Intestinal dyskinesia - symptoms, diagnosis, treatment and prevention

Details Author: LDC Neuron Published: November 10, 2015

Sometimes we say, we will never get sick with this, or, we live in a different environment and zone... but we are deeply mistaken, for this disease, namely for intestinal dyskinesia, there is neither distance nor barriers, and anyone can get sick with this insidious disease. But in this article we will look at both its symptoms and how to treat intestinal dyskinesia at home!

Accurate diagnosis

If a patient has symptoms of intestinal dyskinesia, you need to seek help from a gastroenterologist, who will prescribe the necessary examinations and tests, study the symptoms, and then make a diagnosis.

Since the clinical picture of intestinal dyskinesia is similar to other diseases, diagnosis is carried out by exclusion:

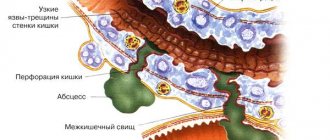

- At the first stage, the large intestine is examined for the presence of life-threatening pathological processes and formations (polyps, tumors, diverticula).

- Then a stool analysis is prescribed to identify blood or mucus impurities, as well as endoscopy and irrigoscopy.

If indicated, a biopsy of the affected tissue may be necessary.

Symptoms of intestinal dyskinesia

Intestinal dyskinesia is manifested by a number of negative “surprises”, which can differ significantly in symptoms from person to person. First of all, patients are annoyed by a variety of pain and bloating in the abdomen. It can be a cutting, aching, dull, boring pain that lasts from several minutes to several hours. It is difficult for the patient to say where exactly the pain manifests itself; he notes that such sensations appear “in the whole abdomen.” Painful sensations very often stop when a person falls asleep, and resume again after waking up. In some cases, rumbling in the stomach and bloating are practically the only signs of the disease. The occurrence of these symptoms does not depend on what food a person eats.

Causes of the disease

The appearance of primary spastic colitis is often caused by factors of a psychogenic nature:

- Experienced stress.

- Nervous tension, nervousness.

- Long-term depression.

- Negative emotional background around the patient.

The second most common causes of irritable bowel syndrome are those related to diet and diet, in particular, insufficient fiber intake.

In addition, primary dyskinesia develops due to the proliferation of pathogenic flora in the intestines or due to food poisoning.

Secondary colitis is provoked by:

- Diseases of the abdominal organs.

- Hormonal imbalances.

- Diabetes.

- Uncontrolled use of antibiotic drugs, psychotropic substances and anticonvulsants.

Diagnosis of intestinal dyskinesia in children

Well, the treatment itself, intestinal dyskinesia is successfully treated with the use of psychotropic drugs, such as tranquilizers, antipsychotics, antidepressants, plus psychotherapy sessions. Effective will be drugs that have a general strengthening effect on the central nervous system, which, in turn, helps to normalize the functioning of the autonomic nervous system and reduce the level of excitability of the intestinal muscles. In this case, the prescription of medications, as well as the choice of tactics for psychotherapeutic assistance, is carried out by a specialist of the appropriate profile. It is important to note that psychotropic drugs are not recommended for long-term use.

LDC "Neuron"

- < Back

- Forward >

Types of disease

Large intestinal dyskinesia is diagnosed in two types:

- Independent - primary spastic colitis - appears due to a disorder of intestinal motility.

- A disease that develops due to disruption of the functioning of other organs of the gastrointestinal tract or changes in hormonal levels is secondary colitis.

Hypermotor spastic dyskinesia

It is characterized by increased intestinal tone, which is accompanied by spasmodic contractions. The patient complains of loose stools, aggravated by colic, cramping and paroxysmal pain. There is a feeling of fullness in the intestines, gases collect in the stomach, and belching appears.

Hypomotor atonic dyskinesia

The disease is accompanied by a decrease in the motor function of the intestinal muscles and constant constipation. The accumulation of compacted feces causes bursting pain in the lower abdomen. Against this background, the patient’s well-being deteriorates. Appears:

- weakness;

- nausea;

- rectal polyps;

- haemorrhoids;

- anal fissures.

The patient becomes irritable with sudden mood swings.

Prevention

There is no specific prevention of intestinal dyskinesia, since the mechanism of its development is not clear.

Nonspecific prevention measures include:

- balanced diet;

- drinking enough liquid;

- rejection of bad habits;

- avoiding excessive physical and mental stress;

- rational work and rest schedule, a good night's sleep;

- sufficient physical activity;

- avoidance of irrational use of medications, refusal of self-medication.

Therapeutic diet

Patients suffering from intestinal dyskinesia should control their diet and take into account the following recommendations:

- Consume fresh, natural products (without dyes, preservatives, or flavor enhancers).

- Most of the diet is porridge (wheat, millet, buckwheat, oatmeal). The restriction applies only to rice cereals.

- Increase the consumption of fruits, vegetables, freshly squeezed juices (cabbage, beetroot, carrot, apple).

- Drink at least 2 liters of clean water per day.

- Process foods by boiling, baking or steaming.

- Avoid eating fatty meats and fish.

- Eat only fresh fermented milk products, otherwise the effect will be the opposite - constipation is possible.

- Reduce the amount of salt in prepared dishes.

- Eliminate pastries and sweets.

Portions should be small, and the number of meals per day should be 5–6 times. It is strictly not recommended to overeat.

A special diet is a prerequisite for the effectiveness of treatment of any disease associated with the digestive system. In this way, it is possible to achieve improved intestinal motility, reduce the likelihood of fecal accumulation, and prevent constipation.

Motility disorders of the digestive organs and general principles of their correction

Almost any disease of the digestive organs is accompanied by a violation of their motor function. In some cases they determine the nature of clinical manifestations, in others they hide in the background, but are almost always present. And this is natural, since the nature of motor activity is under control and in close connection with the state of the digestive organs, as well as under the control of nervous and humoral mechanisms of a higher level.

All conditions associated with impaired motility of the digestive organs can be divided into two large groups. In the first case, the disorders in question are associated with a pathological process in one or another part of the digestive system, for example, with duodenal ulcer or colitis. Motility can change when the intestine is compressed from the outside, there is an obstacle in its lumen, or the volume of its contents increases, as, for example, observed with osmotic diarrhea. In other cases, motor skills change due to a violation of its regulation by the nervous or endocrine systems. This group of diseases is called functional, which emphasizes the secondary nature and reversibility of developing changes. At the same time, long-term functional disorders of the motility of the digestive organs sooner or later lead to their “organic” damage. Thus, functional gastroesophageal reflux can cause reflux esophagitis, that is, lead to the formation of gastroesophageal reflux disease, and irritable bowel syndrome can lead to the development of chronic colitis. Thus, the favorable course of functional disorders, which is emphasized by the Rome criteria, is such only over a certain time period. It should also be emphasized that functional diseases are especially relevant for pediatric practice, since they make up the vast majority of all diseases of the digestive system in children. The prevalence of functional disorders in the structure of gastrointestinal tract diseases in children is not only high, but continues to grow every year. Thus, functional dyspepsia syndrome is observed in 30–40% of cases, chronic duodenal obstruction in 3–17% [1].

All motor disorders of the digestive tube can be grouped as follows:

- Change in propulsive activity:

- – decrease – increase.

- Changes in sphincter tone:

- – decrease – increase.

- The appearance of retrograde motility.

- The emergence of a pressure gradient in adjacent parts of the digestive tract.

The clinical symptoms of motility disorders of the digestive organs are diverse and depend on the localization of the process, its nature and the root cause. They can manifest as diarrhea or constipation, vomiting, regurgitation, abdominal pain or discomfort and many other complaints.

The patient’s somatic symptoms (complaints) are essentially the interpretation by the human mental sphere of information from receptors located in the internal organs. Its formation is influenced not only by the pathological process as such, but also by the characteristics of the nervous system and mental organization of the patient. The actual complaint presented to the doctor in this way is determined by the nature of the pathology, the sensitivity of the receptors, the characteristics of the conduction system and, finally, the interpretation of information from the organs at the level of the cerebral cortex. At the same time, the last link often has a decisive influence on the nature of complaints, leveling them in some cases and aggravating them in others, as well as giving them an individual emotional coloring.

The flow of impulses from peripheral receptors is determined by the level of their sensitivity or hypersensitivity to the action of damaging stimuli, manifested by a decrease in the threshold of their activation, an increase in the frequency and duration of impulses in nerve fibers with an increase in the afferent nociceptive flow. In this case, stimuli that are insignificant in strength (for example, stretching of the intestinal wall) can provoke an intense flow of impulses into the central parts of the nervous system, creating an image of a severe lesion with a corresponding autonomic response.

Thus, we can distinguish three levels of formation of a somatic symptom (complaint), for example pain: organ, nervous, mental. The symptom generator can be located at any level, but the formation of an emotionally charged complaint occurs only at the level of mental activity. In this case, a pain complaint generated without damage to the organ may not differ in any way from one that arose as a result of true damage.

As in the case of pain, complaints associated with impaired motility of the gastrointestinal tract can be formed at the level of the affected organ (stomach, intestines, etc.), associated with a violation of the regulation of these organs by the nervous system, but can also be generated regardless of the state of the organ, due to the peculiarities of the patient’s psycho-emotional organization. Compared to the mechanism of pain, the difference is associated only with the direction of nerve impulses: in the case of pain, there is an “ascending” direction, and the overlying level can become the generator of the complaint without the participation of the underlying one, while in the case of impaired motility of the gastrointestinal tract, the opposite situation is observed: “descending” impulse with the possibility of generating a symptom by the underlying organ without the participation of the overlying one. Finally, it is possible to generate a descending stimulus at the segmental level in response to a pathological ascending impulse, for example, with receptor hyperreactivity. Mechanisms associated with a decrease in the sensitivity threshold of intestinal receptors in combination with its stimulation by upper regulatory centers, activated against the background of psychosocial influences, are observed, in particular, with irritable bowel syndrome.

Thus, any symptom (complaint) becomes such only when scattered nerve impulses are processed by higher departments. A true somatic complaint is determined by damage to one or another internal organ, and various parts of the nervous system perform the functions of a connecting link and primary data processing, transmitting the latter to the mental level or in the opposite direction. At the same time, the generator of somatic-like complaints can be the nervous system itself and its higher parts. At the same time, the mental level is absolutely self-sufficient and here complaints can “emerge” that do not have their prototype at the somatic level, but are indistinguishable from true somatic symptoms. It is these mechanisms that underlie functional motor disorders. Differentiation of the primary level of the symptom (complaint) is of fundamental importance for the correct diagnosis and selection of the optimal treatment plan.

Disturbances in the motility of the digestive organs of any origin inevitably cause secondary changes, the main ones of which are disturbances in the processes of digestion and absorption, as well as disturbances in the intestinal microbiocenosis. The listed disorders aggravate motor disorders, closing the pathogenetic “vicious circle” [2].

The digestive organs have electrical activity that determines the rhythm and intensity of muscle contractions and motor skills in general. The question of the localization of the electrical pacemaker of the gastrointestinal tract remains open. Studies have shown that the pacemaker of the stomach is located in the proximal part of the greater curvature, and for the small intestine this role is played by the proximal duodenum (some authors localize it in the area of the confluence of the common bile duct), which generates slow electrical waves that are the highest for the entire small intestine frequencies. In addition, it has been proven that any zone of the gastrointestinal tract is a source of rhythm for caudally located segments or becomes so under certain conditions. The speed of propagation of the basic electrical rhythm in different parts of the gastrointestinal tract is not the same and depends on its functional state and the pacemaker. For the stomach, it ranges from 0.3–0.5 cm/sec (in the fundus) to 1.4–4.0 cm/sec (in the antrum). It should be noted that there is always a gradient of both the basic electrical rhythm and the rhythmic contractions of the smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract in terms of the frequency and speed of excitation in the caudal direction [3, 4, 5, 6].

To assess the nature of the motility of the digestive organs, X-ray (contrast) and electrophysiological research methods (electrogastroenteromyography) can be used. The latter have now received a new impetus for development and implementation on the basis of a new technical base and computer technologies, which have made it possible to carry out complex mathematical analysis of the obtained data in real time. The method is based on recording the electrical activity of the digestive organs.

Correction of motility disorders of the digestive organs comes down to solving three problems:

- treating the underlying cause;

- correction of actual motor disorders;

- correction of secondary changes that arose against the background of dyskinesia of the gastrointestinal tract.

Since the root cause of functional disorders is most often a violation of the nervous regulation of the digestive organs, the first task in this case should be solved by gastroenterologists in close contact with neurologists, psychoneurologists and psychologists after a thorough examination of the patient [7]. In the case of primary pathology of the digestive organs, for example with a peptic ulcer, treatment of the underlying disease comes first.

The second problem is solved by prescribing postural therapy, nutritional correction and medications. Postural therapy is most important in the correction of gastroesophageal reflux. It is recommended to ensure an elevated position of the head end of the patient's bed, avoid tight clothing and tight belts, physical exercises associated with overstraining the abdominal muscles, deep bends, prolonged stay in a bent position, lifting weights of more than 8-10 kg with both hands. Infants should be placed in an upright position during feeding and immediately after feeding. In the diet, you should limit or reduce the content of animal fats, increase the protein content, avoid irritating foods, carbonated drinks, reduce the single volume (you can increase the frequency) of food intake. In addition, you should not eat before bed. Obese patients are advised to lose weight. These and some other problems in infants are solved by prescribing special antireflux mixtures. If possible, you should avoid taking drugs that reduce the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, including sedatives, hypnotics, tranquilizers, theophylline, anticholinergics, beta-agonists. If you smoke, you must stop.

In case of intestinal pathology, poorly tolerated foods (causing pain, dyspepsia) and promoting gas formation are excluded: fatty foods, chocolate, legumes (peas, beans, lentils), cabbage, milk, brown bread, potatoes, carbonated drinks, kvass, grapes, raisins. Fresh vegetables and fruits are limited. Other foods and dishes are prescribed depending on the predominance of diarrhea or constipation in the clinical picture.

In general, the diet is determined by the underlying disease.

For the purpose of drug correction of the motility of the digestive organs, prokinetics and antispasmodics are used. The list of prokinetics used by domestic gastroenterologists is relatively small. These include metoclopramide, domperidone and trimebutine.

The action of domperidone (Motilium), as well as metoclopramide (Cerucal, Reglan), is associated with their antagonism towards dopamine receptors of the gastrointestinal tract and, as a result, increased cholinergic stimulation, leading to increased sphincter tone and accelerated motility. Unlike domperidone, metoclopramide penetrates well through the blood-brain barrier and can cause serious side effects (extrapyramidal disorders, drowsiness, fatigue, anxiety, as well as galactorrhea associated with an increase in prolactin levels in the blood), which makes it necessary to avoid its use in pediatric practice. The only situation when metoclopramide is indispensable is emergency relief of vomiting, since other prokinetics are not available in injectable forms. Motilium is prescribed at a dose of 2.5 mg per 10 kg of body weight 3 times a day for 1–2 months. Side effects of Motilium (headache, general fatigue) are rare (in 0.5–1.8% of patients).

The effect on motor skills and the possibility of using somatostatin analogs (octreotide) for functional disorders in both adults and children are also being studied. Somatostatin has been shown to reduce gastrointestinal motility and can be used successfully in a number of functional disorders, but specific indications and route of administration have not yet been developed [8, 9].

Loperamide (Imodium) occupies a special place among drugs that affect motility. The point of pharmacological application of this drug is the opiate receptors of the colon, the effect on which leads to a significant, dose-dependent, more pronounced slowdown of motility compared to trimebutine. Loperamide is a highly effective symptomatic antidiarrheal agent and can be used in combination with other drugs. Its use should be quite careful, because against the background of slowing motility, intestinal absorption increases, which can lead to severe intoxication, especially in patients with infectious diarrhea or severe intestinal dysbiosis.

In many cases, in addition to disturbances in propulsive activity, sphincter spasm occurs. In these cases, antispasmodics become the key drugs, not only normalizing muscle tone, but also eliminating pain. Several groups of drugs have antispasmodic effects on the digestive organs. These include M-anticholinergics (starting with atropine, which has gone out of clinical practice), myotropic antispasmodics acting through the suppression of phosphodiesterase (for example, drotaverine (No-shpa)), a selective blocker of calcium channels of intestinal cells (pinaverium bromide (Dicetel)) and a highly effective modulator Na+- and K+-channels (mebeverine (Duspatalin)).

Drotaverine, by inhibiting phosphodiesterase IV, increases cAMP concentrations in myocytes, which leads to inactivation of myosin kinase, inhibits the connection of myosin with actin, reducing the contractile activity of smooth muscles, and promotes relaxation of sphincters and a decrease in the force of muscle contractions.

Pinaveria bromide (Dicetel) blocks voltage-dependent calcium channels of intestinal myocytes, sharply reducing the entry of extracellular calcium ions into the cell and thereby preventing muscle contraction. Features of the drug are its selectivity for the digestive organs, including the biliary tract, as well as the ability to reduce visceral sensitivity without affecting other organs and systems, including the cardiovascular system.

A special feature of mebeverine (Duspatalin) is its dual action. On the one hand, it blocks fast Na+ channels, preventing depolarization of the muscle cell membrane and the development of spasm, while disrupting the transmission of impulses from cholinergic receptors. On the other hand, mebeverine blocks the filling of Ca++ depots, depleting them and thereby limiting the release of K+ from the cell, which prevents the development of hypotension. Thus, mebeverine has a modulating effect on the sphincters of the digestive organs, which not only relieves spasms, but also prevents excessive relaxation. A special feature of Duspatalin is its release form: 200 mg of mebeverine are enclosed in microgranules coated with a pH-sensitive shell, and the microgranules themselves are enclosed in a capsule. In this way, not only the greatest effectiveness of the drug is achieved, but also prolongation of its action over time and throughout the entire gastrointestinal tract. The drug, gradually released from the granules, ensures a uniform effect for 12–13 hours. Duspatalin is prescribed orally 20 minutes before meals, 1 capsule 2 times a day (morning and evening).

Mebeverine has been produced since 1965, and many years of experience in its use have shown not only the effectiveness of the drug, but also its safety. An important feature of the drug is the absence of anticholinergic effects, which significantly expands the scope of its application.

For flatulence, medications are prescribed that reduce gas formation in the intestines by weakening the surface tension of gas bubbles, leading to their rupture and thereby preventing stretching of the intestinal wall (and, accordingly, the development of pain). Simethicone (Espumizan) and combination drugs can be used: Pankreoflat (pancreatic enzymes + simethicone), Unienzyme with MPS (plant enzymes + sorbent + simethicone).

For constipation, the prescription of laxatives and/or prokinetics is indicated, however, in the latter group of drugs there are no effective drugs approved for use in pediatric practice, and of the laxatives, the most effective and safe drug in all age groups is lactulose (Duphalac).

The main feature of lactulose is its prebiotic effect. Prebiotics are partially or completely indigestible food components that selectively stimulate the growth and/or metabolism of one or more groups of microorganisms living in the large intestine, ensuring the normal composition of the intestinal microbiocenosis. From a biochemical point of view, this group of nutrients includes polysaccharides and some oligo- and disaccharides.

As a result of microbial metabolism of prebiotics in the colon, lactic acid, short-chain fatty acids, carbon dioxide, hydrogen, and water are formed. Carbon dioxide is largely converted into acetate, hydrogen is absorbed and excreted through the lungs, and organic acids are utilized by the macroorganism, and their importance for humans can hardly be overestimated.

Lactulose is a disaccharide consisting of galactose and fructose. Its prebiotic effect has been proven in numerous studies. Thus, in a randomized, double-blind, controlled study on 16 healthy volunteers (10 g/day of lactulose for 6 weeks), a significant increase in the number of bifidobacteria in the colon was shown [10].

The laxative effect of lactulose is directly related to its prebiotic effect and is due to a significant increase in the volume of colon contents (by approximately 30%) due to an increase in the bacterial population. An increase in the production of short-chain fatty acids by intestinal bacteria normalizes the trophism of the colon epithelium, improves its microcirculation, ensuring effective motility, absorption of water, magnesium and calcium. The incidence of side effects of lactulose is significantly lower compared to other laxatives and does not exceed 5%, and in most cases they can be considered minor. The safety of lactulose determines the possibility of its use even in premature infants, proven in clinical trials [11, 12].

The dose of lactulose (Duphalac) is selected individually, starting with 5 ml once a day. If there is no effect, the dose is gradually increased (by 5 ml every 3-4 days) until the desired effect is obtained. Conventionally, the maximum dose can be considered in children under 5 years old 30 ml per day, in children 6–12 years old - 40–50 ml per day, in children over 12 years old and adults - 60 ml per day. The frequency of administration can be 1-2 (less often - 3) times a day. A course of lactulose is prescribed for 1–2 months, and, if necessary, for a longer period. The drug is discontinued gradually under control of stool frequency and consistency.

Adsorbents, among which Smecta occupies the first place, also regulate motility to a certain extent. It is important that smectite (the active principle of the drug Smecta), in addition to the direct adsorbing effect, has mucocytoprotective properties and helps slow motility and has a beneficial effect on the composition of the intestinal microflora, being a synergist of probiotics.

The third task in the correction of motility disorders is to influence the disorders that arise against the background of dyskinesia of the digestive tract. Motility disorders (both slowing and accelerating) lead to disruption of the normal processes of digestion and absorption and changes in the composition of the internal environment of the intestine. A change in the composition of the internal environment in the intestine affects the composition of the microflora with the development of dysbacteriosis, and also aggravates existing disorders of the digestive processes, in particular, due to changes in the pH of the intestinal contents. In the future, damage to the epithelium and the development of an inflammatory process are possible, marking the transition from functional disorders to a disease with a well-defined morphological substrate. Thus, on the one hand, to correct impaired motility, it is advisable to use drugs with prebiotic activity (including lactulose), and, on the other hand, in the complex treatment of functional disorders of the digestive tract, if necessary, drugs of pancreatic enzymes should be included ( preferably highly effective microspherical, for example, Creon), adsorbents (Smecta), probiotics (Bifidum-bacterin forte and similar).

In general, the determination of the composition of therapy should be strictly individual, taking into account the pathogenetic features of the process in a particular patient with mandatory correction of the root cause of digestive motility disorders.

Literature

- Handbook of pediatric gastroenterology. Ed. A. M. Zaprudnova, A. I. Volkova. M.: Medicine, 1995.

- Belmer S.V., Khavkin A.I., Gasilina T.V. Functional disorders of the digestive organs in children. Educational and methodological manual. M., 2006. 42 p.

- Ponomareva A.P., Belmer S.V., Karpina L.M. Electromyographic assessment of intestinal motor function in children // Issues of modern pediatrics. 2006. T. 5. No. 6. P. 32–35.

- Klimov P.K., Barashkova G.M. Physiology of the stomach: mechanisms of regulation. L.: Nauka, 1991. pp. 57–69.

- Klimov P.K., Ustinov V.N. Bioelectric activity of smooth muscles of the digestive tract and its connection with contractile activity // Advances in physiological sciences. 1973. T. 4. No. 4. P. 3–33.

- Ustinov V.N. Biopotentials of smooth muscles and contractile activity of the stomach // Physiological Journal of the USSR named after. I. M. Sechenov. 1975. T. 61. No. 4. P. 620–627.

- Clouse RE, Lustman PJ, Geisman RA, Alpers DH Antidepressant therapy in 138 patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a five-year clinical experience // Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 1994. Vol. 8. No. 4. P. 409–416.

- Di Lorenzo C., Lucanto C., Flores AF, Idries S., Hyman PE Effect of octreotide on gastrointestinal motility in children with functional gastrointestinal symptoms // J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 1998. Vol. 27. No. 5: P. 508–512.

- Haruma K., Wiste JA, Camilleri M. Effect of octreotide on gastrointestinal pressure profiles in health and in functional and organic gastrointestinal disorders // Gut. 1994. Vol. 35. No. 8. P. 1064–1069.

- Bouhnik Y., Attar A., Joly FA, Riottot M., Dyard F., Flourie B. Lactulose ingestion increases faecal bifidobacterial counts: a randomized double-blind study in healthy humans // Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004. Vol. 58. No. 3. P. 462–426.

- Gleason W., Figueroa-Colon R., Robinson LH et al. A double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of lactulose in the treatment of encopresis in children with chronic constipation // Gastroenterol. 1995. Vol. 108. Suppl. 4. P. A606.

- Belmer S.V. Treatment of constipation in children of the first years of life with lactulose preparations // Children's Doctor. 2001. No. 1. P. 46–48.

S. V. Belmer , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor T. V. Gasilina , Candidate of Medical Sciences

RGMU, Moscow

Contact information about the author for correspondence