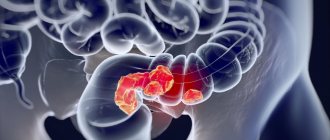

Intestinal obstruction is a set of symptoms that occurs as a result of disruption of the movement of food through the intestines. This is a very dangerous condition that can be fatal despite treatment. Death can occur from peritonitis and intestinal necrosis. Timely diagnosis and initiation of treatment is critical.

As the name implies, small intestinal obstruction occurs when there is a disruption in the passage of food at the level of the small intestine - duodenum, jejunum and ileum.

Causes and types of intestinal obstruction

Depending on the causes of development, the following types of intestinal obstruction are distinguished:

- Dynamic or functional obstruction - develops due to a violation of the contractility of the intestinal wall caused by spasms or paralysis.

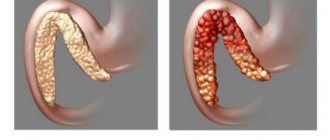

- Mechanical obstruction. This pathology develops due to the closure of the intestinal lumen, as a result of which the movement of intestinal contents becomes impossible. Such situations arise when the intestinal lumen is obstructed by a tumor, helminths, calculi, intestinal torsion during adhesions, etc.

Different parts of the small intestine have their own causes for the development of obstruction. For example, at the level of the duodenum, this condition occurs with cancer of the head of the pancreas or bile duct, as well as with cancer of the duodenum.

Obstruction at the level of the jejunum and ileum often occurs due to hernias, adhesions, helminthic infestations, and obstruction by foreign bodies. As for tumors, they rarely occur in this part of the intestine. However, obstruction can be caused by compression of the intestine from the outside by a tumor of another location, for example, with peritoneal carcinomatosis, colon or stomach cancer.

Mechanism of development of small intestinal obstruction

The development of intestinal obstruction occurs in several stages, and a cascade of pathological reactions is observed that have a systemic effect on the entire body. At the first stage, when obstruction has just occurred, the intestine begins increased peristaltic movements, as if trying to overcome the site of occlusion. This causes spasmodic pain, which either increases or subsides for a short time.

As contents accumulate in the afferent section of the intestine, this section begins to overstretch and peristalsis weakens and then stops altogether. This indicates paralysis of the intestines and is a formidable sign.

In parallel with this, parietal intestinal digestion is disrupted due to disruption of the nutrition of enterocytes (cells lining the surface of the intestine from the inside). They gradually die off, and their regeneration does not occur. Under such conditions, symbiont digestion comes to the fore due to the activation of intestinal bacteria. It is not physiological and leads to activation of the processes of decay and fermentation; decay products accumulate in the intestines, which have a general toxic effect. As the process develops, anaerobic bacteria begin to predominate in the intestinal flora, which secrete exo- and endotoxins. When absorbed into the blood, they lead to inhibition of the nervous system, disruption of blood microcirculation and the development of metabolic disorders.

As a result of such exposure, the intestinal wall becomes permeable to these bacteria, they begin to penetrate the bloodstream, leading to the development of systemic infectious processes - peritonitis and sepsis.

Also, at the same time, a violation of the water-electrolyte balance occurs. Under normal conditions, about 8-10 liters of liquid enter the intestines of an adult (this takes into account not only food, but also saliva, as well as the secretion of the digestive glands). In this case, about 80-90% of this liquid is absorbed. But with intestinal obstruction, reabsorption is impaired, and fluid accumulates in the adductor section of the intestine. Moreover, due to impaired microcirculation, increased filtration of fluid occurs, which leads to its release from the tissues. This will increase the volume of the already overstretched intestine. Ultimately, this leads to vomiting, which further aggravates the overall dehydration of the body and provokes the development of heart and kidney failure.

Rehabilitation

The main goal in the early postoperative period is to restore normal function of the gastrointestinal tract. The amount of time required for rehabilitation will be determined by the attending physician and depends on the extent of the surgical intervention, the age and general condition of the patient, and the presence of chronic diseases.

Most of our patients remain in the clinic for five to seven days after surgery due to intestinal obstruction. During this period, patients are under the supervision of a medical team, including surgeons, resuscitators, doctors of other specialties and nurses.

After discharge from the hospital, you need to remember important things:

- If you do not take care of the wound, it may become infected (redness, increased local temperature, swelling) and, as a result, complications in its healing. Therefore, it is necessary to remember and follow the recommendations given by your doctor. If bleeding occurs, go to the clinic to treat the wound.

- Early activation of the patient in the postoperative period helps reduce the risk of thromboembolic complications (for example, stroke, pulmonary embolism). In this case, heavy physical labor should be avoided for 5-6 weeks after surgery.

- It is necessary to adhere to a gentle diet for up to six weeks after surgery. Food that increases intestinal motility and gas formation (vegetables, fruits, organ meats, nuts, carbonated drinks) should be excluded from the diet. Portions should be small for easier digestion.

- It is necessary to adhere to the treatment prescribed by the attending physician. It is possible to prescribe medications to promote adequate pain relief. Your doctor may also stop some medications that you have been taking for a long time while you are recovering.

If you have questions about examination and treatment, you can always contact GMS Hospital for consultation. Our doctors are always happy to help you.

Symptoms of small intestinal obstruction

Symptoms of intestinal obstruction are quite specific and characteristic:

- Pain. In acute intestinal obstruction, it occurs suddenly and has an increasing character. It reaches its greatest peak against the background of peristaltic contractions, and then may weaken for several minutes. A few hours after the onset of the disease, the pain becomes unbearable. In the absence of treatment, it subsides for about 2-3 days, when intestinal paralysis develops. This is a very formidable sign, which is why it is called a symptom of grave silence.

- Vomit. With small intestinal obstruction, vomiting develops quite quickly and is associated with reflex irritation of the gastrointestinal tract.

- Bloating. With intestinal obstruction, bloating has characteristic features - the abdomen becomes asymmetrical, you can palpate the bulge of the adductor intestine and even see its peristaltic contractions. When percussed, a tympanic sound is heard.

In the clinical picture of small intestinal obstruction, three stages are distinguished:

- Early stage—it lasts up to 12 hours from the onset of the first symptoms. The main symptoms of this period are increasing abdominal pain and vomiting (in some cases it may be absent).

- The intermediate stage lasts from 12 hours to a day. At this stage, symptoms increase, and a full-fledged clinical picture unfolds. The pain becomes very severe and even unbearable, the abdomen enlarges, and symptoms of dehydration develop.

- Late stage - the period after a day from the onset of clinical manifestations of intestinal obstruction. The patient's condition rapidly deteriorates, symptoms of intoxication increase, temperature increases, changes in acid-base and electrolyte balance are noted, and failure of the cardiovascular and respiratory systems occurs. At the same time, peritonitis and sepsis develop.

Diagnosis of intestinal obstruction

The presence of intestinal obstruction can be suspected based on the characteristic clinical picture. If such a diagnosis is suspected, the patient should be immediately taken to the hospital, and diagnostic measures should be carried out simultaneously with therapeutic measures. This is necessary to stabilize the patient’s condition, replenish the lack of fluid in the body and prevent electrolyte disturbances.

To confirm the diagnosis, a plain radiography of the abdominal cavity is performed in the supine and standing positions. With intestinal obstruction, there will be signs of dilation of the intestinal loops and filling with gases. Additional methods that can be used are:

- Fibrogastroduodenoscopy will detect obstruction at the level of the duodenum and, in some cases, even carry out therapeutic manipulations, for example, removing gallstones or installing a stent that will support the intestinal walls in a straightened state.

- CT scan. It allows you to detect abdominal tumors that lead to compression and obstruction of the small intestine. The size of the tumor, the length of the stenosis, the interaction of the tumor with surrounding tissues, and the presence of metastases are also determined.

- In some cases, the diagnosis is made only during urgent surgery, for example, laparotomy or laparoscopy.

Introduction

The development of postoperative complications directly affects the results of treatment of surgical patients in general. The most difficult in terms of diagnostics and severe in clinical manifestations among postoperative complications is acute early adhesive small bowel obstruction (EAIOS), which occurs in 0.09-6.7% of patients who have undergone surgical interventions in the abdominal cavity [1-15]. And among all complications for which relaparotomy was performed, it is 8.3-14.3% [16-22]. The incidence of ORSTKN ranges from 50 to 93.3% of all types of mechanical obstruction of non-tumor origin and from 9.1 to 27.3% of the total number of all postoperative complications. Mortality in this pathology ranges from 14.2 to 52.4%, reaching 55-68% in patients over 60 years of age with severe concomitant pathology [23-28]. S. Sajja (2004) and others note a recurrent course of the disease in the form of acute adhesive small-bowel obstruction (ASIO) after surgery for adhesive small-bowel obstruction, where the cumulative percentage of recurrence for patients who had at least one small-bowel obstruction after 10 years was 18 %, after 30 years - 29% [14]. Surgery reduces the risk of recurrent episodes of ACBI, but not the risk of recurrent surgery. The overall percentage of relapses due to OSCI, according to a number of authors, varies from 19 to 53%. R. Stewart et al. [29] defined early postoperative small bowel obstruction (EPSO) as persistent bowel dilatation and constipation (the English word “obstipation” is most accurately translated as “absence of stool”; it is not an adequate replacement, since it requires an indication of duration, and in the therapeutic term “constipation” according to The definition is based on the absence of stool for 3 days, which developed after restoration of gastrointestinal motility, within 4 weeks after laparotomy, confirmed at a repeat operation. It is important that the pathogenesis, diagnosis, treatment tactics and types of surgical interventions in patients with ORSTCI have some differences from patients who have not had abdominal surgery and from patients with late ACS.

OSBI is subdivided into ORSBO, which develops during the first 30 days after surgery, and late OSBO, which develops after 30 days [2, 6, 7, 14, 25, 28, 30-35]. These dates were not chosen by chance, since they correspond to the completion of the process of adhesions in the abdominal cavity. Adhesions form after any intraoperative damage to the peritoneum or due to contamination and infection of the peritoneum. These conditions lead to the development of an inflammatory response with activation of the complement system and the coagulation cascade, complemented by the exudation of fibrinogen-rich secretions. Thrombin converts fibrinogen into fibrin, which attaches to damaged surfaces. If fibrin degradation does not occur at this stage, colonization of the resulting matrix with fibroblasts and intensive formation of collagen begins, which leads to the transformation of fibrinous adhesions into fibrin ones. If fibrin degrades without any residue, fibrinous adhesions dissolve and complete regeneration of the mesothelium occurs. However, peritoneal injury caused by surgery or peritonitis has been shown to reduce fibrinolytic activity. This early balance between the formation and degradation of fibrin in the peritoneal cavity during and after surgery appears to be the main factor determining the development of postoperative adhesions [5, 24, 36–41].

Differential diagnosis of ORSTKN and acute early small bowel obstruction caused by other causes

In the early postoperative period, ORSTKN should be particularly distinguished from postoperative intestinal paresis and functional, paralytic intestinal obstruction, as well as acute small bowel postoperative obstruction caused by other causes. [2, 6, 16, 42-48]. Many patients after surgical interventions in the abdominal cavity have signs of postoperative intestinal paresis, the duration of which depends on a number of factors: the duration and volume of the surgical intervention, the underlying disease for which the operation was performed, the general condition of the patient and his concomitant pathology (the intervention can cause severe hypoalbuminemia, which in turn leads to intestinal edema), existing and acquired water and electrolyte disorders, the presence and severity of complications. The function of the small intestine is restored a few hours after the operation, and gastric peristalsis begins a little later; finally, colonic motility is activated 48–72 hours after surgery. For adhesive small intestinal obstruction, according to S. Sajja, a triad of symptoms is typical: cramping abdominal pain, vomiting and complete absence of stool accompanied by bloating [14]. Moreover, in the case of early postoperative adhesive intestinal obstruction, there is a “bright gap” that lasts 2-3 days after surgery. And with paresis and dynamic acute intestinal obstruction there is no “bright gap”. Using this definition, the authors report an incidence of 0.7% in a sample of 8098 patients. P. Sykes and P. Schofield [49] used a similar definition: complete mechanical SBO observed after surgery (in the same episode of hospital admission), confirmed by relaparotomy or autopsy. J. Pickleman and R. Lee [50], on the other hand, considered significant the presence of symptoms of obstruction for 7 or more days that arose within 30 days from the date of surgery, or as symptoms of obstruction that arose from the 7th to the 30th day. th day from the moment of surgery and lasting several days. J. Quatromoni et al. [51] supplemented this determination of clinical signs with X-ray examination of the abdominal cavity. E. Frykberg and J. Phillips [52] considered it acceptable to make a diagnosis of RPTBN in the presence of at least one of the 4 standard clinical signs of intestinal obstruction (abdominal pain, vomiting, dilatation of loops, constipation), confirmed by radiography. In another prospective study, S. Ellozy et al. [53] diagnosed RPTBN when cramping pain, vomiting and changes on the radiograph occurred after temporary normalization of intestinal function in the 30-day postoperative period - 9.5% of patients had such symptoms. K. Siporin et al. [54], in a retrospective analysis of medical records of 1475 patients after interventions on the abdominal aorta, revealed an incidence of the disease of 3%. It can probably be considered that the definition of R. Stewart et al. [55] does not describe the actual prevalence of RPTBO, excluding cases of spontaneous resolution of the obstruction; Most authors used the definition of S. Ellozy et al. [53].

A distinctive feature of ARTSCI is that it can occur at any time in the early postoperative period, characterized by significant variability in clinical symptom complexes. Most authors indicate the 3-8th day after the primary operation as the most common time period for the development of ARTSCI. And the most dangerous time period for the manifestation of postoperative complications and the development of ARTSCN is considered to be the 2-5th day [2, 6, 10, 16, 23, 43, 56-60]. Only with active dynamic monitoring of the patient is it possible to identify a clinical picture that is not typical for the usual, uncomplicated course of the postoperative period [61-64]. The lack of sufficiently reliable criteria and methods for diagnosing ARTSKN in the early postoperative period often leads to repeated surgery at a later stage or, conversely, to unnecessary relaparotomy [7, 14, 25, 34, 65—68].

According to a number of authors, during these periods, early dynamic small intestinal obstruction can occur in 58.8-78.8% of operated patients and also requires differential diagnosis with ORSTKN. Among the main causes of dynamic obstruction, peritonitis occupies a consistently leading place - 18.5-20.5%, and most often manifests itself as a combination of several causes - 30.4-32.5% (functional intestinal inferiority, hemoperitoneum, hematomas, inadequate decompression or early removal decompression, intestinal eventration, etc.) [9, 17, 24, 69].

ORSTKN also needs to be differentiated from acute postoperative small bowel obstruction of mechanical origin caused by other causes. Any tissue defect in the abdominal cavity can be a potential cause of small bowel obstruction due to the development of internal hernias, parietal strangulation, and especially in trocar defects of the anterior abdominal wall after laparoscopic operations [7, 8, 14, 17, 31, 32, 70]. When a defect occurs in the mesentery or omentum, the “pockets” behind the colostomy or enterostomy, the small intestine can become trapped in these structures, leading to obstruction [7, 10, 18]. In patients operated on for acute obstruction, there may be a cause of obstruction that was not diagnosed or eliminated during the primary operation, which can lead to recurrent small bowel obstruction. Small intestinal phytobezoars causing obstruction are often multiple in nature: undetected bezoars can cause recurrent obstruction requiring reoperation, as described in 6 of 77 patients treated for bezoar-induced obstruction [52]. An analogy can be drawn with operations for cholelithiasis, in which undetected intraintestinal stones or re-passage of the stone into the intestine through a vesico-enteric fistula can lead to RPTBO [71].

During surgical interventions performed for inflammatory diseases of the abdominal organs on an emergency basis, a local inflammatory reaction occurs in the form of an intra-abdominal abscess or phlegmon, which can lead to fixation of the loops of the small intestine with each other and with the walls of the abdominal cavity, leading to the formation of inflammatory conglomerates and small intestinal obstruction. Such “septic” or “inflammatory” adhesions were the cause of RPTBI in 3 of 41 [51] or 4% [53] of cases. In another study [49], intra-abdominal abscess was found in 12 of 26 patients with RPTBN. However, in such cases it is difficult to determine whether the obstruction was mechanical or paralytic.

Other rare causes of ARPTKN include intussusception and intramural hematoma of the small bowel. There are even descriptions of intussusception of the stump of the appendix after appendectomy [72]. RPTCN also occurs after retrocolic gastroenterostomy, most often performed without gastric resection, when the efferent loop of intestine invaginates into the lumen of the stomach. Like spontaneous intramural hematoma of the small bowel in patients on anticoagulants, a well-described cause of small bowel obstruction, hematoma of the small bowel wall or mesentery following surgery may present as RPTBO. Diffusely inflamed, fragile intestine in patients undergoing surgical treatment for complications of radiation enteritis is extremely predisposed to the development of early postoperative complications, including obstruction. Similarly, surgical patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis are at high risk for persistent or recurrent RPTCN, particularly when multiple obstructive areas are identified at initial surgery. Finally, a significant number of different complications of intestinal anastomoses, including anastomotic strictures due to anastomotic edema or leakage, can lead to RPTBI. Localized leakage due to focal anastomotic leakage, leading to the development of local phlegmonous inflammation, is often the cause of these conditions, but is rarely diagnosed [73].

Causes and risk of developing early postoperative small bowel obstruction depending on the primary pathology and primary surgery

The incidence of ARTSKN depends on the urgency of the primary intervention, the volume of the surgery undergone, the traumatic nature of the approach and the disease for which it was performed [2, 7, 16, 32, 43, 61, 73]. The dependence of the incidence of ARTSKN on the nature of the underlying disease for which surgical intervention was performed was traced. This complication most often developed after operations for atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta and its branches - 23.3%. In second place are patients operated on due to acute intestinal obstruction - 13.3%. It is somewhat less common in patients operated on for closed trauma and penetrating wounds of the abdominal cavity (8.7%) [14]. Studies have shown that the type of previous surgical intervention performed for the underlying disease also significantly affects the incidence of ARTSKN. According to the data obtained, it most often develops after operations on the intestines (30.1%), somewhat less frequently, complications occur after appendectomies (17.9%) and interventions on the biliary tract (14.8%). It should also be noted that ARTSKN occurs more often after emergency surgical interventions (68.5%) compared to planned operations [9]. ORSTKN occurs more often (2.8-17.9%) after operations performed via laparotomy compared to laparoscopic operations, accounting for 0.04-1.6% of cases [2, 6, 8, 13, 23, 19, 38, 52, 74]. In a prospective study by R. Stewart et al. [29] the most common causes of RPTBI were surgery for inguinal hernia obstruction, surgery on the left colon and rectum, and surgery on the small intestine. During appendectomy, there is an increased risk of developing RPTCN during operations for gangrenous-perforated appendicitis, but without any particularities during operations for non-perforated forms. In a cohort study by R. Andersson [75], among 245,400 people who underwent open appendectomy, the incidence of SBO within 4 weeks after surgery was 0.4%, with risk factors including perforated appendicitis, unnecessary appendectomy, and older age of patients. RPTBO is a common complication of total colectomy, occurring in 12.3% of patients after ileal-anal-reservoir reconstruction [76] and in 5.5% of patients after subtotal colectomy [77]. Removal of the greater omentum during such operations likely increases the risk of developing adhesive SBO by stimulating the development of adhesions between the small bowel and the anterior abdominal wall. According to V.V. Rybachkova et al. postoperative ileus in 125 patients often developed after appendectomy (22.0%), suturing wounds of hollow and parenchymal organs (18.1%), dissection of adhesions (13.3%) and gastric resection (12.2%) [45].

The low-traumatic nature of laparoscopic interventions in planned and emergency abdominal surgery in the form of a reduction in the development of adhesions in the abdominal cavity and postoperative complications has been proven by numerous publications [2, 7, 10-13, 18, 19, 73-78]. A multicenter study from France [11] describes the prevalence of SBO after laparoscopic surgery as 0.2%, with SBO accounting for up to 88% of all obstruction episodes. Cholecystectomy, hernia repair, and appendectomy most often resulted in RPCT. In half of the cases, the cause of obstruction was adhesions, and in another half, trocar hernias of the small intestine. All trocar hernias were associated with the use of 10- and 12-mm trocars, and the most common site of occurrence was the umbilicus. In the majority of these cases (66%), the fascial defect was not adequately closed [11]. Moreover, 5-mm trocars can also serve as a hernial orifice for the small bowel, leading to RPTBI [74]. A case of trocar hernia formation leading to RPTBI immediately after removal of intraperitoneal drainage has been described [79]. Another cause of RPSTKN after laparoscopic operations may be gallstones released into the free abdominal cavity during cholecystectomy - an inflammatory infiltrate often forms around them, which may involve the intestine. Cases of fixation of small intestinal loops to meshes in the area of hernioplasty have also been described [80]. A similar case was described with a clip applied during appendectomy [81].

Clinical symptoms of the disease

The clinical symptoms of early ACBI differ from late ACBI and have their own characteristics of manifestation, especially on the 3-7th day of the early postoperative period. At this stage, it is necessary to carry out a differential diagnosis with paresis of the gastrointestinal tract, paralytic small bowel obstruction and other causes of mechanical obstruction of the small intestine [2, 4, 6, 10, 19, 82, 83]. The diagnosis of ORSTKN is usually made late, or the clinical picture is interpreted as postoperative intestinal paresis. For mechanical small intestinal obstruction in the later postoperative period, a triad of symptoms is typical in the form of cramping abdominal pain, vomiting and a complete absence of stool against the background of abdominal bloating, since for ORSTI in the early postoperative period a smoothed clinical picture is more typical, “blurred” due to the dynamic component obstruction, pain in the area of postoperative wounds and analgesic therapy. One example is a study in which only 15 of 26 patients complained of abdominal pain [52]. Vomiting was reported by investigators in 82% [50] and 20 of 26 cases [52] but was absent in cases where a previous nasogastric tube was present. A complete absence of stool is also uncharacteristic: patients often pass little gas, and sometimes have stool, which does not at all exclude RPTCI [49, 52]. Abdominal bloating is the only clinical sign consistently reported to be associated with ESCC, with an incidence of 76–81% [50, 52]. Although, against the background of cramping pain, the auscultatory picture of an “obstructed” bowel makes one suspect SBO, it is extremely difficult to differentiate it from high-frequency ringing sounds and uncoordinated elements of the normal sound picture, characteristic of postoperative intestinal paresis [49]. Some authors [52] believe that surgery is advisable if two or more of the above-mentioned signs are present; 20 of 26 patients with three or four features clearly required surgical treatment for persistent RPTBN. B.P. Shurkalin et al. (2010) the clinical symptoms of postoperative ileus in 80 patients were divided into three leading syndromes, which occurred with varying degrees of symptom severity: pain syndrome (independent pain of varying nature and intensity, pain on palpation, protective tension of the muscles of the anterior abdominal wall, Shchetkin-Blumberg symptom) ; signs of impaired passage through the gastrointestinal tract (bloating, vomiting, stool and gas retention, auscultation of bowel sounds, symptoms of Spasokukotsky, Val, Sklyarov, Obukhov Hospital); signs of water and electrolyte disorders (tachycardia, dry mucous membranes, changes in the biochemistry and electrolyte composition of the blood) [10]. V.V. Rybachkov et al. [45] characterized the clinical symptoms of ORSTCI as follows: the features of the clinical picture are a decrease in the frequency and a change in the nature of the pain syndrome, the appearance of symptoms of peritoneal irritation, recurrent intestinal paresis, a decrease in the frequency of dyspeptic disorders, severe tachycardia against the background of the absence of a temperature reaction and an imbalance of homeostasis indicators.

Analyzing the clinical symptoms according to the literature, we can conclude that ORSBO has a blurred clinical picture of small intestinal obstruction, which differs from late OSBO. It can manifest itself as a diverse set of symptoms, characteristic of numerous postoperative complications that occur in the early postoperative period. Features of the clinical picture are due to the development of complications against the background of postoperative trauma, the use of various medications, the progression of the underlying disease and concomitant pathology. All this requires a thorough assessment of the clinical picture of the disease over time and the use of modern instrumental research methods.

Diagnosis of ORSTKN

Most often, obstruction is diagnosed in cases where the patient has already begun to pass gas or had stool, but then these phenomena have stopped. However, patients often experience spontaneous improvement without an identified cause. If this does not happen, it is necessary to perform instrumental studies of the abdominal cavity to identify the nature of the pathology and plan a diagnostic and treatment program. Today, there are many diagnostic methods in the early postoperative period: laboratory tests, radiation, ultrasound and endoscopic methods. However, their use in practice is not always possible due to the complexity of use in critically ill intensive care patients or the low information content of the methods [14].

Plain radiography of the abdominal cavity in the standing and supine position is usually the first radiological examination prescribed for patients with signs of acute bowel syndrome or prolonged postoperative intestinal paresis. Distended loops of the small intestine with fluid levels and scanty volumes of gas content in the large intestine suggest RPSTCI. However, the interpretation of survey images is difficult; Both postoperative paresis and RPTBI may present with distension of small bowel loops and gas in the colon. The clinical reliability of plain radiography data ranges from 19 to 73% [2, 52, 82-84, 37]. X-ray contrast studies of the upper gastrointestinal tract are also used quite often. If orally administered contrast does not reach the colon, this supports the assumption of RPTBI, but the converse is not necessarily true; Contrast may well reach the colon in patients with obstruction, including those requiring surgical treatment for it. In one study [50], the radiocontrast method made it possible to localize the site of obstruction in 72% of patients. While radiologists commonly use barium because of its excellent radiopaque properties, clinicians prefer water-soluble contrast forms because barium tends to stagnate in obstructed small bowel, making subsequent CT examination difficult [16].

The gastrografin study is used in patients with ARVO to determine whether the episode of obstruction can resolve on its own or whether urgent surgical intervention is required. Gastrografin (Schering AG, Berlin, Germany), a hyper-osmolar drug that stimulates intestinal motility, and, by helping to resolve the symptoms of ORSTCI, reduces the likelihood of surgical treatment [85, 86]. Moreover, the administration of gastrografin for obstruction has been suggested to differentiate mechanical obstruction (contrast medium does not reach the colon) from intestinal paresis (contrast medium reaches the colon) [85] and hasten the resolution of both conditions [85, 86]. The results of the study with gastrografin must be compared with the clinical picture, since contrast may pass through in the area of partial or chronic narrowing. To consider an episode of obstruction resolved, it is necessary to ensure that all its symptoms have disappeared [2, 6, 16, 23, 56, 71].

In cases where the clinical picture makes one suspect an infectious or septic nature of paresis or RPTKN, the use of abdominal CT with gastrografin contrast is indicated in order to clarify the treatment and diagnostic program. Oral contrast-enhanced CT differentiates postoperative paresis from RPTBI with a sensitivity and specificity of 100%, compared with 19 and 100% for clinical examination with plain radiography. CT has the other advantage of being able to visualize intra-abdominal causes of paresis or RPTCI, such as abscess, perianastomotic cellulitis or anastomotic leak, hematoma, pancreatitis, or noncalculous cholecystitis. It also makes it possible to identify other causes of RPTBI—dehiscence of the aponeurosis, external or internal hernias [14, 82—86].

A number of authors believe that ultrasound is the most effective way to diagnose intestinal obstruction, which in the future will completely replace traditional X-ray examination [88-90]. In contrast to this opinion, E.A. Beresneva et al. (2004) [91], analyzing the results of using different radiation methods for acute intestinal obstruction (x-ray, ultrasound, radioisotope), came to the conclusion that none of them is absolute. Sonography has an advantage in the early stages of the disease, while X-ray examination is more effective in the later stages of obstruction. The greatest diagnostic efficiency (90.3-97.8%) is possible only when they are used together. The ultrasound method allows not only to ascertain the presence of acute obstruction, but also to more reliably determine the level, cause, form of obstruction, functional state and signs of impaired blood supply to the intestine [92]. S. Suri et al. [87] showed that with ultrasound the sensitivity of the study was 83%, specificity 100%, accuracy 84%, while with the X-ray method these figures were significantly lower: 77, 50, 70%, respectively. The diagnostic algorithm for RPTCN is shown in Figure [14].

Algorithm for the management of patients with early postoperative small bowel obstruction (EPSO).

Most authors, in order to successfully diagnose ARTSKN, use a comprehensive diagnosis of this disease with an assessment of the dynamics of the clinical picture, homeostasis indicators, X-ray and ultrasound data, and without fail use diagnostic laparoscopy as the final diagnostic method [1-4, 6-10, 14-17 , 34-38, 65-68].

Diagnostic laparoscopy

Some domestic and foreign authors have proven the safety and effectiveness of laparoscopy in diagnosing complications in patients in the early postoperative period with a diagnostic accuracy of the method ranging from 82 to 100% [2, 6, 10, 17, 19, 48, 62, 69, 83, 84, 93-98]. Diagnostic laparoscopy for postoperative ileus consisted of three stages: survey laparoscopy, differential diagnosis of postoperative obstruction (paralytic or mechanical), and a detailed examination of the abdominal cavity. During the audit, the following tasks were solved: the safety of puncture of the abdominal cavity and the absence of traumatic injuries to organs and tissues were assessed; the presence of postoperative disturbance of passage along the gastrointestinal tract was confirmed; the presence of signs of diseases, primarily peritonitis, which could be the cause of postoperative ileus, was determined; The possibility of further laparoscopic revision of the abdominal cavity was determined. According to their data, the effectiveness of laparoscopy for postoperative intestinal obstruction reached 100% [10].

Thus, despite numerous publications devoted to the successful use of modern non-invasive instrumental methods (x-ray, ultrasound, CT) in the diagnosis of late ACBI, even when used together, they cannot always answer all the questions of interest to specialists, especially in the diagnosis of early ACBI. There remains a certain percentage of diagnostic errors and inaccuracies that can lead away from choosing the correct treatment tactics, which leads to worse treatment results for this complex and severe category of patients. Diagnostic algorithms that are used in foreign clinics cannot always correspond and be used in Russian healthcare due to the peculiarities of domestic medicine in the field of equipment for emergency surgical care hospitals. Therefore, the search for diagnostic methods for ARTSCN remains relevant at the present stage of development of medicine [6, 12, 14, 23, 35, 41, 52, 67, 99-101].

Therapeutic tactics for ARTSKN

The final issue of treatment tactics for ARTSKN has not yet been completely resolved and continues to be discussed in medical circles in our country and abroad. ORSTKN with its clinical features, diagnostics and course characteristics further increases the need for correct tactical decisions regarding conservative or surgical treatment. Some authors strive to maximize the use of conservative therapy, while other authors are proponents of active surgical tactics [2, 6, 16, 34, 96, 102-105]. The therapeutic approach to the treatment of ARTSKN, according to many authors, should be differentiated depending on the form and severity of obstruction. Therapeutic tactics for ORSTKN can be based on the identification of two forms of obstruction: strangulation and obstruction (simple). The strangulation form is manifested by clinical signs of impaired passage through the intestine and signs of impaired blood supply in the organ, and occurs with simultaneous compression of the intestinal lumen and the vessels of the mesentery of the small intestine. Obstruction or (“simple”) form is characterized by impaired passage through the intestine without signs of impaired blood supply in the intestine. In the first case, emergency surgery is indicated within 2-3 hours from the appearance of the ORSTKN clinic due to the risk of developing necrosis of the small intestine, and in the second case, conservative therapy is possible for 24-48 hours and up to 5-7 days, according to foreign data authors, with active clinical and instrumental observation with subsequent resolution of the issue of urgent surgical treatment [2, 6, 11, 13, 15, 19, 22, 25, 37, 41, 62-67, 71-73]. In cases of ARTSCI complicated by peritonitis, S.A. Aliev et al. It is recommended to perform emergency surgery 2-3 hours after intensive preoperative preparation [16, 23, 27, 93].

One of the main factors determining the management of patients with SBO is the risk of developing a strangulation form of obstruction. It is well known that the reliability of clinical and laboratory data in the early detection of strangulation is low, and their use is a compromise [106]. However, in contrast to late OSBO and other forms of small bowel obstruction, the risk of strangulation is extremely low and is observed from 1.8 to 4.6% according to a number of authors [6, 14, 34, 106]. It should be recalled that the risk of strangulation is higher in patients with internal strangulations or trocar hernias and mural strangulations, but such information is available only on isolated cases of the disease in the absence of data on large samples [12, 58]. If on the 5th day after laparotomy the patient still has clinical signs of RPTBO or intestinal paresis, plain films of the abdominal cavity should be obtained. If the findings suggest paresis or RPTBN, a gastrografin test can be used to both differentiate between the two conditions and help resolve them. If the clinical picture suggests one of the above-mentioned intra-abdominal causes of persistent intestinal paresis, or if, based on the characteristics of the surgery, the presence of strangulation is suspected, CT with intra-abdominal contrast gastrografin is indicated [14]. Insertion of a nasogastric tube, if not already in place, is necessary to prevent aerophagia, gastric decompression, relieve nausea and vomiting, and to measure gastric volumes. Biochemical studies should be performed and, if there are deviations, they should be corrected. Since intestinal paresis is most often caused by opiates, their use should be limited as much as possible, even to the point of prescribing specific antagonists [4, 7, 10, 13, 82]. Severe hypoalbuminemia can lead to generalized edema, which extends to the intestine; This swollen, swollen intestine is described by the term “hypoalbumin enteropathy” and does not have normal motility. It is important to distinguish this condition from RPTCN [47].

Thus, the treatment tactics for ARSTKN have two completely opposite treatment options for this complex category of patients: active - with the need to perform surgery in the first 2-4 hours from the onset of the ARSTKN clinic and conservative - with the possibility of carrying out conservative treatment measures for from several hours to 6 —12 days, including endoscopic nasointestinal decompression (ENID), with appropriate indications and contraindications. It is possible to improve the results of treatment of ARTSKN only through a differentiated approach to the timing of surgical intervention depending on the form of intestinal obstruction, its severity and the presence of complications. The use of modern endoscopic technologies (endoscopy and laparoscopy) further aggravates the situation in terms of determining treatment tactics and their capabilities in a complex algorithm for diagnosing and treating ARTSCN. Undoubtedly, a balanced and meaningful approach to the use of modern technologies will determine their place in improving the results of diagnosis and treatment of ARTSCN [2, 6, 10, 16, 22, 70, 82, 98].

Conservative therapy for ARTSCN

Conservative therapy, assessment of the timing of its effectiveness and the time of transition to surgical treatment are of great importance for the results of treatment of patients with ARTSCN. On the one hand, conservative therapy can be an independent and definitive method of treatment, and on the other hand, if it is ineffective, it is a positive factor in the preoperative preparation of the patient for surgery [2, 16, 82]. The need for early restoration of intestinal motor activity is due to the fact that long-term inhibition of motility, even in the absence of a mechanical obstacle, leads to disruption of the processes of secretion and absorption, increased vascular permeability [50, 81] and repeated adhesions [81]. Therefore, the lack of intestinal motility can lead to a progressive deterioration of the patient's condition. According to [2, 14, 25], in many cases, impaired intestinal motor function is unjustifiably explained by paresis rather than adhesive intestinal obstruction, which in turn forces a wait-and-see approach. In this regard, according to S. Sajja, diagnostic measures should be carried out simultaneously with therapeutic ones. If on the 5th day after laparotomy the patient still has symptoms of early postoperative adhesive small bowel obstruction or intestinal paresis, then it is necessary to perform a plain radiography of the abdominal organs with gastrografin [14].

In the absence of signs of intestinal ischemia

Treatment of small intestinal obstruction

As we have already said, treatment of obstruction begins at the stage of examining the patient. Infusions of rehydrating solutions are carried out, the loss of electrolytes is replenished, and the contents accumulated in the adductor section of the intestine are aspirated using a nasogastric tube. If necessary, antibiotics are prescribed. The main stage of treatment for intestinal obstruction is surgery, which should be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis. It is possible to delay the operation for 2-3 hours to stabilize the patient’s condition. Surgical intervention involves laparotomy - opening the abdominal cavity with subsequent revision and elimination of the causes that caused the development of obstruction:

- The adhesions are cut.

- Hernias are sutured.

- Remove stones or intestinal parasites.

During the operation, the viability of the intestine must be assessed. If there are signs of necrosis, resection of the affected area is performed.

The greatest difficulty is intestinal obstruction caused by malignant neoplasms. In this case, the operation is more extensive. If possible, the tumor is removed within healthy tissue. If this is not possible, palliative operations are performed, for example, bypass anastomoses are performed.

In case of extensive neoplasms or carcinomatosis of the peritoneum, anastomoses have a short-term effect and the obstruction recurs. In such cases, a stoma is indicated - the section of the intestine located above the obstruction is brought out onto the abdominal wall. The intestinal contents will be discharged into a special bag, a colostomy bag. This is a psychologically very difficult operation for patients, but only it can save their lives.

In these cases, if possible, antitumor treatment is carried out, and if the results are stable, reconstructive interventions are performed.

Prognosis and prevention for intestinal obstruction

The prognosis is determined by the cause of the obstruction. If it develops as a result of adhesive disease, intussusception, or the presence of foreign bodies, then the prognosis is favorable, although there are certain risks of relapse. To prevent it, preventive measures are carried out - hernias are sutured, adhesions are lysed. If the cause of obstruction is a tumor, then the prognosis depends on the possibility of its radical removal. In case of extensive malignant processes, treatment is palliative in nature and is aimed at alleviating the patient’s condition, prolonging his life and improving its quality.

Book a consultation 24 hours a day

+7+7+78

Advantages of treating abdominal adhesive disease at the Swiss University Hospital

- Our clinic employs experienced, highly qualified surgeons who have performed hundreds of operations to separate abdominal adhesions.

- The clinic is equipped with modern equipment that makes it possible to perform complex interventions with minimal blood loss, while the risk of intraoperative complications in case of adhesive disease of the abdominal cavity is minimal.

- To prevent the appearance of adhesions after surgery and the development of relapses in the future, we use effective anti-adhesive barriers that are safe and do not cause unwanted effects.

- The method of surgery for adhesive disease is selected individually for each patient, taking into account the characteristics of his health.

- Patients have at their disposal the possibility of extensive examination and preoperative preparation, all types of laboratory diagnostics, as well as wards of various categories, including for day hospital stay.