Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCES) is not the most common phenomenon in gastroenterology. It is generally accepted that PCES belongs to the group of gallbladder diseases. In fact, this is not even a disease, but a collective name for a set of symptoms that appear immediately or shortly after surgery on the bile ducts or removal (resection) of the gallbladder.

Until now, both therapists and surgeons find it difficult to clearly determine the causes of the development of this syndrome. Doctors tend to use the term PCES only to make a preliminary diagnosis in operated patients1.

Symptoms of postcholecystectomy syndrome

At its core, PCES is a consequence of surgery for resection (removal) of the gallbladder. This means that after resection the patient may experience unpleasant symptoms, such as:

- dyspepsia or disruption of the normal functioning of the stomach, manifested in the form of bitterness in the mouth, nausea, bloating and intestinal upset;

- pain in the right hypochondrium with transition to the right collarbone or shoulder. The intensity of pain can vary, from unexpressed aching to acute burning;

- general weakness, pale skin (appears against the background of poor absorption of food and developing vitamin deficiency).

With PCES, other symptoms are possible due to exacerbated diseases:

- exacerbation of cholangitis - inflammation of the bile ducts - is expressed in a long-lasting temperature in the range of 37.1-38.0 ° C;

- Cholestasis (stagnation of bile in the liver tissue) can cause severe jaundice2.

FAQ

Is the development of PCES caused by surgical errors?

As we studied the mechanism of development of this process, it was found that errors in surgical intervention are in last place among the reasons for the formation of this condition.

Is there a cure for PCES?

The disease has a tendency to relapse, so treatment must be carried out in courses, sometimes for life.

How often does PCES develop after gallbladder removal?

On average, the disease develops in 30% of people who undergo cholecystectomy.

Is it possible to limit oneself to following a diet in the treatment of PCES?

Compliance with dietary recommendations is a mandatory, but not the only step in the treatment of this condition.

Are bile acid preparations used in the treatment of PCES?

Yes, if there are signs of a violation of the composition, formation and secretion of bile.

Reasons for the development of postcholecystectomy syndrome

The causes of postcholicystectomy syndrome and its development are often associated with disruption of the normal functioning of the sphincter of Oddi (orbicularis muscle). The sphincter of Oddi is a smooth muscle that is located in the lower part of the duodenum and is responsible for regulating the supply of bile and pancreatic juice to the duodenum3.

If we consider that PCES most often affects patients who have undergone surgery to remove the gallbladder4, then the mechanism of occurrence of this syndrome can be explained as follows:

- after the operation, the sphincter, which normally opens when the gallbladder is full, does not receive a signal about filling, as a result of which it is almost constantly under tension;

- due to the absence of a bladder, bile enters the duodenum in a diluted state, which increases the pressure inside the intestinal walls. In addition, bile itself has a bactericidal effect and a change in its composition can lead to intestinal infection5.

But sphincter of Oddi dysfunction may not always be caused by removal of the gallbladder. Sometimes the cause of the syndrome is advanced gastrointestinal diseases* (chronic colitis or gastritis, peptic ulcer) and chronic pancreatitis) - a disease of the pancreas, as well as errors in preoperative examination.

Diet features

Restoring normal bile production processes is possible with the help of a strict diet. A balanced diet and daily routine will help avoid possible complications. On the first day after surgery, complete fasting is recommended. From the second day, the doctor will allow you to drink light drinks, rosehip decoction. Then fermented milk foods, broths, etc. are introduced. Usually a new dish is added to the diet once every two days.

There are several basic rules of nutrition during the recovery period:

- small portions and 5-6 meals per day;

- only warm food and drinks - too cold or hot foods can irritate the digestive tract;

- taking a sufficient amount of fluid - at least 1.5-2 liters per day;

- refusal of fatty, spicy foods, marinades and pickles, smoked meats;

- the right choice of cooking methods - stewing, baking, boiling;

- refusal of soda, alcohol, fresh bread, baked goods and confectionery.

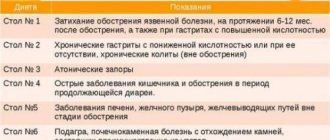

Table No. 5 according to Pevzner can be taken as a basis. Even strict adherence to a diet may not completely solve the problem, but following your doctor’s recommendations is very important. It is nutritional disorders that become a common cause of complications.

Diagnosis of postcholicystectomy syndrome

Difficulties in accurately determining the causes that led to the development of PCES and the vagueness of the very definition of the syndrome require a thorough examination of the patient. In order to choose the right treatment, it is necessary to clearly establish what led to the appearance of PCES.

That is why effective diagnosis of postcholicystectomy syndrome includes several methods:

- collection of anamnesis data - the doctor carefully studies old medical reports and records, paying close attention to preoperative diagnostics and the protocol of the operation;

- clinical examination of the patient;

- laboratory tests - clinical and biochemical blood test, stool test for protozoa and worm eggs, general urine test;

- ultrasonography;

- endoscopy of the bile ducts;

- Magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography of the abdomen6.

Introduction

In the last few decades, gallstone disease (GSD) has become perhaps one of the leading gastroenterological diseases (10–15% in the adult population), for which a lot of planned and emergency surgical interventions are performed all over the world [3]. In the USA alone, about 1 million new cases of cholelithiasis are diagnosed annually, and treatment costs reach $6 billion per year [3, 4]. In Russia, about 200 thousand cholecystectomies are performed annually, mostly laparoscopically [1].

On average, only 20% of patients with cholelithiasis manifest symptoms [5]. In the case of symptomatic cholelithiasis, surgical intervention leads to a decrease in the severity of dyspepsia and biliary pain in a significant number of patients. However, many of them (about 40%) do not experience relief after cholecystectomy or symptoms may appear for the first time [6–9]. Symptoms of pain and dyspepsia after cholecystectomy persist with great variability (in 5.6–57.3% of patients) or appear for the first time after surgery (in 12.0–38.6% of patients) [10–13]. Thus, up to half of the patients who underwent cholecystectomy at different times from the moment of the operation complain of abdominal pain and symptoms of gastric and intestinal dyspepsia, explained by both organic and functional causes [1].

Currently, there is an obvious lack of knowledge about the most effective treatments for postcholecystectomy disorders, resulting in widely varying therapeutic approaches for these patients. The purpose of this review was to summarize the available data on the treatment of patients with pain and spasms after gallbladder (GB) removal, as well as to justify the relevance of additional clinical research in this therapeutic area.

Definition of postcholecystectomy syndrome

Postcholecystectomy syndrome (PCES) only at first glance looks like a simple problem; the difficulties in understanding the syndrome begin directly with its definition. The first works, one way or another describing pathological conditions after cholecystectomy, appeared abroad in the late 1930s. [14–16]. The most significant is the first series of observations presented by J. Hellstrom in 1938 (KK Nygaard), numbering 1041 patients, 30% of whom had cramping abdominal pain after removal of the gallbladder, similar to what they had before surgery. Only 9 patients were diagnosed with choledocholithiasis, and even less often acute pancreatitis was diagnosed. The causes of pain in other cases could not be explained; the author called the identified pain “postcholecystectomy colic” [16].

The next largest series of observations was presented by H. Doubilet only in an oral report at a meeting of the surgical section of the New York Academy of Medicine in April 1943, which was presented in detail in a subsequent review by R. Colp [17]. The series consisted of 253 patients who underwent cholecystectomy and were observed for a period of 1 to 7 years. The author reports that 40% of patients had postoperative symptoms, often similar to symptoms before surgery. It was in these two works [16, 17] that the term “postcholecystectomy syndrome” was first encountered, explaining a complex of various disorders after cholecystectomy, most of which due to the absence of organic causes (for example, choledocholithiasis, stenosis of the terminal part of the common bile duct, etc.), according to the authors acknowledge that they are functional. Such disorders are accompanied by recurrent spastic pains of the “colic” type, which are based on dyskinesia of the sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract, intestines and borderline mental disorders in some patients.

What is interesting: even then, in an open observational study, it was noted that more often PHES develops during the removal of a functioning gallbladder (acalculous cholecystitis or calculous cholecystitis without pronounced fibrosis of the gallbladder wall) [16, 17]. The revealed facts formed the basis for the empirical use of nitrates and atropine to relieve the spasm underlying PCES in the absence of organic causes of pain after cholecystectomy [17]. A series of simple descriptive studies of those years made it possible to develop indications and discuss the theoretical possibilities of papillotomy, based on experimental work from the beginning of the last century.

Subsequently, the term PCES became established in the scientific literature and was regularly found in works of the 1940–1970s. [18–22], whose number increased by the mid-1970s. reached 100. It is interesting that the first domestic work [23] reviewed in international databases contains skepticism towards this term. What is even more curious: since the late 1960s. The number of English-language articles on the topic of PCES in the most respected journals begins to fall to almost zero by the 1980s, while the number of works from Eastern Europe and the USSR increases significantly. Already in the 1980s. In authoritative English-language journals, the term PCES is replaced by postcholecystectomy pain [24, 25], papillary dysfunction [26], and even uses the terminology of the 1930s. – “biliary dyskinesia” [27].

Today, it is absolutely clear that the complexity of studying and verifying postcholecystectomy disorders, the similarity of symptoms with organic changes and functional disorders have led to the fact that the term PCES in Western countries by the mid-1980s. stopped being used. In international practice, there is still no unified term “postcholecystectomy syndrome”, since it is incredibly difficult to determine the exact mechanism and root cause of pain and dyspepsia that occur at different time periods after cholecystectomy. However, paradoxically, the term PCES was included in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (Code K91.5) and was extremely popular in the USSR, and now in Russia. Wide acceptance of the term in the 1970s and 1980s.

in the USSR it was no coincidence due to the growing number of cholecystectomies and insufficient understanding of the possible consequences of the intervention - from functional maladaptation of the biliary tract and even the entire digestive system to gross organic changes.

In Russia today, by PCES we mean many different diseases and conditions that arise in patients after cholecystectomy and theoretically can be associated with it. It was the impossibility of combining organic changes and functional disorders under a single diagnosis that led to the disappearance of the term abroad, where any abnormalities in a patient after cholecystectomy, theoretically associated with it, are considered a “condition after cholecystectomy” [28, 29]. According to clinical indications in risk groups and in the presence of markers of organic changes, a diagnostic search for the cause is carried out, otherwise a diagnosis of “sphincter of Oddi dysfunction” is established, according to the Rome criteria of the III revision [30–33].

For an objective idea of the structure of nosologies that cause gastrointestinal symptoms after cholecystectomy, one should refer to recent clinical studies. Thus, in a study conducted in Romania [34], patients with symptoms of pain and dyspepsia after removal of the gallbladder were examined. All patients underwent a biochemical examination - determination of the levels of bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, transabdominal and endoscopic ultrasound, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and manometry, i.e. a full range of methods to exclude gross organic pathology of the hepatopancreatobiliary zone. It turned out that most of the patients one way or another had an organic pathology - choledocholithiasis, cystic duct stump. In a third of patients, the cramps were caused by causes that did not require any surgical intervention: sphincter of Oddi dysfunction or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

Another study conducted in the UK [35] to assess the incidence of diarrhea in patients after cholecystectomy reported that 17% had new-onset diarrhea after surgery. The authors cite young age as one of the most reliable risk factors for the development of diarrhea. One of the causes of secondary functional disorders of the intestine after cholecystectomy is malabsorption of bile acids and the development of secretory diarrhea due to excessive and asynchronous flow of unconcentrated bile into the lumen of the intestinal tube. The pathophysiology of secretory diarrhea is also based on the accelerated passage of contents through the small and large intestines, accompanied by hypermotility of intestinal smooth muscles. Hypermotility and spasm with the appearance of pain are very similar pathophysiological conditions. Visceral hypersensitivity, spasm (pain) and diarrhea form IBS-like symptoms in some patients after cholecystectomy. Personality characteristics in some of these patients are a risk factor for the persistence of symptoms.

It is important to note another study that assessed the quality of life of patients after cholecystectomy using the GQL (Gastrointestinal Quality of Life) questionnaire in 158 patients scheduled for cholecystectomy [36]. Monitoring them 6, 12 weeks and 2 years after cholecystectomy showed that the operation generally improves the quality of life of patients: the average score increased significantly 6 weeks after surgery, the picture persisted after 3 months. However, 2 years after the operation, the authors noted a deterioration in the quality of life, apparently due to the development in some patients of certain abnormalities that can be designated as PCES.

In addition, to determine how IBS symptoms impact cholecystectomy outcomes, all patients pre-cholecystectomy were assessed for compliance with IBS criteria. It turned out that 32 (20.3%) patients had IBS before cholecystectomy. The quality of life of these patients after surgery was significantly worse compared to other patients, and their positive outcome from cholecystectomy was much less. The presence of each Manning symptom reduced the quality of life by 5 points compared with the main group (statistically significant). Compliance with the Rome II criteria for IBS decreased quality of life by 12 points compared with the general group of patients. Thus, if a patient has IBS before surgery, it is very likely that it persists and possibly gets worse after surgery. It is from such a patient that we can most likely expect repeat visits to the surgeon and gastroenterologist after surgery with complaints of symptoms of pain and dyspepsia, bowel disorders and deterioration in quality of life [36].

Pathophysiology of PCES

Based on the many organic and functional causes of pain and dyspepsia after cholecystectomy, in the pathophysiology of PCES it is necessary to distinguish five main blocks of factors with different pathophysiology, but a number of common mechanisms:

- pain, dyspepsia and other symptoms caused by organic pathology associated with cholelithiasis and/or cholecystectomy (cystic duct stump, choledocholithiasis, acute biliary pancreatitis, stricture of the common bile duct and major duodenal papilla, etc.);

- clinical manifestations of another organic pathology, theoretically not related to cholecystectomy (de novo tumors of the digestive organs);

- dysfunction (spasm) of the sphincter of Oddi, which occurred initially or appeared/worsened after cholecystectomy (the so-called true PCES);

- digestive disorders due to changes in the properties and secretion of bile, called “biliary insufficiency.” Although this term is not yet generally accepted, however, deficiency of bile acids and asynchrony of bile secretion can contribute to the development of various pathological conditions that determine the clinical picture of postcholecystectomy disorders (exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, duodenogastric reflux, bacterial overgrowth syndrome [SIBO] in the small intestine, etc.) ;

- other functional disorders of the digestive system (IBS, functional dyspepsia, gastroesophageal reflux disease).

To better understand the pathophysiology of postcholecystectomy disorders, we should focus on the functions of the gallbladder (lost after cholecystectomy) [1]:

- evacuation (during the digestive period it ensures the release of bile into the duodenum);

- concentration and reservoir (only concentrated bile has the best ability to participate in digestion and provide a bactericidal effect);

- absorption (absorption of individual components of bile as compensation

- satorious reaction in case of their excess);

- secretory (secretion of mucus by the glands of the cervical region, which facilitates the flow of bile into the gallbladder and the evacuation of bile from it);

- hormonal (secretion of anticholecystokinin, which has a modeling effect on the sphincter of Oddi).

The sphincter of Oddi also has important functions related to the work of the gallbladder: it regulates the outflow of bile and pancreatic juice into the duodenum, prevents reflux of duodenal contents into the common bile duct and the main pancreatic duct, ensures the accumulation of bile in the gallbladder between meals, since it is capable of overcome the secretory pressure of the liver and performs synchronous work with the gallbladder [1].

In the pathophysiology of postcholecystectomy disorders, oddly enough, there are still a number of the following unanswered questions:

- does the volume, composition and viscosity of bile produced change after cholecystectomy is performed;

- how does the pressure in the bile ducts change after cholecystectomy, especially at night, when the storage and concentration functions are realized with a functioning bladder;

- how the motility of the biliary tract and upper digestive tract changes;

- does the sphincter of Oddi react to the absence of the gallbladder;

- How does the absence of pancreas affect pancreatic function?

In order to answer these questions, serious research is required, which, apparently, is very difficult to carry out methodologically, and in light of the breadth of individual characteristics of each person and a host of other parameters seem generally unrealistic.

Some studies note that after cholecystectomy the tone of the sphincter of Oddi increases, and the hypertonicity persists for quite a long time - two years and probably more. In the case of prolonged spasm of the sphincter of Oddi, the development of biliary hypertension, cholestasis, and pain can be assumed. However, this is not always observed clinically. We are probably talking about the variable severity of spasm and related processes.

So, the loss of the gallbladder with the loss of its functions and the resulting development of dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi leads to a decrease in the quality and quantity of flowing bile and pancreatic secretion into the duodenum, which is not always fully compensated by the work of other digestive organs. In this regard, real conditions are created for disruption of the digestion process. The pathogenesis of PCES is partly due to the loss of functions of the gallbladder - the absence of evacuation and concentration functions will determine the disruption of lipolysis processes in the small intestine and a decrease in the bactericidal properties of bile. Continuous bile leakage will also cause digestive dysfunction, as well as the formation of biliary reflux and the development of hypertonicity of the sphincter of Oddi [1].

Under the influence of altered microflora of the small intestine, bile acids undergo premature deconjugation, which is accompanied by damage to the mucous membrane, the development of duodenitis, reflux gastritis and esophagitis. In turn, duodenitis is accompanied by duodenal hypertension and duodenal dyskinesia, which contributes to the persistence of pathological reflux.

It should also be noted that cholelithiasis, the course of which ultimately led to cholecystectomy, is often accompanied by other concomitant diseases of the digestive organs, primarily the pancreaticoduodenal zone, which further aggravates the quality of digestive processes. Thus, long-term cholelithiasis is accompanied by biliary pancreatitis in 60–80% of cases [2]. After cholecystectomy, cholecystokinin levels are known to decrease. Starting from the first day and up to 5 years after cholecystectomy, there is a 50-fold decrease in it, which more than doubles the risk of developing sphincter of Oddi dysfunction [1].

Clinical picture

Thus, pain syndrome after cholecystectomy, which is the main reason for the decrease in the quality of life of patients after surgery, comes from the multifaceted pathophysiology of PCES presented above. The main cause of pain is the functional restructuring of the sphincter apparatus of the biliary tract after cholecystectomy. Already within the first month after surgery, hypertonicity of the sphincter of Oddi is detected in 80–90% of cases [1].

Today, the Rome consensus well represents the clinical picture of three types of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction: biliary, pancreatic and mixed [33].

With isolated dysfunction of the common bile duct sphincter, biliary pain occurs, localized in the epigastric region or right hypochondrium with irradiation to the back and right scapula. When the sphincter of the pancreatic duct is predominantly damaged, pancreatic pain appears, localized in the epigastrium and left hypochondrium, radiating to the lumbar region. With spasm of the common sphincter, combined biliary-pancreatic pain is observed, often described as “girdling pain.”

Treatment tactics

Treatment approaches are based on timely and correct identification of the cause of pain and dyspeptic disorders after cholecystectomy. The primary task is to exclude organic pathology of the biliary tract, which may be the cause of complaints: choledocholithiasis, biliary strictures, tumor lesions, etc. The presence of such changes dictates the need for surgical treatment.

When excluding organic causes of pain and dyspepsia in patients who have undergone cholecystectomy, in combination with a number of indirect signs, one should think about the functional nature of the pain:

- current symptoms existed before surgery and reappeared in the postoperative period with the same or greater severity;

- there is a long-term non-progressive course;

- use of psychotropic drugs before surgery;

- compliance of complaints with the criteria for functional disorders of the gastrointestinal tract - gastrointestinal tract (dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, IBS).

The exclusion of organic causes of pain and dyspepsia in patients who have undergone cholecystectomy serves as an indication for conservative treatment - as a rule, always combined and currently not fully supported by recommendations.

The main means, according to various authors [37–39], should be drugs that affect intestinal motility and the sphincter of Oddi, including antispasmodics. There are reports of the high effectiveness of calcium antagonists (nifedipine) and nitrates [40], however, these drugs do not have registered indications for the treatment of gastroenterological diseases in the Russian Federation.

Additionally, medications for the treatment of SIBO, duodenogastric reflux, pancreatic enzymes, etc. may be prescribed. There are no unified pharmacotherapy regimens due to the frequent combination of various functional disorders in a variety of combinations that can alternate over time, the presence of optional but frequent concomitant syndromes (SIBO, etc.). It should be recognized that in case of proven dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, resistant to conservative treatment for 3 months, endoscopic treatment (papillotomy and stenting) is possible.

The choice of antispasmodic is carried out empirically in routine practice, since it is impossible to verify the type of motor disorders and conduct pharmacological tests with different drugs. Moreover, due to the combination of functional disorders in one patient, it is difficult to separate complaints caused by dysfunction of the sphincter of Oddi, duodenogastric reflux, accompanying IBS. Therefore, agents are selected that can eliminate spasm both in the biliary tract and in the intestines.

Prerequisites and relevance of conducting a post-marketing clinical trial

A meeting was held in Moscow on June 18, 2013 to discuss and agree on a clinical trial protocol to study the effects of mebeverine in patients with symptoms of cramping abdominal pain and dyspepsia after cholecystectomy. All co-authors of this article created a working group, during which the following facts were highlighted.

So, PCES is a heterogeneous group of diseases that are mainly manifested by abdominal pain and are in one way or another associated with cholecystectomy. The term “postcholecystectomy syndrome” is not entirely accurate, because it describes both biliary and non-biliary diseases, organic and functional. Symptoms of PCES are also nonspecific; they manifest themselves as pain in the epigastrium and right hypochondrium, dyspepsia and stool disorders associated with abdominal pain.

There is original mebeverine (Duspatallin®, Abbott) on the Russian pharmacological market. According to the instructions for medical use, it has two indications for use: IBS and symptomatic treatment of spasms of the gastrointestinal tract (including those caused by organic diseases). Thus, spasm of the sphincter of Oddi caused by cholecystectomy is also an indication for the use of mebeverine. In clinical studies, the drug demonstrated effectiveness in IBS [41–44] due to the known mechanism of action of spasm relief in combination with an additional mechanism that prevents complete relaxation of the cell due to blockade of calcium current [45]. In a placebo-controlled study, mebeverine was shown to significantly weaken colonic motility [46]. Based on these data, we can assume that the use of mebeverine can not only reduce the severity of pain caused by spasm, but also slow down transit through the colon, thereby reducing intestinal manifestations of postcholecystectomy disorders.

Among the published studies on the use of mebeverine in biliary pathology, there are only small open domestic studies of patients with PCES, cholelithiasis and chronic cholecystitis [37–39, 47]. Of greatest interest is the study [39] of the use of mebeverine to prevent the development of PCES before and after cholecystectomy, which showed a decrease in the severity of symptoms. Unfortunately, despite the positive data on the possibility of using mebeverine in biliary pathology, none of the studies cited above were multicenter.

Thus, we now understand the need to obtain additional scientific data on a broad patient population in a multicenter study. This is all the more important because, from the standpoint of modern science, we do not have enough data to form the basis for pharmacotherapy of postcholecystectomy disorders. The approaches developed today abroad are based primarily on endoscopic treatment methods - papillosphincterotomy and common bile duct stenting, with a clear shortage of publications on the conservative management of such patients. Therefore, in the planned study, it is very important for us to show the effect of conservative therapy on the patient’s quality of life, as well as to obtain additional data on the effectiveness and safety of mebeverine for patients with intestinal disorders concomitant with cholecystectomy. Since there are no international publications on this topic, the results obtained during the planned study will be published in 2014–2015. not only in Russia, but also abroad.

The preliminary title of the study protocol is: “Post-marketing observational study of the effectiveness of mebeverine (Duspatalin®) in patients with sphinketer of Oddi dysfunction after cholecystectomy (Odissey study).”

Conclusion

In conclusion, the following conclusion must be made. Firstly, there are many patients with unsatisfactory quality of life results after cholecystectomy due to recurrent cramping abdominal pain, the number of which continues to increase. It is for such patients that it is necessary to evaluate the possibility of using mebeverine. If the patient has typical clinical manifestations and no signs of organic pathology, it is intended to evaluate the effect of mebeverine on symptoms and quality of life, which will allow us to answer the question of how effective conservative therapy is for such patients. This study is especially relevant because there is currently insufficient data on the management of patients with gastrointestinal spasticity after gallbladder removal.

It seems to us that the results of this study will be in real demand in routine clinical practice; these data will live and be used by doctors for the benefit of our patients.

The authors of the article are members of the Council of Experts on the topic “Working Group: Quality of Life after Cholecystectomy,” organized by. The authors are grateful for the assistance provided in publishing the results of the Council of Experts (payment of the publication fee).

Treatment of postcholicystectomy syndrome

Since PCES is not an independent disease, treatment of the syndrome is always determined by its causes. Not knowing how to properly treat postcholicystectomy syndrome can only aggravate the condition and increase unpleasant symptoms.

The principles of treatment for PCES include two key points:

- collection of anamnesis data - the doctor carefully studies old medical reports and records, paying close attention to preoperative diagnostics and the protocol of the operation;

- eliminating the causes of the syndrome;

- prevention and treatment of suspected complications.

Treatment is mainly based on:

- diet therapy;

- drug treatment;

- surgery (according to indications)7.

Together with comprehensive treatment, these measures can reduce the severity of symptoms of PCES8.

Treatment of hologenic diarrhea

The main goals of therapy are to restore the normal biochemical composition of bile, the function of the biliary tract and minimize the continuous effect of bile acids on the small intestine. In most cases, following the recommended regimen and diet leads to recovery. The need to prescribe medications is determined by the doctor in each specific case.

Postoperative regimen

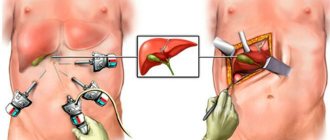

After laparoscopic surgery, on the first or second day you are allowed to walk for 30-40 minutes daily, do breathing exercises and exercise therapy. Lifting weights more than 5 kg in the first 7-10 days is contraindicated. After 4-6 months, the range of physical activity expands, running and working out the abdominal muscles are added. The recovery time is determined by the presence or absence of complications, the initial level of physical fitness, and concomitant pathology.

Features of nutrition with a removed gallbladder

To prevent bile from accumulating in the ducts, food should be eaten frequently and in small portions. The optimal number of meals is 5-7 per day. The volume of the main portion is 200-250 ml. Be sure to have 2-4 snacks. Fats are limited to 60-70g per day.

For hologenic diarrhea in the early postoperative period, American therapists recommend the “BRATTY” diet. It includes bananas, rice, apples (preferably baked), weak tea, dry day-old bread and biscuits, and natural yogurt. It is important to drink enough fluids to prevent the opposite problem - constipation.

Following a number of recommendations will help improve the quality of life after surgery:

- Reduce the amount of fatty and fried foods. Steam, stew or boil food. There is no need to completely eliminate fats from your diet. In one meal, 3 grams of fat are digested. Larger amounts cause dysmotility and bloating.

- Increase fiber intake over 2-4 weeks. Include cereal porridges, whole grain flour products in your diet, add butter and vegetable oil. A sharp increase in fiber leads to gas formation.

- For protein products, low-fat fish (hake, pollock) and lean meat (chicken, quail, rabbit, beef) 1-2 times a week are recommended. Reduced-fat dairy products (cottage cheese, kefir, yogurt) are offered for snacks and dinner.

- The diet should include vegetables, fresh stewed and baked. Fermented and pickled foods are not recommended to prevent bloating.

- Coffee worsens the symptoms of diarrhea, so it is better to avoid it. Replace sweets with non-sour fruits and honey.

Drug correction of diarrhea

Diarrhea syndrome should be treated depending on the severity and accompanying complaints. To prevent electrolyte disturbances in the acute period, rehydration solutions are prescribed (Regidron, Ionica, Bio Gaia ORS). Probiotics (Enterozermina, Enterol, Linex) help normalize the intestinal microflora. To treat painful spasms, antispasmodics (Mebeverine hydrochloride) and choleretic drugs are prescribed. Herbal preparations containing silymarin (Gepabene, Essentiale, Karsil, Darsil) normalize liver function.

If signs of inflammation are detected, antibiotics are required (Erythromycin, Clarithromycin, Ciprofloxacin). To weaken motor skills, loperamide (Imodium, Lopedium) is used. Enzyme deficiency can cause diarrhea, flatulence, and heaviness in the stomach. Creon (Pangrol, Panzinorm, Ermital) helps replenish enzyme deficiency and facilitate the digestion of food. With diarrhea, the absorption of nutrients is limited, so vitamin and mineral complexes containing omega 3 fatty acids, magnesium, and vitamins B and C are prescribed.

Without lifelong adherence to a diet and regimen, drug therapy is ineffective.

Irritation from diarrhea

Hologenic diarrhea causes damage to the skin of the anus from bile and irritating acids. A few rules will help alleviate the painful condition.

- After bowel movements, do not rub, but soak. Use baby wipes instead of toilet paper.

- Apply a thin layer of baby protective cream against diaper dermatitis to the anus. The barrier will protect irritated skin from the action of bile acids.

- Avoid hot spices and herbs. Stimulating bile secretion will lead to more irritation.

- Keep a food diary. This way you can mark dishes that provoke an unpleasant symptom.

The use of enzyme preparations in postcholicystectomy syndrome

In some cases, PCES may be accompanied by disorders of the digestive system. This is due to the fact that food intake becomes a signal for the production of bile and pancreatic enzymes. If the signal does not arrive or arrives intermittently, subsequent events are also disrupted. As a result, food is not processed properly, and the body does not receive enough nutrients. This can affect the general condition of the body and manifest itself as heaviness after eating, discomfort, bloating or diarrhea.

Enzyme preparations have been developed to support digestion; they deliver enzymes from the outside to compensate for their lack in the body. The flagship among such drugs is Creon®.

The drug is available in the form of capsules containing hundreds of small particles - minimicrospheres. They do not exceed 2 mm in size, which is recorded as recommended in world and Russian scientific works9,10. The small particle size allows Creon® to recreate the digestive process as it was intended in the body, and thereby cope with unpleasant symptoms. Dosages of the drug are usually selected by a doctor, however, in accordance with modern recommendations, the starting dosage is considered to be 25,000 units10.

To learn more

An important stage in the treatment of PCES is enzyme therapy, because In many cases of PCES, pancreatic function is impaired and enzyme deficiency occurs11. Because of this, digestive problems arise, manifested in the form of unpleasant symptoms such as abdominal pain, heaviness in the stomach, flatulence and diarrhea. In addition, the lack of enzymes affects the quality absorption of nutrients: the body does not receive the necessary vitamins and minerals.

Creon® is a modern enzyme preparation that replenishes the deficiency of its own enzymes and promotes better absorption of food and improved digestion. More information about the drug can be found here.

Means to combat diarrhea after cholecystectomy

Poor nutrition leads to diarrhea.

After the operation, the patient is in the hospital, doctors monitor him and correct any complications that arise in a timely manner.

The food there is exclusively dietary; patients are given medications that slow down bowel function, and medications are administered that help restore the volume of lost fluid and replenish the supply of vitamins and minerals.

Therefore, the first weeks after the operation are normal. But after discharge the problems begin. Typically, patients who are tired of a monotonous diet allow themselves a lot.

They believe that the problems are behind them, so they begin to eat a lot of excess food. They simply return to their normal diet. It should be recalled that in most cases this operation is performed on overweight people.

This means that they have not limited themselves in food for many years, believing that everything will pass without a trace. Even after the operation, it is difficult for them to readjust, they simply cannot deny their appetite and eat a lot of unhealthy fatty foods.

After discharge, they immediately pounce on food, wanting to make up for lost time. By eating forbidden foods, they make diarrhea simply inevitable.

Along with diarrhea comes deterioration of the condition, loss of fluid and other negative consequences.

Since food is not digested during diarrhea, hunger does not go away. This leads to further uncontrolled food consumption and, as a consequence, aggravation of the situation as a whole; therefore, only the strictest diet can be considered the main “cure”.