Esophageal adenocarcinoma is a form of cancer in which cancer cells develop from glandular, mucus-producing cells. The disease usually develops in the lower third, in the area of the gastroesophageal junction.

Esophageal cancer is one of the most aggressive malignant neoplasms and ranks eighth in the structure of mortality in the world. The most common morphological forms are squamous cell carcinoma (95%) and adenocarcinoma (3%). Extremely rare are carcinosarcoma, small cell carcinoma and melanoma. According to calculations by Rosstat of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, the incidence among men and women is 7.6 and 2.4 cases per 100 thousand population, respectively.

- Risk factors

- Classification

- Clinical picture and symptoms

- Diagnostics

- Treatment

- After treatment

- Forecast

Adenocarcinoma is considered one of the rapidly spreading forms of esophageal cancer in North America and Europe, while squamous cell carcinoma predominates in developing countries. This is due to the implementation of risk factors for the development of these forms of esophageal cancer.

Risk factors

- Barrett's esophagus is a disease in which the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by glandular cells. This process is called intestinal metaplasia and develops as a result of chronic aggressive effects of gastric juice on the esophageal mucosa in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and hiatal hernia.

- Obesity.

- Cardiac achalasia and cardiospasm.

Photo. Endoscopic picture of Barrett's esophagus

Classification

Classification of esophageal adenocarcinoma is carried out according to the criteria of the international classification of malignant neoplasms TNM (8th revision):

T

- Tis carcinoma in situ/high grade dysplasia;

- T1 tumor growth into the lamina propria or submucosal layer: T1a lamina propria or muscularis lamina of the mucosa;

- T1b submucosal layer.

- T4a pleura, peritoneum, pericardium, diaphragm;

N

- N0 no metastases in regional lymph nodes;

- N1 damage to 1-2 regional lymph nodes;

- N2 damage to 3-6 regional lymph nodes;

- N3 damage to 7 or more regional lymph nodes.

M

- M1 presence of distant metastases.

The following groups of lymph nodes are regional:

- disgraced,

- internal jugular,

- upper and lower cervical,

- cervical paraesophageal,

- supraclavicular (bilateral),

- pretracheal (bilateral),

- lymph nodes of the lung root (bilateral),

- upper paraesophageal (above v. azygos),

- bifurcation,

- lower paraesophageal (below v. azygos),

- posterior mediastinal,

- diaphragmatic,

- perigastric (right and left cardiac, lymph nodes along the lesser curvature of the stomach, along the greater curvature of the stomach, suprapyloric, infrapyloric, lymph nodes along the left gastric artery).

Damage to the celiac lymph nodes is not a contraindication to chemoradiation therapy or the issue of surgical treatment.

Degree of tumor differentiation

GX – the degree of tumor differentiation cannot be determined;

G1 – well-differentiated tumor;

G2 – moderately differentiated tumor;

G3 – poorly differentiated tumor;

G4 – undifferentiated tumor.

In the classification of esophageal adenocarcinoma, cardioesophageal cancer , i.e. cancer developing in the area of the esophagogastric junction and cardia.

Sievert classification

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction, according to Sievert's classification, is divided into 3 types:

Type I - adenocarcinoma of the distal esophagus (often associated with Barrett's esophagus), the center of the tumor is located within 1-5 cm above the cardia (dentate line);

Type II – true adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction (true cancer of the cardia), the center of the tumor is located within 1 cm above and 2 cm below the cardia (dentate line);

Type III - cancer with the localization of the main mass of the tumor in the subcardial part of the stomach within 2-5 cm below the dentate line and possible involvement of the distal parts of the esophagus.

Tumors of the esophagogastric junction of types I and II are subject to treatment according to algorithms corresponding to the RP. Type III tumors are treated according to algorithms corresponding to stomach cancer.

Classification of cancer of the esophagogastric junction according to Siewert

Classification of esophageal adenocarcinoma by stages

Esophagus

| Schematic representation of the esophagus. 1 - pharynx, 2 - superior narrowing of the esophagus, 3 - cervical esophagus, 4 - aortic narrowing of the esophagus, 5 - thoracic esophagus, 6 - diaphragmatic narrowing of the esophagus, 7 - diaphragm, 8 - cardia of the stomach, 9 - abdominal esophagus ( Shishko V.I., Petrulevich Yu.Ya.) |

The esophagus

(lat.

œsóphagus

) is part of the digestive canal located between the pharynx and stomach. The shape of the esophagus is a hollow muscular tube, flattened in the anteroposterior direction.

The length of the esophagus of an adult is approximately 25–30 cm. The esophagus begins in the neck at the level of the VI–VII cervical vertebrae, then passes through the chest cavity in the mediastinum and ends in the abdominal cavity, at the level of the X–XI thoracic vertebrae.

The upper esophageal sphincter is located at the border of the pharynx and esophagus. Its main function is to pass lumps of food and liquid from the pharynx into the esophagus, while preventing them from moving back and protecting the esophagus from air entering during breathing and the trachea from food entry. It is a thickening of the circular layer of striated muscles, the fibers of which have a thickness of 2.3–3 mm and which are located at an angle of 33–45° relative to the longitudinal axis of the esophagus. The length of the thickening on the front side is 25–30 mm, on the back side 20–25 mm. Dimensions of the upper esophageal sphincter: about 23 mm in diameter and 17 mm in the anteroposterior direction. The distance from the incisors to the upper border of the upper esophageal sphincter is 16 cm in men and 14 cm in women.

The normal weight of the esophagus of a “conditional person” (with a body weight of 70 kg) is 40 g.

The esophagus is separated from the stomach by the lower esophageal sphincter (synonymous with cardiac sphincter). The lower esophageal sphincter is a valve that, on the one hand, allows lumps of food and liquid to pass from the esophagus into the stomach, and, on the other hand, prevents aggressive stomach contents from entering the esophagus.

The esophagus has three permanent narrowings:

- upper

or

pharyngoesophageal

(lat.

constrictio pharyngoesophagealis

) - aortic

or

bronchoaortic

(lat.

constrictio bronhoaortica

) - diaphragmatic

(lat.

constrictio diaphragmatica

)

The upper part of the esophagus (approximately one third) is formed by striated voluntary muscle tissue, which below is gradually replaced by smooth muscle, involuntary.

The smooth muscles of the esophagus have two layers: the outer - longitudinal and the inner - circular. Normal acidity in the esophagus is slightly acidic and ranges from 6.0 to 7.0 pH.

The blood supply to the esophagus with arterial blood comes from the branches of the subclavian artery, thyroid artery, intercostal arteries, esophageal branches of the aorta, bronchial arteries, branches of the phrenic and gastric arteries. Venous outflow occurs through the veins - the lower thyroid, pericardial, posterior mediastinum and diaphragmatic. The veins of the abdominal part of the esophagus are directly connected to the veins of the stomach and the portal vein; they carry out an anastomosis between the portal and vena cava systems.

Lymphatic vessels of the esophagus drain into the deep lymph nodes of the neck, posterior mediastinum and lymph nodes of the stomach. Some of the lymphatic vessels of the esophagus open directly into the thoracic duct.

Innervation of the esophagus is provided by the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous systems. The nerve fibers of both systems on the surface of the esophagus form the anterior and posterior plexuses. The cervical part of the esophagus is innervated by the recurrent nerves (Ionov A.Yu. et al.).

Topography of the esophagus

The figure below (a - front view of the esophagus, b - rear view) shows: 1 - pars cervicalis oesophagi; 2 - n. laryngeus recurrens sin.; 3 - trachea; 4 - n. vagus sin.; 5 - arcus aortae; 6 - bronchus principatis sin.; 7 - aorta thoracica; 8 - pars thoracica oesophagi; 9 - pars abdominalis oesophagi; 10 - ventriculus; 11 - diaphragma; 12 - v. azygos; 13 - plexus oesophageus; 14 - n. vagus dext.; 15 - n. laryngeus recurrens dext. et rami oesophagei; 16 - tunica mucosa (Storonova O.A., Trukhmanov A.S.).

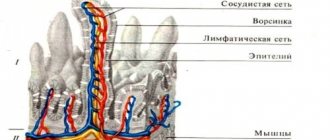

The structure of the esophageal wall

On a cross-section, the lumen of the esophagus appears as a transverse slit in the cervical part (due to pressure from the trachea), in the thoracic part the lumen has a round or stellate shape.

The wall of the esophagus consists of adventitia, muscular, submucosal layers and mucosa. When not stretched, the mucous membrane gathers into longitudinal folds. Longitudinal folding promotes the movement of fluid along the esophagus along the grooves between the folds and stretching of the esophagus during the passage of dense lumps of food. This is also facilitated by the loose submucosal layer, due to which the mucous membrane acquires greater mobility. A layer of smooth muscle fibers of the mucous membrane itself is involved in the formation of folds.

| Cross section of the esophagus. 1 – mucous membrane of the esophagus (a – epithelium, b – muscular lamina of the mucosa, c – lamina propria of the mucosa), 2 – submucosa, 3 – glands of the esophagus, 4 – muscular lining of the esophagus (a – circular layer, b – longitudinal layer), 5 – adventitia (Shishko V.I., Petrulevich Yu.Ya.) |

The mucosal epithelium is a multilayered squamous non-keratinizing epithelium; in old age, its surface cells may undergo keratinization. The epithelial layer contains 20-25 cell layers. It also contains intraepithelial lymphocytes, dendritic antigen-presenting cells. The lamina propria is formed by loose fibrous connective tissue, protruding into the epithelium through high papillae. It contains a cluster of lymphocytes, lymph nodes and the end sections of the cardiac glands of the esophagus (similar to the cardiac glands of the stomach). The glands are simple tubular, branched, in their terminal sections there are cells that produce mucins, parietal cells, endocrine (enterochromaffin and enterochromaffin-like) cells that synthesize serotonin. The cardiac glands of the esophagus are represented by two groups. One group of glands lies at the level of the cricoid cartilage of the larynx and the fifth ring of the trachea, the second group is in the lower part of the esophagus. The structure and function of the cardiac glands of the esophagus are of interest, because it is in their locations that diverticula, cysts, ulcers and tumors of the esophagus often form. The muscular plate of the esophageal mucosa consists of bundles of smooth muscle cells located along it, surrounded by a network of elastic fibers. It plays an important role in carrying food through the esophagus and in protecting its inner surface from damage by sharp bodies if they enter the esophagus.

The submucosa is formed by fibrous connective tissue with a high content of elastic fibers and ensures the mobility of the mucous membrane. It contains lymphocytes, lymph nodes, elements of the submucosal nerve plexus and the end sections of the alveolar-tubular glands of the esophagus. Their ampulla-shaped dilated ducts bring mucus to the surface of the epithelium, which promotes the movement of the food bolus and contains an antibacterial substance - lysozyme, as well as bicarbonate ions that protect the epithelium from acids.

The muscles of the esophagus consist of an external longitudinal (dilating) and internal circular (constricting) layers. The intermuscular autonomic plexus is located in the esophagus. In the upper third of the esophagus there is striated muscle, in the lower third there is smooth muscle, and in the middle part there is a gradual replacement of striated muscle fibers with smooth ones. These features can serve as guidelines for determining the level of the esophagus on a histological section. The thickening of the inner layer of the muscular layer at the level of the cricoid cartilage forms the upper sphincter of the esophagus, and the thickening of this layer at the level of the transition of the esophagus to the stomach forms the lower sphincter. When it spasms, obstruction of the esophagus can occur; when vomiting, the sphincter gapes.

The adventitia, which surrounds the outside of the esophagus, consists of loose connective tissue through which the esophagus is connected to the surrounding organs. The looseness of this membrane allows the esophagus to change the size of its transverse diameter as food passes through. The abdominal section of the esophagus is covered with peritoneum (Shishko V.I., Petrulevich Yu.Ya.).

Factor of aggression and protection of the esophageal mucosa

With gastroesophageal reflux, both physiological and pathological, refluxate containing hydrochloric acid, pepsin, bile acids, lysolycetin, entering the lumen of the esophagus, has a damaging effect on its mucous membrane.

The integrity of the mucous membrane of the esophagus is determined by the balance between aggressive factors and the ability of the mucous membrane to withstand the damaging effects of the refluxed stomach contents. The first barrier that has a cytoprotective effect is the mucus layer covering the epithelium of the esophagus and containing mucin. The resistance of the mucous membrane to damage is determined by pre-epithelial, epithelial and post-epithelial protective factors, and in vivo

in patients, it is possible to evaluate the state of only pre-epithelial protective factors, including the secretion of the salivary glands, the mucus layer and the secretion of the glands of the submucosal base of the esophagus.

The intrinsic deep glands of the esophagus secrete mucins, non-mucin proteins, bicarbonates and non-bicarbonate buffers, prostaglandin E2, epidermal growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha and, in part, serous secretions. The main component that is part of the secretions of all mucous glands is mucins (from the Latin mucus

- mucus), which is a mucoprotein belonging to the family of high molecular weight glycoproteins containing acidic polysaccharides. Mucins have a gel-like consistency.

The epithelial level of protection consists of structural (cell membranes, intercellular junctional complexes) and functional (epithelial transport of Na+/H+, Na+-dependent CI-/HLO-3; intracellular and extracellular buffer systems; cell proliferation and differentiation) components. The epithelium of the esophagus and the supradiaphragmatic part of the lower esophageal sphincter is multilayered, flat, non-keratinizing. Postepithelial protective mechanisms are the blood supply to the mucous membrane and the acid-base state of the tissue.

An integrative indicator that combines all mechanisms for restoring intraesophageal pH is called esophageal clearance, which is defined as the time of elimination of a chemical irritant from the esophageal cavity. It is achieved through a combination of 4 factors. The first is the motor activity of the esophagus, represented by primary (the act of swallowing initiates the appearance of a peristaltic wave) and secondary peristalsis, observed in the absence of swallowing, which develops in response to stretching of the esophagus and/or a shift in intraluminal pH towards low values. The second is the force of gravity, which accelerates the return of refluxate to the stomach when the patient is in an upright position. The third is adequate production of saliva, which contains bicarbonates that neutralize the acidic contents. Finally, the fourth, extremely important factor in esophageal clearance is the synthesis of mucin by the glands of the submucosa of the esophageal mucosa (Storonova O.A. et al.).

Esophagus in children

At the beginning of intrauterine development, the esophagus has the appearance of a tube, the lumen of which is filled due to the proliferation of cell mass.

At 3–4 months of fetal life, glands are formed, which begin to actively secrete. This promotes the formation of a lumen in the esophagus. Violation of the recanalization process is the cause of congenital narrowings and strictures of the esophagus. In newborns, the esophagus is a spindle-shaped muscular tube lined with mucous membrane on the inside. The entrance to the esophagus is located at the level of the disc between the III and IV cervical vertebrae, by 2 years - at the level of IV-V cervical vertebrae, at 12 years - at the level of VI-VII vertebrae. The length of the esophagus in a newborn is 10–12 cm, at the age of 5 years - 16 cm; its width in a newborn is 7–8 mm, by 1 year - 1 cm and by 12 years - 1.5 cm (Bokonbaeva S.D. et al.).

In newborn children, the length of the esophagus is 10 cm and is about half the length of the body (in adults - about a quarter). In five-year-olds, the length of the esophagus is 16 cm, in ten-year-olds it is 18 cm. The shape of the esophagus in young children is funnel-shaped, its mucous membrane is rich in blood vessels, muscle tissue, glands of the mucous membrane and elastic tissue are not sufficiently developed.

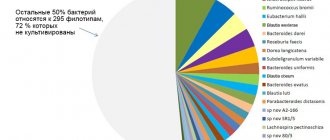

Microbiota of the esophagus

The microbiota enters the esophagus mainly with saliva. During esophageal biopsy, representatives of the following genera and families are most often isolated: Streptococcus, Rothia, Veillonellaceae, Granulicatella, Prevotella

.

Spectrum and frequency of occurrence of microorganisms in the mucous membranes of the esophagus, stomach and duodenum of healthy people (Julai G.S. et al.)

Some diseases and conditions of the esophagus

Some stomach diseases and syndromes (see):

| Reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus ( gastroesophageal reflux) is the cause of many diseases of the esophagus. |

- gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- reflux esophagitis

- esophagitis

- eosinophilic esophagitis

- Barrett's esophagus

- functional heartburn

- hypersensitive esophagus (esophagus hypersensitivity to reflux)

- esophageal carcinoma

- hiatal hernia (HH)

- esophagospasm

- “Nutcracker esophagus” (segmental spasm of the esophagus)

Some symptoms that may be associated with esophageal diseases:

- heartburn

- chest pain

- dysphagia

- odynophagia

- globus pharyngeus ("lump in throat")

Publications for Health Professionals

- Rapoport S.I., Lakshin A.A., Rakitin B.V., Trifonov M.M. pH-metry of the esophagus and stomach in diseases of the upper digestive tract / Ed. Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences F.I. Komarova. – M.: ID MEDPRACTIKA-M. — 2005. – p. 208.

- Bordin D.S., Valitova E.R. Methodology and clinical significance of esophageal manometry (Methodological recommendations No. 50) / Ed. Doctor of Medical Sciences, Prof. L.B. Lazebnik. – M.: Publishing House “Medpraktika-M”. - 2009. - 24 p.

- Golochevskaya V.S. Esophageal pain: do we know how to recognize them?

- Storonova O.A., Trukhmanov A.S. Methods for studying the motor function of the esophagus. A manual for postgraduate education / Ed. Academician RAMS, prof. V.T. Ivashkina. – M. – 2011. – 36 p.

- Trukhmanov A.S., Kaibysheva V.O. pH-impedancemetry of the esophagus. A manual for doctors / Ed. acad. RAMS, prof. V.T. Ivashkina - M.: Publishing House "Medpraktika-M", 2013. 32 p.

- Bordin D.S., Yanova O.B., Valitova E.R. Methodology and clinical significance of impedance pH monitoring. Guidelines. – M.: Publishing House “Medpraktika-M”. 2013. 27 p.

- Shishko V.I., Petrulevich Yu.Ya. GERD: anatomical and physiological features of the esophagus, risk factors and development mechanisms (literature review, part 1) // Journal of the Grodno State Medical University. 2015, no. 1, pp. 19–25.

- Storonova O.A., Trukhmanov A.S. 24-hour pH impedance measurement. Differential diagnosis of functional diseases of the esophagus. A manual for doctors / Ed. acad. RAS, prof. V.T. Ivashkina - M.: Publishing House "MEDPRACTIKA-M", 2022. 32 p.

On the website in the “Literature” section there is a subsection “Diseases of the esophagus”, which contains a large number of publications for healthcare professionals on diseases of the esophagus, their diagnosis and treatment.

Lecture for medical university students, which touches on the anatomy of the esophagus (video)

Lebedeva A.V. Acid-dependent diseases of the gastrointestinal tract

Patient Materials

The GastroScan.ru website contains materials for patients on various aspects of gastroenterology:

- “Advice from doctors” in the “Patients” section of the site

- “Popular gastroenterology” in the “Literature” section

- “Popular gastroenterology” in the “Video” section

Back to section

Clinical picture and symptoms

Early stages of esophageal adenocarcinoma in the absence of narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus are often asymptomatic and are an incidental finding during endoscopic examination in connection with other diseases of the esophagus or examination. Separately, attention should be paid to conducting routine dynamic endoscopic examination in patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett's esophagus, who are at risk for developing esophageal adenocarcinoma.

With the development of a tumor that narrows the lumen of the esophagus (usually with a narrowing of less than 15 mm), the main clinical manifestation is dysphagia syndrome, which includes:

- Difficulty swallowing food, food getting stuck in the esophagus (dysphagia);

- Unmotivated weight loss due to decreased nutrition;

- Regurgitation (regurgitation) of eaten food;

- Feeling of pressure and discomfort in the chest;

- Pain when swallowing food (rare);

- Drooling (rare).

Signs of a common disease include:

- Progressive dysphagia (from difficulty swallowing solid foods to the inability to swallow liquids and saliva);

- Significant decrease in body weight up to the development of cachexia (extreme exhaustion);

- Fever;

- Bone pain;

- Dyspnea;

- Substernal pain or back pain;

- Signs of bleeding from the gastrointestinal tract (vomiting blood, black stools (melena), anemia in a general blood test).

Ultrasound picture of the stomach and esophagus

In order to be well versed in the results of an ultrasound scan of the stomach and esophagus, it is necessary, first of all, to know the anatomy of these organs, which we will briefly present below.

Anatomy of the stomach and esophagus

The esophagus is a hollow tube that extends from the pharynx to the stomach. The esophagus is conventionally divided into three parts - the upper, middle and lower thirds, and the boundaries of each part are physiological narrowings of the organ. Thus, the upper third of the esophagus begins from the pharynx and continues to the level of the second physiological narrowing, which lies at the level of the division of the trachea into the right and left main bronchus. The middle third of the esophagus (thoracic part) continues from the second physiological narrowing to the level of the diaphragm. Finally, the lower third of the esophagus (the abdominal part) extends from the level of the diaphragm to its connection with the stomach.

The stomach is located in the upper abdomen between the esophagus and duodenum (see Figure 1). The area where the stomach connects to the esophagus is called the cardiac part (or simply cardia), the upper part is the fundus of the stomach. Below the bottom is the body of the stomach, which passes into the pyloric (pyloric) part. The pyloric part, in turn, consists of the pyloric cave (sinus) and the pyloric canal. The cardia, fundus and body of the stomach form the digestive sac, and the cave and the pyloric canal form the evacuation canal.

In the stomach itself, there are anterior and posterior walls. The anterior wall of the stomach is in contact with the diaphragm, the anterior abdominal wall and the lower part of the liver. The posterior wall of the stomach is adjacent to the aorta, pancreas, spleen, upper pole of the left kidney and left adrenal gland, partially to the diaphragm and transverse colon. The lesser curvature is located on the anterior wall of the stomach, and the greater curvature is located on the posterior wall. The shape of the stomach varies depending on age, gender, its location, filling, and functional state. However, normally the stomach most often has the shape of either a horn or a hook. The size of the stomach also varies - its length is normally 20 - 25 cm, width - 12 - 14 cm, length of the lesser curvature - 18 - 19 cm, length of the greater curvature - 45 – 56 cm, wall thickness – 2 – 5 cm, and capacity – 1.5 – 3 liters.

Ultrasound indicators of the stomach and esophagus

The esophagus is visible in the form of a tube with characteristic physiological narrowings. Normally, the tube should have a uniform wall, without bulges, fluid accumulations, thickenings, etc. The wall of the esophagus has a thickness of about 6 mm. The abdominal part of the esophagus is clearly visualized, visible as a tube with an outer hypoechoic muscle layer and an inner hyperechoic mucous membrane. The diameter of the abdominal esophagus must be measured, which is normally 5–10 mm in children and adolescents, and more than 10.5 mm in adults. When a peristaltic wave or food passes, the lumen of the esophagus opens by 1–2 mm. The stomach is scanned on an empty stomach, without a water-siphon test. During the scan, the position and shape of the stomach, the fluid content on an empty stomach, the condition of the walls, peristalsis and evacuation capacity must be determined. You should know that in a lying position it is possible to fully see the entire stomach only in thin patients, and in people with a heavy build or overweight it is possible to visualize only the outlet of the stomach and its connection with the duodenum. The connection between the stomach and intestines has a characteristic “hourglass” appearance.

With the patient lying on his side, one can also examine the lesser and greater curvature, the pyloric part of the stomach, and the fundus of the stomach. Normally, the stomach is located under the lower edge of the liver. The position of the stomach is determined by the lower border of the greater curvature and the pylorus, which is clearly visible on ultrasound and can have a different position, depending on the posture and physique of the patient. In people with a normal (normosthenic) physique, in the lying position the pylorus is usually located above the navel, and in the standing position it lowers by about 3 - 5 cm. The pylorus is usually visible on ultrasound in the form of a round formation with a diameter of 2 - 2.5 cm with walls 4 - 5 cm thick. 5 mm, with a hypoechoic peripheral rim and an echogenic central part. The peripheral rim reflects the wall of the stomach, and the central part reflects the folds of the mucous membrane. During the study, due to peristaltic contractions, the shape of the stomach and the thickness of its walls are constantly changing. During ultrasound, various parameters of an empty stomach are measured, which are normally the following:

- outer cross-sectional diameter of the gastric outlet – 14 – 21 mm;

- wall thickness of the gastric outlet – 4 – 5 mm;

- the distance between the walls of the outlet of the stomach is 5 – 10 mm;

- length of the gastric outlet – 42.8 ± 1.9 mm;

- image coefficient (ratio of wall thickness to the minimum distance between walls) – 0.4 – 1.0;

- the lower border of the greater curvature of the stomach in the supine position is 63.7 ± 3.9 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus of the stomach in the supine position is 67.5 ± 5.4 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus of the stomach in standing and sitting positions is 46.2 ± 3.6 mm above the navel;

- the lower border of the greater curvature of the stomach in standing and sitting positions is 37.6 ± 2.9 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus in the supine, standing and sitting position - 30 - 40 mm to the right of the midline of the abdomen;

- angle of the stomach – 45 – 70 o.

Normally, on an empty stomach, the stomach can contain up to 40 ml of liquid, which indicates a normal evacuation function. If the liquid in the stomach contains more than 40 ml, this indicates a violation of the evacuation function, which may be caused by gastric atony, pyloric stenosis, pyloric spasm. After filling the stomach with water, when performing an ultrasound with a water-siphon test, the organ takes on an oval-elongated or pear-shaped shape. Stretching the stomach with water allows you to study in more detail the uniformity and thickness of the walls, as well as evaluate peristalsis. At the same time, pay attention to the size and shape of the stomach cavity, monitor the depth, frequency and periodicity of peristalsis waves. After taking the liquid, an ultrasound scan shows anechoic water in the stomach, hyperechoic moving air bubbles in it, as well as three layers of the organ wall. The inner mucosa and outer serous membranes form, as it were, two hyperechoic lines, between which lies the hypoechoic contents of the muscular layer. The normal parameters of a water-filled stomach, measured during ultrasound, are as follows:

- the lower border of the greater curvature of the stomach in the supine position is 33.1 ± 3.5 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus of the stomach in the supine position is 45.6 ± 3.8 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus of the stomach in standing and sitting positions is 24.7 ± 3.1 mm above the navel;

- the pylorus in the supine, standing and sitting position - 40 - 50 mm to the right of the midline of the abdomen.

If, according to ultrasound data, a thickening of the wall of an empty or water-filled stomach of more than 5 mm is detected, then the localization of such an area, its maximum thickness, the shape and outline of the external and internal contours, the distance between the walls in the area of this area, the presence of layering of the wall, its uniformity and echogenicity. It is also necessary to determine the presence of free or encysted fluid, gas near the affected area, pain or sensitivity when pressing the sensor on the skin over the pathological focus.

Normal ultrasound of the stomach

The conclusion of an ultrasound of a normal unaffected stomach must indicate that there is no pathological symptom of the affected organ, the accumulation of free fluid is not detected. The conclusion of an ultrasound of a normal esophagus indicates the thickness of its walls, the absence of bulges, neoplasms and signs of an inflammatory process.

Diagnosis of the disease

The optimal examination plan for making a diagnosis, determining the clinical stage and developing a treatment plan should include the following procedures:

- The main diagnostic method is esophagogastroduodenoscopy. It allows you to obtain material for morphological confirmation of the diagnosis, as well as assess the extent of the primary tumor in the esophagus. In order to increase the information content of the method, techniques such as chromoendoscopy, endoscopy in a narrow spectral beam of light, and autofluorescence can currently be used.

- Endosonography (Endo-ultrasound) is the most informative method in assessing the depth of tumor invasion into the wall of the esophagus (T symbol). It also allows you to assess the condition of regional lymph collectors with high accuracy (sensitivity 0.8 and specificity 0.7). For more accurate preoperative staging and determination of treatment tactics, it is possible to perform a puncture biopsy of the mediastinal lymph nodes.

- X-ray contrast examination of the esophagus.

X-ray of the esophagus with barium in a patient with esophageal cancer

- CT scan of the chest and abdomen with intravenous contrast. Performed to assess the condition of regional lymph nodes and exclude distant metastases. Compared to endo-ultrasound, it has lower sensitivity (0.5) but greater specificity (0.83) in the diagnosis of regional metastases. For distant metastases, this figure is 0.52 and 0.91, respectively.

- Combined positron emission computed tomography with 18F deoxyglucose (PET/CT) is not very informative for determining T and N status. But it demonstrates higher sensitivity and specificity in detecting distant metastases compared to CT. PET/CT is recommended if the patient does not have distant metastases according to CT data (M1).

- Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is performed to exclude invasion into the trachea and main bronchi for tumors of the esophagus located at or above its bifurcation.

, additional functional tests are performed according to indications : echocardiography, Holter monitoring, pulmonary function testing, vascular ultrasound, examination of the blood coagulation system, urine tests, consultations with medical specialists (cardiologist, endocrinologist, neurologist, etc.) .P.).

Esophageal strictures

Esophageal stricture is a pathological narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus as a result of inflammation, fibrous or dysplastic changes in the area of the narrowing itself.

Globally, esophageal strictures are divided into benign (80%) and malignant (20%). The vast majority of benign strictures are the result of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) with the development of reflux esophagitis and subsequent cicatricial changes. These strictures usually occur in the distal esophagus within 4 cm of the esophagogastric junction. Concomitant inflammation of the mucous membrane and submucosal fibrosis create the appearance of inflammation and gradual narrowing of the lumen.

The most common cause of malignant esophageal stricture is Barrett's esophagus with subsequent malignant transformation, most often into adenocarcinoma.

1. By nature:

- Benign: peptic, burn (thermal and chemical), traumatic;

- Malignant.

2. According to the length, esophageal strictures are divided into:

- short (length less than 5 cm);

- extended (length is more than 5 cm);

- subtotal (only the thoracic esophagus is affected);

- total (all parts of the esophagus are affected).

3. Endoscopic classification of esophageal narrowings:

- I degree - narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus to 9–11 mm;

- II degree - narrowing of the lumen to 6–8 mm;

- III degree - narrowing of the lumen 3–5 mm;

- IV degree - the lumen of the esophagus is narrowed to 1-2 mm or completely blocked.

4. According to the degree of chemical burn of the esophagus:

- Mild degree - damage to the superficial layers of the epithelium of the mucous membrane with subsequent inflammation. Completely reversible process;

- Medium degree - damage to the entire thickness of the mucosa with involvement of the submucosal layer. Necrotic-ulcerative esophagitis develops with the formation of a cicatricial stricture of the esophagus;

- Severe degree - the wall of the esophagus is affected to its full depth, a violation of the integrity of the wall of the esophagus (perforation) with the involvement of paraesophageal tissue and neighboring structures (pleura, pericardium) is possible.

Regardless of the nature of the stricture, the clinical picture usually includes one or more combined symptoms:

- dysphagia,

- disturbance of appetite and nutrition,

- odynophagia,

- chest pain,

- weight loss.

Of all the above symptoms, progressive dysphagia is the most common. In benign strictures, dysphagia develops slowly and unnoticed over several years, while in malignant strictures, dysphagia progresses over weeks or months. A thorough history can help determine the cause of dysphagia, but keep in mind that 25% of patients with peptic strictures have no previous history of heartburn or other symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy and fluoroscopy of the esophagus and esophagogastric junction using water-soluble contrast are the basis of the initial examination and diagnosis of esophageal stricture.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy makes it possible not only to establish the fact of narrowing of the esophagus, but also allows you to visualize the esophageal mucosa and collect material for further histological examination. The latter is especially important when determining the nature of the stricture. Fluoroscopy, in turn, is needed to determine the general anatomy of the esophagus and identify other pathologies of this organ (perforation, esophageal diverticulum).

In addition to the above studies, the following are also carried out:

- Endoscopic pH-metry (to confirm the diagnosis of GERD);

- Esophagomanometry (in case of suspected violations of the motor function of the esophagus);

- CT scan of the chest and abdomen (when the stricture is determined to be malignant or the narrowing of the esophagus is believed to be caused by external pathology);

- Endoscopic ultrasonography (to assess the nature of the stricture, stage and severity of the malignant process).

Treatment tactics differ depending on the nature of the esophageal stricture.

Treatment of benign stricture consists of restoring the lumen of the esophagus in combination with conservative therapy to eliminate the underlying disease. The basis of the latter is a course of proton pump inhibitors followed by endoscopic monitoring and correction of therapy by a gastroenterologist.

Restoration of esophageal patency can be achieved using balloon dilatation in combination with local steroid injections around the stricture.

Also, for benign strictures, it is possible to perform a surgical procedure:

- antireflux operations: fundoplications in various modifications in combination with crurorrhaphy. They are performed to eliminate hiatal hernias, which contribute to the development of GERD and reflux esophagitis.

- endoscopic resection (in cases of repeated stricture of the esophagus and ineffectiveness of balloon dilatation);

- esophagojejunostomy (in cases of ulcerative stricture and lack of effect from conservative therapy).

In addition to the listed operations, segmental resection of the distal esophagus and esophagogastrostomy are indicated in the literature, however, such operations should be used with caution, since they cause a severe form of GERD, as a result of which the patient continues to have problems with ulcerative lesions of the esophagus.

Treatment of malignant esophageal stricture depends on the location and operability of the formation. In this situation, dilatation plays a temporary role and is therefore considered as a preparatory procedure for stent installation or resection.

In the case of an inoperable tumor or when the patient needs to complete neoadjuvant therapy before resection of the tumor, stenting may be performed.

In the case of operable cancer of the distal esophagus, surgical treatment is indicated according to all the rules of oncological surgery. We will tell you more about this in the article on esophageal cancer.

Sources:

- Pregun I, Hritz I, Tulassay Z, et al. Peptic esophageal stricture: medical treatment. Dig Dis 2009;27:31–7.

- Pace F, Antinori S, Repici A. What is new in esophageal injury (infection, drug-induced, caustic, stricture, perforation)? Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2009;25:372–9.

- Guda NM, Vakil N. Proton pump inhibitors and the time trends for esophageal dilation. Am J Gastroenterol 2004;99:797–800.

- Marks RD, Richter JE, Rizzo J, et al. Omeprazole versus H2-receptor antagonists in treating patients with peptic stricture and esophagitis. Gastroenterology 1994; 106:907–15.

- Dakkak M, Hoare RC, Maslin SC, et al. Oesophagitis is as important as oesophageal stricture diameter in determining dysphagia. Gut 1993;34:152–5.

- Patterson DJ, Graham DY, Smith JL, et al. Natural history of benign esophageal stricture treated by dilatation. Gastroenterology 1983;85:346–50.

- Smith CD. Antireflux surgery. Surg Clin North Am 2008;88:943–58.

Surgery

Indications for surgical treatment are localized (early) forms of esophageal cancer without damage to surrounding structures: I-IIA (T1-3N0M0). Surgery is also indicated for high-grade dysplasia in Barrett's esophagus, which is considered cr in situ.

Surgical treatment includes:

- Endoscopic mucosectomy (removal of the esophageal mucosa) when malignant cells are located within the mucosa. Endoscopic resection is the treatment of choice for carcinoma in situ and severe dysplasia. In addition, the method is successfully used for tumors of the esophagus that do not extend beyond the mucosa, in patients with a significant risk of surgical complications. At the same time, the 5-year survival rate reaches 85-100%.

- Subtotal resection of the esophagus with simultaneous plasty of a gastric tube or segment of the colon.

The main type of operation is transthoracic subtotal resection of the esophagus with simultaneous intrapleural plastic surgery of the stomach stalk or a segment of the colon with bilateral two-zone mediastinal lymph node dissection from a combined laparotomy and right-sided thoracotomy approach (Lewis type).

In some clinics, transhiatal resections of the esophagus are performed as an alternative, which cannot be considered radical. They should not be used in patients with thoracic esophageal cancer, since adequate mediastinal lymph node dissection above the tracheal bifurcation is not possible from the laparotomy approach.

Another way to reduce the number of surgical complications is minimally invasive (thoraco-laparoscopic) or hybrid (thoracotomy + laparoscopic or thoracoscopy + laparotomy) esophagectomy or robot-assisted esophagectomy.

Read more about the operation at the link . We warn you that the materials contain naturalistic images.

Anatomy of the Human Esophagus - information:

Esophagus, the esophagus, is a narrow and long active tube inserted between the pharynx and the stomach and helps move food into the stomach. It begins at the level of the VI cervical vertebra, which corresponds to the lower edge of the cricoid cartilage of the larynx, and ends at the level of the XI thoracic vertebra.

Since the esophagus, starting in the neck, passes further into the chest cavity and, perforating the diaphragm, enters the abdominal cavity, its parts are distinguished: partes cervicalis, thoracica et abdominalis. The length of the esophagus is 23-25 cm. The total length of the path from the front teeth, including the oral cavity, pharynx and esophagus, is 40-42 cm (at this distance from the teeth, adding 3.5 cm, a gastric rubber probe must be advanced into the esophagus to take gastric juice for examination).

Topography of the esophagus. The cervical part of the esophagus is projected from the VI cervical to the II thoracic vertebra. The trachea lies in front of it, the recurrent nerves and common carotid arteries pass to the side.

The syntopy of the thoracic part of the esophagus is different at different levels: the upper third of the thoracic esophagus lies behind and to the left of the trachea, in front of it are the left recurrent nerve and the left a. carotis communis, behind - the spinal column, on the right - the mediastinal pleura. In the middle third, the aortic arch is adjacent to the esophagus in front and to the left at the level of the IV thoracic vertebra, slightly lower (V thoracic vertebra) - the bifurcation of the trachea and the left bronchus; behind the esophagus lies the thoracic duct; To the left and somewhat posteriorly the descending part of the aorta adjoins the esophagus, to the right is the right vagus nerve, to the right and posteriorly is the v. azygos. In the lower third of the thoracic esophagus, behind and to the right of it lies the aorta, in front - the pericardium and the left vagus nerve, on the right - the right vagus nerve, which is shifted below to the posterior surface; v lies somewhat posteriorly. azygos; on the left - the left mediastinal pleura.

The abdominal part of the esophagus is covered with peritoneum in front and on the sides; the left lobe of the liver is adjacent to it in front and to the right, the upper pole of the spleen is to the left, and a group of lymph nodes is located at the junction of the esophagus and the stomach.

Structure. On a cross-section, the lumen of the esophagus appears as a transverse slit in the cervical part (due to pressure from the trachea), while in the thoracic part the lumen has a round or stellate shape.

The wall of the esophagus consists of the following layers: the innermost - the mucous membrane, tunica mucosa, the middle - tunica muscularis and the outer - connective tissue in nature - tunica adventitia.

Tunica mucosa contains mucous glands that facilitate the sliding of food during swallowing with their secretions. In addition to the mucous glands, small glands similar in structure to the cardiac glands of the stomach are also found in the lower and, less commonly, upper sections of the esophagus. When not stretched, the mucous membrane gathers into longitudinal folds. Longitudinal folding is a functional adaptation of the esophagus, facilitating the movement of fluids along the esophagus along the grooves between the folds and stretching the esophagus during the passage of dense lumps of food. This is facilitated by the loose tela submucosa, thanks to which the mucous membrane acquires greater mobility, and its folds easily appear and then smooth out. The layer of unstriated fibers of the mucous membrane itself, lamina muscularis mucosae, also participates in the formation of these folds. The submucosa contains lymphatic follicles.

Tunica muscularis , corresponding to the tubular shape of the esophagus, which, when performing its function of carrying food, must expand and contract, is located in two layers - the outer, longitudinal (dilating esophagus), and the internal, circular (constricting). In the upper third of the esophagus, both layers are composed of striated fibers; below they are gradually replaced by non-striated myocytes, so that the muscle layers of the lower half of the esophagus consist almost exclusively of involuntary muscles.

Tunica adventitia , surrounding the outside of the esophagus, consists of loose connective tissue through which the esophagus is connected to the surrounding organs. The looseness of this membrane allows the esophagus to change the size of its transverse diameter as food passes through.

Pars abdominalis of the esophagus is covered with peritoneum.

X-ray examination of the digestive tube is carried out using the method of creating artificial contrasts, since without the use of contrast media it is not visible. For this, the subject is given a “contrast food” - a suspension of a substance with a high atomic mass, preferably insoluble barium sulfate. This contrast food blocks x-rays and produces a shadow on the film or screen that corresponds to the cavity of the organ filled with it. By observing the movement of such contrasting food masses using fluoroscopy or radiography, it is possible to study the x-ray picture of the entire digestive canal. When the stomach and intestines are completely or, as they say, “tightly” filled with a contrasting mass, the X-ray picture of these organs has the character of a silhouette or, as it were, a cast of them; with a small filling, the contrast mass is distributed between the folds of the mucous membrane and gives an image of its relief.

X-ray anatomy of the esophagus. The esophagus is examined in oblique positions - in the right nipple or left scapular. During an X-ray examination, the esophagus containing a contrasting mass has the appearance of an intense longitudinal shadow, clearly visible against the light background of the pulmonary field located between the heart and the spinal column. This shadow is like a silhouette of the esophagus. If the bulk of the contrast food passes into the stomach, and swallowed air remains in the esophagus, then in these cases one can see the contours of the walls of the esophagus, clearing at the site of its cavity and the relief of the longitudinal folds of the mucous membrane. Based on X-ray data, it can be noted that the esophagus of a living person differs from the esophagus of a corpse in a number of features due to the presence of intravital muscle tone in a living person. This primarily concerns the position of the esophagus. On the corpse it forms bends: in the cervical part the esophagus first runs along the midline, then slightly deviates from it to the left; at the level of the V thoracic vertebra it returns to the midline, and below it again deviates to the left and forward to the hiatus esophageus of the diaphragm. In a living person, the bends of the esophagus in the cervical and thoracic regions are less pronounced.

The lumen of the esophagus has a number of narrowings and expansions that are important in the diagnosis of pathological processes:

- pharyngeal (at the beginning of the esophagus),

- bronchial (at the level of tracheal bifurcation)

- diaphragmatic (when the esophagus passes through the diaphragm).

These are anatomical narrowings that remain on the corpse. But there are two more narrowings - aortic (at the beginning of the aorta) and cardiac (at the transition of the esophagus to the stomach), which are expressed only in a living person. Above and below the diaphragmatic constriction there are two expansions. The inferior expansion can be considered as a kind of vestibule of the stomach. Fluoroscopy of the esophagus of a living person and serial photographs taken at intervals of 0.5-1 s allow one to study the act of swallowing and peristalsis of the esophagus.

Endoscopy of the esophagus. During esophagoscopy (i.e., when examining the esophagus of a sick person using a special device - an esophagoscope), the mucous membrane is smooth, velvety, and moist. Longitudinal folds are soft and plastic. Along them there are longitudinal vessels with branches.

The esophagus is fed from several sources, and the arteries feeding it form abundant anastomoses among themselves. Ah. esophageae to pars cervicalis of the esophagus come from a. thyroidea inferior. Pars thoracica receives several branches directly from the aorta thoracica, pars abdominalis feeds from the aa. phrenicae inferiores et gastrica sinistra. Venous outflow from the cervical part of the esophagus occurs in v. brachiocephalica, from the thoracic region - in vv. azygos et hemiazygos, from the abdominal - into the tributaries of the portal vein. From the cervical and upper third of the thoracic esophagus, lymphatic vessels go to the deep cervical nodes, pretracheal and paratracheal, tracheobronchial and posterior mediastinal nodes. From the middle third of the thoracic region, the ascending vessels reach the named nodes of the chest and neck, and the descending vessels (through the hiatus esophageus) - the nodes of the abdominal cavity: gastric, pyloric and pancreaticoduodenal. Vessels coming from the rest of the esophagus (supradiaphragmatic and abdominal sections) flow into these nodes.

The esophagus is innervated from n. vagus et tr. sympathicus. Along the branches of tr. sympathicus conveys the feeling of pain; sympathetic innervation reduces esophageal peristalsis. Parasympathetic innervation enhances peristalsis and gland secretion.

Combined treatment. Chemotherapy and radiation therapy

The results of surgical treatment alone for more common stages remain unsatisfactory; only about 20% of patients survive 5 years. In order to improve results, various combinations of drug and radiation therapy are used (preoperative chemotherapy, preoperative chemoradiotherapy, independent chemoradiotherapy).

Chemotherapy

A. Preoperative (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy;

B. Postoperative (adjuvant) chemotherapy.

For adenocarcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus or esophagogastric junction, perioperative chemotherapy is most justified, when 2-3 courses of chemotherapy are prescribed before surgery, and 3-4 courses after it . If overexpression of HER 2neu is detected, trastuzumab in standard doses is included in the treatment regimen.

For adenocarcinoma of the lower thoracic esophagus or esophagogastric junction, postoperative chemotherapy is indicated if it was also carried out preoperatively. Adjuvant chemotherapy alone for esophageal adenocarcinoma is not currently recommended.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy alone (without chemotherapy) before or after surgical treatment is not indicated due to its low effectiveness.

A. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy

Before chemoradiotherapy, it is possible to conduct 1-2 courses of chemotherapy, which makes it possible to reduce dysphagia in most patients and plan radiation therapy in advance.

External beam radiation therapy using linear accelerators is highly desirable. A single focal dose is 1.8-2 Gy, the total dose is up to 44-45 Gy. During radiation therapy, chemotherapy based on cisplatin or carboplatin is given. In the presence of severe dysphagia, endoscopic electrorecanalization/argon plasma recanalization of the esophagus or puncture gastrostomy is performed before irradiation.

Surgery usually occurs 6-8 weeks after completion of chemoradiotherapy.

The optimal regimen of chemoradiotherapy appears to be weekly administration of paclitaxel and carboplatin followed by 5 weeks of radiation therapy. This preoperative regimen (compared to surgery alone) makes it possible to achieve complete pathomorphosis in 23% of patients with adenocarcinoma. Postoperative mortality is 4%, and 5-year survival is improved from 34% to 47%.

B. Postoperative chemoradiotherapy

Postoperative chemoradiotherapy can be performed in patients in satisfactory condition in the presence of micro or macroscopic residual tumor (after R1 or R2 resection). Regimes and doses are similar to preoperative ones.

Achalasia cardia

The main threat of achalasia is a critical increase in the size of the esophagus, leading to a complete loss of swallowing function. In this case, the patient requires a complex and traumatic operation - extirpation (removal) of the esophagus and the creation of a new esophagus from part of the stomach.

- What is achalasia cardia

The lower esophageal sphincter (cardiac sphincter) is located at the junction of the esophagus and the stomach. During the normal act of swallowing, food moves down the esophagus and approaches the area of the lower esophageal sphincter, its muscle fibers reflexively relax, and the food enters the stomach. With achalasia, the circular muscle fibers that make up the lower esophageal sphincter, which passes food into the stomach, do not relax or relax with difficulty. Food is not able to flow freely into the stomach. It accumulates in the esophagus, causing its tractional expansion.

- Causes

The main cause of achalasia is a psychoemotional factor. The emotional environment in large cities is unfavorable, patients experience stress at work and at home, so achalasia is a fairly common disease nowadays. If a patient comes for a consultation and says: “Doctor, I was very nervous, and after that I began to ache behind the sternum. I have trouble swallowing food, there’s a lump in my throat…” – first of all, the doctor suggests achalasia. If something similar happens to you, do not delay visiting a doctor. The longer a patient has achalasia, the more pronounced the clinical manifestations of achalasia become.

- Symptoms and complications

The main symptom of achalasia is dysphagia - difficulty swallowing. In the initial stages of achalasia, liquids are less readily swallowed than solids. If solid food enters the esophagus, esophageal peristalsis pushes it into the stomach through the tense cardiac sphincter. The peristalsis of the esophagus has practically no effect on the liquid. Liquid is retained in the esophagus and is difficult to swallow. Another important symptom of achalasia is pain at the end of the act of swallowing. Food passes through the esophagus to the lower sphincter. The peristaltic movements of the esophagus try to push it through the compressed sphincter, resulting in quite intense pain.

In addition to dysphagia and pain, there are extraesophageal manifestations of achalasia - aspiration bronchitis and aspiration pneumonia. If food does not pass into the stomach, it remains in the esophagus. The patient takes a horizontal position and falls asleep - the contents of the esophagus flow into the oral cavity and penetrate into the bronchi and lungs during inhalation (aspiration). As a result, aspiration bronchitis and pneumonia develop. In addition, when aspirating food there is a risk of reflex respiratory arrest.

Increased pressure in the esophagus can lead to the development of diverticula, which increase in size over time. A separate article is devoted to diverticula of the esophagus. But more often, a patient with achalasia experiences dilation of the lumen of the esophagus. And the longer achalasia exists, the larger the diameter of its esophagus. At the late stage of achalasia, the dilation of the esophagus becomes irreversible.

Achalasia cardia

Image source: Timonina/Shutterstock

- Stages of achalasia

To diagnose and determine the stage of achalasia, the Ilyinsky Hospital uses X-ray examination with water-soluble contrast agent (in some cases, CT scan with contrast) and endoscopic examination. There are 4 stages of achalasia. The greater the dilation of the esophagus, the higher the stage of achalasia. At stages 1 and 2, the lumen of the esophagus is increased. At stages 3 and 4, the esophagus changes its anatomical configuration, tending to an S-shape. At stage 4, the size of the esophagus may exceed the size of the stomach.

- Low-traumatic endoscopic surgery

For patients with stages 1, 2 and 3 of achalasia, surgeons at the Ilyinsk Hospital perform a minimally invasive endoscopic operation - peroral esophageal myotomy - POEM (peroral esophageal myotomy). The operation is performed without external incisions. A special thin endoscope is inserted into the esophagus, and microminiature surgical instruments are passed through the instrument channel of the endoscope. Having retreated about 10 cm from the lower esophageal sphincter, the surgeon peels off the mucous membrane of the esophagus from the muscle layer, creating a “tunnel”. The endoscope is inserted into the submucosal layer and gradually moves towards the sphincter. The task of the endoscopic surgeon is to cut the muscle fibers of the esophagus in an area of about 7 cm from the sphincter, reach the circular muscle fibers of the sphincter and completely cross them. After dissecting the muscle fibers, the endoscope is removed, the access site is closed using special clips, and the operation is completed. Peroral esophagocardiomyotomy is possible at stages 1, 2 and 3 of achalasia. However, there is scientific evidence suggesting that even in stage 4 this operation has a good effect.

- Laparoscopic surgery

Stage 3 achalasia does not always allow endoscopic surgery. In this case, surgeons at the Ilyinsk Hospital perform laparoscopic esophagocardiomyotomy, the so-called Geller operation. Five small incisions are made on the anterior abdominal wall, through which a laparoscope and surgical manipulators are passed into the abdominal cavity. The surgeon moves to the area of the lower alimentary sphincter and very precisely crosses its circular muscle fibers. Then a Dor fundoplication is performed - part of the stomach is wrapped around the esophagogastric junction and takes on the function of a sphincter, which avoids the development of gastroesophageal reflux (reflux of acid from the stomach into the esophagus).

- Extirpation of the esophagus

In patients with stage 4 achalasia, the esophagus is S-shaped and maximally dilated, its lumen can exceed 10 cm. The peristalsis of such an esophagus is either ineffective or absent at all - the esophagus does not perform its function. Such patients can only be helped by esophageal extirpation - an operation to completely remove the esophagus. The non-functioning esophagus is almost completely removed. A portion of the stomach wall is removed and a new esophagus is formed from it. The operation lasts about 10 hours.

- Accelerated rehabilitation

The Ilyinskaya Hospital has implemented the concept of accelerated rehabilitation surgery (fast track surgery). This ideology is based on the results of many years of international clinical research, recognized and implemented in all developed countries. It includes simplified preparation for surgery, performing the operation on the day of hospitalization, minimizing surgical access (laparoscopy and endoscopy), maximum efforts to preserve the affected organ (instead of removing the organ), early awakening of the patient after anesthesia, early mobilization of the patient (you can get up on your feet) soon after the operation), early alimentation (you can start eating and drinking soon after the operation). This set of measures is aimed at the fastest possible rehabilitation of the patient after surgery and restoration of his quality of life.

- Pain Management Service

Patients of the Ilyinskaya Hospital do not experience pain - this is monitored by a special general hospital service - the Pain Treatment Service. Our specialists have a full range of analgesics, including powerful opioid drugs, and high-tech instrumental techniques that have proven themselves in the West, but are rarely used in our country.

- Hospital at home

For the most severe patients treated in our hospital, we are ready to organize a “hospital at home”. Even after the most complex and difficult surgical operation, the patient can be transferred home quite quickly. The home environment and closeness of family contribute to a speedy recovery. We provide constant monitoring of the patient using a specially selected set of monitors, monitor drug therapy and organize regular classes with a rehabilitation instructor. At home, intravenous infusions, mask ventilation and other procedures and manipulations can be successfully performed.

Self-administered chemoradiotherapy

An alternative to surgical treatment of resectable locally advanced forms of esophageal cancer is chemoradiotherapy, which achieves a comparable 5-year overall survival rate of 20-27%. In a head-to-head study comparing cisplatin-based chemoradiotherapy with 5-fluorouracil infusion versus surgery alone, there was no significant difference in long-term outcomes, and toxicity and mortality were significantly lower with conservative treatment.

It is highly desirable to carry out conformal 3D CRT external beam radiation therapy on linear accelerators with an energy of 6-18 Mev, as well as on proton complexes operating with an energy of 70-250 Mev. A single focal dose is 1.8-2 Gy, the total dose is up to 50-55 Gy. Increasing SOD does not lead to improved results, only increasing mortality.

During radiation therapy, chemotherapy is administered , often based on cisplatin and infusions of 5-fluorouracil. In the presence of severe dysphagia, endoscopic electrorecanalization of the esophagus or puncture microgastrostomy is performed before irradiation. Chemoradiation therapy is often complicated by the development of radiation esophagitis and an increase in the severity of dysphagia, which aggravates the patient’s nutritional deficiency and worsens the tolerability of treatment. In such situations, a partial or complete transition to parenteral nutrition and placement of a temporary puncture microgastrostomy is possible.

The choice between independent chemoradiotherapy or surgical treatment (with or without preoperative chemoradiotherapy) depends on the location of the primary tumor, the patient's functional status, and the experience of the surgeon. Thus, in intact patients with a tumor localized in the middle or lower third of the esophagus, it is preferable to include surgery in the treatment plan.

If the tumor remains viable after chemoradiotherapy or local relapse, a so-called “salvage esophagectomy” can be performed.

Palliative treatment of inoperable patients

The main goals of treating patients with metastatic esophageal cancer are eliminating painful symptoms and increasing life expectancy.

Assessing the effectiveness of various chemotherapy regimens for esophageal cancer is hampered by the lack of randomized trials. For this reason, it is even difficult to assess the benefit that chemotherapy provides compared to maintenance therapy.

Chemotherapy is recommended for patients in satisfactory condition and in the absence of severe (III-IV) dysphagia, which complicates the patient’s adequate nutrition. In the latter case, the first stage shows restoration of esophageal patency (stenting, recanalization). In case of dysphagia of I-II degrees, the beginning of chemotherapy makes it possible to achieve a decrease in the degree of its severity in a number of patients by the end of the first course.

Esophageal stenting for cancer

The most active drugs for both histological variants are cisplatin, fluoropyrimidines, and taxanes. In addition, oxaliplatin, irinotecan, and trastuzumab (with overexpression of HER-2 neu) are also effective for adenocarcinomas.

After treatment

Inspection

Patients after radical treatment (surgery or chemoradiotherapy) should be examined every 3-6 months. in the first 2 years, then every 6-12 months. in the next 3-5 years, then annually.

Analyzes

Blood tests and instrumental examinations are prescribed only for clinical indications (the appearance of complaints or symptoms of progression).

EGDS

Patients with early cancer who have undergone endoscopic mucosal resection should undergo EGD every 3 months. in the first year, every 6 months. in the second and third years, then annually.

Forecast

The prognosis for esophageal adenocarcinoma is determined by the stage of the disease. Unfortunately, the structural features of the esophagus, the high risk of metastasis, and the lack of a specific clinical picture in the early stages of the disease lead to the fact that 2/3 of patients have stage 3 or 4 at the time of diagnosis. This is either a locally advanced inoperable process or distant metastases in the lungs, liver, and bones. In this case, the 12-month survival rate is only 38%.

With localized stages, 5-year survival rate can reach 47%, with damage to regional lymph nodes - 25%, in the presence of distant sites of stasis does not exceed 5%.

Surgical treatment in the department of thoracoabdominal surgery and oncology of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery

Treatment in the department is carried out under the programs of compulsory medical insurance, voluntary medical insurance, VMP, as well as on a commercial basis. Read how to get treatment at the Department of Thoracoabdominal Surgery and Oncology of the Russian Scientific Center for Surgery.

To schedule a consultation, call:

+7 (499) 248 13 91 +7 (903) 728 24 52 +7 (499) 248 15 55

Submit a request for a consultation by filling out the form on our website and attaching the necessary documents.