Infectious disease specialist

Sinitsyn

Olga Valentinovna

34 years of experience

Highest qualification category of infectious disease doctor

Make an appointment

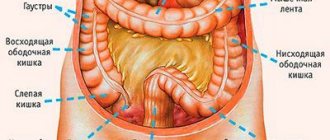

Dysentery is an acute disease accompanied by a disorder of the large intestine as a result of the aggressive action of Shigella bacteria.

Penetrating into the human body with food or drinking water, Shigella bacteria pass through the digestive organs and become established in the mucous membrane of the large intestine. By their presence, they provoke an inflammatory reaction, resulting in a disruption of the normal balance of the local flora.

Symptoms of the disease

The first symptoms of dysentery can appear immediately (a day after bacteria enter the body) or after a week. In most cases, the patient begins to notice problems in the body after 2-3 days.

Signs of colitic dysentery begin quite aggressively: body temperature rises sharply to 40-41 degrees, appetite almost completely disappears. The sick person may feel nausea that turns into vomiting. Cutting pains are felt in the abdomen, painful diarrhea appears (often mixed with mucus, pus and blood).

The doctor who arrives for examination reveals the following indicators:

- tachycardia;

- low blood pressure;

- possible whitish coating on dry tongue.

This variety is characterized by a decrease in the intensity of symptoms by the 6-7th day of the disease. However, if the patient has suffered a severe form of the disease, then he may experience slight clouding of mind, frequent bowel movements (up to 20-30 drops per day), and extremely severe pain in the abdominal area.

Manifestations of the gastroenteric variety of dysentery begin 6-8 hours after infection and are characterized by profuse vomiting and repeated bowel movements. The patient may experience intense attacks of pain around the navel area. Possible dehydration. The symptoms manifest themselves extremely actively, but do not last long.

It is possible to diagnose the erased form of this disease, which is the most common type today. It is characterized by mild pain in the abdominal area, general physical discomfort, and mushy stool consistency (1-2 times a day). If symptoms persist for a long time, the doctor makes a diagnosis of chronic dysentery (this does not happen often).

Are you experiencing symptoms of dysentery?

Only a doctor can accurately diagnose the disease. Don't delay your consultation - call

Diagnostics

If you have symptoms of the disease, it is recommended to consult a doctor. An upset stomach and intestines is a reason to visit a gastroenterologist's office, especially if it occurs on a regular basis. A specialist will be able to make an accurate diagnosis after conducting a comprehensive diagnosis, which includes interviewing the patient, visual examination, passing the necessary tests and undergoing diagnostic procedures. Based on the data obtained, the doctor will be able to accurately make a diagnosis.

Treatment of the disease

Inpatient treatment of dysentery is carried out in extremely rare cases in severe forms of the disease, as well as when it is detected in the elderly and children of the first year of life.

All patients with pronounced loose stools and elevated body temperature are advised to undergo strict bed rest and adherence to a diet for dysentery (table No. 4 is shown first, and subsequently No. 13).

Depending on the characteristics of the disease, a course of antibacterial drugs is prescribed: for any form except mild ones). To prevent antibiotics from provoking an even more serious disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, they are paired with eubiotics (the course of taking them is 3-4 weeks, regardless of the number of days of taking antibiotics).

Drug therapy includes taking drugs that stimulate the absorption of beneficial substances, including enzyme agents. Antispasmodics, enterosorbents, as well as drugs that stimulate the protective functions of the immune system may be additionally recommended.

Having stopped the acute stage, the doctor can prescribe microenemas that improve the condition of the intestinal mucosa, based on rose hips, sea buckthorn, and eucalyptus.

SHIGELLOSES (dysentery)

Dysentery is one of those few infectious diseases that have not only been known to mankind since antiquity, but also still retain their original name. Hippocrates used the term “dysentery” to describe a clinical syndrome characterized by diarrhea and abdominal pain. It is quite natural that completely different diseases were hidden under this definition. The term closest to the modern definition of dysentery is sekiri (“red diarrhea”), which was common in China and Japan and was used to describe diseases characterized by loose stool mixed with mucus, blood, and pain during bowel movements.

In 1875, the Russian doctor F.A. Lesh managed for the first time to detect amoebas in the stool of patients with dysentery. It was surprising that, despite frequent epidemics of dysentery at the end of the 19th century, it was not possible to identify amoebas in the stool of patients either in Europe or in Japan. Although the bacterial etiology of dysentery was assumed in these cases, no one was able to diagnose it for a long time. Only in 1898, the Japanese researcher Kiyoshi Shiga isolated a bacillus from the feces of patients, which was recognized as the causative agent of bacterial dysentery. Due to the establishment of different etiologies of dysentery, in the first half of the twentieth century the terms “bacillary” and “amoebic” dysentery were used in the medical literature. Currently, dysentery refers only to diseases caused by Shigella.

In terms of prevalence, acute intestinal infections (AI) are second only to respiratory viral diseases. Recent decades have been marked by certain advances in the study of the etiopathogenesis of acute intestinal infections. If before 1970, only 10% of hospitalized patients had an established etiology of the disease, then by the end of the twentieth century this figure increased to 50-60%. Despite the identification of new pathogens of acute intestinal infections, shigellosis continues to occupy a significant position in the etiological structure of acute infectious diarrheal diseases. According to the Federal Center for State Sanitary and Epidemiological Surveillance, in Russia in 2002, 80,500 cases of dysentery were registered (incidence rate 55.96 per 100 thousand population), of which children under 14 years old accounted for 38,5000 (incidence rate 159.1 per 100 thousand). ). In the USA, according to the National Committee for Infectious Disease Control (CDC), from 25 to 30 thousand cases of shigellosis are registered annually with an incidence rate for children from one to four years old - 27 per 100 thousand population, and for persons over 20 years of age - 2.6 per 100 thousand.

Etiology. Since 1930, bacilli isolated from dysentery patients have been officially grouped into the genus Shigella, family Enterobacteriaceae. Shigella are identified by their biochemical and antigenic properties (O - antigens), according to which four groups of Shigella are distinguished (see Table 1).

| Table 1. Classification of Shigella. |

According to their morphological properties, Shigella are non-motile, gram-negative bacteria. The common and most important property of all representatives of the genus Shigella is invasiveness, i.e. the ability of bacteria to invade intestinal epithelial cells with subsequent reproduction and parasitism in them. Different types of Shigella differ greatly in their initial biological properties, which, in fact, determines the degree of their virulence and pathogenicity for humans. Sh. have the highest virulence. dysenteriae 1, which is primarily due to their ability to produce one of the most powerful natural toxins - Shiga toxin. Some other Shigella species are also capable of producing Shiga-like toxins, but with significantly lower activity. Exceptionally high virulent properties of Sh. dysenteriae 1 determine an extremely low infectious dose, which is only tens or hundreds of microbial cells. For other Shigella species, the infectious dose is determined to be one to two orders of magnitude higher.

Shigella is relatively resistant to environmental factors and can survive on household items for a long time; in water they remain viable for up to two to three weeks, and in a dried and frozen state for up to several months. High temperatures, on the contrary, contribute to their rapid death: at a temperature of +60°C - within 10 minutes, and when boiling - instantly. Shigella exhibits fairly high sensitivity to disinfectants, ultraviolet and direct sunlight.

Epidemiology. Shigellosis refers to classic anthroponotic intestinal infections, which are characterized by a fecal-oral transmission mechanism of infection, realized by all possible routes for this mechanism - food, water and contact. However, the practical implementation of each of these transmission routes depends on many factors and conditions (type of Shigella, age of the patient, his premorbid background, etc.). Since Sh. are the most virulent. dysenteriae 1, it is for them that the contact route of transmission of infection is most characteristic, although this route can also be realized by other types of Shigella, especially in young children, elderly and weakened patients. Numerous observations indicate that in case of group cases of diseases, certain types of Shigella have their own, most typical route of infection transmission (contact for group A, food for group D and water for groups B and C). In recent years, sexual transmission of shigella infection among homosexuals has been described (1). In particular, during an outbreak of shigellosis caused by Sh. sonnei (biotype G), in one of the clubs in New South Wales (Australia) between January 1 and July 31, 2000, 148 cases were registered, 80% of whom were homosexuals [2].

Despite the diversity of shigellosis pathogens, Sh. has the greatest epidemic significance for most countries of the world. flexneri and Sh. sonnei. Although Shigella is widespread (an anthroponotic infection), the highest incidence rates are recorded in countries and regions with poor sanitation and high population density, which greatly facilitates the possibility of transmission of the pathogen from person to person. According to estimates, about 140 million cases of shigellosis are registered annually in the world. Susceptibility to shigella infection varies among individuals of different age groups. Children under two or three years of age are most susceptible to them.

Pathogenesis. The basis of the pathogenesis of infectious diseases is the characteristics and nature of the interaction of microbes not only with the cells of the macroorganism, but also with the nonspecific and specific defense systems of the body.

Shigella has quite pronounced virulent properties, as a result of which the disease can develop even with a low infectious dose (in comparison with enteropathogenic bacteria such as salmonella and E. coli). Due to the relative resistance to the action of gastric juice and bile acids, Shigella, without losing its virulence, passes through the gastric barrier and the proximal parts of the small intestine. In the pathogenesis of the disease, small and large intestinal phases are distinguished, the severity of which ultimately determines the course of the disease. In patients with the typical, colitic variant of acute dysentery, the small intestinal phase is not clinically manifested at all, and the disease initially manifests itself as damage to the distal colon. The small intestinal phase is usually short-lived and limited to two to three days. The primary translocation of Shigella through the epithelial barrier is carried out by specialized M cells capable of transporting both the bacteria themselves and their antigens into the intestinal lymphatic formations (follicles, Peyer's patches) with their subsequent penetration into epithelial cells and resident macrophages. Toxic substances released during the translocation of Shigella (exo- and endotoxins, enterotoxins, etc.) initiate the development of intoxication syndrome [3], which in shigellosis always precedes the development of diarrhea syndrome.

The key factor in the virulence of Shigella is their invasiveness, i.e., the ability to penetrate intracellularly, reproduce and parasitize in the cells of the colon mucosa (mainly in the distal section) and resident macrophages of the lamina propria (see Figure 1). Through macrocytopinosis, Shigella penetrates the cytoplasm of epithelial cells, where they very quickly lyse the phagosomal membrane, which leads to cell damage and death. Subsequent spread of Shigella occurs through the basolateral membranes of epithelial cells. Damage and destruction of epithelial cells are accompanied by the development of inflammatory infiltration of polymorphonuclear leukocytes of the lamina propria, the formation of ulcers and erosions of the colon mucosa, which is clinically manifested by the development of exudative-type diarrhea. The ability for invasion and intracellular reproduction of Shigella is encoded by genetic mechanisms, the expression of which occurs only under in vivo conditions. Despite their invasiveness, Shigella is not capable of deep spread, which is why systemic dissemination of the pathogen during shigellosis, as a rule, does not occur (with the exception of Sh. dysenteriae 1).

Intestinal motility is an important protective mechanism that limits and prevents the attachment and invasion of Shigella to epithelial cells, which is clearly demonstrated by the prolongation and severity of the infectious process in individuals receiving drugs that suppress intestinal motility.

The dysbiotic changes in the composition of the normal microflora of the large intestine observed in patients with shigellosis have a significant impact on the rate of mucosal repair in the convalescence stage and restoration of the functional activity of the intestine.

After suffering from the disease, patients develop short-term (up to one year) type- and species-specific immunity, due to which reinfection is possible.

Clinic. The clinical picture of shigellosis is very variable, which is reflected in the applied clinical classification of the disease (see Table 2). Although it is believed that Sh. sonnei, as less virulent strains of Shigella, often cause milder forms of the disease, it should be remembered that the etiology of shigellosis only predetermines, but does not determine the characteristics of the course of the disease in specific patients (in terms of form, variant and severity).

The chronic form of dysentery is currently quite rare and, according to the literature, does not exceed 1-2% of cases, although there is an opinion that such a low proportion of it may be due to insufficiently developed diagnostic criteria. Much more often, doctors in their practice encounter acute forms of shigellosis, which are of the greatest interest in terms of an adequate assessment of the clinical picture of the disease detected in the patient, the completeness of the examination, the correctness and timeliness of the therapy.

The incubation period for shigellosis can vary from 8-12 hours (with the gastroenteric variant) to five days (with the colitis variant of the disease), averaging two to three days.

A typical course of acute dysentery is colitis, its characteristic feature is the acute onset of the disease with the development of an intoxication syndrome: a rise in body temperature, chills, fever, weakness, a feeling of weakness, headache, and loss of appetite. With this variant of acute dysentery, intoxication syndrome always precedes clinical manifestations of intestinal damage. Only after some time (from 2-3 to 12-18 hours) do patients show signs of damage to the gastrointestinal tract. Initially, patients note the occurrence of diffuse, dull pain, which over time becomes more acute and acquires a cramping character. The localization of pain most often corresponds to the projection area of the distal colon (lower abdomen and left iliac region). Almost simultaneously with abdominal pain, patients note the appearance of diarrhea. For the colitic variant of dysentery, the relationship between the development of an attack of abdominal pain and defecation, the urge to which appears at the height of a painful attack, is typical. Since abdominal pain is caused by spastic contraction of the intestine (increased intestinal motility), the first bowel movements are relatively abundant, but quite quickly they decrease in volume (“scanty stool”), lose their fecal character, and pathological impurities appear in them - mucus and blood. As a rule, bowel movements occur more than five times a day (often up to 15–20 or more). Quite often, patients experience tenesmus, and in more severe cases, false urges. An objective examination of patients reveals a painful and spasmodic sigmoid colon.

If mucus in the stool is a typical sign of acute dysentery, then blood may be present in microscopic quantities and can only be detected during coprocytoscopic examination. Visualized blood in the stool is determined in the form of streaks. In more severe cases of the disease, defecation may result in the release of a small amount of mucus streaked with blood.

Criteria for the severity of the course of the colitic variant of acute dysentery are the severity of the intoxication syndrome and the nature of the damage to the distal mucosa of the large intestine (see Table 3). Severe dehydration in patients with the colitic variant of acute dysentery is not detected due to the absence of vomiting and scanty stool.

The gastroenterocolitic variant of dysentery is also characterized by an acute onset of the disease: with chills, fever, headache and the simultaneous appearance of gastroenteritis syndrome - spastic pain in the epigastric region, nausea, vomiting, loose watery stools. Clinical signs of colitis are usually absent on the first day of the disease and appear only after one to three days, which corresponds to the pathomorphological stages of damage to the gastrointestinal mucosa. Depending on the frequency of vomiting and the intensity of diarrhea syndrome, patients show signs of dehydration quite early (dry mucous membranes of the oropharynx, pale skin and cyanosis, pointed facial features, decreased blood pressure, oliguria, etc.). From the moment the pathological process spreads to the mucous membrane of the large intestine, the manifestations of gastroenteritis gradually stop: vomiting stops, the volume of bowel movements decreases, and pathological impurities (mucus and blood) appear in the stool. Depending on the nature of the damage to the mucous membrane of the distal colon, patients may notice the appearance of tenesmus and false urges. When palpating the abdomen in the first days of the disease, rumbling along the course of the large intestine is noted, and in subsequent days pain and spasm of the sigmoid colon appears and increases.

The severity of the gastroenterocolitic variant of dysentery is determined based on the severity of intoxication and dehydration of the body. In most cases it does not exceed grades II-III.

A rare variant of the course of acute dysentery is gastroenteric, characterized by great similarity with foodborne toxic infections.

Complications. Although the risk of complications is highest in patients with dysentery caused by Sh. dysenteriae 1, at the present stage there is a clear tendency towards an increase in severe forms of dysentery caused by other types of Shigella (in particular, Sh. flexneri), which, accordingly, affects the possibility of developing complications. The most dangerous complications include: infectious-toxic shock; intestinal perforation with the development of peritonitis; encephalic syndrome (fatal encephalopathy syndrome or Ekiri syndrome), which predominantly develops in children and immunocompromised patients with dysentery caused by Sh. sonnei or Sh. flexneri; bacteremia detected in dysentery Sh. dysenteriae 1 in 8% of cases and extremely rarely - when infected with other types of Shigella (in children under one year old, weakened, depleted and immunocompromised patients); hemolytic-uremic syndrome, developing a week from the onset of the disease and characterized by microangiopathic hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia and acute renal failure. Often, patients may develop complications associated with the activation of secondary microflora: pneumonia, otitis, urinary tract infections, etc. Rare but probable complications include reactive arthritis and Reiter's syndrome (about 2% of patients expressing HLA-B27). In recent years, the possible role of shigellosis in the formation of irritable bowel syndrome has been discussed.

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. Specific diagnosis of shigellosis is based on the isolation and identification of Shigella from the patient's feces and conducting serological and/or immunological studies aimed at detecting Shigella antigens or antibodies to them. Without laboratory confirmation, the diagnosis of dysentery can only be established with a typical clinical picture.

Although the diagnostic value of endoscopic examination of the colon (sigmoidoscopy and fibrocolonoscopy) in patients with suspected shigellosis is limited, the information obtained during its implementation allows: a) to objectively assess the nature of the damage to the colon mucosa; b) carry out differential diagnosis and c) monitor the effectiveness of the therapy.

Depending on the nature of the lesion, the following variants of proctosigmoiditis are distinguished: catarrhal, catarrhal-hemorrhagic, erosive, erosive-ulcerative and fibrinous, which, as a rule, correspond to the severity of the disease.

When carrying out differential diagnosis, it is first necessary to exclude other acute intestinal infectious diseases, for which the development of exudative diarrhea is typical, namely enteroinvasive escherichiosis, salmonellosis, yersiniosis (Y. enterocolitica), campylobacteriosis (Campylobacter jejuni), Clostridium difficile infection and amebiasis (protozoal disease , caused by Entamoeba histolytica). In addition, it must be remembered that diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease can debut under the guise of shigellosis.

Treatment . Treatment of patients with dysentery can be carried out not only in a specialized infectious diseases department, but also on an outpatient basis, which is determined by clinical and epidemiological indications. First of all, patients with moderate and severe forms of the disease should be hospitalized, with a protracted and chronic course - patients with severe concomitant diseases, children under one year old and the elderly, as well as persons posing an epidemic danger (regardless of the variant and severity of the disease) - workers food enterprises and persons equated to them.

Given the nature of the damage to the intestinal mucosa, patients with dysentery, especially during the acute period of the disease, need strict adherence to therapeutic nutrition. Any foods that have an irritating (mechanical, chemical, etc.) effect should be excluded from the diet. Due to lactose deficiency developing in patients, whole milk is excluded from the diet. The expansion of the diet is carried out gradually, only as the patient recovers. And yet, the transition to normal nutrition should be carried out no earlier than complete recovery, characterized by repair of the mucous membrane (see Table 3).

Since antibacterial therapy has always been recommended for the treatment of patients with dysentery, a serious problem today is the development of resistance to antimicrobial drugs in Shigella, especially in those countries where they are sold over-the-counter and self-medicated [5]. Recently conducted studies in our country [6] confirmed the high frequency of resistance in Sh. flexneri and Sh. sonnei to cefotaxime (96.6 and 94.2%, respectively), tetracycline (97.7 and 92.8%), chloramphenicol (93.2 and 50.7%), ampicillin (95.5 and 26.1) and ampicillin/sulbactam (95.5 and 23.2%). Resistance was not detected only to ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin and nalidixic acid.

The choice of antimicrobial drug and the regimen for its use in patients with dysentery are determined by the type and severity of the disease. With the gastroenteric variant, antimicrobial therapy is not indicated and patients are prescribed only pathogenetic therapy. For mild colitic and gastroenterocolitic variants of dysentery, it is advisable for patients to be prescribed furazolidone 0.1 g four times a day or nalidixic acid (nevigramon) 0.5-1.0 g four times a day for three to five days. The most effective drugs for treating patients with moderate and severe dysentery are fluoroquinolone drugs (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin, etc.), third generation cephalosporins (cefotaxime), which are prescribed in general therapeutic doses for five to seven days. In severe cases, combined antibacterial therapy (fluoroquinolones and aminoglycosides; cephalosporins and aminoglycosides) can be carried out.

In addition to antibacterial therapy, an important place in the treatment of patients with dysentery is occupied by pathogenetic treatment, including detoxification and rehydration. In the acute period of the disease, it is advisable for patients to be prescribed desmol and smecta, which have an anti-inflammatory and membrane-stabilizing effect on the intestinal mucosa. After relief of the intoxication syndrome, patients are shown drugs that normalize the processes of digestion and absorption (digestal, mezim-forte, panzinorm, festal, cholenzym, oraza, etc.). Correction of intestinal microbiocenosis should be carried out only during the period of convalescence, when the acute inflammatory reaction is stopped. During the same period, patients are shown physiotherapeutic procedures that accelerate the process of repair of the colon mucosa.

Literature

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Shigella sonnei outbreak among men who have sex with men-San Francisco, California, 2000-2001.//MMWR Morb.Mortal.Wkly.Rep.-2002.-v.50.-No. 922.

- Pontivivo G., Karagiannis T., Marriott D. et al. Shigellosis Linked to Sex Venues, Australia.//Emerging Infectious Diseases.- 2002.- v. 8.-No. 8.-r. 862-864.

- Malov V. A., Pak S. G. Medical and biological aspects of the problem of intoxication in infectious pathology // Therapeutic archive. - 1992.- No. 11. - With. 7-11.

- Khalil K., Khan S., Mazhar K et al. Occurrence and susceptibility to antibiotics of Shigella sp. in stool of hospitalized children with bloody diarrhea in Pakistan.//Am.J.Trop.Med.Hyg.-1998.-v.58.-p.800-803.

- Strachunsky L. S., Krechikova O. I., Ivanov A. S. et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Shigella in the Smolensk region in 1998-1999 // Clinical microbiology and antimicrobial therapy. - 2000. - T. 2. - No. 2. — pp. 65-69.

V. A. Malov, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor A. N. Gorobchenko, Candidate of Medical Sciences MMA named after. THEM. Sechenov

Note!

- According to the Federal Center for State Sanitary and Epidemiological Surveillance, in Russia in 2002, 80,500 cases of dysentery were registered (incidence rate 55.96 per 100 thousand population), of which children under 14 years old accounted for 38,5000 (incidence rate 159.1 per 100 thousand). ).

- Despite the identification of new pathogens of acute intestinal infections, shigellosis continues to occupy a significant position in the etiological structure of acute infectious diarrheal diseases.

- Since 1930, bacilli isolated from dysentery patients have been officially grouped into the genus Shigella, family Enterobacteriaceae.

How to distinguish dysentery from other intestinal disorders?

Dysentery can resemble other intestinal diseases, so it is important to know their main differences:

- Salmonellosis and food poisoning.

The disease begins with frequent vomiting, which is repeated several times. The pain is concentrated in the epigastric region. Spasms on the left side of the abdomen do not occur, since the colon is not affected by food poisoning. There is also no tenesmus. When a patient develops salmonellosis, the stool takes on a greenish tint, reminiscent of the appearance of swamp mud.

- Amoebiasis.

With amoebiasis, the disease does not have such pronounced symptoms as with dysentery. Body temperature may rise, but only slightly. Blood and mucus will be present in the stool; in appearance they resemble raspberry jelly. When analyzing the secretions, it will be possible to detect a huge number of amoebas.

- Cholera.

The first symptoms of cholera are: diarrhea, profuse vomiting, slight increase in body temperature, tenesmus. The stool is liquid and resembles rice water in appearance. Symptoms of dehydration develop quickly, which significantly worsens the course of the disease.

- Typhoid fever.

With this disease, spastic colitis develops, body temperature rises to significant levels, and it persists for a long time. A roseola-type rash appears on the skin.

- Colitis.

The disease is non-infectious in nature. Occurs against the background of intoxication of the body with chemicals. In addition, colitis can be a companion to gastritis, cholecystitis, uremia, and diseases of the small intestine. Exacerbation of colitis does not depend on the time of year, the disease is not contagious, and does not lead to pronounced changes in the organs of the digestive system.

- Haemorrhoids.

The patient discharges blood from the anus, but the large intestine does not become inflamed. Blood appears only at the end of the act of defecation.

- Rectal cancer.

Symptoms of intoxication of the body occur only during the disintegration of the tumor. During the same period, blood appears and diarrhea develops. Oncopathologies do not have an acute course; they metastasize to other organs and lymph nodes.

How is dysentery transmitted?

The causative agent of dysentery is a sick person, who poses a danger to other people from the very beginning of infection, since the release of pathogens at a given moment in time is the most rapid, so this point should be given due attention, which many, unfortunately, do not do.

How is dysentery transmitted : fecal-oral (bacteria from an infected person penetrate the gastrointestinal tract of a healthy person, provoking the development of pathology).

Today, there are several ways of transmitting the pathogen:

- contact-domestic – lack of following basic rules of behavior,

- food - when consuming those products that contain a lot of the above-mentioned bacteria,

- aqueous – the presence of a high content of bacteria in the liquid.

Basic measures to prevent the occurrence of dysentery

- Follow basic rules of personal hygiene to eliminate the source of infection for dysentery : wash your hands with soap and water.

- Be sure to monitor the shelf life of food products.

- Do not buy or consume food past its expiration date.

- Do not purchase food from unregistered places of sale.

- Be sure to wash food before consumption.

- Do not use water from sources that are not suitable for drinking as a means of drinking, because dysentery infection occurs through them. Drink exclusively boiled or bottled water.

- Be careful when swimming in public places.

Now you know how dysentery infection occurs .

Classification according to ICD-10

For the described shigillosis, represented by different types, a three-character heading has been conditionally created. It contains the following subspecies:

- A03.0 - pathology caused by Shigella dysenteriae, belongs to group “A” and is called Shiga-Kruse dysentery;

- A03.1 – disease with a pathogen in the form of Shigella flexneri, group “B”;

- A03.2 – a disease caused by the bacterium Shigella boydii, belongs to group “C”;

- A03.3 – disease from Shigella sonnei, group “D”;

- A03.9 – unspecified form of shigillosis.

Back to list Previous article Next article

Complications

In the absence of timely and correct treatment, patients may experience the following consequences:

- development of toxic shock (acute poisoning of the body with inhibition of the functions of vital organs);

- violation of the composition of intestinal microflora (dysbacteriosis);

- intestinal perforation (rupture);

- peritonitis (inflammation of the peritoneum as a result of the release of intestinal contents);

- severe dehydration;

- disruption of the heart.

Less commonly, dysentery causes inflammation of the membranes of the heart and joints. Only timely consultation with a doctor and initiation of treatment will help to avoid such complications.

Is lifelong immunity formed after suffering from dysentery?

Unfortunately no. The immunity of a person who has recovered from the disease is only temporary and lasts 4-12 months. After this, the possibility of re-infection cannot be ruled out.

The main way to prevent intestinal infections is frequent hand washing, washing fruits and vegetables, and preference for heat-treated food.

The good news is that with improved hygiene standards (especially in 2022 due to the COVID-19 epidemic) and literacy in antibiotic prescribing, the incidence of dysentery is on the decline. Vaccines against some of its pathogens are also being developed. And perhaps in the future humanity will be able to get rid of this dangerous disease. MAKE AN APPOINTMENT PRICES

Causes of dysentery in adults

Infection caused by Shigella bacteria is transmitted in several ways:

Household - when caring for a sick person and through common household items.

Food - consuming products or using utensils that have been exposed to the dysentery pathogen. During the warm season (especially summer and autumn), food products become contaminated by flies that carry fecal particles containing bacteria. If hygienic standards are not observed in public catering, and food and utensils undergo insufficient heat treatment, then this is fraught with an outbreak of group dysentery.

Infection can occur by drinking water from open bodies of water or swimming in them. In some cases, tap or well water may be contaminated.