Eventration

Medical tactics depend on the etiology and severity of the prolapse. In case of traumatic pathology, suturing of the wound with a thorough revision of the abdominal cavity, antibacterial and antiseptic treatment, resection of the prolapsed omentum and damaged areas of the intestine is recommended. Victims with internal eventration urgently undergo thoracolaparotomy with reduction or resection of the affected abdominal organs and suturing of the diaphragmatic wound. Surgical correction of congenital forms of the disease is carried out within 3-4 hours after the birth of the child.

In case of incomplete postlaparotomy eventration, conservative therapy is acceptable: the patient is placed on bed rest, intestinal function is regulated, antibiotics and infusion therapy are prescribed. In case of I degree of prolapse, a tight bandage is applied; in case of II degree, the wound is additionally sanitized. Reconstructive plastic surgery with subcutaneous eventration is performed after 2-3 months. Secondary sutures to eliminate tissue defects in case of partial prolapse of organs are applied on days 6-8. In case of complete and true eventration, the intervention (elimination of eventration) is performed urgently, taking into account the presence or absence of purulent-inflammatory processes in the postoperative wound and abdominal cavity:

- During aseptic eventration

. Irrigation of prolapsed organs with antibacterial drugs with layer-by-layer blind suturing of the abdominal wall through all layers with special surgical sutures is indicated. To reduce tension and prevent teething, unloading fixation is used using buttons, gauze, or rubber tubes. - When eventrating into a purulent wound

. It is recommended to clean the wound from pus, wash it with an antiseptic solution, and plastic surgery using unloading rubber tubes. In the absence of intestinal paresis and peritonitis, ointment tamponade of the wound, application of an aseptic dressing and plaster splint, and suturing of the defect after epithelialization are possible. - In case of recurrent eventration

. Allograft placement is most effective. Taking into account the immunological activity of materials, synthetic explants and the use of dura mater are preferred. A similar approach is used when tensioning the edges of the wound or a significant postoperative defect in the abdominal wall.

In the postoperative period, wound care is carried out; antibiotics, immunostimulants, and vitamin therapy are prescribed to improve regenerative processes. Prevention of intestinal obstruction and peritonitis, detoxification and anti-shock therapy with the introduction of colloid and crystalloid solutions to correct metabolic disorders are carried out.

Stories of a Surgeon: Eventration

In surgery there is such a thing as eventration. It is understood as a suddenly developed defect in the abdominal wall, as a result of which conditions are created for the depressurization of the abdominal cavity and the release of the insides out or under the skin. For example, in action films they often show how, after a slash with a sword or katana in the stomach, a person’s internal organs fall out. This is eventration. But in real life, most often this condition occurs due to the failure of the edges of a postoperative wound or scar. Why is it developing? There are several groups of factors:

- The reason may be in the operating technique. Poor-quality suture material, incorrectly placed sutures or packing of the abdominal cavity through the wound. Early removal of sutures from the skin or untying sutures that fix the muscles until a durable scar is formed (unfortunately, this also happens), using absorbable sutures instead of non-absorbable ones in the wrong places.

- Features of the patient's body. Diabetes mellitus and anemia, general weakening or flabbiness of muscles, advanced age or cancer cachexia. All these factors lead to a slowdown in wound healing processes, thereby creating the preconditions for their failure. This also includes long-term constipation - in order to go to the toilet, you have to push very hard, and this again puts additional stress on the stitches.

- Inappropriate behavior of the patient - not wearing a bandage, lifting weights in the postoperative period, not following a diet. Still, it depends on the person being operated on no less, and often more, than on the operator. Especially in the postoperative period.

More often than not, several factors play a role. Below I will tell two stories when I encountered this rather formidable and unpleasant complication.

The first story happened in 2009, the first year of residency. We then, most of the time being and working as a ward doctor in a hospital, sometimes went on small additional cycles outside of it - clinical diagnostics, transfusiology, etc. These cycles took place in other institutions - the academy itself, a transfusion station, and so on.

Returning one day after such a two-week course, I again began my duties as an attending physician. Among the patients was a grandfather, over seventy years old, with a tumor of the esophagus. On top of everything else, he was also the father of our procedural sister. Unfortunately, the tumor was not operable and had already reached such a size that it completely blocked the lumen of the esophagus, with only water passing through. He was admitted in a state of extreme exhaustion - in the same state in which the vast majority of patients with his pathology are admitted. The reason for this is the amazing resilience of the Russian people, his reluctance to see doctors and the slowness of medical care, especially in rural areas.

To prevent him from starving to death, my colleagues installed a gastrostomy tube into his stomach. Through a small incision in the abdominal wall and stomach, a fairly thick tube is installed into the lumen of the latter, into which food crushed with a blender is poured with a special large syringe or through a funnel. Naturally, there can be no talk of recovery here, but the painful death of starvation can be avoided.

His condition was improving, and they were slowly preparing for discharge.

Usually, the sutures on the anterior abdominal wall after surgery are removed within 7-8 days. Here, given his age, exhaustion, and the presence of a malignant tumor, I decided to take them off for him on the 11th. It seems to be with reserve.

About twenty minutes after the stitches were removed, I saw some kind of fuss near the patient. The nurse noticed blood on his pajamas and, thinking it was a nosebleed, gave him a diaper and new pajamas. I saw that only the bandage was bloody - there was no nosebleed. Quietly moving the bandage aside, under it I saw a through defect in the wound, a protruding omentum and a loop of small intestine in the depths. Can you imagine my condition – a completely inexperienced and young guy who had just graduated from college and almost killed the father of our nurse!

Urgently taking him to the operating room, we washed the prolapsed organs with antiseptics and re-sutured the wound. This time the stitches were removed much later - on the twentieth day and much more safely.

The second story happened two years later. At that time, I worked in the department with my father, undergoing postgraduate studies at the Department of Surgery on the basis of his department.

We operated on a patient with a huge postoperative ventral hernia. The operators are the manager, and the assistants are me and dad. The operation seemed to go well, but it was a big stretch. For some reason they didn’t cover the defect with mesh - they made do with their own fabrics. Now I don’t remember all the details. But everyone was satisfied with the operation.

Arriving the next morning, we found the patient still on a ventilator. She didn’t want to come out of anesthesia and start breathing on her own. The reason for everything is small belly syndrome. The loops of small intestine that were previously in the hernia now ended up where they were supposed to be - in the abdominal cavity. And the increased pressure through the diaphragm limited the excursion of the lungs and affected the circulatory organs, preventing the organism, which was not accustomed to this, from adapting to new conditions.

We had no choice but to dissolve our plastic and sutured only the skin. Smooth postoperative period. The sutures from the wound were removed on the 14th day.

And at home that same evening there was an eventration of the greater omentum. This is a wide and long fold of the splanchnic (visceral) peritoneum, between the layers of which there is loose connective tissue, rich in blood vessels and fatty deposits.

The frightened patient, seeing blood on the napkin, called her dad, who immediately went to the hospital. At the same time, the patient herself arrived with him. Together with the surgeon on duty, she underwent emergency surgery. Thorough toileting of prolapsed organs. Fortunately, they did not have time to be pinched and die. The omentum was placed back into the abdominal cavity, and the wound was sutured. This time the stitches lasted a very long time - about a month. And with much better results.

Since then, having learned from bitter experience, I always, even after the smallest operations, remove the sutures for my patients in two steps. On the first day I take it off every other day and send it home. The remaining stitches are removed after a couple of days. This simple technique allows the wound to heal better and reduces the risk of eventration or scar failure.

I hope you found the article useful and interesting - I look forward to your feedback. Subscribe to my channel on Telegram.

Modern approaches to the treatment of eventrations

Practical approaches to the treatment of eventrations differ in the ratio of indications for conservative and surgical treatments. The choice of treatment method is determined by the type of eventration, as well as the presence or absence of complications. The vast majority of authors with complete or true eventration are supporters of urgent surgery after short preoperative preparation (B.I. Nikiforov et al., 1982; E.P. Krivoshchekov et al., 1988; S.V. Lokhvitsky et al., 1989; S.G. Grigoriev, 1991). Proponents of operational tactics for other types of events are V.S. Labutina (1970), L.I. Khnoh et al. (1971), Yu.Ya. Makarova (1976), G.A. Bairov et al. (1985), I.M. Mamedov et al. (1986), K.I. Myshkin et al. (1987), G.A. Izmailov (1988), I.G. Leshchenko et al. (1990). With subcutaneous and partial eventration, many authors adhere to conservative tactics. And only when complications such as strangulation of an intestinal loop or the development of secondary peritonitis against the background of subcutaneous or partial eventration occur do they recommend urgent surgical treatment (V.S. Savelyev and B.D. Savchuk, 1976; K.D. Toskin and V.V. Zhebrovsky, 1980; V.K. Gostishchev et al., 1982; E.P. Krivoshchekov et al., 1988; S.G. Grigoriev, 1991).

E.S. Baimyshev (1988) believes that when choosing a method of treating eventration, the following points must be taken into account. Firstly, suturing a non-festering wound during eventration prevents early and late complications and promotes the most favorable results. Secondly, suturing a purulent wound rarely gives a positive result, and if the patient’s condition is serious and there are concomitant diseases and complications, the risk of re-intervention greatly increases. Therefore, when choosing treatment, the surgeon is forced to choose between these tactical paths. S.V. Lokhvitsky and E.S. Baymyshev (1989) distinguishes between absolute and relative indications for surgery. The absolute indications are open eventration with prolapse of organs and its combination with diffuse peritonitis; strangulation of prolapsed organs, phlegmon of the abdominal wall, secondary peritonitis, which complicated the course of unresolved eventration. Relative indications are postoperative eventration of any degree into a “clean” wound without prolapse of internal organs and partial divergence of the wound edges. However, according to these authors, the closer the organs are to the skin level, the greater the extent of the wound and the less pronounced the inflammatory phenomena, the more appropriate it is to surgically eliminate the eventration. It should be remembered that the outcome of conservative treatment is almost always postoperative hernia (K.D. Toskin et al, 1982; E.S. Baimyshev, 1989).

Most surgeons, when deciding on the surgical treatment of eventrations, propose a differentiated approach to aseptic eventrations and eventrations into a “purulent” wound.

The most common method of eliminating aseptic eventration is suturing the edges of a ruptured wound through all layers of the anterior abdominal wall with a thick synthetic thread at a distance of 2–3 cm from the edges of the wound (N.Z. Monakov, 1949; V.S. Labutina, 1970; K.D. Toskin et al., 1980; I.A. Babin et al., 1993). These sutures are fixed on rubber tubes, buttons (B.I. Alperovich et al., 1980; B.A. Akhunjanov et al., 1981; V.I. Petrov et al., 1986) or a gauze tourniquet (D. Veryanu and al., 1972) to reduce the cutting of seams. Some use U-shaped or mattress seams through all layers on rubber tubes (I.M. Mamedov et al., 1986; I.G. Leshchenko et al., 1990). V.S. Savelyev and B.D. Savchuk (1976) recommends the removable 8-shaped suture technique to reduce the cutting of seams. Otteni F. et al. (1972), Fiesenstat M. et al. (1972) use stainless steel wire for suturing the wound through all layers, which is reinforced with buttons or synthetic tubes to reduce the cutting of threads. Ermisch J. (1986) recommends welding with metal grit coated with plastic. The seam is fixed using metal locks or rubber pads. This movable fixation system allows you to change the tension of the abdominal wall. E.V. Kuleshov (1990) uses “permanent” sutures. Sutures placed through all layers at a distance of 1.2 - 1.5 cm from each other are tied one after the other at the end of the operation. As they erupt (on the 8th day), reserve ligatures are tightened, and those that have erupted are removed.

Some authors recommend using double-row seams (leather and all layers) with synthetic threads (Yu.G. Shaposhnikov et al., 1986; V.L. Prikupets et al., 1988; I. Littman, 1985). All the seams described above erupt, weaken after a few days, and no spacers between the thread and the skin prevent the eruption of tissue, because it does not go from top to bottom, but throughout the entire thickness (B.I. Nikiforov et al., 1982).

Some authors recommend a combination of layer-by-layer suturing of the wound with the use of unloading sutures on the aponeurosis (E.V. Ulrich et al., 1979; A.B. Bersenev et al., 1981; G.A. Bairov et al., 1985; V.F. Tskhai, 1988). G.A. Izmailov (1988) suggests fixing the anterior abdominal wall before layer-by-layer suturing of the wound using an extrafocal transtissue fixation device, which allows suturing the wound with minimal time, using thin suture material with maximum tissue adaptation.

There are reports of the successful use of a nylon graft to strengthen the abdominal wall (I.I. Shoshas, 1986), a polyurethane absorbable endoprosthesis polyglactin 910 (Samama G. et al., 1983), an allogeneic dural graft (K.D. Toskin and V. V. Zhebrovsky, 1982).

When suturing aseptic eventration, it is recommended to drain the wound through counter-openings with rubber strips or polyethylene tubes with multiple side holes for administering antibiotics (I.M. Mamedov et al., 1986; I.I. Shoshas, 1986; K.I. Myshkin et al., 1987). With all methods, sutures are removed within 12 to 16 days.

Patients should be operated on under general anesthesia with the use of muscle relaxants. Before suturing the eventration into a “clean” wound, the vast majority of authors recommend treating the wound and prolapsed organs with an antiseptic solution, removing all old ligatures and non-viable tissues, blocking the root of the mesentery with a solution of 0.25% novocaine, and not revising the abdominal cavity in the absence of effusion and clinical signs of peritonitis. produce (V.S. Savelyev et al., 1976; G.A. Bairov et al., 1985; I.A. Babin et al., 1993).

Great difficulties arise in the treatment of eventrations in a “purulent” wound. Despite the large number of proposed methods for eliminating eventration in these conditions, the results of operations remain unsatisfactory (O.B. Milonov et al., 1990), especially in cases where various bronchopulmonary complications occur in the postoperative period against the background of intestinal paresis. Difficulties in bringing together edematous, infected and bleeding tissues are observed in 65–79% of cases (V.M. Udod, 1983; I.M. Mamedov et al., 1986), which significantly reduces the reliability of the suture and creates conditions for its cutting and repeated eventration.

K.D. Toskin and V.V. Zhebrovsky (1982), O.B. Milonov et al. (1990) indicate that when eventration into a “purulent” wound on one side, in the presence of a purulent-necrotic process in the wound, it is impossible to apply a blind suture and ensure reliable strengthening of the abdominal wall to prevent repeated eventration. It is also impossible to carry out full surgical treatment of the wound with the removal of all necrotic tissue, since this leads to the progression of eventration as a result of weakening of the tissue barrier. On the other hand, open treatment of a wound is often accompanied by persistent intestinal paresis, wound intoxication, the occurrence of intestinal fistulas, interloop abscesses, and in the first days of eventration - the risk of secondary peritonitis.

When eliminating eventration into a “purulent” wound, the operation is performed under endotracheal anesthesia. Inspection of the abdominal cavity is recommended only in the presence of purulent or serous effusion (B.I. Alperovich et al., 1978; V.F. Tskhai, 1988; I.G. Leshchenko et al., 1990; A.E. Kostin, 1999 ). The prolapsed organs are treated with antiseptic solutions (furacilin 1: 5000), 60-80 ml of a 0.25% novocaine solution is injected into the root of the intestinal mesentery, necrectomy of the abdominal wall is performed, the omentum is placed over the intestine and then eventration is eliminated in various ways.

To eliminate eventration into a “purulent” wound, some authors propose various configurations of sutures through the wound, which are fixed on buttons, rubber or vinyl chloride tubes located parallel or perpendicular to the wound. These include a mattress seam (I.M. Mamedov et al., 1986), U-shaped seams (I.G. Leshchenko et al., 1990), seams through all layers (B.I. Alperovich et al., 1978 ; B.A. Akhundzhanov et al., 1981; V.F. Tskhai, 1988). The sutures are not tightened until the wound is completely in contact to ensure the free outflow of purulent discharge. Wipes with indifferent ointment and petroleum jelly are placed on the underlying organs, and the gap between the edges of the wound is drained with graduates. In the postoperative period, additional bandages are used. The disadvantage of all these methods is the presence of ligatures in the wound, which complicates dressings and contributes to the formation of intestinal fistulas.

V. S. Savelyev and B. D. Savchuk (1976) proposed eliminating eventration into a “purulent” wound by applying contiguous sutures placed within healthy tissue on rubber tubes, which protect the underlying organs from traumatization by the thread. The seams are not tightened until they are completely close. The wound is treated under ointment bandages. This technique is used by many surgeons (B.A. Akhunjanov et al., 1981; K.D. Toskin et al., 1982; I.I. Bachev, 1989). One of the negative aspects is the formation of postoperative hernias.

A.E. suggests suturing the muscular aponeurotic layer of the wound with a synthetic thread using retaining sutures. Kostin (1999). According to his technique, retaining sutures are placed behind the tissue and behind two Kirschner wires, passed into the sheath of the rectus abdominis muscles parallel to the wound. No sutures are placed on the skin and subcutaneous tissue. In addition, wound drainage must be used according to N.N.’s method. Kanshina (1977) using a perforated tube. With widespread necrosis of the aponeurosis A.E. Kostin (1999) recommends eliminating eventration only with the help of such retaining sutures, and protecting the intestinal loops with perforated polyethylene film. This method has a number of advantages. It completely eliminates the cutting of retaining sutures, which makes it possible to eliminate large diastasis and actively manage patients in the postoperative period, and also prevents the formation of intestinal fistulas. A similar method of wound suturing with metal wires passing through the vagina of the rectus abdominis muscles is used by Yu.V. Kuchin et al. (2004).

Recently, more and more attention has been paid to hardware methods for bringing wounds together, including for the treatment of events into a “purulent” wound. The technique of S.G. is interesting. Izmailov (1997), who proposed using a device that brings the wound together along guide pins drawn perpendicular to the wound through all layers. In this case, the wound is protected with a foam sponge soaked in a 10% xymedon solution. While cleaning the wound and filling it with granulations, the edges of the wound are gradually brought together, followed by suturing. This method also allows you to strengthen the wound of the abdominal wall, prevent the progression of eventration, and actively manage patients, but the danger of intestinal fistulas still remains due to the presence of foreign bodies (wires) in the wound.

OK. Skobelkin et al. (1978) proposed using a continuous CO2 laser for the treatment of purulent wounds, which makes it possible to quickly and simultaneously remove purulent-necrotic tissue and sterilize the wound surface. After which the wound is sutured tightly, leaving a rubber graduate.

V.M. Udod (1983) suggests, after necrectomy, suturing the aponeurosis and skin layer by layer, having previously made laxative skin incisions on both sides of the wound and inserted drains through these counter-apertures with the introduction of a mixture of kanamycin and 20 cm3 of a 0.5% solution of the proteolytic enzyme papain.

E.P. Krivoshchekov et al. (1988), S.G. Grigoriev (1991) propose, after eliminating the eventration, to suture the aponeurosis with interrupted sutures, and leave the subcutaneous tissue open with provisional sutures and pack it with antiseptic napkins. They also consider N.N.’s method promising for this type of wound suturing. Kanshina et al. (1986), who uses deepithelialized skin tape. And in case of a pronounced purulent process after extensive surgical treatment of the wound and necrectomy, they refuse aponeurotic sutures and apply only sutures to the skin, draining the wound with tubular drainages for constant or fractional irrigation of the wound. Moreover, N.N. Kanshin et al. (1986) and M.Yu. Goncharov (1987) recommend using a similar technique to isolate the intestinal loops from the wound by suturing the greater omentum to the parietal peritoneum along the edges of the wound, and K.D. Toskin and V.V. Zhebrovsky (1982) - by suturing an allogeneic preserved dura mater (dura mater) plate. There are cases in the literature of using synthetic mesh for the same purposes (I.I. Shoshas, 1986; Samama G. et al., 1983). Marlex and polyglactin meshes were fixed intraperitoneally, capturing the muscular aponeurotic layer; the edges of the abdominal wall were left not close together. All these techniques make it possible to sufficiently widely excise necrotic tissue in the wound, seal the abdominal cavity, and avoid an excessive increase in intra-abdominal pressure, but they lead to the formation of giant ventral hernias and dysfunction of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall.

I. B. Desyatnikova et al. (2007) also use a polypropylene mesh to close the wound, but after cleansing the wound and forming granulations, they close the wound defect by matching all layers of the abdominal wall wound with sutures, using Kirschner wires inserted in the anterior abdominal wall to bring the edges of the wound closer together.

V.N. Chernyshov et al. (1990) uses local skin grafting to eliminate eventration into a “purulent” wound using tread sutures placed parallel to the wound through the skin and subcutaneous tissue. These loop sutures and fastener straps allow you to bring the skin edges of the wound closer together in a measured manner. As the wound surface cleanses and granulations appear, it is possible to gradually bring the skin edges closer together until they are completely adapted. But the defect in the aponeurosis is not eliminated, and the outcome of such treatment will again be postoperative hernia.

With a combination of eventration and peritonitis P.F. Bytka et al. (1986) propose an open treatment method, when after the main stage of the operation, sanitation and drainage of the abdominal cavity, the intestinal loops are covered with perforated polyethylene film and napkins with antiseptics. The bandage is held in place by several sutures passed through the aponeurosis, which are moderately tightened. Daily dressings under intravenous anesthesia with a change of dressing are recommended, and at intervals of 48-72 hours, sanitation of the abdominal cavity under endotracheal anesthesia.

It should be noted that surgical treatment of eventrations in the postoperative period is necessarily combined with intensive conservative therapy aimed at relieving inflammation, correcting protein, water-electrolyte, acid-base metabolism, coagulation and anticoagulation systems, detoxification, parenteral nutrition and maintaining the functions of vital organs and systems

The main objectives of only conservative treatment of eventration are: prevention of worsening eventration, elimination of the purulent-necrotic process in the wound, prevention of the formation of intestinal fistulas. Prevention of worsening eventration is carried out by prescribing strict bed rest, tightening the edges of the wound with an adhesive plaster, using bandages (K.D. Toskin et al., 1982; E.P. Krivoshchekov et al., 1988; S.G. Grigoriev, 1991; I. Littman, 1985). Elimination of the purulent-necrotic process in the wound is facilitated by complete secondary surgical treatment of the wound (simultaneous or stage-by-stage), during which necrotic tissue is excised, ligatures are removed, and additional opening of purulent leaks and pockets is performed. Then the wound is washed abundantly with antiseptics, loosely tamponed with napkins or a sponge with enzymes, antiseptics, and then with indifferent ointments and vaseline oil (K.D. Toskin et al., 1982; E.P. Krivoshchekov et al., 1988; S. G. Grigoriev, 1991). All this local treatment is carried out against the background of antibiotic therapy and stimulation of regenerative processes (blood transfusion, vitamin therapy, pentoxyl, methyluracil, parenteral administration of protein drugs). Thus, general treatment is aimed at increasing the immune and protective forces of the body (K.D. Toskin et al., 1982; V.M. Udod, 1983; I. Littman, 1985). In the future, physiotherapy is added to local treatment. As the wound is cleansed and granulations appear, secondary sutures are applied (V.K. Gostishchev et al., 1982; K.D. Toskin et al., 1982; S.G. Grigoriev, 1991; I. Littman, 1985), and when A large wound surface and the presence of intestinal fistulas use autodermoplasty with a free split perforated flap, proposed by A.A. Olshanetsky et al. (1990).

In conclusion, it should be said that the question of treating eventrations also remains open. There is no single approach to choosing a treatment method for various types of eventrations.

The first observation of internal organ prolapse through the vagina was described in 1864 by Hyernaux [3]. McGregor in 1907 described the observation of spontaneous vaginal rupture in a 63-year-old woman after lifting “half a ton of coal” [8]. Prolapse of internal organs through the vaginal stump after laparoscopic hysterectomy is quite rare [1, 7, 10-13]. At the beginning of the 20th century, P. Ramirez et al. [9] reported 59 cases of eventration through the vaginal stump after hysterectomy from 1900 to 2001 with an incidence of 0.3%.

H. Hur et al. [2] reported failure of the vaginal stump in 4.9% of cases after laparoscopic hysterectomy, in 0.29% after vaginal hysterectomy and in 0.12% of cases after laparotomic hysterectomy on average 11 weeks after surgery. In earlier publications by P. Iaco et al. [4] stated the incidence of internal organ prolapse at 0.79, 0.25 and 0.26% of observations, respectively. In young patients, prolapse of internal organs has been described in the first 6 months after surgery. In old age, prolapse of internal organs through the vaginal stump was observed at a later date, in particular several years after surgery, and is associated with weakness of the pelvic floor muscles [4-6].

Although eventration of various abdominal organs through the vaginal stump is described in the literature, we have not found a single mention of infringement of an eventrated organ.

Here is an observation.

Patient G.,

46 years old, hospitalized in the surgical department of the Reutov City Clinical Hospital on 10/09/11 as an emergency on the 1st day from the onset of the disease with complaints of constant aching pain in the hypogastric region, dry mouth, bloating.

Considers himself sick during the last 24 hours, when at about 14:00 08.10 pain appeared in the hypogastrium after coitus. She did not treat herself. Subsequently, the pain intensified and became permanent. Hyperthermia reached 38 °C. Due to increased pain, she turned to the Reutov Central City Hospital.

Among the past diseases, he notes childhood infections. Operations: appendectomy in 1985, hysterectomy for endometrial hyperplasia, uterine fibroids in June 2010.

At the time of examination, the condition was of moderate severity. Consciousness is clear. The patient has a normal build and normal nutrition. The skin and visible mucous membranes are of normal color. Body temperature 38.3 °C. NPV 16 per minute. Auscultation: vesicular breathing, no wheezing. Heart sounds are clear, rhythmic, pure, no pathological noises are heard. Heart rate 78 per minute, blood pressure 130/80 mm Hg. The tongue is dry, covered with a white coating. The abdomen is of regular shape, moderately swollen, in the right iliac region there is a postoperative keloid scar measuring 12x1 cm without signs of inflammation. On palpation, the abdomen is soft, sharply painful in the hypogastric region, where protective muscle tension is detected. No infiltrative or tumor-like formations were detected in the abdominal cavity; the Shchetkin-Blumberg sign was positive in the hypogastric region. Peristaltic sounds are sluggish, no pathological bowel sounds are heard. Tapping on the lumbar region is painless. Physiological functions are not impaired.

Per rectum: sphincter tone is preserved, tumor-like formations are not detected at the height of the finger. On palpation along the anterior wall of the rectum, sharp pain is detected. Per vagina: the presence of a fatty pendant and a section of the colon in the vaginal lumen was revealed.

Blood leukocytes 12.2·109/l.

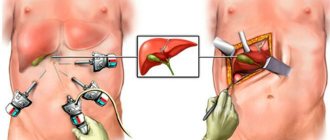

09.10 - surgery for urgent indications: elimination of eventration. Laparoscopic suturing of the vaginal stump, sanitation, drainage of the abdominal cavity.

Carboxyperitoneum was applied through a Veress needle to an intra-abdominal pressure of 12 mm Hg. A video camera and manipulators (1×5, 1×10 and 1×10 mm) are introduced through typical points. An examination of the liver, gallbladder, and spleen revealed no pathological changes. In the abdominal cavity there is up to 100 ml of cloudy serous effusion, mainly in the pelvic cavity. The effusion was aspirated. From the vaginal stump, a strangulated portion of the sigmoid colon with a fat suspension was inserted into the abdominal cavity (see figure).

Figure 1. Intraoperative photographs of patient G. a - parietal entrapment of the fatty suspension of the sigmoid colon.

Figure 1. Intraoperative photographs of patient G. b - incompetent vaginal stump.

Figure 1. Intraoperative photographs of patient G. in - intracorporeal suture of the vaginal stump. The latter with injected vessels. During instrumental examination, the wall of the sigmoid colon is pinched parietally and is viable. The vaginal defect measuring 3x4 cm was sutured with two single interrupted 2/0 Vicryl sutures. A drainage is installed in the pelvic cavity to the suturing site. The abdominal cavity was sanitized with 500 ml of antiseptic and drained. Desufflation was performed and the wounds were sutured.

Postoperative course without complications. The patient was discharged 7 days after surgery.

According to various authors, the number of eventrations is progressively increasing with the introduction of video endoscopic technologies into practice, so, according to various sources, their number after laparoscopic and robot-assisted hysterectomy reaches 5%. H. Hur et al. [2] provide data from a survey of 7039 patients after hysterectomy. In 8 out of 10 cases, failure of the vaginal stump occurred after laparoscopic hysterectomy, which is 2%. All 8 patients were young (average age 39 years), and the technique of vaginal suturing was no different from the traditional one. The authors believe that the access and technique of suturing the vaginal stump do not affect the incidence of vaginal stump failure [2, 4]. P. Iaco et al. [4] compared 1440 patients who underwent hysterectomy with suturing of the vaginal stump and 2330 without suturing. There was no significant difference in the incidence of internal organ prolapse.

It is necessary to make a reservation that when a patient is admitted with a clinical picture of nonspecific abdominal pain in the absence of a picture of intestinal obstruction on an x-ray and unexpressed changes in laboratory tests, the differential diagnosis of abdominal pathological changes is difficult. Acute abdominal pain in women can be a manifestation of various pathological changes in internal organs, including acute gynecological diseases.

In our observation, the cause of pelvioperitonitis before laparoscopy remained completely unclear.

Panhysterectomy is currently completed with a hardware or manual suture of the vagina. In this case, patients are recommended to have “sexual rest” for 2-3 months. In the patient we observed, the postoperative period after hysterectomy, occurring with symptoms of prolonged colporrhagia, and the early onset of sexual activity contributed to the formation of incompetent vaginal stump with subsequent prolapse of the sigmoid colon and Richter's strangulation. The use of laparoscopy made it possible to establish the correct diagnosis and carry out timely surgical treatment.