Materials and methods

The results of X-ray studies of the upper digestive tract of 116 patients aged 55 to 92 years (average 82 years) examined for dyspeptic syndrome were subjected to a retrospective analysis. Sex ratio M:F 1:4. Group 1 included 83 patients in whom the study was carried out using a regular barium suspension. Their duodenal diameters were measured in 3 places: distal to the bulb (zone A), at the transition point of the second part to the third (zone B) and in the fourth part (zone C). In addition, the length of different duodenal contractions was measured. Group 2 included 8 patients whose X-ray examination was performed with an acidic barium suspension. To do this, 3 g of vitamin C was added to 200 ml of a standard suspension of barium sulfate. The 3rd group included 25 patients aged 69 years to 91 years (on average 85 years), in whom primary diverticula of the duodenum were found during X-ray examination. Group 4 included radiographs from 35 articles on superior mesenteric artery syndrome (SMAS), published in 1990–2014. Studies of the stomach and duodenum with a contrast agent, as well as sections of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at the level of the aortomesenteric angle, were selected for analysis. The distance from the line of sharp contraction in the third part of the duodenum to the location of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was measured. In order to calculate the true value of this distance, the projection distortion coefficient “k” was determined. On radiographs of the abdominal cavity, it is equal to the ratio of the true height of LIII to the height of its image on the radiograph. The true height of LIII in adults is 2.5 cm. When analyzing a computed tomogram, “k” is equal to the ratio of the true diameter of the abdominal aorta to its image on the CT scan. We considered the abdominal aorta diameter to be 2 cm as normal for adults.

When conducting statistical analysis, descriptive statistics methods were used; The arithmetic mean (M) and the error of the mean (m) were calculated. The significance of differences in mean values was assessed using Student's t test. The difference was considered significant at p<0.05.

Symptoms of the disease

Depending on the form of the disease, the following symptoms may be observed:

- pain in the upper abdomen, especially when hungry and at night;

- digestive disorders (diarrhea, constipation);

- bloating, rumbling, flatulence;

- “bitter” belching, incessant hiccups;

- nausea, rarely - vomiting;

- heartburn, discomfort.

In very rare cases, bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract occurs, which is associated with the formation of ulcerations of the mucous membrane.

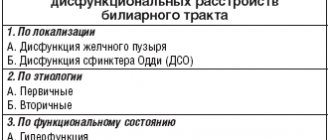

results

In all studies, two zones of narrowing were determined: contracted or opened PS and BDS (Fig. 1). Between the stomach and the duodenal bulb, a contraction zone of the PS, 0.75 cm long, is determined, which regulates the evacuation of chyme from the stomach. The contrast agent did not penetrate distal to the bulb due to contraction of the BJ. The width of the base of the bulb is equal to the width of the antrum of the stomach facing it.

Rice. 1. Sight radiograph of the gastroduodenal junction.

In 47 (56%) cases of group 1, no other sphincters were found in the duodenum. In cases where there was no tight filling of the duodenum with a contrast agent, the lacunae of the folds of the mucous membrane, smeared with barium, created a feathery relief. The width of different sections ranged from 1.2 to 4 cm. The widest was zone B, the less wide was zone A, and the narrowest was zone B (see table). During fluoroscopy, the barium suspension quickly and without delay entered the jejunum.

Width of different sections of the duodenum and length of sphincters, cm

In 16 observations, a narrowing was detected in the second part of the duodenum at a distance of 2-3 cm caudal to the apex of the bulb, but always cranial to the middle of the second part, where SO is usually localized. In this place, instead of a feathery pattern, 2-3 lines parallel to the intestinal wall were identified. Their length ranged from 1 to 3 cm (on average 2.05±0.09 cm) (Fig. 2). In all cases, this narrowing was localized in the same place, i.e., it was not related to peristaltic contraction.

Rice. 2. Simultaneous contraction of the Kapandji (1) and Ochsner (2) sphincters.

A second narrowing was found in 20 cases. It was located in the third part of the duodenum in projection LIII and was most often shifted to the left of the midline. In 2 cases, it represented the X-ray negative distance between the barium-containing sections of the duodenum (see Fig. 2). In 10 patients, instead of a feathery pattern, parallel folds of the mucous membrane are visible in this area. The length of the narrowing ranged from 2 to 4.2 cm (average 3.2 ± 0.15 cm). In 8 cases, it was not possible to measure the narrowing, since only the proximal edge of the narrowing was differentiated, over which the contrast agent stopped above the contracted zone was concentrated.

In 4 of 8 patients of group 2, after taking an acidified barium suspension, contraction zones in the duodenum were not always recorded and quickly disappeared. The X-ray picture did not differ from that in patients of group 1. Noteworthy was the slow evacuation from the duodenum due to the pendulum-like movement of barium between the sphincters. In 4 (50%) patients, the contraction in the third part of the duodenum turned out to be so strong and prolonged that it resembled that during SVBA (Fig. 3). However, during the study, the contraction zone disappeared without a trace.

Rice. 3. Radiographs of the gastroduodenal zone after taking barium with vitamin C. a - contraction of the Ochsner sphincter; b — pendulum-like movement of the contrast agent between the sphincters of Kapandzhi (1) and Ochsner (2).

In patients of the 3rd group, the width of the duodenum is significantly smaller in zones A and B compared to that in patients of the 1st group. The width of zone B was the same in both groups (see table). In almost all patients of group 3, diverticula were located in the descending and horizontal parts of the duodenum (Fig. 4). One patient had multiple diverticula: including in the stomach, 5 diverticula of different sizes in the duodenum, and at least one diverticulum in the jejunum. In one case, the diverticulum was located in the ascending part of the duodenum [5].

Rice. 4. Diverticulum in the descending part of the duodenum between the sphincters of Kapandzhi (1) and Ochsner (2).

On 23 direct radiographs (group 4) with contrast of the duodenum, we measured the distance between the sharply interrupted border of the dilated duodenum and the level of the SMA, if it was recorded on CT, MRI or midline LIII. This distance ranged from 2.5 to 4.6 cm (average 3.30 ± 0.15 cm). In 13 cases, a sharp narrowing of the duodenum began to the right of the right edge of the vertebra (Fig. 5, a, b). In 3 cases, it was possible to measure the length of the entire narrowed segment of the duodenum, since the contrast agent was located both cranially and caudally from it (see Fig. 5, c, d). Taking into account all research methods, in at least 29 (83%) of 35 patients with SVBA described in the literature, the length of duodenal contraction averaged 3.30±0.15 cm and only in 6 (17%) patients the length narrowing in the duodenum was within 1 cm.

Rice. 5. Radiographs of patients with SVBA. a — sharp compression of the duodenum occurred to the right of the right contour of the third lumbar vertebra (white arrow), a black arrow indicates ulcerative deformation of the duodenal bulb [6]; b — the distance between the compressed wall of the duodenum and the midline of the spine, where the aortomesenteric angle is located, is 4.6 cm (white arrow), the height of the third lumbar vertebra (black arrow) is 2.5 cm [7]; c — a black arrow indicates a radio-negative distance of 5 cm in length between the barium-contrasted proximal dilated part and the normal width of the abducens colon, the white arrow indicates the location of the SMA [8]; d - X-ray negative distance between the contrasted segments of the third part of the duodenum, corresponding to the narrow segment, is equal to the height of the third lumbar vertebra, i.e. 2.5 cm [9].

Discussion

Although there are no anatomical sphincters in the duodenum, the presence of BDS is beyond doubt. It appears in every X-ray examination during the filling of the bulb with a contrast agent. Its role is to close the bulb at the moment when it is filled with a certain volume of chyme. When the BDS contracts, the pressure in the bulb increases, which leads to a contraction of the PS [10]. Thus, the BDS is responsible for the portioned evacuation of chyme from the stomach. The lack of anatomical representation of smooth muscle sphincters is not the exception, but the rule. At best, we can talk about thickening of the circular muscle layer (lower esophageal sphincter, PS, colon sphincters, internal anal sphincter).

The present study confirmed the presence of 2 more sphincters. In the descending part of the duodenum there is a Kapandji sphincter with a length of 2.05 ± 0.09 cm. Unlike textbooks, in which it is described either in the middle of the descending part or 2-10 cm below the nipple, in our study it was always located in the proximal parts of the descending department. In cases where the discovery of the Kapandji sphincter was combined with parapapillary diverticula, it was clearly located proximal to the papilla of Vater. In the horizontal part of the duodenum there is an Ochsner sphincter with a length of 3.2 ± 0.15 cm. We received confirmation of our assumption that the sphincters of Kapandzhi and Ochsner are manifested by contraction in response to irritation of the intestine with acidic chyme. The rapid movement of barium into the jejunum, as described in textbooks, is due to the absence of hydrochloric acid in the barium slurry. The role of these sphincters is to prevent low pH chyme from entering the jejunum. These data allowed us to present the motor function of the duodenum as follows.

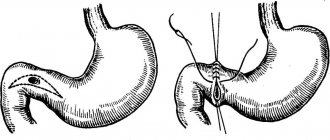

Hypothesis of the motor function of the duodenum. As we showed earlier [11], the PS opens in response to an increase in pressure in the antrum of the stomach to a certain threshold level. The mechanism of PS opening is reflexive in nature [10]. In this case, the circular muscle fibers relax, and the longitudinal fibers, both superficial and deep, originating in the wall of the antrum and attached to the wall of the bulb, contract. During their contraction, they, like parachute lines, stretch the base of the duodenal bulb. The wall of the antrum facing the bulb is stretched to the same extent. The wider the base of the bulb, the wider the “shoulders” of the antrum located opposite. These fibers pass through the wall of the PS and therefore, during contraction, concentrically stretch it, creating a channel for the passage of the bolus (Fig. 6).

Rice. 6. Scheme of PS operation. a — after the bulb is emptied, the PS is in a closed state; b - a strong peristaltic wave laces up part of the antrum, creating at some point a closed cavity.

Continuing to move towards the PS, the wave creates a threshold pressure at which the reflex opening of the PS occurs. This is accompanied by relaxation of circular fibers and contraction of longitudinal groups of muscle fibers.

As soon as the bulb is filled with a certain volume, the BDS reflexively contracts, which leads to an increase in pressure in the bulb and a reduction in P.S. This mechanism is responsible for the portioned evacuation of chyme from the stomach into the duodenum. Acidic chyme, acting on the mucous membrane of the duodenum, causes a double reaction: contraction of the Ochsner and Kapandzhi sphincters, as well as the release of secretin and cholecystokinin by the duodenal epithelium, which regulate the volume and rate of secretion of bile and pancreatic juice depending on their need. Contraction of the Ochsner sphincter stops the bolus and throws it proximally, where it encounters the contraction of the Kapandji sphincter. This creates a pendulum-like movement of the bolus in the chamber between these two sphincters. Bile and pancreatic juice enter the same chamber through the nipple of Vater. Thanks to the contractions of the sphincters, the chyme is mixed with digestive juices, and when the pH of the chyme rises to a certain level, the Ochsner sphincter opens, allowing the bolus to pass into the jejunum. The area of the duodenum between the sphincters, i.e. zone B, is wider than other sections, because it acts as a chamber in which the acidic bolus is mixed with digestive juices. The role of S.O. - ensure a portioned supply of bile and pancreatic enzymes into the duodenum and prevent the reflux of duodenal contents into the bile and pancreatic ducts.

This hypothesis allows us to take a new look at the pathogenesis of duodenal diseases.

Pathogenesis of SVBA. According to our studies, in at least 29 (83%) of 35 patients with SVBA, the length of duodenal contraction is on average 3.30±0.15 cm, which cannot in any way be a consequence of the pressure of the SMA, the diameter of which is 0.5 cm Most often, the contraction zone begins to the right of LIII, i.e., a few centimeters from the location of the SMA, and therefore cannot have any relation to it. At the same time, in terms of length and location, this contraction zone completely corresponds to the Ochsner sphincter - 3.20±0.15 (p>0.2) (Fig. 7). Moreover, this zone behaves like a sphincter. With a sharp increase in pressure in front of the narrowing zone, it opens in such a way as if there was no narrowing at all [12]. We assume that the cause of SVBA in most patients is dyskinesia of the Ochsner sphincter.

Rice. 7. Scheme of anatomical relationships in most patients with SVBA. A narrowing zone in the area of the aortomesenteric angle is identified.

The etiological factors of SVBA (significant weight loss in the catabolic stage, severe injuries, burns, malignant tumors, peptic ulcers, as well as conditions after severe operations) are a necessary trigger that triggers dyskinesia of the Ochsner sphincter. It is easy to see that the listed diagnoses are severe stress factors. It can be assumed that their effect is due to a sharp decrease in the pH of gastric juice, characteristic of a stressful state [13]. A decrease in the aortomesenteric angle is a consequence of a serious condition accompanied by weight loss, and not the cause of the disease. In 6 (17%) patients with SVBA, the length of the narrowed area was about 1 cm.

Diverticula of the duodenum. Primary diverticula are actually acquired pseudodiverticula that occur most often in old age. As a result of increased intraduodenal pressure, prolapse of the mucous membrane occurs through a weak point in the wall of the muscular layer, where the mesenteric vessels usually enter [14, 15]. A manometric study of patients with juxtapapillary (parapapillary) diverticula of the duodenum revealed a significant increase in basal and phase pressure compared to those in patients without diverticula [16]. Such cases are accompanied not only by an increase in pressure in the duodenum, but also by an expansion of more than 10 mm of the common bile duct [17]. Other authors found a decrease in CO tone in juxtapapillary diverticula and suggested that the reflux of bacteria from the duodenum into the bile ducts could play a major role in the occurrence of stones in patients with diverticula, and in duodenopancreatic reflux cause damage to the pancreas [18]. Other authors provide similar studies. Most of them believe that the cause of SO dysfunction is the mechanical pressure of the diverticulum on it [16, 17, 19].

In our study (group 3), almost all primary diverticula were located between the Kapandji and Ochsner sphincters. In addition, we found that the width of zones A and B in patients with primary diverticula was significantly smaller than in patients without diverticula. These data indicate an increase in duodenal tone, especially between the two sphincters, and confirm the importance of dyskinesia of the Kapandji and Ochsner sphincters in the pathogenesis of both diverticula and SO dyskinesia.

Diseases of the pancreatobiliary zone. The cause of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction (SOD) is unknown. In all studies, the majority of patients with DSO were post-cholecystectomy patients. After surgery, complaints of pain in the right hypochondrium are reported by 1 to 1.5% of patients, and in the group of selected patients with postcholecystectomy symptoms - 14% [20]. The frequency of DSO according to manometry varies depending on the type of dyskinesia from 12 to 95% [20]. The conducted studies allow us to assume that the cause of DSO may be high acidity of gastric juice. It leads to an increase in the tone of the Ochsner and Kapandzhi sphincters. As a result, the pressure in the duodenum between them increases, which promotes the reflux of duodenal contents into the bile ducts [5, 21].

Thus, dyskinesia of the duodenum, accompanied by a periodic increase in pressure in the duodenum between the two sphincters into which CO flows, causes tension in this sphincter. In order to conduct bile and pancreatic juice into a chamber with relatively high pressure, the sphincter must work in an enhanced mode. This can initially cause an increase in its tone, and over time its weakness. In both cases, moments arise that facilitate the penetration of duodenal contents into the ducts. In case of SO dyskinesia with high pressure, the frequency of retrograde peristalsis may prevail over antegrade peristalsis [22, 23] and in such cases, SO itself can pass duodenal contents into the ducts.

Diseases of the duodenum

Duodenum

- this is the initial section of the small intestine, which is anatomically connected not only with the stomach, but also with the liver and pancreas through the ducts of Oddi entering through the sphincter of Oddi. Therefore, on the one hand, diseases of the duodenum may have their “roots” in disruption of the functioning of different parts of the digestive tract; on the other hand, diseases of the duodenum may affect other organs of the gastrointestinal tract. Accordingly, good results in the treatment of diseases of the duodenum make it possible to prevent dysfunction and problems of the organs concerned. Currently, gastroenterologists note a significant “rejuvenation” of patients with diseases of the duodenum and an increase in the prevalence of these diseases among schoolchildren.

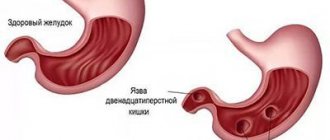

Duodenal ulcer.

Duodenal ulcer is a disease that is caused by a combination of many etiological factors, while the morphological manifestation of the disease is an ulcer - a defect in the duodenal mucosa. Localization of ulcers in the duodenum is more common than in the stomach.

The cause of the ulcer can be psycho-emotional stress, stress, irregular diet, alcohol abuse, smoking. But, basically, the development of the disease is predetermined by internal factors: heredity, metabolic disorders in the body, pathological neuro-humoral regulation of gastric secretion, age-related changes in hormonal levels. Peptic ulcer is a serious and complex disease that often occurs with the development of various complications, such as perforation, bleeding, development of cicatricial narrowing of the outlet of the stomach with disruption of food passage. Classic signs of duodenal ulcer are the seasonality of exacerbations and the daily rhythm of pain. The seasonality of exacerbations (spring, autumn) is explained by changes in the state of the body at different periods of the year, hormonal levels, and neuroendocrine changes. Typically, pain increases on an empty stomach and at night. The pain often decreases after eating or drinking cold milk. Heartburn is also a concern, vomiting and belching occur periodically. Vomiting sometimes occurs at the height of pain and relieves it. If vomiting begins to occur regularly and in large quantities with an admixture of undigested food with a rotten smell, then in this case we may be talking about the development of a narrowing of the lumen of the duodenum due to scar changes in it. The most serious complications of peptic ulcer disease are bleeding, which can be obvious or hidden, and perforation of the ulcer. Bleeding may include bloody vomiting and tarry stools. Perforation of the ulcer causes acute pain and leads to the development of peritonitis.

Duodenitis.

Duodenitis is an inflammatory disease of the mucous membrane of the duodenum. The manifestations of duodenitis visible during endoscopy are swelling and hyperemia (redness) of the mucous membrane; as the disease progresses, erosions appear. If exposure to disease-causing factors continues, ulcers may develop from erosion. The reasons for the development of duodenitis are stress, irregular diet, alcohol abuse, smoking, as well as diseases of other internal organs - liver, gallbladder, pancreas, colitis with impaired intestinal motility. Duodenitis may develop if you are allergic to certain foods. Symptoms of duodenitis: pain in the upper abdomen, nausea, gas formation, feeling of fullness in the stomach, fatigue, lack of appetite, unpleasant taste in the mouth.

Polyps.

Polyps are benign growths of the mucous membrane in the form of formations of various sizes and shapes protruding into the lumen. Small polyps are not felt in any way, large ones (more than 2 cm) can interfere with the passage of food through the duodenum, which causes bloating, nausea and vomiting. The danger of polyps is that they can change their structure over time, even to the point of developing cancer. Therefore, when polyps are detected, regular monitoring with biopsies is necessary.

Tumors.

Tumors of the duodenum are rare. Usually these are tumors of the duodenal papilla - both benign and malignant, or the germination of tumor tissue from nearby organs - the pancreas or intestines. Symptoms of duodenal tumors are weakness, sweating, nausea, vomiting, weight loss, pain in the upper abdomen; with a tumor of the duodenal papilla, pain in the right hypochondrium. All of the above-described diseases of the duodenum are detected by endoscopy, and polyps are treated with endoscopic polypectomy (if the polyp is no more than 1 cm in size).

AT THE FAMILY CLINIC, fibrogastroduodenoscopy and endoscopic removal of polyps of the stomach and duodenum are performed using modern high-quality equipment by experienced endoscopists. If necessary, endoscopic procedures and operations can be performed under general anesthesia.