Short bowel syndrome (SBS) refers to a disorder of absorption processes in the intestine. It occurs as a result of previous surgery. The problem of short bowel may also be congenital. If the size of the intestine is insufficient, difficulties arise with digesting food, and other unpleasant symptoms occur. The clinical picture is caused by an acute lack of significant absorptive surface of the intestine.

The degree of prevalence of intestinal pathology that occurs during resection depends on the criteria of the syndrome. According to statistics, SBS is diagnosed quite rarely - in 1.4 cases per million. The manifestation of clinical signs is mainly observed in people with a bowel size of less than 1 m.

Causes of short bowel syndrome

In rare cases, short bowel syndrome is congenital and is diagnosed in children at an early age. Often, the short size of the intestine, which subsequently negatively affects the patient’s well-being, is associated with massive resection for malformations of the digestive system organ. Other causes of intestinal pathology include:

- necrotizing enterocolitis;

- gastroschisis with volvulus;

- intestinal atresia of prolonged or multiple type, characterized by incomplete formation of part of the small intestine;

- adhesive obstruction;

- thrombosis of intestinal blood vessels;

- malignant or benign tumors of the intestine that were removed surgically;

- wounds and mechanical damage to the intestines.

Depending on the type of resection, short bowel syndrome can be of varying degrees, which affects the intensity and variety of clinical symptoms. The most severe case is complete surgical removal of the small and large intestine. It is also possible that the organ is partially removed, preserving the ileocecal valve located between the small and large intestines.

Physiology of the small intestine

The internal organ is part of the digestive system and includes three segments - duodenum, jejunum and ileum. Main functions of the small intestine:

- absorption of nutritional components;

- ensuring peristalsis;

- formation of digestive juices.

Nutrients enter the initial parts of the intestine, where water and beneficial microelements are absorbed. The distal parts of the intestine are responsible for the absorption of bile salts and vitamin B12.

The length of the small intestine varies depending on age. So, in newborns it reaches 2.5 m, and in adults - from 3.5 to 6 m. Due to the presence of many folds in the intestine, the organ has a large absorption surface. The ileocecal valve, located at the junction of the large and small intestines, serves as a kind of barrier, preventing the passage of microorganisms from one organ to another.

The clinical picture of short bowel syndrome is associated specifically with dysfunction of the small intestine. The intensity of symptoms depends on the location of the intestinal damage and the length of the defect. During resection, the organ not only becomes short, but also the absorption surface area is significantly reduced, which provokes an acceleration of the movement of the contents and a reduction in the time of its contact with the intestinal mucosa. These factors contribute to the manifestation of symptoms of short bowel syndrome.

Principles of management of patients with short bowel syndrome

Baranskaya E.K., Shulpekova Yu.O.

Short bowel syndrome is a complex of symptoms that develops after extensive resections of the small intestine. Similar operations are performed for Crohn's disease, intestinal ischemia, radiation enteritis, volvulus of the small intestine, desmoid tumors, trauma, etc. The prevalence of short bowel syndrome is difficult to assess, since its manifestations vary significantly in severity and not all cases are recorded by medical statistics. According to some estimates, in European countries, the prevalence of severe forms is 1.8-2 per 1 million population [5].

The length of the small intestine varies from 275 to 850 cm; in women it is shorter than in men. Under physiological conditions in healthy individuals, the total area of the actively functioning absorption and secreting surface of the small intestinal mucosa is colossal and comparable to the area of a tennis court (500 m2), and the area of the colon mucosa approximately corresponds to the surface area of a table tennis table (4 m2). A significant decrease in intestinal function due to resection leads to the development of specific short bowel syndrome and intestinal failure.

Short bowel syndrome is particularly severe in patients who have undergone resection with less than 2 m of small bowel remaining.

Based on the extent of resection, three main types of clinical and anatomical changes can be distinguished [8,13,16].

- Resection of the small intestine while preserving at least part of the ileum, ileocecal valve and colon. Such patients are less susceptible to severe digestive disorders and rarely require long-term artificial nutrition.

- Resection of the small intestine with jejuno-colic anastomosis. Patients with jejuno-colic anastomosis feel satisfactory for the first time after surgery, although signs of steatorrhea are noted. In subsequent months, trophological deficiency gradually manifests itself. However, over time, functional adaptation is possible with a decrease in the need for nutrients. Eating amounts of food that are normal for healthy people is accompanied by the appearance of diarrhea. If less than 50 cm of small bowel is retained, maintenance parenteral nutrition may be necessary.

- Resection of the small intestine and colectomy with the creation of a jejunostomy. This option is characterized by diarrhea with the development of dehydration, electrolyte disorders (hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia, hyponatremia) and trophological insufficiency in the near future after surgery. Diarrhea worsens after eating or drinking. Over time, no significant physiological adaptation of the intestine is observed. With jejunostomy, it is often necessary to constantly take isotonic solutions of sodium and glucose orally, take antidiarrheal drugs, and in some cases, parenteral nutrition and the administration of plasma substitutes.

The concept of intestinal failure. Intestinal failure syndrome (IF) involves disturbances in digestion and absorption, leading to the need for additional special nutrition and/or fluid and electrolyte support [11]. In the absence of adequate treatment, trophological insufficiency and/or dehydration develop in CI. The severity of CN can be most accurately determined by methods of calculating the energy balance that are inaccessible in practice. Based on treatment needs, CI is classified as mild, moderate, or severe.

- Mild: the need to select a special diet with a high content of nutrients and/or oral intake of glucose-saline solutions.

- Moderate severity: the need to prescribe special enteral nutrition and oral administration of glucose-saline solutions.

- Severe: the need for parenteral nutrition and administration of glucose-saline solutions.

As a rule, signs of CI develop when the length of the preserved segment of the small intestine is less than 2 m. Resection with preservation of less than 40-50 cm is considered as the most unfavorable prognostically for the development of the most severe forms of CI.

CI can be acute or chronic, which is determined by the reasons for its development. Acute CI, as a rule, is a manifestation of infectious or radiation enteritis, intestinal ileus, and intestinal fistulas. Chronic CI develops as a result of surgical interventions (resection of the small intestine with the formation of anastomoses and stomas), and is also observed in Crohn's disease with damage to the small intestine, radiation enteritis, and gross motility disorders.

Pathophysiological changes after small bowel resection

Acceleration of passage through the intestines. During resection of the ileum and colon, due to disruption of the natural obturator mechanism, the rate of gastric emptying and passage through the small intestine increases significantly. This is mediated by low levels of production of YY-peptide and glucagon-like peptide-2, which are normally secreted by the cells of the ileal and colon mucosa and play an important role in the regulation of appetite and motility.

Loss of sodium and water. Under physiological conditions, passive secretion in the jejunum helps to achieve isotonic equilibrium between the intestinal contents and plasma. Most of the fluid must be reabsorbed in the jejunum, so significant losses of water and electrolytes may occur during resection and jejunostomy. If the length of the jejunum proximal to the stoma is less than 1 m, fluid loss through the stoma may exceed the amount ingested. If the patient ingests a hypotonic solution (with a sodium content of less than 90 mmol/l), additional loss of sodium occurs due to its diffusion from the plasma into the intestinal lumen along a concentration gradient.

Hypersecretion of gastric juice. In the first 2 weeks. after resection of the small intestine, hypersecretion of gastric juice is observed [20].

Impaired absorption and magnesium-calcium metabolism. After resection of more than 60-100 cm of the terminal portion of the ileum, malabsorption of fats, vitamin B12 and bile acids develops, which is not compensated by an increase in their synthesis in the liver. Unabsorbed bile acids enter the colon, where they stimulate the secretion of water and electrolytes. Unabsorbed fatty acids bind magnesium ions. At the same time, due to secondary hyperaldosteronism, the loss of magnesium in the urine increases. Hypomagnesemia is accompanied by a decrease in the activity of parathyroid hormone, inhibition of the production of D-1,25-dioxycholecalciferol, and calcium uptake in the renal tubules and intestines.

Adaptive processes after resection. With short bowel syndrome, compensatory hyperphagia often develops. In the intestine, there is an increase in the area of the absorbent surface - structural adaptation - as well as a slowdown in transit - functional adaptation.

In patients with jejuno-colic anastomosis, gastric emptying and passage through the small intestine may slow down over time due to increased activity of YY-peptide and glucagon-like peptide - 2 in the blood; the intensity of absorption of nutrients, water, sodium and calcium gradually increases.

Patients with jejunostomy do not develop any significant adaptation [7].

Clinical assessment in short bowel syndrome consists, first of all, in characterizing the trophological status and water-electrolyte metabolism, including analysis of sodium, magnesium and calcium content.

Trophological insufficiency is manifested in a decrease in body weight by more than 10%, body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m2, shoulder muscle circumference <19 cm in women and <22 cm in men.

With jejunostomy, assessing the degree of hydration, sodium and magnesium levels in the blood, monitoring body weight and the volume of discharge through the jejunostomy is extremely important. Signs of dehydration and sodium deficiency are usually thirst and arterial hypotension, up to the development of prerenal anuria. Severe sodium deficiency is characterized by a decrease in its concentration in urine <10 mmol/l.

For a long-term prognosis and choice of treatment tactics, it is necessary to clarify the length of the remaining section of the intestine from the duodenojejunal ligament, which is possible during surgery or with contrast radiography.

General principles of patient management. The goal of treatment for patients with short bowel syndrome is to meet the body's water, electrolyte, and nutrient needs, preferring oral/enteral nutrition over parenteral nutrition when possible. Management of patients by a team of specialists can prevent the rapid development of dehydration, reduce the risk of complications associated with CI and artificial nutrition (in particular, liver dysfunction, septic complications), and improve the quality of life of patients.

In the most severe forms (jejunostomy with a portion of the remaining part of the jejunum less than 50 cm), it is vital to provide complete parenteral nutrition and rehydration. With a relatively long preserved segment of the small intestine and preservation of the passage through the large intestine (small-colon anastomosis), the diet and fluid intake approaches the natural one.

Features of management of patients with jejuno-colic anastomosis

Nutritional features. In the next 6 months. after surgery, given the tendency to gastric hypersecretion, antisecretory agents should be prescribed. When eating food by mouth, it should be taken into account that 50% of the energy or more may not be absorbed due to malabsorption, therefore the energy value of food should be increased; Feeding at night is indicated. If the effect is insufficient, parenteral nutrition should be added for several weeks or months [3].

The entry of long-chain fatty acids into the colon provokes an acceleration of transit, a decrease in water absorption, and thereby aggravates diarrhea. Fatty acids inhibit the activity of bacteria that ferment carbohydrates and bind calcium, zinc and magnesium. The latter contributes to an increase in diarrhea, absorption of oxalates and an increased risk of urolithiasis. When selecting a diet, preference should be given to the inclusion of medium- and short-chain triglycerides that can be absorbed in both the small and large intestines, for example, products based on coconut and palm oils, nutritional mixtures “Peptamen”, “Clinutren” [22]. Carbohydrates in the diet of such patients should be represented mainly by polysaccharides (in jelly, porridge and soups made from buckwheat, oatmeal, pearl barley, millet, corn grits, mashed potatoes, unsweetened and low-fat custard cream). Taking large amounts of mono- and oligosaccharides carries a risk of lactic acidosis as a result of overproduction of lactic acid by small intestinal lactobacilli and colon microflora at fecal pH above 6.5 [6].

When the colon is preserved, significant disturbances in water and electrolyte balance are rarely observed. In case of a decrease in sodium content during the day, it is recommended to take an isotonic glucose-saline solution orally in an amount determined by the degree of dehydration (the usual physiological need is about 30 ml/kg of body weight).

In most cases, maintenance treatment with vitamin B12 and selenium preparations is necessary. In some patients, there is a need to compensate for the deficiency of zinc, essential fatty acids, and fat-soluble vitamins A, E, D, K.

Treatment of diarrhea. Diarrhea in short bowel syndrome is predominantly osmotic and partly hypersecretory and hyperkinetic in nature, caused by impaired secretion of gastrointestinal hormones. As the amount of food consumed by mouth is reduced, diarrhea improves, and in some cases temporary parenteral nutrition may be required. The principles of drug treatment of diarrhea are similar to those for jejunostomy: prescribing loperamide in a dose of 2-8 mg half an hour before meals, codeine phosphate in a dose of 30-60 mg before meals. If 100 cm or more of the terminal ileum is resected and bile acid malabsorption contributes to the development of diarrhea, it is advisable to prescribe cholestyramine.

In patients with small-colic anastomosis, episodes of confusion have been recorded, the causes of which may be a decrease in magnesium content (<0.2 mmol/l), thiamine deficiency (Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome, the main manifestations of which are severe memory impairment, coordination disorders in combination with polyneuropathy), lactic acidosis and hyperammonemia due to citrulline deficiency. Treatment consists of correcting magnesium deficiency, prescribing thiamine, an intermediate product of the urea synthesis cycle - arginine, and broad-spectrum antibiotics; in some cases, temporary parenteral nutrition is indicated [21].

Reducing the risk of cholelithiasis and urolithiasis. The incidence of calcium-bilirubin gallstones after intestinal surgery reaches 45%. The probable cause of cholelithiasis in these patients is a decrease in the activity (absence) of enterohepatic circulation of bilirubin and stasis of bile in the gallbladder and bile ducts. Prevention preferably includes enteral nutrition, administration of cholecystokinin, administration of ursodeoxycholic acid, and suppression of overgrowth of intestinal bacteria. Some surgeons prefer to perform prophylactic cholecystectomy when undergoing large-scale resection of the small intestine.

The risk of formation of oxalate urinary stones and nephrocalcinosis after small bowel resection reaches 25%. To prevent urolithiasis, one should prevent the development of dehydration, exclude foods rich in oxalates, and enrich the diet with medium-chain triglycerides and calcium (diet type No. 5).

Features of managing patients with jejunostomy. Unlike patients with small-colic anastomosis, jejunostomy patients experience significant loss of fluid and electrolytes, but there are no problems associated with severe bacterial fermentation in the colon.

When managing patients with a jejunostomy, it is necessary to monitor the volume of intestinal contents discharged through the stoma per day. A large volume of discharge may indicate the presence of unrecognized infectious complications, partial/transient intestinal obstruction, active enteritis (for example, clostridial).

Correction of water and electrolyte deficiency. Losses through the stoma increase after fluid and food intake, and each liter of discharge contains ≈100 mmol of sodium. If the length of the remaining jejunum is more than 50 cm, potassium loss is relatively small (≈15 mmol/L). Decreased potassium may occur due to hyperaldosteronism secondary to sodium loss; hypokalemia may also be a consequence of hypomagnesemia, leading to disruption of the transport systems that control potassium excretion [12]. With hypokalemia, there is a risk of heart rhythm disturbances.

A common mistake is the recommendation to take large volumes of hypotonic liquid orally to correct water and electrolyte metabolism; this leads to an increase in the volume of losses through the stoma. The same effect is observed when taking hypertonic glucose solutions, drinks with sweeteners, tea, coffee, alcohol, and fruit juices.

For patients with a jejunostomy, it is optimal to take isotonic rehydration solutions with a sodium concentration of ≈90 mmol/L (since the sodium concentration in the jejunostomy discharge is ≈100 mmol/L). The composition of rehydration solutions per 1 liter of plain water, recommended by WHO, includes: sodium chloride 60 mmol (3.5 g); sodium bicarbonate (or citrate) 30 mmol (2.5 g or 2.9 g, respectively); glucose 110 mmol (20 g). Alternative composition: sodium chloride 120 mmol (7 g), glucose 44 mmol (8 g). Examples of ready-made solutions for oral rehydration, generally corresponding to the composition recommended by WHO - Regidron, Oralit.

The volume of hypotonic fluid taken orally should not exceed 500 ml/day. It is recommended to eat solid and liquid foods separately (with an interval of at least half an hour).

If there is a large volume of discharge from the jejunostomy (more than 2 liters), it is advisable to completely exclude the consumption of food and liquids orally for 2-3 days, which usually leads to a decrease in the volume of losses. An isotonic solution is administered intravenously in a volume of 2-4 l/day. The amount of daily urine should be at least 800 ml, and the sodium concentration in the urine should be at least 20 mmol/l. To maintain normal levels of potassium in the blood, correction of the balance of sodium and magnesium is of primary importance.

With a discharge volume of 1.5-2 l/day. It is recommended to drink a glucose-saline solution, and when taking a hypotonic liquid, adding salt to the food (approximately 7 g, ≈2/3 teaspoon of table salt per day). If the volume of discharge is borderline (1-1.5 l/day), it can be recommended to drink regular liquid in a volume of less than 1 l and adding salt to the food.

Adequate rehydration, which helps prevent the development of secondary hyperaldosteronism, is the most important step in the prevention and correction of hypomagnesemia. Magnesium salts are poorly absorbed from the gastrointestinal tract and may worsen diarrhea. When administered orally, preference is given to magnesium oxide in gelatin capsules at night, when intestinal transit is slowest. Excessive fat content in food should be avoided. If there is insufficient compensation for hypomagnesemia, 1-a-hydroxycholecalciferol is added in a gradually increasing dose (0.25-9.0 mcg/day). If it is necessary to prescribe magnesium sulfate parenterally, it is administered together with a solution of sodium chloride.

Correction of protein-energy deficiency during jejunostomy involves selecting a diet containing fats in the form of triglycerides and carbohydrates in the form of polysaccharides, which prevents an increase in food osmolarity. It is desirable that the concentration of sodium chloride in food is 90-120 mmol/l. The administration of an elemental diet (containing nutrients in an easily assimilated form - in the form of amino acids, oligopeptides, glucose, trace elements, dextrins, vitamins) has no advantages; on the contrary, it helps to increase the osmolarity of food and contains little sodium.

Medicines that suppress intestinal motility and secretion. If the above measures are insufficiently effective, they resort to medications that reduce the volume of discharge by inhibiting motility and/or secretion.

The treatment program for diarrhea in short bowel syndrome and intestinal stomas includes agonists of peripheral intestinal opioid receptors (loperamide, codeine phosphate, diphenoxylate). Drugs of this class slow down the passage of contents through the intestines by inhibiting propulsive contractions and stimulating segmental contractions. Accordingly, the degree of absorption of water and electrolytes increases. Opioid agonists also directly reduce the secretion of water and electrolytes and increase the tone of the ileocecal and anal sphincters.

Studies have shown that loperamide and codeine phosphate, by suppressing intestinal motility, reduce the volume of discharge from the ileostomy by 20-30% [14].

In one study, loperamide was administered at a dose of 4 mg 4 times a day. was more effective than codeine phosphate at a dose of 60 mg 4 times / day in reducing the volume of discharge through the stoma and sodium loss. The effect of co-administration of loperamide and codeine may be more pronounced.

According to British experts, the use of loperamide for short bowel syndrome is more preferable, since it does not have a central sedative effect and, as special studies have shown, does not cause fat malabsorption [14].

Loperamide has low systemic absorption when taken orally and does not penetrate the blood-brain barrier, so the risk of central side effects of the drug, including narcotic effects, is minimal.

As stated in the “Recommendations of the British Society of Gastroenterology” (2006), for short bowel syndrome, it is advisable to take the drug one hour before meals at a dose of 2-8 mg, the average dose is

16 mg/day. (in 4 doses). Given the frequent disruption of enterohepatic circulation of drugs after intestinal resection, it may be necessary to increase the dose of loperamide to 12-24 mg per single dose [14]. Increasing the dose must be carried out under the supervision of a doctor!

A number of randomized placebo-controlled studies have been conducted that convincingly prove the effectiveness and high safety of loperamide (Imodium) in the treatment of diarrhea in patients who have undergone intestinal surgery with various types of anastomoses and stomas [9,10,15,17,18].

The use of the combination of diphenoxylate and atropine is limited due to side effects associated with the anticholinergic effects of atropine.

In cases where tablets or capsules are released unchanged from the jejunostomy, their contents should be pre-mixed with food or water. For this category of patients, the ideal treatment option is lozenges, a unique dosage form of loperamide (Imodium). They instantly (in 2-3 seconds!) dissolve on the tongue and have a pleasant minty taste.

In cases of hypersecretion - when the volume of discharge exceeds 2-3 l/day. - the prescription of antisecretory agents is indicated: H2-blockers, proton pump inhibitors, octreotide, long-acting somatostatin/octreotide preparations. When the length of the jejunum is less than 50 cm, omeprazole should be administered intravenously.

If the ileum is preserved, mineralocorticoid preparations (fludrocortisone, aldosterone) or hydrocortisone can have a good effect in relieving diarrhea.

Alternative treatments. Data are accumulating on the effectiveness of the use of mucosal growth factors and hormone regulators (in particular, glucagon-like peptide-2) in stimulating adaptive processes after intestinal resection.

The introduction of short-chain fatty acids into the diet stimulates adaptation of the small intestine and significantly increases the absorption of amino acids [2]. Parenteral administration of glutamine and arginine, subcutaneous administration of growth hormone also accelerates the adaptation process [4,19].

Intestinal transplantation is a surgical treatment method that is indicated for patients with severe CI that cannot be corrected with conservative therapy (in particular, with a very short segment of jejunum - less than 50 cm, with severe motility disorders), as well as for patients with dangerous complications of parenteral nutrition (recurrent infection, progressive liver damage, etc.). Transplantation is also indicated when extensive bowel resection is necessary. More than 1,200 such operations have been performed worldwide. In some cases, a transplantation of the liver-small intestine complex and even a multivisceral transplantation (with the stomach and pancreas) is required.

Intestinal transplantation presents significant difficulties due to the high incidence of septic complications and low patient survival. Complications are caused by the temporary loss of the protective functions of the developed immune system of the intestinal mucosa and the presence of a non-sterile environment inside the lumen of the transplanted intestine. Immunosuppressive therapy includes tacrolimus-based regimens and antilymphocyte induction therapy. Today, intestinal transplantation is associated with survival within a year in 80% of patients, within 5 years - in 50% of patients, and in most cases without parenteral nutrition. The quality of life is comparable to that in uncomplicated CI.

Alternative surgical methods have been proposed to slow down peristalsis, in particular, reversion of a short segment of the small intestine, the essence of which is to “rotate” a section of the intestine that begins to contract in a retrograde direction.

Literature 1. Ivashkin V.T., Sheptulin A.A., Sklyanskaya O.A. Diarrhea syndrome. M., 2002. 164 p. 2. Nechaev V. M., Ivashkin V. T., Myagkova L. P. Short bowel syndrome. https://www.gastrosite.ru/articles. 3. American Gastroenterological Association medical position statement. Short bowel syndrome and intestinal transplantation. Gastroenterology 2003; 124: 1105-10. 4. Bustos D., Pons S., Pernas JC et al. Fecal lactate and short bowel syndrome // Dig. Dis. Sci. - 1994. - Vol. 39, N 11. - P. 2315-2319. 5. Cagir B. Short-Bowel Syndrome. // Site name: URL: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/193391-overview (April 4, 2010). 6. Caldarini MI, Pons S, D'Agostino D et al. Abnormal fecal flora in a patient with short bowel syndrome. An in vitro study on the effect of pH on D-lactic acid production // Dig. Dis. Sci. - 1996. - Vol. 41, N 8. - P. 1649-1652. 7. Goodlad RA., Nightingale JMD., Playford RJ. Intestinal adaptation. In: Nightingale JMD., eds. Intestinal failure. Greenwich: Greenwich Medical Media Limited, 2001. 8. Gouttebel MC, Saint-Aubert B, Astre C, et al. Total parental nutrition needs in different types of short bowel syndrome. Dig Dis Sci 1986; 31: 718-23/ 9. King RFGJ, Hill GH Effect of loperomide and codeine phosphate on ileostomy output. // Clinical Research Reviews - 1981, 1 (Suppl.1), 207-213. 10. Levitt MD, Jenner DC, Maher MJ. High dose loperamide suppositories: a novel approach for improving clinical function after restorative proctocolectomy. //Aust NZJ Surg. 1995 Dec;65(12):881-3. 11. Nightingale JMD. Introduction. Definition and classification of intestinal failure. In Nightingale J.M.D., eds. Intestinal failure. Greenwich: Greenwich Medical Media Limited, 2001. 12. Nightingale JMD, Lennard-Jones JE, Walker ER, et al. Jejunal efflux short bowel syndrome. Lancet 1990; 336: 765-8. 13. Nightingale JMD, Lennard-Jones JE, Gerthner DJ, et al. Colonic preservation reduces the need for parenteral therapy, increases the incidence of renal stones but does not change the high prevalence of gallstones in patients with a short bowel. Gut 1992; 33:1493-7. 14. Nightingale J, Woodward JM; Small Bowel and Nutrition Committee of the British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for management of patients with a short bowel. // Gut. 2006 Aug;55 Suppl 4:iv1-12. 15. Shee CD, Pounder RE Loperamide, diphenoxylate, and codeine phosphate in chronic diarrhea. // Br Med J. 1980 Feb 23;280(6213):524. 16. Simons BE., Jordan GL. Massive bowel resection. Am J Surg 1969; 118:953-9. 17. Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K. Loperamide and ileostomy output-placebo-controlled double-blind crossover study. // Br Med J. 1975 Jun 21;2(5972):667. 18. Tytgat GN, Huibregtse K, Dagevos J, van den Ende A. Effect of loperamide on fecal output and composition in well-established ileostomy and ileorectal anastomosis. // Am J Dig Dis. 1977 Aug;22(8):669-76. 19. Wilmore DW, Lacey JM, Soultanakis RP et al. Factors predicting a successful outcome after pharmacologic bowel compensation // Ann. Surg. - 1997. - Vol. 226, N 3. - P. 288-292. 20. Windsor CWO., Fejfar J., Woodward DAK. Gastric secretion after massive small bowel resection. Gut 1969; 10: 779-86. 21. Yokoyama K., Ogura Y., Kawabata M., et al. Hyperammonemia in a patient with short bowel syndrome and a chronic renal failure. Nephron 1996; 72: 693-5. 22. Zurier RB., Campbell RG., Hashim SA., et al. Use of medium-chain triglyceride in management of patients with massive resection of the small intestine. N Engl J Med 1966; 274:490-3.

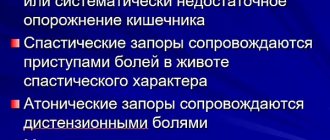

Symptoms of the pathological process

After a bowel resection, a person may experience the following symptoms for several weeks or months, which are characteristic of the first stage of short bowel syndrome:

- frequent loose stools;

- dehydration due to diarrhea;

- metabolic disorders;

- weakness and frequent drowsiness;

- weight loss;

- mental and neurological disorders.

After recovery due to partial or complete resection of the intestine, a period of subcompensation follows, which is characterized by normalization of stool and metabolism. The duration of the second period of short bowel syndrome is about a year.

After surgery and recovery, the body adapts to the new intestine. The duration of this stage depends on the condition of the patient with short bowel syndrome, age, extent of surgery and other factors.

The most unfavorable is the last stage of short bowel syndrome, in which the patient experiences debilitating diarrhea (about 15 trips to the toilet per day), rapid weight loss, persistent metabolic disorders, anemia and mental disorders.

Bacterial overgrowth syndrome

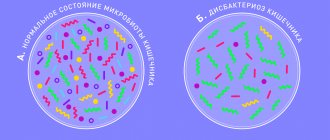

Bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SIBO) is a pathological condition characterized by an increase in the number of bacteria in the small intestine with the development of diarrhea and impaired absorption of certain nutrients.

This condition/disease in the domestic literature is often called a special case of intestinal dysbiosis/dysbiosis.

Prevalence of SIBO

The worldwide prevalence of this syndrome remains unknown. In the literature, the incidence of SIBO is most often assessed in various diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) and other organs. In particular, it is known that SIBO is observed in 38% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome and in 50-60% of patients with cirrhosis of the liver. Often this pathological syndrome is detected in people suffering from inflammatory bowel diseases, systemic connective tissue diseases (for example, scleroderma), endocrine pathologies (diabetes mellitus), etc.

Causes and mechanisms of development of SIBO

Normally, different sections of the digestive tube have different species and quantitative composition of the microorganisms that populate them. For example, in the stomach and upper parts of the small intestine, the microbial composition is quite poor, limited to a small (103-104 colony-forming units (CFU) per milliliter of aspirate) number of bacteria, among which lactobacilli, enterococci and some other aerobic bacteria predominate.

In the terminal sections of the small intestine, primarily in the terminal ileum, the number and diversity of microorganisms increases. In this transition zone between the small and large intestines, the number of microorganisms increases to 107-109 CFU/ml. The main bacteria detected in this region are represented by lacto- and bifidobacteria, streptococci, bacteroides, etc.

Finally, the large intestine is the “residence” of anaerobic bacteria that do not require oxygen to function (bacteroides, bifidobacteria, enterococci and clostridia, lactobacilli, E. coli, streptococci, staphylococci, etc.). The number of microorganisms in this section of the intestine is maximum and can reach 1012 CFU/ml.

The quantitative and qualitative microbial composition in different parts of the gastrointestinal tract is maintained by several mechanisms. This includes the acidic environment of the stomach, the bactericidal effect of bile in the small intestine, as well as preserved motility of the stomach and intestines. The normal motor and closing function of the gastrointestinal sphincters, such as the pyloric sphincter (valve between the stomach and duodenum) and the ileocecal valve (between the ileum and colon), is very important.

Disruption of this regulation leads to an increase in the number of microorganisms in the small intestine, and this leads to various digestive disorders. This condition is called SIBO or small intestinal bacterial overgrowth syndrome .

The main reasons for the development of SIBO:

- Conditions leading to a decrease in the production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach - hypo- and achlorhydria against the background of atrophic or autoimmune gastritis, due to the use of drugs from the group of H2-histamine blockers and proton pump inhibitors;

- Impaired motility of the stomach and/or small intestine - often observed in diabetes mellitus, liver cirrhosis, chronic renal failure, scleroderma, polymyositis, celiac disease, Crohn's disease, etc.;

- Anatomical disorders - consequences of surgical interventions (resection of the stomach, ileocecal valve, etc.), diverticula of the small intestine, strictures of the small intestine of any origin, etc.;

- The use of antibiotics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, cytostatics, steroid hormones, tricyclic antidepressants, opiates, etc.;

- Immune disorders, including deficiency of secretory immunoglobulin A;

- Chronic pancreatitis with exocrine pancreatic insufficiency;

- Chronic alcohol abuse;

- Old age and old age increase the risk of SIBO.

The consequence of an increase in the number of small intestinal microorganisms is:

- reduction in the content and activity of intraluminal and parietal enzymes due to their destruction by bacteria;

- insufficient breakdown of nutrients, impaired absorption and an increase in the liquid part of the intestinal contents with the development of diarrhea;

- premature deconjugation of bile acids in the initial parts of the small intestine with the development of chemical damage to the small intestinal mucosa and diarrhea.

Due to malabsorption in the small intestine, a deficiency of certain micro- and macroelements, as well as vitamins (for example, vitamin B12) develops.

Symptoms of SIBO

- Bloating and/or increased gas production is the most common symptom;

- Loose stools – from pasty 1-2 times a day to liquid several times a day;

- Constipation is rare, but does not exclude the diagnosis of SIBO;

- Mild abdominal pain (often accompanied by increased gas formation) - usually localized in the umbilical region;

- Feeling of “transfusion” or rumbling in the stomach;

- Weight loss is possible with severe and prolonged SIBO;

- Various complaints caused by a deficiency of micro-, macroelements and vitamins.

Diagnosis of SIBO

A typical clinical picture of the disease and anamnesis (for example, an indication of the use of antibiotics) allows one to suspect the diagnosis of SIBO. The results of additional tests are confirmed.

Due to the fact that SIBO is associated with an increase in the number of bacteria in the small intestine, the use of the traditional stool test for dysbiosis/dysbiosis in our country to diagnose this syndrome is not valuable. When studying the bacterial composition of stool, this method evaluates samples of stool from the colon. The analysis includes the identification of only 20 types of bacteria, while more than 1,000 have been identified in the human intestine.

For scientific purposes and large medical centers, the liquid contents (aspirate) of the duodenum are used for diagnosis. This aspirate can be cultured on special media to identify aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and determine the number of CFU. An alternative is the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) method, which also determines the quantity (less often the qualitative composition) of small intestinal bacteria and other microorganisms.

According to the most modern recommendations, if the number of microorganisms in the aspirate from the small intestine increases by more than 103 CFU/ml, the likelihood of SIBO is high. Alas, the proposed research methods are expensive and cannot be used in routine practice.

While the quantitative characteristics of SIBO are more or less clear, qualitative changes in the bacterial composition of the small intestine in this condition remain poorly understood. There is only a small number of studies on certain diseases (for example, irritable bowel syndrome), where certain changes in the ratios of some groups of bacteria to others have been identified. The clinical significance of such changes is still unclear.

Currently, most recommendations suggest using a lactulose or glucose hydrogen breath test to diagnose SIBO. Normally, hydrogen is produced only by intestinal bacteria during the processing of certain carbohydrates. The resulting hydrogen is absorbed into the bloodstream, reaches the lungs and can be determined by a special analyzer in the exhaled air. The test evaluates the change in hydrogen concentration after ingesting a carbohydrate solution. The non-absorbable carbohydrate lactulose is most often used as a test substrate; glucose is used less frequently.

In some individuals, SIBO symptoms may be caused by an overgrowth of methane-producing microorganisms, in which case a methane breath test may be used.

There are other breath tests, but they are not readily available in routine practice.

SIBO Treatment

Currently, SIBO is considered a secondary condition that occurs as a consequence of an existing “background” disease or external influence (including drug therapy). Therefore, in all recommendations for the treatment of SIBO, the first place is to treat the underlying disease to prevent the recurrence of complaints.

One of the main methods of treating SIBO is the so-called “sanitation” of the intestines by prescribing antibiotics. Preference is given to non-absorbable antibiotics (for example, rifaximin) and other antibacterial drugs that have proven their effectiveness.

Diet therapy that restricts foods rich in fermentable carbohydrates (called a lowFODMAP diet) may be effective in some patients.

Prescribing pre- and probiotics as additional means of correcting SIBO can reduce some of the symptoms - bloating, abdominal discomfort. However, these drugs are rarely effective as sole therapy.

Also, in the treatment of SIBO, additional medications are often used, such as multienzyme drugs, intestinal motility regulators, sorbents, etc.

SIBO Forecast

In most cases, SIBO progresses favorably. When the causative factor that caused SIBO is eliminated, in the case of properly selected therapy, the patient is completely cured. However, if the conditions for the development of SIBO persist (chronic disease, previous surgery, etc.), relapses of symptoms are possible, requiring repeated courses of treatment.

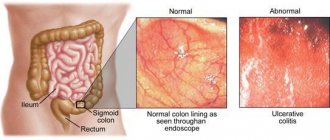

How is diagnosis carried out?

If you suspect short bowel syndrome, you should immediately contact a gastroenterologist. The specialist interviews the patient, specifying how long ago the intestinal resection was performed, inquires about the complexity of the disease and conducts an external examination of the patient. For short bowel syndrome, a comprehensive diagnosis is important, including the following procedures:

- Collection of urine and blood for general and biochemical analysis. With intestinal pathology, the result is anemia, inflammation, lack of vitamins and low protein levels.

- X-ray of the small intestine using barium passage.

- Performing a coprogram to identify particles of food and fat that have not been digested by the intestines.

- Examination of the intestine using ultrasound.

- Gastroduodenoscopy to examine the intestinal mucosa.

- Measurement of the pH level of intestinal secretions, since in patients with the syndrome, the content of hydrochloric acid in the intestine increases.

- Colonoscopy, which allows you to assess the condition of the intestines and notice pathological processes or changes in the internal organs.

With short bowel syndrome, the doctor must palpate the patient's abdomen to detect bloating and tenderness. Complex diagnostics makes it possible not only to assess the condition of the intestine, but also to identify symptoms of concomitant acute or chronic diseases.

Publications in the media

Dumping syndrome is a pathological condition that occurs after gastric resection (especially according to the Billroth-II modification), gastrectomy, vagotomy, pyloroplasty due to the rapid entry of gastric contents into the small intestine.

Statistical data. The frequency after selective proximal vagotomy is 0.9% of operated patients; after truncal vagotomy with pyloroplasty - 10–22% of cases; in women after gastrectomy - up to 100%.

Classification • By time of occurrence •• Early dumping syndrome (signs appear within 30 minutes after eating) •• Late (hypoglycemic) dumping syndrome (2 hours after eating) • By severity •• Mild degree (dumping reaction occurs only after dairy and sweet dishes): slight weakness, increased heart rate by 10–15 per minute; duration of attack - up to 30 minutes; body weight deficiency - no more than 5 kg; ability to work is preserved •• Moderate degree (dumping reaction occurs when taking any food, at the height of the reaction the patient is forced to lie down): increased heart rate by 20–30 per minute; Blood pressure with a tendency to increase the systolic component; duration of attack - up to 1 hour; body weight deficiency - up to 10 kg; ability to work is reduced •• Severe degree (dumping reaction develops when eating any food): patients eat while lying down and are in a horizontal position for up to 2–3 hours after eating; increased heart rate by more than 30 per minute; Blood pressure is labile, sometimes bradycardia, arterial hypotension, collapse; body weight deficiency - more than 10 kg; ability to work is lost.

Risk factors: drainage operations, gastric resection.

Pathogenesis • Rapid entry into the upper part of the small intestine of food with high osmolarity leads to the movement of extracellular fluid into the lumen, stretching of the intestinal wall and the release of biologically active substances: histamine, serotonin, bradykinin. As a result: vasodilation, decrease in blood volume, increased intestinal motility • Another form of dumping syndrome (reactive hypoglycemia) is associated with a sharp increase in glucose levels after a meal. A rapid increase in blood glucose concentration stimulates the release of insulin. However, by this time (approximately 2 hours after eating), the food taken has already been utilized, and the delayed action of insulin causes clinical signs of hypoglycemia. Against the background of hypoglycemia, the content of electrolytes, especially potassium, in the blood serum changes.

Clinical manifestations • Attacks of weakness during meals or 15–20 minutes after it • Drowsiness, dizziness, tinnitus, trembling of extremities • Feeling of abdominal discomfort, pain • Flatulence • Nausea • Diarrhea • Palpitations • Increased sweating • Loss of body weight • Transient erythema • Confusion and fainting • The severity of dumping syndrome symptoms decreases in the supine position. On the contrary, foods rich in carbohydrates increase symptoms.

Research methods • Provocative test. Dumping syndrome can be triggered by taking 150 ml of 50% glucose or sugar solution. In this case, the patient should not lie down • X-ray of the stomach: immediate emptying of the stomach from the contrast mass is detected • Blood test: afternoon hypoglycemia, signs of anemia, hypoalbuminemia • The drug that affects the results is insulin; disease affecting the outcome: diabetes.

Differential diagnosis • Partial intestinal obstruction • Gastrocolic fistula • Chronic enteritis • Sprue • Crohn's disease • Insulinoma • Pancreatic secretory insufficiency • Neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoid).

TREATMENT

Conservative treatment • Diet. Diet No. 1 is prescribed, containing 130 g of proteins, 100 g of fats, 350–400 g of carbohydrates (30 g of sugar). It is possible to completely eliminate sugar and replace it with xylitol or sorbitol. To reduce the rate of evacuation of food from the gastric stump, viscous and jelly-like dishes are prepared. It is advisable to eat solid and liquid foods separately. Meals - at least 6 times a day. After eating, it is advisable to lie down for about 30 minutes • To reduce the reaction to the rapid entry of food into the small intestine, procaine, anesthesin, and antihistamines are prescribed before meals • Octreotide 200–400 mg/day subcutaneously in equal doses every 8 hours • Replacement therapy: gastric juice, hydrochloric acid, panzinorm forte, pancreatin, pancreatin+bile components+hemicellulase, vitamins • Other methods •• Anticholinergic drugs (for example, atropine, platyphylline) are usually ineffective •• For nutritional disorders - blood transfusions and blood substitutes •• Psychotherapy.

Surgical treatment • Indications for surgery: severe dumping syndrome in case of ineffective nutritional therapy and long-term complex drug treatment • Surgical intervention consists of reduodenization with gastroduodenoplasty. The small intestinal transplant slows down the emptying of the gastric stump, the inclusion of the duodenum improves digestion and in some patients can reduce the intensity of the dumping reaction.

Complications • Hypoglycemia • Nutritional disorders • Electrolyte disturbances, including hypokalemia • Anemia.

Concomitant pathology • Peptic ulcers • Reactive hypoglycemia • Adhesive disease of the peritoneum • Chronic pancreatitis • Chronic enteritis • Biliary dyskinesia.

Prevention: widespread use of organ-preserving operations (for example, selective proximal vagotomy) in the treatment of duodenal ulcer. If gastric resection is necessary, one should strive to apply direct gastroduodenoanastomosis.

Synonyms • Postgastroresection syndrome • Disease of the operated stomach • Agastric asthenia • “Small stomach” syndrome • Dropping syndrome

ICD-10 • K91.1 Syndromes of the operated stomach