Esophagitis is an inflammatory process in the esophageal wall. The pathology affects the mucous membrane of the organ, and as it progresses, it penetrates into its deeper tissues. In gastroenterological practice, esophagitis is the most common among esophageal disorders. It develops as an independent disease or against the background of other disorders.

Esophagitis in children occurs in acute or chronic form:

- the first form is characterized by a pronounced clinical picture and develops against the background of a direct effect on the inner lining of the esophagus;

- symptoms of esophagitis in children with a chronic course are characterized by mild symptoms. The pathology progresses gradually against the background of other disorders and can threaten the formation of stenosis - narrowing of the lumen of the esophagus.

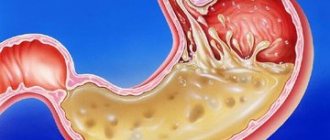

The most common forms of reflux esophagitis in children are catarrhal and edematous. The depth of the lesion also varies and can affect from superficial layers to deep submucosal tissues, accompanied by bleeding. Therefore, when this disease is detected, immediate treatment is necessary.

If a child is diagnosed with reflux disease, is it forever?

Or can this be cured?

What will happen to reflux when the child grows up?

These are some of the most frequently asked questions from parents at my appointments.

I'll try to clarify the situation.

The first thing I want to do is separate reflux in infants from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) in older children.

Gastroesophageal reflux in children under one year of age is very common, is considered mostly benign and almost always goes away on its own.

That is, the prognosis is the most optimistic, even without the intervention of doctors or with minimal help in the form of nutritional correction.

If we talk about reflux in children after one year, then not everything is so simple.

When symptoms persist in children older than 12 to 18 months (the timing is debated) or appear for the first time at an older age, then we can talk about reflux disease (GERD) - a chronic condition with potential risks.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children

Shcherbakov P.L.

Although chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract are the most common pathology occurring in both adults and children, the total number of children suffering from diseases of the digestive system has changed little in recent years. Thus, if in 1999 the incidence of diseases of the digestive system was 12,000 per 100 thousand children, then in 2006 it was 12,217 children per 100 thousand children [1]. The total absolute number of children suffering from diseases of the digestive system was 3,300,834, of which 1,821,990 were newly diagnosed in 2006. Despite the fairly large total number of patients, the structure of the pathology has changed significantly, so, in particular, the total number of children suffering from peptic ulcer disease has decreased to 16,130 people, and children with gastritis or duodenitis have become 622,279. This increase is due to many factors underlying basis for the development of inflammatory diseases of the digestive system. In particular, these traditionally include nutritional, allergic, immune, and neuropsychiatric. However, all these reasons rather create a certain background against which the main events develop, rather than being true triggering factors [2]. Most of the pathology of the digestive organs occurs due to inflammatory changes in the mucous membrane of the upper digestive tract. In turn, inflammatory diseases of the upper digestive tract are predominantly acid-dependent diseases. Acid-dependent diseases are diseases in which the decisive link in the pathogenesis is the hyperproduction of hydrochloric acid by the stomach. These, in particular, include conditions such as gastric and duodenal ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux disease, Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, NSAID-induced gastropathy, and functional dyspepsia.

In a wide range of chronic inflammatory diseases of the gastrointestinal tract observed in children of different ages, lesions of the esophagus occupy an increasingly important place. If until recently, among lesions of the esophagus, gastroenterologists more often noted various anomalies and malformations, injuries to the mucous membrane as a result of predominantly thermal or chemical damage, as well as long-term consequences of these injuries, now changes in the mucous membrane of an inflammatory nature are increasingly common.

In the spectrum of chronic inflammatory diseases of the digestive system, isolated esophagitis accounts for slightly less than 1.5%. More often, inflammation of the esophagus is combined with damage to other organs and systems. In particular, with gastritis, combined damage to the esophagus is detected in 15% of children, with gastroduodenitis - in 38.1%. With duodenal ulcer, esophagitis occurs in almost all children [3].

In the overwhelming majority, the cause of the inflammatory process in the esophagus is the reflux of acidic contents from the stomach into the esophagus. That is why the inflammatory process that occurs in the esophagus is called reflux esophagitis or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

The concept of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children refers to damage to the esophagus as a result of the reflux of acidic stomach contents into the esophagus. There are physiological and pathological gastroesophageal reflux. With physiological reflux, a rare and short-term reflux of acidic contents from the stomach into the esophagus occurs without damage to the mucous membrane and, accordingly, without any clinical manifestations (mainly after a heavy meal or during sleep). With pathological reflux, frequent and prolonged reflux of acidic contents into the esophagus is accompanied by the development of an inflammatory reaction of the esophageal mucosa with pronounced clinical manifestations.

Gastroesophageal reflux can occur in children of any age. The clinical manifestations of the disease largely depend on the age of the child. Thus, in children of the first year of life, “extraesophageal” manifestations predominate in the form of respiratory disorders (cough, dysphonia, asthma attacks), as well as vomiting and regurgitation syndrome. As the child grows, “esophageal” manifestations of reflux come to the fore. More than 60% of children with damage to the esophagus have characteristic clinical signs, which include dull, aching pain in the epigastric region and behind the sternum, intensifying immediately after eating and weakening somewhat over the next 1.5-2 hours, as well as various dyspeptic symptoms. manifestations of the so-called “upper dyspepsia”: swallowing disorders (dysphagia), belching (often sour, air or eaten food), periodic hiccups, nausea, vomiting. In young children, the “wet pillow” symptom is detected as a manifestation of passive regurgitation. The most common complaint presented by children with diseases of the esophagus is heartburn, the clinical picture of which is clearly described by older children. However, young children cannot always describe their sensations with the specific term “heartburn.” Only a correctly collected anamnesis allows you to specify the child’s unpleasant sensations in the form of a “stove” or “burning” in the chest.

Quite often, pathology of the upper digestive tract is observed in children with bronchial asthma. The presence of pathological gastroesophageal reflux serves as a provoking factor in the development of attacks of bronchial asthma, mainly at night. If a few years ago it was believed that the main cause of the development of respiratory pathology was only aspiration (or microaspiration) of stomach contents during reflux, now the leading role of autonomic disorders arising from gastroesophageal reflux has been proven in the development of such cardio-respiratory symptoms as reflex central apnea, reflex bradycardia, reflex bronchospasm, reflex laryngospasm.

The prerequisites for the development of pathological reflux in children are varied. The main one is: the reflux of hydrochloric acid, pepsin and bile acids from the stomach into the esophagus, caused primarily by a decrease in the motor activity of the esophagus and a weakening of the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and the occurrence of antiperistaltic waves, accompanied by gastroesophageal prolapse and reflux.

Weakening of the antireflux mechanism of the lower esophageal sphincter can be primary or secondary. Secondary sphincter weakness most often occurs against the background of inflammation or other organic changes in the underlying digestive organs (developing edema of the duodenal bulb during peptic ulcer disease or the formation of stenosis of the bulbo-duodenal junction), various systemic diseases (scleroderma). As a result of disruption of the movement of chyme through the bulb, acidic contents accumulate in the stomach and, as a consequence, the appearance of gastroesophageal reflux and the development of esophagitis. Similar changes can occur in children of the 1st year of life with anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract, manifested by pseudo-obstruction (pyloric stenosis/pylorospasm, duodenal membranes, annular pancreas), the development of antiperistaltic activity (hiatal hernia). A decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter can occur with the use of various drugs (anticholinergics, caffeine, adrenergic blockers, nitrates, theophylline, calcium channel blockers (verapamil, nefidipine), opiates), nicotine, alcohol and certain foods (chocolate, coffee, fats, spices). The occurrence of GERD can, to some extent, be facilitated by eradication therapy carried out for chronic inflammatory diseases of the VOPT (gastritis, peptic ulcer) associated with H. pylori infection. As a result of numerous studies, it has been shown that H. pylori in the first 10-12 years of invasion on the surface of the gastric mucosa stimulates the process of acid formation [4,5]. At the same time, under the influence of these microorganisms, the motor activity of the stomach is activated, as a result of which stagnation of acidic contents does not occur. After eradication therapy, the peristaltic activity of the stomach decreases while maintaining a relatively high level of acid production in children. Therefore, one of the reasons for the occurrence of reflux esophagitis in children may be the reflux of acidic contents that accumulate in the stomach after eradication of H. pylori [6,7].

The primary failure of the antireflux mechanisms in young children, as a rule, is based on disturbances in the regulation of the esophagus by the autonomic nervous system.

Recently, children have been experiencing significant psycho-emotional stress, which contributes to the earlier development of autonomic dystonia syndrome. Children with intense mental overload more often complain of belching and heartburn; upon special examination, gastroesophageal prolapse is significantly more often detected in them.

The formation of the sphincter apparatus occurs in children by the age of 5-7 years [8]. At the same time, children from 5 to 13 years old have a significantly higher acid-producing function of the stomach compared to adults. Therefore, failure of the sphincter apparatus in children with increased acid-producing function of the stomach can lead to the “flowing” of acidic contents into the esophagus, which contributes to the development of terminal esophagitis in them with hyperemia of the mucous membrane, mainly along the posterior wall with the characteristic appearance of “tongues of flame” or “octopus tentacles” determined by endoscopic examination.

Depending on the severity of the inflammatory process, several degrees of esophagitis are distinguished. Currently, there are various classifications of esophagitis. The most widely used is the Los Angeles Classification System (1996) [9], which was based on endoscopic changes in the esophageal mucosa.

Existing classifications may not always accurately reflect the condition of the esophageal mucosa in children. Therefore, to assess the condition of the esophagus in children, the G. Tytgat classification, modified by V.F., was proposed in 1999. Privorotsky et al. According to this classification, there are 4 degrees of esophagitis [10]:

- 1st degree. Moderate focal erythema and (or) friability of the mucous membrane of the abdominal esophagus. Moderately expressed motor disturbances in the area of the LES (raising of the Z-line up to 1 cm), short-term provoked subtotal (along one of the walls) prolapse to a height of 1-2 cm, decreased tone of the LES.

- 2nd degree. The same + total hyperemia of the abdominal esophagus with focal fibrinous plaque and the possible appearance of single superficial erosions, often linear in shape, located at the tops of the folds of the esophageal mucosa. Motor disturbances: clear endoscopic signs of NCJ, total or subtotal provoked prolapse to a height of 3 cm with possible partial fixation in the esophagus.

- 3rd degree. The same + spread of inflammation to the thoracic esophagus. Multiple (sometimes merging erosions), not circularly located. Increased contact vulnerability of the mucous membrane is possible. Motor disturbances: the same + pronounced spontaneous or provoked prolapse above the crura of the diaphragm with possible partial fixation.

- 4th degree. Esophageal ulcer. Barrett's syndrome. Esophageal stenosis.

Diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux is based both on clinical data, the results of endoscopic examination of the esophageal mucosa, and on data from intraesophageal pH-metry and sphinctromanometry.

The main method for diagnosing reflux esophagitis at the present stage is esophagogastroduodenoscopy with targeted biopsy of the esophageal mucosa. Endoscopy allows you to evaluate the nature of the mucous membrane, its color, the severity and prevalence of hyperemia, the presence of erosions, ulcers, fibrin deposits on the surface, the consistency of the cardiac sphincter, swelling of the folds of the esophagus and cardiac sphincter, and vascular pattern. Histological examination of a biopsy of the mucous membrane makes it possible to accurately determine the severity of the inflammatory process and the presence of foci of gastric metaplasia. To assess the tone of the LES and the state of motor function of the stomach, sphincteromanometry is used. A manometric sign of gastroesophageal reflux is not only a change in the nature of contractions of the esophagus, but also a decrease in the amplitude of contractions, an increase in their duration, and deformation of the shape of the contractile complex. A daily study of the pH of the esophagus allows us to identify the total number of reflux episodes during the day, their duration (normal pH values of the esophagus are 5.5-7.0, in the case of reflux <4). The diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease is justified when the total number of refluxes increases to more than 50 during the day and/or when the pH in the esophagus decreases below 4 for a total duration of more than one hour. The use of multichannel pH meters with 3-5 sensors makes it possible to identify not only the duration, but also the height of the reflux, which is important when studying reflux-related diseases of the respiratory system. A fairly sensitive and specific method for detecting gastroesophageal reflux is esophageal scintigraphy using technetium sulfate colloid. A slowdown in esophageal clearance is detected when the isotope is retained in the esophagus for more than 10 minutes. When conducting an X-ray examination of the esophagus with gastroesophageal reflux, reflux of the contrast agent from the stomach into the lumen of the esophagus, or a hiatal hernia, can be detected.

Treatment of esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease in children is complex and is based on three main principles:

- Diet therapy

- Postural therapy

- Drug therapy aimed at:

normalization of peristaltic activity of the esophagus and stomach,

- restoration and normalization of the acid-forming function of the stomach,

- restoration of the structure of the mucous membrane of the esophagus, combating inflammatory changes that occur in the mucous membrane.

Treatment of any disease of the digestive system, which includes gastroesophageal reflux disease, begins with nutritional correction. The basic principle of a rational diet is frequent, fractional meals using chemical and mechanical sparing of food. The last meal should be no later than 3-4 hours before bedtime. Infants are fed in small portions using special additives to nutritional formulas. Currently, special infant nutritional formulas have been developed that can be used for gastroesophageal reflux (Frisov, Nutrilon, Samper, etc.). Foods that increase peristalsis and gastroesophageal reflux (coffee, chocolate, fatty and spicy foods, etc.) are excluded from the diet of older children. Children should be explained the adverse effects of tobacco smoke and alcohol on the mucous membrane of the esophagus and the condition of the cardiac sphincter.

The basis of therapeutic measures for gastroesophageal reflux is postural therapy (position therapy), aimed at reducing the degree of reflux, rapid emptying of the esophagus from gastric contents, which reduces the risk of developing inflammation and respiratory complications. Postural therapy should continue not only during meals and a short period of time after it, but throughout the day, both day and night.

It is advisable to feed infants in a sitting position at an angle of 45-60°, which is supported with the help of special child seats. If reflux is severe in older children, it is recommended to eat while standing. To prevent the flow of gastric contents into the esophagus, older children with insufficiency of the lower esophageal sphincter are recommended to sleep on a bed with the head of the bed raised by 20 cm.

The use of medications in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease depends on the severity of clinical symptoms and inflammatory changes in the esophagus. In the absence of a clearly defined clinical picture, it is possible to use only drugs that normalize the motility of the gastrointestinal tract. Today, the most effective drugs with antireflux action are prokinetics - blockers of both central (at the level of the chemoreceptor zone of the brain) and peripheral dopamine receptors. These include metoclopramide and domperidone. These drugs enhance the motility of the antrum of the stomach, which promotes rapid gastric emptying and thereby increases the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. However, when metoclopramide is prescribed to young children, extrapyramidal reactions may occur, so these drugs should be prescribed with caution. Similar effects are practically not observed when using domperidone. The course of antireflux therapy is usually 10-14 days.

In the presence of clinical symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease, the use of drugs that regulate acid formation processes together with drugs that normalize gastrointestinal motility is indicated. The first-line drugs are antacids, which neutralize the acid found in the lumen of the stomach. In pediatric practice, modern aluminum and magnesium-containing drugs are used that have a “mild” effect on acid and have cytoprotective and reparative effects. These medications can be prescribed to children of any age due to their almost complete absence of side effects. The different composition of antacid drugs also determines the characteristics of their use in children. Thus, Maalox, containing balanced magnesium and aluminum hydroxide, normalizes the motility of not only the upper, but also the lower parts of the digestive tract, which justifies its primary use in children with constipation. The presence of agar-agar and pectin in the composition of phosphalugel gel determines its protective and reparative effect on the mucous membrane, therefore the use of this drug is indicated for severe signs of inflammation of the esophagus. The course of treatment with antacids depends on the severity of gastroesophageal reflux, inflammatory changes in the esophagus and averages from 10 to 21 days. The drugs are prescribed after 60-90 minutes. after meals, children under 6 months - 1/4 sachet or 1 teaspoon after each feeding, children over 6 months - 1/2 sachet or 2 teaspoons after each feeding, older children 1-2 sachets. However, given that antacid drugs act only on the already formed acid located in the lumen of the stomach, and their short duration of activity (no more than 90 minutes), they cannot be the main drug for the treatment of GERD.

With pronounced clinical manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease, an important role is played by antisecretory therapy. According to the mechanism of action on the parietal cell of the gastric mucosa, existing antisecretory drugs can be divided into two large groups - histamine H2 receptor blockers and H+, K+-ATPase blockers (proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). The use of histamine receptor H2 blockers leads to inhibition of H2 -histamine receptors on the surface of the parietal cell and reduces acid secretion. However, their therapeutic effectiveness is ensured by a high level of the drug in the blood, which sometimes requires repeated administration; suppression of gastric secretion is achieved by affecting only one type of receptor - histamine. In this case, hypersecretion may occur by stimulating others receptors (gastrin, acetylcholine) [11,12]. Rapid withdrawal of this drug can lead to the development of tolerance and “rebound” syndrome, which limits its widespread use in pediatric practice [13]. Dependence on various factors, inability to control the process of acid formation during days do not make it possible to recognize this group of drugs as the main one for the treatment of acid-related diseases. Ranitidine is prescribed 75-150 mg 1-2 times a day in courses lasting up to 3 months with gradual withdrawal.

The most effective drugs that successfully control the production of hydrochloric acid throughout the day, regardless of the stimulus acting on the receptors of parietal cells, are proton pump inhibitors. Proton pump inhibitors are substituted benzimidazole derivatives. In the tubules of parietal cells, they are converted into the active metabolite tetracyclic sulfenamide [14]. In this form, proton pump inhibitors form strong covalent bonds with the mercapto groups of the cysteine residues of H+,K+-ATPase, which blocks the conformational transitions of the enzyme, and it turns out to be “turned off.” Inhibition of H+,K+-ATPase by substituted benzimidazoles is irreversible. In order for the parietal cell to begin acid secretion again, the synthesis of new proton pumps, free from connection with the inhibitor, is necessary [15,16]. In this case, PPIs control both daytime, food-stimulated, and nighttime secretion of hydrochloric acid, regardless of the stimulus acting on the receptors of parietal cells. Thus, when taking this group of drugs, tolerance does not develop, and, in addition, after their withdrawal, “rebound” phenomena are not observed. Considering that the gastric epithelium (especially in children) is completely renewed every 2 weeks, the parietal cells are also renewed, thereby maintaining the potential ability of the gastric mucosa to produce hydrochloric acid. Proton pump inhibitors currently occupy a leading position in the treatment of acid-related diseases. These drugs entered the doctor’s arsenal relatively recently: the first proton pump inhibitor omeprazole appeared in 1988 (Losec® - AstraZeneca), then lansoprazole, pantoprazole and rabeprazole were created [16].

All these drugs, being absorbed in the duodenum and jejunum, go through a certain path, being metabolized to varying degrees in the liver, and in the form of active units the maximum accumulation of hydrogen ions is concentrated in the gastric mucosa. The main indicator of the action of proton pump inhibitors is the duration of maintenance of the drug concentration in the blood plasma. The “gold standard” for the effectiveness of PPIs is omeprazole. Omeprazole is widely used and has been used to treat gastroesophageal reflux disease in both adults and children from age 2 years onwards. In this case, the dosage of the drug is more than 1.5 mg/kg, and the duration of treatment exceeded 3 months [17-19].

However, proton pump inhibitors also have their drawbacks. While they suppress acid formation, they themselves have very low acid resistance. In particular, the half-life at pH 2 is less than 2 minutes, and the half-life at pH 7 is about 14 hours. Therefore, PPIs need protection of the active principle. As a rule, this problem is solved by using capsules made of dense gelatin or tablets coated with a multilayer shell. Unfortunately, in this form it is difficult to accurately dose the drug, especially for young children. Of the existing PPIs, only omeprazole has other forms - intravenous and MUPS form. MUPS - Multiple Unit Pellet System - a unique form of the drug, which is an acid-resistant magnesium-omeprazole, which, entering the alkaline environment of the duodenum, breaks down into omeprazole, which in turn is very quickly absorbed without loss, and magnesium, used by the body as an essential trace element . In addition to the fact that each unit of acid-resistant magnesium omeprazole is coated with an additional protective coating, microgranules of the active substance are compressed into one oblong tablet (MAPS). This tablet can be easily crushed, dissolved and the dose can be precisely selected for each individual patient. The latest generation of PPIs is esomeprazole, a purified levorotatory isomer of omeprazole. The effectiveness of its application significantly exceeds its prototype. Esomeprazole (Nexium® AstraZeneca, like omeprazole, has several release forms, including MUPS.

The use of PPIs in young children has its own specific history, indications, limitations and prospects. The production of acid by the gastric mucosa begins in a child from the first days of life.

The causes of gastroesophageal reflux disease are the same in both adult patients and infants. And children of the first year of life suffer no less than adults from the irritating effect of acid when it gets on the mucous membrane of the esophagus [20]. Currently, there is experience with the use of both omeprazole and esomeprazole in children aged 1 year and older [21-23]. However, existing instructions for the use of PPIs limit the use of both omeprazole and esomeprazole to children under 12 years of age (due to the lack of data on the effectiveness and safety of use), and to children over 12 years of age for all indications except GERD [24]. However, given the accumulated experience with the use of these powerful and fairly safe drugs, clinical studies of a new form of PPI in the form of sachets, specially designed for young children, are ongoing. The first results of these studies prove the good tolerability, safety and high effectiveness of this form for the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease in young children [22,23].

Thus, gastroesophageal reflux and gastroesophageal reflux disease are a widespread pathology already in childhood. Knowledge of the features of the clinical course of this disease in children in different age groups allows for timely diagnosis and early prescribing of adequate therapy. The complex use of medications in combination with the normalization of physical and neuropsychic stress can significantly reduce the number of esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease and reduce the development of complications arising from this pathology in children.

Literature 1. Health of children in Russia./edited by A.A. Baranov.// M.-1999.- P.66-92. 2. A.A. Baranov Scientific and organizational priorities in pediatric gastroenterology. // J. Pediatrics. - 2002. - No. 3. — P. 12-18. 3. Shcherbakov P.L. Lesions of the upper digestive tract in children (clinical and endoscopic studies) - Dissertation... Doctor of Medical Sciences. -M. 1997.- 275.p. 4. McColl KE Helicobacter pylori and acid secretion: where are we now? [comment]Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol, -1997-9(4)-P.333-5 5. Hurlimann S; DЁur S; Schwab P et al.//Effects of Helicobacter pylori on gastritis, pentagastrin-stimulated gastric acid secretion, and meal-stimulated plasma gastrin release in the absence of peptic ulcer disease. Am J Gastroenterol, - 1998 -93(8)-P.1277-85 6. Koster ED Adverse events of HP eradication: long-term negative consequences of HP eradication. Acta Gastroenterol Belg,- 1998- 61(3) -P.350-1 7. Varanasi RV; Fantry GT; Wilson KT// Decreased prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in gastroesophageal reflux disease./Helicobacter, -1998-3(3)-P.188-94 8. Filin V.I. Esophagitis in children: Author's abstract. dis... doc. honey. Sciences.- M.- 1987.- 47 p. 9. Armstrong D., Benett JR, Blum AL et. Al.// The endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology, 1996-111(1)- P.85-92 10. Khavkin A.I., Privorotsky V.F. / Modern ideas about gastroesophageal reflux in children. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in children.//in the book. "Act. Problems of abdominal pathology in children” / M. - 1999- P.48-57. 11. Reuben M; Rising L; Prinz C; Hersey S; Sachs G./ Cloning and expression of the rabbit gastric CCK-A receptor./ Biochim Biophys Acta.-1994.- 18.-V.1219(2).-P.321-7 12. Merki HS; Wilder-Smith CH; Walt RP; Halter F. //The cephalic and gastric phases of gastric secretion during H2-antagonist treatment. /Gastroenterology, 1991. - V. 101(3). - P.599-606. 13. Hurlimann S; Abbuhl B; Inauen W; Halter F./Comparison of acid inhibition by either oral high-dose ranitidine or omeprazole.// Aliment Pharmacol Ther.-1994.- V. 8(2).- P.193-201 14. Alliet P; Raes M; Brunel E; Gillis P./Omeprazole in infants with cimetidine-resistant peptic esophagitis. // J. Pediatr.-1998.- Feb.-V.132(2).-P.352-4. 15. Rational pharmacotherapy of diseases of the digestive system: A guide for practitioners; Under the general editorship of V.T. Ivashkina. - Moscow: Publishing House "Litterra", 2003. - 1046 p. 16. Lapina O.D. Mechanism of action of proton pump inhibitors. — Ross. magazine gastroenterol. hepatol. coloproctol., 2002, 2, 38-44. 17. Sach G, Shin JM, Besanson M et al. The continuing development of proton pump inhibitors with particular reference to pantoprazole. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 1995;9:363-78. 18. Blaser MJ Ecology of Helicobacter pylori in the Human Stomach // J. Clin. Invest. Am Society for Clinical Investigation Volume 300, Number 4, August 1997, 759-762 19. De Giacomo C; Bawa P; Franceschi M et al./Omeprazole for severe reflux esophagitis in children // J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr.-1997.-May.- V.24(5).-P.528-32 20. Shcherbakov P.L., Yatsyk G. .IN. Turti T.V. // Helicobacter pylori contamination of the gastrointestinal tract of newborn children / Current issues of infectious pathology in children.-M.-2003.-P. 223 21. Zhao J, Li J, Hamer-Maansson JE, Andersson T, Fulmer R, Illueca M et al. Pharmacokinetic properties of esomeprazole in children aged 1-11 years with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a randomized, open-label study. Clin Ther 2006;11:1868-76. 22. Tolia V, Youssef N, Belknap W, Gilger M, Traxler B, Illueca M. Treatment of erosive esophagitis with esomeprazole in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:E20 (Abs 22). 23. Gilger M, Tolia V, Vandenplas Y, Youssef N, Traxler B, Illueca M. Safety and tolerability of esomeprazole in children with gastroesophageal reflux disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;43:E20 (Abs 23). 24. Instructions for medical use of the drug "Nexium", reg. No. 013775/01 - 2006

There are few clear statistics on the prognosis of GERD in children.

There are many studies, but they are very heterogeneous in their approaches to defining the disease itself, evaluating treatments and assessing outcomes.

The most recent such attempt was the 2017 systematic review Variations in Definitions and Outcome Measures in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review.

For now, we can take it for granted that in some children, signs of GERD may persist for several years and even continue into adulthood.

There is a small group of children in whom one can immediately assume a more severe and prolonged course of GERD. They have risk factors, which I will talk about.

If there are no obvious risk factors, then any prognosis will be too uncertain.

I prefer to think optimistically that the chances of children outgrowing GERD on their own or with the help of doctors are quite high, and this is what I voice to parents.

Symptoms of esophagitis in children

The clinical picture of the acute form depends on the degree of the inflammatory process. The catarrhal type of esophagitis is not accompanied by any symptoms. When deeper layers are affected, the most common manifestations of the disease are painful swallowing and discomfort when eating hot or cold food. In the severe stage, the symptoms of reflux esophagitis in children are:

- burning pain behind the sternum;

- mild or sharp pain when swallowing;

- dysphagia;

- constant heartburn;

- excessive salivation.

After a few days, the symptoms of esophagitis in children may become less intense. However, after a couple of weeks, the sick child develops rough scars on the walls of the esophagus, leading to the development of stenosis. This condition is fraught with progression of dysphagia and food regurgitation. Therefore, at the first symptoms of the disease, you should contact a specialized clinic for a complete diagnosis of the stomach and intestines.

The chronic form of reflux esophagitis in children manifests itself:

- frequent heartburn, which becomes more intense when taking fatty and spicy foods, carbonated drinks;

- the appearance of belching;

- heavy breathing during sleep.

A child suffering from chronic esophagitis is predisposed to frequent pneumonia and the appearance of bronchial asthma. Babies under 1 year of age suffer from frequent regurgitation immediately after feeding. One of the symptoms of reflux esophagitis in children is malnutrition (lack of body weight in relation to its length).

To understand why we don’t like GERD, let’s discuss the definition of the disease.

Reflux disease differs from ordinary physiological reflux in two fundamental ways - it causes symptoms that interfere with normal life and it causes complications.

Complications can be directly related to damage to the esophageal mucosa and extra-esophageal ones.

I have already talked about extra-esophageal manifestations from time to time - they can affect the respiratory system and oral cavity.

What happens to the mucous membranes of the esophagus?

The most common option is the non-erosive form of GERD . During gastroscopy, the endoscopist sees swelling and redness, although it must be admitted that these signs are quite subjective.

A more severe manifestation is the appearance of erosions of the esophageal mucosa .

If non-erosive GERD can be compared to abrasion on the skin, then erosive esophagitis is real abrasions, that is, a deeper and longer-healing damage.

Detection of erosions indicates more severe reflux and often erosions are found again and again after stopping treatment.

Sometimes repeated erosions cause anemia - chronic anemia due to small but frequent bleeding from erosions.

In rare cases, the damage is so severe that ulcers .

There is a small chance that repeated damage will cause scarring and narrowing (stricture) of the esophagus.

With a stricture, difficulties arise when swallowing, first denser and then liquid food.

Another group that is very popular among pediatricians is antacids.

These include Phosphalugel, Almagel, Maalox and many others.

These drugs immediately bind acid on the mucous membranes of the esophagus and stomach. The contact time of the acid with the mucous membranes is reduced - this is the main bonus.

They also quickly reduce dyspeptic complaints - heartburn, burning in the epigastrium, this is an additional bonus.

But the main disadvantage of antacids is the short duration of the effect: they leave the stomach very quickly.

This is why antacids are not usually used for the chronic treatment of GERD.

Only one-time or short courses.

They are good as quick help for a child with dyspepsia.

Unlike anti-acid drugs, antacids can fight alkaline reflux - they bind bile, which can also be aggressive for the mucous membranes of the esophagus.

There are few statistics on this, but in cases of alkaline reflux, antacids are very popular.

Close relatives of antacids are alginates (Gaviscon), which also protect mucous membranes from acid.

They create “foam” on the surface of the stomach contents, which prevents gastric juice from exiting into the esophagus.

The main problem with alginates is the same as with antacids - the effect is short-lived and, accordingly, the need for repeated use throughout the day.

Alginates can be taken once for heartburn, but they can be prescribed by a doctor for short courses.

To summarize: antacids and alginates can be useful for the treatment of GERD in children and adults, but they do not play a primary role.

Sometimes it is useful to speed up the passage of food through the stomach to enhance treatment. Fullness of the stomach increases the pressure inside it and promotes reflux into the esophagus.

In this case a prokinetic agent ; I recently dedicated an entire post to this group.

And now an important question...

If the main culprit of reflux disease is the valve between the stomach and the esophagus, which, instead of letting everything into the stomach from above and not letting it back out, too often opens for no reason and releases something aggressive from the stomach into the esophagus, then why not treat this valve?

How can you act directly on this valve?

The first option is surgery to strengthen this valve.

But there are some subtleties here, which will be discussed separately.

The second option is drugs.

The most well-known complication of GERD among patients is Barrett's esophagus.

This is a condition in which the cells in the lining of the lower esophagus change and can then become cancerous. Conversion to cancer occurs quite rarely even in adults, but nevertheless, patients with Barrett's syndrome require regular and careful monitoring.

Barrett's esophagus is not a pediatric condition, as it requires a long history of GERD.

https://www.mayoclinic.org

In addition to GERD, chemical burns of the esophagus and chemotherapy may predispose children to this complication.

In my practice, I have only seen Barrett's esophagus a few times and these were teenagers.

Can a doctor assume a higher likelihood of long-term and severe GERD in a child?

Of course, based on the presence of risk factors.....

Causes of esophagitis in children

In the acute form, the esophageal mucosa most often becomes inflamed due to a damaging factor that acts for a short time. Pathology can lead to:

- acute viral infections that caused complications;

- mechanical impact and other damage;

- thermal and chemical burns caused by eating hot and spicy foods;

- allergic foods, when taken, the child’s body gives an immediate reaction. For this reason, it is extremely important to exclude from his diet foods to which the baby is allergic.

In the chronic form, the causes of esophagitis in children are:

- abuse of very hot, spicy foods;

- dysfunction of the stomach;

- allergic reactions;

- metabolic disorders - hypovitaminosis, elemental deficiency;

- tissue hypoxia;

- long-term intoxication.

Reflux esophagitis in children appears due to a functional disorder of the lower esophageal sphincter and shortening of the organ.

Risk factors for severe GERD:

- serious neurological impairment

- obesity

- condition after esophageal atresia

- diaphragmatic hernia

- achalasia of the esophagus

- prematurity

- cystic fibrosis

- bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- condition after lung transplant

Children with risk factors require more careful monitoring by a gastroenterologist and they are more likely to require surgical treatment of GERD.

There will be a separate discussion about treatment.

The photo of Rusty [email protected]

1, total, today