Diseases of the operated stomach (OSG) are essentially iatrogenic diseases, since they are a consequence of surgical intervention, which dramatically changes the anatomical and physiological relationships and interconnections of the digestive organs.

Depending on the nature of the operation performed, two types of postoperative disorders are distinguished: postgastroresection and postvagotomy. Over the past two decades, the ratio of post-gastroresection and post-vagotomy disorders has changed, which reflects the views of surgeons on the tactics of treating complicated and uncomplicated gastroduodenal ulcers. Thus, in the early 90s, selective proximal vagotomy was considered the main method of surgical treatment of peptic ulcers, which was performed for both complicated and uncomplicated ulcers.

Currently, due to the increased possibilities of pharmacotherapy of gastroduodenal ulcers, a sharp decrease in relapses of the disease after eradication of H. pylori, patients with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease practically do not undergo surgery. Vagotomy as an independent method of choice retained its importance only in a small group of complicated gastroduodenal ulcers. Due to this, as well as the fact that operations (resections) for gastric cancer have become more frequent, modern doctors are more likely to encounter post-gastroresection disorders: dumping syndrome, hypoglycemic syndrome, afferent loop syndrome, peptic ulcer of the anastomosis, post-gastroresection dystrophy, post-gastroresection anemia.

Definition

Diseases of the operated stomach are a consequence of surgical intervention, which dramatically changes the anatomical and physiological relationships and relationships of the digestive organs, and also disrupts the neurohumoral interactions of the digestive tract with other internal organs and systems.

Depending on the nature of the operation performed, two types of postoperative disorders are distinguished: postgastroresection and postvagotomy.

The clinical variations of these disorders are closely related to the type of surgery performed. Therefore, in each specific case, you need to clearly know what kind of surgery was performed on the patient.

What are the main types of gastric surgery?

Gastric resection. There are three main types of gastrectomy: Billroth I, Billroth II (Fig. 1) and Roux-en-Y. All other proposed operations are their modification.

Vagotomy. Vagotomy can be performed at different levels of the n.vagus: trunk, proximal, selective proximal vagotomy.

Drainage operations. Vagotomy is often accompanied by drainage operations. With truncal vagotomy, gastroenteroanastomosis is most often performed. With selective proximal vagotomy, which is usually performed for pyloroduodenal stenosis, pyloroplasty is performed.

Radiation damage to the intestines

Radiation damage to the intestine manifests itself in the form of colitis, an inflammatory disease of the intestinal mucosa. Colitis predominantly develops in patients receiving therapy in the pelvic area (uterus, cervical canal, prostate, rectum, bladder).

Colitis can occur at any stage of treatment: during the start of radiation therapy and within 3 months after the end of treatment. There are also late-delayed radiation colitis, which occur during the first year after radiation therapy.

Symptoms

The main symptoms of radiation damage to the intestines include: disturbance of stool, diarrhea, false urge to defecate, pain along the intestines and pain in the anus, depending on the area where the patient receives radiation therapy. With sufficiently severe inflammation, the following symptoms appear: fecal and gas incontinence, dyspepsia, flatulence, vomiting, nausea, weight loss due to diarrhea.

If at the beginning of radiation therapy, during it, or after it, the patient experiences bleeding with stool, you should immediately consult a doctor! He will prescribe the necessary examinations and treatment.

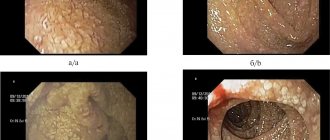

Diagnosis of radiation damage to the intestine

Studies that allow you to determine the extent of damage and prescribe therapy:

- Collection of complaints and anamnesis

- Laboratory research

- FCS - fibrocolonoscopy (used for late-delayed colitis)

- Anoscopy (used for early lesions, allows you to assess the degree of inflammatory reaction of the rectum)

- CT/MRI

- Irrigoscopy

- Fistulography (used only in the presence of a fistula, to determine the fistula tract; this is not a routine study.

Epidemiology

After almost every operation on the stomach and duodenum, functional and organic disorders can be detected. Clinically significant disorders are observed in 30–35% of patients who underwent gastrectomy, and in 15–34% who underwent vagotomy.

In patients operated on for peptic ulcers, dumping syndrome and peptic ulcers of the anastomosis are more common; in patients operated on for gastric cancer, post-gastroresection dystrophy and anemia are more common.

Currently, due to the increased possibilities of pharmacotherapy for gastroduodenal ulcers and, above all, a sharp decrease in relapses of the disease after eradication of H. pylori, patients with uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease practically do not undergo surgery. Vagotomy as a method of choice has retained its importance only for complicated gastroduodenal ulcers.

Abnormal bowel movements during treatment (diarrhea/constipation)

Diarrhea

The main factors that cause diarrhea (therapy is selected depending on them):

- chemotherapy

- carrying out radiation therapy

- gastrectomy (removal of the stomach)

- enzyme deficiency

- impaired absorption of macro and microelements after extensive resections of the small intestine

- hypoalbuminemia (low production of the protein albumin can lead to intestinal swelling)

- infectious diarrhea due to decreased immunity during antitumor therapy

- bacterial overgrowth syndrome (especially worsened after surgical treatment and during chemoradiotherapy)

- taking antibiotics

- development of pseudomembranous colitis

Any of the above symptoms requires contacting a doctor to prescribe therapy.

If, against the background of diarrhea, the patient experiences a rise in temperature or intoxication, then additional examination for pseudomembranous colitis is necessary.

Diarrhea and fecal incontinence

After operations on organs located in the pelvis, the patient may experience a combination of two syndromes at once - diarrhea and fecal incontinence. Most often, this disorder is observed in gynecological patients.

The patient may experience unformed or half-formed stools, as well as fragmented bowel movements during the day, difficulties in holding feces and gases after the urge to defecate. Sometimes there is nocturnal fecal incontinence.

To assess the condition of the anal sphincter, specialists prescribe sphincterometry.

When treating pathology, a combination of methods is used - drug therapy, physiotherapy, exercise.

Constipation/stool retention

The symptom may be accompanied by complaints such as tension and/or pain in the abdomen, straining, bloating, hard stool, a feeling of incomplete bowel movement, the need for manual assistance during bowel movement, lack of urge to defecate, or false urge to defecate without bowel movement.

Causes of constipation/stool retention may include:

- chemotherapy

- carrying out radiation therapy

- surgery

- adhesive disease

- carcinomatosis

- worsening of diseases already present before the diagnosis of cancer

If the patient experiences constipation or stool retention, consultation with a specialist is necessary.

Diagnostic methods that will help determine the cause of constipation:

- fibrocolonoscopy

- Anasphincterometry (allows you to study the tone of the pelvic floor muscles and the tone of the anal sphincter)

- fluoroscopy

- plain radiograph of the abdominal cavity

- laboratory tests (stool cultures, etc.)

If, during treatment, stool retention lasts more than 4 days, and increased gas formation, nausea and/or vomiting, and pain in the intestines are noted, then urgent consultation with a specialist is necessary!

Therapy for constipation/stool retention

The traditional method of treatment is drug therapy. In case of adhesions, surgical treatment may be required.

Please note that pain therapy may worsen the situation.

Etiology and pathogenesis

The development of food intake is based on various disorders of the anatomical and physiological activity of the digestive organs. There are a number of general prerequisites for the emergence of food and drink.

A significant pathogenetic factor in the development of gastrointestinal tract is the nature of the operation performed (volume and method of gastric resection, selectivity and completeness of vagotomy) and the disease for which the patient was operated on, as well as concomitant diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, which can reduce the compensatory capabilities of the body and create favorable conditions for the development of lifestyle. The previous state of the diffuse neuroendocrine system is of great importance, primarily the level of gastrointestinal hormones (cholecystokinin, motilin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, enkephalins, etc.) that regulate the activity of the gastrointestinal tract. You should also take into account genetic factors and environmental influences (family relationships, bad habits, eating habits and lifestyle), which may affect the ability to adapt to new conditions.

Diagnostics

The diagnosis of ABD is made on the basis of a comprehensive analysis of the clinical picture, the results of X-ray and endoscopic examinations, as well as recording of laboratory data. The significance of these methods for establishing certain types of food safety standards is ambiguous. Diagnosis of dumping syndrome, hypoglycemic syndrome, post-vagotomy diarrhea, as a rule, is based on characteristic clinical symptoms; X-ray examination plays a leading role in identifying adductor syndrome, gastrostasis and dysphagia after vagotomy, and endoscopy for peptic ulcers.

Characteristics of certain types of diseases of the operated stomach. Postgastroresection syndromes

Dumping syndrome occupies a leading place among post-resection disorders. It occurs, according to various authors, in 3.5–38% of patients who underwent gastric resection according to Billroth II. The difference in statistical indicators is due to the lack of common views on the essence of the syndrome. The pathogenesis of dumping syndrome is complex. In its development, the main importance is attached to the accelerated evacuation of stomach contents and the rapid passage of food masses through the small intestine.

The entry of hyperosmolar food into the small intestine leads to a number of disorders:

- an increase in osmotic pressure in the intestine with the diffusion of fluid into its lumen and, as a consequence, a decrease in bcc;

- rapid absorption of carbohydrates, which stimulate excess insulin secretion, which first causes hyperglycemia and then hypoglycemia;

- irritation of the receptor apparatus of the small intestine, leading to stimulation of the release of biologically active substances (acetylcholine, kinins, histamine, etc.), an increase in the level of gastrointestinal hormones (secretin, cholecystokinin, motilin, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide, etc.).

The clinical picture of dumping syndrome includes a vasomotor component (weakness, sweating, palpitations, pallor or flushing of the face, drowsiness, increased blood pressure, dizziness, and sometimes fainting) and a gastrointestinal component (heaviness and discomfort in the epigastric region, rumbling in the abdomen, diarrhea, as well as nausea, vomiting, belching and other dyspeptic phenomena). These phenomena occur during a meal or 5–20 minutes after it, especially after eating sweet and dairy foods. The duration of attacks ranges from 10 minutes to several hours.

Based on the severity, it is customary to distinguish between mild, moderate and severe dumping syndrome.

Mild dumping syndrome is characterized by episodic, short-term attacks of weakness that occur after eating sweet and dairy foods. The patient's general condition is quite satisfactory, his performance does not decrease.

With dumping syndrome of moderate severity, pronounced vasomotor and intestinal disturbances occur after eating any food, especially sweet and dairy dishes, as a result of which the patient is forced to take a horizontal position. Performance decreases.

In severe dumping syndrome, almost every meal is accompanied by a pronounced and prolonged attack of weakness, dizziness or fainting. Working capacity sharply decreases, the patient becomes disabled.

Diagnosing dumping syndrome in the presence of characteristic symptoms does not cause difficulties. The rapid evacuation of barium suspension (“discharge”) from the gastric stump and accelerated passage through the small intestine, revealed by X-ray examination, and the characteristic glycemic curve after a carbohydrate load confirm the diagnosis.

Hypoglycemic syndrome (HS) is also known as late dumping syndrome and is essentially its continuation. HS occurs in 5–10% of patients.

It is believed that as a result of accelerated emptying of the stomach stump, a large amount of carbohydrates ready for absorption immediately enters the jejunum. The blood sugar level quickly and sharply rises, hyperglycemia causes a response from the humoral regulation system with excessive release of insulin. An increase in the amount of insulin leads to a drop in sugar concentration and the development of hypoglycemia.

Diagnosis of HS is based on the characteristic clinical picture. The syndrome is manifested by a painful feeling of hunger, spastic pain in the epigastrium, weakness, increased sweating, feeling of heat, palpitations, dizziness, darkening of the eyes, trembling of the whole body, and sometimes loss of consciousness. The attack occurs 2–3 hours after eating and lasts from several minutes to 1.5–2 hours.

The glycemic curve after a glucose load in most patients is characterized by a rapid and steep rise and an equally sharp drop in blood sugar concentration below the initial level.

HS is often combined with dumping syndrome, but can also be observed in isolation.

Afferent loop syndrome (ALS) occurs in 3–29% of cases after gastric resection according to Billroth II due to impaired evacuation of duodenal contents and the entry of part of the eaten food into the afferent loop of the jejunum rather than into the afferent loop.

SPP is divided into:

- functional, arising as a result of dyskinesia of the duodenum, adductor loop, sphincter of Oddi, gall bladder;

- mechanical, caused by an organic obstacle (defect in operating technique, loop bend, adhesions).

Clinically, SPP is manifested by bursting pain in the right hypochondrium shortly after eating, which subsides after fairly profuse vomiting of bile. Sometimes in the epigastric region a distended adductor loop of the jejunum is palpated in the form of an elastic, painless formation that disappears after profuse vomiting of bile. Persistent vomiting can lead to loss of electrolytes, poor digestion, and weight loss.

Diagnosis of SPP is based on X-ray examination. X-ray signs of the syndrome are a long delay of contrast in the afferent loop of the jejunum, a violation of its peristalsis, and expansion of the loop. Due to partial obstruction, radiographic identification of the afferent loop during barium administration is difficult. In these cases, soluble contrast can be administered using a catheter passed through the endoscope channel.

Peptic ulcers (PU) after gastrectomy can form in the anastomosis area from the gastric stump, jejunum or at the site of the anastomosis. PYs develop in 1–3% of operated patients (Kuzin N.M., 1987).

The time frame for the development of PJ in the anastomotic zone ranges from several months to 1–8 years after surgery. Reasons for their formation:

- economical resection;

- left area of the antrum of the stomach with gastrin-producing cells;

- gastrinoma or other endocrine pathology.

Clinical manifestations of PJ anastomosis resemble the symptoms of peptic ulcer disease. However, the disease usually occurs with more severe and persistent pain than before surgery, and complications in the form of bleeding and penetration of the ulcer are not uncommon.

X-ray and endoscopic examinations can confirm the diagnosis. As a rule, ulcers are found at the site of anastomosis, near it from the side of the stomach stump, less often in the efferent loop of the jejunum opposite the anastomosis.

Postgastroresection dystrophy (PD) often occurs after gastrectomy performed using the Billroth II method. Severe metabolic disorders that can be attributed to PD occur in 3–10% of cases (Samsonov M.A. et al., 1984). In their pathogenesis, the leading role is played by indigestion and absorption due to insufficiency of pancreatic secretion and damage to the small intestine. The diagnosis of PD is based primarily on clinical findings. Patients complain of rumbling and bloating, diarrhea. Symptoms of malabsorption are typical: weight loss, signs of hypovitaminosis (skin changes, bleeding gums, brittle nails, hair loss, etc.), cramps in the calf muscles and bone pain caused by disorders of mineral metabolism. The clinical picture can be supplemented by symptoms of damage to the liver, pancreas, as well as mental disorders in the form of hypochondriacal, hysterical and depressive syndromes.

In patients with PD, hypoproteinemia is detected due to a decrease in albumin levels, disturbances in carbohydrate and mineral metabolism.

Postgastroresection anemia (PA) is detected in 10–15% of patients who have undergone gastrectomy. PA comes in two variants:

— hypochromic iron deficiency anemia;

— hyperchromic B12-deficiency anemia.

The cause of iron deficiency anemia in most cases is bleeding from peptic ulcers of the anastomosis and erosions of the mucous membrane during reflux gastritis, which often occur hidden. The development of this variant of anemia is facilitated by impaired ionization and resorption of iron due to accelerated passage through the small intestine and atrophic enteritis. After removal of the stomach, the function of producing internal factor is lost, which sharply reduces the utilization of vitamin B12, as well as folic acid. This is also facilitated by changes in the composition of the intestinal microflora. Deficiency of these vitamins leads to megaloblastic hematopoiesis and the development of hyperchromic anemia.

Differential diagnosis of PA is based on the study of peripheral blood and bone marrow. In the peripheral blood, with iron deficiency anemia, hypochromia of erythrocytes and microcytosis are observed, and with B12-deficiency anemia, hyperchromia and macrocytosis are observed. In a bone marrow smear with pernicious anemia, a megaloblastic type of hematopoiesis is detected.

How often is dumping syndrome observed?

This picture can appear after each meal, but during breakfast it is more pronounced, at lunch it appears a little less, and at dinner even less. Symptoms may last a few minutes or may last up to three hours. This is not all, because the patient also experiences weakness the rest of the time, but not so intense, and over time, asthenia develops, including a decrease in potency.

The frequency of development of dumping syndrome is unknown, in the specialized literature different figures are indicated - from 10 to 80%, it all depends on how focused the team of authors who wrote the article is in treating it. If the authors of the article are involved in the treatment of post-resection complications, then the frequency is high - they specifically collect such patients. If the scientific material was prepared by surgeons, then a full statement of dumping syndrome in operated patients is far from ideal and real; as a rule, only a severe course is monitored.

In most cases, the syndrome is mild with partially blurred clinical signs; a severe course is typical for women who have undergone surgery. Again, it is not really known how many patients there are with a severe syndrome; options range from one to ten per hundred operated on. Some operated patients who experience weakness after eating do not even suspect the presence of mild dumping syndrome, which could be corrected if a diagnosis were made.

Post-vagotomy syndromes

Dysphagia is a complication characteristic of the early postoperative period (appears in the first 2 weeks and disappears on its own after 1–2 months), but can also develop in more distant periods. The incidence of dysphagic disorders after vagotomy is 3–17% of the number of operated patients. The cause of dysphagia in the early postoperative period is trauma and swelling of the esophageal wall. In addition, denervation of the distal esophagus causes temporary dysfunction of the cardia. The development of dysphagia more distant from vagotomy is associated with reflux esophagitis and cicatricial changes in the surgical area.

With mild dysphagia, X-ray and endoscopic methods usually fail to detect any pathological changes in the esophagus. In patients with more severe and persistent dysphagic disorders, dilation and pointed narrowing of the distal segment of the esophagus is detected radiographically, and reflux esophagitis is detected during endoscopic examination.

Gastrostasis can occur after all types of vagotomy. Even after selective proximal vagotomy (SPV), 1.5–10% of operated patients experience delayed gastric emptying. Motor-evacuation disorders of the stomach after vagotomy are of two types: mechanical and functional. Mechanical gastrostasis is caused by obstruction of the gastric outlet in the area of pyloroplasty or gastroenteroanastomosis. Functional gastrostasis occurs due to a disturbance in the rhythm of the peristaltic wave of the stomach, which leads to uncoordinated movements in time and direction and mechanical overstretching of its walls.

Clinically, motor-evacuation disorders of the stomach are manifested by a feeling of fullness in the epigastric region, nausea, and occasional pain. In severe forms of gastrostasis, the patient is bothered by almost constant pain and a feeling of heaviness in the upper abdomen, and profuse vomiting of stagnant gastric contents. Vomiting alleviates the patient's condition, which encourages it to be induced artificially. An X-ray examination reveals retention of the contrast mass in the stomach, sluggish and superficial peristalsis, as well as an increase in the size of the stomach.

Recurrent ulcers after vagotomy, including after PPV, occur in 10–30% of cases. The cause of recurrence of ulcers after vagotomy is usually insufficient denervation of the stomach and persistent high production of HCl. Promotes the occurrence of relapse and impaired evacuation from the stomach.

Diagnosing recurrent ulcers after vagotomy is a difficult task, since in 30–50% of cases they are asymptomatic. Therefore, patients with peptic ulcer who have undergone vagotomy, especially in the first 5 years after surgery, must be examined 2 times a year, alternating endoscopic and radiological examinations.

Diarrhea occupies a prominent place among the complications of vagotomy. Diarrhea most often occurs during stem vagotomy with drainage operations and is associated with abnormally rapid discharge of fluid from the stomach into the small intestine, changes in the composition of the bacterial flora of the small intestine, impaired secretion and absorption of bile acids, which leads to intestinal hypermotility. The occurrence of post-vagotomy diarrhea is also associated with achlorhydria, impaired exocrine function of the pancreas, and atrophic changes in the mucous membrane of the small intestine.

Diarrhea is manifested by loose stools 3–5 times a day. Sometimes diarrhea is provoked by dairy foods and carbohydrates; more often, diarrhea appears unexpectedly, accompanied by large gas formation and a sharp rumbling in the stomach. The urgency of the urge causes significant inconvenience to the patient. Abnormal bowel movements are observed for several days; such cycles can be repeated 1–2 times within a month.

Dumping syndrome after PWS is observed in 2–9% of patients; the use of drainage operations increases its frequency to 10–34%. However, severe forms of the syndrome are observed very rarely (Shalimov A.A. et al., 1986). The pathogenesis of post-vagotomy dumping syndrome is essentially no different from post-resection dumping syndrome: rapid emptying of the stomach, overfilling of the small intestine with food, hyperosmolarity due to the rapid breakdown of polysaccharides and abundant formation in the intestine of biologically active substances that accelerate peristalsis and affect the cardiovascular system.

Diagnosis of post-vagotomy dumping syndrome is not difficult and is based primarily on an analysis of the patient’s complaints.

Clinical picture

Patients are concerned about pain and heaviness in the right hypochondrium, accompanied by vomiting of bile, after which the pain decreases.

In mild cases, these phenomena occur once every 2 weeks, in moderate cases - 2-3 times a week, in severe cases - several times a day, while the amount of bile reaches 500 ml, which causes rapid exhaustion of the patient.

An objective examination can reveal asymmetry of the abdomen due to bulging of the right hypochondrium, which disappears after profuse vomiting. Sometimes there is a slight yellowing of the sclera. X-ray reveals an atonic adductor loop - a barium suspension can remain in it for up to 2 hours.

Prevention and treatment

Prevention of disease of the operated stomach

An important place in the prevention of life-threatening diseases is occupied by strict adherence to indications for surgical treatment, the optimal choice of surgical method and the implementation of technically competent rehabilitation measures. Rehabilitation of patients should be carried out in stages.

During the period of preoperative preparation (stage I), patients with ulcer disease are prescribed antiulcer therapy (diet No. 1, antacids, antisecretory drugs, eradication for HP infection), and for gastric cancer - general restorative measures and symptomatic therapy. All this allows the operation to be performed under more favorable conditions.

In the early postoperative period (stage II), the patient is prescribed fasting for 2 days and active aspiration of gastric contents is performed. Already during this period, enteral nutrition can be administered through a tube. From the 2nd–4th day, if there are no signs of stagnation in the stomach, the patient should adhere to a special diet. The diet is based on the principle of gradually increasing the load on the gastrointestinal tract and including a sufficient amount of protein. It is advisable to use protein enpit as a source of complete and easily assimilated protein. By the end of the 1st week, if the operation failed to achieve a significant reduction in gastric acid production, antacids are prescribed, and, if necessary, H2 receptor blockers or proton pump inhibitors.

Complex therapy, aimed at compensating the functions of various body systems disrupted by the operation, begins 2 weeks after the operation and lasts 2–4 months (stage III). An important part of complex treatment during this period is diet. The Institute of Nutrition of the Academy of Medical Sciences of the Russian Federation has developed a special diet - P (mashed), the purpose of which is to help reduce the inflammatory process in the gastrointestinal tract, activate repair, and also prevent the occurrence of dumping reactions, hypoglycemia, afferent loop syndrome, etc. This is a physiologically complete diet with a high protein content (140 g), normal fat content (110–115 g) and carbohydrates (380 g), with limited mechanical and chemical irritants of the mucous membrane and the receptor apparatus of the gastrointestinal tract. Refractory fats, extractives, easily digestible carbohydrates, and fresh milk are excluded. Patients must follow a regimen of fractional meals. Pharmacotherapy is continued according to indications: antacids, agents that normalize peristalsis (motilium, imodium for diarrhea, duspatalin).

In the future, even if the patient has no signs of illness of the operated stomach, one should adhere to preventive dietary measures for 2–5 years (stage IV): split meals (4–5 times a day), limiting foods and dishes containing easily absorbed carbohydrates, fresh milk. The diet should be quite varied, taking into account individual food intolerances. Patients with a good outcome from surgery usually do not require any drug therapy.

Treatment of disease of the operated stomach

Treatment of gastrointestinal tract can be conservative and surgical. Diet therapy occupies a leading place in the conservative treatment of AD. Food should be varied, high in calories, high in protein, vitamins, normal fat and complex carbohydrates with a sharp limitation of simple carbohydrates. Individual tolerance to foods and dishes should also be taken into account. Patients usually tolerate boiled meat, lean sausage, cutlets made from lean meat, fish dishes, soups with strong meat and fish broths, fermented milk products, vegetable salads and vinaigrettes seasoned with vegetable oil. The most intolerable foods are sugar, milk, sweet tea, coffee, compote, honey, sweet liquid milk porridges, pastries made from butter dough, especially hot ones. Meals should be small, at least 6 times a day.

Such a diet and nutritional regimen is usually acceptable for all types of food intake. However, there are a number of features in their treatment, primarily regarding pharmacotherapy.

In case of dumping syndrome, it is recommended to start eating with hearty dishes; after eating, it is advisable to lie in bed or recline in a chair for 30 minutes. Pharmacotherapy for dumping syndrome should be aimed at the main links in its pathogenesis.

Improving the evacuation of gastric contents is achieved by using prokinetics (Motilium). Imodium (loperamide) is prescribed orally, 1–2 capsules 1–2 times a day. The drug slows down intestinal propulsion and increases sphincter tone. Considering that dumping syndrome often occurs in individuals with certain manifestations of neurovegetative dystonia, patients should be treated with sedatives and tranquilizing drugs. Use small doses of phenobarbital (0.02–0.03 g 3 times a day), benzodiazepine derivatives, infusion of valerian, motherwort. The prescription of peritol (4 mg 3 times a day half an hour before meals) deserves attention.

In general, the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy in patients with dumping syndrome is very low, and therefore reasonable dietary recommendations are more useful.

A feature of the treatment of hypoglycemic syndrome is the need to stop attacks of hypoglycemia. The patient is forced to carry a piece of sugar or crackers with him to relieve the first signs of hypoglycemia. Severe attacks of hypoglycemia are not typical for this syndrome, so the need for intravenous administration of a 40% glucose solution is rare.

To reduce symptoms of impaired evacuation from the afferent loop, patients should be advised to lie on their right side after eating. Along with dietary measures, repeated gastric lavage and drainage of the adductor colon through an endoscope can reduce the manifestations of SSP. To eliminate the inflammatory component and sanitize the blind loop from the microbial flora that has developed in it, antibacterial therapy is indicated. For this purpose, eubiotics (Intetrix 1 tablet 3 times a day), sulfonamides (Sulgin, Bactrim 1 tablet 2–4 times a day) or antibiotics (ampicillin at a dose of 0.5 g 4 times a day intramuscularly, orally - tetracycline) are used in a daily dose of no more than 1,000,000 units, doxycycline (vibramycin) 0.1–0.2 g 1–2 times a day). The course of treatment is 7–14 days.

In case of peptic ulcer of the anastomosis or recurrence of the ulcer after vagotomy, complex antiulcer therapy is prescribed, the principles of which do not differ from that for exacerbation of peptic ulcer disease.

For gastrostasis that occurs early after vagotomy, treatment should begin with suction of the stomach contents through a nasogastric tube. Patients with functional gastrostasis are further advised to limit fluid intake, since dense foods in such cases stimulate peristalsis. Improving the evacuation of gastric contents is also achieved by using prokinetics (Motilium). If therapy is ineffective, bougienage of the anastomosis is indicated.

Imodium (loperamide) orally, 1-2 capsules 1-2 times a day, gives a good therapeutic effect for post-vagotomy diarrhea. The drug slows down intestinal propulsion and increases sphincter tone. To improve digestion, pancreatic enzymes are used; drugs that do not contain bile acids (Creon, pancitrate, mezim forte), as well as drugs that are stable in the acidic environment of the stomach and contain enzymes of non-animal origin (unienzyme with MPS), are better tolerated.

Treatment of malabsorption syndrome with post-gastroresection dystrophy, as well as anemia, is carried out according to generally accepted rules.

If conservative treatment of gastrointestinal tract is futile, the issue of surgical intervention is decided. Indications for surgery are severe dumping syndrome and organic afferent loop syndrome.

Weight loss (malnutrition)

Weight loss in an oncology patient occurs due to many factors: it is necessary to take into account the patient’s treatment now and in the past, the patient’s condition, the volume of surgical interventions, etc.

Causes of weight loss:

- Surgical treatment performed (post-resection syndromes)

- Consequences of the treatment: CT/RT; bowel dysfunction, nausea, vomiting, radiation damage to the mucous membrane, decreased appetite/change in taste.

- Impaired patency/motility of the gastrointestinal tract

- Progression of the underlying disease, chronic pain syndrome.

- Other reasons

Malnutrition assessment

In outpatient practice, various scales are used to assess malnutrition.

The situation assessment should include at least the following questions:

- How much weight did the patient lose from the onset of the disease to the time of his appointment with the gastroenterologist?

- How much of this weight was lost in the last 1-3 months?

- Has the patient taken any nutritional medications?

- What additional therapy does the patient receive?

- Are you currently receiving nutritional supplements? If yes, what dosage and what exactly?

Algorithm for prescribing nutritional support

This algorithm should be developed together with a specialist, since the patient cannot independently select for himself an adequate therapy that will help improve well-being and alleviate symptoms.

For the algorithm for prescribing nutritional support, it is necessary to answer the following questions:

- How many?

To calculate the patient's energy needs, it is necessary to assess the existing malnutrition and the risks of progression of malnutrition.

- How?

The optimal route for administering therapeutic nutrition is selected. The following options are possible: sipping (therapeutic nutrition that the patient can consume independently), tube feeding, combined nutritional support (combining parenteral and enteral nutrition). Separately, it is worth considering situations when the patient has a stoma (gastrostomy, enterostomy, esophagostomy): in this case, the administration of nutritional medications can be carried out through it.

- When?

The feeding regimen and the administration of therapeutic nutritional medications are determined.

- How long?

The timing of nutritional support for the patient is determined.

- How?

The choice of drugs for a specific situation is carried out.

Methods for assessing the effectiveness of nutritional support

- Bioelectrical impedance analysis

- Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

These methods are often used in routine practice. They allow you to assess changes in body composition against the background of nutritional support, assess the volume of fat mass, extracellular and intracellular fluid, and indirectly assess the amount of muscle mass.

- laboratory and instrumental assessment of indicators

- calorimetry

These methods are rarely used in routine practice. However, their advantage is their accessibility - the doctor can assess the body’s condition directly during the appointment.