There are contraindications. Specialist consultation is required.

A diaphragmatic hernia is a congenital or acquired defect of the diaphragm, that is, a hernial opening through which abdominal organs move into the chest - the stomach, intestinal loops, spleen, part of the liver.

Causes of hernia

- Trauma – penetrating wounds of the abdomen or chest, blows.

- Underdevelopment of the diaphragm during embryonic development.

- Increased intra-abdominal pressure - dry cough, constant constipation, frequent childbirth, multiple pregnancies.

- Old age - the tone of the diaphragm changes after 60 years.

- Chronic gastrointestinal diseases - pancreatitis, peptic ulcer, esophagitis.

- Incorrect innervation of the diaphragm.

Depending on the cause of occurrence, diaphragmatic hernias are classified into three types:

- congenital;

- neuropathic;

- traumatic.

Causes of development of hiatal hernia disease

The esophagus has the shape of an elastic tube and consists of several layers (mucous, muscular and serous membranes). It is located mostly in the chest cavity. Passing between the lungs, large blood vessels and the heart, the esophagus enters the abdominal cavity through the esophageal hiatus in the diaphragm. The chest and abdominal cavities are separated from each other by a muscular horizontal septum (diaphragm), through which the esophagus passes. The normal dimensions of the opening in the diaphragm correspond exactly to the diameter of the passing esophagus, no more and no less. When the diameter of the hole changes, problems begin, one of which is called a hernia in the esophagus.

This phenomenon is quite common, but at small sizes it does not cause any particular problems and can only be noticed during a targeted examination. Medium and large hernias lead to the reflux of aggressive gastric juice into the esophagus and the appearance of clinical symptoms.

The most common causes of acquired hiatal hernia:

- Consequences of injuries to the thoracic and abdominal organs;

- Constant increase in intra-abdominal pressure, due to ascites (fluid in the abdominal cavity); with multiple or repeat pregnancies, chronic constipation, intense physical activity, due to frequent persistent cough (for example, with COPD - chronic obstructive pulmonary disease);

- Age-related decrease in tone (weakening) of the esophageal ligaments (the condition is more common in patients over 50 years old);

- Significant, sharp weight loss, disappearance of adipose tissue under the diaphragm;

- Previous operations on the esophagus;

- Obesity;

- Poor physical shape and tone of the diaphragmatic ligaments;

- Disturbances in the passage of food through the esophagus (esophageal motility disorders);

- Chronic diseases of the stomach, gall bladder, small intestine, leading to disruption of their motility (a situation where the normal contraction of organs and the process of passing food through them is disrupted) - often peptic ulcer of the stomach and duodenum, cholecystitis, pancreatitis.

Congenital hiatal hernia occurs in children with too short an esophagus, when the stomach (or part of it) is located abnormally high (in the chest cavity) due to insufficient length of the esophageal tube.

Symptoms

Small hernias of the diaphragm may not produce symptoms for a long time and are detected by chance during an examination of another organ. Large hernial sacs containing internal organs usually have a fairly clear clinical picture.

Symptoms in newborns:

- sleep disturbance, irritability;

- shortness of breath after eating;

- vomiting, frequent regurgitation;

- blue skin.

Symptoms in adults:

- belching air;

- bloating;

- pain behind the sternum due to the fact that the gastrointestinal tract is compressed in the hernial sac;

- heartburn after eating, when bending forward;

- difficulty breathing because the mediastinum and lung are shifted to the healthy side.

If the disease proceeds with complications, then bleeding begins from the hernial sac, and the mucous membrane of the esophagus becomes inflamed. It is life-threatening when the stomach or intestines are strangulated. In this case, the patient feels severe pain in the chest, vomits, stool retention is observed, and the general condition worsens. If medical assistance is not provided in time, peritonitis will begin, often leading to death.

A hiatal hernia (HH) is a condition caused by the displacement of abdominal organs into the mediastinum through the hiatus of the diaphragm.

It is assumed that hiatal hernias occupy one of the first places in the structure of diseases of the digestive organs, although their true prevalence cannot be assessed due to the often asymptomatic course and subjectivity of diagnostic criteria. This results in very large differences in estimates of the prevalence of hiatal hernias. For example, in the USA, in different studies they vary from 10 to 80% [1], but, as a rule, they correlate with obesity and age.

Although most cases of hiatal hernia remain asymptomatic and are diagnosed incidentally, they are often associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), since incompetence of the lower esophageal sphincter can be a consequence of hiatus. Paraesophageal hernias with clinical manifestations can progress and cause serious complications such as reflux esophagitis, peptic ulcer of the esophagus, perforation and stricture of the esophagus, esophageal bleeding, strangulated hernia. Detection and treatment of asymptomatic hiatal hernias are not indicated, but if clinical manifestations of the disease develop, they require examination and possible surgical intervention.

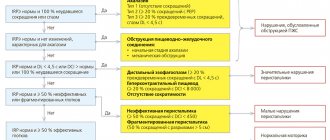

The American Association of Gastroenterological and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) guidelines for the treatment of hiatal hernias published in 2013 [2] provide a classification that includes 4 types of hiatus hernias.

Type I hernias are sliding hernias, in which the esophagogastric junction is displaced above the diaphragm [3], but the stomach maintains its normal longitudinal position [4], and its bottom remains below the esophagogastric junction. Type I hiatal hernia is characterized by weakness and elongation of the esophageal-phrenic ligament, which plays an important role in maintaining the normal intra-abdominal position of the esophagogastric junction. This laxity of the ligamentous apparatus leads to varying degrees of migration of the esophagogastric junction through the dilated diaphragmatic opening.

Type II hernias are true paraesophageal hernias (PEG), in which the esophagogastric junction remains in its normal anatomical position, but part of the gastric fundus is displaced through the diaphragmatic opening up along the esophagus.

Type III hernias are a combination of types I and II, when both the esophagogastric junction and the fundus of the stomach are displaced upward through the diaphragmatic opening. In this case, the fundus of the stomach is located above the esophagogastric junction.

Type IV hernias are characterized by the presence of other abdominal organs, such as the omentum, colon, small intestine, or spleen, in the hernial sac rather than the stomach.

More than 95% of hernias are type I. As a group, types II–IV are PEG and differ from type I hernias in the relative preservation of the posterolateral esophageal-diaphragmatic ligaments around the esophagogastric junction [5]. Among PEGs, more than 90% are type III, and the least common is type II [6].

The term “giant paraesophageal hernia” is often used in the literature, although there is no generally accepted definition. Some authors suggest that all hernias of types III and IV be considered giant PEG [9], but most researchers classify it as PEG, in which from 1/3 to ½ of the stomach is located in the mediastinum [7–10].

The cause of the development of hiatal hernia is considered to be weakness of the esophageal-diaphragmatic ligament of Laimer and expansion of the crura of the diaphragm [11]. Weakening of the esophageal-diaphragmatic ligament occurs as a result of its stretching due to a decrease in the content of elastin fibers [12]. In most cases, hiatal hernias are acquired, although in a very small number of cases multifactorial familial inheritance may play a role [13].

Surgical treatment of hiatal hernia

Indications for surgical treatment

I hiatal hernia .

The main clinical significance of type I hiatal hernias lies in their relationship with GERD, in which antireflux surgery is one of the treatment methods, regardless of the presence or absence of hiatal hernia. Therefore, surgical interventions for type I hiatal hernia in combination with GERD must necessarily include fundoplication [14] as an antireflux procedure.

In the absence of GERD, sliding hernias do not cause any consequences, although there are isolated reports of complications associated with them [15–17]. In rare cases, dysphagia or gastric ulcers may occur with type I hiatal hernia, but, as a rule, in the absence of GERD, they do not require surgical treatment [18].

Paraesophageal hernias.

Completely asymptomatic PEGs are very rare and, as a rule, are not accompanied by clinical manifestations. [8]. Typically, symptoms are mild, so PEGs are most often discovered incidentally on a chest x-ray performed for another reason [20, 21].

Careful questioning of patients with PEG may reveal symptoms such as chest tightness or difficulty breathing after eating. Symptoms of reflux with PEG are rare. It is likely that some PEGs develop from small hiatal hernias. Others may result from anatomical changes in the spine, such as kyphosis and degenerative intervertebral disc disease [22].

As more and more of the stomach moves into the chest cavity, it causes compression of the lungs and a reduction in their vital capacity, as a result of which respiratory disorders begin to predominate in the clinical picture [8, 23]. In addition, PEGs may be accompanied by recurrent aspiration pneumonia [21]. Later, as a result of strangulation, ischemia of the gastric mucosa develops, causing ulceration, bleeding and anemia. 50% of patients with PEG have iron deficiency anemia [23].

Obstructive symptoms range from mild nausea, bloating, or fullness after eating to dysphagia and vomiting. The pain is often described as a feeling of heaviness in the epigastrium or abdominal pain after eating, which is often relieved by vomiting.

The natural history of hiatal hernia remains insufficiently studied. From the few available data, it follows that the risk of developing acute conditions, especially obstruction, is associated only with hernias in which the fundus of the stomach has migrated above the diaphragm, i.e. with PEG. The risk of progression from asymptomatic to clinically manifested PEG is estimated to be approximately 14% per year [24, 25].

Therefore, and given the high mortality associated with these complications, in particular gastric necrosis, it was generally accepted that all PEGs require elective surgical treatment [46, 47]. This is especially important for clinically manifested hernias, which are accompanied by a higher risk of complications [26]. However, age should not be considered as a contraindication to surgery [27].

However, more recent studies have shown that mortality after emergency surgery for complications of PEG is significantly lower than previously estimated (5.4% versus 17%) [25, 28]. In addition, the risk of developing emergency conditions requiring emergency surgery does not exceed 2% per year [29–32].

Analysis of modern studies allows us to conclude that surgical treatment of completely asymptomatic PEGs is not necessary. In these cases, expectant management is a safe alternative to surgical interventions, which should be used mainly in patients with symptoms of obstruction, severe and complicated by GERD, anemia and signs of gastric incarceration [29–33].

Additionally, an analysis of these studies found that elective laparoscopic procedures for asymptomatic PEGs may actually reduce quality-adjusted life expectancy (QALE) in patients aged 65 years and older.

Incarceration, bending or torsion of the stomach in the hernial sac during PEG can lead to ischemic damage, necrosis and perforation. When these complications develop, surgical intervention with gastric ablation and partial resection in case of necrosis is required.

Thus, taking into account the above, indications for surgical treatment of hiatal hernia should be based on the following recommendations.

— Surgical treatment of type I hiatal hernia in the absence of GERD is not indicated.

― The indication for surgery for type I hiatal hernia is severe or complicated GERD that is not amenable to conservative therapy. Fundoplication is mandatory for surgical treatment of GERD.

- All symptomatic PEGs require surgical treatment, especially if acute obstruction or strangulation develops.

— Surgical treatment of completely asymptomatic PEGs is not always indicated. When considering the indications for intervention for asymptomatic PEG, patient age and comorbidities should be taken into account.

— Acute volvulus and strangulation of the stomach in the hernial sac with PEG require straightening of the stomach and, if necessary, partial resection.

Laparoscopic and open surgeries

Surgical interventions to eliminate hiatal hernia usually include 4 stages: excision and resection of the hernial sac, mobilization of the esophagus, plastic surgery of the crura of the diaphragm, and fundoplication [34–36]. These operations can be performed using either open (abdominal or thoracic) or laparoscopic approaches.

Although laparoscopic operations are becoming increasingly popular, surgical treatment of hiatal hernia using an open approach still remains predominant. The results of an analysis of almost 38 thousand surgical interventions for hiatal hernia performed in the United States from 1999 to 2008 indicate that 91% of operations were open (74.4% with abdominal and 17% thoracic access). Laparoscopic operations accounted for only 9% [37].

Postoperative mortality was 1.1% and did not depend on the type of surgical approach, but for laparoscopic operations the length of hospital stay was the shortest (4.5 days versus 7.8 days for transthoracic operations). A review of the literature [38] also showed that although there are no randomized trials comparing laparoscopic and open surgery for hiatal hernias, laparoscopic procedures are associated with fewer complications such as pneumonia, thrombosis, hemorrhage, urinary tract infections and wound infections. In addition, small incisions during minimally invasive interventions reduce the risk of postoperative hernias [39].

Several reports of laparoscopic surgery for giant PEGs have also shown excellent results [40].

At the same time, the higher recurrence rate after laparoscopic correction of the hiatal hernia caused some concern. In a study of 60 PEG operations [41], the recurrence rate after laparoscopic procedures was 44% compared with 23% after open procedures, although this difference was not statistically significant.

Another study reported that in the initial stages of implementation of laparoscopic correction of the hiatal hernia, the recurrence rate reached 44% compared with 15% after open surgery, but as experience gained, it decreased to the level observed after open surgery [42].

In addition, there is evidence that relapses after laparoscopic operations are most often clinically insignificant or asymptomatic and are usually associated with the presence of a short esophagus or tension in the crura of the diaphragm during their plastic surgery [43].

Conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery is sometimes necessary for reasons such as bleeding, splenic injury, or the presence of dense adhesions. Therefore, it is important that surgeons performing laparoscopic correction of the hiatal hernia have sufficient skills and experience in performing open surgery.

According to the SAGES recommendations for the treatment of hiatal hernias [2], in most cases of hiatal hernias requiring surgical treatment, the laparoscopic method of their correction is preferable, since it is accompanied by fewer postoperative complications and shorter hospital stays compared to open operations.

Transthoracic and transabdominal operations

Currently, there is no data on controlled randomized studies directly comparing the results of surgical treatment of hiatal hernia using transthoracic and transabdominal approaches. In addition, there are no data evaluating minimally invasive transthoracic interventions. Although transthoracic access provides excellent visualization of the esophageal hiatus and allows maximum mobilization of the esophagus, this method is used less and less due to the more severe course of the postoperative period, more complications and longer hospital stay. However, one of the advantages of the transthoracic approach is the possibility of wider mobilization of the esophagus [44].

Open transabdominal surgery is the method of choice for emergency surgery due to complications of the hiatal hernia, when there is peritoneal contamination or gastric necrosis [45].

A. Geha et al. [46] reported the results of surgical treatment of 100 patients with giant hiatal hernias. In 2 of 18 patients operated on using a transthoracic approach, repeated open transabdominal intervention was required due to the development of torsion of the stomach around its axis. The remaining 82 patients were operated on using an open transabdominal approach. All these patients underwent plasty of the esophageal opening of the diaphragm, fundoplication was performed in 32 patients, 2 patients required Collis gastroplasty to increase the length of the esophagus. There were no relapses in the entire cohort.

Other modern authors who compared transabdominal and transthoracic approaches for surgical treatment of PEG concluded that their results were equivalent [47].

Antireflux procedures

Fundoplication is a standard component of surgical methods for correcting the hiatal hernia. The essence of Nissen fundoplication is to form a circular cuff from the upper part of the fundus of the stomach around the lower part of the esophagus in order to increase pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter to prevent reflux.

In 1973, the results of a 20-year retrospective study of surgical treatment of 95 patients with PEG without fundoplication were published, in which the rate of radiologically confirmed recurrence was 33% [48]. This was the basis for considering fundoplication as a necessary component of surgical treatment for PEG.

In 2011, a study was published that compared the results of treatment with PEG with fundoplication ( n

=35) and without it (

n

=25) [49]. Fundoplication has been used in patients with GERD. Among 25 patients who did not undergo fundoplication, 28% developed esophagitis after surgery, and 39% had abnormal reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus. The authors concluded that fundoplication should be a routine part of PEG correction surgery. A study of the results of surgical interventions using fundoplication in 4 patients with type II hiatal hernia and 11 patients with type III hiatal hernia showed that 1 year after surgery, all patients were free of symptoms, dysphagia, or reflux. The authors suggested that fundoplication restores the function of the lower esophageal sphincter and prevents reflux in the postoperative period. In addition, fundoplication secures the stomach under the diaphragm, preventing recurrence of hernias [50].

SAGES recommendations for the treatment of hiatal hernias [2] stipulate the need for fundoplication in the surgical treatment of both sliding hernias and PEG.

Gastropexy

According to SAGES guidelines for the treatment of hiatal hernias [2], gastropexy can be used in addition to hiatal hernia repair as an additional measure to keep the cardia below the diaphragm to prevent relapses. Insertion of a gastrostomy tube in these cases may ease the postoperative period in some patients.

Surgical repair of the hernia with gastropexy alone without hiatal reinforcement is a safe alternative in patients at high surgical risk, but may be associated with more frequent recurrences. Standard plastic surgery is preferred.

One of the first studies of the use of gastoropexy to reduce recurrence rates after laparoscopic operations for hiatal hernia examined the results of treatment of 28 patients who underwent gastropexy in addition to removal of the hernia and hernial sac, cruroplasty and fundoplication [51]. Patients with type I hernias were not included in the study. When assessing the results, it was found that no relapse occurred within 2 years after the operation.

Similar results were obtained in another study that included 89 patients who underwent laparoscopic correction of large hiatal hernias. It has also been shown that the addition of gastropexy to hernia repair significantly reduces the recurrence rate [52].

At the same time, in a similar study of the use of gastropexy in addition to laparoscopic interventions for PEG in 116 patients, no significant difference in the relapse rate was found [53].

Gastrostomy tube placement for decompression and enteral nutrition/drug administration was studied in a retrospective study of intrathoracic hiatal hernia in 73 patients. In 60% of this series, a gastrostomy tube was inserted during surgery and was required postoperatively for decompression and/or drug administration [54].

Some authors have described hernia reduction and gastropexy without crurorrhaphy and removal of the hernial sac, particularly in patients with severe symptoms [55, 56]. Mortality and complication rates were low, but after 3 months, radiographic recurrence was detected in 22% of patients. The results of this approach are inferior to standard surgical techniques for correcting the hiatal hernia, and therefore isolated gastropexy should be considered as a simplified backup option in patients with high surgical risk.

Removal of the hernial sac

The SAGES guidelines for the treatment of hernias [2] suggest that during surgery for PEG, the hernial sac should be separated from the mediastinal structures and then removed. If the hernial sac cannot be completely removed, it must be removed at least partially so that no excess mass remains during fundoplication.

It is assumed that removal of the hernial sac during surgical correction of PEG allows mobilization of the esophagus, facilitates the reduction of hernial contents into the abdominal cavity and reduces the risk of early recurrence, and also protects the esophagus from iatrogenic damage [57, 58].

Observations supporting removal of the hernial sac [59] are limited to a small number of patients with different types of hiatal hernias and different surgical techniques. In this study, over a 38-month follow-up period, relapse developed in 5 of 25 cases of interventions without removal of the hernia sac, all from 1 to 8 weeks after surgery. At the same time, in 30 patients in whom the operation included removal of the hernial sac, not a single relapse occurred within 15 months after the operation.

Sometimes removing the hernia sac can be quite difficult, especially with large hernias. In particular, in the presence of such difficulties, excision of the hernial sac increases the risk of injury to the vagus nerve. According to experts, in such a situation one can limit oneself to isolating the hernial sac and separating it from the legs of the diaphragm, but its complete removal is not necessary [58, 60].

A retrospective study with a small number of cases comparing this approach with complete excision of the hernia sac showed a trend towards more frequent recurrences with incomplete excision of the hernia sac, but there were no statistically significant differences between the groups [61].

Some researchers believe that the currently available evidence is insufficient to draw conclusions about the effect of hernial sac removal on the outcome of surgical treatment of the hernia, and that it is premature to make recommendations for its removal [62].

Application of implants

For many years, the main method of strengthening the hernial orifice when closing a hernia defect was hiatal repair by suturing the crura of the diaphragm (anterior and posterior crurorrhaphy). After these operations, the recurrence rate reached 42% with an open approach and was even higher with laparoscopic interventions [63, 64].

The main reason for the development of recurrent hiatal hernia after crurorrhaphy with a large size of the esophageal opening is the divergence of the legs of the diaphragm as a result of the cutting of sutures due to excessive tension during their suturing, as well as hypotrophy or fibrous degeneration of the muscular legs of the diaphragm [65, 66].

This prompted many authors to search for new ways to strengthen the esophageal opening of the diaphragm. Although some methods have been developed for plasty of the hiatus with the patient's own tissues, such as the round ligament of the liver [67] or the left lobe of the liver [68], the use of plasty with various implants (prostheses, patches) for this purpose has become more widespread.

Both synthetic fabrics (polyester, polypropylene, polytetrafluoroethylene - PTFE) and biomaterials - the submucosal layer of the small intestine (SIS), acellular allograft from human dermis (AHD), etc. are used as materials for the manufacture of implants [69, 70].

Currently, the most common type of patch used in hiatal hernia surgery is absorbable mesh implants (Vicryl) [71].

The optimal prosthetic technique and the ideal type of mesh implant remain unknown at this time. Most often, the mesh is used as an overlay after the primary suturing of the legs of the diaphragm. In addition, crurorrhaphy has found application using Teflon pads under the sutures when suturing the legs of the diaphragm to prevent their eruption [72]. If it is impossible to approximate and suture the legs of the diaphragm, implants are used as an insert or bridge [73].

Several relatively large studies evaluating the results of mesh implants have been published in recent years, but they have not brought complete clarity to the problems associated with their use.

In a recently published meta-analysis by J. Huddy et al. [74], which combined 9 studies, compared the results of 3 methods of laparoscopic correction of the hiatal hernia: crurorrhaphy ( n

=310), plastic surgery with implants made of synthetic materials (

n

=214) and biomaterials (

n

=152).

According to the results of the meta-analysis, there were no differences in the incidence of complications after crurorrhaphy and plastic surgery with implants of both types.

The overall relapse rate after plastic surgery with both types of implants was statistically significantly lower than with crurorrhaphy: 14.5% versus 24.5%; odds ratio (OR) 0.36 (95% confidence interval - CI 0.17–0.77; p

=0.009).

In addition, after the use of synthetic meshes, relapses occurred less frequently than after implants made of biomaterials: 12.6% versus 17.1%; OR 0.30 (95% CI 0.12–0.73; p

= 0.008). A survey of 503 surgeons conducted as part of this meta-analysis showed that their preferences in choosing a method of plastic surgery for correction of the hiatal hernia and surgical technique varied significantly.

The authors of the meta-analysis concluded that, compared with crurorrhaphy, the use of both synthetic materials and bioprostheses reduces the relapse rate, but synthetic implants are more effective than bioprostheses. There is insufficient data to determine the optimal surgical technique.

Another meta-analysis, including 13 studies, compared the results of laparoscopic surgery for large hiatal hernias (1194 patients, 521 with crurorrhaphy and 673 with mesh implants). The majority of studies included in the meta-analysis reported significant symptomatic improvement. The use of mesh implants was associated with fewer relapses (OR 0.51; 95% CI 0.30–0.87; p

=0.014), but the differences in the need for re-interventions were statistically insignificant (OR 0.42; 95% CI 0.13-1.37;

p

=0.15). The authors concluded that there was insufficient evidence to support mesh implants.

Finally, a randomized controlled trial (RCT) conducted by D. Watson et al. [75], showed that crurorrhaphy and plastic surgery with mesh implants for large hiatal hernias give the same results.

This multicenter, prospective, double-blind RCT compared 3 methods of hiatal repair: crurorrhaphy ( n

=43), plastic with absorbable mesh (

n

=41) and non-absorbable mesh (

n

=42). The primary clinical outcome studied was hernia recurrence in the first 6 months after surgery. The secondary outcome studied were clinical indicators (belching, heartburn, odynophagia, etc.) 1, 3, 6 and 12 months after surgery.

Recurrent hernias after crurorrhaphy, absorbable mesh, and nonabsorbable mesh repair were identified in 23.1, 30.8, and 12.8% of patients, respectively ( p

=0.161). Differences in clinical parameters were minor.

Thus, in this RCT, there were no significant differences in the results of using these methods of closing the hernia defect in hernia, either in the frequency of recurrence of the hernia or in clinical indicators.

An important issue remains the limited data on the long-term safety of various types of mesh prostheses and their techniques, since most studies on this topic are small case series with a median follow-up period of less than 3 years. The literature describes complications of implants of all types, both synthetic and biological, as well as various configurations.

Although the most dangerous complication of synthetic implants is esophageal pressure ulcers, other complications may occur, such as the formation of coarse scar tissue around the esophagus with the development of stenosis, implant migration or effusion [76–80], and pericardial tamponade [81].

According to the conclusion of the authors of the SAGES recommendations for the treatment of hiatal hernias [2], the use of mesh implants to strengthen the hernial orifice during the surgical treatment of large hernias leads to a decrease in the frequency of relapses in the early postoperative period. However, the long-term consequences of their use have not yet been well studied, and therefore it is impossible to come to a definite recommendation for or against their use.

New endoscopic antireflux procedures

Endoscopic antireflux therapy (EART) is a relatively new concept in the treatment of GERD, including those with hiatal hernia. The application of EART is aimed at solving 3 key issues:

― treatment of refractory GERD, i.e. elimination of symptoms that cannot be fully controlled with drug therapy;

― discontinuation of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) in patients with drug-controlled GERD who want to stop taking them;

— minimizing the need for surgical treatment of hiatal hernia [82].

Currently, there are 2 types of endoscopic antireflux procedures for the treatment of GERD, which can be used in the treatment of small hiatal hernias:

— radiofrequency therapy of the esophagogastric junction using a Stretta catheter;

- transoral non-invasive fundoplication (TIF).

Radiofrequency therapy of the esophagogastric junction

Radiofrequency therapy of the esophagogastric junction using a Stretta catheter (Curon Medical, USA) has been used for quite a long time and has a significant evidence base [83, 84]. In the United States, Stretta was approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of GERD in 2000 (Figure 1.)

Rice. 1. Stretta catheter. a - general view; b - introduction, after inflating the balloon, of 4 needles into the muscular layer of the esophageal-gastric junction, followed by exposure to radiofrequency energy.

The essence of the method is the circular impact of a radiofrequency sensor on the area of the esophageal-gastric junction. The average duration of the procedure is 40–60 minutes [85].

Compared to surgical treatments for hiatal hernia, Stretta is a much less invasive outpatient procedure and has fewer side effects and complications, and does not require general anesthesia; Typically, only moderate sedation is used during this procedure.

The entire procedure lasts less than 40 minutes and does not require long-term observation after its completion. The next day, most patients resume their normal activities.

Side effects include minor throat and chest pain that may occur for a short period of time immediately after the procedure.

Experimental and clinical studies have found that radiofrequency exposure to the area of the lower esophageal sphincter helps to increase its tone and reduce the number of transient relaxations [86].

This method is most effective in patients without a hiatal hernia, and therefore the presence of a hiatal hernia greater than 2 cm is a contraindication for use. At the same time, there is evidence of positive results from using the method for hiatal hernias less than 2 cm.

In a randomized placebo-controlled study, D. Corley et al. [87] included 64 patients with GERD. Thirty-five of 64 patients received radiofrequency therapy using a Stretta catheter, and 29 received a sham procedure. In these groups, 14 (40%) and 12 (41%) patients, respectively, had a hiatal hernia greater than 2 cm. The primary clinical outcomes studied were changes in GERD symptoms and quality of life according to the GERD-HRQL (Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease - Health Related Quality of Life) questionnaire Scale).

6 months after treatment, the clinical manifestations of GERD decreased and the quality of life improved significantly and statistically significantly in patients from the active treatment group compared to patients in the sham intervention group.

More patients in the active treatment group than in the sham group had no daily heartburn ( n

=19 (61%) vs

n

=7 (33%);

p

= 0.05), and more had GERD-HRQL quality of life scores improved by more than 50% (

n

= 19 (61%) vs.

n

= 6 (30%);

p

= 0.03). These positive changes were maintained 12 months after treatment. At the same time, 6 months after treatment, no differences were found between the groups in the reduction in daily drug use and in the time of exposure to acid in the esophagus.

In another RCT [88], 36 patients with GERD were randomized into 3 groups. In groups A and C, 12 patients each received single and double radiofrequency therapy with a Stretta catheter, respectively. In group B, 12 patients underwent a simulation of this procedure. In these groups, 6 (50%), 7 (58%), and 9 (75%) patients, respectively, had a hiatal hernia less than 2 cm.

After 12 months, there was a significant improvement in GERD symptoms in both active treatment groups, while there was little change in the sham intervention group. In addition, in the active treatment groups, the quality of life according to the GERD-HRQL questionnaire improved to a greater extent, the use of PPIs, the time of exposure to esophageal acid during pH monitoring, and the severity of esophagitis decreased.

Transoral non-invasive fundoplication

Transoral (endoluminal) interventions to correct the hiatal hernia are being developed within the framework of the concept of endoscopic surgery through natural orifices (Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery - NOTES). Transoral methods of treating GERD and, in some cases, hiatal hernia include transoral non-invasive fundoplication (Transoral Incisionless Fundoplication - TIF). The main representatives of this new technology are the Esophyx systems (Endogastric Solutions, USA) and MUSE™ (Medigus, Israel), which are used for minimally invasive full-thickness fundoplication (Fig. 2)

Rice. 2. Esophyx system. a - general view; b) creation of a fundoplication cuff using Esophyx. [89]. Procedures using these methods are usually performed under general anesthesia and last approximately 1 hour.

In the United States, the Esophyx System was approved by the FDA for the treatment of GERD in 2007. With the Esophyx System, a full-thickness esophagogastric fundoplication cuff with a 270° envelopment of the esophagus with the gastric fundus is created using a special device integrated into the distal end of the endoscope. The formed cuff is fixed with longitudinal polypropylene sutures about 3.5 cm long.

Transoral fundoplication with the MUSE system is performed in a similar way, with the difference that it uses a Medigus Ultrasonic Surgical Endostapler built into the endoscope, and the fundoplication covers the esophagus only 180° along the anterior surface.

In properly selected patients, the use of transoral fundoplication leads to a sustainable reduction in the size of hernias and effective restoration of the antireflux mechanism of the esophagogastric junction.

The effectiveness of the Esophyx system was studied in a placebo-controlled RCT involving 44 patients with GERD who were randomized to receive transoral fundoplication ( n

=22) and in the group with sham use of Esophyx (

n

=22) [90]. Exclusion criteria were body mass index (BMI) >35 kg/m2, stage IV gastroesophageal leaflet valve (GEV) according to L. Hill’s classification and a hiatal hernia larger than 3 cm. 17 patients in each group had a hiatal hernia measuring no more than 3 cm. Primary The outcome studied was the rate of GERD remission 6 months after the intervention. Secondary outcomes were PPI use, esophageal acid exposure time during pH monitoring, GERD-HRQL quality of life, and resolution of reflux esophagitis.

6 months after the intervention, 13 (59%) patients from the active treatment group maintained clinical remission without the use of PPIs, while in the sham treatment group, remission was achieved in only 4 (18%) patients. All secondary outcomes were also in favor of transoral fundoplication.

Based on the data obtained, the authors of the RCT concluded that ideal candidates for transoral fundoplication are patients with persistent symptoms of GERD and with the following anatomical characteristics:

— hiatal hernia <2 cm without dilatation of the diaphragmatic opening;

- normal mobility of the esophagus;

- deviations in the results of long-term pH measurements or the presence of reflux esophagitis during endoscopy or biopsy;

― II–III degree of state of GESC p

Advantages of laparoscopic surgery for hiatal hernia

- Thanks to visualization of the surgical area, gentle surgery is possible.

- The image of all anatomical formations (gastric vessels, vagus nerve, fascial spaces) is displayed with multiple magnification on the monitor, which eliminates the risk of complications during the operation.

- Restoring the anatomy of the abdominal esophagus, diaphragmatic opening, stomach, and creating a functional valve allows a person to continue to lead a normal lifestyle - without medications and a strict diet.

- Natural protective reflexes are preserved, which is important for the quality of life in the future.

- Excellent cosmetic effect - traces from minimal incisions on the abdominal skin become invisible after healing.

- No blood loss, painless.

- Short recovery period - after 2-3 weeks you can return to work

- The number of relapses is kept to a minimum; this figure at SwissClinic does not exceed 2%.

Indications and contraindications

Indications

- large hernia;

- ineffectiveness of conservative therapy;

- risk of infringement;

- development of complications (esophagitis, bleeding, esophageal ulcer, anemia, etc.);

- dysplasia of the mucous membrane;

- narrowing of the esophagus, deformation of the stomach;

Contraindications

- infectious and inflammatory processes in acute form;

- severe concomitant diseases;

- some blood pathologies;

- oncological pathologies;

- pregnancy.

Doctor's comment

Have you been diagnosed with a hiatal hernia and are you interested in all the possible treatment options? In asymptomatic cases, conservative treatment aimed at preventing complications is possible. For you - a full-fledged or day hospital with comfortable wards. In case of complicated disease, the only treatment option is surgery. At SwissClinic we prefer gentle surgical methods. The methods of laparoscopic surgery for esophageal hernia allow you to radically get rid of the disease, and in the future you will be able to lead your usual lifestyle without the need to take medications or strictly adhere to a diet. Thanks to the improved technique used in the clinic, the risk of relapses after recovery is minimized. Our Center is equipped with the most innovative equipment, so all operations are painless, and the risk of complications is practically eliminated. To choose the most optimal treatment method, you need to undergo a thorough examination; all necessary diagnostic procedures can be performed with us - without tiring queues and in a short time! Each patient receives only an individual approach! To receive more detailed information about your upcoming treatment, make an appointment! We will select treatment tactics, taking into account the characteristics of your body!

Head of the surgical service at SwissClinic Konstantin Viktorovich Puchkov