Type of infection and route of infection

The causative agent of the disease is intestinal bacteria Enterobacteriaceae from the genus Yersinia. They are gram-negative rods up to 0.9 microns in size, growing on regular and depleted nutrient media. The most favorable temperature for them is in the range from +4 to +8 degrees, at which they are able to survive for a long time and actively reproduce on various foods. The mechanism of transmission of yersioniasis infection is close to pseudotuberculosis.

Some strains of bacteria are resistant to pasteurization, but boiling kills any of them within a few seconds. They are also sensitive to the effects of disinfectants. The peak incidence is usually observed in November and spring. People of any age are susceptible to the disease; yersiniosis is often found in children. Women are more resistant to pathogens than men.

Pathogens enter the human body through the fecal-oral or alimentary route, through a transfusion of contaminated blood, or directly under the skin through injury or injection. Transmission of intestinal yersiniosis infection can occur through contaminated foods that have not undergone heat treatment - meat, vegetables and milk, as well as water from open sources.

Classification

The classifying signs of yersiniosis are clinical manifestations, severity and course of the disease. A detailed classification of yersiniosis is presented in the table.

| Classification sign | Form of yersiniosis | Explanations |

| Clinical manifestations | gastrointestinal | occurs with symptoms of gastroenteritis (inflammatory disease of the stomach and intestines), ileitis (inflammation of the large intestine) and appendicitis |

| generalized | may occur as sepsis (a general infection of the body) with symptoms of hepatitis (inflammation of the liver), meningitis (inflammation of the brain), pneumonia (inflammation of the lungs) or pyelonephritis (inflammatory kidney disease) | |

| secondary focal | characterized by disorders of various organs and systems, joints (arthritis), heart (myocarditis), intestines (enterocolitis) and other organs are often affected | |

| Heaviness | light | the severity of the disease depends on the prevalence of infection, the age of the patient and the state of immunity |

| moderate severity | ||

| heavy | ||

| Flow | acute | usually recovery occurs 2-3 weeks after the first symptoms appear |

| chronic | clinical manifestations of the disease do not subside for several months | |

| recurrent | characterized by alternating periods of exacerbation and improvement of the patient’s condition |

Causes of infection

The disease develops when the bacterium Yersinia enterocolitica enters the body. Yersinia is well preserved in low temperatures, in water and soil, but is sensitive to ultraviolet rays, drying, boiling and disinfectant solutions.

Wild and domestic animals become the reservoir and source of yersiniosis: rodents, livestock (mainly pigs), dogs. Sick people can spread the infection, but person-to-person transmission is rare. The disease is transmitted through food and water by consuming contaminated food and water. If hygiene rules are violated, in rare cases, contact-household transmission is possible.

Transmission routes and epidemiology

The causative agent of the disease lives in the soil. It enters the animal’s body along with water and food. A key role in the transmission of infection is played by pets (cats and dogs), as well as farm animals and rodents. Rats and mice run around warehouses and cellars and their feces can end up on food and water tanks.

You can become infected through contact-household and fecal-oral routes.

The main route of infection is through consumption of contaminated water or animal products, particularly vegetables and dairy products. Workers in food processing units, as well as poultry and livestock farms are at risk.

In addition, experts do not exclude the contact method of transmission of yersiniosis infection. If hygiene standards are not followed, you can become infected, for example, through shared utensils. Outbreaks of the disease were observed in educational institutions and other organized groups.

Attention! Children from three to six years old are four times more likely to get sick.

During its life, the microbe releases toxic substances that affect the internal organs of a person. The bacterium enters the human body through the oral cavity. It then enters the stomach through the esophagus and then the small intestine.

It is here that active reproduction of pathogenic microflora occurs, which provokes the development of enteritis. Some harmful microorganisms may remain in the stomach and cause an inflammatory reaction there. This causes the development of gastroenteritis. The spread of infectious agents into the lower intestines causes colitis, enterocolitis and appendicitis.

No ads 1

Pathogenesis

The pathogen enters the body through the mouth, then the bacteria penetrate through the digestive tract into the mucous membrane of the small intestine, where an inflammatory process develops. If the pathogen penetrates nearby lymph nodes, the patient develops mesenteric lymphadenitis (inflammation of the lymph nodes of the abdominal cavity). The pathological process can stop here. But if bacteria overcome the lymphatic barrier and enter the blood, the infection spreads throughout the body and affects other organs: joints, liver, kidneys, spleen.

Symptoms of yersiniosis

The incubation period for yersiniosis is 1-6 days. The disease begins with a rise in body temperature to 39-40 ºC, chills, headaches and muscle pain; in severe cases, disorders of the nervous system are added - dizziness, anxiety, insomnia. Subsequently, the clinical picture depends on the form of yersiniosis.

- Gastrointestinal yersiniosis is accompanied by dyspeptic disorders: nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and possibly moderate enlargement of the lymph nodes.

- Generalized yersiniosis is characterized by a variety of symptoms, an increase in temperature to critical values - over 40 ºC, accompanied by severe joint pain, inflammation in the respiratory system (cough, runny nose, sore throat). There is a high probability of a macular nodular rash appearing on the palms and soles, less often on other parts of the body. Approximately 50% of patients develop abdominal pain and indigestion.

- Secondary focal yersiniosis usually develops 2-3 weeks after the onset of the disease. Clinical manifestations depend on which organs the infection affects. More often it occurs as polyarthritis (inflammation of the joints) or enterocolitis (inflammatory bowel disease), in most cases it has a protracted and chronic course.

In 10-20% of patients, yersiniosis occurs in the form of erythema nodosum. Large painful nodules form under the skin of the legs, thighs and buttocks. Their number varies from a few pieces to two or more dozen. After 2-3 weeks, the nodules resolve on their own.

The duration of the disease depends on the form of yersiniosis and ranges from 2-3 days to several months. Gastrointestinal yersiniosis has the easiest course, the most severe course is in the generalized form.

Yersiniosis: expanding traditional ideas about diagnosis, treatment and medical examination of patients

Yersiniosis is widespread in the Russian Federation, and the consistently low level of officially registered incidence does not reflect the true state of the problem. Yersiniosis has now gone beyond the scope of a purely infectious pathology, becoming a therapeutic problem due to the “weak” laboratory base used in practical healthcare, problems in choosing treatment tactics and rehabilitation of patients. Clinicians are particularly concerned about the adverse consequences of yersiniosis, in particular, the chronicity of the infectious process and the formation of systemic autoimmune diseases as a result of the disease [1].

Although in recent years the clinical manifestations of the disease, including the chronic course, have been described in sufficient detail, and significant adjustments have been made to the understanding of the links of immunopathogenesis, practicing doctors know how difficult it is to make a diagnosis, and most importantly, to select treatment for patients that is adequate to the stage of the disease.

As our experience shows, patients with yersiniosis, due to the polymorphism of clinical manifestations of different periods of the disease, are often referred not to an infectious disease specialist, but to doctors of other specialties (gastroenterologists, rheumatologists, endocrinologists, hematologists, etc.), each of whom makes a diagnosis, in fact, being syndromic, and, as a result, prescribes only symptomatic treatment. This statement is based on data from long-term monitoring of yersiniosis survivors, according to which recurrent course among hospitalized patients is recorded extremely rarely (1.3%) and does not correspond to real data on the true frequency of relapses (from 15.8% to 44% in different years).

Apparently, such a rare hospitalization of these patients is associated with the lack of long-term outpatient follow-up of patients who have had yersiniosis, as a result of which, after discharge from the hospital, they fall out of the field of view of the infectious disease specialist, and developing relapses are mistakenly interpreted by other specialists. However, it is early diagnosis and timely treatment that is given the leading role in the prevention of post-yersinia immunopathological diseases, leading to a long-term decrease in performance and disability of patients.

Diagnostic drugs and test systems widely used in practical medicine have rather low sensitivity and efficiency [2, 3]. Long-term monitoring of the diagnosis of “yersiniosis” in patients hospitalized at ICH No. 2 in Moscow has shown that over the past ten years the number of erroneous diagnoses of “yersiniosis” has been steadily increasing, which leads to unnecessary antibiotic therapy and long-term disability of patients. Thus, at the prehospital stage, 57.6% (ranges from 50.9% to 66.3% in different years) of patients are mistakenly diagnosed with yersiniosis, and the patients do not receive adequate treatment in specialized departments of general clinical hospitals.

In the infectious diseases hospital, 42% of these patients had other infectious diseases as their final diagnosis (acute intestinal infections, ARVI, enteroviral diseases, infectious mononucleosis, hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome, viral hepatitis, generalized chlamydia, leptospirosis, HIV, brucellosis, tularemia, etc. .) and 58% had non-infectious pathology. Of particular concern is yersiniosis, which is misdiagnosed at the prehospital stage in 5.7–15.2% of patients with acute surgical pathology requiring emergency surgical intervention [4, 5].

One cannot but agree with the opinion of V. A. Orlov et al. (1991) that “most diagnostic errors are due to an incorrect approach to the diagnostic process.” Apparently, only this can explain the fact that over the course of ten years, 2.9–9.1% of patients with suspected yersiniosis are eventually diagnosed with heart and vascular diseases, and 2.8–6.4% with intestinal tumors , lungs and pelvic organs, in 2.9–7.1% - Hodgkin lymphoma, lympho- and myeloid leukemia, in 2.8–6.1% - diseases of the endocrine system (toxic goiter, thyrotoxicosis, autoimmune thyroiditis), in 2 1–12.1% - inflammatory diseases of the genital organs.

In our opinion, one of the main reasons for diagnostic errors leading to both under- and overdiagnosis of yersiniosis is the low information content of insufficiently specific techniques and diagnostic tools, as well as non-compliance with existing recommendations for the diagnosis of yersiniosis. In the Russian Federation there are modern diagnostic drugs, methods and culture media for the indication and identification of Yersinia enterocolitica and antibodies to them, but the system of their use is not unified, and the assessment of specificity is imperfect.

Laboratory diagnosis of yersiniosis should include bacteriological, immunodiagnostic and serological methods. The main method is bacteriological - seeding the patient’s biological material (feces, urine, washings from the back of the throat, blood clot, sputum, bile, cerebrospinal fluid, surgical material, etc.), material from the external environment and from animals on nutrient media to detect Y growth enterocolitica followed by culture identification. At least four materials must be tested (for example, feces, urine, blood, pharyngeal wash). The optimal time for collecting material is the first 7–10 days of illness. It is extremely rare to obtain a culture of Y. enterocolitica from material from patients with prolonged course and secondary focal forms of yersiniosis.

The main disadvantages of the bacteriological method are the low frequency of obtaining culture growth - on average in the Russian Federation, Y. enterocolitica is isolated in 2-3% of samples, 0.81%, and retrospectiveness (the final result is on the 21-28th day of production) [2]. For more than ten years, in the bacteriological laboratory of the IKB No. 2 in Moscow, it was possible to isolate Y. enterocolitica in only 0.2% of the samples taken (only in the generalized form of yersiniosis), which is consistent with the data of the GSEN center in Moscow and is four times worse, than in the Russian Federation as a whole [2, 3].

Immunodiagnostic methods make it possible to detect Y. enterocolitica antigens in clinical material up to the 10th day from the onset of the disease (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), coagglutination reaction (ICA), immunofluorescence reaction (RIF), indirect immunofluorescence reaction (IRIF), agglutination and lysis reaction ( RAL)). According to manufacturers, the sensitivity of test systems reaches 104–105 m cells/ml, and the efficiency of testing coprofiltrate and serum in the first five days of illness is 83–85%. Promising methods are methods for indicating and identifying pathogenic Y. enterocolitica by a set of phenotypic characteristics associated with its pathogenicity determinants (API test systems (sensitivity 79%) and genetic methods for diagnosing and typing Yersinia (polymerase chain reaction (PCR), multiprimer PCR) .The advantages of PCR include the speed of analysis (up to 6 hours), information content, high sensitivity and specificity. However, in practical medicine, the specificity of this reaction turned out to be the most vulnerable. The immunoblotting method, which makes it possible to detect and identify proteins (antigens) of Yersinia using antisera, in RF is used unreasonably rarely.

To determine specific antibodies to Y. enterocolitica antigens, serological methods are used. The study must be carried out from the 2nd week of illness in paired sera with an interval of 10–14 days. A 2–4-fold dynamics of antibody titer in paired sera is desirable, which, however, is not always observed in practice. At the onset of the disease, the most informative reaction is ELISA with determination of IgA, IgM and IgG, ELISA; at 3–4 weeks - ELISA, ELISA, agglutination test (RA), RSC, A-BNM. For the qualitative determination of IgA and IgG class antibodies to the virulence factors of pathogenic strains of Y. enterocolitica, you can use the immunoblotting method, which is used for the differential and retrospective diagnosis of yersiniosis. In the chronic course of yersiniosis, ELISA with the determination of IgA and IgG and immunoblotting are informative.

Despite the large number of test systems offered and various companies guaranteeing a high frequency of detection of yersinia antigens or antibodies to them (up to 85%), in practical health care the indirect hemagglutination test (IRHA) and RA are more often used, which actually makes it possible to diagnose yersiniosis only in every fourth patient (25.3%): with the abdominal form - in 41.7% of patients, with the generalized form - in 21.1% of patients, with the secondary focal form - in 30.8% of patients. It is extremely rare that serological methods confirm the gastrointestinal form of yersiniosis (4.5%). There is no reliable relationship between the level of antibodies to Yersinia and the severity of yersiniosis.

Quite often (21.1% of cases), attending physicians interpret a single detection of specific antibodies to Y. enterocolitica in the blood of patients as laboratory confirmation of yersiniosis. However, in the majority of patients (54.1%), the titer does not exceed 1:200, which means it cannot be considered laboratory confirmation of the clinical diagnosis. The explanation for this lies in the intensive circulation of Yersinia in the environment and among the population. According to materials from the GSEN centers in the Russian Federation, when examining healthy individuals, specific antibodies to Y. enterocolitica are detected in 0.4–4.4% of samples [2]. However, the immune layer among the population is much higher - 18.2–19.6% [6, 7].

Antibody titers to Y. enterocolitica in the direct hemagglutination reaction (DHR) and RA above 1:200 are recorded only in 45.9% of patients. However, a one-time blood test using the mentioned methods, even with a high titer, cannot be unambiguously interpreted as yersiniosis. Thus, in our practice there was a patient with severe articular syndrome, during a dynamic blood test of which antibodies to Y. enterocolitica using the RA method were at a constant level of 1:102,400, which only indicated that she had suffered yersiniosis and was not an indication for prescribing antibacterial therapy.

Analyzing the general recommendations for laboratory diagnosis of yersiniosis and the current situation in practice, we can state that laboratory diagnosis of the disease remains at the level of the early 90s. The reasons lie not only in the use of insufficiently effective methods, but also in non-compliance with existing recommendations for diagnosing yersiniosis. Thus, in most cases, when making a diagnosis, practitioners rely on a single examination of material taken from the patient and the titer of antibodies to Y. enterocolitica. However, the serological criterion for the diagnosis of “yersiniosis” should be considered not so much the achievement of the “diagnostic” titer of specific antibodies, but rather its dynamics when studying paired sera with an interval of 10–14 days. To increase the efficiency of diagnosing yersiniosis, we recommend examining the blood serum of patients with yersiniosis using at least three methods (for example, RNGA, RSK and ELISA, etc.).

Pathogenesis of yersiniosis. The choice of management tactics and drug treatment for patients with yersiniosis directly depends on the pathogenesis of different stages of the disease. It is known that the nature of the interaction of Y. enterocolitica with the macroorganism depends on the set of pathogenicity factors of the strain, the dose of the infection, the route of administration and the immunological reactivity of the macroorganism. Taking into account the available experimental data, the pathogenesis of yersiniosis in humans can be presented as follows. Y. enterocolitica enters the human body orally, and the disease develops after a fairly short incubation period - from 15 hours to 6 days (on average 2-3 days). The bulk of Yersinia overcomes the protective barrier of the stomach. In the stomach and duodenum, catarrhal-erosive, less commonly, catarrhal-ulcerative gastroduodenitis develops. Then the development of the pathological process can go in two directions: either local inflammatory changes will occur in the intestine, or a generalized process will develop with lympho- and hematogenous dissemination of Y. enterocolitica.

If the disease is caused by serotypes of Y. enterocolitica, which have pronounced enterotoxigenicity and low invasiveness, then, as a rule, processes localized in the intestine develop, the manifestations of which will be damage to the gastrointestinal tract (catarrhal-desquamative, catarrhal-ulcerative enteritis and enterocolitis) and intoxication.

If Y. enterocolitica penetrates the mesenteric nodes, the abdominal form develops. The pathomorphology of yersinia lymphadenitis is a combination of infectious, inflammatory and immunological processes. In the appendix, the inflammatory process is often catarrhal in nature, but the development of a phlegmonous process with subsequent destruction of the appendix and the development of peritonitis is possible. Gastrointestinal and abdominal forms of yersiniosis can be either independent or one of the phases of the generalized form.

There are two known ways of generalization of the yersinia process - invasive and non-invasive. The invasive route of entry of Y. enterocolitica through the intestinal epithelium is the classic and best studied. If the infection is caused by a highly virulent strain of Y. enterocolitica, then a non-invasive route of penetration through the intestinal mucosa inside the phagocyte is possible.

During the period of convalescence, the body should be freed from yersinia and the impaired functions of organs and systems should be restored, resulting in clinical and laboratory recovery. However, such a favorable development of events is possible only with an adequate immune response and the absence of immunogenetic and epigenetic markers of an unfavorable outcome. Dispensary observation of convalescents for five years after acute yersiniosis showed that the outcomes of yersiniosis can be:

1) clinical and laboratory recovery (55.2%);

2) unfavorable outcomes (29.2%):

a) with the formation of a chronic course (57%);

b) with the formation of pathological conditions and diseases of an autoimmune nature (43%);

3) relatively unfavorable outcomes with a predominance of the infectious and inflammatory component (10.5%):

a) with exacerbation of chronic inflammatory diseases (35.5%);

b) with the formation of new diseases with a predominance of the infectious-inflammatory component (64.5%);

4) residual effects (short-term low-grade fever, periodic myalgia and arthralgia, neurological symptoms involving nerve plexuses and roots, autonomic reactions, asthenic and hypochondriacal syndromes, the phenomenon of interoception, etc.) (5.1%).

The best prognosis is for patients aged 19–25 years. Among them, 71% recover. At the same time, 45% of survivors aged 26–45 years develop pathological conditions of various origins that are included in the category of unfavorable outcomes of yersiniosis.

According to our data, doctors diagnose secondary focal forms of yersiniosis more often than they actually form. This is due to the absence of pathognomonic clinical manifestations of secondary focal forms of yersiniosis and their systemic nature. The group of patients with the so-called secondary focal form of yersiniosis is not homogeneous. This group often unreasonably includes both patients with a pathological process of yersiniosis etiology (for example, the chronic course of yersiniosis), and patients with a chronic course of post-yersiniosis infection, with emerging new acute processes of non-yersinia etiology and patients with autoimmune pathology. This state of affairs requires special attention and analysis of clinical and laboratory parameters from the practicing physician, since further treatment tactics, and therefore the outcome of the entire pathological process, depend on their understanding.

In patients with chronic yersiniosis, Y. enterocolitica continues to circulate in the body for a long time. According to our data, the chronic course of yersiniosis develops in 16.6% of patients and is more often observed in people over 25 years of age. The “shelter” of pathogens is the lymph nodes, small intestine and cells of the macrophage-monocyte series. Activation of foci of infection can clinically manifest itself in the form of urethritis, nephritis, enteritis, meningitis, etc. From the foci, Yersinia antigens enter the blood as part of immune complexes, causing reactive arthritis, damage to the kidneys, intestines, organs of vision, etc. Slowing the speed of blood flow in the tissues - targets creates favorable conditions for the deposition of Y. enterocolitica antigens. A criterion for the persistence of the pathogen can be considered long-term (more than 6 months) circulation of specific IgA to Yersinia lipopolysaccharide.

Among the diseases that are of an autoimmune nature and are the outcome of yersiniosis, seronegative spondyloarthropathy (usually reactive arthritis and Reiter's syndrome), rheumatoid arthritis, autoimmune thyroiditis and Crohn's disease predominate.

Treatment of patients with yersiniosis and pseudotuberculosis should be comprehensive, pathogenetically substantiated and carried out taking into account the clinical form and severity of the disease (

), (

). The most important task is to relieve symptoms of the acute period and prevent adverse outcomes of the disease. Hospitalization of patients with yersiniosis is carried out according to clinical and epidemiological indications. For mild and uncomplicated moderate cases, treatment at home is allowed. According to epidemiological indications, patients belonging to the decreed group (military personnel, workers of water utilities, catering departments, etc.) are hospitalized.

For dietary nutrition, tables No. 4, 2 and 13 are used. Antibacterial therapy is prescribed for 10–14 days (for the gastrointestinal form it can be limited to seven days) to all patients, regardless of the form of the disease, as early as possible (preferably before the third day of illness) [8] .

The choice of drug depends on the antibiotic sensitivity of Yersinia strains circulating in a given area (determined twice a year). Currently, preference is given to fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins [9, 10].

The main direction of pathogenetic therapy for the gastrointestinal form of yersinia infection is oral (parenteral) rehydration and detoxification with polyionic solutions.

The treatment tactics for patients with the abdominal form are agreed with the surgeon. The surgeon decides whether surgical intervention is necessary. Before and after surgery, etiotropic and pathogenetic treatment is carried out in full.

In the generalized form, etiotropic drugs, in most cases, are prescribed parenterally. In generalized forms with symptoms of pyelonephritis, pefloxacin has proven itself well - 0.8 g/day. Levomycetin succinate is used for the development of meningitis of yersinia etiology (7–100 mg/kg per day). In severe cases of the generalized form, several courses of parenteral antibiotic therapy are carried out. Start with gentamicin - for 2-3 days at 2.4-3.2 mg/kg per day, then 0.8-1.2 mg/kg per day. In the absence of a therapeutic effect or drug intolerance, streptomycin sulfate is used at a dose of 1 g/day. If hepatitis develops, you should avoid prescribing medications that have a hepatotropic effect. For patients with a septic form of the disease, it is advisable to administer two or three antibiotics of different groups (fluoroquinolones, aminoglycosides, cephalosporins) intravenously. If antibacterial therapy is ineffective, L. A. Galkina, L. V. Feklisova (2000) recommend using polyvalent yersinia bacteriophage (50.0–60.0 ml 3 times a day, No. 5–7) as monoetiotherapy or in combination with antibiotics [eleven].

In addition to etiotropic treatment, pathogenetic therapy is indicated (detoxification, restorative, desensitizing drugs, stimulants). In complex therapy, agents for the treatment of dysbiotic disorders must be used.

Most patients with severe asthenic, vegetative and neurotic manifestations require taking nootropic drugs, tranquilizers, bromides, peony infusion, motherwort tincture, valerian root decoction, etc. The selection of therapy in such cases is coordinated with a neuropsychiatrist and a vegetarian.

Treatment of patients with a secondary focal form of yersiniosis is carried out according to an individual scheme for each patient. Antibacterial drugs have no independent significance, but should be prescribed when clinical and laboratory signs of intensification of the infectious process appear and there is no history of taking antibiotics. Treatment of patients is coordinated with a rheumatologist, gastroenterologist, endocrinologist, psychoneurologist and other specialists (as indicated). Immunocorrectors should be prescribed to patients strictly according to indications in the absence of laboratory signs of an autoimmune process based on the results of a study of the immune status and autoantibodies in the patient’s blood.

Dispensary observation of convalescents. There is still no consensus on the duration and tactics of dispensary observation of convalescents of yersiniosis and pseudotuberculosis. In accordance with the orders and guidelines of the Ministry of Health (Order No. 408 of 1989; Appendix 6 to the Order of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation of September 17, 1993 No. 220 “Regulations on the office (department) of infectious diseases”, etc.), monitoring of convalescents of yersinia infection is carried out in depending on the nosology and severity of the disease for 1–6 months after discharge from the hospital (for mild forms - one month, for moderate forms - three months, for severe forms - six months).

Some researchers recommend using the following indicators to predict unfavorable outcomes of yersiniosis: unfavorable premorbid background (chronic diseases, grade 3-4 dysbiosis, burdened allergic history, etc.), long-lasting decrease in albumin, alpha proteins, urea-ammonia ratio, dysproteinemia, increased concentration blood ammonia, fibrinogen, neutrophilia, monocytosis, lymphocytosis, eosinophilia, low activity of the complement system, decreased levels of T- and B-lymphocytes in the period of convalescence and nonspecific resistance factors, high levels of circulating immune complexes (CIC), the presence of HLA B7, B18 and B27 , O (I) blood group.

However, dynamic observation of patients who have had yersiniosis and the use of modern methods of statistical processing of clinical and laboratory parameters allow us to express the opinion that the clinical manifestations of yersiniosis and pseudotuberculosis, their severity and duration are not objective criteria for prognosis, and therefore cannot be used for prognosis course and outcome of the disease. The immunoprognostic testing algorithm we created (

) patients in the acute period of the disease and the developed set of criteria for assessing immunograms for yersiniosis enable doctors to predict an unfavorable course and outcome already in the first 2–4 weeks from the onset of the disease [12, 13].

In our opinion, if the patient does not have criteria for adverse outcomes of yersiniosis infection, dispensary observation of convalescents is recommended for one year after discharge from the hospital. If there are indicators of possible adverse outcomes of yersiniosis, dispensary observation should be carried out for five years after discharge from the hospital - the first year every 2-3 months, then once every six months in the absence of complaints and deviations in health. In the presence of clinical and laboratory problems - more often, as necessary. According to indications, patients should undergo clinical, laboratory and instrumental examination by a rheumatologist, endocrinologist, cardiologist, ophthalmologist, dermatologist, etc.

The tactics of medical examination of patients with yersiniosis are not regulated at all by orders of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Based on our own results of long-term observation of patients with yersiniosis, we recommend the following tactics for their clinical examination. After discharge from the hospital, the duration of clinical observation for survivors of yersiniosis and pseudotuberculosis in the absence of genetic and immunological prognostic criteria for adverse outcomes should be one year, and if they are present, at least three years. To monitor the completeness of recovery, it is recommended to use the following scheme: during the first year after the acute period, patients must be examined comprehensively (clinical, laboratory, immunological methods) every 2–3 months, then once every six months in the absence of complaints and deviations in health. In the presence of clinical and laboratory problems - more often, as necessary. According to indications, during clinical examination, patients should be consulted with other specialists (rheumatologist, gastroenterologist, endocrinologist, cardiologist, ophthalmologist, dermatologist, gynecologist and gynecologist-endocrinologist) with the necessary laboratory and instrumental studies.

Literature

- Shestakova I.V., Yushchuk N.D., Andreev I.V., Shepeleva G.K., Popova T.I. On the issue of the formation of immunopathology in patients with yersiniosis // Ter. archive. 2005; 11:7–10.

- Opochinsky E. F., Mokhov Yu. V., Lukina Z. A., Yasinsky A. A. Analysis of the activities of the centers of the State Sanitary and Epidemiological Supervision of the Russian Federation for laboratory diagnosis of yersiniosis. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 42–43.

- Filatov N. N., Salova N. Ya., Golovanova V. P., Shesteperova T. I. Current state of laboratory diagnosis of yersiniosis in Moscow. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 59–60.

- Shestakova I.V., Yushchuk N.D., Popova T.I. Yersiniosis: diagnostic errors // Doctor. 2007; No. 7: 71–74.

- Yushchuk N.D., Shestakova I.V. Problems of laboratory diagnosis of yersiniosis and ways to solve them // ZhMEI. 2007; No. 3: 61–66.

- Ghukasyan G. B., Khachatryan T. S., Aleksanyan Yu. T., Khanjyan G. Zh. Epidemiological patterns of yersiniosis in Armenia. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 13.

- Belaya Yu. A. Yersinia in “healthy” people. Results of long-term prospective studies. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 5.

- Karetkina G. N. Yersiniosis. In the book: Yushchuk N. D., Vengerov Yu. Ya. (ed.) Lectures on infectious diseases. M.: VUNMC; 1999: 339–354.

- Luchshev V.I., Andreevskaya S.G., Mikhailova L.M. et al. Treatment of patients with yersiniosis with fluoroquinolone drugs // Epidem. and infectious Diseases. 1997; 3:41–44.

- Dmitrovsky A. M., Karabekov A. Zh., Merker V. A. et al. Clinical aspects of yersiniosis in Almaty. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 17–18.

- Galkina L. A., Feklisova L. V. Results of the use of polyvalent yersiniosis bacteriophage in the treatment of yersiniosis in children. In the book: Infections caused by Yersinia (yersiniosis, pseudotuberculosis), and other current infections. St. Petersburg, 2000: 11.

- Shestakova I.V., Yushchuk N.D., Balmasova I.P. Clinical and prognostic criteria for various forms and variants of the course of yersinia infection // Ter. archive. 2009, vol. 81,11: 24–32.

- Shestakova I.V., Yushchuk N.D. Chronic yersiniosis as a therapeutic problem // Ter. archive. 2010, vol. 82, 3: 71–77.

I. V. Shestakova , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor N. D. Yushchuk , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor, Academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences MGMSU , Moscow

Contact information for authors for correspondence

Diagnostics

To diagnose yersiniosis, laboratory and instrumental research methods are used. If the disease is suspected, the following are prescribed:

- Bacteriological examinations of sputum, blood, feces, and urine help to isolate the pathogen, but diagnosis requires considerable time, sometimes taking up to 30 days to obtain results;

- enzyme immunoassay and agglutination reaction are used as express diagnostics, helping to detect antibodies to the pathogen in the blood;

- hardware research methods (electrocardiogram, ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging) are carried out to assess the condition of internal organs.

Note! In some cases, yersiniosis occurs with mild symptoms or is disguised as other infections. Therefore, when the first signs of the disease appear, it is necessary to consult a doctor to determine the cause of the deterioration in well-being.

Pseudotuberculosis and yersiniosis

Pseudotuberculosis, or extraintestinal yersiniosis, is a disease caused by Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. The incubation period can last up to three weeks. This infectious disease can affect the digestive tract, musculoskeletal system and skin.

Attention! Pseudotuberculosis has nothing to do with Koch's bacillus, which causes tuberculosis. It simply causes similar morphological changes in parenchymal organs.

Pseudotuberculosis and yersiniosis are caused by microorganisms of the same variety. The clinical picture of these pathologies is very similar. In the first case, it all begins with the appearance of symptoms of general intoxication, severe headaches, redness and swelling of the throat, pain in the joints and muscles. The tongue becomes dirty gray in color.

After two to four weeks, red dots begin to appear on the body. The rash usually goes away after one week, leaving behind a scaly flaking. The main symptom of the disease is the appearance of a rash on the arms and legs. The skin in these places peels off so much that it comes off in whole layers.

Pseudotuberculosis got its name due to the fact that lesions were found in the lymph nodes and internal organs that looked like capsules with curdled contents. In this case, epithelial cells are absent. Pseudotuberculosis can be treated with antibiotics, hormonal agents, and drugs that eliminate intoxication.

Nutrition for intestinal infections in adults

You can become infected with pseudotuberculosis through the fecal-oral route through the following foods:

- unwashed vegetables and fruits;

- insufficient heat treatment of dairy, meat and fish products;

- confectionery and bakery products that were stored in dirty containers;

- dried fruits;

- water, juices.

Differential diagnostics, that is, comparative analysis, can be carried out by a specialist based on research results. A bacteriological analysis of stool and blood is carried out. Pathogen DNA can be detected using PCR diagnostics. Immunological and serological analysis will help identify antibodies to the pathogen.

A characteristic symptom of pseudotuberculosis is a rash on the hands

Treatment of yersiniosis

Patients with yersiniosis are hospitalized in the infectious diseases department of the hospital. The main drugs in the treatment of yersiniosis are antibiotics and antimicrobials. The course of treatment depends on the severity of the disease, usually 10-14 days. As additional support measures, intravenous infusions of water-salt solutions with vitamins, anti-allergic and anti-inflammatory drugs are prescribed, and in severe cases - hormonal drugs. To normalize digestion, enzymes, probiotics and prebiotics, and vitamin and mineral complexes are used.

Laboratory diagnostics

A general practitioner or emergency physician may suspect yersiniosis, but the final “verdict” is made by an infectious disease specialist. To do this, he will need data from clinical, laboratory and instrumental studies. To make a diagnosis, a bacteriological examination is first performed. Biological material that is taken from a person is sown on special nutrient media.

The biomaterial can be urine, feces, sputum, or throat culture. In parallel with this, other tests are prescribed, since the diagnosis itself takes about two weeks. In addition, a serological method is used to detect antibodies in the blood. A passive hemagglutination reaction (RPHA) is performed. The patient's blood is also taken for analysis, which is interpreted by a qualified specialist.

With yersiniosis, the following changes in hematological parameters may be detected: anemia, increased ESR, leukocytosis, an increase in the number of eosinophils, while the number of lymphocytes decreases. Microbiological diagnostics will help make an accurate diagnosis. Learn more about diagnosing yersiniosis in this article.

Complications

Due to the diversity of clinical manifestations, yersiniosis can be complicated by various diseases. Patients often develop the following pathologies:

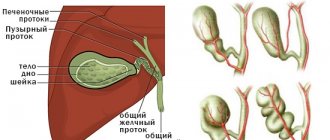

- myocarditis is an inflammatory disease of the heart muscle;

- hepatitis and cholecystitis - inflammation of the liver and gall bladder;

- pancreatitis - damage to the pancreas;

- intestinal obstruction;

- appendicitis;

- peritonitis - inflammation of the lining of the abdominal cavity;

- meningoencephalitis - inflammation of the substance and membranes of the brain;

- arthritis – inflammation of the joints.

Note! Late administration of antibacterial drugs (after three days from the onset of the first symptoms) does not guarantee the prevention of complications and the infection becoming chronic.

Consequences

Of particular danger is the development of autoimmune processes and inflammation of internal organs. The difficulty is in treating appendicitis with yersiniosis. The development of meningitis and osteomyelitis is also dangerous. In general, the prognosis is favorable. In most cases, the disease has a benign course.

Death from yersiniosis is quite rare. The most unfavorable complication is blood poisoning. The abdominal form can cause phlegmonous appendicitis and even peritonitis. Yersiniosis can lead to life-threatening complications.

In some cases, the infectious process causes death. Many complications of this disease require surgical intervention. In order to prevent the development of unpleasant consequences, it is necessary to consult a doctor promptly when the first symptoms appear.

Prevention

Specific prevention of yersiniosis has not been developed. Preventive measures are of a general nature and consist of observing the rules of personal hygiene, sanitary and epidemiological control of medical institutions, catering establishments and the food industry. An important measure is also to maintain reservoirs in proper condition and introduce bans on swimming in places with a high risk of infection. To control the spread of infection, deratization (destruction of rodents) is carried out in populated areas and agricultural lands.

Clinical guidelines

Preventive measures are important to preserve human life. A healthy lifestyle will help prevent the occurrence of many pathologies, including yersiniosis. Parents should explain to their child the importance of maintaining good personal hygiene. Otherwise, ideal conditions may be created for the activation of pathogenic microflora in the intestines. It is important to monitor not only the storage of food, but also the quality of preparation, especially for products of animal origin.

Attention! Food department workers use last year’s vegetables only after heat treatment, in accordance with the requirements of the Sanpin.

To prepare salads, you must use only good-quality vegetables from this year. Preventive measures must be observed not only in everyday life, but also in children's, medical and food institutions. Monitoring the condition of water sources is mandatory. Rodent control must also be carried out.

Vegetables must be stored in specially equipped rooms. This will avoid the contamination of rodent feces, which are the main carriers of yersiniosis pathogens. Moreover, such premises must be disinfected and well ventilated.

For safety reasons, vegetables should be stored in premises specially equipped for this purpose.