General information

Hepatitis A is a liver disease caused by the hepatitis A virus. The hepatitis A virus is distinguished by record resistance to external influences: boiling - inactivation of the virus occurs only after 5 minutes. Chlorine – 30 min. Formalin – 72 hours. 20% ethyl alcohol is not inactivated. Acidic environment (pH 3.0) – does not inactivate, survival in water (temperature 20°C) – 3 days.

The hepatitis A virus is spread primarily when an uninfected (or unvaccinated) person consumes food or water contaminated with feces from an infected person. The virus can also be transmitted through close physical contact with an infected person, but hepatitis is not transmitted through casual contact between people. The disease is closely linked to a lack of safe water, inadequate sanitation and poor personal hygiene. The sources of the virus are sick people.

The disease can cause significant economic and social impacts in individual communities. It can take weeks or months for people to get healthy enough to return to work, school and everyday life.

Hepatitis B: features and distinctive aspects

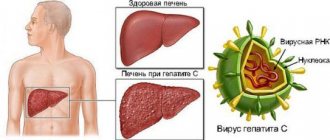

Hepatitis B can be acute, but a small number of people develop the chronic form. Infection with viral hepatitis B occurs through the entry of the virus through damaged skin and mucous membranes, and the infection is transmitted through biological fluids.

The following can cause infection:

- blood transfusion;

- use of contaminated instruments (tattoos, piercings, manicures);

- injection drug use;

- transmission of the virus from mother to child;

- sharing personal hygiene products;

- unprotected sexual intercourse.

The period between infection and the onset of symptoms for viral hepatitis B is from 30 to 180 days.

Hepatitis B is asymptomatic in most cases. Some patients have a clinical picture similar to hepatitis A:

- headache;

- emotional imbalance;

- severe weakness,

- fast fatiguability;

- loss of appetite, nausea;

- bitterness, feeling of heaviness and pain in the right hypochondrium;

- pain in joints and muscles;

- febrile temperature,

- skin itching, pigmentation.

Chance of getting sick

Anyone who has not been vaccinated or previously infected can become infected with hepatitis A. In areas where the virus is widespread (high endemicity), most hepatitis A infections occur among young children. Risk factors include the following:

- poor sanitation;

- lack of safe water;

- injection drug use;

- living together with an infected person;

- sexual relations with a person with acute hepatitis A infection;

- travel to areas with high hepatitis A endemicity without prior immunization.

In developing countries with very poor sanitation and hygiene practices, most children (90%) acquire hepatitis A viral infection before they reach 10 years of age.

In cities where it is easier to comply with hygienic requirements, a person remains susceptible longer, which, paradoxically, leads to a higher incidence of icteric and sometimes severe forms of hepatitis A in city residents. Thus, city residents traveling to the countryside are also a risk group.

Causes

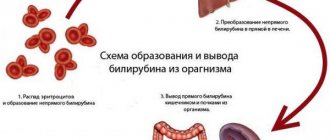

Most often, jaundice is caused by hepatitis of viral etiology, types A, B, C, D, E. This is an infectious disease that selectively affects the liver, causing acute or chronic inflammation in its tissue (parenchyma). Yellowing of the skin with it has a separate name - parenchymal, or hepatic jaundice. The pathogen is transmitted using the following routes:

1. Fecal-oral.

Virus types A and E are the cause of acute hepatitis. For infection to occur, it only needs to enter the oral cavity - with unboiled water or food. Even towels, dishes and toothbrushes are unsafe - this method is called contact-household and is less common.

Jaundice is transmitted as an epidemic outbreak in large groups, preferably children, since the desire to taste surrounding objects or touch food without washing your hands is an ideal “entry gate” for the virus.

2. Parenteral.

Is jaundice transmitted through household or airborne transmission? Jaundice caused by viruses types B, C, D is quite contagious, but cases of transmission through intact skin, household objects or airborne droplets have not been recorded. The virus is found in high concentrations in the blood; a smaller amount is in sperm and vaginal secretions.

The number of viral particles in sweat and saliva is negligible, which does not eliminate the danger of infection through a kiss - but only if both partners have wounds on the oral mucosa.

The causes of jaundice in parenteral hepatitis are varied.

It is transmitted through contact with blood - blood transfusions (transfusion of blood and components), invasive dental, surgical, cosmetic procedures (violating the integrity of the skin and mucous membranes). A special risk group is people who use injection drugs.

Sexual intercourse not protected by a condom also carries the risk of contracting jaundice. How can a child become infected if the mother is diagnosed with jaundice? Infection occurs vertically, i.e. in utero from the pregnant woman to the fetus, lactation - during breastfeeding.

In the acute form of the disease, it is impossible to determine the type of hepatitis without specific diagnostics. In most cases, the period of primary infection does not manifest itself, and the disease, taking advantage of weaknesses in the immune system, becomes chronic.

How is jaundice most often transmitted from person to person? Previously, it was believed that the most common cause of jaundice was Botkin's disease, or hepatitis A. But with the improvement of laboratory methods and the introduction of mandatory screening in risk groups among the population, the incidence of parenteral hepatitis has increased sharply.

This is explained by the large number of infected donors, the need of patients for blood transfusions, as well as the long latent (hidden) period of hepatitis, when the health status does not cause concern.

The use of tests that can detect the virus helps clarify the accuracy of the doctor's suspected diagnosis, but at the same time contributes to the impressive statistics.

Symptoms

The incubation period for hepatitis A usually lasts from two to six weeks, with an average of 28 days. Symptoms of the disease can be mild or severe. These may include fever, malaise, loss of appetite, diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal discomfort, dark urine, and jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes). Not all infected people show all of these symptoms.

Signs and symptoms of hepatitis A are more common in adults than in children, and the risk of severe disease and death is higher in older adults. Infected children under six years of age usually do not show any noticeable symptoms, and only 10% develop jaundice. Among older children and adults, hepatitis A occurs with more severe symptoms, and jaundice develops in more than 70% of cases.

Unlike hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A does not cause the development of a chronic form of the disease.

Complications after an illness

Recurrent hepatitis A, observed 4-15 weeks after the onset of symptoms, cholestatic hepatitis A, characterized by jaundice and itching, fulminant hepatitis A (characterized by high fever, severe abdominal pain, vomiting, jaundice in combination with seizures).

The most severe clinical forms of viral hepatitis A are cholestatic (cholestasis - literally “stagnation of bile”) and fulminant (fulminant). With the first, the dominant symptoms are severe jaundice, significant enlargement of the liver and severe skin itching, which is caused by irritation of the nerve receptors of the skin by bile components. Stagnation of bile in this form of viral hepatitis A is caused by significant inflammation of the walls of the bile ducts and the liver as a whole. Despite the more severe course, the prognosis for the cholestatic form of hepatitis A remains favorable. This cannot be said about the fulminant, fulminant form of the disease, which, fortunately, is quite rare among children and young adults (frequency is a fraction of a percent), but not uncommon in elderly patients (several percent of cases). Death occurs within a few days due to acute liver failure.

Treatment of viral hepatitis A

Hepatitis A treatment is usually done at home. Only patients with severe forms of the disease are hospitalized. In the first days until you feel better, bed rest is recommended, then it gradually expands.

Diet for hepatitis A includes:

- proteins: dairy products, lean meat and fish, omelet;

- fats: butter, olive, sunflower oil;

- carbohydrates: rice, oatmeal, buckwheat porridge, potatoes, pasta, sugar, vegetables, juices, fruits;

- salads, vinaigrette, honey, marshmallows, jam, prunes, dried apricots, raisins, bread are allowed.

Prohibited:

- pork, other fatty meats, poultry or fish;

- canned food;

- sausage;

- legumes;

- confectionery and chocolate;

- marinades and spices;

- garlic, radishes, hot cheese, mayonnaise and other foods that irritate the digestive tract.

Choleretic agents, vitamins, essential phospholipids, ursosan, and enterosorbents are prescribed.

Antiviral drugs and antibiotics are not used. Traditional methods of treatment:

- infusion of valerian, hawthorn and mint;

- infusion of immortelle, yarrow, wormwood and dill;

- infusion of rosehip and rowan berries;

- raw potato juice.

Vaccines

There are several hepatitis A vaccines available on the international market. They are all similar in terms of how well they protect people from the virus and the side effects. There are no licensed vaccines for children under one year of age. All inactivated vaccines are formalin- and heat-inactivated hepatitis A viruses and are the most widely used in the world, and live attenuated vaccines, which are produced in China and used in several other countries.

Many countries use a two-dose schedule using inactivated hepatitis A vaccine, but other countries may include a single dose of inactivated hepatitis A vaccine in their immunization schedules.

More about vaccines

Prevention of hepatitis A

There is nonspecific and specific prevention of hepatitis A. Anti-epidemic measures:

- when a case of illness is detected, all contact persons are examined and their blood is taken for analysis for early detection of the epidemic;

- current and final disinfection is carried out at the source of the disease, and the quality of water and food is carefully monitored;

- Those in contact with the patient are given ready-made antibodies in the form of immunoglobulin.

Immunoglobulin is not a vaccination against hepatitis A, but only a measure to support the body’s defense against the virus. It is administered in the first 7 days after diagnosis of the disease in the outbreak.

The only way to reliably protect a child from the virus is the hepatitis A vaccine. Domestic drugs are approved for use, as well as the vaccines Havrix, Avaxim, Vakta, Twinrix. They are well tolerated and rarely cause adverse reactions, mainly in children predisposed to allergies.

Children are vaccinated against hepatitis A at one year of age, and then after another 6 to 12 months. This scheme provides reliable immunity in 95% of vaccinated people.

Historical information and interesting facts

Epidemic jaundice was first described in ancient times, but the hypothesis of an infectious nature was first formulated by Botkin only in 1888. Further research led in the 1960s to the distinction between fecal-oral viral hepatitis (A) and serum hepatitis (B). Later, other viral hepatitis were identified - C, D, E, etc. Outbreaks of hepatitis A were first described in the 17th-18th centuries.

The fecal-oral mechanism of spread of the virus was discovered only during the Second World War. In 1941-42 Jaundice became a problem for British troops during the war in the Middle East, when the virus put out about 10% of the personnel. From that moment on, in 1943, in-depth research into the problem began in Great Britain and the USA.

The fact of lifelong immunity to infection in those who have once recovered from it has led researchers to the idea that the serum of those who have recovered from hepatitis A can be used for prevention. The effectiveness of using human immunoglobulin (the serum of all adults is believed to contain antibodies to the hepatitis A virus) was demonstrated already in 1945, when the result of immunization of 2.7 thousand American soldiers was an 86% reduction in incidence.

Advantages of the Mama Papa Ya clinic

If a child becomes ill with viral hepatitis A, the Mama Papa Ya network of family clinics offers services for the diagnosis and treatment of this disease. Our advantages:

- a large network of clinic branches in Moscow and other cities;

- affordable prices for services;

- thorough laboratory diagnosis of the disease;

- prescribing modern medications for a speedy recovery;

- consultation with a nutritionist;

- the possibility of vaccinating patients of any age with modern drugs;

- dispensary observation of recovered patients in comfortable conditions, without queues.

To make an appointment, you can call the clinic or leave a request on our website.

Reviews

Good clinic, good doctor!

Raisa Vasilievna can clearly and clearly explain what the problem is. If something is wrong, she speaks about everything directly, not in a veiled way, as other doctors sometimes do. I don’t regret that I ended up with her. Anna

I would like to express my gratitude to the staff of the clinic: Mom, Dad, and me. The clinic has a very friendly atmosphere, a very friendly and cheerful team and highly qualified specialists. Thank you very much! I wish your clinic prosperity.

Anonymous user

Today I had a mole removed on my face from dermatologist I.A. Kodareva. The doctor is very neat! Correct! Thanks a lot! Administrator Yulia Borshchevskaya is friendly and accurately fulfills her duties.

Belova E.M.

Today I was treated at the clinic, I was satisfied with the staff, as well as the gynecologist. Everyone treats patients with respect and attention. Many thanks to them and continued prosperity.

Anonymous user

The Mama Papa Ya clinic in Lyubertsy is very good. The team is friendly and responsive. I recommend this clinic to all my friends. Thanks to all doctors and administrators. I wish the clinic prosperity and many adequate clients.

Iratyev V.V.

We visited the “Mama Papa Ya” Clinic with our child. A consultation with a pediatric cardiologist was needed. I liked the clinic. Good service, doctors. There was no queue, everything was the same price.

Evgeniya

I liked the first visit. They examined me carefully, prescribed additional examinations, and gave me good recommendations. I will continue treatment further; I liked the conditions at the clinic.

Christina

The doctor carefully examined my husband, prescribed an ECG and made a preliminary diagnosis. She gave recommendations on our situation and ordered additional examination. No comments so far. Financial agreements have been met.

Marina Petrovna

I really liked the clinic. Helpful staff. I had an appointment with gynecologist E.A. Mikhailova. I was satisfied, there are more such doctors. Thank you!!!

Olga

Publications in the media

Introduction: Hepatitis A Hepatitis A is a widespread, highly contagious disease caused by the hepatitis A virus (HAV or, in English, HAV for hepatitis A virus) (Fig. 1). In Russia, from 50 thousand (data for 1998) to 183 thousand (data for 1995) cases of the disease are registered annually, but since 1995, thanks to various preventive measures, including vaccination of the population, according to the Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation, the incidence rate has decreased by almost four times. Unlike hepatitis B and C, hepatitis A never occurs in a latent, asymptomatic form and does not become chronic, and the vast majority of its cases end in complete recovery. At the same time, publications devoted to this disease regularly appear in the scientific and popular medical literature, and interest in its prevention and therapy does not wane. Rice. 1. Prevalence of hepatitis A (data for 2003 from the website travelhealth.gov.hk), areas unfavorable for this disease are marked in blue. Hepatitis A: epidemiology Epidemic jaundice was first described in ancient times, but the hypothesis of an infectious nature was first formulated by Botkin only in 1888. Further research led in the 1960s to the distinction between fecal-oral viral hepatitis (A) and serum hepatitis (B). Later, other viral hepatitis were identified - C, D, E, etc. Outbreaks of hepatitis A were first described in the 17th-18th centuries. Non-epidemic, isolated cases of viral hepatitis A have been described as catarrhal jaundice - that is, jaundice accompanied by cold symptoms. A century later, it was proven that epidemic and non-epidemic forms of jaundice are a manifestation of the same infection. The mechanism of spread of the virus was discovered only during the Second World War. In 1941-42 Jaundice became a problem for British troops during the war in the Middle East, when the virus put out about 10% of the personnel. From that moment on, in 1943, in-depth research into the problem began in Great Britain and the USA. The fact of lifelong immunity to infection in those who have once recovered from it has led researchers to the idea that the serum of those who have recovered from hepatitis A can be used for prevention. The effectiveness of using human immunoglobulin (the serum of all adults is believed to contain antibodies to the hepatitis A virus) was demonstrated already in 1945, when the result of immunization of 2.7 thousand American soldiers was an 86% reduction in morbidity (data from the website privivka.ru). The hepatitis A virus is considered the most resistant to external influences: when boiled, its inactivation occurs only after 5 minutes, when treated with chlorine - after 30 minutes, formaldehyde - within 72 hours, 20% ethyl alcohol and strong acids do not lead to inactivation of the virus. Most often, the virus enters the body through the fecal-oral route, that is, by eating contaminated water and food. Usually these are products that cannot be cooked - greens and fruits, either already contaminated with the virus, or washed with water of dubious origin. Less common is the transmission of the virus through contaminated blood and its products, which occurs among drug addicts who share syringes, those who receive blood products or come into contact with blood. This route of transmission is rarely taken into account, although a purely speculative comparison with viral hepatitis B may give an idea of the possible underestimation of the prevalence of hepatitis A. The source of infection is the sick person in the last week of the incubation period (which lasts from 14 to 28 days) and in the first week of the disease . Thus, an apparently healthy person can serve as a source of danger to his environment. The average duration of disability is 35 days. Most cases of the disease begin with symptoms reminiscent of a cold - loss of appetite, general weakness, nausea, vomiting, fever. These symptoms usually do not bother patients much; they continue to work and do not go to doctors. The first symptom that alarms patients is darkening of the urine, which is one of the signs of jaundice. The color of the urine changes from normal straw yellow to the color of dark beer. Another sign of jaundice, which is the first to be noticed by those close to the patient, is the yellowing of the whites of the eyes. The third classic sign of jaundice is discoloration of the stool. However, viral hepatitis A can occur without jaundice, when the only signs of ongoing infection may be nausea, loss of appetite and possibly abdominal pain. The frequency of icteric forms increases with age; jaundice is rare in children under 5 years of age and is an almost obligatory companion to hepatitis A in adults. The most severe clinical forms of viral hepatitis A are cholestatic (literally “stagnation of bile”) and fulminant (fulminant). With the first, the dominant symptoms are severe jaundice, significant enlargement of the liver and severe skin itching, the cause of which is irritation of the nerve receptors of the skin by bile components. Stagnation of bile in this form of viral hepatitis A is caused by significant inflammation of the walls of the bile ducts and the liver as a whole. Despite the more severe course, the prognosis for the cholestatic form of hepatitis A remains favorable. This cannot be said about the fulminate form of hepatitis A, which, fortunately, is quite rare among children and young adults (frequency is a fraction of a percent), but not uncommon in elderly patients (several percent of cases). Death occurs within a few days due to acute liver failure. Countries with moderate endemicity are characterized by a special type of incidence distribution. In rural areas, exposure to the hepatitis A virus occurs in childhood, and immunity is acquired at a younger age. In cities where it is easier to comply with hygienic requirements, a person remains susceptible longer, which, paradoxically, leads to a higher incidence of icteric and sometimes severe forms of hepatitis A in city residents. Thus, city residents traveling to the countryside are also a risk group. Other risk groups are people traveling on business trips and vacations to regions unaffected by hepatitis A; sewer and water supply workers; workers of trade and food enterprises and risk groups for complications and mortality due to hepatitis A: carriers of the hepatitis B and C virus, patients with chronic liver diseases. The situation in the Russian Federation The territory of the Russian Federation is considered unfavorable in terms of the situation with hepatitis A; recently, in 2000 and 2001, another increase in incidence was noted both in the country as a whole and in individual territories, and in general the number of newly registered cases increased by 83 ,5 %. Then a decline in incidence was observed again. This is partly due to the fact that hepatitis A is characterized by wave-like incidence cycles with a period of 5 to 7 years. Large outbreaks of hepatitis A have been reported in various countries. So, in 1988 in Shanghai, this disease affected more than 300 thousand people. The cause was eating raw shellfish. Such a wide spread at once in Russia is impossible, however, outbreaks of hepatitis A occur in various regions of the country. In 2000, nine outbreaks were reported, with a total of approximately 1,000 people affected. In August-September 2001, reports appeared in the media about an outbreak of hepatitis A in several regions of the Russian Federation. Moreover, when assessing the breadth of distribution, it is necessary to remember that for one case of the disease occurring with jaundice, there are at least five cases occurring without jaundice, which are usually not registered and which can be called a “latent form” of hepatitis A (from an interview with M. I. Mikhailov , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the N. F. Gamaleya Research Institute of Epidemiology and Microbiology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow and I. V. Shakhgildyan, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor of the D. I. Ivanovsky Research Institute of Virology of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Moscow, to the journal “Treating Doctor” No. 8, 2001) Hepatitis A: vaccination The question of possible lethality with hepatitis A still remains open. Some researchers completely deny this possibility. According to the website privivka.ru, mortality from hepatitis A ranges from 1% to 30%, with a clear increase in mortality with age, which is associated with an increased likelihood of infection layering on chronic liver disease. A significant proportion of deaths are recorded in patients who are chronic carriers of the hepatitis B virus. There is also a fairly large number of publications describing cases of fulminant hepatitis A (Tabor et al., 1984; Gust et al, 1992). More often, fulminant hepatitis A is registered as a concomitant infection in patients with chronic hepatitis B, C, AIDS, and drug addiction. In addition, the trigger role of the hepatitis A virus in the development of autoimmune hepatitis cannot be ruled out. Superinfection with viral hepatitis A in patients with chronic hepatitis B and C is of particular concern. The fact is that the registered increase in the incidence of hepatitis B, C and HIV infection, occurring in Russia in parallel with the increase in hepatitis A, will lead to an increase in cases of mixed hepatitis and an increase in the number of severe forms of these diseases. For this reason, combined vaccines against hepatitis A and B are very widespread (for example, the Twinrix ™ vaccine, registered in Russia). Hepatitis A virus has low antigenic variability, which is reflected in the existence of only one serotype (Hollinger et al., 2001) (Fig. 2). Some variability of individual antigens of the virus determines its resistance to various antibodies (Nainan et al., 1992; Ping et al., 1992), but does not prevent the creation of highly effective vaccines. Rice. 2. Protein capsid of the hepatitis A virus: green, pink and blue colors indicate variable domains (VP3, VP2 and VP1, respectively). Highly conserved antigenic sites are marked in yellow (from Sanchez et al., 2003). Several vaccines obtained using similar technology and containing an inactivated strain of the virus are approved for use in Russia against hepatitis A itself. This is the Havrix-1440 vaccine, developed in the 90s by GlaxoSmithKline (USA), Vakta (manufactured by Aventis, France) and Hep-A-in-Vac, a domestic drug developed in 1986. 1993 at the M. P. Chumakov Institute of Poliomyelitis and Viral Encephalitis of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences and the industrially produced NP "Vector" (Fig. 3). All these vaccines have passed the necessary tests and can be used for the prevention of hepatitis A ("Treating Doctor" No. 8 for 2001). All vaccines approved for use, as noted by clinicians, are quite effective and have low reactogenicity. Sometimes people who have been vaccinated experience pain and redness at the injection site, less often - a slight increase in temperature and mild malaise; a transient increase in activity liver enzymes are observed extremely rarely.At the same time, drugs against hepatitis A remain very expensive: the price of one dose of the vaccine ranges from 800 to 1000 rubles (Table 1, data for 2008).Fig. 3. Vaccines registered in the Russian Federation against hepatitis A. Table 1. Average prices for vaccines against hepatitis A registered in the Russian Federation. Preventive vaccination is the most effective. During an outbreak of hepatitis A, timely use of vaccines helps limit the spread of infection and is the most effective method of combating hepatitis A. Positive experience in this regard was obtained with the use of the Havrix vaccine to eliminate large outbreaks in Slovakia (Prikazsky et al., 1994); in Alaska (McMahon et al., 1996) and other regions. In response to a single injection of the Havrix vaccine, after one month, antibodies at a protective level are produced in 94-98% of vaccinated people. Repeated vaccine administration provides 99–100% anti-HAV coverage (Hollinger et al., 2007). Data on the duration of post-vaccination immunity indicate that it may persist for at least 10-20 years. Other vaccines containing inactivated hepatitis A virus, used in the world and not used in the Russian Federation, have also been demonstrated to be effective in preventing outbreaks of this disease. An example is the American-made Healive® vaccine, which underwent final testing in 2008 (Shen et al., 2008). Assessment of immunogenic activity is an important step in understanding vaccine prevention. When conducting research, it is necessary to remember the importance of using highly sensitive and specific diagnostic drugs. Thus, in a parallel study of 77 adolescent blood sera 20 days and 1.5 months after a single dose of the Havrix-720 vaccine, anti-HAV in concentrations exceeding 20 mIU/ml were detected in 83.8 and 67.5 % of cases with a domestically produced drug, and with the diagnosticum HAV Total from BIO-RAD, France - in 97.3 and 93.5% of cases (data from the website lvrach.ru). In addition to vaccination with an inactivated virus, vaccination directly with antibodies to hepatitis A, or prophylaxis with immunoglobulin, is also used. When carrying out routine prevention with vaccines, it must be taken into account that the development of immunity after vaccination takes a minimum of two and a maximum of four weeks. Immunization with immunoglobulin can be used for emergency prevention purposes, as it provides immediate protection against infection. At the same time, immunoglobulin does not provide long-term protection, so immunoglobulin is often administered simultaneously with the vaccine. WHO position on hepatitis A vaccines “All currently available hepatitis A vaccines are of good quality and comply with the above WHO recommendations. However, they are not licensed for use in children under one year of age. The effectiveness of vaccines in children under one year of age varies due to the effects of maternal antibodies. Although available vaccines induce long-term protection when given in two doses 6-18 months apart, a high degree of immunity is acquired after the first dose. Studies aimed at studying the duration of immunity after one dose of the vaccine are strongly encouraged. Planning for large-scale hepatitis A immunization programs should include careful analysis of the cost-effectiveness and sustainability of different hepatitis A prevention strategies, as well as an assessment of the likely long-term epidemiological consequences of vaccination at different coverage levels. In countries with high endemicity, exposure to HAV is almost universal before the age of 10 years. In such countries, clinical hepatitis A is usually a minor public health problem and large-scale immunization efforts against the disease should not be undertaken. In developed countries with low endemicity and high incidence in selected high-risk populations, immunization of such populations against hepatitis A may be recommended. High-risk groups include injecting drug users, homosexuals, people traveling to high-risk areas, and certain ethnic or religious groups. However, it should be noted that immunization programs targeting selected high-risk groups may have little impact on national hepatitis A incidence rates. In areas of moderate endemicity, where transmission is predominantly person-to-person (often with periodic outbreaks), hepatitis A can be controlled through large-scale immunization programs. Recommendations for immunization against hepatitis A in an outbreak setting depend on the epidemiology of hepatitis A in a given community and the ability to quickly implement a large-scale immunization program. The use of hepatitis A vaccine to control large outbreaks has been most successful in small, dense communities when vaccination is initiated early in the outbreak and high coverage is achieved across a wide age group. Vaccination efforts must be accompanied by health education and improved sanitation. Although the disease burden associated with hepatitis A is significant in many countries, the decision to include hepatitis A vaccine in routine childhood immunization programs must be made in the context of the full range of available immunization inputs. This includes vaccines against hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae b, rubella and yellow fever, and, in the near future, pneumococcal vaccines, which together are likely to lead to more significant results in addressing public health problems.” Conclusion In conclusion, it can be said that hepatitis A cannot currently be considered a serious clinical problem. As a result of many years of work of researchers and clinicians around the world, the strategies for prevention and combating this disease are finally clear, and numerous modern vaccines are very effective. Nevertheless, it should be noted the need to develop cheaper methods for the production of vaccines against hepatitis A, since some authors note the economic inefficiency of universal preventive vaccination (Anonychuk et al., 2008; Bauch et al., 2007). In particular, this statement can be attributed to the Russian Federation, where only one vaccine of domestic production is applied. Literature: 1. Anonychuk AM, Tricco AC, Bauch CT, Pham B., Gilca V., Duval B., John-Baptiste A., Wo G., Krahn M. Cost-Effectivens of Hepatitis a Vaccine: A Systematic Revie Revie W. To Explore The Effect of Methodological Quality On the Economic Attractivence of Vaccination Strategies. Pharmacoeconomics. 2008; 26 (1): 17 - 32. 2. Bauch CT, Anonychuk am, Pham Bz, Gilca V, Duval B, Krahn MD. COST-UTILITY OF UNIVERSAL HEPATITIS A Vaccination in Canada. Vaccine. 2007; 25 (51): 8536-8548. 3. Blaine Hollinger F., Bell B., Levy-Bruhl D., Shouval D., Wiersma S., Van Damme P. Hepatitis a and B Vaccination and Public Health. J. viral. Hepat. 2007; 14 SUPPL 1: 1-5. 4. Gist ID Epidemiological Patterns of Hepatitis a in Different Parts of the World. Vaccine, Volume 10, Supplement 1, 1992; S56-S58. 5. Hollinger, FB, and SU Emerson. 2001. Hepatis a virus, p. 799–840. In DM KNIPE, PM Howley, De Griffin, Ra Lamb, Ma Martin, B. Roizman, and Se Straus (Ed.), Fields Virology, 4th Ed., Vol. 1. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA. 6. McMahon BJ, BELLER M., Williams J., Schloss M., Tanttila H., Bulkow L. A Program to Control An outbreak of hepatitis a in alska by using an inactted hepatitis a var. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 1996; 150 (7): 733 - 739. 7. Nainan OV, Brinton Ma, Margolis HS Identification of Amino Acids Located in the Antibody Sites of Human Hepatitis a Virus. Virology 1992; 191: 984-987. 8. Príkazskutch v, Oleár v, Cernoch a, Safary a, André Fe. Interruption of an outbreak of hepatitis a in two villages by vaccination. J. Med. Virol. 1994; 44 (4): 457-459. 9. Ping L.-H., Lemon SM Antigenic Structure of Human Hepatis a Virus Defined by Analysis of Escape Mutants Selected Murine Monoclonal Antibodies. J. Virol. 1992 66: 2208-2216. 10. Sanchez G., Bosch A., Pinto Rm Genome VariaBility and Capsid Structural Constraints of Hepatitis a Virus. Journal of Virology 2003; 452-459. 11. Shen yg, gu xj, zhou jh Protective Effect of Inactivated Hepatis a Vaccine Against the outbreak of hepatitis a in an open rural community. World J. Gastroenterol 2008; 14 (17): 2771-2775. 12. Tabor E., Snoy P., Jackson DR, Schaff Z., Blatt PM, Gerety RJ Additional Evience FORE THE ONE AGENT OF HUMAN Non-A, Non-B Hepatitis. Transmission and Passage Studies in Chimpanzees. Transfusion 1984; 24 (3): 224 - 230.

Internet sources: 1. World Health Organization 2. US Food and Drug Administration 3. EMedicineHealth 4. AboutHepatitis 5. Ministry of Health and Social Development of the Russian Federation 6. HepatituNET 7. Vaccination.RU 8. “Attending Doctor” 9. TravelHealth