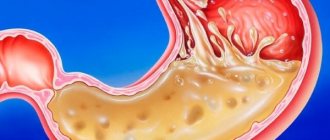

If problems arise in the functioning of the digestive system under the influence of increasing secretion of digestive juice, decreasing resistance of the mucous membrane, ulcerative lesions occur in the stomach and duodenum. The pathology is accompanied by severe pain, and as the disease progresses, serious complications arise.

Causes of stomach ulcers

The underlying cause of the development of peptic ulcers in the stomach, small intestine and duodenum is infection with a special bacterium called Helicobacter Pylori. The microbe is transmitted through close interaction between an infected person and a healthy person. However, for the development of mucosal tissue defects, a combination of a number of other factors is required.

The precursor to a stomach ulcer is gastritis and other gastrointestinal diseases, in which the acidity of gastric juice increases, and the causes of ulcers are:

- Frequent drinking of alcohol

- Physical overexertion

- Stressful situations

- Unbalanced diet

- The predominance of spicy, salty foods in food

- Avitaminosis

- Blood clots in the vessels of the stomach

- Injuries in the gastrointestinal tract.

Treatment of stomach ulcers is prescribed after reliable identification of the totality of the causes of the disease. According to the factors causing ulcers, there are:

- Stress ulcers are precursors to injuries, surgeries, liver and kidney failure, and burns.

- Medicinal - caused by ulcerogenic drugs, which include many anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Endocrine - are the result of disturbances in the functioning of the endocrine glands.

Chronic gastric ulcer is often the result of the onset and long development of diabetes mellitus, pancreatitis, and cirrhosis of the liver.

Reasons for development

The main difference between stomach ulcers and other diseases is deep tissue damage.

Even after treatment and a rehabilitation period, scars remain on the walls of the stomach. Medicine identifies several factors that contribute to the manifestation of diseases. Quite often the triggers are stress and medication. All people aged 25 to 50 years are at risk, which is due to the rhythm of life, bad habits, poor diet and constant stress. At the same time, the male population suffers more often from stomach ulcers.

What else provokes the development of ulcers:

- The Helicobacter bacterium causes more than half of all cases. Infection occurs from a sick person, through common objects, saliva, from mother to fetus.

- Taking medications - non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, potassium-containing drugs and a number of others.

- Against the background of concomitant diseases. For example, tuberculosis, autoimmune diseases, cancer.

- Genetic predisposition.

- Metabolic disorders and endocrine diseases.

The acute form of “shock ulcers” can be provoked by injuries, kidney failure, tobacco and alcohol abuse.

Symptoms of stomach ulcer

“If you are experiencing similar symptoms, we advise you to make an appointment with your doctor.

You can also make an appointment by phone. The symptoms of the disease are influenced by age, size, location of the ulcer, and the presence of concomitant pathologies. However, practice shows that there are general signs and characteristic symptoms of stomach ulcers:

- Abdominal pain

- Heartburn, nausea, vomiting

- Flatulence, heaviness in the stomach

- Bloody spots in the stool.

Pain from a stomach ulcer worsens especially after eating. Peptic ulcer disease is characterized by decreased appetite, feeling of thirst, and frequent belching.

A complicated form of the pathology - perforated gastric ulcer - is characterized by intense, pronounced pain radiating to the sternum, back or collarbone. Within 4-6 hours, the pain becomes girdling, fever occurs, the mouth becomes dry, and the skin begins to turn pale. At some point, the pain subsides for a while, but then resumes again. The condition is extremely dangerous and may be accompanied by tachycardia.

(Ends. Starts in No. 32 dated 08/12/2021.)

Peptic ulcer disease

Patients with giant gastric ulcers (>3 cm) ( Fig. 2 ) are usually elderly and may have atypical symptoms, including anorexia and weight loss. They often have an aggressive course of disease with a high incidence of bleeding and high mortality compared with minor ulcers.

Rice. 2. A - giant benign ulcer in a 78-year-old patient. B - study with methylene blue + espumizan. B - two giant gastric ulcers with bleeding

Rice. 3. Giant ulcer of the duodenum bulb. Giant duodenal ulcers ( Fig. 3 ) (more than 2 cm) also have a high incidence of complications, including bleeding, penetration and perforation. Upper endoscopy has advantages in diagnosing giant gastric ulcers over x-ray examination. Giant duodenal ulcers may be missed, which, due to their large size, can be mistaken for a duodenal bulb, pseudodiverticulum, or true diverticulum of the duodenal bulb. Endoscopy is also important to exclude malignancy and rare causes of giant ulcers, including Crohn's disease, eosinophilic gastroenteritis, ischemia, and may be required to treat complications associated with giant size. This category of patients requires surveillance endoscopies to document healing, based on the increased incidence of complications associated with this pathology.

Ulcers that do not heal within 8–12 weeks of antisecretory therapy are considered refractory Caused by persistent H. pylori infection, continued use of NSAIDs, gigantic ulcers requiring more time to heal, cancer, drug tolerance or resistance, or a hypersecretory state. Surveillance endoscopies continue until healing is documented or the etiology is determined (H. pylori, NSAIDs, high gastrin, ischemia). Treatment for refractory ulcers includes treatment of the cause and long-term use of standard doses of PPIs.

H. pylori and NSAIDs are the overwhelming causes of PUP in Europe, Asia, Australia, and some populations in the United States.

A number of less common factors are responsible for the remaining cases:

- False-negative methods for diagnosing H. pylori.

- NSAIDs (recognized or unrecognized).

- Other ulcerogenic drugs (other than NSAIDs).

- Complicated duodenal ulcer (bleeding, stenosis, perforation).

- Smoking.

- Isolated colonization of H. pylori duodenum.

- Old age.

- Gastric hypersecretion (Zollinger-Ellison syndrome).

- Diseases of the duodenum (Crohn's disease, neoplasm/lymphoma, infections).

- H. heilmanii infection.

- Concomitant diseases (malignancy, chronic renal failure, liver cirrhosis).

Other drugs other than NSAIDs

A number of drugs cause or aggravate gastrointestinal tract problems and peptic ulcers - and this list is growing. The role of NSAIDs is well known, but they also increase the toxicity of a number of other drugs.

Acetaminophen. In general, the risk was increased only at doses of 2 to 3 g per day or higher. It was also increased with a combination of NSAIDs plus high-dose acetaminophen compared with acetaminophen alone (Rahme E. et al, 2008).

Bisphosphonates. The risk increased significantly with concomitant use of NSAIDs.

Glucocorticoids. Despite controversy over the years, available evidence suggests that glucocorticoids alone are not associated with an increased risk of PUP.

Clopidogrel. The antiplatelet agent clopidogrel is a significant risk factor for GI bleeding, especially in patients with a pre-existing risk of bleeding or when taking low-dose aspirin or NSAIDs.

Sirolimus. Sirolimus has been associated with aggressive peptic ulcer disease in transplant patients (Smith AD et al, 2002).

Chemotherapy. Several forms of chemotherapy have been associated with PUP.

Hormonal or transmitter-induced, including secondary hypersecretory conditions

Zollinger-Ellison syndrome is a rare neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas or duodenum, consisting of a triad: 1) hypersecretion of gastric acid; 2) hypergastrinemia in fasting serum; 3) natural fulminant PYP with diarrhea (Metz DC, Jensen RT, 2008). Some patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome have more severe or complicated PUP symptoms than patients with idiopathic ulceration (eg, 7% have perforation (Waxman I. et al, 1991)).

With the widespread availability of PPIs, many patients are treated empirically, resulting in a reduction in symptoms, but time is lost to be able to make a diagnosis before the development of metastatic disease. Older studies showed that the average time to diagnosis after the onset of symptoms was more than 6 years (Stage JG, Stadil F., 1979). A recent study identified a reduction in the diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome as a possible consequence of early empiric PPI therapy (Corleto VD et al, 2001).

As stated above, the main danger of a late diagnosis of Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, despite the control of hormonal syndrome, is that such patients have a significant risk of tumor progression with the development of metastases and subsequent negative outcome. It has been established that early diagnosis and surgical intervention lead to a positive outcome in 30–40% of patients (Norton JA, Waxman I. et al, 1991). Patients who underwent surgical resection with normalization of biochemical tests had a 90% chance of recovery over 3 years of follow-up (Fishbeyn VA et al, 1993).

Endoscopic findings in patients with Zollinger-Ellison syndrome may include fold hypertrophy due to prolonged stimulation of the acid-producing mucosa by gastrin, gastric carcinoid tumors (type II) in MEN-1 syndrome, and direct visualization of gastrinoma duodenum (Wilcox CM et al, 2011). However, the absence of such signs is common. In addition, gastric carcinoids (type I) also occur in atrophic gastritis, and fold hypertrophy occurs in H. pylori and other infiltrative conditions. Consequently, endoscopic findings are not always helpful in differentiating Zollinger-Ellison syndrome from other causes of peptic ulceration or hypergastrinemia.

Although ulcers associated with gastrinoma may be indistinguishable from conventional peptic ulcers, several features should raise suspicion ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Features associated with PUP in patients with gastrinoma.

Systemic mastocytosis is characterized by mast cell infiltration of many tissues and symptoms of flushing, itching, abdominal pain and diarrhea (Cherner JA et al, 1988; Jensen RT, 2000). Dyspepsia, duodenal ulcers and severe duodenitis occur in 30–50% of cases and may be associated with basal acid hypersecretion, sometimes resembling gastrinoma (Cherner JA et al, 1988).

Carcinoid syndrome. There is an association of carcinoid syndrome with peptic ulcer disease, which is probably due to ectopic histamine production (Wareing TH, Sawyers JL, 1983).

Basophilia in myeloproliferative diseases. Acid hypersecretion, increased risk of peptic ulcers, and elevated serum histamine concentrations are observed in myeloproliferative disorders associated with basophilia, such as basophilic leukemia and chronic myeloid leukemia with severe basophilia (Anderson W. et al, 1988).

Hyperfunction of antral G cells. It seems likely that antral G cell hyperfunction typically reflects an exaggerated response to H. pylori-induced hypergastrinemia, which is part of the spectrum of H. pylori-associated duodenal ulcers.

Other infections

Herpes simplex virus type 1. The possible involvement of herpes simplex virus type 1 in patients with PUD has been noted due to the increased frequency of anti-HSV-1 antibodies (Lohr JM et al, 1990), as well as the discovery of herpes simplex virus-specific DNA and protein type 1, in the mucosa at the edge of ulcers in a small number of patients (Lohr JM et al, 1990; Kemker BP et al, 1992).

Cytomegalovirus. Has been associated with PUD in immunocompromised patients, in whom it may cause shallow gastric and esophageal ulcers.

Rare infections. Several other very rare fungal, parasitic, and mycobacterial infections can also cause gastroduodenal ulcers and are worth considering in H. pylori-negative and NSAID-negative ulcers.

Mechanical reasons

Duodenal obstruction. Unusual causes of ulcers are associated with various abnormalities of the duodenum, including congenital membranes, hypertrophic pyloric stenosis, and annular pancreas. Duodenal ulcers in these conditions may be present in infancy or childhood, but may also occur during adolescence or adulthood.

Vascular causes

Blood flow is critical to mucosal integrity. Although ischemia of the gastroduodenal mucosa is rare due to the rich vascularity, vascular insufficiency associated with the arterial supply is rarely present in peptic ulcer disease that is not associated with H. pylori infection or NSAID use (Patel VK et al, 2005). Some patients complain of typical ulcer pain, while others may report symptoms suggestive of mesenteric angina with pain after eating. Endoscopy can detect multiple ulcers of the stomach or duodenum.

Chronic mesenteric ischemia is “abdominal angina,” characterized by generalized postprandial abdominal pain lasting up to 3 hours, as well as weight loss. Among the causes leading to damage to visceral vessels, the leading place belongs to atherosclerosis (50–80%) and nonspecific aortoarteritis (20–30%) (Loginov A. S., Zvenigorodskaya L. A., 2000).

Abdominal pain occurs 20–30 minutes after eating, lasts up to 2–3 hours and depends not on the composition, but on the volume of food eaten. This leads to a fear of eating (sitophobia) and, as a consequence, to progressive weight loss (Haberer J. et al, 2004).

Radiation therapy

Intestinal ulcers can occur after abdominal radiation therapy in the second part of the duodenum, which is particularly sensitive to radiation damage. Gastroduodenal ulcers also occur after radioembolization, which is used to treat liver tumors, with an incidence of 3% to 5%. Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and anorexia are symptoms of this complication (Naymagon S. et al, 2010).

Inflammatory and infiltrative diseases

Sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis in the gastrointestinal tract most often affects the stomach, almost always associated with pulmonary disease (Fireman Z. et al, 1997; Farman J. et al, 1997). Ulcerations resembling PUS may occur with widening of mucosal folds.

Crohn's disease. Crohn's disease of the stomach and/or duodenum is often detected (Oberhuber G. et al, 1998), but only sometimes has clinical manifestations. Pathology is represented by obstruction, ulcers, fistulas or bleeding (Yamamoto T. et al, 1999).

Other gastroenteritis. Peptic ulcers, including perforated ones, can occur in association with eosinophilic gastroenteritis (Siaw EK et al, 2005).

Other idiopathic causes. A small proportion of ulcers are not associated with any recognized cause. This category includes ulcers that persist after successful treatment of H. pylori infection. One possible etiological factor deserves consideration. It is well known that a portion of the population develops severe scarring (keloids) after skin injury or abdominal surgery. Dense scarring is also found in association with some peptic ulcers and can interfere with normal healing by preventing the growth of new blood vessels. It is unknown whether this reflects specific pathogenic factors or is individual variation in response to chronic injury.

Ulcers are a consequence of concomitant diseases

It has long been suspected that PUD is associated with other medical conditions (Lamgman MJ, Cooke AR, 1976). However, the existence, mechanisms, and consequences of these combinations remain controversial.

Cirrhosis. The prevalence of PUP increases significantly in patients with cirrhosis (prevalence ranges from 10% to 49%) (Siringo S. et al, 1995). The mechanism of association of PUP with cirrhosis is unknown. Alcohol intake is not an explanation, as there is no convincing evidence that alcohol alone is a risk factor for peptic ulcers, and the association is evident in all forms of liver cirrhosis. Child-Pugh class is a risk factor (Kamalaporn P. et al, 2005).

Kidney diseases. The prevalence of PUP in chronic renal failure is controversial. The patient's condition and concomitant diseases may have contributed, including treatment with NSAIDs, antiplatelet agents, anticoagulants, and possibly H. pylori infection.

Organ transplantation. PUP remains a significant cause of transplant complications caused by several factors, including immunosuppression, glucocorticoid use, and cytomegalovirus infection (Benoit et al, 1993; Troppmann C. et al, 1995). Sirolimus may be an important risk factor (Smith AD et al, 2005). Whether screening for peptic ulcer disease before transplantation would be beneficial is unclear (Reese J. et al, 1991). A thorough history of the candidate's symptoms and previous peptic ulcer disease, assessment of H. pylori status (and antibiotic treatment) is necessary. Upper endoscopy - for patients with a previous history of ulcers or for those who have been treated for H. pylori, to confirm the absence of ulcers and H. pylori.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. A link between COPD and peptic ulcers has been suspected for many years. The incidence of COPD in patients with PUD is 2–3 times higher than in the general population, and peptic ulcers of both the stomach and duodenum occur in up to 30% of cases in patients with chronic lung disease (Langman MJ, 1976; Kellow JE et al, 1986 ; Stemmermann GN et al, 1989).

Rheumatic diseases. The prevalence of PUD increases markedly in patients with rheumatic disease due to the use of NSAIDs. It has been estimated that the highest prevalence of ulcers in patients on long-term NSAID treatment is approximately 20% (Hawkey CJ et al, 1997). However, many of these ulcers are identified endoscopically and will not manifest clinically. For this reason, attention should be paid to prophylaxis (eg, with PPIs or misoprostol), but only in high-risk patients.

Ischemic gastroduodenopathy

Gastric ischemia, manifesting as gastric ulceration, may result from localized or diffuse vascular insufficiency caused by systemic hypotension, vasculitis, disseminated thromboembolism (Tang S. et al, 2014), stress injuries due to burns, shock or sepsis (Thomas M., 2003). Among the causes leading to damage to visceral vessels, the leading place belongs to atherosclerosis (50–80%) and nonspecific aortoarteritis (20–30%) (Loginov A. S., Zvenigorodskaya L. A., 2000; Oinotkinova A. Sh., Nemytin Yu. V., 2001; Sokhach A. Ya., 2007; Yakovlev V. M. et al., 2009).

Acute mesenteric ischemia

An abrupt stop of blood flow in the mesenteric vessels leads to acute ischemia. The process can be caused by an embolus, arterial or venous thrombosis, vasospasm, or vasculitis. Embolic occlusion of the superior mesenteric artery occurs in more than half of all cases (Brandt LJ, Boley SJ, 2000). Most emboli originate from the heart and are potentiated by cardiac arrhythmia or decreased systolic function caused by coronary artery disease ( Table 4 ).

Table 4. Causes of acute mesenteric ischemia.

Several imaging techniques are used to diagnose acute mesenteric ischemia, including plain radiography, Doppler ultrasound, CT, and MRI. Unfortunately, such methods are not specific and sensitive enough for an accurate diagnosis (Lefkovitz Z. et al, 2002). Mesenteric angiography is the standard test for diagnosing occlusive arterial mesenteric ischemia. Its sensitivity and specificity are 75–100% and 100%, respectively (Walker JS, Dire DJ, 1996). In addition to being diagnostic, angiography has potential for treatment.

Rice. 4. Endoscopic picture of the duodenum in acute mesenteric ischemia. EGDS reveals edematous, ulcerated and necrotic mucosa of the postbulbar part of the duodenum with blood leaking from these places, suggesting gastrointestinal ischemia ( Fig. 4 ). Possible combined damage to the gastric antrum.

Laparoscopy has been used for several decades to diagnose acute surgical pathology of the abdomen. Diagnostic laparoscopy avoids unnecessary surgery in half of the cases. In addition, laparoscopy can be used as a second-look procedure for bowel conditions after resection or thrombolysis therapy. Although laparoscopy is well tolerated even in severely ill patients, the potential side effects of the surgically created pneumoperitoneum required for the study limit its use in patients with cardiac and respiratory failure. Another limitation is the inability to visualize the intestinal mucosa, especially in the early stages of ischemia. While upper and lower laparoscopy allows assessing mucosal perfusion.

The main limitation of endoscopy is the inability to accurately assess the depth of intestinal damage. Despite this, laparoscopy and endoscopy continue to play an important role in the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia.

Capsule endoscopy is preferred in the diagnosis of ischemic disorders, although current evidence of use is insufficient to make the test the first choice. The endoscopic spectrum of intestinal ischemia includes edema, ulcers with a segmental, circular manifestation (Katsinelos P. et al, 2008). However, capsule endoscopy has a number of disadvantages: the study takes a lot of time, it is impossible to accurately localize the pathology, take a biopsy, and carry out treatment. Thus, with the introduction of new technologies, new horizons are opening up for the use of capsule endoscopy in clinical practice, especially in the diagnosis and, probably, in the treatment of ischemic intestinal disorders.

Other causes of acute abdominal pain

Acute, severe pain may be caused by dissection or rupture of an aneurysm, which should be excluded in patients with vascular disease or signs of shock, especially if the pain is referred or originating from the back.

Heart and lung diseases , including acute myocardial ischemia, pericarditis, lower lobe pneumonia and pleurisy, should also be kept in mind. Pain in the left hypochondrium can be caused by pathology of the spleen, such as a heart attack or abscess, and is noted in myeloproliferative diseases, sickle cell anemia, or acute infection (for example, Epstein-Barr virus or malaria).

Acute hepatitis is a rare cause of acute pain (there will be other symptoms). In chronic viral hepatitis or cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and/or portal vein thrombosis, pain is usually chronic.

Thrombosis of the hepatic veins or inferior vena cava —Budd-Chiari syndrome is often associated with myeloproliferative syndromes, hypercoagulable states, or malignancy—causes of right upper quadrant pain, ascites, and abnormal liver tests. Doppler ultrasound of the hepatic veins can help in diagnosis.

Other rare causes of acute abdominal pain include Herpes zoster, hematologic factors such as Henoch-Schönlein purpura or acute leukemia, or manifestations of systemic diseases, including porphyria, diabetes mellitus.

Diagnosis of the disease

The study draws attention to the nature of pain with a stomach ulcer:

- When an ulcerative pathology of the gastric mucosa forms, a person’s pain begins within 15-30 minutes after eating food.

- The duodenum reacts to prolonged absence of food, so pain appears on an empty stomach and at night.

The examination takes place by:

- FGS (gastroscopy), where samples of mucous tissue around the area of the ulcer are taken

- Contrast radiography, bacterial culture

- Breath test

- Biochemical and general blood tests.

First of all, according to the analysis data, the presence of Helicobacter pylori bacteria on the walls of the mucous membrane of the stomach, small intestine and duodenum is checked.

Why does the disease occur?

The first reason why ulceration of the gastric mucosa develops is the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. It can be found in the digestive tract of almost every person without causing any problems. But the microorganism is activated if the following negative factors act:

- unhealthy diet, including fatty, fried, spicy, smoked foods;

- alcohol consumption;

- increased secretion or increase in the acid-base state of gastric juice;

- reduced activity of mucoproteins, bicarbonates, which prevent damage to the mucous membrane;

- adverse effects of nicotine when smoking;

- taking some medications, especially in an uncontrolled dose or in an excessive course not prescribed by a doctor (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, aspirin);

- development of benign and malignant tumors.

Gastric ulceration is often considered a symptom of an underlying disease. For example, during the development of a tumor. Then it is not a peptic ulcer that forms, but another condition. Treatment of the underlying pathology and symptomatic elimination of stomach inflammation are required.

Treatment of stomach ulcers

The medical team uses an integrated approach when prescribing a treatment program. Complex treatment of stomach ulcers allows you to quickly relieve pain symptoms, eliminate relapses, and eliminate dangerous complications, which are often accompanied by bleeding, gastric perforation, and the development of malignant tumors. Perforated gastric ulcer is a dangerous complication, which is characterized by the formation of a through hole (perforation) with the risk of developing peritonitis.

In addition to constant pain and the risk of the acute phase of the pathology developing into a chronic one, exacerbation of a stomach ulcer causes spasm of its walls - this is another serious complication in which food does not pass through the gastrointestinal tract.

Timely and complete therapy eliminates the risks of complications, reduces acidity with special medications and saves a person from problems. Surgical treatment is used only in exceptional cases.

Prevention for gastric ulcers

Knowing the causes of the pathology, doctors have developed a number of measures to help prevent the development of peptic ulcers in the gastrointestinal tract. Among the recommendations, the most common tips are:

- Proper nutrition

- Avoiding stressful situations

- Timely treatment of gastrointestinal diseases

- Monitoring the intake of anti-inflammatory drugs

- Reduce drinking and smoking.

Prevention and prognosis

In most cases, treatment of ulcers does not lead to complete recovery. However, if you adhere to the diet and undergo timely preventive examinations, the patient can lead a full life.

A mandatory rule for stomach problems is to follow a diet. During treatment and after its completion, it is recommended to exclude sauces, spices, fatty and smoked foods from the diet. You should not drink alcohol or sweet carbonated drinks.

It is important to make a choice in favor of lean meats, fish, liquid and pureed soups, and cereals. Stick to fractional meals - eat small portions five to six times a day. If you have problems chewing food, you should consult a dentist to restore your teeth. In addition to following the basic treatment regimen prescribed by a specialist, it is recommended to get enough sleep, reduce stress levels and walk more in the fresh air.

Factors leading to exacerbation of symptoms

An exacerbation of the disease does not happen without a reason. It is formed by external and internal factors that worsen well-being. Severe clinical symptoms manifest themselves under the influence of:

- changes in seasons, more often exacerbations occur in the spring or autumn;

- violation of the diet, which must be followed by the patient at any time of the year, even during remission;

- consumption of any doses of alcohol that are completely prohibited when ill;

- failure to take medications when feeling better, which is considered the biggest mistake among patients;

- active reproduction of Helicobacter pylori.

Patients often forget about seasonality. Therefore, it is recommended to start taking medications at the end of the winter and summer periods, even if there is no deterioration. This is the prevention of the formation of an acute period, leading to complications and the need for hospital stay.

It is important that food enters the gastrointestinal tract, even if a person feels unwell and feels sick. If there is no food in the stomach for a long time, the acid begins to act on the mucous membrane, which is also considered a negative factor. Therefore, ask your doctor what products are allowed to be used at this moment, so as not to provoke increased severity or other negative symptoms.

Features of a proper diet

To alleviate the condition and speed up recovery, you need to remember a few important rules:

1. You need to absorb at least 3000 Kcal per day. Also remember that food should contain more complex carbohydrates than fats and proteins, but the foods should be healthy.

2. Meals should be fractional, portions should not be large. You need to eat no more than 200 g of food per day at a time.

3. The diet should be gentle. It is important to avoid foods that are difficult to digest.

4. It is necessary to completely avoid fried foods, tobacco, alcoholic drinks, and soda.

5. Do not eat too hot or cold food - the temperature of the food should be at room temperature. This rule is very important to adhere to during periods of exacerbation.

6. If there are no contraindications, you should drink at least two liters of water per day.

7. You can only eat boiled, stewed and steamed dishes.

It is imperative to exclude from the diet foods that lead to mechanical irritation of the mucous membrane. These include:

- radishes, beans, grapes, raisins, dates (contain coarse fiber);

- stringy meat, poultry skin, cartilage;

- acidic foods, such as unripe fruits;

- foods that stimulate the secretion of the stomach - strong broths, smoked meats, pickled vegetables, eggs, butter dough, etc.

During the rehabilitation period, previously prohibited foods can be gradually introduced into the diet for a short period of time - this is a small workout for the gastrointestinal tract. However, you need to adhere to a therapeutic diet for at least a year after an exacerbation. This nutrition is aimed at accelerating the recovery of the stomach.

Classification

Gastric ulcers are divided according to clinical manifestations:

- acute form - develops quickly, affects significant parts of the organ;

- chronic form - forms gradually, long periods of remission are observed.

Classification by size of ulcers:

- small – less than 5 mm;

- medium – from 5 mm to 10 mm;

- large – 10-30 mm;

- giant - more than 30 mm in size.

Ulcers are divided according to the flow:

- atypical – proceed almost unnoticed and most often appear in adolescence;

- lungs – the pathology is mild, slight pain may be observed;

- moderate severity – relapses occur up to twice a year;

- severe - there is a continuous relapse, which is manifested by weight loss, metabolic problems, and the appearance of complications.

Ulcers are also classified by location:

- cardinal section of the stomach;

- subcardinal;

- antral;

- pyloric;

- body of the stomach;

- along the minor and major curvature.