From this article you will learn:

- Physiology of intestinal motility

- Symptoms of intestinal motility disorders

- Causes of weak intestinal motility

- Foods that stimulate intestinal motility

- Exercises to improve intestinal motility

- Positive effect of hydrogen water on intestinal motility

- Criteria for choosing a device for producing hydrogen water

Intestinal motility plays a big role in how well food is absorbed and unnecessary elements are eliminated from the body. If it is weakened, a person may experience not only constipation, but also other unpleasant symptoms, ranging from fatigue and headaches to skin rashes and fever.

To prevent this from happening, you should keep your intestines in working order, since the daily load on it is high (modern man eats a lot today). Below we have described in detail the reasons for the dysfunction of this organ, and also given a list of products and exercises for home gymnastics that are designed to help and improve its motor skills.

Physiology of intestinal motility

So, intestinal motility - what is it? Motility, or peristalsis, of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is the process of coordinated contractions of its smooth muscles, which are represented by a set of longitudinal and circular muscle fibers.

This process begins with a piece of food entering the mouth. Chewing and swallowing lead to the launch of the digestive system, which includes gastrointestinal peristalsis. When a bolus of food enters the intestine, its smooth muscles are stretched, the response to which is their contraction. The coordinated work of the intestinal muscles leads to the fact that its contents and digestive juices are mixed and moved to the lower sections of the gastrointestinal tract for final processing with the subsequent removal from the body of those residues that have not been digested.

Peristalsis is complemented by rhythmic segmentation, tonic muscle contractions, pendulum-like and propulsive movements of the intestine, which together are called motility.

A person does not control intestinal motility; the process occurs reflexively. The strength and frequency of contractions of the intestinal muscles depend on the autonomic nervous system, which regulates the functioning of the internal organs. Its parasympathetic part affects peristalsis, which consequently increases, and signals from the sympathetic nervous system lead to the fact that the motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract weakens.

Physiology of intestinal motility

It normally takes 1-3 days to complete the complete digestion process, with the greatest time being devoted to the movement of food masses in the large intestine.

Only after a two to three hour period does food enter the small intestine. That is, it takes about a day to fill the colon and remove undigested food debris out. If peristalsis is impaired, then this process slows down or accelerates, that is, it is either poor or increased intestinal motility.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF MOTOR DISORDERS OF THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

The paper describes major gastrointestinal motility impairments predisposing to various gastroenterological diseases. It shows their diagnostic methods and current approaches to drug therapy.

A.A. Sheptulin, prof., Department of Propaedeutics of Internal Diseases, Moscow Medical Academy named after. THEM. Sechenov Prof. AA Sheptulin, Department of Internal Propedeutics, IM Sechenov Moscow Medical Academy

IN

Currently, in gastroenterology, much attention is paid to disorders of the motor function of the digestive tract.

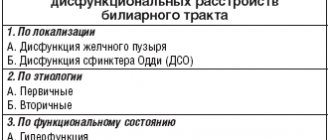

This is due to the fact that, as studies in recent years have shown, certain motility disorders of the gastrointestinal tract can be the leading pathogenetic factor contributing to the development of many common gastroenterological diseases. This group of diseases with primary disorders of motility of the digestive tract includes gastroesophageal reflux disease and various dyskinesias of the esophagus (diffuse and segmental esophagospasm, cardiospasm), functional dyspepsia and dyskinesia of the duodenum, biliary tract and sphincter of Oddi, irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- this term refers to all cases of pathological reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus - is one of the most common diseases in the clinic of internal medicine. Its symptoms (primarily heartburn), with varying degrees of severity, are detected in 20 - 40% of the total population. Reflux esophagitis (a particular manifestation of gastroesophageal reflux disease, when inflammatory changes in the mucous membrane of the distal esophagus occur) is found in 6 - 12% of people who undergo endoscopic examination of the upper gastrointestinal tract. The clinical significance of gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis is determined, firstly, by the possibility of their severe course with the formation of peptic ulcers and peptic stricture of the esophagus, the occurrence of esophageal-gastric bleeding, the progression of structural changes (gastric and intestinal metaplasia) of the epithelium of the esophageal mucosa with the outcome in the so-called Barrett's esophagus, the development of which significantly increases the risk of developing esophageal cancer [1].

see also

Serious clinical problems also arise from “extraesophageal manifestations” of gastroesophageal reflux disease, which include the addition of repeated pneumonia, chronic bronchitis, reflux laryngitis and pharyngitis, and dental damage. Currently, a special form of bronchial asthma has been identified, which is pathogenetically associated with gastrointestinal reflux. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can lead to extrasystole and other heart rhythm disturbances. Finally, it is well known that reflux esophagitis, as well as various esophageal dyskinesias (primarily esophagospasm) are a common cause of chest pain not associated with heart disease. Sometimes such painful sensations are incorrectly interpreted as angina pain, which entails not entirely correct drug therapy. The occurrence of gastroesophageal reflux disease is caused by impaired motility of the esophagus and stomach. The main factors predisposing to its development are a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, an increase in intragastric pressure, and a weakening of “esophageal clearance” (the ability of the esophagus to remove contents that have entered it back into the stomach). Functional (non-ulcer) dyspepsia

is a symptom complex that includes complaints of pain in the epigastric region, a feeling of heaviness and fullness in the epigastrium after eating, early satiety, nausea, vomiting, belching, heartburn, regurgitation, etc., in which a thorough examination fails to identify the presence of such organic diseases such as peptic ulcer, reflux esophagitis, stomach cancer, etc. Functional dyspepsia is also a common disease and occurs in 10 - 15% of people in the population [2]. Depending on the predominance of certain clinical symptoms, 4 variants of functional dyspepsia are distinguished. With the ulcer-like variant, night and “hungry” pains in the epigastric region are noted, which disappear after eating. The reflux-like variant is characterized by heartburn and the presence of burning pain in the area of the xiphoid process of the sternum. With the dyskinetic variant, heaviness and a feeling of fullness in the epigastric region after eating, and early satiety are observed. With a nonspecific version of the patient’s complaint, it can be difficult to unambiguously assign to one group or another. The occurrence of functional dyspepsia is also largely associated with the presence of motor disorders of the stomach and duodenum. In patients with a reflux-like variant, a decrease in the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter is often detected; with the ulcer-like variant, there is a high frequency of duodenogastric reflux; with the dyskinetic variant, a decrease in the tone of the stomach and a weakening of its evacuation function are detected.

| Irritable bowel syndrome is defined as a complex of functional disorders, the main clinical manifestations of which are abdominal pain (usually relieved after defecation), accompanied by flatulence, rumbling, a feeling of incomplete bowel movement or an urgent urge to defecate, constipation, diarrhea, or their alternation. Irritable bowel syndrome is perhaps the most common gastroenterological disease. According to various sources, its frequency among the entire population ranges from 14-22 to 30% and higher [3]. |

Depending on the leading clinical symptom, there are currently 3 main clinical variants of irritable bowel syndrome: with a predominance of diarrhea, with a predominance of constipation, and a variant that occurs predominantly with pain and

see also

flatulence. The appearance of these symptoms is also caused by impaired motility of the small and large intestine. According to modern concepts, in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, the nervous regulation of intestinal motor function is impaired. Due to the increased sensitivity of the receptors of the intestinal wall to stretching, pain and discomfort occur in such patients at a lower threshold of excitability than in healthy people. The practical significance of irritable bowel syndrome is also determined by the fact that the nature of the patient’s intestinal disorders that are not always correctly understood and their interpretation as a manifestation of a serious organic disease sometimes leads to unnecessary repetition of various instrumental studies and the prescription of enhanced drug therapy, which often turns out to be ineffective. In addition to diseases with primary disorders of motility of the gastrointestinal tract, there are also so-called secondary disorders of motility of the digestive tract, which arise against the background of other diseases and which doctors of various specialties often encounter in their practice. These disorders include, in particular, post-vagotomy disorders, disorders of gastric and intestinal motility that occur in patients with diabetes mellitus (due to diabetic neuropathy), disorders of the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract that appear in patients with systemic scleroderma as a result of the proliferation of connective tissue in the wall of the esophagus, stomach and intestines, impaired motility of the digestive tract in certain endocrine diseases (thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism), etc.

Diagnostics

To identify certain disorders of the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract, many different instrumental diagnostic methods are currently used [4]. The oldest of them is the x-ray method

, which, however, is now in very limited use.

This is due to the fact that studying the motor function of any part of the digestive tract requires a certain time, while the duration of the patient’s stay behind the X-ray screen is strictly limited. The scintigraphic method

involves the patient receiving food labeled with radioactive isotopes of technetium or indium.

Subsequent recording of sensor readings allows one to draw a conclusion about the rate of food evacuation from the stomach. The ultrasound method

is currently becoming increasingly widespread in the study of motility of the digestive tract.

The use of special ultrasonographic techniques makes it possible to assess the nature of gastric evacuation and the contractility of the gallbladder. The manometric method

is carried out technically using balloon kymography or open catheter techniques.

It makes it possible to determine the tone of various parts of the gastrointestinal tract (for example, pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter or sphincter of Oddi). Registration of the electrical activity of muscle cells allows us to draw a conclusion about the state of tone and peristalsis of certain parts of the digestive system. This is the basis for the methods of electrogastrography and electromyography,

with the help of which, in particular, the tone of the stomach and anal sphincter is determined.

has now become widespread in clinical practice .

Each episode of gastroesophageal reflux is accompanied by a drop in normal pH values in the lumen of the esophagus (5.5 - 7) below 4. By monitoring intraesophageal pH levels for 24 hours, it is possible to determine the total number of episodes of gastroesophageal reflux during the day (normally no more than 50) and their total duration (normally no more than 1 hour).

In addition, by comparing the pH-gram data with entries in the patient’s diary, in which he records the time of eating, the onset and disappearance of pain, taking medications, etc., it is possible to determine whether the patient’s pain in the epigastric region or region heart with the presence of gastroesophageal reflux at this moment. A promising method for studying intestinal motor function is

+

breath test ,

based on the determination of H+ in exhaled air after preliminary intake of lactulose labeled with this isotope. After ingestion, lactulose begins to break down only in the cecum. Therefore, by the time that passes from the moment of taking labeled lactulose until the appearance of H+ in the exhaled air, one can judge the duration of the oral-cecal transit.

Treatment

Drug therapy for diseases accompanied by weakening of the tone and peristalsis of various parts of the gastrointestinal tract (gastroesophageal reflux disease and reflux esophagitis, reflux-like and dyskinetic variants of functional dyspepsia, hypomotor dyskinesia of the duodenum and biliary tract, hypomotor variant of irritable bowel syndrome, etc.), includes includes the use of drugs that enhance the motility of the digestive tract. Medicines prescribed for this purpose (these drugs are called prokinetics) exert their effect either by stimulating cholinergic receptors (carbacholin, cholinesterase inhibitors) or by blocking dopamine receptors. Attempts to use the prokinetic properties of the antibiotic erythromycin, which have been made in recent years, are faced with a high frequency of side effects due to the main (antibacterial) activity of the drug, and remain at the stage of experimental research. Also, studies of the prokinetic activity of other groups of drugs have not yet gone beyond the scope of experimental work: 5-HT3 receptor antagonists (tropisetron, ondansetron), somatostatin and its synthetic analogues (octreotide), cholecystokinin antagonists (asperlicin, loxiglumide), kappa receptor agonists (fedotocin ) and others [5]. As for carbacholin and cholinesterase inhibitors, due to the systemic nature of their cholinergic action (increased saliva production, increased secretion of hydrochloric acid, bronchospasm), these drugs are also used relatively rarely in modern clinical practice. remained the only drug from the group of dopamine receptor blockers for a long time .

Experience with its use has shown, however, that the prokinetic properties of metoclopramide are combined with its central side effect (the development of ectrapyramidal reactions) and a hyperprolactinemic effect, leading to the occurrence of galactorrhea and amenorrhea, as well as gynecomastia.

Domperidone

is also a dopamine receptor blocker, however, unlike metoclopramide, it does not cross the blood-brain barrier and thus does not cause central side effects.

The pharmacodynamic effect of domperidone is associated with its blocking effect on peripheral dopamine receptors localized in the wall of the stomach and duodenum. Domperidone increases the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, enhances the contractility of the stomach, improves the coordination of contractions of the antrum of the stomach and duodenum, and prevents the occurrence of duodenogastric reflux. Domperidone is currently one of the main drugs for the treatment of functional dyspepsia. Its effectiveness in this disease was confirmed by data from large multicenter studies conducted in Germany, Japan and other countries [6]. In addition, the drug can be used to treat patients with reflux esophagitis, patients with secondary gastroparesis resulting from diabetes mellitus, systemic scleroderma, and also after gastric surgery. Domperidone is prescribed in a dose of 10 mg 3-4 times a day before meals. Side effects with its use (usually headache, general weakness) are rare, and extrapyramidal disorders and endocrine effects occur only in isolated cases. Cisapride,

which is now widely used as a prokinetic drug, differs significantly in its mechanism of action from other drugs that stimulate the motor function of the gastrointestinal tract.

The exact mechanisms of action of cisapride remained unclear for a long time, although they were assumed to be realized through the cholinergic system. In recent years, it has been shown that cisapride promotes the release of acetylcholine due to the activation of a recently discovered new type of serotonin receptors (5-HT4 receptors) localized in the neuronal plexuses of the muscular lining of the esophagus, stomach, and intestines. Cisapride has a pronounced stimulating effect on esophageal motility, increasing, to a greater extent than metoclopramide, the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and significantly reducing the total number of episodes of gastroesophageal reflux and their total duration. In addition, cisapride also potentiates propulsive motility of the esophagus, thus improving esophageal clearance. Cisapride enhances the contractile activity of the stomach and duodenum, improves gastric emptying, reduces duodenogastric bile reflux and normalizes antroduodenal coordination. Cisapride stimulates the contractile function of the gallbladder, and, by enhancing the motility of the small and large intestines, accelerates the passage of intestinal contents. Cisapride is currently one of the main drugs used in the treatment of patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease [7]. In the initial and moderate stages of reflux esophagitis, ukzapride can be prescribed as monotherapy, and in severe forms of mucosal damage - in combination with antisecretory drugs (H2 blockers or proton pump blockers) [8]. Currently, experience has been accumulated in long-term maintenance administration of cisapride to prevent relapses of the disease. Multicenter and meta-analytic studies have confirmed good results from the use of cisapride in the treatment of patients with functional dyspepsia. In addition, the drug proved effective in the treatment of patients with idiopathic, diabetic and post-vagotomy gastroparesis, patients with dyspeptic disorders, duodenogastric reflux and sphincter of Oddi dysfunction that arose after cholecystectomy. Cisapride gives a good clinical effect in the treatment of patients with irritable bowel syndrome, which occurs with a picture of persistent constipation, resistant to therapy with other drugs, as well as patients with intestinal pseudo-obstruction syndrome (developing, in particular, against the background of diabetic neuropathy, systemic scleroderma, muscular dystrophy and etc.). Cisapride is prescribed in a dose of 5 - 10 mg 3 - 4 times a day before meals. The drug is usually well tolerated by patients. The most common side effect is diarrhea, occurring in 3–11% of patients, which usually does not require discontinuation of treatment. If patients have signs of increased motility in certain parts of the digestive tract, drugs with an antispasmodic mechanism of action are prescribed. Traditionally, in our country, myotropic antispasmodics are used for this purpose: papaverine, no-shpa, halidor. Abroad, in similar situations, preference is given to butylscopolamine,

an anticholinergic drug with antispasmodic activity exceeding that of myotropic antispasmodics.

Butylscopolamine is used for various types of esophagospasm, hypermotor forms of duodenal and biliary dyskinesia, irritable bowel syndrome, which occurs with the clinical picture of intestinal colic. The drug is prescribed in a dose of 10 - 20 mg 3 - 4 times a day. Side effects characteristic of all anticholinergic drugs (tachycardia, decreased blood pressure, accommodation disorders) are expressed during treatment with butylscopolamine to a much lesser extent than with atropine therapy, and occur mainly with its parenteral use. For manifestations of esophagospasm, a certain clinical effect can be achieved by the use of nitrates (for example, nitrosorbide) and calcium channel blockers (nifedipine), which have a moderate antispasmodic effect on the walls of the esophagus and the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. For hypermotor variants of irritable bowel syndrome, so-called functional diarrhea, which, unlike organic (for example, infectious) diarrhea, is observed mainly in the morning, is associated with psycho-emotional factors and is not accompanied by pathological changes in stool tests, the drug of choice is loperamide.

By binding to opiate receptors in the colon, loperamide inhibits the release of acetylcholine and prostaglandins in the colon wall and reduces its peristaltic activity. The dose of loperamide is selected individually and is (depending on stool consistency) from 1 to 6 capsules of 2 mg per day. Thus, as data from numerous studies show, motility disorders of various parts of the digestive tract are an important pathogenetic factor in many gastroenterological diseases and often determine their clinical picture. Timely detection of motor disorders of the gastrointestinal tract using special instrumental diagnostic methods and the use of adequate drugs that normalize gastrointestinal motility can significantly improve the results of treatment of such patients.

Literature:

1. Kahrilas PJ. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. JAMA 1996;276:983-8. 2. Talley NJ. Dyspepsia and functional dyspepsia. Motility 1992;20:4-8. 3. Heaton KW. Irritable bowel syndrome. Recent Advances in Gastroenterology (Ed. R. Pounder). Edinburgh 1992:49-62. 4. Smouth AJPM, Akkermans LMA. Normal and disturbed motility of the gastrointestinal tract. Petersfield 1992:1-313. 5. Debinski HS, Kamm MA. New treatments for neuromuscular disorders of the gastrointestinal tract. Gastrointestinal J Club 1994;2:2-11. 6. Brogden RN, Carmine AA, Heel RC, Speight TM, Avery GS. Domperidone. A review of its pharmacological activity, pharmacokinetics and therapeutic efficacy in the symptomatic treatment of chronic dyspepsia and as antiemetic. Drugs 1982;24:360-400. 7. Physiological long-term treatment of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. New perspectives with cisapride (Proceedings of symposium). J Drug Dev 1993;5:1-28. 8. Tytgat GNJ, Janssens J, Reynolds J, Wienbeck M. Update on the pathophysiology and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: the role of prokinetic therapy. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 1996;8:603-11.

Symptoms of intestinal motility disorders

Not only obvious unpleasant phenomena can indicate diseases of the digestive tract and that intestinal motility is impaired. Symptoms of the existence of the disease can have different manifestations:

- headache;

- chronic fatigue;

- weight gain;

- frequent bowel movements;

- rashes;

- interruptions in sleep;

- intestinal obstruction;

- increase in body temperature.

Three studies that will help stop aging

Such a simple element as water has always been considered vital and necessary.

But at the same time, the number of myths about water, scientific facts and opinions that are imposed every day and then refuted, encourages us to look for answers to our questions. To help you, my team and I have prepared a webinar and a gift: 3 unique materials based on the experience of our experts on prolonging youth with the help of water. After completing our free webinar you will learn:

Artyom Khachatryan

practicing physician-nutritionist, naturopath

Immediately after registration you will receive a selection of studies:

Aging: you can't stop it, you can't accept it

What conclusions did 21st century scientists come to when studying water and its ability to prolong youth?

In fact, we don't know anything about water.

Important information for prolonging youth that we could have been told back in school

Hydrogen water is the most powerful natural remedy for prolonging youth

Why hydrogen-enriched water is considered the most effective, safe and affordable way to prolong youth

Find out how water can take care of your health, youth and beauty at a free webinar by nutritionist Artyom Khachatryan!

The causes of these symptoms may be toxins that accumulate in the intestines due to the fact that it has poor patency or, conversely, due to unnaturally frequent bowel movements. Failure to promptly treat with drugs or other means can result in decreased motor function, general nutritional deficiencies, and the spread of toxins into the bloodstream.

Motility disorders of the esophagus and stomach

print version- home

- >

- For patients

- >

- Doctors' advice

- >

- Proceedings of the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases

Where can I get tested?

| If treatment doesn't help | Popular about gastrointestinal diseases | Stomach acidity |

On the website GastroScan.ru in the Literature section there is a subsection “Popular Gastroenterology”, containing publications for patients on various aspects of gastroenterology.

William E. Whitehead, professor of medicine and professor of psychology

Motility disorders of the esophagus and stomach

The International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders (IFFGD) has prepared a range of resources for patients and their families regarding functional gastrointestinal disorders. This article is devoted to disorders caused by abnormal motility of the gastrointestinal tract (GERD, dysphagia, functional chest pain, gastroparesis, dyspepsia and others) and their characteristic symptoms, such as difficulty swallowing, chest pain, heartburn, nausea and vomiting. Motility and functioning of the gastrointestinal tract are normal

. The term motility is used to describe muscle contractions in the gastrointestinal tract. Although the gastrointestinal tract is a round tube, when its muscles contract, they block this tube or make its internal lumen smaller. These muscles can contract synchronously, moving food in a certain direction - usually downwards, but sometimes up short distances. This is called peristalsis. Some contractions may push the contents of the digestive tube forward. In other cases, the muscles contract more or less independently of each other, mixing the contents but not moving them up or down the digestive tract. Both types of contractions are called motility. The gastrointestinal tract is divided into four sections: the esophagus, stomach, small intestine and large intestine. They are separated from each other by special muscles called sphincters, which regulate the flow of food from one section to another and which are tightly closed most of the time. Each section of the gastrointestinal tract performs different functions in the overall digestive process and therefore each section has its own types of contractions and sensitivities. Contractions and sensitivity that do not correspond to the functions performed by this department can cause various unpleasant symptoms in the patient. This article describes the normal contractions and sensitivity of the esophagus and stomach, and the symptoms that may occur as a result of abnormalities.

Esophagus

Normal motor skills and functions

.

The function of the esophagus is to transport food from the mouth to the stomach. To accomplish this task, each swallow is accompanied by powerful, synchronized (peristaltic) contractions. The esophagus usually does not contract between swallows. The sphincter muscles that separate the esophagus from the stomach (called the lower esophageal sphincter, or LES) usually remain tightly closed, preventing acid from the stomach from flowing into the esophagus. However, when we swallow, this sphincter opens (relaxes) and the food we swallow enters the stomach. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

.

The most common symptom of GERD is heartburn, which occurs when gastroesophageal reflux causes acid from the stomach to periodically back up into the esophagus and irritate the lining of the esophagus. This occurs when the lower esophageal sphincter, which separates the stomach from the esophagus, does not work properly. The main function of this sphincter is to prevent reflux from contracting the stomach. The causes of this reflux may be: weak sphincter muscles, too frequent spontaneous relaxation of the sphincter, hiatal hernia. In a hiatal hernia, the stomach extends partially up into the chest above the muscle that separates the abdomen from the chest (this muscle is called the diaphragm). A hiatal hernia weakens the lower esophageal sphincter. Gastroesophageal reflux disease can be diagnosed on an outpatient basis through a test called intragastric pH testing,

which records the rate at which acid flows into the esophagus (reflux rate).

To do this, a small, soft tube with one or two sensors is inserted through the nose into the esophagus. It connects to a battery-powered computing unit. To study the effects of acid on the esophagus, recordings are made over a period of 18–24 hours. All this time, the patient lives in his usual mode and is engaged in daily activities. Also used are endoscopy, which looks at the esophagus using a thin fiberoptic tube, and esophageal manometry

, which measures the pressure in the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter to determine whether they are functioning properly.

Dysphagia.

Dysphagia is a condition in which there are problems with swallowing.

This can happen if the muscles in the tongue and neck that push food down the esophagus do not work properly due to a stroke or other condition that affects the nerves or muscles. Food may also be retained because the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax enough to allow it to enter the stomach (a disorder called achalasia

) or because the muscles of the esophagus contract inappropriately (

esophageal spasm

).

Dysphagia can cause backflow of food into the esophagus and vomiting. There may also be a sensation of something stuck in the esophagus or pain. The diagnostic test for dysphagia is esophageal manometry

, in which a small tube with pressure sensors is inserted through the nose into the esophagus and is used to detect and record contractions of the esophagus and relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter.

The duration of such a study is approximately 30 minutes. Functional chest pain

.

Sometimes patients experience chest pain that is different from heartburn (no burning sensation), and it can be confused with pain of cardiac origin. The doctor always finds out whether the patient has heart problems, especially if the patient is over 50 years old, but in many cases he does not find such problems. Many patients with chest pain do not have heart disease; the pain arises either from spasmodic contractions of the esophagus, from increased sensitivity of the nerve endings in the esophagus, or from a combination of muscle spasms and increased sensitivity. The diagnostic test that is done in this case is esophageal manometry, described above. To ensure that gastroesophageal reflux is not the cause of chest pain, ambulatory 24-hour pH testing

of the esophagus is performed.

Stomach

Normal motor skills and functions

. One of the functions of the stomach is to grind food and mix it with digestive juices so that when the food reaches the small intestine it is absorbed. The stomach usually moves its contents into the intestines at a controlled rate. There are three types of contractions in the stomach:

- Peristaltic contractions of the lower part of the stomach, creating waves of food particles mixed to varying degrees with gastric juice. They occur when the pyloric sphincter is closed. The purpose of these contractions is to crush pieces of food, the frequency of these contractions is 3 times per minute.

- Slow contractions of the upper stomach, lasting a minute or more, that follow each swallow and which allow food to enter the stomach; in other cases, slow contractions occur in the upper part of the stomach to help empty the stomach.

- Very strong, synchronized random contractions occur between meals, when digested food has already left the stomach. They are accompanied by the opening of the pyloric sphincter and are “cleansing waves”, their function is to remove any indigestible particles from the stomach. In the physiology of digestion, they are called the “migrating motor complex.”

Delayed gastric emptying (gastroparesis)

. Symptoms of gastroparesis include nausea and vomiting. Poor gastric emptying can occur for the following reasons:

- The outlet of the stomach (the pylorus) may be blocked by an ulcer, tumor, or something swallowed and undigested.

- The pyloric sphincter at the exit of the stomach does not open enough or at the right time to allow food to pass through it. This sphincter is controlled by neurological reflexes that ensure that only very small particles leave the stomach and that not too much acid or sugar comes out of the stomach, which could irritate or injure the small intestine. These reflexes depend on nerves, which are sometimes damaged.

- The peristaltic, three-minute contractions of the lower stomach may become out of sync and stop moving stomach contents toward the pyloric sphincter. It usually also has a neurological basis, the most common cause being long-term diabetes mellitus, but in many patients the cause of delayed gastric emptying is unknown and they are diagnosed idiopathic

(that is, unknown cause)

gastroparesis

.

Tests ordered for patients with gastroparesis usually include endoscopy, which looks at the inside of the stomach, and radioisotope gastric emptying rate testing, which measures how quickly food leaves the stomach. The radioisotope gastric emptying rate test relies on the patient eating food to which radioactive substances have been added, so the rate of gastric emptying can be measured by a device such as a Geiger counter (gamma camera). Another less commonly used test is electrogastrography

, which measures very small electrical currents in the stomach muscles and determines whether the patient has three-minute contractions in the lower part of the stomach.

Contractions of the stomach muscles can also be measured by a tube with pressure sensors inserted into the patient's stomach through the nose ( antroduodenal manometry

).

Functional dyspepsia.

Many patients experience pain or discomfort that is felt in the center of the abdomen above the navel.

Examples of discomfort that are not painful: stomach fullness, early satiety (a feeling of fullness in the stomach immediately after starting to eat), bloating, nausea. There is no single motility disorder that explains all of these symptoms, but about a third of patients with these symptoms have gastroparesis (usually not so severe as to cause frequent vomiting), and about a third have problems relaxing the upper part of the stomach after swallowing food (stomach accommodation disorder in response to food intake). About half of patients with these symptoms are overly sensitive and experience stomach discomfort and fullness, even when only a small amount of food has entered the stomach. Gastric emptying studies (see above) can show whether there are problems with gastric emptying. Other motility disorders are more difficult to detect, but scientists have developed a device called a barostat

,

which includes a computer-controlled pump that helps determine how adequately the upper stomach relaxes during meals and how much food in the stomach causes it. pain or discomfort.

Conclusion

The gastrointestinal tract consists of four sections separated by sphincter muscles. These four sections perform different functions and have different types of muscle contractions to perform these functions. One such section is the esophagus, which transports food to the stomach, where it is mixed with digestive enzymes and converted into a more or less liquid form. Abnormal motility or sensation in any part of the gastrointestinal tract can cause characteristic symptoms such as food impaction, pain, heartburn, nausea and vomiting. To determine how adequate the motility of each part of the gastrointestinal tract is, certain studies are performed, based on the results of which general practitioners, gastroenterologists or surgeons make decisions regarding the best treatment option. ________________________________________________________________________________ The views of the authors do not necessarily reflect the position of the International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Diseases (IFFGD).

IFFGD does not warrant or endorse any product in this publication or any claims made by the author and does not accept any liability regarding such matters. This article is not intended to replace consultation with a physician. We recommend visiting a doctor if your health problem requires an expert opinion. Back to section

| Diagnosis of gastrointestinal diseases | Symptoms of gastrointestinal diseases | Advice from doctors in the USA, Russia, etc. | Heartburn and GERD |

Causes of weak intestinal motility

Motility of the intestines and stomach depends on many factors. These are the nature and diet, level of physical activity, psycho-emotional status, general health and diseases that can affect the entire functioning of the digestive system. These factors cause peristalsis to work faster or slower, which can ultimately cause either diarrhea or constipation.

Causes of slow intestinal motility leading to constipation:

- low consumption of foods that contain fiber (vegetables, fruits, herbs, coarse cereals and products made from wholemeal flour);

- insufficient amount of fluid consumed, which leads to a decrease in the volume of intestinal contents and insufficient stimulation of its muscles;

- restriction in food when following a diet, which leads to a decrease in the amount of food taken, and constant snacking, when a lot of food is unnoticed in small portions;

- a sedentary lifestyle and lack of physical activity and, as a result, a decrease in muscle tone of the anterior abdominal wall;

- negative emotions: worries, fears, anxiety, stress;

- chronic diseases;

- taking medications.

How to Guaranteed Lose Weight with Water: 3 Simple Habits

There are almost no women in the world who have never been on a diet. Sooner or later, everyone faces the desire to lose a couple of kilograms.

In order for the treasured number to appear on the scales sooner, introduce 3 healthy and super simple habits into your life: we have prepared a document with experts where we describe them in detail.

How to Guaranteed Lose Weight with Water: 3 Simple Habits

Artyom Khachataryan

Practitioner, nutritionist, naturopath

75% of our course participants who follow these habits have significantly reduced their weight!

You can download the document for free:

PDF: 2 MB

Also, increased intestinal motility and diarrhea are possible with changes in diet, poisoning (including alcohol, infectious and drug), food allergies, psycho-emotional overload, chronic fatigue and chronic stress, ultimately leading to the development of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

How peristalsis disorders reduce quality of life

Parents of children with functional gastroenterological disorders observe every day how much the pathology worsens the child’s quality of life. For example, the most common disease of this type is irritable bowel syndrome, which is constant abdominal pain, diarrhea and/or constipation.

Children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), gastroparesis and intestinal pseudo-obstruction suffer from:

- difficulty swallowing,

- heartburn,

- unexplained chest pain,

- chronic vomiting,

- bloating,

- loss of weight or appetite,

- problems with eating,

- constipation,

- fecal incontinence or clotting,

- arching of the back (in infants).

This is an additional stress factor and further enhances the child’s social maladjustment. Often, parents unsuccessfully take their children to doctors for years and resort to symptomatic treatment of the manifestations of the disease (heartburn, constipation, diarrhea) because they cannot eliminate the cause itself.

Foods that stimulate intestinal motility

To improve intestinal motility, you need to eat healthy foods. In this case, you need to eat, dividing meals throughout the day little by little. Intestinal motility worsens when fasting or dieting. An increase in diarrhea and constipation can cause dangerous diseases.

Therefore, it is necessary to contact doctors who will determine the type of optimal nutrition specifically for you and choose the intestinal motility regulators that suit you. You also need to remember that if bowel movements occur less than once in three days, then this is constipation.

What to do and how to make intestinal motility work with the help of food?

1. Fiber . Products rich in fiber are not broken down in the gastrointestinal tract, but become a source of nutrition for intestinal bacteria, absorb and retain water, which normalizes stool consistency.

Fiber-rich foods include:

- Most vegetables, especially beets and cabbage, are not cooked.

- Fruits and berries such as apricots, apples, pears, kiwis and blackberries.

- Greenery.

- Products containing whole grain flour or wholemeal flour.

- Dried fruits (pay attention to dried apricots, prunes, dates and figs).

- Long-cooked cereals: buckwheat, oatmeal, millet, pearl barley and barley.

- Nuts such as almonds, unsalted peanuts, pistachios.

- Legumes.

It is recommended to consume 100-150 g of foods rich in fiber twice or even three times a day.

This is interesting!

“Leaky Gut Syndrome: 6 Ways to Solve the Problem” Read more

2. Organic acids contained in sour milk, yogurt, kefir, sour fruits and berries.

3. Sweet foods that contain simple carbohydrates. Give preference to honey, marshmallows, marshmallows, marmalade, caramel, preserves and jams, sweeteners (sorbitol and fructose).

4. Salty foods , such as marinades and pickles (it is advisable not to overuse salt, no more than 12-15 g per day).

5. Cold food and drinks.

6. Mineral water with gas (carbon dioxide) : take cold, 1-1.5 hours before meals, on an empty stomach.

In the absence of contraindications from the kidneys or heart, it is recommended to drink up to 1.5-2 liters of water per day.

Thus, the normalization of intestinal motility obliges us to follow a diet in which food intake is carried out 5-6 times a day.

Newspaper "News of Medicine and Pharmacy" Gastroenterology (323) 2010 (thematic issue)

The motor function of the digestive tract is an important component of the digestive process, ensuring the capture of food, its mechanical processing (grinding, mixing) and movement along the digestive tract in strict accordance with the periods of chemical processing of food products in its departments. Chewing, the act of swallowing and the movement of a bolus of food in the upper part of the esophagus are carried out with the participation of striated muscles. In the remaining parts of the digestive tract, motor activity is performed by smooth muscles. Contractions of the smooth muscles of the stomach wall carry out the motor function of the organ. It ensures the deposition of ingested food in the stomach, its mixing with gastric juice in the area adjacent to the gastric mucosa, the movement of gastric contents to the outlet into the intestine and, finally, the portioned evacuation of gastric contents into the duodenum. The reservoir, or depositing, function of the stomach is combined with the digestive function itself and is carried out mainly in the body and fundus of the stomach; the role of the pyloric part is especially important in the evacuation function.

The muscles of the stomach are characterized by tonic and periodic, phasic contractions. Tonic contractions ensure good contact of the chyme with its walls, and periodic contractions promote mixing (tonic waves and gastric peristalsis, pendular contractions and rhythmic segmentation of the intestine) and movement of contents along the digestive tract. The transition of contents from the stomach to the duodenum is also determined by the state of the pyloric sphincter.

Regulation of the motor function of the digestive tract is carried out by neurohumoral mechanisms. Activation of the vagus nerve enhances esophageal peristalsis and gastric motor activity, while sympathetic fibers have the opposite effect. The intraorgan part of the autonomic nervous system (Auerbach's plexus) is of great importance in the regulation of gastric motility due to local peripheral reflexes. Excitatory reflexes include esophageal-intestinal and gastrointestinal. Gastrin, histamine, serotonin, motilin, insulin, and potassium ions have an exciting effect on the contractile activity of the smooth muscles of the stomach.

Inhibition of gastric motility is caused by enterogastron, adrenaline, norepinephrine, secretin, glucagon, cholecystokinin-pancreozymin, vasoactive intestinal peptide, bulbogastron. Mechanical irritation of the intestine by food substances leads to reflex inhibition of the motor activity of the stomach (enterogastric reflex). This reflex is especially pronounced when fat and hydrochloric acid enter the duodenum.

Impaired motility can be a leading pathogenetic factor contributing to the development of many common diseases of the digestive tract. The group of diseases with primary dysfunction of the motor function of the upper digestive tract includes: gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), various esophageal dyskinesias (diffuse and segmental esophagospasm, cardiospasm), functional dyspepsia.

In addition to diseases with primary disorders, there are so-called secondary disorders of motility of the digestive tract, which arise against the background of other diseases and which therapists often encounter in their practice. These violations include, in particular:

- disorders of gastric and intestinal motility that occur in patients with diabetes (due to diabetic neuropathy, which leads to dysfunction of the autonomic nervous system); - post-vagotomy disorders (crossing the trunk of the vagus nerve usually increases the tone of the proximal parts of the stomach and at the same time reduces the phasic activity of the distal parts; the consequence of this is accelerated evacuation of fluid and slow evacuation of solid food from the stomach); — disorders of the motor function of the digestive tract in patients with systemic scleroderma as a result of the proliferation of connective tissue in the wall of the esophagus, stomach and intestines; - primary damage to the muscles of the stomach - observed with polymyositis and dermatomyositis; — disturbances in motility of the digestive tract in certain endocrine diseases (thyrotoxicosis, hypothyroidism), etc.

The main reasons for delayed gastric emptying:

- functional dyspepsia (dysmotor variant); - acid-dependent diseases (peptic ulcers, GERD); - gastritis (atrophic gastritis, antral gastritis type B); - acute viral gastroenteritis; - mechanical causes (stomach cancer, prepyloric, pyloric, duodenal ulcers, idiopathic hypertrophic stenosis); - metabolic and endocrine disorders (diabetic gastroparesis, hypothyroidism, uremia, hyperkalemia, hypercalcemia); - consequences of surgical treatment of gastric diseases; - neurological disorders (diseases of the central nervous system, spinal cord, Parkinson's disease); - medications (anticholinergics, opiates, L-dopa, tricyclic antidepressants, somatostatin, cholecystokinin, aluminum hydroxide, progesterone), high doses of alcohol, nicotine; — pseudo-obstruction (chronic, secondary to amyloidosis, dermatomyositis); - systemic scleroderma; — idiopathic (gastric dysrhythmia, desynchronosis); - heavy physical activity.

The main reasons for accelerating gastric emptying:

- Zollinger-Ellison syndrome; — consequences of surgical treatment of stomach diseases (dumping syndrome, vagotomy + pyloroplasty (antrumectomy)); - medications (erythromycin, cisapride, metoclopramide, domperidone, beta-blockers); - light physical exercise.

Clinical manifestations of delayed gastric emptying:

- feeling of heaviness and fullness in the epigastrium after eating; - epigastric pain ± heartburn; - nausea and vomiting; - feeling of quick satiety; - drowsiness after eating; - belching and regurgitation; - weight loss.

Clinical manifestations of accelerated gastric emptying:

- epigastric pain; - nausea; - spasmodic pain in the abdomen; - diarrhea; - symptoms of hypoglycemia; - symptoms of hypovolemia.

GERD is a disease associated with impaired motor function of the upper digestive tract, pathological reflux of stomach contents into the esophagus.

The main motor dysfunctions that are important in the pathological physiology of GERD are:

- decreased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and its transient relaxation; - weakening of esophageal clearance (the ability of the esophagus to remove contents that have entered it back into the stomach); - slower gastric emptying.

Clinical manifestations of GERD:

- heartburn; - belching sour; - pain (burning) in the epigastric region.

They often occur after eating, when bending the body forward or in a horizontal position, and stop or decrease after taking soda or antacids.

Dysphagia and odynophagia are less common.

Extraesophageal manifestations of GERD are common and intensively studied:

1) dental manifestations (caries, periodontitis, drooling, halitosis); 2) oropharyngeal manifestations (nasopharyngitis, pharyngitis, sensation of a lump in the throat); 3) otolaryngological manifestations (laryngitis and other lesions of the larynx, otalgia, otitis media, rhinitis); 4) bronchopulmonary manifestations (chronic recurrent bronchitis, bronchiectasis, aspiration pneumonia, hemoptysis, paroxysmal cough, bronchial asthma); 5) chest pain: a) associated with cardiac dysfunction (reflux reduces coronary blood flow, provokes angina attacks and heart rhythm disturbances); b) is directly related to the effect of reflux on the esophagus; 6) gastric manifestations (the leading pathogenetic factor is increased intragastric pressure, the clinical picture is dominated by complaints from the stomach).

Achalasia of the cardia of the esophagus is a chronic neuromuscular disease, the development of which is associated with damage to the intramural nerve plexus of the esophagus, as a result of which the consistent peristaltic activity of the esophageal wall is disrupted and there is no relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter in response to a swallow (swallowing). This is most likely due to a deficiency of inhibitory mediators, primarily nitric oxide (NO). As a result, an obstacle appears in the path of the food bolus in the form of an unrelaxed sphincter, and food enters the stomach only when the esophagus is additionally filled with liquid, when the weight of its column exerts a mechanical effect on the lower esophageal sphincter.

Clinical symptoms of achalasia of the cardiac part of the esophagus:

- dysphagia; - pain behind the sternum; - regurgitation (belching, regurgitation); - esophageal vomiting; - loss of body weight; - hypovitaminosis.

Symptoms appear or intensify with neuro-emotional stress. In some cases, symptoms decrease after drinking liquid in one gulp.

Functional dyspepsia (FD) is a complex of functional disorders that last more than 3 months over a 12-month period and include symptoms of dyspepsia (pain or discomfort strictly in the epigastrium, associated or not associated with food intake, a feeling of fullness in the epigastrium after eating, early satiety, nausea , belching, heartburn), not associated with intestinal dysfunction, in which a thorough examination of the patient fails to identify any other organic causes of dyspepsia (peptic ulcers, reflux esophagitis, stomach cancer). One of the main pathophysiological components of FD, especially its dysmotor variant, is impaired motility of the upper digestive tract. At the same time, the myoelectric activity (brady-, tachygastria) of contractility changes (a decrease in the number of peristaltic waves in the antrum of the stomach and a decrease in their amplitude). According to scintigraphy and ultrasonography, this leads to impaired gastric emptying.

Diagnostics

Modern methods for assessing the motor-evacuation function of the esophagus

1. X-ray examination - there is a violation of the passage of barium suspension from the esophagus to the stomach, the presence of a large amount of contents in the esophagus on an empty stomach, dilatation of the esophagus, the gas bubble of the stomach is not detected.

2. Esophagomanometry allows you to determine the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter and identify the lack of relaxation during swallowing (with GERD).

3 Intraesophageal pH monitoring (traditional probe method or probeless pH recording system using a Bravo radiocapsule) - for GERD in order to determine the total time during which the pH level drops below 4, the number of refluxes per day, the duration of the longest reflux.

Modern methods for assessing the motor-evacuation function of the stomach

1. X-ray (only the time of initial and final evacuation is assessed, the impossibility of repeated multiple studies, low accuracy (barium is not a “food product”)).

2. Ultrasound method (the rate of gastric emptying is determined, but mainly the evacuation of liquid food is determined, the method is unsuitable for patients after gastric surgery, depends on the experience of the operator).

3. Epigastric impedance (the results are clearly influenced by the location of the electrodes, unsuitable for patients after gastric surgery, acid hypersecretion or duodenogastric reflux cause measurement errors).

4. Scintigraphy of the stomach with 99Tc or 111In (after the patient has eaten food labeled with radioactive isotopes, registration of sensor indicators allows us to draw a conclusion about the rate of evacuation of food from the stomach. Does not allow for a quantitative assessment of the transpyloric intake of food, radiation exposure to the patient, the process of preparing the food mixture is difficult for testing).

5. Video endoscopic capsule (study of gastroduodenal motility).

6. Breath test with 13C-octanoic acid.

13C breathing tests to study the motor-evacuation function of the stomach

1. 13C-bicarbonate breath test - to study the evacuation of liquid and semi-liquid food from the stomach.

2. 13C-acetate breath test - to study the evacuation of liquid food from the stomach.

3. 13C2-glycine breath test - to study the evacuation of food from the stomach, as well as to study the metabolism of certain amino acids and proteins.

4. 13C-octane breath test - to study the rate of evacuation of solid food from the stomach. Allows you to determine the degree of impairment of the motor-evacuation function of the stomach, select the dose (single, daily and course) of prokinetics, monitor the effectiveness of treatment.

Treatment

A diet with a restriction of foods that relax the lower esophageal sphincter (tomatoes, coffee, strong tea, chocolate, animal fats, mint), irritants (onions, garlic, seasonings), and gas-forming foods (peas, beans, champagne, beer). It is necessary to avoid the consumption of alcohol, very spicy, hot or cold foods and carbonated drinks. Patients should avoid overeating, eat regularly, and should not eat 2–3 hours before bedtime.

Patients with GERD are recommended to include foods high in protein into their diet: low-fat milk, cheese, cottage cheese, boiled meat. The fact is that protein foods have buffering properties, that is, they are able to bind acid, as a result of which the pH of the gastric contents increases and the pressure in the area of the lower esophageal sphincter increases. That is, both the aggressiveness of the refluxate and the likelihood of reflux itself decreases.

Medicines that affect tone and motor skills

M-cholinergic receptor blockers:

— atropine sulfate — 0.1–0.6 mg IM; - scopolamine butyl bromide (buscopan, buscocin, spasmobrew) - 10-20 mg 3-5 times a day. orally (or rectally); - metacin - 2-4 mg 2-3 times a day. (in the table) or IM 1 mg 2-3 times a day.

Non-selective myotropic antispasmodics:

— drotaverine hydrochloride — 40–80 mg orally or intramuscularly 2–4 ml 1–3 times a day; - papaverine - 40-60 mg 3-5 times a day. i/m.

Prokinetics are drugs that can correct motility disorders of the digestive tract: they enhance the contractility of the esophagus, increase the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter and the motor activity of the stomach, normalize the phase relationship of the migrating motor complex, and improve coordination of the stomach and duodenum. Such pharmacological properties contribute to their widespread use both as a course of treatment and as symptomatic therapy on demand. For motility disorders of the upper digestive tract, prokinetics are used - dopamine receptor blockers:

- non-selective - metoclopramide; — selective first generation — domperidone; - selective II generation - itopride.

Prokinetics are the drugs of choice for the treatment of dysmotor FD. Monotherapy is carried out:

- domperidone - 10-20 mg 3 times a day. 15-30 minutes before meals for 2-4 weeks or with metoclopramide - 10 mg 3 times a day for 2 weeks.

First-line drugs for the treatment of GERD are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). After achieving remission, maintenance therapy with PPIs or histamine H2 receptor blockers is necessary.

- PPI: omeprazole 20–40 mg, or lansoprazole 30 mg, or rabeprazole 20 mg, or pantoprazole 40 mg, or esomeprazole 20–40 mg 1–2 times a day orally for 14–30 days.

— Histamine H2 receptor blockers: the most powerful antisecretory effect is famotidine 20 mg 1–2 times a day for 8–12 weeks until the endoscopic picture normalizes, followed by the use of maintenance doses — 10 mg for 2–3 months, which helps avoid recurrence of GERD.

— Peristalsis stimulants (prokinetics): domperidone or metoclopramide 10 mg 3–4 times a day 10–15 minutes before meals and before bedtime for 14–30 days; itopride 50 mg 3 times a day 15–30 minutes before meals for 14–21 days.

— Antacids on demand: aluminum phosphate (phosphalugel), aluminum hydroxide with magnesium hydroxide (almagel, maalox) 1 dose (20 g gel, or 1–2 tablets, or 15 ml suspension) 3–4 times a day every 1–1 .5 hours after meals and at night for no more than 14 days.

Treatment of achalasia of the cardial part of the esophagus

1. Antacids (aluminum hydroxide and/or magnesium hydroxide orally, 1 dose 30 minutes before meals) - on demand (if pain occurs).

2. Enveloping agents (bismuth subnitrate 0.5 g 30 minutes before meals, diluted in 30 ml of water) - as required.

Thus, disturbances in the motor function of the upper digestive tract are an important pathogenetic factor in many common diseases of the digestive tract and often determine their clinical picture. Timely detection of movement disorders using modern diagnostic methods and the use of adequate drugs that normalize motor skills can significantly improve the condition of patients.

Exercises to improve intestinal motility

If you are asking a question about how to improve intestinal and gastric motility, it means that you do not want to deal with problems with its functioning: diarrhea or constipation. At the same time, self-medication is not an option. It is important to remember that you cannot begin treatment for constipation until the cause of its occurrence is determined, since it can be either ordinary colitis or a duodenal ulcer, etc.

Exercises to improve intestinal motility

The most common cause of constipation is the presence of a sluggish, lazy intestine with slow peristalsis. In this case, it can be stimulated by using diet and exercise, which will train the muscles of the abdominal press, diaphragm and pelvic floor.

Remember, if you have an umbilical hernia, an intestinal or duodenal ulcer, pregnancy, high blood pressure, menstruation, then neither gymnastics nor self-massage can be done. It is also contraindicated with a full stomach: the minimum break after eating is 2 hours.

Intestinal gymnastics will delight you with its simplicity and ease, considering that half of the exercises can be performed without getting out of bed. Regular exercise is the key to success, since this will improve blood circulation in the abdominal organs, strengthen the abdominal muscles, and facilitate the passage of gases, which will help improve bowel function.

- Starting position (I.P.) - you need to lie on your back, bend your knees slightly and make a movement as if you were pedaling a bicycle. Repeat 30 times.

- I.P. – the same. Pull the legs that are bent, as in the first exercise, to the stomach with your hands and return to IP. Repeat 10 times.

- I.P. – the same. Raise both legs at the same time and try to bring them behind your head - repeat 10-15 times.

- I.P. – lie on your back, bend your knees. You need to bring your knees together and spread them 15–20 times.

- I.P. – get on your knees, rest your hands on the floor, do not bend your arms. The back should be parallel to the floor. Raise your legs alternately with your knees bent. Repeat 10 times for the left and right legs.

- I.P. - as in the fifth exercise. Take in air through your mouth and, exhaling, bend your lower back down and relax your stomach. Stay in this position for a short time. Return to I.P., gasp for air. Exhaling, pull in your stomach and arch your back upward, just like cats do. Repeat 20–30 times.

- I.P. – stand up straight with your arms at your sides. Exhale deeply, pulling in and out your stomach. Repeat 5-8 times. Thanks to this exercise, you will massage the internal organs and improve intestinal motility.

- You can finish the set of exercises by walking in one place, raising your knees high. Repeat for 2-3 minutes.

How else can you make your intestinal motility work? There are several ways to self-massage.

These methods are very easy to implement, you can easily cope with both:

- Lie on your back and relax. With your right hand lying on your stomach, make circular movements clockwise. Stroking should be done gently, not with sudden movements, avoiding pressure.

- Lie on your back. Using a hand massager, actively massage the arches of your feet.

Motor function of the colon

The motor function of the colon provides a reserve function, i.e., accumulation of intestinal contents and periodic removal of feces from the intestine. In addition, intestinal motor activity promotes water absorption. The following types of contractions are observed in the colon: peristaltic, antiperistaltic, propulsive, pendular, rhythmic segmentation. The outer longitudinal layer of muscles is located in the form of stripes and is in constant tone. Contractions of individual sections of the circular muscle layer form folds and swellings (haustra). Typically, waves of haustration move slowly through the colon. Three to four times a day, strong propulsive peristalsis occurs, which propels the intestinal contents in the distal direction.

Regulation of gastrointestinal motility

Regulation of the motor function of the digestive tract is carried out by neurohumoral mechanisms.

Activation of the vagus nerve enhances peristalsis of the esophagus and relaxes the tone of the gastric cardia. Sympathetic fibers have the opposite effect. In addition, the regulation of motor activity is carried out by the intermuscular, or Auerbach, plexus.

The vagus nerves stimulate the motor activity of the stomach, while the sympathetic nerves inhibit it. The intraorgan part of the autonomic nervous system (Auerbach's plexus) is of great importance in the regulation of gastric motility due to local peripheral reflexes. Gastrin, histamine, serotonin, motilin, insulin, and potassium ions have an exciting effect on the contractile activity of the smooth muscles of the stomach. Inhibition of gastric motility is caused by enterogastron, adrenaline, norepinephrine, secretin, glucagon, CCK-PZ, GIP, VIP, bulbogastron. Mechanical irritation of the intestine by food substances leads to reflex inhibition of the motor activity of the stomach (enterogastric reflex). This reflex is especially pronounced when fat and hydrochloric acid enter the duodenum.

The motor activity of the small intestine is regulated by myogenic, nervous and humoral mechanisms. Spontaneous motor activity of intestinal smooth muscles is due to their automaticity. There are two known “rhythm sensors” of intestinal contractions, one of which is located at the junction of the common bile duct into the duodenum, the other in the ileum. Organized phasic contractile activity of the intestinal wall is also carried out with the help of neurons of the Auerbach nerve plexus, which have rhythmic background activity. These mechanisms are influenced by the nervous system and humoral factors. Parasympathetic nerves primarily excite, while sympathetic nerves inhibit contractions of the small intestine. The effects of irritation of the autonomic nerves depend on the initial state of the muscles, frequency and strength of irritation.

Reflexes from various parts of the digestive tract, which can be divided into excitatory and inhibitory, are of great importance for the regulation of small intestinal motility. Excitatory reflexes include esophageal-intestinal, gastrointestinal and intestinal-intestinal, inhibitory reflexes include intestinal, rectoenteric, as well as receptor inhibition of the small intestine (receptor relaxation) during eating, which is then replaced by increased motility. The reflex arcs of these reflexes are closed both at the level of the intramural ganglia of the intraorgan division of the autonomic nervous system, and at the level of the nuclei of the vagus nerves in the medulla oblongata and in the nodes of the sympathetic nervous system. The motility of the small intestine depends on the physical and chemical properties of chyme. Rough food containing large amounts of fiber and fats stimulate the motor activity of the small intestine. Acids, alkalis, concentrated salt solutions, hydrolysis products, especially fats, enhance motility. Humoral substances regulate intestinal motility, either directly affecting myocytes or enteric neurons. Vasopressin, oxytocin, bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, gastrin, motilin, CCK-PZ, substance P stimulate motility; secretin, VIP, GIP inhibit.

Regulation of the motor activity of the colon is carried out primarily by the intraorgan division of the autonomic nervous system: the intramural nerve plexuses (Auerbach and Meissner). In stimulating the motor activity of the colon, reflexes play a significant role when irritating the receptors of the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and also the colon itself. Irritation of rectal receptors inhibits colon motility. Correction of local reflexes occurs by overlying ANS centers. Sympathetic nerve fibers passing through the splanchnic nerves inhibit motor activity; parasympathetic, which are part of the vagus and pelvic nerves, strengthen. Mechanical and chemical stimuli increase motor activity and accelerate the movement of chyme through the intestine. Therefore, the more fiber in the food, the more pronounced the motor activity of the colon. Serotonin, adrenaline, glucagon inhibit colon motility, cortisone stimulates it.

The act of defecation and its regulation

Feces are removed through the act of defecation, which is a complex reflex process of emptying the distal part of the colon through the anus. When the ampoule of the rectum is filled with feces and the pressure in it increases to 40 - 50 cm of water column. irritation of mechano- and baroreceptors occurs. The resulting impulses along the afferent fibers of the pelvic (parasympathetic) and pudendal (somatic) nerves are sent to the defecation center, which is located in the lumbar and sacral parts of the spinal cord (involuntary defecation center). From the spinal cord, along the efferent fibers of the pelvic nerve, impulses go to the internal sphincter, causing it to relax, and at the same time increasing the motility of the rectum.

The voluntary act of defecation is carried out with the participation of the cerebral cortex, hypothalamus and medulla oblongata, which exert their effect through the center of involuntary defecation in the spinal cord. From the alpha motor neurons of the sacral spinal cord, impulses travel through the somatic fibers of the pudendal nerve to the external (voluntary) sphincter, the tone of which initially increases, and is inhibited as the strength of stimulation increases. At the same time, the diaphragm and abdominal muscles contract, which leads to a decrease in the volume of the abdominal cavity and an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, which promotes the act of defecation.

The duration of evacuation, i.e. the time during which the intestines are released from the contents, in a healthy person reaches 24 - 36 hours. Parasympathetic nerve fibers running as part of the pelvic nerves inhibit the tone of the sphincters, enhance rectal motility and stimulate the act of defecation. Sympathetic nerves increase sphincter tone and inhibit rectal motility.

Methods for studying the functions of the digestive tract

The secretory and motor activity of the gastrointestinal tract is studied both in humans and in animal experiments. A special role is played by chronic studies, when the animal first undergoes a corresponding operation and after a recovery period the functions of the gastrointestinal tract are studied. These operations are based on the principle of maximum preservation of nerve and vascular connections that ensure the performance of the functions of a particular organ.

To study secretory activity, the excretory ducts of the glands are exposed to the skin, or the fistula method. A fistula is an artificially created connection between the organ cavity and the external environment. Fistula research methods make it possible to obtain pure digestive juices with subsequent study of their composition and digestive properties on an empty stomach, after feeding or other stimulation of secretion; study the motor, secretory and absorption functions of the digestive organs; study the mechanisms of regulation of the activity of the digestive glands. V. A. Basov (1842) was the first to perform gastric fistula surgery. However, using this method it was impossible to obtain pure gastric juice.

Positive effect of hydrogen water on intestinal motility

You will be surprised to know what is produced in our intestines. This is hydrogen.

Intestinal bacteria constantly synthesize or consume macro- and microelements. The produced substances travel further throughout the body. In this case, some bacteria consume molecular hydrogen, while others produce it. This process does not stop and occurs in every living organism.

In case of any human illness, the intestines release even more hydrogen to start all processes in the body.

Positive effect of hydrogen water on intestinal motility

But there is so little of it that it practically does not reach other organs and tissues.

Studies have shown that thanks to hydrogen, oxidation processes in the body are reduced, that is, it is hydrogen that has a positive effect on the intestines.

Nowadays, there is not a person left who has not heard about how important it is to maintain a drinking regime, but not everyone suspects how destructive the lack of sufficient water is for the entire digestive system and intestines in particular.

A process occurs in which enzymatic activity decreases, which causes a slowdown in the movement of stool, leading to constipation (hardening of the stool).

Impaired intestinal motility is a consequence of almost any disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Let us divide all disorders of intestinal motility into three groups:

- Changes in sphincter tone.

- Changes in pulsatile activity, that is, the process of contraction of smooth muscle cells in the intestinal walls.

- Reverse move.

This is interesting!

“The benefits of simple foods for your body” Read more

Diarrhea or constipation, already mentioned above, are obvious signs of violations.

Hydrogen is transferred into the body from the intestines by water, that is, it does not cause difficulties for it to overcome biological membranes and neutralize cytotoxic radicals that provoke oxidative stress. Precisely because hydrogen water is similar to the internal environment of our body, the intestines easily absorb it, the work of the smooth muscles of the intestinal walls is stimulated, which ultimately leads to the normalization of bowel movements, as well as to improved functioning of the intestinal microbiota.

So, we know that hydrogen is produced by our body, namely by the intestinal microflora. For example, lactobacilli, together with molecular hydrogen, have antioxidant properties, which reduce the activity of an enzyme such as peroxidase.

The cells of the large intestine are always in a state of “permanent inflammation”, since the entire mucous membrane of the human intestine, especially the large intestine, is infiltrated with cells that provide immunity (macrophages, lymphocytes), therefore, in order for the fight against pathogenic microflora to occur and the motility of the large intestine to function normally, hydrogen is needed.

The pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis proves to us: in order for sulfates to be reduced into sulfites, and for methane to be formed from carbon dioxide and hydrogen, hydrogen is needed in sufficient quantities.

In addition, we studied how microorganisms influence the motility of the large intestine: short-chain fatty acids synthesized by microflora stimulate increased motility, as well as easier bowel movements.

But intestinal motility depends not only on microorganisms; hydrogen itself affects the smooth muscles of the intestinal walls.

Positive effect of hydrogen water on intestinal motility

To prove this statement, it was necessary to conduct a scientific experiment on rats. The rats studied suffered from ischemic intestinal disease, which was a consequence of compression of the artery feeding it (the mesenteric artery). However, after systematic treatment of the intestine, the severity of the disease was reduced by inducing apoptosis (programmed cell death).

This confirms that hydrogen has a positive effect on contractile intestinal function, normalization of intestinal motility occurs, which leads to easier defecation and renewal of enterocytes, as well as the fight against oxidative stress, which provoke acute and chronic inflammatory processes.

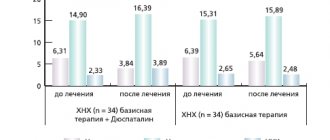

Restoration of motor skills in functional gastrointestinal disorders in adult patients

Lecture transcript

XXV All-Russian Educational Internet Session for doctors

Total duration: 15:00

00:00

Oksana Mikhailovna Drapkina, Secretary of the Interdepartmental Scientific Council on Therapy of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor:

— We move on to Elena Aleksandrovna Poluektova’s message. Restoration of motor skills in functional gastrointestinal disorders in adults.

Elena Aleksandrovna Poluektova, Candidate of Medical Sciences:

- Dear Colleagues! Marina Fedorovna comprehensively presented information about the mechanisms of formation of motor dysfunction, about the mechanisms of action of the main groups of drugs that can be used to restore motor skills.

My report will mostly focus on the results of clinical studies of the use of certain drugs for functional disorders.

Let's start with functional dyspepsia syndrome. This disease is known to be quite common in the population. According to various authors, it occurs from 7% to 41%.

This slide lists medications that can be used to treat functional dyspepsia syndrome. But since we are talking about restoring motor skills, let’s focus on prokinetics.

This slide presents the results of 14 studies (this is a meta-analysis). In total, more than a thousand patients took part in these studies. It turned out that the effectiveness of prokinetics in functional dyspepsia syndrome is 61%. The placebo effect is 41%. It is necessary to treat four patients with functional dyspepsia syndrome with prokinetics in order to achieve an effect in one patient. In principle, these values are quite good.

What medications can be used to restore motor skills in patients with SFD? These are cholinergic receptor agonists, dopamine receptor agonists, type IV serotonin receptor agonists, motilin receptor agonists, combination drugs, and peripheral opioid receptor agonists.

Groups of drugs that are actually used in practical medicine to restore motor skills in patients suffering from functional dyspepsia syndrome are highlighted in darker font.

02:28

So, the first group of drugs. Dopamine receptor antagonists (metoclopramide and domperidone). These drugs increase the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter. They enhance the contractility of the stomach and prevent its relaxation. Accelerate gastric emptying. Improves antroduodenal coordination. They have an antiemetic effect.

However, it should be remembered that drugs in this group (mainly, of course, metoclopramide) have a fairly large number of side effects. Muscle hypertonicity, hyperkinesis, drowsiness, anxiety, depression, as well as endocrine disorders. The incidence of side effects reaches 30%.

The next group of drugs. Combined-action drugs that are both dopamine receptor antagonists and acetylcholinesterase blockers. This group of drugs includes itopride hydrochloride. The drug enhances the propulsive motility of the stomach and accelerates its emptying. Also causes an antiemetic effect.