A benign stomach tumor is a neoplasm that has no signs of a malignant process. In some cases, there remains a small risk of degeneration in the absence of appropriate treatment. Benign neoplasms of the stomach account for up to 5% of all tumor diseases of the stomach; they can develop from epithelium, nervous tissue, fatty structures or vascular ones. Growth can be fast or slow. According to the direction of growth, tumors are distinguished that move towards the lumen of the stomach, towards the abdominal organs and neoplasms that grow inside the wall. According to localization, they occur with equal frequency in the body of the stomach, antrum or other places.

At CELT you can consult a surgeon.

- Initial consultation – 3,000

- Repeated consultation – 2,000

Make an appointment

Types and characteristics of gastric tumors

Based on their origin, all neoplasms localized in the stomach area are divided into two large groups: epithelial and non-epithelial.

Among the first group there are adenomas and polyps (single or in groups). The difference is that polyps are outgrowths into the lumen of an organ; they are usually round in shape and have a wide base; they can be located on a stalk. The development of polyps is associated with age-related changes - they are more common after the age of 40, the disease affects men more often than women. Histologically, the polyp is an overgrown glandular and epithelial tissue with connective tissue elements and a developed network of blood vessels.

Adenomas are true benign neoplasms consisting predominantly of glandular tissue. Unlike polyps, adenoma can degenerate more often. But they are less common than polyps.

Nonepithelial tumors are rare. They form in the wall of the stomach and can consist of a variety of tissues.

Non-epithelial neoplasms include:

- Myoma is formed from muscle tissue.

- Neuroma is formed from the cells that make up the myelin sheath of nerve fibers.

- Fibroma - develops from connective tissue.

- Lipoma – consists of adipose tissue.

- Lymphangiomas - tumor cells originate from the walls of lymphatic vessels.

- Hemangiomas are made from cells lining blood or lymph vessels.

- and other options, including tumors of mixed nature.

Unlike polyps, which are more common in men, non-epithelial tumors are more often diagnosed in women. All such neoplasms have distinctive features: as a rule, they have a clear contour, smooth surface, and rounded shape. They can grow to significant sizes.

A non-epithelial tumor, leiomyoma, is especially distinguished - it occurs with a higher frequency than other neoplasms from this group. This tumor can cause gastric bleeding or potentiate the formation of ulcers by growing into the gastric mucosa. All non-epithelial neoplasms are characterized by a fairly high risk of oncological degeneration - malignancy.

Risk factors

Tumors in the stomach occur more often in people who:

- suffer from chronic diseases of the digestive system;

- have an active Helicobacter pylori infection (microorganisms lead to damage to the mucous membranes of the gastrointestinal tract and a decrease in their protective properties);

- do not comply with the principles of rational, balanced nutrition;

- have a genetic predisposition to tumors;

- live in environmentally unfavorable areas;

- systematically exposed to adverse factors (chemical compounds, stress, trauma, etc.);

- have an immunodeficiency;

- have bad habits (alcohol, smoking, etc.).

The risk group includes people over 40 years of age who do not undergo annual preventive examinations with mandatory examination of the stomach.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a stomach tumor are usually mild. If the tumor does not grow, it practically does not appear and is not observed in any way. Very often, benign tumors are determined by indirect signs or detected accidentally during endoscopic examination.

The clinical picture includes:

- Manifestations characteristic of gastritis, but without sufficient diagnostic signs to make a diagnosis of gastritis.

- Hemorrhage in the stomach.

- Decreased appetite, fatigue, weight fluctuations are common disorders that can be associated with diseases of the digestive system.

- Dyspepsia.

- With frequent hemorrhages - anemia.

With an absolutely calm course, dull and aching pain may be observed, localized, as a rule, in the epigastrium. Pain often occurs after eating. Quite often, patients associate these symptoms with gastritis.

With tumors that are large enough, more pronounced manifestations may be observed. Heaviness appears, attacks of nausea occur, and frequent belching appears. Patients find blood admixtures in their vomit and stool. Laboratory tests determine low hemoglobin. Patients experience weakness and dizziness. Regardless of the preservation of normal appetite, weight loss begins. In total, there are more than a hundred types of benign neoplasms - with different courses and clinical presentations. The severity of symptoms depends on the location, size and growth rate of the tumor. The classic clinical picture that allows one to suspect a tumor is bleeding, accompanied by general disturbances in the gastrointestinal tract.

Own clinical observation of GIST

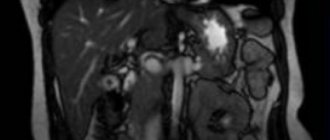

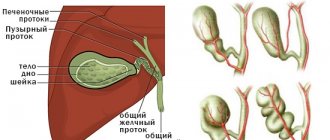

Patient B., 67 years old, in March 2022, consulted a therapist at her place of residence with complaints of mild pain in the epigastrium, episodes of dizziness due to pain, nausea after eating, heartburn, and pain in the hypogastrium not associated with the act of defecation and urination. Daily stool, type 4 according to the Bristol scale, without pathological impurities. The deterioration of health has been noted in the last 2 months. For a long time he has been suffering from chronic gastritis and chronic non-calculous cholecystitis. On physical examination, the condition is satisfactory; no pathological changes in the cardiovascular and respiratory systems were detected; the abdomen is not swollen, soft, painful on palpation in the epigastrium, in the projection of the transverse colon. Blood tests are within reference values. According to an ultrasound of the abdominal organs dated 04/08/2019, the liver is not enlarged, its echogenicity is not changed, the diameter of the portal vein is 10 mm, the diameter of the common bile duct is 4 mm; gallbladder with kinks, walls 2 mm, not thickened, echo-positive mobile sediment in the lumen; The pancreas measures 16×10×14 mm; a hypoechoic formation of 21×20 mm is located in the body area. To clarify the nature of the identified changes, on April 23, 2019, the patient underwent a CT scan of the chest and abdominal cavity with intravenous contrast (iopamidol). A series of images of the lungs on both sides revealed lesions with clear, uneven, tuberous contours, accumulating a contrast agent with an increase in density from 13 HU to 93 HU (on the right in S3 with dimensions of 8x10 mm, in the axillary subsegment - up to 7 mm, on the left in S5 - up to 3 mm), small areas of compaction of lung tissue in S6 on the left and S9 on the right. No enlarged intrathoracic lymph nodes were detected. A series of images of the abdominal organs along the posteromedial wall of the upper third of the stomach revealed a formation located outside the stomach, measuring 18x21x13 mm, with clear contours, accumulating a contrast agent with an increase in density from 41 HU to 71 HU (Fig. 1).

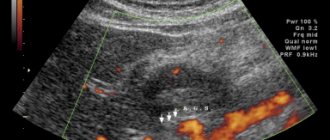

The formation is adjacent to the wall of the stomach for about 10 mm. The structure of the liver parenchyma is homogeneous and evenly accumulates the contrast agent. Intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts are not dilated. The gallbladder is not enlarged, its contents are homogeneous, no radiopaque stones were detected, and there is no thickening of the wall. The portal and splenic veins are not dilated, the spleen is not enlarged, and has a homogeneous structure. The pancreas is not enlarged, has a homogeneous structure, no foci of pathological accumulation of the contrast agent have been identified, and the parapancreatic tissue is not infiltrated. Thoracic and lumbar spine with degenerative-dystrophic changes. The structure of the bodies of the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, as well as the iliac bones, is heterogeneous due to multiple zones of rarefaction of the bone structure with clear contours. Zones of osteosclerosis are detected in the body of L4 (4 mm) and in the body of the left ilium (4×6 mm), hemangioma in the body of Th9. To clarify the nature of bone changes, osteoscintigraphy was performed; no convincing evidence of a specific skeletal lesion was obtained. Taking into account the identified exophytic formation emanating from the stomach, on April 30, 2019, the patient underwent a standard endoscopic examination: the esophagus is freely passable, the mucous membrane is hyperemic, and a cheesy, non-displaceable whitish coating is detected throughout. The cardia rosette gapes. The mucous membrane of the stomach prolapses into the esophagus, in the area of the esophageal-gastric junction - Shatsky's ring with vulnerable mucosa in this area. The shape of the stomach is not changed. The mucosa is diffusely hyperemic, in the antrum there are 4 acute erosions under fibrin measuring up to 3 mm. Along the posterior wall of the stomach, slight compression of the gastric lumen from the outside is visualized against the background of unchanged mucosa (Fig. 2). To clarify the nature of the neoplasm, on June 17, 2019, the patient underwent an EUS: in the upper third of the body of the stomach along the lesser curvature, closer to the posterior wall, a submucosal formation up to 15 mm in size, round in shape, moderately protruding into the lumen of the stomach without deformation, covered with unchanged mucosa, was detected. The formation is dense on instrumental palpation. When scanning the stomach wall with a frequency of 7.5–12 MHz, a rounded, inhomogeneous, predominantly hypoechoic formation up to 20 mm in size, emanating from the muscular wall, with predominant extraorgan growth, with pronounced blood flow is determined (Fig. 3).

After antimycotic therapy (fluconazole 150 mg/day for 14 days), on July 10, 2019, the patient underwent enucleation of an extraorgan formation of the gastric body using endoscopic video assistance. Histological examination of the removed formation: round, clearly encapsulated mesenchymal, 2.7 cm in diameter, represented by spindle-shaped cells without cellular polymorphism with an abundant collagen matrix. The picture is most typical for the sclerosing variant of GIST. The material was sent for additional research to the National Center for Clinical Morphological Diagnostics LLC, where a pathohistological examination of the remote lesion was performed on July 10, 2019. Macrodescription: round dense node with a diameter of 2.7 cm with a coarsely lumpy surface, gray, fibrous in section, with multiple pinpoint hemorrhages. Microdescription: a clearly demarcated mesenchymal neoplasm with a diameter of 2.7 cm is represented by spindle-shaped cells with smooth muscle differentiation, with minimal cell-nuclear polymorphism, and areas of abundant collagenization. The picture is most typical for the sclerosing variant of GIST (Fig. 4). An IHC study reveals the structures of a spindle cell tumor in the material, in places with a moiré pattern, focal fibrosis and hyalinosis. Mitotic activity is low - less than 5 mitoses per 5 mm2 at a magnification of 400. Tumor cells intensely express CD34, DOG1, focally express desmin and do not express S-100 protein (Fig. 5). The index of proliferative activity Ki-67 is within 2–5%. Conclusion: the histological picture and immunophenotype of the tumor correspond to gastrointestinal stromal tumor, GIST, group 2. The patient was referred for surgical treatment.

Causes

To date, all the causes of the formation of benign stomach tumors are unknown. Therefore, it is correct to talk about risk factors - factors that provoke pathological processes leading to the appearance of tumors. These include the presence of other gastrointestinal diseases.

The most current theory is that polyps appear as a result of disturbances in the natural regeneration of the gastric mucosa. Therefore, polyps often develop against the background of gastritis. Adenomas are often accompanied by atrophic gastritis. It was noted that more than 70% of all neoplasms develop in the lower third of the stomach - that is, in an area with a low concentration of hydrochloric acid.

The cause of the development of nonepithelial tumors may be embryonic disorders or the presence of chronic diseases. Since specific causes cannot be identified, there is no specific prevention of benign tumors. We must not forget about hereditary predisposition - patients whose relatives had gastric tumors must undergo an endoscopic examination, even in the absence of any symptoms of stomach disease. In any case, if you suspect the presence of a polyp or polypoid formation of the stomach, you should contact a surgeon.

Causes of development of nonepithelial tumors of the stomach

The exact cause of tumors is unknown, but predisposing factors are believed to be:

- chronic gastritis, especially accompanied by low stomach acidity;

- decreased immunity;

- heredity - stomach tumors are often observed in close relatives;

- improper and irrational nutrition;

- reproduction inside the stomach by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori;

- smoking, alcohol abuse; industrial contact with substances that stimulate tumor growth.

Our doctors

Gordeev Sergey Alexandrovich

Surgeon, Candidate of Medical Sciences, doctor of the highest category

42 years of experience

Make an appointment

Prokhorov Yuri Anatolievich

Surgeon, head of the surgical service of CELT, candidate of medical sciences, doctor of the highest category

33 years of experience

Make an appointment

Fedorova Elena Vladimirovna

Surgeon, Candidate of Medical Sciences, doctor of the highest category

22 years of experience

Make an appointment

Lutsevich Oleg Emmanuilovich

Chief Surgeon of CELT, Honored Doctor of the Russian Federation, Chief Specialist of the Moscow Department of Health in Endosurgery and Endoscopy, Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the Department of Faculty Surgery No. 1 of the State Budgetary Educational Institution BPO MGMSU, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Doctor of the Highest Category, Professor

43 years of experience

Make an appointment

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) of the stomach account for 3–6% of all NETs and about 2% of all gastric tumors.

Gastric NETs are more common in women (64%) [1]. Highly differentiated type I NETs predominate (see classification). Poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas occupy no more than 6% of the gastric NET structure, but their true prevalence may be underestimated due to the difficulties of morphological diagnosis [2]. For a long time, gastric NETs were considered extremely rare diseases, but in recent years there has been a steady upward trend in their incidence. Thus, according to the National Cancer Institute, during the period from 1950 to 1999, only 562 cases of gastric NETs were registered, and from 2000 to 2004 – already 1043, which amounted to 11.7% of the total number of gastroenteropancreatic NETs [3, 4 ] The reasons for such a rapid increase in incidence are unknown. In part, the increase in the number of primary patients may be a consequence of the widespread introduction of endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and immunohistochemical examination of biopsy material [5]. An opinion has also been expressed about the role of the use of proton pump inhibitors in the development of type I gastric carcinoids. Long-term (years) use of drugs in this group and the achlorhydria they cause are accompanied by a pronounced increase in the level of gastrin-17, which is one of the key pathogenetic mechanisms for the development of gastric carcinoids [6–8]. Gastric NETs are a heterogeneous group, including both highly differentiated neoplasms that are subject to endoscopic treatment and characterized by a favorable prognosis, as well as high-quality low-grade tumors with a high metastatic potential, characterized by an extremely aggressive course and unfavorable prognosis, for which surgical and combined treatment is performed, as in gastric adenocarcinomas . Low awareness of general practitioners and oncologists of the general medical network about this problem often leads to an erroneous choice of treatment tactics, in particular to unnecessary operations in patients with gastric carcinoids of types I–II.

Classification of gastric NETs

The concept of “carcinoid” was first introduced by Oberdorfer in 1907 to describe gastrointestinal tumors that have a specific morphological structure different from that of epithelial neoplasms [9]. In 2007, the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society (ENETS) first proposed a classification of NETs, which used a system for determining the degree of tumor differentiation, similar to that for all malignant neoplasms of the gastrointestinal tract [10, 11]. In the 2010 recommendations, the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) proposed dividing all gastrointestinal NETs according to the degree of differentiation (G) depending on the mitotic index and the percentage of cells expressing the Ki-67 antigen [12]. It is this approach that became the basis for the creation of the current WHO classification for NEO of the gastrointestinal tract, according to which NEO G1, G2, neuroendocrine carcinomas G3 (small and large cell), as well as mixed adenoneuroendocrine carcinomas and hyperplastic or pretumor changes are distinguished [13 ].

In 1993, Italian pathologist G. Rindi proposed a classification dividing gastric carcinoids into three main types. Type I carcinoids (up to 70–80% of the total number) [14, 15] develop against the background of atrophic autoimmune gastritis, incl. with pernicious anemia [16]. In the presence of this disease, a significant increase in gastrin levels occurs as a response to achlorhydria, which in turn leads to hyperplasia of gastric neuroendocrine cells and the appearance of multifocal carcinoid tumors (Fig. 1). This theory is supported by animal experiments, which revealed a significant increase in the incidence of gastric NET development in the presence of high doses of proton pump inhibitors [8]. According to their cellular origin, type I carcinoids are ECL-omas, i.e. tumors of enterochromophin-like (ECL) cells. They are characterized by multiplicity of primordia, polypoid growth and low metastatic potential. As a rule, type I carcinoids have a high degree of G1 differentiation (sizes up to 1 cm) and are localized within the mucous-submucosal layer of the stomach (Fig. 2)

Type II carcinoids (about 5%) are also ECL-omas and arise due to increased gastrin levels, but unlike type I, the cause of hypergastrinemia is a functioning NEO - gastrinoma (Solinger-Elison syndrome; Fig. 3). Gastrinoma can occur sporadically (up to 70%) or develop as part of multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN-I) syndrome [17]. In the pathogenesis of such tumors, not only hypergastrinemia is important, but also inactivation of the MEN1 gene. They are also characterized by multiplicity of primordia, polypoid growth and superficial localization, however, these tumors more often have moderate G2 differentiation and have a higher metastatic potential (up to 10%; Fig. 4).

Type III NETs, which account for up to 20% of all gastric carcinoids, are characterized by sporadic occurrence in the absence of hypergastrinemia and atrophic gastritis (Fig. 5). These tumors, usually solitary and larger than 2 cm, are prone to invasive growth and have a more aggressive course with a high potential for regional and distant metastasis [18]. According to the degree of differentiation, they are always G2.

A separate type of gastric NEC are poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NEC), some authors designate them as type 4 according to Rindi (Fig. 6). This group includes only tumors with low differentiation grade (G3), high Ki-67, has no association with underlying conditions and is characterized by an extremely poor prognosis (median survival of about 12 months). There are small cell and large cell variants. Particular difficulties arise when trying to classify tumors with differentiated morphology but a high mitotic index and Ki-67 >20% but <50%. According to the WHO classification, these tumors should be classified as gastric NEC G3 (type 4), however, in their biology, clinical course and response to chemotherapy, they are more consistent with type III gastric carcinoids. There is currently no consensus on this matter. In the coming years, it is planned to revise the WHO classification with the allocation of differentiated NEC into a separate group. Comparative characteristics of the presented groups of NETs are given in Table. 1.

The WHO and G. Rindi classifications do not contradict each other and can be combined in one table (Table 2).

Diagnostics

Multimodal esophagogastroduodenoscopy

The endoscopic method of examination is of greatest importance in the diagnosis of gastric NETs, but white light endoscopy (WLI) often does not allow differentiating NETs and benign polypoid formations of the stomach. Currently, for a more precise diagnosis of gastric NETs, multimodal endoscopic examination is used, including examination of the mucous membrane in white light with high resolution (WLI-HD), narrow-spectrum endoscopy (NBI), incl. with close focus (NBI-CF) and optical image magnification (NBI-ME) [19–22]. A mandatory method of examination for gastric NET is endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), performed to assess the depth of tumor invasion into the gastric wall and identify possible metastatic lesions of regional lymph nodes [23, 24].

Gastric NETs are often mistaken for hyperplastic polyps, fundic gland polyps, chronic erosions, and even submucosal neoplasms [25], however, pathognomonic endoscopic criteria have now been developed for the differential diagnosis of gastric NETs of all types. Thus, during endoscopic examination in white light, type I gastric NETs in the vast majority of cases are visualized as multiple brightly hyperemic flat formations ranging in size from 0.2 to 0.5 cm, localized in the body and proximal parts of the stomach. Against this background, pronounced atrophy of the mucous membrane is clearly defined, characterized by thinning of the mucous membrane and its whitishness caused by fibrotic changes (Fig. 2A) [21, 22, 26]. Less commonly, in type I NETs, a polypoid form of growth is observed, however, unlike hyperplastic polyps, type I NETs do not have “legs” and, similarly to flat variants, are characterized by severe hyperemia, which is due to their significant neovascularization. When using NBI, type I NETs are characterized by a punctate or tortuous pit architecture, as well as pathological tortuosity, dilatation, and excess numbers of mucosal collecting venules (Figure 2B) [19–22]. In the vast majority of cases, type I NETs are localized within the mucous membrane and with EUS are visualized as hypoechoic formations emanating from its deep parts [21]. A similar endoscopic picture is observed in type II gastric carcinoids (Fig. 4).

Type III NETs are most often mistaken for hyperplastic polyps because... always have a polypo- or plaque-like shape and wide bases (Fig. 5A) [27]. In narrow-spectrum endoscopic examination of NBI, type III NETs are characterized by tortuous or irregular pit architecture and, like type I NETs, pathologically tortuous dilated mucosal collecting venules (Fig. 5B) [27]. In contrast to type I–II NETs, type III gastric carcinoids often invade the submucosal layer, which can be clearly detected by EUS (Fig. 5C) [23, 24].

With poorly differentiated NEC, the endoscopic picture is generally similar to diffuse type gastric cancer. Differential diagnosis is based on the results of a biopsy and immunohistochemical study (Fig. 6).

Thus, a comprehensive multimodal endoscopic examination, including WLI-HD, NBI and endosonography (EUS) [21, 22], can accurately determine the type of gastric NET.

Radiation imaging methods

Ultrasound, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used to determine the location, extent, and depth of invasion of the primary tumor (type III carcinoids and NEC), as well as to identify regional and distant metastases. The standard examination for gastric NETs is spiral CT with intravenous contrast. The best visualization with intravenous contrast is achieved in the early arterial phase [28, 29]. An alternative method is MRI, which allows you to visualize the tumor without contrast. A number of studies have demonstrated a higher efficiency of MRI for detecting liver metastases in NETs compared with scintigraphy with labeled somatostatin analogues and standard spiral CT [30]. It is for this reason that MRI, in accordance with ENETS recommendations, is the preferred technique for detecting and monitoring NET metastases in the liver [31]. In poorly differentiated NEC G3, to assess the extent of the process, it is recommended to perform a spiral CT scan of three zones: the chest, abdomen and pelvis [31].

Octreotide, 111In

Scintigraphy with a (111In) labeled somatostatin analogue is used to diagnose common forms of well-differentiated gastric NETs, mainly type III (G2). Since the incidence of regional and distant metastases in type I–II carcinoids is extremely low, there are usually no indications for radioisotope scintigraphy [32–34]. For poorly differentiated NEC, this method is ineffective and should not be routinely used for diagnosis.

X-ray of the stomach under double contrast conditions

X-ray examination with double contrast is a routine examination method for patients with malignant tumors of the stomach, allowing to determine the location, extent and growth pattern of the formation. There are no pathognomonic signs of NET, and the radiographic picture depends solely on the type of tumor growth and is similar to that observed with other epithelial neoplasms. For flat NETs of types I–II, double-contrast gastric radiography does not allow visualization of even multiple tumors and is not routinely used.

Biochemical markers

Measuring fasting serum gastrin concentration is a key method for differential diagnosis of NET types I, II and III. As noted earlier, an increase in gastrin levels is the main pathogenetic factor in the development of type I–II gastric carcinoids and their pathognomonic feature [16]. An indicator of <40 is considered normal iii=»» 2-=»» 2=»» 35=»» p=»»>

Chromogranin A (ChgA) is a universal marker of NETs. Measuring the concentration of ChgA in the blood serum is a sensitive, but low-specific method for diagnosis and monitoring of NETs, incl. hormonally inactive [36, 37]. In gastric NET types I–II, CgA is always elevated, but the cause of this is not the appearance of carcinoids, but chronic hypergastrinemia with hyperplasia of the neuroendocrine apparatus of the stomach. Therefore, this marker is of clinical significance only for type III gastric carcinoids. Also, the correctness of HgA measurement is affected by the use of proton pump blockers and the presence of renal or liver failure. In the first case, to obtain the correct result, you should stop taking the drug before drawing blood or replace it with an H2-histamine receptor blocker [38]. ChgA monitoring is ineffective and should not be used in gastric NEC G3.

Classic or atypical (caused by histamine overproduction) carcinoid syndrome is extremely rarely observed in gastric NETs, mainly in type III tumors [39]. In this case, the daily amount of 5-HIAA (5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid) in urine is determined, which has high specificity for the diagnosis and monitoring of serotonin-producing NETs. The normal level is 2–8 mg/day. The clinical utility of this test is limited by the possibility of false-positive results. An increase in 5-HIAA levels up to 30 mg/day may be a consequence of malabsorption syndrome, eating foods rich in tryptophan and serotonin, or taking a number of medications (for example, acetaminophen, barbiturates, ephedrine, nicotine, caffeine, etc.) [40].

Treatment

Localized NETs

The choice of treatment for NETs depends on their type and degree of differentiation. The “golden” standard of treatment for patients with NET types I and III is intraluminal endoscopic treatment [16, 41]. Since most type I NETs have invasion within the mucous membrane, endoscopic mucosal resection or argon plasma coagulation are most often used to treat such patients. For type I polypoid NETs, the optimal treatment method is mucosal resection (MRM) [21]. The first stage is the formation of a hydraulic cushion under the tumor in order to separate it from the submucosal layer. Then, a fragment of the mucous membrane with NET is cut off within healthy tissues using an electrosurgical unit and a diathermic loop [42]. The criterion for the radicality of such an endoscopic intervention is the absence of tumor cells at the edges of the removed fragment of the mucous membrane [42]. ERS provides a high degree of radicalism and a relapse-free course of the disease [22]. For multiple flat type I NETs, the most effective treatment method is endoscopic argon plasma coagulation using specialized electrosurgical units and argon supply catheters inserted into the instrumental channel of the endoscope. This approach ensures deep, down to the lamina propria, dry necrosis of the mucous membrane in the tumor area, which makes it possible to achieve a high degree of radical intervention [22, 43].

If it is impossible to perform radical endoscopic treatment or achieve an adequate relapse-free period during treatment, a number of authors suggest performing anthrumectomy. This intervention leads to a significant decrease in the number of gastrin-producing cells located in the antrum of the stomach, and as a result, a decrease in gastrin levels with subsequent regression of tumor tissue [14, 16, 44, 45]. Indications for the use of more aggressive methods of surgical treatment are invasion of the muscular layer of the gastric wall [46]; tumor size >2 cm, which significantly increases the risk of regional metastasis [17]; impossibility of performing radical endoscopic treatment [35]; as well as gastrointestinal bleeding if it is impossible to perform adequate endoscopic hemostasis [47]. The issue of using conservative treatment methods for type I NETs, such as taking dilute hydrochloric acid or using somatostatin analogues, remains controversial. Therefore, these approaches can only be recommended in cases where endoscopic or surgical treatment is not possible [45, 48–50].

With NET type II, as with type I, endoscopic treatment methods are used, as well as somatostatin analogues, however, the prognosis for such patients is largely determined by the success of treatment of the underlying disease, i.e. gastrinomas [16, 39, 51].

The main treatment method for type III gastric NETs and poorly differentiated G3 NECs is surgical intervention involving gastrectomy or gastrectomy with regional lymphadenectomy [48, 52, 53]. In case of invasion of a well-differentiated type III tumor within the mucous membrane or submucosal layer, it is possible to perform intraluminal endoscopic treatment in the amount of endoscopic resection of the mucous membrane with dissection in the submucosal layer [54].

For small cell gastric cancer, independent conservative therapy (chemotherapy, chemoradiotherapy) is possible, since the results of surgical treatment are unsatisfactory and differ little from those with conservative treatment [55, 56].

Metastatic NETs

Highly differentiated NETs.

In the case of metastatic gastric NETs, surgical intervention in relation to the primary site and distant metastases, in particular in the liver, is justified in the presence of an atypical carcinoid syndrome or if cytoreduction in the volume of R0 is possible [57–59]. Moreover, complete cytoreduction significantly improves overall survival rates [57–64]. In all other cases, conservative treatment remains the optimal method.

According to the PROMID and CLARINET studies, the use of somatostatin analogues in metastatic unresectable NETs has an antiproliferative effect, increasing the time to progression and overall survival rates, regardless of the hormonal activity of the tumor [31, 65, 66]. Based on the data obtained, therapy with high doses of somatostatin analogues (octreotide 30 mg every 28 days, lanreotide 120 mg every 28 days) is the standard treatment for metastatic forms of well-differentiated gastric NETs, mainly in type III. As a second line of therapy, it is possible to use targeted therapy (everolimus) and chemotherapy, but the effectiveness of such treatment for gastric NETs has not been confirmed by serious studies.

Poorly differentiated NETs.

For generalized G3 NETs, the first-line treatment regimen is a combination of cisplatin and etaposide [67], while second-line therapy is currently not available [31]. In a recent retrospective study, the use of temozolomide and capecitabine in this group of patients achieved a partial response in 33% of participants, which requires further study of this combination of drugs [68]. Also, quite optimistic preliminary results were obtained using fluorouracil or capecitabine in combination with oxaliplatin or irinotecan [69, 70]. Regarding the use of drug therapy in the adjuvant setting, only one small (n=52) study was conducted in a group of patients after liver resection who received a combination of fluorouracil and streptozotocin. There were no statistically significant differences in survival rates between the study and control groups, as well as the historical control group [71].

conclusions

Gastric NETs are a heterogeneous group of diseases that differ in clinical course, approaches to therapy, and prognosis. The correct choice of treatment tactics is based on determining the neuroendocrine nature of the tumor and its type according to existing classifications. Treatment of patients with gastric NETs can vary from minimally invasive endoscopic techniques (carcinoid types I, II) to aggressive combined and complex treatment programs (NEC G3), therefore awareness of the differences between different types of gastric NETs is a key factor in choosing treatment tactics.

Diagnostics

Diagnosis of stomach tumors consists of three main stages: history taking, examination, radiographic and endoscopic examination. A blood test is also prescribed, which can detect a decrease in hemoglobin levels, that is, anemia, characteristic of tumors that cause bleeding. The benign quality of a neoplasm is determined by the following characteristics: size, presence of peristalsis (during instrumental examination), shape. Fuzzy contours, rapid growth and lack of peristalsis indicate that the polyp is malignant.

To clarify the diagnosis, endoscopy is used - esophagogastroduodenoscopy, which allows you to visually assess the condition of the mucosa and see in real time the shape and size of tumors localized on the mucosa. This method allows you to assess the risk of malignancy - it is visually impossible to distinguish an early-stage malignant tumor from a benign one; a biopsy is required. If oncology is suspected, during FGDS, a sample is taken for histological examination in the laboratory - a biopsy allows you to accurately determine the nature of the neoplasm.

Since non-epithelial tumors come in a wide variety, it is often possible to make a final diagnosis only after surgery.

The study of tumors located outside the mucosa is possible using the same means: contours are visible on radiography, and endoscopic examination in combination with ultrasound (endo-ultrasound) allows us to determine areas of compression that appear when tumors grow inside the walls of the stomach or towards internal organs.

Colon

Visualization of a pathological focus in the large intestine necessitates its pathohistological evaluation. If the number of polyps is too large for simultaneous removal, a representative number of pieces should be taken. The smallest polyps detected during screening sigmoidoscopy should be biopsied; larger polyps should be removed entirely during a subsequent colonoscopy. Morphological confirmation of the presence of an adenoma or adenocarcinoma should serve as a reason for examining the entire colon. Published data on the value of identifying hyperplastic polyps during sigmoidoscopy remain controversial. Many US gastroenterologists do not believe that these polyps carry an increased risk of severe proximal neoplasia.

For colitis, endoscopic examination with biopsy helps in establishing the extent of the process, differential diagnosis and treatment planning. An acute biopsy in a patient with bloody diarrhea can distinguish spontaneously resolving acute colitis from a primary or recurrent attack of chronic ulcerative colitis or ischemic colitis. Terminal ileal biopsy may be helpful in the diagnosis of Crohn's disease, infectious ileitis, and lymphoid nodular hyperplasia. Both Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis are associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer. For these diseases, in order to identify dysplasia, it is recommended to conduct an endoscopic examination 8 years after the initial diagnosis, if the process was right-sided. In patients with left-sided localization of pathological changes, the risk of developing cancer increases by the 15th year from the onset of the disease. In patients with pancolitis, the most commonly used approach is 4-quadrant sampling every 10 cm (every 5 cm over the distal 25 cm). In left-sided colitis, a biopsy from the proximal colon should also be performed to determine the extent of the process.

Tactical approaches to dysplasia lesions in patients with chronic colitis continue to evolve. If the area of the mucous membrane with dysplastic changes is large, has an uneven surface, or is combined with a stricture, surgical treatment is required. However, a typical type of adenoma that has developed in an area of the colon with signs of chronic colitis should be removed with the collection of biopsy material from adjacent areas of the mucous membrane. If the adenomatous polyp is removed entirely and there are no signs of dysplasia in the surrounding mucous membrane, we can assume that adequate treatment has been carried out for a benign sporadic adenoma and continue to monitor the patient with repeated endoscopic examinations.

It remains unclear how many pieces and in what location should be harvested in chronic diarrhea and endoscopically normal colon. The diagnosis of microscopic colitis is established after identifying the corresponding histological signs in patients with chronic watery diarrhea, in the presence of a normal endoscopic picture and the absence of dysbiosis. Biopsy fragments obtained by flexible fiber optic sigmoidoscopy may be adequate to diagnose this condition.

Treatment

The only treatment for benign stomach tumors is surgery. Conservative methods are ineffective. Surgery may be postponed if the tumor is small and there is no risk of malignancy. But in most cases, surgical removal is indicated - with the help of modern technologies, the operation is safe. Early removal is especially important in cases where it is not possible to reliably determine the nature of the tumor - malignant neoplasms must be removed at an early stage.

There are several methods for removing benign tumors that are currently used:

- Endoscopic electroexcision is the name of a minimally invasive operation that involves electrocoagulation through endoscopic access. Polyps are removed in this way.

- Enucleation – allows to reduce blood loss, performed through endoscopic or laparoscopic access (depending on the location of the formation).

- Laparoscopic gastrectomy is an operation with access through punctures of the anterior abdominal wall and an incision in the stomach wall, in which part of the stomach is removed and then a continuous digestive tract is restored using a hardware suture.

- Gastrectomy – complete removal of the stomach. Practically not used for benign tumors.

Endoscopic surgery is indicated when polyps are detected that are visible during diagnosis and are located singly. If the polyp is small, coagulation is sufficient. For neoplasms larger than 5 mm, electroexcision is used - the polyp is pulled by the stalk and then removed with an electrocoagulator. For larger polyps, submucosal resection of the formation is performed (through an endoscope).

Gastric resection is performed in cases of multiple polyps or a high risk of malignancy. Gastrectomy is performed in some cases of diffuse polyposis.

At the CELT clinic you can undergo an examination and begin treatment - modern technologies guard good health.

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) are considered rare mesenchymal neoplasms, the primary incidence is estimated at 7 to 20 cases per 1 million people per year.

However, among malignant submucosal formations of the gastrointestinal tract, GISTs are the most common. The disease is usually diagnosed in patients over 60 years of age, without pronounced sexual dimorphism. GISTs can be found throughout the entire digestive tract, most often in the stomach (50–60%) or small intestine (25–35%), and can also occur in the colon (<7%) or rectum (<5%) , very rarely in the esophagus (1%). There are primary GISTs localized outside the hollow organs, for example in the omentum or retroperitoneal space [1, 2]. Histological variants of GIST are spindle cell (70%), epithelioid cell (20%) or mixed types (10%). Cellular polymorphism, areas of sclerosis and hyalinosis (sclerosing type), and myxoid transformation of the stroma may be present. Palisade-like and hypercellular subtypes occur; the former, as a rule, is detected in GIST along the small intestine, the latter is often accompanied by high mitotic activity [3].

Previously, it was believed that GISTs originate from gastrointestinal stromal cells, but it has now been established that GISTs develop from interstitial cells of Cajal, as a result of oncogenic mutations in the receptor tyrosine kinase ( KIT

) or in platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFR-α).

KIT

mutations , 5–10% of patients have PDGFR-α mutations, while

KIT

and PDGFR-α mutations are mutually exclusive.

KIT

mutations are most often localized in exons 11 (70%) and 9 (10%), less often in exons 13 (1%) or 17 (1%).

PDGFR-α mutations are located in exons 18 (5%), 12 (1%), or 14 (<1%). GISTs with PDGFR-α mutations most often originate from the stomach (90–93%). There are also wild-type GISTs (12–15%), without mutations in the KIT

and PDGFR-α receptors, which can be classified into groups depending on the presence or absence of succinate dehydrogenase (SDH) deficiency.

The SDH deficiency group includes the Carney triad and Carney-Stratakis syndrome, the group without SDH deficiency includes neurofibromatosis type 1 and GIST with BRAF

-,

KRAS

-,

PIK3CA -

mutations. Wild-type GIST is considered to have a lower potential for malignancy [4–6].

Our services

The administration of CELT JSC regularly updates the price list posted on the clinic’s website. However, in order to avoid possible misunderstandings, we ask you to clarify the cost of services by phone: +7

| Service name | Price in rubles |

| Appointment with a surgical doctor (primary, for complex programs) | 3 000 |

| Fluoroscopy and radiography of the stomach | 4 800 |

| Gastroscopy (videoesophagogastroduodenoscopy) | 6 000 |

All services

Make an appointment through the application or by calling +7 +7 We work every day:

- Monday—Friday: 8.00—20.00

- Saturday: 8.00–18.00

- Sunday is a day off

The nearest metro and MCC stations to the clinic:

- Highway of Enthusiasts or Perovo

- Partisan

- Enthusiast Highway

Driving directions

What method is used to remove large polyps?

To remove giant formations en bloc, the dissection method in the submucosal layer is used. The operation is performed under general anesthesia and may take several hours. Afterwards, the hospital stay takes from one to three days.

!!! Regardless of which method was chosen to remove the polyp, after extraction it is sent for histological examination in order to determine the nature of the neoplasm and exclude oncology.

The probability of relapse (re-appearance) of hyperplastic polyps in the stomach is quite high, while in the colon such phenomena are isolated.