- Magazine archive /

- 2010 /

Chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs: diagnostic algorithm and treatment

Zvenigorodskaya L.A., Samsonova N.G., Toporkov A.S.

The problem of diagnosis and treatment of chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs (CHD) is discussed. Difficulties in diagnosing damage to the visceral arteries are due to the fact that the clinical manifestations of CIBOP are characteristic of various diseases of the gastroduodenal zone, gallbladder, pancreas and intestines. Along with the assessment of clinical data, laboratory and instrumental research methods, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy; colonoscopy with biopsy of the mucous membrane of the stomach, duodenum and colon, sonographic examination; the main role in verifying the diagnosis of CIBOP belongs to methods that directly reveal occlusive-stenotic changes in the visceral arteries - Doppler ultrasound and angiography. In the treatment of CIBOP, both conservative and surgical treatment methods are used. The tactics of conservative therapy depend on the severity of the clinical manifestations of CIBOP, i.e., the functional class of the disease.

Key words: dystrophic changes in the digestive organs, weight loss, abdominal pain, visceral arteries, chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs, dyspeptic disorders

Chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs (CHD) is a disease that occurs when blood circulation is impaired in the unpaired visceral branches of the abdominal aorta: the celiac trunk (CT), superior (SMA) and inferior (IBA) mesenteric arteries. Clinically, CIBOP is manifested by abdominal pain, usually occurring after eating, disturbances in the motor-secretory and absorption functions of the intestine, and in some patients, progressive weight loss [1].

The terminology of chronic abdominal ischemia is varied. There are more than 20 terms that define this symptom complex; the most famous of them are: “angina abdominalis”, “mesenteric arterial insufficiency”, “chronic intestinal ischemia”, “abdominal ischemic syndrome”.

Many doctors know about this disease, but not everyone understands its etiology and clinical manifestations; do not fully understand the correct diagnostic and clinical algorithms for the management of chronic bronchitis. This may be due to the fact that CIBOP is usually considered a rare and difficult to diagnose disease [1–3]. However, research by Pokrovsky A.V. (1988) showed that damage to the unpaired visceral branches of the abdominal aorta occurs in 73.5% of cases in individuals with atherosclerosis of the coronary arteries of the heart, arteries of the brain, as well as arterial hypertension - hypertension [4]. Valentine RJ et al. (1991) found atherosclerotic lesions of the SN and SMA in 30% of examined patients with hypertension and coronary heart disease (CHD) during aortography [5].

Difficulties in diagnosing damage to the visceral arteries are due to the fact that the clinical manifestations of CIBOP are characteristic of various diseases of the gastroduodenal zone, gallbladder, pancreas and intestines. These patients are more often hospitalized in gastroenterological hospitals, where the identified functional and morphological changes in the digestive organs are regarded as “banal” chronic inflammation, and therapy corresponding to this diagnosis turns out to be ineffective.

Etiology of CIBOP

The reasons leading to CIBOP are quite clearly and definitely divided into two groups. The first consists of arterial diseases (atherosclerosis, nonspecific aortoarteritis, abnormalities of vascular development, angiopathy, etc.). The second group includes extravascular compression of the SN and mesenteric arteries by the medial leg and falciform ligament of the diaphragm, nerve ganglia of the solar plexus, periarterial fibrous tissues, and tumors. Intravasal lesions are more common (62–90%) than extravasal lesions (10–38%) [6, 7]. Among the intravasal causes of damage to the visceral arteries, the leading place belongs to atherosclerosis (52.2–88.3%) and nonspecific aortoarteritis (22–31%). The most common cause of extravasal compression is the arcuate ligament of the diaphragm or its medial crura (40.8–72.5%). Thus, various etiological factors can cause damage to the visceral arteries and lead to circulatory disorders in the digestive organs [1, 2, 8, 9, 10, 11].

Clinical picture of mesenteric circulation disorder

Mesenteric circulation disorders can be acute or chronic. The first form, leading to the development of intestinal infarction, has more or less distinct symptoms and is correctly diagnosed in a significant number of cases [8]. As for the clinical picture of chronic disorders of the blood supply to the digestive organs, it is less defined, since it is similar to the clinical picture of a number of diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. The clinical manifestations of chronic ischemia of the digestive organs (CIOD) are extremely diverse; the disease has a lot of clinical “masks”.

In 94–96% of patients, the main symptom is pain that occurs after eating. This fact is explained by insufficient blood flow to the digestive organs during the period of their maximum activity, as well as the sensitivity of the digestive organs to ischemia. The nature of the pain is different: in the initial stage of the disease, the pain is equivalent to a feeling of heaviness in the epigastric region, then with the worsening of circulatory disorders, aching pain appears, the intensity of which gradually increases [8, 12]. The second common sign of chronic ischemia of the digestive organs is intestinal dysfunction, manifested in the form of a violation of the secretory and absorption functions of the small intestine (flatulence, unstable frequent loose stools) and the evacuation function of the large intestine with persistent constipation. Progressive weight loss is considered the third most common symptom of CIOP and is associated both with the refusal of patients to eat due to pain, and with a violation of the secretory and absorption functions of the small intestine, which is especially pronounced in the late stage of the disease [8, 13, 14].

A pathognomonic sign during an objective examination is a systolic murmur 2–4 cm below the xiphoid process in the midline, determined when the abdominal aorta and/or SN are predominantly affected. With severe stenosis or occlusion of the visceral arteries, systolic murmur may be absent, which is not a reason to exclude their damage [8, 13].

The localization of ischemic damage to the digestive organs depends on the visceral artery feeding them. Thus, when an emergency occurs, the organs of the upper floor of the abdominal cavity are predominantly affected: the liver, pancreas, stomach, duodenum (duodenum) and spleen. Stenosis or occlusion of the SMA is manifested by various dysfunctions of the small intestine, and damage to the IMA often causes ischemia of the large intestine [3, 14]. At the same time, the developed collateral network between the visceral arteries contributes to long-term functional compensation in conditions of impaired main blood flow, therefore, occlusive or stenotic lesions of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta do not always lead to the appearance of CIOP symptoms. The most striking clinical picture of CIOP is described when two or all three visceral arteries are affected [3, 8, 12, 14].

The frequency of ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum when the patency of unpaired visceral arteries is impaired is noteworthy. Thus, Olbert F. et al. found them in 18% of patients with SN stenosis and in 50% of patients with SMA lesions [15]. Other authors found ulcerative lesions of the stomach and duodenum in more than 30% of cases of CIBOP of atherosclerotic origin, and suggested that peptic ulcer disease in elderly and senile patients is the most common manifestation of CIBOP [3, 9, 16].

According to a survey conducted at the Central Research Institute of Gastrointestinal Diseases, ischemic gastroduodenopathy was detected in 46.2% of cases and ranks first among the clinical forms of CIBOP [14]. With chronic disruption of the blood supply to the stomach and duodenum, progressive atrophy of the mucous membrane of these organs is observed, while the mucous membrane of the antrum of the stomach is affected more often than the body and fundus, which is associated with the characteristics of vascularization and sensitivity to hypoxia. Impaired blood supply to the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum leads to a decrease in the production of protective mucosubstances by epithelial cells, which contributes to ulcer formation [17]. Characteristic clinical features of erosive and ulcerative lesions of the gastroduodenal zone in chronic abdominal ischemia are manifestation of the disease in the form of bleeding, lack of seasonality of exacerbations, atypical clinical picture, high frequency of concomitant cardiovascular diseases, relapses, large size of the ulcer defect, low effectiveness of antiulcer therapy.

The incidence of ischemic pancreatopathy in CIBOP is 33.9% [17]. The main feature of the blood supply to the pancreas is the absence of its own large arteries. The pancreas is supplied with blood from the branches of the common hepatic, superior mesenteric and splenic arteries. It is these features that determine the incidence of pancreatic necrosis, as well as the frequency of ischemic pancreatopathies during abdominal ischemia. There are certain difficulties in the differential diagnosis of ischemic pancreatopathy with banal chronic pancreatitis, since the clinical manifestations of chronic ischemic pancreatitis are nonspecific. Both conditions are characterized by: intense pain after eating in the epigastric region, left hypochondrium, intractable (or poorly controlled) with antispasmodics, as well as sitophobia, pancreatic insufficiency, weight loss [17]. Ischemic pancreatopathy can occur as acute ischemic pancreatitis, including fatal, chronic ischemic pancreatitis. It should be noted that chronic pancreatitis itself can be the cause of abdominal ischemia. Pancreatic cysts, exerting compression on nearby vessels, can eventually cause abdominal ischemia.

Ischemic damage to the large intestine (ICH), which, according to our data, ranks third among other forms of CIBOP deserves special attention [17]. Thus, when examining individuals with clinical symptoms of ischemic lesions of the colon (IPTC) in the mucous membrane of the sigmoid colon (the most vulnerable to disruption of the blood supply to the colon, since it is located in the area of underdeveloped anastomoses), signs of impaired microcirculation and inflammation characteristic of ischemic lesions were almost always revealed . Microscopic signs of ischemia occurred even before the development of macroscopic changes.

Histological examination of the mucous membrane in these cases revealed superficial necrosis of the epithelium, a decrease in the number of goblet cells, focal lymphoid cell infiltrates, paresis and plethora. These changes were accompanied by emptying of blood vessels, the development of stasis, thrombosis of the microvasculature and plasmorrhagia. We considered the described morphological changes in the mucous membrane of the sigmoid colon, identified by biopsy, to be the earliest reliable signs of IPTC.

Based on the data obtained, we identified another form of IPTC - microscopic. By analogy with the known microscopic (lymphocytic and collagenous) colitis, we called this form “microscopic ischemic colitis” (MIC). This form of IPTC develops in elderly and senile patients suffering from diseases of the cardiovascular system. Characteristic symptoms of microscopic ischemic colitis are: abdominal pain with predominant localization in the left iliac region, appearing after eating; constipation; abdominal discomfort and flatulence. On examination, the sigmoid colon is painful, spasmodic, and the cecum is often dilated; A positive Obraztsov symptom is characteristic [18].

Depending on the severity of clinical manifestations and the degree of disturbance of visceral blood flow, the following functional classes of CIBOP are distinguished [13, 14]: • First functional class (I FC) – absence of signs of disturbance of blood flow at rest and the appearance of abdominal pain only after a stress test. Clinical symptoms are not expressed. • Second functional class (II FC) – the presence of signs of circulatory disorders at rest and their intensification after functional load. Severe clinical symptoms: pain and dyspeptic syndromes, weight loss, impaired pancreatic function, impaired secretory absorption function of the intestine. • Third functional class (III FC) – the presence of severe circulatory disorders, detected at rest and combined with constant pain, severe weight loss and dystrophic changes in the digestive organs.

Advantages of treatment in our clinic

- Availability of the latest modern diagnostic equipment (high-resolution MSCT, high-density MRI, endoscopy, colonoscopy), necessary to make a diagnosis and exclude other diseases with similar symptoms (Crohn's disease, diverticulitis, malignant tumors of the colon, intestinal infections).

- Extensive experience in performing colonoscopy – the “gold” standard for diagnosing ulcerative colitis. Allows you to carefully examine the wall of the large (and even the final section of the small) intestine from the inside, as well as take a piece of its tissue for histological examination (carry out a biopsy).

- Extensive experience in the treatment of nonspecific ulcerative colitis, including cases with complications.

- Continuous interaction between the surgeon and the gastroenterologist makes it possible to timely identify indications for surgical treatment and perform the operation at the most appropriate period.

- Preference is given to minimally invasive (laparoscopic) interventions.

Diagnostic methods

Diagnosis of CIBOP is based on the same principles as ischemic heart disease, i.e., detailing the patient’s complaints, careful collection of anamnesis, identifying risk groups for the possible development of atherosclerotic lesions of the abdominal aorta and its unpaired visceral branches (sensitivity - 78%), objective examination of the abdominal aorta (palpation, auscultation). Analysis of characteristic anamnestic data, complaints, signs of circulatory disorders in other arterial basins, as well as systolic murmur heard in the projection of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta, suggests a diagnosis of CIBOP.

Due to the fact that objective data in the diagnosis of CIBOP are scarce, the following additional studies are needed: blood lipid spectrum, indicators of the blood coagulation system (fibrinogen, activated partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio), aimed at identifying atherogenic dyslipidemia, disorders of the rheological properties of blood.

Additional research methods that reveal pathological changes in the organs of the gastrointestinal tract provide some assistance in the diagnosis of CIBOP. Along with laboratory research methods, instrumental ones are used, including esophagogastroduodenoscopy; colonoscopy with biopsy of the gastric mucosa, duodenum, and colon; sonographic examination of the abdominal aorta and pancreas, in which the shape, contour dimensions, echostructure and echodensity of the organ are studied. As a rule, an ultrasound examination of the abdominal aorta in transverse and longitudinal scanning visualizes its uneven, jagged intima, as well as echo-positive inclusions in its lumen, which indicates an atherosclerotic lesion.

However, the main role in verifying the diagnosis of CIBOP belongs to methods that directly detect occlusive-stenotic changes in the visceral arteries - Doppler ultrasound and angiography. Doppler ultrasound opens up great opportunities in the diagnosis of CIBOP, and the results obtained have a high correlation with angiography data [19]. Thus, to confirm the diagnosis of CIBOP, all patients undergo a Doppler examination of the main arteries of the abdominal cavity (CH, SMA, BA, splenic artery) both on an empty stomach and after a standard food load (500 ml of milk 3.5% fat and 300 g of unsweetened wheat bakery products). When these indicators change compared to the norm, the degree of ischemia of the digestive organs is diagnosed. Nutritional load is a functional test for assessing mesenteric blood flow and allows you to assess the functional reserves of the digestive organs. In this case, the following parameters are determined that reflect the hemodynamics of the arterial bed: maximum linear blood flow velocity (Vmax), minimum linear blood flow velocity (Vmin), average blood flow velocity (TAMX), pulsatility index (PI), resistance index (RI), systolic-diastolic ratio (S /D), and also conduct a qualitative assessment of Doppler curves. As a rule, when visceral blood flow is disrupted, an increase in all hemodynamic parameters is observed.

When organic damage to the visceral arteries is detected, according to Doppler studies, in order to determine treatment tactics, radiopaque aortoarteriography is performed in direct and lateral projections according to the well-known Seldinger technique, and recently, in connection with the development of radiation diagnostic methods, computed tomographic angiography (CTangiography) is used. This method combines traditional computed tomography with angiography, which allows you to obtain detailed images of blood vessels. Because this test injects contrast into a vein rather than an artery, it is considered less invasive than simple angiography.

HIBOP treatment

In the treatment of CIBOP, both conservative and surgical treatment methods are used. The tactics of conservative therapy depend on the severity of the clinical manifestations of CIOP, i.e. the FC of the disease. Thus, patients with CIBOP I FC are prescribed conservative treatment, which includes, first of all, a strict lipid-lowering diet: 10–15% proteins, 25–30% fats, 55–60% polysaccharide carbohydrates, vegetable fats, and foods containing fiber. Meals should be fractional, in small portions. Diet recommendations take into account the individual characteristics of the patient’s body and concomitant diseases.

The second important component of normalizing lipid levels is the use of lipid-lowering agents. This type of therapy is used taking into account individual tolerance and medications. It is possible to prescribe drugs from the statin group: simvastatin (Simgala) at a dose of 20–40 mg/day, fluvastatin (Leskol) at a dose of 40 mg/day, atorvastatin (Liprimar) at a dose of 10–40 mg/day. The maximum lipid-lowering effect occurs 2–3 weeks from the start of treatment, however, the results of therapy to reduce cardiovascular complications begin to appear no earlier than 6–9 months from the start of taking statins. Due to the need for long-term therapy, careful monitoring of the level of liver enzyme activity is required. To prevent the manifestation of the hepatotoxic effect of statins, it is advisable to conduct courses of hepatotropic therapy with essential phospholipids (Essliver forte, Essentiale, Phosphogliv) in courses of 2 months, 2-3 times a year. The use of essential phospholipids helps to normalize the blood lipid spectrum, lipid peroxidation indicators and the antioxidant defense system. To correct the lipid spectrum of the blood, patients with concomitant liver pathology (steatosis, steatohepatitis, fibrosis), as an alternative, can be prescribed ursodeoxycholic acid drugs in a standard dosage of 15 mg/kg.

In patients with a high risk of developing atherosclerosis, in order to achieve target levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) and reduce side effects, the most promising and highly effective is the use of a combination of a statin (simvastatin - Simgala 10 mg) with a cholesterol absorption inhibitor (ezetimibe - Ezetrol 10 mg). Modern provisions are based on double inhibition of cholesterol synthesis and its absorption, the use of a selective inhibitor of intestinal absorption of cholesterol - ezetimibe. The use of a combination of ezetimibe + statin increases the reduction in LDL cholesterol levels by 40% without causing an increase in transaminase levels. When conducting dual therapy, it is possible to achieve target LDL cholesterol levels within 2 weeks.

To improve the rheological properties of blood, drugs from the group of low molecular weight heparins are used, in particular calcium nadroparin (Fraxiparin) in a dose of 0.3 ml once a day for 2 weeks. For the purpose of antioxidant protection, use the drug trimetazidine (Preductal) 20 mg 3 times a day with meals for 3 months, twice a year. To ensure an angioprotective effect and improve microcirculation, pentoxifylline (Trental) is prescribed 5 ml intravenously for 10 days, as well as ethylmethylhydroxypyridine succinate (Mexidol) 100 mg intravenously once a day for 2 weeks.

In order to normalize blood pressure and dilatation of coronary vessels, as well as improve the perfusion of internal organs, patients with chronic chronic hypertension with concomitant hypertension and coronary artery disease are prescribed: • nitrates - isosorbide dinitrate 10 mg 3 times a day (maximum - 20 mg 4 times a day); • β-blockers – atenolol 50–100 mg/day, metoprolol 100 mg/day; • angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors – monopril 10 mg 2 times/day (maximum – 20 mg 2 times/day) for a long time; • calcium channel blockers – verapamil 40 mg 3 times/day (maximum 80 mg 3 times/day), amlodipine 10 mg/day.

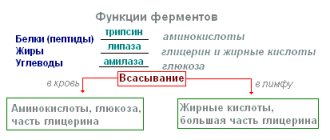

To relieve dyspepsia, it is necessary to prescribe enzyme preparations - pancreatin (Creon) at a dose of 10,000 units 3 times a day (if necessary, a higher dose can be taken) for 2-3 weeks.

In order to relieve pain and plan the treatment of bowel disorders, it is advisable to use antispasmodics - mebeverine (Duspatalin) 1 capsule 2 times a day (course of treatment - 2-3 weeks). Duspatalin has a positive property: eliminating spasm of intestinal smooth muscles, it does not cause hypotension, which is very important in the treatment of elderly patients in whom hypotension of the bowel is more likely to occur.

To reduce the severity of flatulence, using Meteospasmil 1 capsule 2-3 times a day is effective. The drug of choice for the treatment of constipation in elderly patients is lactulose (Duphalac) 30–100 ml/day. The advantage of this drug is that it does not require additional fluid intake, is not addictive, is not absorbed (therefore it can be prescribed for diabetes), does not cause electrolyte disturbances, and is effective for liver diseases. For constipation combined with pathology of bile secretion, a combination of prokinetics - metoclopramide (10 mg 3 times a day 15 minutes before meals) or domperidone (10 mg 3 times a day before meals) with choleretic agents (Allochol, Cholenzyme, Chophytol) for up to two to three weeks.

In order to correct the intestinal microflora, it is necessary to sanitize the colon with metronidazole (250 mg 4 times a day), Alpha Normix (2 tablets 2 times a day) for 7–10 days, followed by the administration of probiotics - Bifiform (2 capsules in the morning) , Probifor (25–30 doses 3 times/day), Linex (2 capsules 3 times/day); Duration of administration - 3-4 weeks, and prebiotics - Duphalac (at a dose of 5-10 ml/day), Hilaka forte (40-60 drops three times a day), Sporobacterin (2-4 ml) for 4 weeks.

The positive effect of conservative therapy is the disappearance or reduction of pain, dyspeptic symptoms, a decrease in plasma lipid levels, and an improvement in hemodynamic parameters.

Treatment tactics for patients with FC II CIBOP are determined individually. The choice of treatment is based on the results of radiopaque aortoarteriography. If hemodynamically insignificant stenoses (less than 50%) of the visceral arteries are detected in these patients, conservative therapy is prescribed.

Patients with HIBOP III FC, as well as patients with HIBOP II FC with hemodynamically significant stenoses, are sent to the departments of vascular surgery, where they undergo reconstructive surgical interventions: endarterectomy, various types of bypass operations, as well as X-ray endovascular treatment methods (angioplasty and stenting of narrowed areas of the affected areas). arteries).

Literature

1. Kolomoiskaya M.B., Dikshtein E.A., Mikhailichenko V.A. and others. Ischemic bowel disease. Kyiv, 1986. 2. Petukhov V.A. Dyslipoproteinemia and its correction in obliterating atherosclerosis. Diss. doc. honey. Sci. M. 1995. 3. Potashov L.V., Knyazev M.D., Ignashov A.M. Ischemic disease of the digestive system. 1985. 4. Pokrovsky A.V., Kazanchyan P.O., Dyuzhikov A.A. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic ischemia of the digestive organs. Rostov, 1982. 5. Valentine RJ, Martin JD, Myers SI, et al. Asymptomatic celiac and superior mesenteric artery stenosis are more prevalent among patients with unsuspected renal artery stenosis. J Vase Surg 1991;14(2):195–99. 6. Plonka AJ, Tolloczko T, Lipski M, et al. Atherosclerotic narrowings of the mesenteric circulation. Vac Surg 1989;92:202–05. 7. Quandalle P, Chambon JP, Wolffle D, et al. Diagnostic et traitement chirurgical de l'angor abdominal par stenose atheromateuse des arteres digestives. J Chir 1989;126(12):643–49.. 8. Abulov M.Kh., Murashko V.V. Clinical variants of chronic abdominal ischemia in mesenteric atherosclerosis // Therapeutic archive 1986. 11. pp. 119–22. 9. Croft RJ, Menon GP, Marston A. Does intestinal angina exist? A critical study of obstructed visceral arteries. Br J Surg 1981;68:316–18. 10. Mikkelsen WP, Berce CJ. Intestinal angina. Surg Clin North Amer 1965;2:1321–28. 11. Plonka AJ, Tolloczko T, Lipski M, et al. Atherosclerotic narrowings of the mesenteric circulation. Vac Surg 1989;92:202–05. 12. Kazanchan P.O. Clinic, diagnosis and surgical treatment of chronic occlusive lesions of the visceral branches of the abdominal aorta. Diss. doc. honey. Sci. M., 1978. 13. Kuznetsov M.R., Zvenigorodskaya L.A., Samsonova N.G. and others. Chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs: clinical options and treatment tactics // Thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1999. 4. pp. 35–9. 14. Samsonova N.G. Chronic ischemic disease of the digestive organs: clinical course options, diagnosis, treatment. Diss. Ph.D. honey. Sci. M., 2000. 15. Olbert F, Dittel E, Hagmuller G. Clinico-radiological findings in stenosis or occlusion of the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries. Angiology 1973;24:338–44. 16. Pokrovsky A.V., Kazanchyan P.O., Grinberg A.A. and others. Functional and morphological state of the gastrointestinal tract in conditions of chronic circulatory disorders // Therapeutic archive. 1983. 2. P.93–96. 17. Lazebnik L.B., Zvenigorodskaya L.A. Chronic ischemic disease of the digestive system. M., 2003. 136 p. 18. Zvenigorodskaya L.A., Samsonova N.G., Parfenov A.I., Khomeriki S.G. Clinical, functional and morphological changes in the colon in patients with chronic abdominal ischemia // Difficult patient. 2007. 15(16). pp. 32–5. 19. Moneta GL, Yeager RA, Dalman R. et al. Duplex ultrasound criteria for diagnosis of splanchnic artery stenosis or occlusion. J Vasc Surg 1991;14:511–20.

Postoperative period

In the normal course of the postoperative period, discharge is made 5-7 days after surgery.

In the postoperative period, a gradual reduction in the intake of hormonal drugs is required, up to their discontinuation.

Regular examination and observation by an endocrinologist, gastroenterologist and proctologist is required.

Cost of treatment

Free treatment under compulsory medical insurance policy

A type of social insurance for citizens of the Russian Federation, which provides guarantees of free medical care in the detection of surgical diseases.

Quota treatment (VMP)

Providing medical care for the most severe diseases of the gastrointestinal tract, requiring the mandatory use of expensive instruments and/or the use of complex surgical techniques.