning [29].

Since PI-IBS is a condition with a clear infectious trigger that leads to disruption of the normal microflora, an important point in the treatment of PI-IBS is the impact on the microbiota-gut-brain axis by including probiotics and synbiotics in treatment regimens. Today, according to the Rome IV criteria, probiotics are included in treatment regimens for IBS. With combination therapy using a probiotic and trimebutine for IBS, improvement was achieved in 81.8% of patients [30].

The effectiveness of probiotic therapy depends on the compliance of the strains used with certain requirements: they must be phenotypically and genotypically identifiable, acid-resistant and safe. A representative of such synbiotics is Maxilac®. Thanks to the use of innovative production technology - MURE (Multi Resistant Encapsulation), the bacteria present in the Maxilac® synbiotic are protected from the acidic contents of gastric juice, bile salts and digestive enzymes. This protection allows them to adapt and take root in the intestinal lumen, maintaining high biological activity.

Causes

The work of the intestines is regulated by the autonomic nervous system, which is “controlled” from the brain. Overexcitation of the midline structures of the brain triggers a whole cascade of reactions of the nervous system, leading to disruption of the innervation (conduction of nerve impulses) of the intestinal wall, disruption of muscle tone of the large and small intestines. As a result, some parts of the intestine spasm, while others, on the contrary, relax, which causes the main symptoms of IBS. What can cause overexcitation of the nervous system? Here are the most common reasons:

- Chronic stress.

- Fatigue, asthenic syndrome.

- Depression.

- Anxiety disorders: phobias, panic attacks, obsessions.

- Neuroses.

- PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder).

- Personality disorders (psychopathy).

- Organic mental disorders.

- Alcoholism, drug addiction, substance abuse, smoking.

- Schizophrenia spectrum disorders.

Clinical observation of PI-IBS

Patient M., 9 years old, was admitted with complaints of abdominal pain, mainly in the morning, accompanied by frequent loose stools with mucus up to 3-4 times a day. The pain syndrome weakened or stopped after bowel movements. The above complaints were observed for 7 months. From the anamnesis it is known that 8 months. ago, the child suffered acute infectious gastroenterocolitis of severe Salmonella etiology, for which he received antibacterial therapy (ceftriaxone) and intestinal antiseptics (nifuroxazide). He was discharged home with minimal dyspeptic symptoms and unformed stools. After 2 weeks Abdominal pain appeared, mainly in the morning, relieved after defecation, mushy stool with mucus. After another 7 days, the frequency of stool increased to 3 times a day. We treated ourselves using pancreatin preparations and antispasmodics, without effect. After 1 month We contacted our local pediatrician. When examined according to the results of a clinical blood test, no anemia or inflammatory changes were detected; in the coprogram there is type 2 steatorrhea, a large amount of iodophilic flora, mucus. A smear for the dysentery group and salmonellosis showed a negative result three times. Enterosorbents, repeated courses of nitrofurans and antispasmodics were prescribed. During treatment, the intensity of the pain syndrome decreased, but pain occurred several times a week, mainly in the morning, semi-formed stools, type 4–5 on the Bristol scale, 1–2 times a day. After a course of treatment, the pediatrician recommended limiting the amount of consumption of foods containing dietary fiber; against this background, pain that relieved after defecation bothered the child 1–2 times a week. After 1 month after treatment, at the stage of expanding the diet, abdominal pain again became more frequent, accompanied by the passage of pasty stools with mucus. For a month we treated ourselves on our own, taking enterosorbents and enzyme preparations with a short-term positive effect.

Considering the persistent complaints, the child was sent for examination to the central district hospital at his place of residence. During the examination, clinical and biochemical blood tests were within normal limits; ultrasound of the abdominal organs revealed no pathological changes. During microbiological examination of stool, opportunistic flora was sown. In the hospital, antibacterial drugs (4th generation cephalosporins), enterosorbents, enzymes, and antispasmodics were prescribed. During treatment, the dynamics are positive, the pain syndrome is relieved, stools are 1–2 times a day, semi-formed (type 4–5 on the Bristol scale). After 2 weeks After treatment, the child’s mother noted the appearance of pain and increased bowel movements when consuming dairy products. Milk was excluded, but the pain syndrome persisted. After some time, bowel movements became more frequent again, up to 3 times a day. During the examination, an increase in the level of calprotectin to 180 μg/l was noted. The child was referred for consultation to a gastroenterologist. During the examination, it was noted that the child was suspicious, with expressed concern about his health, and showed particular anxiety about forced absences from school due to health problems. The child's mother is whiny and overly emotional. When collecting an anamnesis, it was established that the child had previously been treated for giardiasis, after which rare abdominal pain was noted, which self-limited without treatment. Over the past 4 months. The child's weight decreased by 2 kg.

Considering the presence of “alarm symptoms”—weight loss, blood in the stool, increased fecal calprotectin—an inpatient examination with colonoscopy was prescribed. According to a clinical blood test: leukocytes 4.88×109/l (eosinophils 1%, band 4%, segmented 65%, monocytes 3%, lymphocytes 27%), erythrocytes 4.48×1012/l, hemoglobin 139 g/l , platelets 286×109/l, ESR 5 mm/h. According to the coprogram: the consistency of the stool is soft, the color is brown, the reaction is sour, hidden blood is negative (negative), muscle fibers without striations are positive (positive), with striations negative, connective tissue is negative, fat is neutral, fatty acids are negative ., plant fiber negative, starch negative, intracellular negative, extracellular negative, leukocytes negative, erythrocytes negative, helminth eggs negative, yeast fungi positive.

A hydrogen breath test with lactulose was performed and high bacterial contamination of the small intestine was revealed. When analyzing stool for opportunistic flora, Escherichia coli

(lactose-negative) 109 CFU/g,

Enterobacter cloacae

1.4×108 CFU/g

, Proteus mirabilis

2×107 CFU/g. Colonoscopy revealed erythematous proctosigmoiditis and terminal ileitis. A morphological examination of a biopsy of the small intestine revealed signs of diffuse, mild lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lamina propria. A biopsy of the transverse colon mucosa revealed edema and diffuse polymorphic cell infiltration. According to a biopsy of material from the mucous membrane of the descending colon: edema, focal polymorphocellular inflammatory infiltration, mucus. When performing a biopsy of material from the mucous membrane of the sigmoid colon, moderate edema and polymorphocellular inflammatory infiltration were noted; biopsies of material from the rectum: focal and polymorphocellular inflammatory infiltration. Taking into account the main symptoms of PI-IBS, a course of therapy with trimebutine, dioctahedral smectite, as well as the multi-strain synbiotic Maxilac®, and psychotropic drugs was prescribed. After 1 month From the start of treatment, the patient showed a significant improvement: stool no more than 1-2 times in the morning after breakfast. At the same time, symptoms of depression and anxiety persisted. The patient was given a recommendation to take trimebutine as needed for abdominal pain, and was prescribed a repeat course of the synbiotic and sedatives. After 3 months At the next visit to the gastroenterologist, the patient had no complaints, and body weight restoration was noted. The boy was actively involved in sports.

Symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome has the following symptoms:

- Severe abdominal pain and cramps that may stop after the bowels have been completely emptied;

- Diarrhea or constipation;

- Bloating and increased gas formation;

- Frequent and sudden urge to go to the toilet;

- A feeling that the bowels are full or not completely emptied, even if this is not the case;

- Discharge of mucus from the anus.

With this disease, all of the above symptoms, or some of them, may be present. Usually their manifestation is not constant, but is paroxysmal in nature. In most cases, an exacerbation can last up to four days. During the break between them, there are practically no unpleasant sensations or they are minimized. The break between exacerbations can be both long and short.

Since the presence of this disease is associated with many unpleasant sensations that can reduce the quality of life and create discomfort in the most ordinary life situations. Therefore, many patients become overly nervous and irritable. And some of them may be diagnosed with symptoms of depression. But all this does not indicate the presence of mental illness or psychological problems.

In addition, signs of irritable bowel syndrome can often be mistaken for manifestations of many other diseases. And many people, when unwell for a short time, even try to postpone a visit to a specialist, limiting themselves to independent methods of treatment. Such self-medication in most cases does not give the expected result, and sometimes can even significantly worsen the patient’s well-being.