What is fulminant hepatitis?

The main characteristic of the disease is lightning-fast development and rapid progression of the pathological process.

The development of the disease is based on massive necrosis of hepatocytes (liver cells), which is accompanied by toxic damage to the central nervous system. If signs of severe organ failure are observed two weeks after the onset of icteric syndrome, it is worth talking about the fulminant course of the disease. The occurrence of complications after a month and a half is regarded as a subfulminant form of pathology.

The fulminant form of hepatitis is a serious illness that requires immediate medical attention. Death can occur within several days.

In childhood, the acute course of the disease in most cases is associated with infection of the child after a blood transfusion. In this case, infection occurs with mutated types of pathogens that are highly resistant. The rapid death of hepatocytes is accompanied by increasing liver failure and coma.

The pathogenesis of hepatitis development may also be due to the synthesis of a large number of protective antibodies that damage the liver.

ACUTE VIRAL HEPATITIS

Acute viral hepatitis (AVH) constitutes a group of the most common liver diseases. Every year, 1–2 million deaths from acute respiratory viral infections are recorded worldwide.

Acute viral hepatitis can act as an independent nosological form (hepatitis A, B, C, D, E, F) and as a “companion” of a general viral infection (herpes, adenovirus, infection caused by the Epstein-Barr virus, etc.).

According to the mechanism of infection, the biological characteristics of the pathogens and the nature of the course, acute viral hepatitis can be divided into two groups.

The first group is OVG with an enteral (fecal-oral) mechanism of infection. The main routes of transmission are water, food, and household contact. The causative agents in these cases are non-enveloped viruses: hepatitis A virus (HAV), hepatitis E virus (HEV) and presumably hepatitis F virus (HFV). AVG with an enteral mechanism of infection is resolved without the formation of virus carriage.

The second group is OVG with a parenteral mechanism of infection. The causative agents of this type of hepatitis - hepatitis viruses B, C, D, G (respectively, HBV, HCV, HDV, HGV) - have an envelope. A feature of the course of the disease is the tendency to persistence of viruses and the development of chronic liver damage.

Before moving on to a consideration of the characteristics of acute infection with the hepatitis A virus, it is advisable to briefly consider some clinical features inherent in all acute viral hepatitis.

The clinical picture of OVH is characterized by a wide range of manifestations. However, the following main types of the course of OVH can be distinguished: self-limiting, fulminant (fulminant), cholestatic, recurrent (Fig. 1).

| Figure 1. Dynamics of clinical manifestations in OVH |

Self-limiting (cyclic) type of OVG flow. The severity of the disease varies from subclinical to severe forms. Regardless of the etiology of the disease, it typically begins with a prodromal period, during which the patient develops nonspecific general (asthenia) and gastrointestinal (decreased appetite, nausea, vomiting, pain in the right hypochondrium, stool changes) symptoms; Flu-like symptoms may occur. In rare cases, a syndrome similar to serum sickness develops (skin rashes, arthralgia, symmetrical arthropathy, polymyositis). The duration of the prodromal period is 7–10 days. It should be noted that in the vast majority of cases, the occurrence of symptoms of the prodromal period due to its non-specificity is not associated by either the patient or the doctor with developing AHF, and changes in the patient’s condition are regarded as an acute respiratory disease, influenza, foodborne illness or fatigue.

The severity of prodromal phenomena decreases with the development of the icteric period (the period at the height of the disease), in which the phases of increase, maximum development and decrease of jaundice are distinguished. The appearance of jaundice is preceded by darkening of the urine. During the increasing phase of jaundice, transient skin itching may occur. During this period, the patient’s general well-being usually improves, and the severity of asthenia decreases. On examination, a moderately enlarged, painful liver is revealed; an intermittent sign is an enlargement of the spleen and lymph nodes of the posterior cervical group. The duration of the icteric period ranges from 1–2 days to several months (on average 2–6 weeks).

Starting from the acute period of infection, the patient may manifest a variety of extrahepatic manifestations of immunocomplex origin (skin rashes, arthralgia, chronic membranous glomerulonephritis, nodular arteritis, myocarditis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, essential mixed cryoglobulinemia). Perhaps their development is also due to changes in the functions of mononuclear phagocytes.

In some cases, even at the height of the disease, it can proceed smoothly, without jaundice and a noticeable change in the color of urine and feces. Therefore, even during this period, OVG may remain unrecognized.

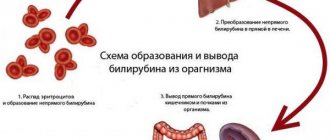

In the blood, an increase in the activity of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartic aminotransferase (AST) by 10–100 times, as well as an increase in the concentration of bilirubin by 2–10 times is detected (the quantitative ratio of “total bilirubin / direct bilirubin” is close to that in obstructive jaundice, which reflects development of intracellular cholestasis).

No significant relationship was found between the degree of increase in serum transaminase activity and the severity of liver damage.

The severity of the course of AVH largely reflects not so much the severity of hyperbilirubinemia as the duration of the icteric period.

Alkaline phosphatase levels, prothrombin index, and serum albumin levels usually remain within normal limits. Leukopenia is observed with or without the development of relative lymphocytosis.

Histological changes in the liver at the height of OVH include: hydropic balloon degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, apoptotic bodies similar to Councilman's bodies, endophlebitis of the central venules, mononuclear infiltration of the portal tracts (cytotoxic lymphocytes and natural killer cells predominate in the infiltrate) with segmental destruction of the terminal plates and parenchyma of the lobules. Kupffer cells are enlarged and contain lipofuscin and cellular debris.

The convalescence phase lasts 2–12 months and is accompanied by residual asthenovegetative and dyspeptic manifestations. In this phase, new formation of connective tissue occurs in the portal and periportal zones of the acinus over several months.

In the absence of normalization of clinical and laboratory parameters within 3 months, the disease is regarded as “protracted acute respiratory syndrome”.

Fulminant hepatitis. This course reflects acute massive lysis of infected cells with accelerated elimination of the virus against the background of excessive activation of the immune system. Development time: 2–8 weeks from the onset of OVH. Data on the risk of developing a fulminant course of AVG depending on the etiology are presented in the table.

The clinical picture is characterized by a rapid increase in signs of liver failure (jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, coagulopathy, ascites, anasarca), the development of multiple organ failure (adult respiratory distress syndrome, hypotension, cardiac arrhythmias, hepato-renal syndrome). During dynamic examination, a decrease in the size of the liver is noted.

Laboratory tests reveal severe coagulopathy, leukocytosis, hyponatremia, hypokalemia, hypoglycemia. Bilirubin and transaminase levels are significantly elevated. With repeated studies, transaminase levels may decrease to normal, despite the progression of the disease.

Liver biopsy in fulminant hepatitis is rarely performed due to the presence of a contraindication - severe coagulopathy. The histological picture was studied on autopsy material; in such cases, massive areas of parenchymal necrosis (with total involvement of the acinus) and collapse of the reticular stroma are revealed.

The mortality rate for this form of acute respiratory syndrome is about 60%. The main causes of death are cerebral and pulmonary edema and massive gastrointestinal bleeding.

Cholestatic hepatitis. This variant of the course is most typical for infection caused by HAV. A characteristic clinical symptom is severe jaundice, which persists for 2–5 months and is accompanied by itching and fever. Some patients experience a long period of decreased or complete lack of appetite and diarrhea.

Characterized by a significant increase in the levels of bilirubin (up to 20 times) and alkaline phosphatase in the blood. Transaminase levels are moderately elevated and can reach normal values in the presence of persistent cholestasis.

Histological examination of the liver reveals degeneration and necrosis of hepatocytes, inflammatory infiltration, the same as in self-limiting hepatitis, a large number of bile cylinders in dilated bile canaliculi, accumulation of bilirubin granules in hepatocytes and their pseudogranular transformation. The prognosis for this form of hepatitis is usually favorable.

Recurrent hepatitis. The main etiological factor in this clinical form of HAV is HAV.

Against the background of resolution of acute hepatitis or after clinical recovery, the patient re-appears clinical and laboratory signs observed in the acute period, including immunologically mediated extrahepatic manifestations (see above). Histological features correspond to those of self-limiting hepatitis. The disease ends in recovery.

It seems that pathological conditions such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, aplastic anemia, and panmyelophthisis may be pathogenetically associated with previous OVH.

In the case of the development of OVH against the background of an existing chronic liver disease, severe decompensation of liver function may be observed. If the reasons for a sharp deterioration in the condition of a patient with chronic liver pathology, an increase in the level of transaminases and bilirubin are unclear, the addition of OVH should be suspected.

General principles of treatment for OVH

With a self-limiting course, hospitalization of the patient is not necessary if he does not have repeated vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea (which can lead to dehydration and disturbances in electrolyte metabolism), and also if those caring for the patient at home are able to provide the necessary sanitary and anti-epidemic measures. During the entire period of the course of OVH, periodic medical monitoring of the patient’s condition is necessary for timely recognition of the fulminant form of the course.

The patient should be provided with sufficient calorie food and fluid intake in the required volume. There is no need to adhere to strict dietary requirements. In the acute phase of the disease, alcohol consumption is contraindicated. It is advisable to avoid intense or prolonged physical activity. The degree of physical and mental activity is largely determined by the patient’s well-being.

No specific methods of drug therapy have been developed. In some cases, according to indications, antiemetics, antispasmodics, analgesics are prescribed, and in case of dehydration, infusion therapy is carried out (intravenous administration of glucose solution). Corticosteroids, due to the risk of increasing the incidence of chronic infection, are not indicated.

In cases of OVH C and OVH G, antiviral therapy is indicated to reduce the risk of developing a chronic infection.

If signs of fulminant hepatitis develop, urgent hospitalization of the patient is necessary, if possible in hepatology centers where liver transplantation is possible. The clinic monitors the patient’s condition, monitors pH, electrolyte and glucose levels in the blood, monitors central venous and intracranial pressure, carries out measures to maintain vital functions and treat complications. In particular, mannitol is prescribed for the progression of cerebral edema, antibiotics to suppress intestinal microflora and treat infectious complications. In the absence of positive dynamics, the patient is prepared for liver transplantation.

In case of cholestatic variant of the course, in order to reduce the severity of skin itching and accelerate the resolution of cholestasis, treatment is carried out with prednisolone (30 mg/day for 3 weeks) or ursodeoxycholic acid preparations. It is possible to prescribe cholestyramine and antihistamines.

Recommendations for the management of a patient with recurrent hepatitis are similar to those given for a self-limiting course of the disease.

Acute viral hepatitis A

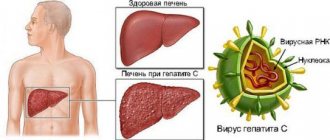

Pathogen. HAV is a non-enveloped RNA virus from the group Picornaviridae (subclass Hepatovirus), 27–30 nm in diameter, with cubic symmetry (Fig. 2). The capsid proteins form 60 centromeres. A single-stranded linear RNA molecule encodes the structure of capsid proteins, P2, P3 proteases and RNA polymerase. One serotype and several genotypes of HAV have been identified.

| Figure 2. Schematic representation of the structure of the hepatitis A virus |

Epidemiology. The source of infection is the patient with OVH A.

The virus is released from the patient’s body within 1–2 weeks in the pre-icteric period and at least 1 week in the icteric period.

HAV is highly stable in the external environment.

The mechanism of transmission of infection is predominantly fecal-oral. The number of cases of infection by parenteral (through blood transfusion from an infected donor) and sexual (in homosexuals, considered as fecal-oral) route is small. The possibility of airborne transmission cannot be completely ruled out. Vertical transmission of the virus (from mother to fetus) has not been established.

Susceptibility to infection is high. Incidence rates vary significantly between regions. In Eastern European countries, it averages 250 cases per 100 thousand population per year. In northern latitudes, the incidence rate is seasonal, with an increase in the autumn-winter period. AHS A is recorded sporadically, in the form of outbreaks or epidemics, which occur every 4–5 years in developing countries.

The main risk factors for the development of OHS A: overcrowding, poor hygiene, travel abroad, contact with a sick person at home, homosexual contacts, contacts with children from kindergartens, drug addiction.

The incubation period is an average of 30 (15–50) days.

Pathogenesis. From the gastrointestinal tract the virus enters the liver. Virions replicate in the cytoplasm of the hepatocyte and are released into the bile (Fig. 3).

| Figure 3. HAV replication in liver cells |

Hepatocyte lysis is mediated by the immune response to infection with the participation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes and/or the mechanism of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. HAV is not expected to have significant direct cytopathogenicity.

Clinical picture. A subclinical course, often under the guise of acute gastroenteritis, is usually (up to 90% of cases) observed in children. In adults, OVH A usually occurs in a manifest form.

In the prodromal period, fever is possible (up to 39° C). With the appearance of jaundice, an improvement in well-being is noted.

In the acute period, a measles-like or urticaria-like skin rash may be observed. In general, the incidence of extrahepatic manifestations is significantly lower than with OVH B or C.

In the convalescence phase, a small number of patients develop transient ascites, which is not an unfavorable prognostic sign, as well as transient proteinuria and hematuria. The origin of these symptoms is unknown.

For OVH A, the most typical development is cholestatic forms with painful skin itching. Relapses are observed more often than with other OVH, especially in childhood. They develop 30–90 days after the onset of the disease, which is believed to be associated with re-infection or reactivation of the primary infection. The pattern of relapse resembles that of the first attack, with repeated release of the virus. Relapses end in recovery and are rarely accompanied by arthritis, vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemia. The development of relapse can be predicted by the absence of a trend towards a decrease in serum ALT levels.

Serological diagnosis. In the blood, stool, and duodenal contents in the acute period, HAV antigen (HAAg) can be detected using an immunofluorescence reaction, complement fixation method, radioimmune method or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). However, these techniques have not found widespread use in clinical practice.

The most accessible methods of virological diagnosis are the detection of antibodies of the IgM and IgG classes to the virus.

Anti-HAV class IgM, highly specific for HAV A, can be detected in the blood serum throughout the entire acute phase of the disease and the next 3–6 months (up to 1 year in low titer).

Anti-HAV IgG class, in all likelihood, provides lasting immunity and persists throughout life after suffering from HAV A.

Course and prognosis. The average duration of the disease is 6 weeks. As a rule, patients recover without special treatment.

The probability of death does not exceed 0.001%.

No chronic infection is observed. Liver function and histology usually return to normal within 6 months.

| Table Risk of developing acute liver failure in acute viral hepatitis |

Among the complications, the development of mesangioproliferative glomerulonephritis with nephrotic syndrome has been described. There is evidence of the triggering role of OVH A in the development of autoimmune hepatitis type I in individuals with impaired function of suppressor T-lymphocytes.

Prevention. Nonspecific methods of prevention include isolation of patients and persons in contact with them during the last 2 weeks of the pre-icteric period and 1 week of the icteric period, disinfection of objects used by the patient, hand washing, and appropriate cooking of food during illness.

Preventive measures before contact with a patient (prevention with a “delayed effect”) include active immunization with an inactivated HAV vaccine.

Vaccination is indicated for residents of areas with low and medium incidence rates, people at risk: those traveling to endemic areas; patients who are frequently injected with medications; children and young people living in overcrowded conditions; military personnel; patients with chronic liver diseases; laboratory workers exposed to HAV; homosexuals; sometimes - to employees of child care institutions and food industry enterprises.

Dosage regimen: adults over 19 years of age - administration of the vaccine in two stages according to 1440 Elisa Units (EU) with a break of 6-12 months. Children over 2 years old are vaccinated using a three-stage regimen - 360 EU with an interval of 1 and 6-12 months - or a two-stage regimen - 720 EU with an interval of 6-12 months.

A single vaccination provides immunity for 1 year, repeated (“boosting”) vaccination for 5-10 years.

The preventive effectiveness of the vaccine is 95–100%. Immunogenicity is very high: in almost 100% of healthy patients, the vaccine causes the production of anti-HAV (in 85% of vaccinated people - within 15 days). Tolerability is good. There is no danger of infecting others after vaccination.

The administration of a live attenuated vaccine is also an effective way to prevent HCV A, but it has not yet found widespread use.

| Figure 4. Changes in serological parameters in OVH A |

Preventive measures after contact with a patient (prevention with an “immediate effect”) involve passive immunization with serum immunoglobulin. Indications for its implementation: intra-family and close contacts with a patient with AVG A (immunizes, including infants). Do not use for random sporadic contacts outside the home. Immunization of large groups is justified when there is a real risk of epidemics.

Immunoglobulin dosage regimen: 0.02 ml/kg body weight is injected into the deltoid muscle no later than 14 days after contact with the patient.

The method can also be used for rapid immunization of persons traveling to endemic areas, but at a higher dose - 0.06 ml/kg body weight (it is advisable to first determine the presence of anti-HAV in the patient's blood).

If the tense epidemiological situation continues, repeated immunization is possible.

The effectiveness of passive immunization in preventing clinically manifest forms of AVH A is 100% when administered before exposure and 80–90% when administered within six days after exposure. Tolerability of immunoglobulin is assessed as good.

Simultaneous active and passive vaccination with contralateral administration is possible (when traveling to endemic areas), as well as simultaneous active vaccination against hepatitis A and B.

Yu.O. Shulpekova, Candidate of Medical Sciences MMA named after. I. M. Sechenova, Moscow

For questions regarding literature, please contact the editor.

Etiology

The fulminant course of hepatitis can be a consequence of both infection of the body and toxic damage to the liver by exogenous factors.

The leading cause of the disease is infection (viral hepatitis type HBV in combination with type D, HCV and HAV are less common). The provoking factor of the disease can also be cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex or Epstein-Barr.

HBV infection preceding the disease is recorded in only 1% of cases in newborns up to six months. As for non-infectious causes, fulminant hepatitis develops due to:

toxic effects of alcohol (including surrogates), phosphorus or mushroom poisons;- overdose of hepatotoxic drugs. These include drugs that are used in the treatment of tuberculosis, tetracycline antibiotics and some inhalational anesthetics for anesthesia;

- traumatic liver injury, including during surgery;

- hypo- and hyperthermia;

- local circulation disorders due to vascular pathology;

- acute cardiac failure;

- failure of the immune system.

Separately, it should be said about the cryptogenic form of hepatitis. The disease in this case develops for a reason that cannot be determined. This situation is not so rare and is observed in 30% of patients.

Chance of getting sick

In areas with a high prevalence of HBV, the virus is most often transmitted from mother to child during childbirth or from person to person in early childhood. Transmission of infection during the perinatal period or early childhood can also lead to the development of chronic infections in more than one third of those infected.

Hepatitis B is also spread through cutaneous or mucosal exposure to infected blood or various body fluids, as well as through saliva, menstrual, vaginal secretions and seminal fluid. Sexual transmission of hepatitis B can occur.

Transmission of the virus can also occur through the reuse of syringes and needles, either in health care settings or among injection drug users. In addition, infection may occur during medical, surgical or dental procedures, tattooing, or the use of razor blades or similar objects contaminated with infected blood.

Despite the fact that Russia is a country with a moderate rate of hepatitis B infection, the risk of becoming infected with this virus throughout life for each of us is 20-60%.

Clinical manifestations

In order to promptly suspect a disease, you need to know its clinical symptoms, which can occur at lightning speed:

- signs of intoxication (hyperthermia, headache, body aches, malaise). At the onset of the disease, the fever reaches 39 degrees. The person moves little, becomes lethargic, drowsy, and has periodic attacks of aggression. A child of the first year of life is capricious, constantly cries and screams, which indicates the development of the disease;

- dyspeptic disorders in the form of nausea. Vomiting is initially provoked by taking medication, food or water, and then occurs spontaneously. It may contain an admixture of blood, which is why it visually resembles “coffee grounds”;

- pain in the area of the right hypochondrium;

- the smell of fresh liver from the mouth and from feces;

As the pathology progresses, the leading symptom of liver damage appears – jaundice. It develops far from the onset of the disease, which makes early diagnosis difficult. The skin and mucous membranes gradually acquire a yellowish tint, which indicates the height of the pathology. Further signs of the disease include:

- speech disorder. She becomes slow and slurred;

- inhibition of actions;

- change in psycho-emotional state (a person becomes indifferent);

- monotony of voice. He loses his emotional coloring;

- intestinal dysfunction in the form of diarrhea;

- dysuric disorders (urinary retention).

The liver gradually decreases in size and acquires a softer consistency. As the organ “dries out,” the signs of intoxication intensify. Clinical symptoms depend on the stage of hepatitis:

- initial period;

- precoma, the development of which is caused by progressive necrosis of hepatocytes;

- coma is a consequence of decompensating liver failure.

The severe stage of hepatitis is accompanied by an increase in heart rate, a decrease in blood pressure, the appearance of shortness of breath, a decrease in daily diuresis (urine volume), as well as the appearance of signs of a disorder of consciousness.

Symptoms

The incubation period for hepatitis B lasts on average 75 days, but can increase to 180 days. The virus can be detected 30-60 days after infection.

During the acute infection stage, most people do not experience any symptoms. However, for some, acute hepatitis B infection may cause symptoms that last several weeks, including yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), dark urine, extreme tiredness, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. A relatively small number of patients with acute hepatitis may develop acute liver failure, often leading to death (fulminant hepatitis).

In some people, the hepatitis B virus can also cause a chronic liver infection that can later develop into cirrhosis or liver cancer.

Complications after an illness

Hepatitis B is dangerous because of its consequences: it is one of the main causes of liver cirrhosis and the main cause of hepatocellular cancer of the liver. The likelihood that hepatitis B virus infection will become chronic depends on the age at which a person acquires the infection. Children most likely to develop chronic infections are those infected before the age of six:

- chronic infections develop in 80-90% of children infected during the first year of life;

- Chronic infections develop in 30-50% of children infected before the age of six.

- 15-25% of adults who become chronically infected during childhood die from liver cancer or cirrhosis.

Among adults:

- Chronic infections occur in <5% of infected, otherwise healthy adults;

- 20%-30% of chronically infected adults develop cirrhosis and/or liver cancer.

The probability of complete recovery from chronic hepatitis B is very low - about 10%. But a state of relative health (remission), in which the virus practically does not bother the patient, can be achieved in more than 80% of cases.

Diagnostics

There are certain criteria that allow you to make a diagnosis of fulminant hepatitis. They include signs of hepatic coma, as well as massive death of gland cells. In this case, the severity of jaundice is not an indicator of the severity of the disease, because with a malignant course it does not reach its peak. Precursors of pathology include:

- increasing severity of the patient's condition;

- change in psycho-emotional state (lethargy is replaced by euphoria, excitement and attacks of aggression);

- an increase, then a decrease in the severity of pain in the hepatic zone, which is due to a change in the volume of the gland;

- increase in fever up to 40 degrees;

- signs of hemorrhagic syndrome (hemorrhages, spider veins);

- liver odor;

- respiratory distress and fluctuations in blood pressure as signs of cerebral edema;

- decrease in daily urine volume.

To confirm the diagnosis, laboratory and instrumental research is required.

Laboratory methods

Laboratory diagnostics include the following methods:

general clinical analysis - prescribed to assess the severity of neutrophilic leukocytosis;- examination of feces, where a decrease in the content of stercobilin, discoloration of feces and signs of impaired digestion of lipids and carbohydrates are recorded;

- urinalysis, in which an increased content of urobilinogen is observed;

- biochemistry - determines the level of bilirubin, iron and ferritin. Usually these indicators are elevated. In addition, the doctor is interested in the content of liver enzymes (ALT, AST) and alkaline phosphatase, which are often increased. In the terminal stage, the quantitative composition of transaminases may decrease. The tests also reveal a deficiency of albumin and prothrombin;

- markers of viral hepatitis - necessary to confirm or exclude infectious liver damage.

Instrumental research

Using instrumental diagnostic methods, it is possible to visualize the liver and assess the condition of the surrounding internal organs. To do this, the doctor prescribes an ultrasound, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging or biopsy (rarely performed).

Histological analysis reveals a low content of Kupffer cells in the material.

With widespread necrosis, the destructive process covers the entire area of the hepatic lobule, preserving the functioning of only a few peripheral cells.

One of the signs of a relatively favorable prognosis is the detection of submassive necrosis. It is characterized by limitation of destruction to only the central part of the lobule.

During the diagnosis, an “empty hypochondrium” is detected, which indicates a decrease in liver volume. The organ becomes flabby, and there is practically no zone of dullness.

Symptoms

No symptom is specific for the fulminant form of autoimmune hepatitis. The onset of the disease is characterized by the following clinical signs:

- severe malaise;

- drowsiness;

- pain in the liver area;

- yellowness of the skin and mucous membranes;

- discoloration of feces;

- darkening of urine;

- fever;

- body aches (muscle, joint pain);

- skin itching;

- menstrual irregularities;

- hemorrhages;

- rapid cardiac contractions.

Signs of complications associated with damage to large joints gradually appear. Apart from pain, no other symptoms are observed with polyarthritis, including no deformation of the musculoskeletal structures.

There are also signs of ulcerative damage to the intestinal mucosa, cardiac dysfunction, pericarditis, thyroiditis, diabetes, glomerulonephritis and Cushing's syndrome.

Possible complications

A serious complication of the disease is hepatic coma. Its development is based on massive necrosis of hepatocytes. It is also accompanied by:

- cerebral edema followed by progressive respiratory and cardiovascular disorders. Thus, the level of oxygen in the blood decreases (hypoxia) and the content of carbon dioxide increases (hypercapnia). Symptomatically, the pathological condition is manifested by intense headache, facial flushing, vomiting without relief, rapid breathing, cardiac arrhythmia, arterial hypertension and signs of damage to the nervous system;

- massive bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract, which is caused by disruption of the coagulation system;

- renal failure. Due to the narrowing of blood vessels, the delivery of nutrients and oxygen to the kidneys is disrupted, resulting in their dysfunction. This is manifested by a decrease in the rate of diuresis, a decrease in urine concentration, thirst, dry mucous membranes and an increase in the level of urea, creatinine and residual nitrogen in the blood;

- a generalized infection, which occurs due to a decrease in the body’s immune defense. This could be a new infection or an exacerbation of chronic bacterial diseases.

Treatment

The patient is prescribed strict bed rest. Permission to get out of bed is given exclusively by a doctor based on the results of laboratory tests and the severity of clinical symptoms.

Treatment of a malignant form of hepatitis is carried out in a special box, where the patient is isolated from others. In such conditions he remains until the end of the icteric period.

Medication assistance

Urgent actions include:

high doses of hormonal medications;- interferons;

- ensuring airway patency. According to indications, tracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation may be performed;

- bladder catheterization – necessary to control diuresis;

- gastric lavage - to stop the absorption of poison if it enters the body through the gastrointestinal tract;

- sedatives (GHB, diazepam - to combat psychomotor agitation);

- heart rate and blood pressure monitoring;

- infusion therapy (glucose, polyglucin, trisol, amino acids - hepasol, aminosteril);

- antibacterial agents;

- diuretics (manitol);

- fresh frozen plasma, platelet mass;

- antacids.

In order to reduce the severity of intoxication, the use of efferent methods of therapy is indicated. This may be hemosorption or plasmapheresis. If drug therapy is ineffective and complications progress, surgical intervention (liver transplantation) is indicated.

Diet therapy

In the acute phase of the disease, replenishment of energy costs is carried out using parenteral solutions. As the condition improves, tube feeding may be prescribed. Subsequently, the patient is transferred to an oral diet subject to strict restrictions. They concern semi-finished products, fatty dishes from fish and meat products, as well as hot seasonings, coffee, fresh baked goods, sweets, smoked meats and sour vegetables.

Effectiveness of vaccination

As of 2013, 183 Member States were vaccinating infants against hepatitis B as part of their national vaccination schedules, and 81% of children had received hepatitis B vaccination. This represents significant progress compared to 31 countries in 1992, when the World Assembly Health Council adopted a resolution recommending global vaccination against hepatitis B.

Additionally, as of 2013, 93 Member States have introduced hepatitis B dose provision at birth. Since 1982, more than one billion vaccine doses have been used worldwide.

In many countries where typically 8% to 15% of children had chronic hepatitis B virus infection, vaccination has reduced rates of chronic infection among immunized children to less than 1%.

Forecast

The high mortality rate in fulminant hepatitis is due to the rapid progression of the disease and the insufficient effectiveness of drug therapy.

To avoid the development of this form of the disease, you should adhere to the following recommendations:

- use protective equipment when in contact with poisons;

- visit only trusted beauty salons;

- use barrier contraception (condoms) during casual intimacy;

- have personal hygiene products;

- undergo regular examinations to identify infectious pathogens.

As for newborns, prevention consists of timely immunization of infants and a full examination of future parents at the stage of pregnancy planning.

Vaccines

Expert opinion

CM. Harit

Professor, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Head of the Department of Prevention of Infectious Diseases, Research Institute of Children's Infections

Hepatitis B is contracted everywhere equally through blood (everyone) and through sexual contact (teenagers and adults). A drop of blood is so small that you cannot see it and it is already contagious, so families become infected through toothbrushes, razors, etc...

The basis for preventing hepatitis B is vaccination. WHO recommends that all infants should receive hepatitis B vaccine as soon as possible after birth, preferably within 24 hours. If a child does not receive this vaccination in the maternity hospital, the risk of infection increases significantly, and if a newborn is infected during the neonatal period, liver cirrhosis develops in adolescence or early adulthood.

The dose given at birth should be followed by two or three subsequent doses to complete the vaccination series. In most cases, one of the following two options is considered optimal:

- A three-dose hepatitis B vaccination regimen, in which the first dose (of monovalent vaccine) is given at birth and the second at 1 month of age, which is also very important, since this dose minimizes the risk of infection of the child from infected family members. The third dose (of monovalent or combination vaccine) is administered at 6 months, simultaneously with the DTP vaccine, which determines the duration of immunity against hepatitis B.

- A four-dose regimen in which the first dose of monovalent vaccine given at birth is followed by 3 doses of monovalent or combination vaccine, usually given along with other vaccines as part of routine childhood immunization, is indicated for children born to mothers infected or with hepatitis B.

After a full series of vaccinations, more than 95% of infants, children of other age groups and young adults develop protective antibody levels. Protection lasts for at least 20 years and possibly a lifetime.

More about vaccines