Quick transition Treatment of gastritis

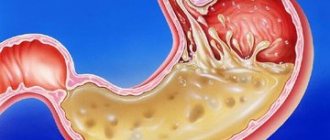

Gastritis is a general term that combines several pathological conditions characterized by inflammation and degeneration of the gastric mucosa.

The mucous membrane covers the entire surface of the stomach and plays an important role in digestion. Its glands produce gastric juice, the enzyme pepsin, hydrochloric acid, lipase, hormone-like components, mucus and bicarbonate. These substances are responsible for the breakdown of proteins and fats, protect the body from pathogenic bacteria, and activate metabolic processes.

When inflamed, the mucous membrane produces less acid, enzymes, mucus and other substances that are necessary for the proper functioning of the gastrointestinal tract. There is a risk of developing gastritis.

Gastritis can occur in acute and chronic forms. It is important to see a doctor in time to get a diagnosis and treatment, and to prevent complications.

Forms and complications of gastritis

In the absence of adequate and timely treatment, gastritis can cause complications. These include:

- Stomach ulcer. Peptic ulcers affecting the mucous membrane of the stomach or duodenum. Peptic ulcer disease is provoked by excessive use of painkillers (NSAIDs), and gastritis caused by H. pylori. It is difficult to say where gastritis ends, especially with erosions, and peptic ulcer disease begins. Apparently these are different forms of the same process.

- Atrophy of the gastric mucosa - atrophic gastritis. It occurs due to thinning of the mucous membrane, the formation of fibrosis (microscars) of the membrane during chronic gastritis. With atrophy, the number of active cells in the gastric mucosa that produce enzymes and acid decreases. The absorption of some vitamins is impaired. Atrophic gastritis is a risk factor for oncological transformation and therefore requires special attention.

- Gastric bleeding with erosive gastritis and ulcers. It is characterized by shortness of breath, weakness, dizziness, blood in the vomit and stool, black stools, and pale skin. If these symptoms occur, you should immediately seek medical help.

- Anemia. Most often it occurs due to acute (as described above) or chronic blood loss, for example, with multiple repeated erosions of the stomach. Research suggests that H. pylori-associated gastritis and autoimmune gastritis can affect the body's absorption of iron and vitamin B12 from food, which can also cause anemia.

- Vitamin B12 deficiency and pernicious anemia (pernicious anemia). Autoimmune gastritis does not produce a certain protein that helps absorb vitamin B12, which is necessary for the production of red blood cells and nerve cells. Insufficient absorption of vitamin B12 can lead to the development of pernicious anemia. The same changes occur in the advanced stage of atrophic gastritis of any origin.

- Stomach cancer. Chronic gastritis increases the likelihood of developing benign or malignant neoplasms in the gastric mucosa. For example, gastritis associated with H. pylory increases the risk of adenocarcinoma and lymphoma of the gastric mucosa.

Symptoms

In general, chronic gastritis is practically asymptomatic; its presence can be suspected during periods of exacerbation (when clinical symptoms reveal themselves most clearly) or during a preventive FGDS study. The clinical picture of each type of chronic gastritis is not fundamentally different. There are “classic” symptoms that allow one to suspect the presence of this pathology. Among the main symptoms, the following should be highlighted: 1) pain in the epigastric region, which can occur both on an empty stomach and after directly eating (or after 1/2-1.5 hours). The pain can be dull, aching, or it can be periodically cutting, cramping. A characteristic feature is a decrease in pain after taking antacid or antisecretory drugs; 2) a feeling of heaviness and discomfort in the epigastric region, a feeling of fullness in the stomach after eating; 3) belching of air or sour, unpleasant taste in the mouth; 4) loss of appetite (typical of gastritis with low acidity); 5) nausea, less often vomiting; 6) unstable stool.

Causes and risk factors of gastritis

- Bacterial infection Helicobacter pylori. It is one of the most common types of infections and is transmitted through the fecal-oral route, for example through contaminated food and water. For the development of gastritis, the presence of Helicobacter pylori infection alone is not enough. It is believed that vulnerability to the bacterium is inherited or occurs due to an unhealthy lifestyle (smoking, poor diet), medications.

- Painkillers (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, NSAIDs). Regular and excessive use of aspirin, ibuprofen or naproxen can cause both acute and chronic gastritis, their toxic effects reduce the production of the main protectors of the gastric mucosa. To distinguish this situation from other types of gastritis, it is called NSAID gastropathy.

- Alcohol. Irritates and gradually destroys the gastric mucosa, exposing it to the aggressive effects of gastric juice. Alcohol most often provokes acute gastritis.

- Age. Older people are at increased risk of developing gastritis because the lining of the stomach thins with age. Older people are also most vulnerable to infections (H. pylori) or autoimmune disorders.

- Stress. Severe stress associated with injuries, burns, severe operations and infections can trigger acute gastritis.

- Exposure to radiation or radiation therapy (due to another medical condition).

- Bile reflux after gastric resection.

- Allergies to foods such as cow's milk and soy (especially in children).

- Autoimmune diseases. As a result of autoimmune processes, the body produces antibodies that attack the cells that form the gastric mucosa. Autoimmune inflammation occurs, and the functions of the protective barrier of the mucous membrane decrease. Gastritis associated with autoimmune disorders is called autoimmune gastritis. It is more common in people with other autoimmune disorders, including Hashimoto's disease and type 1 diabetes. Autoimmune gastritis may also be associated with vitamin B12 deficiency.

- Other diseases. The risk of gastritis may be increased by other medical conditions, including Crohn's disease, sarcoidosis, parasitic infections, and HIV/AIDS.

Diet

- In case of exacerbation of gastritis, a gentle diet is necessary. Patients with gastritis are contraindicated in chocolate, coffee, carbonated drinks, alcohol, canned food, concentrates and substitutes of any products, herbs, spices, as well as fast food products, dishes that provoke fermentation (milk, sour cream, grapes, black bread, etc.) , smoked, fatty and fried foods, pastry products. At the same time, food should be varied and rich in proteins and vitamins.

- After the end of the acute condition, nutrition should become complete, observing the stimulating principle during the period of remission in patients with low acidity. Small meals are recommended, 5-6 times a day.

Stages of gastritis

- Hyperemia. At the first stage of gastritis development, hyperemia (redness) of the gastric mucosa is observed. This is a protective vegetative-vascular reaction - dilation of blood vessels and increased blood flow in response to a negative effect on the mucous membrane. Hyperemia is accompanied by edema, this is a sign of the development of inflammation.

- Chronic inflammation, metaplasia, dysplasia. The production of hydrochloric acid decreases, the mucous membrane thickens. Hypertrophy is typical for people who abuse alcohol. Inflammation is characterized by the accumulation of leukocytes in the stomach wall; prolonged inflammation can change the structure of the gastric epithelium, it can become similar to intestinal epithelium, this phenomenon is called metaplasia and may be associated with an increased risk of cancer. But the risk is especially high if a biopsy reveals a violation of the structure of the tissue and cells of the stomach - dysplasia.

- Atrophy. Prolonged inflammation causes thinning of the gastric mucosa, recovery processes slow down, atrophic changes in the mucosa are observed - epithelial cells die and are replaced by scar tissue.

- Erosion and ulcers are a frequent companion to gastritis. Focal and profound changes develop due to a decrease in the performance of the mucous glands, thinning of the protective layer, in most cases this is a consequence of exposure to H. pylori.

Chronic gastritis with normal and increased secretory function of the stomach

This type of disease is typical for young men. The surface epithelium of the stomach is affected; as a rule, no destruction occurs in the mucous membrane. Patients feel pain similar to that of an ulcer. After eating, they have a feeling of internal heaviness. Patients constantly complain of heartburn and unpleasant belching. The majority of them suffer from constipation. All these phenomena intensify at night.

Treatment of gastritis

Treatment for gastritis depends on the cause. Acute gastritis caused by taking NSAIDs or alcohol abuse does not require drug therapy; it is enough to exclude these triggers.

In other cases, your doctor may recommend:

- Antibiotic therapy against H. pylori.

- Drugs that block the production of hydrochloric acid (a component of gastric juice) and promote healing of the mucous membrane (proton pump inhibitors* - omeprazole, lansoprazole, rabeprazole, esomeprazole, dexlanzoprazole, pantoprazole.

- Antacids** (neutralize stomach acid, relieve pain).

* - Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors, especially at high doses, may increase the risk of hip, wrist and spine fractures, and an osteoporosis prevention program may be required. ** - Side effects - constipation, diarrhea.

Features and advantages of the gastritis treatment method at the Rassvet clinic

Diagnosis and treatment of gastritis at the Rassvet clinic is carried out in the gastroenterology department. We use evidence-based methods based on international clinical guidelines. Your primary treatment will begin only after a physical examination and all necessary tests and diagnostic tests have been completed.

Important. The influence of certain foods or dietary systems on the risk of gastritis has not been proven by research.

At the Rassvet Clinic, we first of all distinguish gastritis from functional dyspepsia. Gastritis is often asymptomatic, but it is necessary to treat it, since it is a slow but sure road to stomach cancer. Functional dyspepsia, on the contrary, is accompanied by many complaints, but endoscopic examination and biopsy do not reveal pathology.

How gastritis is treated at the Rassvet clinic

To clarify the diagnosis, we use the most modern and accurate equipment and logistics methods. For example, we have built a system for diagnosing gastritis and determining cancer risk according to the OLGA classification. Our endoscopes allow you to perform gastroscopy with multiple magnification and examine the mucous membrane through light filters, taking a biopsy from the most suspicious areas. The biopsy samples themselves are also assessed by the histologist using the OLGA scale, and as a result we obtain a figure that reflects the risk of oncological transformation in the coming years. Further treatment tactics depend on the value of this figure.

We value the comfort of patients, so in Rassvet you can undergo an examination under anesthesia in the shortest possible time.

Recommendations from a gastroenterologist at the Rassvet clinic for patients with gastritis

Timely consultation with a doctor and proper treatment will help keep the disease under control. A strict diet is not needed. However, the rules of a healthy diet should be followed - do not overeat, avoid foods that irritate the mucous membranes (smoked, fried, fatty), and give up alcohol. If you are forced to take painkillers that increase the risk of gastritis, check whether they can be replaced with a drug that is less aggressive on the gastric mucosa (acetaminophen, paracetamol).

Author:

Amelicheva Alena Aleksandrovna medical editor

Disease prevention

No one knows 100% how to cure gastritis, but doctors have determined precise recommendations on how to avoid this disease. Rational, nutritious and healthy nutrition; “no” to alcohol and other bad habits; oral hygiene; timely treatment of gastrointestinal diseases; gentle regime; changing jobs if working conditions are associated with hazardous production - these are simple rules that will protect any person from serious consequences. At the first signs of disturbances in the digestive tract, you should consult a doctor. Prompt and competent treatment, including treatment of atrophic gastritis, can be quite effective. Regular examination can generally be considered a sign of a person’s respect for himself and concern for his own health.

Of course, there is a lot of all kinds of literature on how to cure gastritis, and promises from pseudo-specialists to get rid of the disease. But you need to trust only trusted doctors and clinics. Any treatment should take place only under their strict supervision. When the disease subsides, a sanatorium stay is recommended.

Autoimmune gastritis

(AIH) is, as a rule, an asymptomatic disease, most often detected with the progression of atrophy of the gastric mucosa and the development of iron deficiency or B12-deficiency (pernicious) anemia (PA) [1].

For the first time, “an outstanding form of anemia,” later called PA, was described in 1849 by Thomas Addison. In 1860, Flint associated its development with atrophy of the gastric mucosa (GMU). Successful treatment with raw liver suggested that megaloblastic anemia is caused by a deficiency of extrinsic (vitamin B12) and intrinsic Castle factors in gastric juice. In 1960, Schwartz discovered antibodies to intrinsic factor, and in 1962, Irwin discovered antibodies to parietal cells (PC), which indicated the autoimmune nature of atrophic gastritis leading to PA. AIH was described in 1965 by McIntyre et al. in patients with PA in whom histamine-resistant achlorhydria, coolant atrophy and antibodies to intrinsic Castle factor were detected [2]. In 1973, Strickland and Mackay identified two main variants of chronic gastritis - A and B, while gastritis A (autoimmune) was characterized by primary atrophic changes in the mucous membrane of the fundus of the stomach [3].

AIH is a chronic atrophic gastritis, as it progresses, the acid production of the stomach decreases. In AIH, circulating antibodies to PC and intrinsic Castle factor are detected in the blood. There are no exact data on the prevalence of AIH, which determines the relevance of large-scale population studies [4].

AIH is the most common cause of severe vitamin B12 deficiency due to cobalamin malabsorption in older adults. The incidence of vitamin B12 deficiency in AIH varies from 37 to 69% [5], which is likely due to the high heterogeneity of the populations studied and limited access to prospective studies. The prevalence of PA in the general population is about 0.1%, but reaches 2% in people over 60 years of age [1]. One study analyzed blood levels of vitamin B12 in 729 Americans aged ≥60 years and found that 1.9% had undiagnosed and untreated PsA. Its prevalence was 2.7% in women, 1.4% in men, and 4.3 and 4.0% in blacks and Caucasians, respectively [7].

In China, 181 patients with megaloblastic anemia were examined. PA was diagnosed in 61% of cases; atrophy of the gastric glands was detected in 70% of patients according to histological examination. Serum antibodies to intrinsic factor of Castle were more common (73%) than serum antibodies to gastric PC (65%). Antibodies to PC were detected more often in men (78%) than in women (53%; p=0.018) [8].

It should be noted that the absorption of vitamin B12 is affected by taking certain medications (proton pump inhibitors, H2-histamine receptor blockers, metformin). Helicobacter pylori is known to cause chronic active gastritis, and its progression leads to atrophic gastritis [9, 10]. Moreover, H. pylori was detected in 56% of people with vitamin B12 deficiency [11].

Five studies provided data on the prevalence of AIH in patients with iron deficiency. Dickey et al. examined 41 patients with iron deficiency anemia (IDA). Atrophic gastritis, according to histological examination, was found in 8 (20%) patients, and in 6 of them antibodies to Castle factor or PC were detected, in 1 H. pylori was detected [12]. A study by Hershko et al. included 150 patients with IDA of unknown etiology. Antibodies to PC in combination with hypergastrinemia, indicating AIH, were found in 27% of cases [13]. In a British study, 12 of 44 (27%) patients with anemia and iron deficiency had antibodies to PC [14]. Kulnigg-Dabsch et al. when assessing the cause of iron deficiency in 409 patients with or without anemia, antibodies to PC were detected in 18.5% of cases. Moreover, the presence of antibodies was combined with lower levels of hemoglobin and ferritin [15].

Pathogenesis of AIH

Both genetic and environmental (external) factors play a certain role in the development of AIH. In mouse models, AIH susceptibility genes (Gasa 1, 2, 3 and 4) were found on chromosomes 4, 6 and in the H2 region. Interestingly, 3 of these genes are located at the same locus as diabetes mellitus (DM) susceptibility genes, which may explain the association between AIH and type 1 diabetes (T1DM) [16].

In AIH, a mononuclear infiltrate is histologically detected in the coolant, affecting the lamina propria between the gastric glands, which includes plasma cells, T lymphocytes and a large population of non-T cells (probably B cells), resulting in the production of antibodies to proton pump antigens PC and internal factor [1]. Damage to the coolant is the result of indirect destruction of the gastric PC by circulating autoantibodies of the proton pump pump (H+/K+-ATPase). It has been suggested that this unrestricted process also induces progressive loss of chief cells [17]. As a result, PCs of the coolant are replaced by mucous and metaplastic cells of both intestinal and pseudopyloric types. In the later stages of the disease, the gastric mucosa consists of atrophic and metaplastic epithelium.

Several studies have reported that a significant number of patients with H. pylori infection also expressed autoantibodies against H+/K+-ATPase. The presence of these autoantibodies in individuals infected with H. pylori was often associated with higher serum gastrin levels, a lower pepsinogen I/II ratio, and a marked decrease in hydrochloric acid secretion. In addition, it was shown that PA, which was previously considered an exclusive complication of AIH, was accompanied by H. pylori infection. Based on these histological and clinical findings, it is hypothesized that classic AIH may be caused by H. pylori infection. However, these assumptions are based on a relatively small number of clinical studies. In contrast, in a study by Zhang et al., which included 9684 patients, 53% of whom were infected with H. pylori, the association between anti-PC antibodies and chronic atrophic gastritis was higher among patients negative for H. pylori (odds ratio [RR] – 11.3; 95% confidence interval [CI] – 7.5–17.1) than among the positive (OR=2.6, 95% CI – 2.1–3.3). The overall prevalence of anti-PC antibodies was 19.5% [18].

The association of AIH with other autoimmune diseases is well known. Data have been published on the combination of AIH with vitiligo, alopecia, celiac disease, myasthenia gravis and autoimmune hepatitis [18]. Several studies have noted its frequent combination with T1DM [19], as well as with autoimmune polyglandular syndromes (APGS). PA occurs among 10–15% of patients with APGS type I (hypoparathyroidism, Addison's disease, diabetes, and mucosal candidiasis) and in 15% of patients with APGS type III (DM and autoimmune thyroid diseases) [20, 21].

Most often, AIH is combined with autoimmune thyroiditis: more than 50% of patients with AIH have circulating antithyroid peroxidase antibodies [22]. The association between autoimmune thyroid disease and AIH was first described in the early 1960s. More recently, this association has been included in APGS type IIIb, in which autoimmune thyroiditis represents the underlying disease. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is the most common autoimmune disease, it is associated with diseases of the digestive tract in 10–40% of patients, on the other hand, it affects about 40% of patients with AIH. The pathogenesis of these two diseases shows some similarities, including a complex interaction between genetic, embryological, immunological and environmental factors. Despite their different locations and functions, the thyroid gland and stomach have similar morphological and functional characteristics, probably due to their common embryological origin [23]. In fact, the thyroid gland develops from the primitive gut, so its follicular cells are of the same endodermal origin as the PC. In addition, gastric cells and thyroid follicular cells demonstrate the ability to concentrate and transport iodine across the cell membrane [24]. Iodine, in addition to its essential role in the synthesis of thyroid hormones, regulates the proliferation of cells of the coolant. In fact, in the presence of gastric peroxidase, iodine acts as an electron donor and participates in the removal of oxygen free radicals, providing an antioxidant effect. These effects may explain the regulatory role of iodine in cell proliferation of the gastric mucosa and its protective role against carcinogenesis in the stomach. This hypothesis is supported by the association between iodine deficiency, goiter and an increased risk of gastric cancer [25].

The incidence of AIH in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases was assessed in a prospective study that initially included 208 adult patients. 166 of them had Hashimoto's thyroiditis, and 42 had Graves' disease. Antibodies to PC were detected in 51 (24.5%) patients, and antibodies to intrinsic factor were detected in 10 (4.8%). Twenty-five patients with a positive antibody test agreed to participate in the follow-up examination. At the start of observation, none of them had gastrointestinal or hematological symptoms. After 5 years, 6 (24%) of them were histologically diagnosed with AIH (lymphocytic infiltration and/or atrophy of the mucous membrane of the gastric body). When analyzing trends in the concentration of antibodies to PC, it was noted that their levels of autoantibodies gradually increase, reach a peak value and then fall in accordance with the progressive development of GM atrophy and the disappearance of the target autoantigen (proton pump). The authors concluded that the presence of antibodies to PC is a predictor of the development of AIH in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. Therefore, antibody levels measured using a sensitive quantitative immunometric method are relevant for the early diagnosis of AIH [26].

Another study demonstrated that IDA refractory to oral iron therapy in patients with Hashimoto's thyroiditis may be associated with chronic atrophic gastritis [27].

AIH and T1DM

The incidence of AIH increases 3–5 times in patients with T1DM [28]. It is known that T1DM develops mainly as a result of the destruction of pancreatic β-cells by specific autoimmune cells. It is assumed that the autoimmune mechanisms in the development of T1DM and AIH may be similar, so there is a high probability that the same patient may have both diseases. A large meta-analysis of studies published from 1980 to 2014 was conducted, which assessed the association between the presence of autoantibodies to PC and T1DM. The meta-analysis included 3584 patients with T1DM, and the control group included 2650 healthy individuals. The analysis showed that the presence of antibodies to PC was more common among patients with T1DM than among healthy people [29].

Association of AIH with H. pylori

It is well known that H. pylori itself can cause atrophic gastritis. On the other hand, it is important to remember that in many cases, patients with AIH may simultaneously have H. pylori infection [30]. The third possible scenario is the progression of gastritis caused by H. pylori in AIH.

Infection with H. pylori gradually leads to the development of atrophic gastritis [31]. This type of gastritis is most often localized in the antrum of the stomach, but can also spread to the body or be multifocal in nature. Severe atrophy develops over many years, after which H. pylori often disappears from the coolant. In some patients, antibodies to PC appear, resulting in the disease becoming similar to classic AIH [30]. In H. pylori-induced atrophic gastritis, activated CD4+-Th1 cells infiltrating the gastric mucosa cross-recognize the proton pump of these cells and various H. pylori proteins. However, it is unclear whether H. pylori is a factor in Th1 cell activation leading to inflammation and apoptosis [32].

Many patients infected with H. pylori develop a wide range of antibodies - antifoveal, anticanalicular and classical to PC. The most frequently detected are anticanalicular antibodies, which, like anti-PC antibodies, are directed against H+/K+-ATPase [33].

Despite many overlaps, it is important to differentiate AIH from H. pylori-associated gastritis. First of all, it should be remembered that AIH affects the body and fundus of the stomach, while gastritis caused by H. pylori is predominantly localized in the antrum of the stomach.

Other differential diagnostic criteria:

- hyperplasia of enterochromaffin-like cells is more common in AIH;

- PC pseudohypertrophy is more typical for AIH, but it can also be observed in gastritis associated with H. pylori with long-term use of proton pump inhibitors;

- involvement of the fundic glands is more typical for AIH;

- infiltration of lymphocytes and plasma cells of the gastric mucosa involving the deep layers is a sign of AIH, with damage to the superficial layers and active inflammation of atrophic gastritis associated with H. pylori;

- high levels of gastrin-17 are characteristic of AIH and are usually low with H. pylori infection; Prostaglandin levels are low in AIH and may be normal in H. pylori infection [34].

Clinical symptoms of AIH

AIH is asymptomatic for a long time. Its clinical manifestations usually occur after the development of severe glandular atrophy, when gastric cells become unable to produce sufficient quantities of hydrochloric acid, pepsinogens and intrinsic Castle factor. Gastrointestinal symptoms of AIH are not specific. In a study of 99 patients, Miceli et al. [4] showed that most often the diagnosis of AIH was caused by hematological disorders (various forms of anemia; in 37% of cases) and histologically confirmed gastritis – in 34%. In less than 10% of patients, suspicion of AIH is based on the presence of other underlying autoimmune diseases, celiac disease, neurological symptoms, or family history.

IDA is one of the earliest manifestations of AIH; it develops as a result of achlorhydria against the background of atrophy of the fundic glands. Several studies have shown that the cause of refractory or unexplained IDA is often AIH, not only in adults, but also in pediatric populations [35].

PA is a consequence of cobalamin deficiency. Despite the fact that the basic mechanisms of development of megaloblastosis are not fully understood, it is believed that this is largely due to the essential role of cobalamin in DNA synthesis [36]. First, an asymptomatic increase in the average volume of hypersegmented neutrophils is detected. As the disease progresses, patients may complain of weakness, confusion, and palpitations. In later stages, symptoms of angina and congestive heart failure (peripheral edema and shortness of breath) may appear. In addition to the characteristic changes in red blood cells, thrombocytopenia, elevated levels of lactate dehydrogenase and bilirubin (signs of hemolysis) are detected. Cobalamin deficiency leads to hyperhomocysteinemia and endovascular dysfunction, resulting in activation of the coagulation system, increased platelet aggregation, vasoconstriction and an increased risk of thrombosis. Acute myocardial infarction and pulmonary embolism have been described in young patients with severe hyperhomocysteinemia secondary to PsA [37, 38].

Neurological symptoms of cobalamin deficiency are associated with demyelination, subsequent axonal damage and ultimately neuronal death [39]. Interestingly, neurological manifestations due to cobalamin deficiency can be observed in the absence of hematological disorders [40]. Clinically, sensory abnormalities such as loss of vibration sensation and distal paresthesias are detected. Since neurological damage is irreversible, it is extremely important to provide timely parenteral administration of vitamin B12, which can stop the progression of the process [41]. Peripheral neuropathy is another neurological manifestation of PsA. Initial symptoms include paresthesia and numbness of the lower extremities. In this regard, peripheral neuropathy and subacute combined degeneration can be clinically distinguished [42]. Neuropsychiatric conditions associated with PA include mania, depression, obsessive-compulsive disorder, psychosis, and dementia. It should be noted that the use of high doses of vitamins B12, B6 and folic acid slows down and reduces brain atrophy [43].

After the development of hypo- and achlorhydria, AIH usually manifests itself only with vague dyspeptic symptoms, such as bloating, early satiety and epigastric discomfort [44]. One of the consequences of cobalamin deficiency is atrophic glossitis, manifested by a burning sensation of the tongue [45]. In Italy, from 1995 to 2013, a survey of 379 patients with AIH was carried out, in whom gastrointestinal symptoms were assessed in accordance with the Rome III criteria, the relationship between them and signs of anemia, the presence of autoantibodies to PC and intrinsic factor, H. pylori infection and associated autoimmune diseases. Women predominated (70.2%), the average age of patients was 55 years (range: 17–83). PA was detected in 53.6% of patients, IDA – in 34.8%, antibodies to PC – in 68.8%, combination with other autoimmune diseases – in 41.7%. Thyroid diseases dominated (89%), among others - vitiligo, alopecia, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, hemolytic anemia, Sjögren's syndrome, psoriasis, autoimmune hepatitis and myasthenia gravis.

H. pylori infection was diagnosed in 26.1% of cases. None of the patients had stomach cancer. Gastrointestinal symptoms were noted in 56.7% of patients, 69.8% of them had complaints exclusively in relation to the upper parts of the digestive tract, 15.8% – in its lower parts, and 14.4% – a combination of both. The most pronounced was postprandial dyspepsia, present in 60.2% of patients [46].

Diagnosis of AIH

Determination of antibodies to gastric PC is considered the optimal screening test for AIH, and determination of antibodies to intrinsic factor is a reserve method for confirming the diagnosis. Vitamin B12 levels do not correlate with antibody titers. Levels of antibodies to PC and hypergastrinemia significantly correlate with inflammation of the fundic glands of the gastric mucosa, and levels of autoantibodies to intrinsic factor correlate with its atrophy [47].

PC loss results in major functional changes. Hypergastrinemia, detected in almost all patients, is the result of stimulation of gastrin-producing G cells under conditions of achlorhydria. The loss of the chief cells of the fundic glands leads to a gradual decrease in the serum level of pepsinogen I, while the level of pepsinogen II (maintained by the normal secretion of unaffected antral glands) does not change significantly. This results in a decreasing pepsinogen I/II ratio. Thus, the typical serological profile of AIH is hypergastrinemia and a gradual decrease in the pepsinogen I/II ratio [34].

A biopsy followed by histological examination is considered the most reliable method for diagnosing metaplastic atrophic gastritis. However, under conditions of severe inflammation, it is difficult to reliably assess the atrophy of the fundic glands. Another reason for misinterpretation of histological results may be the early stages of AIH. The morphological picture of AIH is characterized by: 1) infiltrates of lymphocytes and plasma cells in the lamina propria, 2) focal atrophy of the fundic glands of the coolant along with the subepithelial capillary network, 3) pseudohypertrophy of the PC and 4) hyperplasia of enterochromaffin-like cells. Because hyperplasia is a precursor to gastric neuroendocrine tumors, it is important to stain samples with CgA and synaptophysin [48].

Long-term studies indicate that in early AIH there are no significant changes in the antrum of the stomach in the absence of H. pylori infection: the epithelium is either normal or foveal hyperplasia (“reactive gastropathy”) is detected, probably associated with the trophic effect of hypergastrinemia [49 ]. As AIH progresses, an uneven loss of fundic glands occurs, which leads to the appearance of pseudopolyposis. Such a macroscopic picture suggests the need to take a biopsy during endoscopic examination both from the polypoid-like changed coolant and from its apparently unchanged areas. Coolant atrophy can occur in two different forms. In one of them, the disappearing glandular cells are replaced by fibrous tissue, which is not accompanied by a change in the glandular phenotype. In the second form, the glands of the coolant are replaced by metaplastic glands [50]. The progressive replacement of functionally specialized gastric glands with non-functioning fibrous tissue or metaplastic cells leads to the loss of the main functions of the fundic glands of the coolant, one of which is the production of hydrochloric acid.

Neuroendocrine tumors of the stomach (endocrine carcinomas)

Receptors for gastrin are present on the membranes of not only PCs, but also enterochromaffin-like cells. With the long-term existence of AIH, atrophic changes in the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach progress, where PCs are concentrated. A decrease in the amount of PC leads to a decrease in the secretion of hydrochloric acid. Hypo- and achlorhydria lead to hypergastrinemia, gastrin stimulates receptors on enterochromaffin-like cells, leading to hyperplasia followed by dysplasia, considered a precancerous lesion that can progress to endocrine carcinoma type 1 [51]. There are 3 types of gastric endocrine carcinomas: type I is associated with AIH, type II may be present in patients with multiple endocrine neoplasia type I and Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, and type III, the most aggressive variant, usually occurs sporadically. Serum gastrin levels vary depending on the type of carcinoma: types I and II are characterized by high levels, while type III are normal [52]. Polypoid formations of the gastric body in patients with AIH are often neuroendocrine tumors. These lesions are usually asymptomatic, although dyspepsia and IDA may occur. The diagnosis is usually made by endoscopic and morphological studies [53].

Treatment of AIH

Pathogenetic therapy for AIH has not been developed. Symptomatic treatment of AIH depends on clinical manifestations and laboratory results. In the early stages of the disease, before progression of PA, it is recommended to take iron, folic acid and cobalamin. Oral administration of vitamin B12 is possible, as it has been shown that 1% free vitamin B12 can be absorbed in the small intestine by passive diffusion. However, parenteral administration of vitamin B12 is recommended for patients with neurological manifestations. Since AIH is often combined with other autoimmune diseases, appropriate diagnostic workup and treatment are necessary [54].

It has also been shown that eradication therapy of patients with the presence of H. pylori leads to a decrease in the activity and severity of gastritis and in 80% of cases inhibits the progression of coolant atrophy when observed for 2 years. Thus, eradication of H. pylori in patients with AIH is a mandatory condition for the treatment of this disease [55].