Pathological changes in the gastrointestinal tract in children are among the most common problems in pediatrics. According to the latest statistics, damage to the upper digestive tract (gastritis, gastroduodenitis, gastroesophageal reflux disease) is diagnosed in almost 30% of children. The leading position in the structure of gastroenterological diseases in the age category of patients under 18 years is occupied by gastroduodenitis (more than 60% of cases). This pathology is more common in school-age children and teenagers (which is associated with eating disorders, emotional lability, and somatoform dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system). But the current trend towards reducing the age of patients with inflammation of the stomach and duodenum is helping to intensify the search for an effective solution to this problem.

Chronic gastroduodenitis is a nonspecific inflammatory disease of the stomach and duodenum, which manifests itself as a violation of the secretory and motor functions of the entire gastrointestinal tract. Pathological changes in the mucous membrane are represented by cell degeneration with pronounced inflammatory signs.

Age-related features of the development of gastrointestinal diseases

Gastroduodenitis in children manifests itself with the same symptoms as in adults

Starting from preschool age, children begin to suffer from stomach and intestinal diseases. Even with adequate measures to eliminate the disease, the disease is not completely cured and, if unfavorable conditions are created, it relapses.

This worsens the anatomical and histological structure of vital internal organs. The course of the disease can end tragically: disability, loss of the ability to lead a full life.

The situation is complicated by the fact that in children the clinical picture of the disease is often non-standard: it can be erased, the nature of its course may have atypical symptoms, and the signs may be mild. Also alarming is the appearance of destructive changes in childhood, manifested in ulcerative defects.

Symptoms of duodenitis in a child

The signs of this disease are very diverse and are similar to peptic ulcers. Common symptoms are:

- severe stabbing and cutting paroxysmal pain before eating or 2-3 hours after it, localized in the stomach or right hypochondrium;

- nausea;

- sour belching;

- heartburn;

- vomit;

- sometimes constipation;

- insomnia;

- headache;

- decreased appetite;

- prostration;

- tearfulness, irritability;

- pale skin. Source: A.A. Baranov, P.L. Shcherbakov Current issues in pediatric gastroenterology // Issues of modern pediatrics. 2002. T. 1, No. 1. P. 12-16

In approximately 50% of children, the disease worsens during the off-season.

In the chronic form, a good appetite usually remains. Symptoms include heartburn, sour belching, increased thirst, abdominal pain, white coating on the tongue, and frequent constipation.

The advanced disease is characterized by weakness, rapid fatigue, belching of air, nausea and a feeling of a full stomach after eating, dull weak pain, gas formation, and diarrhea.

Reasons for the development of gastroduodenitis in childhood

Among the reasons that influence the development of gastroduodenitis, there are two main groups:

- endogenous,

- exogenous.

Endogenous reasons include the following:

- genetic predisposition;

- excessive acidity;

- disruptions in mucus production;

- circulatory disorders in the area of the digestive organs;

- diseases leading to hypoxia of the digestive organs;

- poisoning;

- cases of body intoxication;

- diseases of the hepato-biliary system

The following are considered exogenous causes:

Causes of the disease

The chronic form is provoked by:

- food allergies;

- infection with parasites (helminths, Giardia);

- certain medications;

- severe constant stress.

In its acute form, the disease manifests itself due to:

- peptic ulcer;

- diseases of the biliary tract;

- chronic gastritis;

- diverticulosis;

- chronic pancreatitis;

- high content of hydrochloric acid and pepsin in gastric juice;

- duodenostasis;

- insufficient secretin production;

- genetic predisposition;

- disturbances of local blood flow;

- intoxication of the body;

- hypoxia of organs and tissues;

- poor quality food, improper diet and/or diet;

- food poisoning;

- acute intestinal infections;

- reduced local immunity.

Types of disease

The disease is classified in several ways. Firstly, for the reasons for the occurrence of the disease:

- infectious lesions (viral, Helicobacter, fungal varieties);

- autoimmune aggressive effects;

- allergies;

- granulomatous and eosinophilic forms (they stand apart).

Prevention of gastroduodenitis - proper nutrition

There are diseases for which the cause cannot be determined. Secondly, the localization of inflammatory manifestations can be taken as the basis for classification. In this case, you can rely on the following changes:

- antrum of the fundus;

- widespread inflammation (pangastritis).

Thirdly, morphological changes can also become the basis for identifying varieties of the disease, for example:

- surface;

- hypertrophic;

- erosive;

- hemorrhagic;

- subatrophic;

- mixed

These changes are detected during endoscopic examination. Gastric secretion can also influence the formulation of the attribution of a disease to a particular variety. In particular, it can be increased, decreased, normal. There are three stages of the disease:

Diagnosis of gastroduodenitis

An experienced doctor, even during the first examination of a child with chronic gastroduodenitis, immediately draws attention to the patient’s appearance: he is pale, there are bruises under the eyes, the skin is dry and inelastic.

During a physical examination, the pediatrician identifies pathognomonic symptoms of this disease:

- the tongue is dry, covered with a white coating;

- positive Mendelian symptom – pain in the epigastrium upon percussion of the abdomen;

- signs of hypovitaminosis: hair loss, brittle nails, etc.

Laboratory and instrumental examination of the child includes:

- general blood analysis;

- general urine analysis;

- fecal analysis for helminth eggs;

- coprogram;

- biochemical blood test to determine the level of total protein and its fractions;

- stool analysis for occult blood (Gregersen reaction) - to exclude the erosive form of pathology and peptic ulcer disease;

- rapid or breath urease test for Helicobacter pylori;

- stool analysis for the concentration of antigens to Helicobacter pylori using ELISA;

- fibrogastroduodenoscopy is the “gold standard” for diagnosing gastroduodenitis. This method allows you to determine macroscopic (during manipulation) and microscopic (during morphological study of a tissue sample) changes in the mucous membrane of the affected area. The greatest advantage of endoscopy is the ability to perform a biopsy during the examination;

- pH-metry is performed to assess acid formation in the stomach. Based on the results of this study, a hypoacid, normacid or hyperacid state is determined;

- An ultrasound of the abdominal cavity and retroperitoneal space is performed to exclude other causes of dyspeptic disorder.

Types of clinical manifestations of gastroduodenitis

Inpatient treatment of gastroduodent

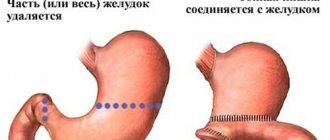

If chronic gastroduodenitis is caused by exogenous factors, changes occur in the mucosa in the antrum of the stomach, as well as in the duodenum. At the same time, signs of inflammation and erosion are revealed. Subatrophic or hypertrophic signs may appear.

Sometimes there is a combination of them. In this case, we can talk about gastroduodenitis, simply duodenitis, antral gastritis, erosive duodenitis.

In this case, problems arise with the motor and secretory functions of the stomach. A sick child is characterized by irritability, nervousness, and symptoms of cephalalgia can be observed. Appetite remains. Frequent cardiac failure leads to dyspeptic disorders, which manifest themselves in sour belching and heartburn.

The main feature of this form is increased acidity, preservation or increase in the formation of enzymes.

Some children complain of thirst. Pain is present in almost all patients. They are localized in the epigastric region or in the pyloroduodenal region. Moreover, they make themselves felt both on an empty stomach and after eating. Such children usually suffer from constipation. Upon examination, you can see a coated tongue.

With a long course of the disease, inflammation affects the fundus. This is the second form of the disease. In addition to inflammatory, atrophic, subatrophic changes, erosive lesions localized in the middle third of the stomach are added. With these changes, we can talk about the nosological form of gastroduodenitis, manifested in gastritis of the fundus of the stomach, gastroduodenitis that has captured the glandular apparatus of the stomach, and in erosive lesions of the mucous membrane.

Ambiguous answers to simple questions about chronic gastroduodenitis in children

In recent years, when there has been an increase in the prevalence of gastroenterological pathology among children of all age groups [1], the share of chronic gastroduodenitis in its structure accounts for almost 45% among children of primary school age, 73% among children of middle school age and 65% among high school students. Moreover, the decrease in relative frequency with age occurs due to an increase in the proportion of peptic ulcer disease [2]! In this regard, consideration of this pathology from the perspective of unsolved problems seems very relevant.

Question one: chronic gastroduodenitis or chronic gastritis and chronic duodenitis? The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-X, section K29) suggests diagnosing “chronic gastritis” (chronic superficial gastritis - K29.3, chronic atrophic gastritis - K29.4, unspecified chronic gastritis - K29.5) and “duodenitis” (K29. ), nevertheless leaving the possibility of combinations in the form of item K29.9 - gastroduodenitis, unspecified. At the same time, it is obvious that the meaning that was originally intended for this paragraph by the authors of the classification differs from what domestic pediatricians assume, especially since it does not contain the clarification “chronic”. On the one hand, gastritis and duodenitis are indeed different diseases with different, at first glance, pathogenetic mechanisms. On the other hand, these differences seem significant only at first glance. Both diseases have a lot in common, which leads to their combination in almost all patients and the relative rarity of isolated forms in childhood. Both diseases can be classified as so-called. acid-dependent conditions that develop when there is an imbalance of protective and aggressive factors in the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum. One of these aggression factors is Helicobacter pylorus, but its role has been proven in the case of chronic gastritis and is less obvious in chronic duodenitis. In the development of the latter, the acid-peptic factor apparently plays a more significant role. Most likely, there is a single pathogenetic process leading to the development of gastritis in the stomach and duodenitis in the duodenum. Moreover, the process in the stomach determines and supports the process in the duodenum and vice versa, and in this light gastroduodenitis should be considered as a whole. The domestic pediatric school has traditionally adhered to the combination of these nosological units into a single diagnosis, and there is no reason to revise this position.

Question two: what is the role of Helicobacter pyloricus in the development of chronic gastroduodenitis? The pathogenetic role of Helicobacter pyloricus has been proven for chronic gastritis. However, the question remains whether Helicobacter pylori plays a decisive role in all cases of chronic gastritis in children. There are several reasons for this question. Firstly, infection with Helicobacter pylorus in general in our country is quite high (60–70% [3]), and the frequency of chronic gastroduodenitis and, especially, peptic ulcer disease is much lower. That is, the fact of infection with Helicobacter pyloricus is not decisive for the development of these diseases. This discrepancy may be associated both with the existence of different strains of Helicobacter pyloricus, which have a different set of pathogenicity factors, and with the characteristics of a particular macroorganism, allowing infection and damage to the mucous membrane. Secondly, the infection rate of children is inversely proportional to their age. It is less common in preschool children, but the diagnosis of “gastroduodenitis” and even “peptic ulcer” also occurs in this age group. This pattern was established already in the first works on studying the role of Helicobacter pylori infection in children, and domestic researchers were pioneers in this direction [4, 5, 6].

Noteworthy is the significant increase in the incidence of chronic gastroduodenitis after the start of school. This circumstance can be explained by an increase in the child’s social circle and, consequently, an increase in the risk of infection with Helicobacter pyloric. However, the significance of the psychogenic factor seems no less probable, since the beginning of schooling radically changes the child’s entire lifestyle and is characterized by an increase in physical and emotional stress and a change in the nature of nutrition. Significant stress, provoking autonomic disorders and, as a consequence, disturbances in gastrointestinal motility and gastric secretion, leads to the formation of first functional disorders of the digestive system, and then organic ones. Indeed, the proportion of functional disorders that predominate in preschool children progressively decreases with age: approximately 50% in children of primary school age, 19% in middle school children, and 16% in older children [2]. The importance of the psychoemotional factor and autonomic disorders in the development of gastroduodenal pathology was pointed out in the works of gastroenterologists of the “pre-Helicobacter” era; this idea is confirmed by the results of modern research [7]. Finally, hereditary predisposition also plays an unconditional role.

And yet, foreign research in the field of gastritis in general and in children in particular concentrates mainly on Helicobacter pylorus. To date, the mechanisms of its interaction with the macroorganism have been studied in sufficient detail, and diagnostic and eradication algorithms have been developed. At the same time, “non-Helicobacter” ways of development of gastritis and duodenitis (which, by the way, are not denied) are practically not touched upon in these studies [8, 9, 10–14]. For example, in an extensive study by Bulgarian specialists, the results of testing children for Helicobacter pylorus, as well as for Helicobacter heilmannii, were analyzed for the period from 1996 to 2006. Pyloric Helicobacter was detected in 77.8% of children with peptic ulcer disease and in 64.5% of children with chronic gastritis. H. heilmannii was identified in two cases [15]. In another study of 210 endoscopies, Helicobacter pylori was detected in 45.9% of children. Moreover, the average age of children with detected Helicobacter was significantly higher than the age of children without Helicobacter (11 years and 8.9 years, respectively, p = 0.009). According to the results of this work, nodular gastritis was definitely associated with the presence of Helicobacter pyloricus, and esophagitis - with its absence. The presence of chronic gastritis was confirmed histologically in all Helicobacter-positive patients [16].

Thus, Helicobacter pyloricus obviously plays a role in the development of chronic gastroduodenitis, but psychogenic factors, the state of the autonomic nervous system, and nutritional factors are also important.

Question three: how to legitimately make this diagnosis? In everyday practice, the diagnosis of chronic gastroduodenitis is made after an endoscopic examination, which has practically become routine for patients with complaints of abdominal pain, although there is currently a tendency to revise this approach, primarily for financial reasons. At the same time, the correlation between the endoscopic conclusion and the morphological picture is relatively weak. At the same time, morphological diagnosis in every case suspected of chronic gastroduodenitis is unrealistic and unjustified either financially or ethically. Does this mean that we do not have the right to make this diagnosis in most clinical cases? If yes, then you should follow the path trodden by Western doctors and proposed by a number of domestic pediatricians [17] - make a diagnosis of “dyspepsia syndrome” at the appropriate clinic, taking as a working hypothesis that the child has functional dyspepsia, and carry out appropriate treatment. If the treatment is successful, then the diagnosis of “functional dyspepsia” is considered confirmed, and if not, an in-depth examination is carried out, including endoscopy and morphological examination.

Another approach is to turn a blind eye to the discrepancy between endoscopic and morphological signs of the inflammatory process and make a diagnosis of “chronic gastroduodenitis”, as before, based only on endoscopic data, deliberately going for overdiagnosis.

Of course, the first way is more honest and correct, but the problem is that in many institutions morphological examination cannot yet be implemented, while endoscopy is carried out almost everywhere. In this situation, the second approach could be considered justified, since it immediately provides for more intensive treatment.

However, the question of morphological research has another side. It is this that makes it possible to make a differentiated diagnosis, reliably identifying, in particular, atrophic gastritis, which is not uncommon in pediatric practice. Thus, according to S. Boukthir et al. atrophic gastritis is detected in 14.5% of children, and in almost all of them Helicobacter pyloric was detected and in many - the so-called. “nodular” gastritis [18]. Widespread use of morphological data would allow a more effective approach to the treatment of these patients.

Question four: what are the consequences of chronic gastroduodenitis? For a long time it was believed that chronic gastroduodenitis was a pre-ulcerative condition, but many credible studies have shown that this is not the case. Chronic gastroduodenitis and peptic ulcer disease, although they have much in common, are still distinct diseases that differ, apparently, at the level of hereditary predisposition. This is the only way to explain that under similar environmental conditions, gastritis and duodenitis develop in some cases, and ulcers in others. Thus, to date there is no convincing data on any evolution of chronic gastroduodenitis in children. There are also no works tracing its evolution as the child transitions into adulthood. On the other hand, atrophic gastritis determines the risk, albeit in the distant future, of developing gastric cancer, which once again emphasizes the importance of expanded diagnostics, and also raises the question of the need for new research in this direction.

Question five: how to treat chronic gastroduodenitis? Treatment of chronic gastroduodenitis in children, as a rule, includes the use of antacid, antisecretory and anti-Helicobacter drugs. The effectiveness of this approach has been proven in many domestic studies, but the practical doctor gets the impression that it is somewhat redundant. Taking into account the step-by-step diagnostic approach described above, treatment begins with behavior correction, elimination of traumatic factors, vegetative status, motor disorders, etc., i.e., with the treatment of functional dyspepsia. The actual treatment of chronic gastroduodenitis, in addition to all of the above, includes antacid drugs, possibly antisecretory drugs and, if Helicobacter pyloric is detected, anti-Helicobacter drugs. That is, when diagnosing “chronic gastroduodenitis,” it is advisable to conduct a study of gastric secretion and some kind of test for Helicobacter pyloricus.

Question six: is it necessary to follow a diet for chronic gastroduodenitis? For many decades, patients with chronic gastroduodenitis have been recommended to follow a diet similar to that for peptic ulcers. For chronic gastroduodenitis with high acidity, it is recommended to prescribe tables N1a, N1b (Institute of Nutrition of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences), for chronic gastroduodenitis with secretory insufficiency - a diet that includes juice substances (table N2). It is recommended to adhere to these diets even after the child is discharged from the hospital for 3–12 months. In the future, the diet expands, but smoked meats, canned food, lamb and pork are excluded [19].

Unfortunately, there are no studies of the effectiveness of this approach from the standpoint of evidence-based medicine, which raises the question of how justified it is. Naturally, without carrying out appropriate work it is impossible to answer this question unambiguously, however, practical experience suggests that children with chronic gastroduodenitis can receive age-appropriate balanced nutrition without products that are excessively irritating to the mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract. This is all the more justified because even with peptic ulcer disease, there is currently a departure from the traditional dietary recommendations for our country. However, spices, spices, pickles, smoked meats, fatty foods (fatty meat and fish), as well as dairy products should definitely be excluded from the diet due to the high incidence of lactase deficiency and allergies to cow's milk proteins in such patients.

The questions and answers presented above are, of course, debatable, but it is obvious that chronic gastroduodenitis, despite its apparent “banality,” poses serious questions to the doctor and researcher that require resolution.

Literature

- Volkov A.I. Chronic gastroduodenitis and peptic ulcer in children // Russian Medical Journal. 1999. T. 7. No. 4 (88). pp. 179–86.

- Krasnova E. E. Diseases of the stomach and duodenum in children. Dis... doc. honey. Sci. Ivanovo, 2005.

- Shcherbakov P. L. Epidemiology of helicobacteriosis. Gastroenterology of childhood. Ed. S. V. Belmer and A. I. Khavkin. M., 2003.

- Mazurin A.V., Shcherbakov P.L., Gershman G.B., Filin V.A., Boxer V.O., Grigoriev P.Ya., Smotrova I.A. Pyloric campylobacteriosis in children (endoscopic and histological studies ) // Question ocher mat. and children 1989. No. 3. pp. 12–15.

- Korovina N. A., Levitskaya S. V., Boxer G. V., Spirina T. S., Girshovich E. S. Clinical and epidemiological features of gastroduodenal campylobacteriosis in children // Pediatrics. 1989. No. 8. P. 9–13.

- Mazurin A.V., Filin V.A., Tsvetkova L.N., Shcherbakov P.L., Salmova V.S., Trifonova I.V. Features of Helicobacter-associated pathology of the upper digestive tract in children and modern approaches to its treatment // Pediatrics. 1996. No. 2. P. 42–45.

- Kotovsky A.V. Prognostic criteria for the development of peptic ulcer disease and chronic gastroduodenitis in children and adolescents (medical and social aspect) // Russian Biomedical Journal. 2007. T. 8. pp. 292–297.

- Naous A., Al-Tannir M., Naja Z., Ziade F., El-Rajab M. Fecoprevalence and determinants of Helicobacter pylori infection among asymptomatic children in Lebanon // J Med Lebanon. 2007. Vol. 55(3). P. 138–144.

- Qualia CM, Katzman PJ, Brown MR, Kooros K. A report of two children with Helicobacter heilmannii gastritis and review of the literature // Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2007. Vol. 10 (5). P. 391–394.

- Poddar U., Yachha SK Helicobacter pylori in children: an Indian perspective // Indian Pediatr. 2007. Vol. 44 (10). P. 761–770.

- Harris PR, Wright SW, Serrano C., Riera F., Duarte I., Torres J., Pena A., Rollan A., Viviani P., Guiraldes E., Schmitz JM, Lorenz RG, Novak L., Smythies LE , Smith PD Helicobacter pylori gastritis in children is associated with a regulatory T-cell response // Gastroenterology. 2008. Vol. 134(2). P. 491–499.

- Sabbi T., De Angelis P., Dall'Oglio L. Helicobacter pylori infection in children: management and pharmacotherapy // Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2008. Vol. 9 (4). P. 577–85.

- Soylu OB, Ozturk Y., Ozer E. Alpha-defensin expression in the gastric tissue of children with Helicobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis: an immunohistochemical study // J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2008. Vol. 46(4). P. 474–477.

- Dzierzanowska-Fangrat K., Michalkiewicz J., Cielecka-Kuszyk J., Nowak M., Celinska-Cedro D., Rozynek E., Dzierzanowska D., Crabtree JE Enhanced gastric IL-18 mRNA expression in Helicobacter pylori-infected children is associated with macrophage infiltration, IL-8, and IL-1 beta mRNA expression // Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008. Vol. 20 (4). P. 314–319.

- Boyanova L., Lazarova E., Jelev C., Gergova G., Mitov I. Helicobacter pylori and Helicobacter heilmannii in untreated Bulgarian children over a period of 10 years // J Med Microbiol. 2007. Vol. 56 (Pt 8). P. 1081–1085.

- Urribarri AM, Garcia JC, Rivera AB, Cardo DC, Saito AM, Angeles FT Helicobacter pylori in children seen in Cayetano Heredia National Hospital (HNCH) between 2003 and 2006 // Rev Gastroenterol Peru. 2008. Vol. 28(2). P. 109–118.

- Pechkurov D.V., Shcherbakov P.L., Kanganova T.I. Dyspepsia syndrome in children: modern approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Information and methodological materials for pediatricians, gastroenterologists and family doctors. Samara, 2005. 20 p.

- Boukthir S., Aouididi F., Mazigh Mrad S., Fetni I., Bouyahya O., Gharsallah L., Sammoud A. Chronic gastritis in children // Tunis Med. 2007. Vol. 85(9). P. 756–760.

- Volkov A.I. Chronic gastroduodenitis and peptic ulcer in children // Russian Medical Journal. 1999. T. 7. No. 4 (88). pp. 179–186.

S. V. Belmer, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor T. V. Gasilina, Candidate of Medical Sciences

RNIMU named after. N. I. Pirogova, Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Drug treatment

The list of medications includes:

- antibiotics for diagnosed H. pylori infection;

- antisecretory drugs for the form with high acidity;

- antacids to relieve heartburn;

- if indicated - antispasmodic and enzyme preparations, vitamins, reparation stimulants, sedatives and herbal remedies.

Complex treatment of the disease continues for several weeks. If symptoms are severe, it is recommended to begin therapy in a hospital followed by continuation on an outpatient basis.

Classification

There is no generally accepted classification. Forms and types are divided according to the course and visual picture of inflammation obtained during gastroduodenoscopy. Depending on the mechanism of formation, gastroduodenitis can be: primary, secondary (against the background of other lesions of the digestive tract).

According to the clinical course, it is customary to distinguish: acute gastroduodenitis - occurs rarely with food poisoning, lasts up to three months, in 30% of children it is asymptomatic and goes into the chronic stage, chronic - is accompanied by the previously described signs of morphological restructuring of the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum, each exacerbation aggravates the disorders .

In the chronic course there are:

- phases - exacerbation, complete and incomplete remission;

- depending on the changes detected during endoscopy - superficial, hyperplastic, atrophic and erosive;

- according to histological characteristics - the degree of inflammation (mild, moderate, severe), atrophic changes in cells, gastric metaplasia of the epithelium are revealed.

Prevention methods

To protect a child from gastroduodenitis, it is important to control and monitor the diet according to the regimen and quality. Avoid feeding your baby “adult” food. The child should be protected from overload, time for rest should be observed, and walks should be arranged.

If a pediatrician refers children to a gastroenterologist, you need to get as much information as possible and follow them in organizing treatment. How healthy a generation of children will grow up depends on the attention of adults. Untreated gastroduodenitis leads already at a young age to the appearance of peptic ulcers with subsequent complications.