- What is acute intestinal obstruction?

- Classification

- Why does acute intestinal obstruction develop?

- Signs of intestinal obstruction

- Why is intestinal obstruction dangerous?

- What needs to be done to save a person with intestinal obstruction?

- Is stoma removal always necessary during surgery for intestinal obstruction?

- What happens to the removed stoma?

- Is it possible to help a patient without surgery?

Timely diagnosis and treatment of acute intestinal obstruction, including prevention of obstruction through endoscopic installation of stents, allows maintaining a high quality of life in patients with oncological diseases of the abdominal organs, and in some cases, saving lives. [1]

What is acute intestinal obstruction?

Acute intestinal obstruction is a serious, life-threatening complication of many diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, including tumors of the intestine itself, as well as tumors of other abdominal organs and retroperitoneal space.[2]

Despite the advances of medicine, if timely medical care is not provided in the first 4-6 hours of development, up to 90% of patients die from acute intestinal obstruction.

For patients with cancer of the colon and small intestine, especially in the later stages of the disease, in the presence of massive metastases in the area of the porta hepatis, it is important to know the first signs of the development of acute intestinal obstruction in order to promptly seek medical help at a medical institution.

The essence of acute intestinal obstruction is the rapid cessation of the normal physiological passage (passage) of food through the digestive tract.

Intestinal obstruction can be complete or partial. With partial obstruction, the passage of food is sharply limited. For example, with stenosis (compression) of the colon by a tumor conglomerate, its diameter can decrease to 1-3 mm. As a result, only a small amount of food can pass through such an opening. Such a lesion is diagnosed by gastroscopy or colonoscopy, depending on the location of the narrowing of the intestine.

To predict the treatment and outcome of this acute complication of cancer, it is extremely important to know whether the disruption of food passage occurred before or after the ligament of Treitz, formed by the fold of peritoneum that suspends the duodenum. Accordingly, therefore, high (small intestinal) and low (colon) obstruction are distinguished. [3]

Also, the prognosis for treatment of acute intestinal obstruction is determined by the presence or absence of a mechanical obstruction. If there is no obstacle to the passage of food in the form of complete compression of the intestinal tube, intestinal obstruction is called dynamic, which in turn can be paralytic or spastic.

If there is a mechanical obstruction in the path of food (usually a tumor, swelling of adjacent tissues caused by a tumor, or adhesions, including those arising as a result of previously performed surgical treatment of cancer), such intestinal obstruction is called mechanical (synonymous with obstructive).

When there is compression of the mesentery (folds of the peritoneum that support the intestine, through which blood vessels and nerves pass), intestinal obstruction is called strangulation. [5,8]

In case of dynamic intestinal obstruction, conservative treatment is prescribed in a surgical hospital. For mechanical and strangulation intestinal obstruction, treatment is only surgical.

What's the prognosis?

In most cases, intestinal obstruction occurs in advanced stages of cancer, so the question is how to improve the patient's condition and prolong his life, and not how to cure. This treatment is called palliative. The prognosis depends on the stage of the tumor and a number of other factors.

For example, the five-year survival rate for stage 4 cancers that can lead to intestinal obstruction is:

- Colon cancer - 11%.

- Rectal cancer - 12%.

- Small intestine cancer - 10%.

- Stomach cancer - 5%.

- Prostate cancer - 29–100%.

- Uterine cancer - 15–17%.

- Ovarian cancer - 19%.

- Bladder cancer - 15%.

Classification

Intestinal obstruction is not an independent disease, but is a symptom as a result of which the passage of contents through the intestines is stopped and disrupted. According to the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10), this condition is a complication of other diseases, which include the following nosologies: [7]

| Code | Nosology |

| K56 | Paralytic ileus and intestinal obstruction without hernia |

| K56.0 | Paralytic ileus |

| K56.1 | Intussusception |

| K56.2 | Volvulus |

| K56.3 | Ileus caused by gallstone |

| K56.4 | Another type of closure of the intestinal lumen |

| K56.5 | Intestinal adhesions [adhesions] with obstruction |

| K56.6 | Other and unspecified intestinal obstruction |

| K56.7 | Ileus unspecified |

In addition, intestinal obstruction can be classified according to the degree of passage disturbance, the level of obstruction, the clinical course, etiology and degree of compensation.

According to the degree of passage violation

- Full. The passage of intestinal contents is completely stopped.

- Partial. The passage of intestinal contents is partially preserved.

By level of obstruction

- High (if an obstruction occurs in the right parts of the colon).

- Low (obstruction occurs in the left colon or rectum).

According to the clinical course

- Spicy.

- Chronic.

According to the etiology of occurrence

- Tumor. The tumor can compress the intestines from the outside, in which case they speak of functional obstruction. If the tumor is inside the intestine, it is mechanical. When the tumor invades the nerve plexus, pseudo-obstruction may occur.

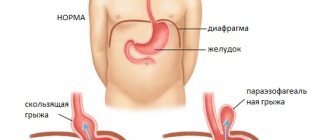

- Non-tumor. The cause may be a decrease in intestinal tone, constipation, fecal blockages, diverticulitis, infarction of the intestinal wall, hernias, adhesions, etc.

By degree of compensation

- Compensated. It occurs against the background of regular constipation with difficulty passing gas and stool retention.

- Subcompensated. The retention of gases and stool does not exceed 3 days.

- Decompensated. Retention of stool and gases exceeds 3 days, there are radiological signs of both small and large intestinal obstruction. [1,3,4]

How is the operation performed?

The extent of the operation depends on the location and cause of the intestinal obstruction. The main task of the surgeon is to eliminate the etiological factor; based on this, several types of operations are possible:

- Dissection of adhesions.

- Removal of part of the intestine in which irreparable changes have occurred. Under favorable conditions, the two sections of the intestine are stitched together. If immediate restoration of the intestine is not possible, then a stoma is formed (an artificial channel for emptying the intestines of feces).

- Elimination of volvulus, intussusception, nodule formation.

If intestinal obstruction occurs against the background of a tumor process, the scope of the operation will depend on the location, stage of the disease, complications caused by obstruction of the intestinal lumen.

Why does acute intestinal obstruction develop?

Among the factors predisposing to mechanical intestinal obstruction, the most common are:

- Adhesive process in the abdominal cavity (as a consequence of the interaction between the tumor and surrounding tissues, and as a complication after operations to remove the primary tumor focus).

- Individual features of the intestinal structure (dolichosigma, mobile cecum, additional pockets and folds of the peritoneum),

- Hernias of the anterior abdominal wall and internal hernias.

Mechanical (obstructive) intestinal obstruction can also occur due to compression of the intestine by an external tumor or narrowing of the intestinal lumen as a result of inflammation. It is important to know that mechanical intestinal obstruction can develop not only with intestinal tumors, but also with cancers of other locations, for example, kidney cancer, liver cancer, bladder cancer, and uterine cancer.

Paralytic ileus can be the result of trauma, peritonitis, or significant metabolic disorders, such as low potassium levels in the blood. In cancer patients, paralytic intestinal obstruction may be caused by decompensation of liver and kidney function, impaired carbohydrate metabolism in the presence of concomitant diseases such as diabetes mellitus and a number of other conditions.

Spastic intestinal obstruction develops with lesions of the brain or spinal cord, poisoning with salts of heavy metals (for example, lead) and some other conditions. [9,10]

Preparation and performance of the operation

Before the operation begins, the patient must undergo instrumental diagnostics and radiography, and pass all the necessary tests. During a planned admission, three days before surgery, it is necessary to exclude foods that increase gas formation in the body. Eating and drinking liquids is prohibited 10 hours before surgery.

The first stage of the intervention is dissection of the adhesions between the intestine and the abdominal wall. In this way, the necessary space for surgical procedures is freed up. The adhesive junctions between the intestine and the abdominal wall are cut with sharp scissors (cold view). Next, the surgeon, after examining the small intestine, restores patency along its entire length.

At the end of the process, anti-adhesive barriers are installed, which reduce the possibility of the formation of repeated adhesions after surgery for abdominal adhesive disease.

Signs of intestinal obstruction

An early and obligatory symptom of acute intestinal obstruction is abdominal pain. The pain can occur suddenly without any warning signs, be “cramping”, and usually it does not depend on food intake. At first, attacks of pain during acute intestinal obstruction are repeated at approximately equal intervals and are associated with the physiological wave-like movement of the intestine - peristalsis. After some time, abdominal pain may become constant.

With strangulation obstruction, the pain is immediately constant, with periods of intensification during a wave of peristalsis. In this case, the subsidence of pain should be regarded as an alarm signal, since it indicates the cessation of intestinal peristaltic activity and the occurrence of intestinal paresis (paralysis).

With paralytic intestinal obstruction, abdominal pain is often dull, bursting.

Symptoms vary depending on the height of the food obstruction - in the esophagus, stomach, duodenum or large intestine. Retention of stool, including its absence for several hours, and lack of passage of gases are early symptoms of low intestinal obstruction.

When mechanical compression, paresis or narrowing is located in the area of the upper intestines, mainly at the onset of the disease, with partial patency of the intestinal tube, under the influence of therapeutic measures, the patient may have a bowel movement due to bowel movement located below the obstacle. Nausea and vomiting are often observed sometimes repeated, indomitable, increasing with increasing intoxication.

Sometimes there is bloody discharge from the anus.

Upon careful examination, you can notice significant bloating and pronounced asymmetry of the abdomen, peristalsis of the intestines visible to the eye, which then gradually fades away - “noise at the beginning, silence at the end.”

General intoxication, weakness, loss of appetite, apathy - these symptoms are observed in most patients with gradual progression of intestinal obstruction from partial to complete. [1,2]

Conservative treatment

Sometimes you can do without surgery. Typically, conservative treatment of intestinal obstruction involves the following measures:

- A nasogastric tube is inserted into the stomach through the nose to allow fluid to drain.

- Water-salt solutions are administered intravenously.

- Painkillers, antiemetics, and medications to improve the functioning of the intestines and other internal organs are prescribed.

- The patient's condition is constantly monitored.

If these measures do not help and the patient’s condition worsens, surgical treatment is resorted to. Conservative therapy is possible only in certain cases, with certain types of intestinal obstruction. Most often, cancer requires surgery.

Why is intestinal obstruction dangerous?

Intestinal obstruction leads to dehydration of the body, pronounced shifts in the water-electrolyte and acid-base balance of the body. It is based on a violation of food intake, its digestion and absorption, as well as the cessation of secretion of gastric and intestinal juices into the lumen of the gastrointestinal tract.

Since the tissues and cells of the body are sensitive to the slightest changes in the chemical constancy of the internal environment, such changes cause dysfunction of almost all organs and systems. Along with fluid and electrolytes, in case of intestinal failure, due to fasting, vomiting, and the formation of inflammatory exudate, a significant amount of proteins is lost (up to 300 g/day), especially albumin, which plays an important role in homeostasis. The presence of metastases in the liver, which inhibit the protein-synthetic function of the liver, further reduces the level of protein in the blood, reduces the oncotic pressure of the blood plasma, which causes the development of persistent edema.

The general intoxication of the body with the gradual development of intestinal obstruction is further worsened by the fact that in the contents of the afferent intestine, processes of decomposition and rotting begin, pathogenic microflora begins to multiply in the contents of the intestinal lumen, and toxic products accumulate. At the same time, physiological barriers that normally prevent the absorption of toxins from the intestines do not work and a significant part of toxic products enters the bloodstream, aggravating the general intoxication of the body. Necrosis (necrosis) begins to develop in the intestinal wall, the result of which is purulent peritonitis due to the spillage of intestinal contents into the peritoneal cavity. In this case, toxic products of tissue breakdown, microbial toxins, and severe metabolic changes can lead to sepsis and multiple organ failure and death of the patient. [5.11]

What needs to be done to save a person with intestinal obstruction?

The development of intestinal obstruction is an indication for urgent hospitalization in a surgical hospital, where the following is immediately performed:

- abdominal radiography,

- ultrasound examination of the abdominal organs

- irrigography is an x-ray examination with a contrast barium suspension introduced into the intestines using an enema.

In our clinic, we often use liquid contrast to better contour the bowel and to prevent barium from entering the peritoneal cavity during subsequent surgery. If the diagnosis is confirmed and/or severe clinical symptoms of peritonitis are present, emergency surgery is performed after very short preoperative preparation.

In the absence of symptoms of peritoneal irritation (peritonitis), conservative therapy is carried out for some time (up to a day) under the supervision of a surgeon:

- rehydration,

- administration of protein solutions, electrolytes,

- administration of antibiotics,

- release of the upper parts of the digestive tract by tube gastric lavage,

- intestinal lavage,

- pain relief, etc.

If there is no effect from conservative treatment, it is necessary to perform surgery as planned. If it is possible to remove the cause of obstruction, a diagnostic laparotomy with intestinal resection is performed. During the operation, an inspection of the abdominal cavity is required to clarify the cause of the development of acute intestinal obstruction and determine the total scope of the operation. [2]

If adhesions, volvulus, loop nodes, or invaginations are detected during an audit of the abdominal organs, they are eliminated. If possible, cytoreductive surgery is performed to remove the primary tumor focus that caused the development of acute intestinal obstruction.

According to existing rules, removal of the intestine in case of obstruction should be carried out at a certain distance above and below the site of obstruction (obstruction). If the diameter of the connected segments is not significantly different, an “end to end” anastomosis is performed; if there is a significant difference in the diameters of the adducting and efferent sections of the anastomosis, a “side to side” anastomosis is performed. In our clinic, we use both classic hand-suturing techniques for the formation of anostoses, and modern stitching devices such as staplers.

In case of severe general condition of the patient or the impossibility of forming a primary anastomosis for other reasons, for example, due to an advanced tumor process, the formation of a “tumor shell”, a large extent of the section of resected intestine, accumulation of a large volume of fluid in the abdominal cavity (ascites), on the anterior abdominal A hole is formed in the wall - a colostomy, into which the adducting and efferent segments of the intestine are brought out - a “double-barrel stoma”.

Depending on the section of the intestine from which the colostomy is formed, this surgical intervention has a different name:

- ileostomy - when removing the small intestine,

- cecostoma - blind,

- ascendo-, descendo- and transversostomy - respectively, ascending, transverse and descending sections of the transverse colon,

- with sigmostomy - from the sigmoid colon.

During surgery on the sigmoid colon, called the “Hartmann operation,” the efferent segment of the colon is always sutured tightly and immersed in the abdominal cavity. [2.12]

Acute adhesive intestinal obstruction is one of the most dangerous diseases of the abdominal organs, and the operation must be performed within 2 hours after the indications for it were given. Very often, the decision on the need for emergency intervention is made by the surgeon on duty at night or on holidays, when there are no more experienced colleagues nearby. All responsibility for the patient’s life falls on the shoulders of sometimes a young doctor, who is obliged to independently perform a complex operation. It is possible to get out of such a situation with honor only by strictly observing the tactical guidelines and techniques developed over many years by doctors involved in emergency abdominal surgery. This publication contains a description of the basic surgical techniques that allow achieving good results in the treatment of patients with acute adhesive intestinal obstruction.

Surgical access.

In most cases, with acute adhesive intestinal obstruction, the operation is performed through a wide incision in the anterior abdominal wall. According to strict indications, in the absence of multiple adhesions, the operation can be performed laparoscopically.

Before surgery, if possible, an ultrasound examination should be performed to determine where the intestinal loops are fixed to the anterior abdominal wall by adhesions. The laparoscopic version of the operation without preliminary ultrasound examination is unacceptable.

The optimal surgical approach is midline laparotomy. If necessary, access is expanded up or down. If there is a scar in the midline from a previous operation, the skin scar is excised using border incisions. Encapsulated ligatures of non-absorbable suture material are often found in the scar tissue of the linea alba, which are removed. Sometimes there are granulomas in the area of the ligatures, which should be excised along with the surrounding granulation tissue, and the bed should be treated with an antiseptic solution.

The parietal peritoneum in the area of the postoperative scar of the abdominal wall always has rough fusion with the aponeurosis of the white line of the abdomen. Moreover, as a rule, the greater omentum and intestinal loops are fixed to the parietal peritoneum by adhesions. In this regard, when dissecting a single block of tissue of the aponeurosis of the white line of the abdomen and the parietal peritoneum, it is possible to open the lumen of the intestine fixed to the parietal peritoneum. If before the operation it was not possible to perform an ultrasound examination and obtain information about the localization of visceroparietal adhesions, the following technique is used to reduce the risk of opening the intestinal lumen.

The laparotomy incision is extended 3-5 cm above or below the old surgical scar. The abdominal cavity is opened at the very top or bottom of the incision, outside the area of previous access, where the likelihood of tight fixation of the greater omentum and intestine is less.

After it has been possible to open the abdominal cavity, even if only for a short distance in the corner of the wound, further dissection of the single layer of aponeurosis and parietal peritoneum is significantly facilitated. By lifting the abdominal wall with a hook or Mikulicz clamps placed on the edge of the aponeurosis, the organs fixed with adhesions are separated from the parietal peritoneum in a sharp way, freeing up space for subsequent dissection of the aponeurosis with the peritoneum. In this way, the aponeurosis and parietal peritoneum are gradually dissected along the entire length of the laparotomy wound. If there is effusion in the abdominal cavity, it must be taken for microbiological examination.

The main landmark of the site of obstruction is the border between the afferent part of the intestine, which is overstretched with contents, and the collapsed intestinal loops of the efferent part. If the dilated adductor loops smoothly pass into the non-dilated part, this indicates the absence of mechanical intestinal obstruction, i.e. the surgeon is dealing with paralytic ileus.

Technique for separating adhesions.

The separation of “loose” adhesions, which are more often encountered with early adhesive intestinal obstruction, does not present any technical difficulties. These adhesions can be destroyed with a finger, without applying excessive force, leading to damage to the serous lining of the intestine, or cut with scissors. When cutting adhesions with scissors, the technique of “reverse work” of the cutting parts of the instrument is used. To do this, the tips of the closed branches are inserted between the welded organs, after which the branches are moved apart, which makes it possible to designate a “layer” between the fixed loops of the intestine. Due to the lack of vascularization of adhesions, bleeding does not occur. Cord-like adhesions, usually of sufficient length, are cut with scissors or an electric knife. When using electrocoagulation to separate adhesions, you should strictly ensure that there is no burn to the intestinal wall. To do this, the thermal effect zone must be at least 3-5 mm from the intestinal wall.

The greatest technical difficulties arise in cases where the intestinal loops are tightly fixed to each other or to the parietal peritoneum over a large area, forming a single conglomerate. There are situations in which the fixation of intestinal loops among themselves is so tight that it is impossible to identify the boundary between them or the parietal peritoneum. When the intestinal wall is tightly fused with the parietal peritoneum, the safest method is to separate the intestine by excision of the adjacent peritoneum.

To separate dense planar interintestinal adhesions, you need to resort to the following technique. In the place of the least pronounced adhesions, a channel is created towards the posterior abdominal wall. The index finger of the right hand is inserted into the resulting space and, using pendulum-like movements, without applying excessive force, the adhesions are separated along the posterior surface of the intestinal conglomerate. As a rule, adhesions and their density in this area are not so pronounced, due to which it becomes possible to partially separate the intestinal loops along the posterior surface of the conglomerate. After the intestinal loops achieve some mobility, they are rotated anteriorly and in this position the separation of adhesions is completed. If it is not possible to separate the intestinal conglomerate, and the level of obstruction falls on this part of the intestine, then two options are possible. If there are no signs of impaired viability of the deformed part of the intestine, a bypass interintestinal anastomosis is performed. In case of circulatory disorders, resection of the intestinal conglomerate is performed.

When adhesions are separated, superficial damage to the intestinal wall may occur. Overstretched adductor loops are more often damaged. In cases where the damage affects not only the serous, but also the muscular layer (in this case, the intact intestinal mucosa prolapses through the wall defect), it is necessary to apply seromuscular sutures with absorbable suture material on an atraumatic needle 4/0 or 5/0. Superficial slit-like injuries The serous cover should not be sutured, since after emptying the overstretched intestine, the edges of these defects are compared independently.

When the intestinal lumen is opened, the wall defect is immediately clamped with a gauze swab to stop the release of intestinal contents. Strict adherence to asepsis is a necessary measure, since the microflora populating the lumen of the afferent loop is always highly virulent and if the abdominal cavity is contaminated, there is a real threat of infectious postoperative complications.

Before suturing the intestinal wall defect, the damaged loop must be completely isolated from the adhesions. Suturing intestine that is not mobilized from adhesions is never successful.

The mobilized damaged intestine is isolated from the abdominal cavity with gauze swabs. Soft intestinal sponges are applied to the intestine above and below the injury. The hand with the tampon covering the perforation hole is removed. The intestinal contents remaining in the lumen of the intestinal loop isolated by intestinal sphincter are aspirated by suction, and the perforation zone and adjacent tissues are treated with an antiseptic solution. After this, the hole is sutured in the transverse direction in 2 rows of sutures with absorbable suture material on an atraumatic needle 4/0-5/0.

Having identified the site of obstruction, they cross the commissure that compresses the intestinal lumen and its mesentery in case of strangulation obstruction, and separate the planar adhesions that deform the intestinal loops in case of obstructive obstruction.

Once the intestinal obstruction has been resolved, intestinal viability must be assessed. With strangulation obstruction, the greatest circulatory disturbances always occur in the area of the strangulation groove. An absolute sign of necrosis of the intestinal wall is its dirty gray or black-green color in combination with a significant decrease in tissue turgor (flabbiness of the intestinal wall with areas of its retraction with a collapsed intestine or prolapse of individual areas with increased intestinal pressure) and an unpleasant specific odor. Doubts about the viability of the intestine should arise if the affected area does not peristalt, has a purplish-black color, and the pulsation of the mesenteric and direct arteries of the intestinal wall is not detected. In such a situation, after cutting the adhesions, the intestinal loop is immersed in the abdominal cavity and left for 15-20 minutes. During this time, hemostasis is carried out, nasointestinal intubation is performed and intestinal contents are aspirated. The compromised part of the intestine is then examined again.

A more aggressive way to test the viability of the intestine is to warm it with gauze swabs soaked in hot saline. If these measures do not lead to a change in the condition of the intestinal wall, the intestine is considered non-viable, which serves as an indication for its resection. In turn, bowel resection requires preliminary nasointestinal intubation.

Nasointestinal intubation

, providing decompression of the small intestine, helps normalize blood circulation in the intestinal wall and quickly restore motor activity. Accordingly, the indications for it are expansion of the intestinal lumen to 5 cm or more, loss of motor activity (paralytic intestinal obstruction), as well as the need to perform resection of the small intestine.

Nasointestinal intubation is performed together with an anesthesiologist, who inserts a special multi-perforated probe about 1.5 m long through the nose into the stomach. When the probe is passed through the esophagus, it can curl up in the latter without reaching the stomach. In this case, under the control of a laryngoscope, an endotracheal tube No. 8 is inserted into the esophagus and a nasointestinal probe is passed through its lumen, which, after intubation is completed, is transferred from the mouth to the nasal passage, as with posterior nasal tamponade.

After the head of the probe is in the stomach, it is necessary to pass it into the duodenum. To do this, the surgeon fixes the pylorus with his left hand, and with his right hand passes the head of the probe into the duodenal bulb through its lumen. Next, the probe is advanced through the duodenum by displacing it through the wall of the stomach. With the typical arrangement of all parts of the duodenum, this can be done quite simply and quickly. If there are sharp bends in the intestine, the following techniques are used to insert the probe. The probe head is held in the duodenal bulb with the left hand and shifted into the vertical part of the duodenum, while with the right hand, under the mesentery of the transverse colon, the head is directed into the lower horizontal part of the duodenum. A probe inserted into this area, as a rule, easily extends beyond the ligament of Treitz into the jejunum. If an obstacle is felt in the area of the duodenojejunal junction, which is due to the presence of adhesive deformation in the form of a double-barreled shotgun, the olive of the probe is moved with the right hand in the desired direction or the adhesions that deform the intestine are dissected. Forced advancement of the probe if there is a perceived obstruction in the area of the duodenojejunal junction is unacceptable due to the danger of perforation of the intestinal wall.

Once the probe head passes the ligament of Treitz, the easiest stage begins - passing the probe through the small intestine. Intubation of the small intestine is accelerated if the operating surgeon advances the probe in its initial section with both hands, and the assistant guides the head of the probe and helps its advancement, straightening the intestinal loops. The procedure for inserting the probe can be complicated due to the formation of redundant loops of the probe in the stomach, which occurs if the entry of the probe into the stomach is ahead of its progress through the small intestine, therefore the actions of the surgeon and the anesthesiologist advancing the probe into the stomach must be synchronous. Intubation is completed when the ileocecal portion of the intestine is reached. After this, intestinal contents are aspirated.

A probe should not be inserted into the cecum to avoid reflux of colonic contents into the small intestine, which inevitably leads to additional colonization of the small intestine with fecal microflora. Aspiration of intestinal contents is carried out only after completion of intubation, since passing the probe through the inflated loops is less traumatic and takes less time.

Having completed intubation of the small intestine, control the placement of the probe. It should not have loops or deformations. “Wringing” of the probe at any side hole negates the effectiveness of decompression in the postoperative period.

An important detail in the correct position of the probe in the intestine is the location of the last side hole, which should be in the middle part of the stomach. Displacement of the last opening into the esophagus is unacceptable, as this can lead to aspiration of gastric contents into the respiratory tract in the postoperative period. A less dangerous mistake is inserting the last lateral opening into the duodenum. In this case, patients may experience vomiting, since the stomach cavity is undrained. To make it easier to determine the location of the last hole in the probe, a ring is created at this level from a narrow strip of plaster. By palpating the thickening on the probe through the wall, one can accurately determine its correct location.

If it is necessary to perform intestinal resection, a nasointestinal probe is passed distal to the resected area, and the intestinal contents are aspirated. Then the probe is moved proximal to the resected part and only after that they begin resection of the intestine, and after completing the latter, the probe is again moved distal to the interintestinal anastomosis.

Resection of necrotic small intestine should be performed within the limits of viable tissue so that circulatory disturbances in the area of intestinal intersection are minimal. To achieve this, they retreat from the visible zone of necrosis by 20-30 cm. Since microcirculatory changes in the afferent loop of the intestine are always more pronounced than in the efferent loop, it is necessary to retreat a greater distance in the oral direction.

After bowel resection, anastomosis of the stumps can be performed either end to end or side to side. The last option for anastomosis is used when there is a pronounced discrepancy between the diameters of the afferent and efferent intestinal stumps.

During anastomosis, end-to-end stumps of the small intestine, previously stitched with staplers or tied with ligatures, are freed from fatty tissue in the mesentery area for no more than 8-10 mm. Seromuscular stay sutures are placed on opposite sides of the intestinal stumps at the level of the border of the mobilized mesentery. By pulling in opposite directions using these sutures, the intestine is stretched to the diameter of the ectatic stump of the afferent loop. Using absorbable suture material on atraumatic needles, the first row of interrupted seromuscular sutures is applied to form the posterior lip of the anastomosis. In this case, there should be a free edge of the wall 6-8 mm long for applying an internal row of sutures with a 3/0 or 4/0 monofilament absorbable thread. The last ones are to pierce the intestinal wall without capturing the mucous membrane - the needle is punctured through the submucosal layer. The front row of sutures is applied in compliance with the same technical rules. The mesenteric defect is sutured using interrupted sutures under anastomosis. In this case, the sutures are applied superficially so that the mesenteric vessels do not get into them.

If there is a pronounced discrepancy between the diameters of the afferent and efferent loops of the intestine, the anastomosis must be performed side to side. Intestinal stumps stitched with stitching devices are peritonized by applying purse-string or interrupted sutures. Interrupted sutures are used for severe infiltration of the intestinal wall or its large diameter. The first row of interrupted atraumatic seromuscular sutures is placed along the mesenteric edge of the intestines for 3-4 cm. In this case, the length of the “blind” pockets in the stump area should not exceed 1-2 cm. The intestinal wall is cut with an electrocoagulator, retreating 6-8 mm from the first row of seams. The length of the incision should be no more than 2-2.5 cm. The intestinal lumen is treated with an antiseptic solution. An internal row of monofilament absorbable sutures is placed without grasping the mucous membrane on the posterior lip of the anastomosis. Then the anterior lip of the anastomosis is formed in a similar way.

Regardless of the method of anastomosis, the nasointestinal probe is inserted 30-50 cm beyond the anastomosis.

When completing the operation, the transudate formed in the abdominal cavity during the operation and the blood released from the dissected adhesions are aspirated. If necessary, additional hemostasis is performed. The abdominal cavity is drained through a counter-aperture with a tube that is installed in the pelvic cavity.

The laparotomy wound is sutured tightly in layers using absorbable suture material.

Laparoscopic operations for acute adhesive intestinal obstruction

The laparoscopic version of the operation is only valid if the surgeon is fluent in the necessary technical skills of laparoscopic surgery (experience in independent operations - cholecystectomy, appendectomy, fundoplication - must exceed more than 100 interventions). The resolution of the laparoscopic surgical technique is limited by the severity of adhesions. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis is possible only if the patient has not previously had multiple operations and, according to the results of ultrasound examination, there are no multiple adhesions. Overestimation of indications for laparoscopic surgery carries the risk of severe complications.

The Veress needle for applying pneumoperitoneum and the first trocar are inserted into the abdominal cavity in the projection of the “acoustic window” (a section of the anterior abdominal wall free from intestinal loops fixed by adhesions), established during ultrasound examination. The trocar stylet is replaced with a laparoscope. Diagnostic laparoscopy is performed, during which the prevalence of adhesions and the condition of the intestine are assessed. Already at this stage it is often possible to identify the intestine compressed by the adhesions. If the affected area of the intestine is not accessible to direct inspection, the search should be carried out by moving the collapsed intestinal loops with a Babcock forceps. Violation of this rule—displacement of overstretched loops located above the site of obstruction with instruments—is more traumatic and can lead to opening of the intestinal lumen. The details of the adhesiolysis technique are identical to those in the traditional version of the operation. If the intestinal lumen is opened (and it almost always happens above the level of the obstacle), a significant amount of intestinal contents with highly virulent microflora enters the abdominal cavity. Laparoscopic sanitation of the abdominal cavity in such a situation cannot be adequate, so laparotomy should be performed immediately.

The presented essay is based on personal experience of 40 years of surgical practice and does not claim to be the ultimate truth. However, by observing surgeons adhering to the stated recommendations, we were able to verify their competence. The “small” details of technology offered often allow you to avoid big problems.

Is stoma removal always necessary during surgery for intestinal obstruction?

In addition to creating a stoma, an alternative way to restore the passage of food through the intestines is to create an intestinal bypass anastomosis. Operations are named after the parts of the intestine connected, for example:

- An operation on the right side of the large intestine is called a bypass ileotransverse anastomosis.

- The imposition of an anastomosis between the initial part of the small intestine and the final part of the jejunum is called a bypass ileojejunostomy.

Each of these interventions can be temporary, performed to prepare the patient for subsequent stages, or final if radical surgery is not possible.

The main task solved during surgical treatment of acute intestinal obstruction is to save the patient’s life from the threat of breakthrough of intestinal contents into the peritoneal cavity with the development of acute peritonitis and death of the patient.[3,6]

What happens to the removed stoma?

Within 2-3 weeks after the operation for acute intestinal obstruction, provided the general condition improves and the consequences of intoxication of the body are eliminated, a repeat operation can be performed to restore the natural passage of food. In such cases, an intestinal anastomosis is performed, which is immersed inside the abdominal cavity.

In other cases, a colostomy bag is attached to the colostomy to collect intestinal contents. Modern types of colostomy bags make it possible to maintain an acceptable quality of life even when used for several months. [2.6]

Postoperative period and possible complications

Typically, patients who have had surgery for intestinal obstruction can return to normal eating within a few days. In the first days, nutrition is provided intravenously; you are only allowed to moisten your lips with a damp piece of cloth. Many people experience severe postoperative pain, so it is important to prescribe adequate pain relief.

The risk of complications depends on the extent of the operation, the patient's general health and other factors:

- Failure of intestinal sutures is a life-threatening complication and requires immediate reoperation. If the sutures do not perform their function well, intestinal contents enter the abdominal cavity and peritonitis develops.

- Heavy bleeding is also dangerous and requires surgery.

- A common complication is the formation of blood clots in the vessels of the legs. To prevent it, drugs are prescribed that reduce blood clotting, elastic bandages are applied to the legs, and the patient is tried to return to active movements as quickly as possible.

- To prevent infection, antibiotics are prescribed intravenously through drainage tubes that are left in the abdominal cavity after surgery.

- If during the operation the doctor made a large incision, the sutures may heal poorly and come apart. The risk of this complication is higher in elderly, frail patients suffering from concomitant diseases.

- Any operation is a trauma for the body. After it, adhesions can form in the abdomen, and they can again lead to intestinal obstruction.

Is it possible to help a patient without surgery?

Often in severe cases and inoperable tumors in critically ill patients with partial intestinal obstruction, decompression of the gastrointestinal tract is achieved by endoscopic placement of a stent in the colon. In this case, the surgical operation is performed through the natural lumen of the intestine - under the control of a colonoscope, a balloon is initially inserted into the lumen of the colon per rectum, expanding the narrowed (stenotic) area, and then a stent is installed.

Timely preventive installation of a stent in the intestinal lumen can prolong life and significantly improve its quality by reducing intoxication, as well as avoid possible surgical intervention in patients with stage 4 cancer. Stenting of areas of the duodenum can be performed in a similar manner. [9,11]

We install stents in the large intestine in patients with intestinal cancer and with a high class of anesthetic risk due to the presence of concomitant diseases, including coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus and a number of others. This will allow you to maintain intestinal patency for a long time and avoid surgical intervention.

Book a consultation 24 hours a day

+7+7+78

Bibliography:

- Clinical recommendations: Acute intestinal obstruction of tumor etiology. - Moscow, 2014.

- Clinical recommendations: Acute intestinal obstruction of tumor etiology in adults. — Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. — 2022.

- Intestinal obstruction: educational and methodological manual / P. S. Neverov K46 [and others]. – Minsk: BSMU, 2022. – 42 p.

- Surgical diseases. Educational and methodological manual / Edited by Chernyadyev S.A. – Ekaterinburg, 2019. –29s.

- B. O. Kabeshev, S. L. Zyblev. Acute intestinal obstruction. — A practical guide for doctors. — Gomel, 2022.

- M.Yu. Kabanov, I.A. Solovyov, O.V. Balura. — Results of complex treatment of patients with acute intestinal obstruction of carcinomatous origin. - Bulletin of the Russian Military Medical Academy, 1(37)-2012.

- International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) https://mkb-10.com/.

- Barnett A, Cedar A, Siddiqui F, et al. Colorectal cancer emergencies. J Gastrointest Cancer 2013;44(2):132–42.

- National clinical guidelines “acute non-tumor intestinal obstruction”. — Russian Society of Surgeons. — 2015.

- Karakaş DÖ, Yeşiltaş M, Gökçek M, Eğin S, Hot S. Etiology, management, and survival of acute mechanical bowel obstruction: Five-year results of a training and research hospital in Turkey. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2019;25:268-280.

- Colorectal cancer (update): evidence review for effectiveness of stenting compared with emergency surgery for acute large bowel obstruction. Developed by the National Guideline Alliance part of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. FINAL (January 2020).

- Subramaniyan Ramanathan, Vijayanadh Ojili, Ravi Vassa, and Arpit Nagar. Large Bowel Obstruction in the Emergency Department: Imaging Spectrum of Common and Uncommon Causes. J Clin Imaging Sci. 2017; 7: 15. doi: 10.4103/jcis.JCIS_6_17