Chronic pancreatitis: exocrine insufficiency and its correction

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is an inflammatory disorder that causes irreversible anatomical changes and damage, including inflammatory cell infiltration, fibrosis, and calcification of pancreatic tissue with destruction of glandular structure, thereby affecting normal digestion and nutrient absorption in the digestive tract. .

According to modern concepts, CP is a non-infectious inflammatory disease of the pancreas, often associated with a pain syndrome, characterized by the development of irreversible morphological changes in the parenchyma and ductal system of the pancreas with the progressive replacement of the functioning structures of the organ with connective tissue, leading to disruption of exocrine and endocrine functions [1].

HP is accompanied by:

- disruption of the processes of digestion and absorption;

- development of bacterial overgrowth in the small intestine;

- impaired motor function of the gastrointestinal tract.

Anatomy

In Fig. Figure 1 shows the anatomical structure of the pancreas.

The pancreas is an elongated, conical organ located in the back of the abdominal cavity, behind the stomach.

The pancreas consists of two types of glands: exocrine and endocrine.

The exocrine gland produces digestive enzymes (trypsin, chymotrypsin, lipase and alpha-amylase). These enzymes enter the duodenum through a network of pancreatic ducts.

The endocrine gland consists of the islets of Langerhans and secretes polypeptide hormones (glucagon and insulin) into the bloodstream.

Exocrine tissues make up about 99% of the pancreas, and endocrine tissues make up about 1%. Exocrine tissues are made up of exocrine cells that produce digestive enzymes. The endocrine tissue of the pancreas consists of small bundles of cells called islets of Langerhans. There are two main types of endocrine cells: alpha and beta cells. Alpha cells produce the hormone glucagon, which increases blood glucose levels. Beta cells produce the hormone insulin, which lowers blood glucose levels.

Epidemiology

Over the past 30 years, there has been a worldwide trend towards an increase in the incidence of acute and chronic pancreatitis by more than 2 times. In developed countries, the incidence of CP ranges from 5–10 cases per 100 thousand population; in the world as a whole - 1.6–23 cases per 100 thousand population per year. The prevalence of CP in Europe is 25.0–26.4 cases per 100 thousand population, and in Russia - 27.4–50 cases per 100 thousand population. In most cases, CP develops on average at the age of 35–50 years [2].

Classification

Currently, many different classifications of CP have been proposed, which are based on the principles of structuring the variants of this nosology according to etiology, clinical course, morphological characteristics and the presence of complications.

Among the new modern classifications that most fully take into account the causes of pancreatitis, it is necessary to highlight the etiological classification TIGAR-O (Fig. 2): Toxic-metabolic (toxic-metabolic), Idiopathic (idiopathic), Genetic (hereditary), Autoimmune (autoimmune), Recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis (recurrent and severe acute pancreatitis) or Obstructive (obstructive) [3].

The TIGAR-O classification is focused on understanding the causes of CP and choosing the appropriate diagnostic and treatment tactics. This is its main advantage and convenience for practitioners.

Clinical manifestations

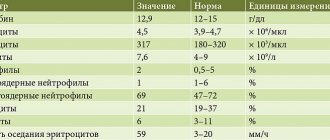

Clinical manifestations of CP depend on the period and severity of the disease. They can be divided into several syndromes (Table 1).

Diagnostics

Differential diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis should be carried out taking into account the causes of acute or chronic abdominal pain of unknown etiology. Increases in serum amylase and lipase levels are nonspecific and can occur with superior mesenteric ischemia, diseases of the biliary system, complicated peptic ulcer disease, and renal failure. The main diseases with which it is recommended to differentiate CP are presented in Table. 2 [5].

There is no generally accepted gold standard for diagnosing CP. No known clinical, endoscopic or radiological method can definitively diagnose CP. However, there are many diagnostic methods that can be divided into five categories.

1. Pancreatic function tests

Functional pancreatic tests are divided into direct and indirect.

Direct tests include stimulation of the pancreas using secretory agents (secretin or cholecystokinin). These tests are invasive (requiring endoscopic procedures), expensive, and generally not performed outside of specialized centers. The sensitivity of direct tests for diagnosing late chronic pancreatitis is high, and for diagnosing early chronic pancreatitis it is about 70–75%.

Direct tests include:

• secretin test:

- classic tube (after administration of secretin, duodenal contents are sucked out through a nasogastric tube and the activity of bicarbonates and pancreatic enzymes is determined);

- endoscopic (duodenal contents are collected during esogastroduodenoscopy);

- magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) with secretin - after stimulation with secretin, the volume of pancreatic juice secreted in the duodenum is determined after 15, 30, 45, 60 minutes.

Indirect tests of pancreatic function include fecal elastase, fecal fat measurements, and serum trypsinogen.

Indirect methods:

- calculation of the fat absorption coefficient (based on 3-day stool collection);

- serum trypsin;

- fecal elastase-1 or pancreatic elastase-1 (PE-1);

- fecal chymotrypsin;

- 13C-triglyceride breath test.

The 3 g fat collection test requires collection of stool within 72 hours of ingestion of a known amount of fat (100 g per day). Excretion of more than 7 g of fat in stool per day is indicative of fat malabsorption, whereas excretion of more than 15 g per day is considered severe fat malabsorption. However, assessing fecal content over 3 days is a cumbersome test for both patients and laboratory personnel and is very rarely done in routine practice. In general, indirect tests are moderately sensitive and specific for diagnosing CP.

Over the past decade, the enzyme immunoassay method for determining PE-1 in the stool of patients with CP has become widespread. PE-1 is a human-specific enzyme that is not degraded during intestinal transit, is enriched 5-6 times in feces and, therefore, is a marker of exocrine pancreatic function.

In table Table 3 presents criteria for assessing the degree of exocrine pancreatic insufficiency.

The sensitivity of the elastase test in patients with severe and moderate exocrine pancreatic insufficiency is close to that of the secretin-pancreozymin test and, according to most foreign researchers, is 90-100% (for mild degrees - 63%), specificity - 96%. This method is simple, fast and inexpensive, has no restrictions in application, and allows us to determine the state of the exocrine function of the pancreas at earlier stages than before [1]. It is also important that patients should not consume the specific substrate (fat) before testing and should not stop pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy.

Chymotrypsin remains relatively stable when passing through the gastrointestinal tract. Its determination is easy to perform and relatively inexpensive, but this test is characterized by low sensitivity for mild to moderate pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and low specificity for certain pathologies of the gastrointestinal tract not associated with the pancreas.

Breath tests consist of oral ingestion of various substrates, primarily 13C-labeled triglycerides, which are hydrolyzed in the small intestinal lumen to a degree proportional to pancreatic lipase activity. Exhaled 13CO2 is determined by mass spectrometry or infrared spectroscopy, but, like other indirect tests, this test has low sensitivity and specificity.

2. Histological studies

Histological features of CP include parenchymal fibrosis, acinar tissue atrophy, ductal distortion, and pancreatic calcification [6]. Histological methods are the most specific for diagnosing CP, but they are rarely available in clinical practice, and therefore additional studies are required to make a definitive diagnosis of CP.

3. Radiological studies

CT scan

Computed tomography (CT) is a widely used imaging modality and is an objective and reliable method for measuring pancreatic morphology. “Classical” diagnostic signs of CP on CT include atrophy, dilated pancreatic duct and pancreatic calcification [6].

Although the diagnosis of early CP using CT is not always reliable, CT should nevertheless be performed in all patients to exclude gastrointestinal malignancies [6]. In addition, CT can be used in the evaluation of complications associated with CP, such as pseudocysts, pseudoaneurysms, duodenal stenosis, and malignancies. Overall, CT remains the best screening tool for identifying CP and excluding other intra-abdominal pathology that may be indistinguishable from CP based on clinical symptoms alone.

Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography with secretion stimulation

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is more sensitive than CT. It is used to diagnose CP as the initial radiological imaging modality with unambiguous CT scanning [6]. MRCP allows one to assess the condition of the main duct of the pancreas, while visualization of the lateral branches of the pancreas is not complete [6]. Stimulation of pancreatic secretion provides better visualization of abnormalities of the main pancreatic duct and its branches. Secretin stimulates secretion into the pancreatic ducts and increases the tone of the sphincter of Oddi during the first 5 minutes, preventing the release of fluid through the papilla of Vater [6]. Stimulation increases the absolute volume of pancreatic secretion, which fills all ducts and branches of the pancreas, thereby allowing the detection of moderate ductal changes in the initial stage of the disease, which are not detected using conventional MRCP. MRCP is used to diagnose complications of CP, such as biliary complications.

Morphological diagnostic criteria for CP [7] are presented in Fig. 3.

Negative factors associated with these methods include time and radiation exposure limitations coupled with the technical complexity of the test [6].

4. Endoscopic examinations

Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) provides visualization of the entire pancreas and nearby internal organs [6]. Although EUS is a more invasive test than CT and MRI/MRCP, it is the most sensitive for detecting minimal structural changes in the pancreas associated with CP, and therefore the most informative for minimal changes in the pancreas.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is considered a sensitive test for the diagnosis of CP. With the help of ERCP, it is possible to determine the dilation or stricture of the main pancreatic duct and its branches, as well as to identify early signs of CP [6]. When performing ERCP, it is possible to carry out therapeutic manipulations, such as dilatation of the main duct, removal of stones and stenting of the canal.

An additional advantage is the possibility of obtaining pancreatic secretions during ERCP [6].

Endosonographic criteria [7] are presented in Fig. 4.

Endoscopic elastography (EE) of the pancreas

Elastography of the pancreas is a new and promising method for diagnosing pancreatic diseases, based on determining the stiffness and rigidity of its tissue. Five types of elastographic patterns have been described, ranging from normal tissue to pancreatic fibrosis/calcification and pancreatic adenocarcinoma. EE results are shown on the monitor screen in real time in the form of color images [6]. Thus, EE makes it possible to quantify pancreatic fibrosis in CP. In one of the studies [8] on elastography in CP, a significant correspondence was found between endoscopic ultrasound criteria for CP and the deformation coefficient of pancreatic tissue in EE. A further study [9] showed the ability of EE to predict exocrine pancreatic failure in CP. Comparing EE with the C-mixed triglyceride breath test, the pancreatic gland strain ratio was higher in patients with exocrine insufficiency than in patients with normal exocrine insufficiency breath test scores. The probability of confirming exocrine insufficiency was 87% in patients with a pancreatic strain coefficient of more than 4.5. Therefore, EE results can be used to prescribe pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy even in the absence of other pancreatic function tests [6].

6. Genetic research

A genetic test that detects mutations in the cationic trypsinogen genes PRSS1, pancreatic secretory trypsin inhibitor SPINK-1 and mutations in the CFTR gene allows diagnosing hereditary pancreatitis. At the same time, the erroneous opinion is often expressed that the absence of genetic changes excludes a hereditary etiology of the disease.

Genetic screening is not recommended for every patient with CP, since alcohol abuse is the main cause of the disease in 60% of cases in adult patients. In patients with early onset CP, genetic screening may be offered after informed consent. At the same time, it is necessary to pay attention to the fact that the results of genetic tests will not change the proposed treatment of CP and the course of the disease. However, it may allow some patients to better understand their disease and also influence family planning. SPINK1 and CTRC variants and, to a lesser extent, common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the PRSS1 and CLDN2-MORC4 loci are associated with alcohol-related causes of CP [11].

Difficulties encountered when diagnosing CP

A frequent mistake in clinical practice is the underestimation of the fact that the diagnosis of CP should be based on three main components:

- the actual diagnosis of CP, identification of complications and prognosis of disease outcomes;

- establishing the etiology of the disease, if there is insufficient information, determining the timing of dynamic examinations, in the absence of an established etiological factor, the diagnosis in the current period of time should be interpreted as idiopathic (unclear etiology) pancreatitis; in this case, pathogenetic and symptomatic treatment is carried out;

- identification and treatment of concomitant pathology of the digestive organs (often) and other organs and systems (relatively rare), simulating and/or aggravating the course of CP (peptic ulcer, pathology of the biliary system, excessive growth of bacteria in the small intestine, celiac stenosis, etc.). Only taking into account all three components makes it possible to avoid global tactical errors in the management of patients, the cost of which may be his life [2].

Despite the achievements of instrumental diagnostics of CP, there are certain difficulties in determining the gold standard, which is still considered to be the data of biopsy and histological examination of pancreatic tissue. This is due both to the difficulties of obtaining biopsy material and to the interpretation of detected morphological changes, as well as when comparing them with data from endosonography, MRI and MRCP, especially when diagnosing the early stages of CP.

Despite a thorough examination, in 5–10% of patients it is not possible to accurately diagnose CP due to discrepancies between the data of imaging, endoscopic and functional research methods. Unfortunately, the correlation between morphological and functional disorders in the pancreas is often very low. Thus, in patients with severe exocrine insufficiency of the pancreas, with predominant damage to the small ducts of the pancreas, its normal structure is possible, while the results of modern imaging methods are usually normal. Therefore, diagnosing CP in the early stages and when small ducts are affected is very difficult. On the contrary, when large ducts are affected and in the later stages of CP, diagnosis is quite simple using imaging methods such as ultrasound, CT and MRI/MRCP.

Although there is currently no generally accepted consensus on the practical management of patients with CP, there are nevertheless relevant clinical guidelines from radiological and endoscopic associations that can be used in the management of patients with suspected CP. Examinations of a patient with suspected CP should be performed in an ascending manner - from non-invasive or minimally invasive to invasive diagnostic methods [6]. Patients with equivocal/borderline imaging test results or refractory symptoms should be referred to specialized centers for additional investigations such as secretin-enhanced MRI/MRCP, endosonography, ERCP and pancreatic function tests [11].

Treatment of chronic pancreatitis

Let us dwell in more detail on enzyme replacement therapy for exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). Pancreatic replacement therapy is indicated for patients with CP with EPI in the presence of clinical symptoms or laboratory signs of malabsorption. An appropriate nutritional assessment is recommended to identify signs of malabsorption.

EPI in CP is consistently associated with biochemical signs of malnutrition [11]. Indications for pancreatic enzyme replacement are classically established for steatorrhea with fecal fat excretion > 15 g/day. Since quantitative measurement of fecal fat is often difficult, the indication for enzyme replacement therapy is negative pancreatic function tests in combination with clinical signs of malabsorption or anthropometric and/or biochemical signs of malnutrition [11]. Symptoms include weight loss, diarrhea, severe flatulence, and abdominal pain with indigestion. Abnormally low markers associated with EPI and indicating enzyme replacement therapy include fat-soluble vitamins, prealbumin, retinol binding protein and magnesium [11]. If symptoms are not specific to EPI, then oral prostate enzyme therapy may be beneficial for 4–6 weeks.

Enzyme preparations of choice

Enteric-coated mini-tablets or mini-microspheres <2 mm in size are the drugs of choice for EPI. The effectiveness of pancreatic enzyme preparations depends on a number of factors: mixing with food; emptying the stomach with food; mixing with duodenal chyme and bile acids; rapid release of enzymes in the duodenum.

Pharmaceutical formulations of pancreatitis are primarily available in the form of pH-sensitive mini-tablets or enteric-coated mini-microspheres that protect the enzymes from the acidic contents of the stomach and allow them to rapidly disintegrate at pH 5.5 in the duodenum to release the enzymes. Oral pancreatic enzymes should be taken with food. Although enzyme preparations include large amounts of pancreatic enzymes for digestion, the dosage of enzymes in replacement therapy is based on lipase activity. The recommended starting dose is approximately 10% of the physiologically secreted dose (PSD) of lipase in the duodenum after a normal meal under physiological conditions. This means that a minimum lipase activity of 30,000 IU is required to digest normal food. Since 1 IU of lipase is equal to 3 FSD, the minimum amount of lipase required to digest normal food is 90,000 FSD (endogenous secretion of enzymes and orally administered enzymes taken together) [11].

The effectiveness of enzyme replacement therapy can be adequately assessed by changes in symptoms associated with digestive disorders (eg, steatorrhea, weight loss, flatulence) and normalization of the patient's nutritional status.

The enzyme drug Pangrol has been successfully used in enzyme replacement therapy for CP. The release form of the drug is mini-tablets coated with an acid-resistant coating and enclosed in a capsule. Mini-tablets are coated with an acid-resistant coating - they do not collapse in the stomach, which guarantees the activity of enzymes in the duodenum. Each capsule contains a standardized number of mini-tablets based on the enzymatic activity of pancreatin. Dissolving in the stomach, the capsule releases mini-tablets, which, due to their equally small size, are evenly distributed in the contents of the stomach. The shell of Pangrol mini-tablets is resistant to the acidic environment of the stomach, and its dissolution occurs only in a neutral and slightly alkaline environment. Thus, the release of enzymes occurs after the chyme with mini-tablets enters the duodenum. Compared to mini-microspheres, Pangrol mini-tablets provide a more complete release of enzymes - over 95% [12]. The production technology ensures a gradual/layer-by-layer release of enzymes, due to which a high concentration is maintained for a long time. Pangrol lipase activity persists for more than one hour [12].

The drug Pangrol is available in two dosages - 10,000 units (about 20 mini-tablets in one capsule) and 25,000 units (about 50 mini-tablets in one capsule). Each mini-tablet of the drug contains 500 IU of lipase, which makes it possible to individually select the dosage for patients (especially children).

The drug Pangrol is an innovative dosage form that provides maximum pharmacotherapeutic benefits:

- the coating of mini-tablets is resistant to acidic pH and prevents inactivation of the pancreatic enzyme complex;

- production technology makes it possible to achieve a uniform concentration of enzymes at the site of application;

- ensures high availability of the pancreatin complex;

- mini-tablets release the maximum dose of lipase;

- effective pharmaceutical availability guarantees adequate bioavailability and clinical effect.

Thus, the use of modern drugs that combine acid resistance, simultaneous pyloroduodenal transit with chyme, rapid activation, and a high content of proteases is the key to successful treatment and improvement of the quality of life of patients with CP. To achieve the maximum effect of enzyme replacement therapy, the optimal dose of the drug should be selected. Patients with persistent symptoms of EPI despite taking maximum doses of enteric-coated enzyme preparations should add proton pump inhibitor therapy.

Literature

- Maev I.V., Kucheryavyi Yu.A., Andreev D.N., Dicheva D.T., Gurtovenko I.Yu., Baeva T.A. Chronic pancreatitis: new approaches to diagnosis and therapy. Educational and methodological manual for doctors. M.: FKUZ "GKG Ministry of Internal Affairs of Russia", 2014. 32 p.: ill. 3.

- Maev I.V., Kucheryavyi Yu.A., Samsonov A.A., Andreev D.N. Difficulties and errors in the management of patients with chronic pancreatitis // Ter. archive. 2013, no. 2, p. 65–72.

- Etemad B., Whitcomb DC Chronic pancreatitis: diagnosis, classification, and new genetic developments //Gastroenterology. 2001. 120. P. 682–707.

- Lopatkina T.N. Conservative treatment of chronic pancreatitis in an outpatient setting // Treating Doctor. 2004, no. 6.

- Nair RJ, Lawler L., Miller MR Chronic Pancreatitis // Am Fam Physician. 2007; 76:1679–1688.

- Duggan SN, Ní Chonchubhair HM, Lawal O., O'Connor DB, Conlon KC Chronic pancreatitis: A diagnostic dilemma // World J Gastroenterol. 2016; 22(7):2304–2313.

- Conwell DL, Bechien U. Chronic Pancreatitis: Making the Diagnosis // Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012. 10. P. 1088–1095.

- Iglesias-Garcia J., Domínguez-Muñoz JE, Castiñeira-Alvariño M., Luaces-Regueira M., Lariño-Noia J. Quantitative elastography associated with endoscopic ultrasound for the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis // Endoscopy. 2013; 45: 781–788.

- Dominguez-Muñoz JE, Iglesias-Garcia J., Castiñeira Alvariño M., Luaces Regueira M., Lariño-Noia J. EUS elastography to predict pancreatic exocrine insufficiency in patients with chronic pancreatitis // Gastrointest Endosc. 2015; 81: 136–142.

- Rana SS, Vilmann P. Endoscopic ultrasound features of chronic pancreatitis: A pictorial review // Endoscopic ultrasound. 2015, v. 4, p. 10–14.

- United European Gastroenterology evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of chronic pancreatitis (HaPanEU) // United European Gastroenterol J. 2022, Mar; 5 (2): 153–199.

- Kolodziejczyk MK, Zgoda MM Eurand Minitabs - the innovative application formula of a pan-creatic enzyme complex (Pangrol 10,000, 25,000) // Polimery w medycynie. 2010; 40 (2): 21–28.

T. E. Polunina, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

GBOU VPO MGMSU im. A. I. Evdokimova Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, Moscow

Contact Information

Chronic pancreatitis: exocrine insufficiency and its correction T. E. Polunina For citation: Attending physician No. 6/2018; Page numbers in the issue: 71-77 Tags: enzymes, replacement therapy, gastrointestinal tract, diagnostics

Etiology

Currently, the main pathophysiological reasons causing the development of EPI are considered to be: 1) limitation of enzyme production, which may be due to underdevelopment or damage to the pancreatic parenchyma; 2) increasing the rate of lipase degradation; 3) decreased perception of factors that stimulate the mechanisms of production of pancreatic enzymes; 4) impaired delivery of pancreatic enzymes to the duodenum due to obstruction of the pancreatic ducts or excretory viscosity; 5) low level of activation of pancreatic enzymes in the cavity of the duodenum (Table 1).

However, clinical symptoms of EPI appear when the level of lipase in the contents of the duodenum is less than 5–10% of the normal concentration [12, 13, 21, 23].

Dosing for cystic fibrosis

The initial dose of drugs containing pancreatic enzymes for children with cystic fibrosis depends on the age and degree of EPI (Table 2).

The dose is selected individually according to the severity of the disease and under the control of steatorrhea and proper nutrition. In most cases, the maintenance dose should not exceed 10,000 IU of lipase per 1 kg of body weight per day or 4,000 IU of lipase per gram of fat consumed. The use of modern microgranular pancreatic preparations with an enteric coating makes it possible to ensure the effectiveness of the treatment of malabsorption in cystic fibrosis in children (evidence level 2a). Donation therapy with pancreatic drugs prevents delays in physical development in children with cystic fibrosis (level of evidence 1b) [10, 22, 27, 29, 30].

Indications for the use of pancreatic enzymes

In adult patients with EPI, the indication for prescribing drugs containing pancreatic enzymes is a combination of weight loss with steatorrhea of 15 g per day with a daily diet containing at least 100 g of fat. However, it has been shown that in patients with EPI, subclinical steatorrhea is an indication for the administration of pancreatic enzymes [16, 28].

In children, the presence of clinical or laboratory signs of EPI obliges the doctor to prescribe subsidized therapy using pancreatic enzymes. Children with chronic pancreatitis, which is accompanied by pain, are advised to prescribe drugs containing pancreatic enzymes, even without documented signs of EPI (level of evidence 1b) [26].

Classification

There are primary EPI, which develops as a result of congenital diseases of the pancreas, and secondary EPI. Among the pediatric population, secondary EPI is more common. According to G.V. Rimarchuk and T.K. Tyurina, in children with gastroduodenal pathology, EPI occurs in 41.8%, with diseases of the hepatobiliary system - in 42.2%, with various diseases of the small intestine - in 38–88% of cases [6]. The provoking factors for the development of secondary EPI are most often chronic diseases of the digestive tract, poor diet (intake of excess food).

There is also a distinction between absolute and relative EPI. Absolute EPI is characterized by an absolute deficiency in the production of pancreatic enzymes, relative EPI is a discrepancy between the volume of food and the level of excreted enzymes or a violation of the process of activation of pancreatic enzymes in the lumen of the duodenum.

Relative EPI may be caused by a decrease in pH < 5.5 in the duodenal lumen, impaired motility of the small intestine, which is accompanied by rapid transit of contents, with a deficiency of bile acids and enterokinase deficiency in the duodenal lumen, and excessive bacterial growth in the small intestine [7].

Clinic

The leading clinical syndromes of EPI are the pancreagenic form of malabsorption, dyspeptic syndrome, and trophic disorders.

The pancreatic form of malabsorption is characterized by a decrease in body weight with sufficient caloric content and quality of food, flatulence, sometimes pain, and an increase in the volume of feces. Feces are usually gray in color, putty-like consistency, with a shiny surface and increased stickiness. Laboratory testing reveals a high content of neutral fat in the feces and hypercarotenemia.

Dyspeptic syndrome is manifested by decreased appetite, in some cases even to the point of anorexia, recurrent vomiting, flatulence and flatulence, and stool instability.

Violation of trophism - dry skin, the presence of hangnails, decreased physical activity, increased fatigue, lag in weight gain.

Drug treatment

The main goal of drug therapy for EPI is subsidized compensation for the deficiency of pancreatic enzymes to restore the digestion of food ingredients. Therapy for EPI is based on the oral administration of exogenous porcine pancreatic enzymes. The level of activity of pancreatic enzymes obtained from the porcine pancreas is approximately 30–50% higher than those obtained from the cow pancreas [32].

The following groups of drugs containing pancreatic enzymes are distinguished:

— extracts of the gastric mucosa, the main active ingredient of which is pepsin (acidin-pepsin);

- pancreatin preparations, the main enzymes of which are lipase, amylase, proteases (Pangrol®, Creon, Pancreatin, Mezim Forte, Panzinorm);

- a combination of pancreatin with additional components: with bile components, hemicellulose (festal, digestal, enzystal), with simethicone (pepzym, pancreoflate, enzymetal);

— preparations based on plant enzymes (enzymtal, pepzym, oraza, solisim, etc.);

- drugs - combinations of pancreatin with plant enzymes: pancreatin + rice fungus extract (combicin) [5].

Choice of drug

Currently, only drugs are used that contain pancreatic extract in encapsulated form - in microtablets or mini-microspheres with a pH-sensitive enteric coating, which protects the pancreatic enzymes contained in it from destruction by gastric juice [20]. One of these drugs is Pangrol®. In this drug, pancreatic enzymes are contained in mini-tablets enclosed in an enteric coating. Pangrol® 10000 contains lipase (10,000 IU), amylase (9500 IU), protease (500 IU), Pangrol® 20000 - lipase (20,000 IU), amylase (12,000 IU), protease (900 IU); Pangrol® 25000 - lipase (25,000 IU), amylase (22,500 IU), protease (1250 IU). The therapeutic activity of the drug is determined by the enzymatic activity of lipase and trypsin; amylolytic activity is important only in the treatment of patients with cystic fibrosis [24].

Dosing

The dose of the drug is individual for each patient and depends on the degree of indigestion and the composition of the food taken.

The recommended starting dose for children under 4 years of age is 1000 IU of lipase per 1 kg of body weight per day, and for children over 4 years of age - 500 IU or 500 units of lipase per gram of fat in the daily amount of food. For school-age children and adolescents, 10,000–25,000 IU per meal is recommended, for which use 1–2 capsules of Pangrol® 10000 (10,000–20,000 IU lipase) or 1 capsule of Pangrol® 20000 (20,000 IU lipase). The choice of dose of pancreatic enzymes is based on the fact that after eating for 20–60 minutes, the secretion of pancreatic enzymes increases almost 6 times, then gradually decreases. But after eating for 3–4 hours, their concentration in the small intestine is 3 times higher than before food stimulation [23]. It is not recommended to exceed a dose of 10,000 IU of lipase per 1 kg of body weight per day [18, 25]. None of the commercial enzyme preparations, after oral administration, is capable of delivering so many pancreatic enzymes into the lumen of the duodenum that the level of active lipase corresponds to that (more than 360,000 IU) that is provided by a healthy pancreas under physiological conditions. However, subsidized therapy with drugs containing pancreatic enzymes significantly improves the digestion and absorption of fat [9]. This effect, according to J. Enrique Domínguez-Muñoz [13], can only be achieved using modern drugs with a pH-sensitive enteric coating.

Treatment

Diet

When prescribing a diet for patients with EPI, consultation with a nutritionist is recommended. The calorie content and volume of food should be age appropriate. The daily amount of food is divided into six or more meals. Reducing the volume of a single meal helps the digestion process. Currently, it is not recommended to limit fat in the diet of patients with EPI, since the normal functioning of lipase during the transit of food through the intestines requires the presence of triglycerides [13, 26].