Stomach in dogs and cats

The stomach in cats and dogs is an independent organ that is part of the digestive tract.

Like any organ, the stomach is susceptible to specific diseases, each of which has its own name, etiology and pathogenesis. One of the most important tasks of a clinician faced with a stomach disease is to determine which particular nosological unit he is dealing with, since both the diagnostic plan and the tactics of further treatment depend on this. Typically, gastric disease, like many other gastrointestinal diseases in dogs, results from inflammation, ulceration, neoplasia, or obstruction. The clinical manifestations of stomach diseases are similar: most often it is vomiting and/or retching, hematemesis, melena, belching, hypersalivation, abdominal discomfort, weight loss (in chronic diseases). Gastritis, which will be discussed in this material, is only a part of the many diseases associated directly with the stomach. Most often, veterinarians deal with the following stomach pathologies:

- inflammation (gastritis);

- acute dilatation;

- volvulus;

- erosions and ulcers;

- neoplasia;

- motility disorders.

Gastritis is one of the most frequently diagnosed diagnoses when a patient is admitted with a complaint of acute or chronic vomiting. Meanwhile, acute/chronic vomiting syndrome is extremely common in small animals and in the vast majority of cases has many other causes. A clear understanding of the cases in which the diagnosis of “gastritis” is legitimate is necessary. In addition, since acute/chronic vomiting syndrome can occur for a variety of reasons, and making a diagnosis in this case is not an easy task, it is very important to follow a generally accepted diagnostic plan to avoid errors in diagnosis and, subsequently, in the treatment of the patient.

Introduction

The problem of chronic gastritis is interesting and multifaceted.

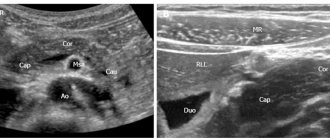

Perhaps, none of the diseases of the gastrointestinal tract has undergone such definitive changes from “chronic phlegmosia” and the cause of death in the Napoleonic era (Broussais F., 1808) to a chronic infectious disease of the gastric mucosa (GMU), caused primarily by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori (Marshall B. and Warren J., 1984), from a functional disease to the formation of its “morphological essence”. Today we are talking about chronic gastritis as the most common disease of the upper digestive tract, which is morphologically characterized by inflammatory, dystrophic and dysregenerative processes in the coolant [1, 2]. To make a correct diagnosis, it is first necessary to clarify the topic of the lesion, because this has an impact on the choice of treatment tactics and patient survival. Secondly, we will definitely examine the morphological features of the infiltrate, namely the presence, extent (antrum, body of the stomach) and severity of atrophic changes in the coolant (Fig. 1).

The key stage on the path to diagnosis is establishing the etiology of the disease for its further treatment and developing a plan for monitoring the patient. Undoubtedly, H. pylori causes progressive damage to the gastric mucosa and is now recognized as a causative factor in a number of serious diseases, including peptic ulcer disease and its complications, as well as gastric cancer [3]. But we know that back in 1947, in his monograph “Gastritis,” R. Schindler, analyzing and comparing endoscopic and histological pictures of damage to the coolant, wrote about its other possible causes (duodeno-gastric reflux, impaired blood supply, etc.).

The key point in the analysis and systematization of the etiological factors of chronic gastritis, assessment of the relationship between structural and functional changes, and the pathomorphological picture was introduced in 2015 by the Kyoto consensus [4]. The importance of not only H. pylori infection, but also other forms of gastritis, including autoimmune gastritis (AIG), was emphasized.

The purpose of this publication was to update information on the diagnosis and treatment of AIH in medical practice (general practitioner and gastroenterologist) using a specific clinical example.

Clinical case

Patient B., born in 1967, consulted a doctor with complaints of heaviness, bursting pain in the epigastric region 30 minutes after eating, burning in the epigastrium, heartburn after eating extractive food. The patient's weight is stable, her appetite is preserved, her stool is regular, formed, and without pathological impurities. There were no complaints from other organ systems.

From the medical history, it is known that complaints of heaviness and burning in the epigastric region first appeared in 2016. An outpatient esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EFGDS) revealed changes in the form of catarrhal distal esophagitis, cardial insufficiency, gastritis with the presence of erosions in the body and upper third of the stomach ( the changes are weak, against the background of subatrophy of the antrum mucosa), cicatricial deformation of the duodenal bulb (DU), bulbitis. According to the patient, no endoscopic examination of the stomach had been previously carried out, and therefore it is not possible to establish the duration of the duodenal ulcer. A morphological study of gastrobiopsy taken from the antrum revealed superficial fragments of the mucous membrane of the antrum of the stomach with the presence of weak mononuclear inflammatory infiltration of the lamina propria; H. pylori colonization was not detected. Based on the results of general and biochemical blood tests, no pathology was identified. The patient was observed with a diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease, non-erosive form, uncomplicated course. Cardia failure. Chronic H. pylori is a negative gastritis with mild atrophy of the antrum and the presence of erosions of the body and upper third of the stomach. History of duodenal ulcer: cicatricial deformation of the duodenal bulb.” A conversation was held about possible side effects from taking drugs that have a damaging effect on the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum (acetylsalicylic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) [5], which the patient denied taking. The patient received proton pump inhibitors and bismuth tripotassium dicitrate preparations in a standard dosage for 4 weeks, which led to complete healing of the erosions according to the results of the control endoscopy. It is recommended to repeat EGD after a year with taking biopsies according to the standard protocol to monitor coolant atrophy.

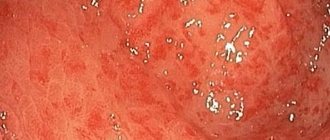

During EGD in December 2022, it was revealed: the esophagus is freely passable, the lumen is round in shape, the folds are longitudinal, they are straightened by air, the walls are elastic, the mucous membrane is pale pink, the cardia is gaping; the stomach is in the shape of a medium-sized hook, freely expands with air, the walls are elastic, the folds are tortuous, medium in height, peristalsis is moderate, can be traced in all sections, the coolant is patchily hyperemic, in the cardiac section there is fine-focal hyperplasia of the mucous membrane of 2–3 mm (Fig. 2), pylorus in the form of an oval opening, closes; The duodenum is a rounded bulb, the intestinal lumen is oval, the folds are circular, the mucous membrane of the proximal part is moderately hyperemic, the major duodenal papilla is not changed, in the descending branch along the lateral edge there is a raised-flat formation up to 5–6 mm (Fig. 3), the surface is hyperemic . Conclusion on EGD: cardial failure, diffuse superficial (erythematous) gastritis, small focal hyperplasia of the cardia of the stomach, duodenitis, focal hyperplasia of the duodenum.

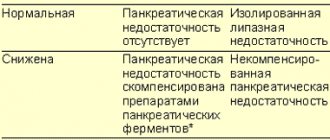

Endoscopic sampling of coolant fragments was carried out in accordance with the recommendations (protocol) of the OLGA-system [6]: three biopsy samples from the antrum (greater and lesser curvature, angle of the stomach) and two biopsy samples from the body of the stomach (anterior and posterior walls). After standard procedures of material transfer and paraffin embedding, histological sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. To identify H. pylori, staining with 0.1% toluidine blue was used; Alcian blue (pH = 2.5) was used in combination with the PAS reaction to identify foci of intestinal and pseudopyloric metaplasia. When examining the biopsy material, moderate mononuclear inflammatory infiltration and signs of moderate gland atrophy were found both in the antrum and in the body of the stomach.

At the same time, the presence of non-metaplastic atrophy was noted in the antrum, characterized by shortening of the gastric (pyloric) glands with signs of fibrosis of the lamina propria. In the body of the stomach, a quantitative deficiency of glands was combined with signs of metaplastic atrophy, clearly visible using additional histochemical stains (Fig. 4): the original fundic glands were focally replaced by mucus-producing columnar epithelium, reminiscent of pyloric glands (pseudopyloric metaplasia), as well as intestinal epithelium with the presence of goblet cells. cells and brush border (complete intestinal metaplasia, type I). Colonization of H. pylori was not detected by histobacterioscopy. In the duodenal fragment there is preserved histoarchitecture, moderate lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lamina propria with an admixture of eosinophilic leukocytes.

According to the OLGA-system criteria, the morphological signs of chronic gastritis corresponded to grade III, stage III.

From the life history it is known that the patient was born in the Omsk region as a full-term, healthy child and works. Denies tuberculosis, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases. There were no injuries or operations. Denies blood transfusions. Allergy and hereditary history are not burdened. Concomitant diseases include autoimmune thyroiditis, euthyroidism (levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone, free T3 and T4 are normal).

Upon examination, the patient’s condition is satisfactory, her consciousness is clear, her physique is correct, her constitution is mixed, her nutrition is sufficient. Height – 166 cm, weight – 70.0 kg, body mass index – 25.4 kg/m2. The skin is pale pink and dry. Visible mucous membranes are pale and clean. The pharynx is pale pink, clean, the tonsils are not enlarged. Lymph nodes are not palpable. Thyroid gland grade 0 according to WHO. The joints are not deformed, there are no restrictions on active and passive movements. The spine is curved (scoliosis), painless on palpation. The chest is symmetrical, irregular in shape, scoliotic. Percussion above the lungs is a clear pulmonary sound. Breathing is vesicular, no wheezing. The boundaries of the heart are normal. Heart sounds are rhythmic, muffled, 70 per minute. Blood pressure 130/70 mmHg.

The tongue is moist, covered with a thick white-yellow coating at the root. The abdomen on superficial palpation is soft and painless. On deep palpation there is pain in the epigastrium, in the projection of the antrum of the stomach. Symptoms of peritoneal tension are negative. Symptoms of the gallbladder: Kehr, Ortner - negative, Murphy - weakly positive. The liver is not enlarged, the edge is smooth, elastic, painless. The pancreas is painless on palpation according to Groth. The spleen is not palpable. The kidneys are not palpable. The effleurage symptom is negative on both sides. There is no swelling.

Thus, we observe in a patient with epigastric pain syndrome atrophic changes in the mucous membrane of the antrum and body of the stomach with greater severity of morphological changes in the body, a combination of various forms of atrophy (absolute in the antrum and metaplastic in the body). Endoscopic and morphological studies carried out twice tell us that there is no H. pylori infection, which led to a search for other reasons for the formation of such changes. And of course, based on the data on the presence of atrophy of the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach, we considered the possibility of an autoimmune nature of the disease.

Discussion

Atrophic AIH was first reported by Thomas Addison, who in 1849 described a “prominent form of anemia,” later called pernicious. In 1860, Flint associated it with the development of coolant atrophy. Successful treatment with raw liver suggested that megaloblastic anemia was caused by a deficiency of extrinsic (vitamin B12) and intrinsic Castle factors in gastric juice. The discovery of antibodies to intrinsic factor by Schwartz in 1960 and antibodies to parietal cells by Irwin in 1962 substantiated the immunological nature of atrophic gastritis, leading to pernicious anemia [7, 8]. AIH was described in 1965 by OR McClntyre et al. in patients with pernicious anemia in whom histamine-resistant achlorhydria, coolant atrophy and antibodies to intrinsic Castle factor were detected [9].

The prevalence of AIH in the population ranges from 1 to 5%, according to some data – up to 15%, but large-scale epidemiological studies on this disease have not yet been conducted [10–12]. It has been indicated that the occurrence of AIH is associated with the population of Northern Europe, but recent studies do not support such ethnic clustering due to the lack of epidemiological data. However, all researchers agree on the frequent occurrence of AIH in females of the older age group, as in our clinical example.

Clinical manifestations of AIH can be presented in the form of gastroenterological, hematological and neurological syndromes, which is caused by progressive atrophy of the coolant with a gradual decline in active gastric secretion and the production of Castle factor, necessary for the absorption of vitamin B12. The course of the disease may be asymptomatic. Gastroenterological syndrome is characterized by symptoms of gastric dyspepsia: heaviness in the epigastric region that occurs during or shortly after eating, as well as decreased appetite, belching (empty, bitter taste, with an unpleasant odor), rarely - nausea and vomiting, which brings relief [13].

Patients with advanced AIH may experience iron deficiency anemia with typical manifestations such as weakness, dizziness, and sideropenic symptoms. Hypochromic anemia (in 15% of patients) can be caused by achlorhydria, because hydrochloric acid is important for the absorption of non-heme iron, which constitutes two-thirds of the required daily amount of iron in individuals following a “Western diet” [14]. Due to the increased need for iron at a young age and in sexually mature women, its deficiency may precede that of cobalamin for many years - until the loss of intrinsic factor becomes critical for those patients who develop typical pernicious anemia, in some cases accompanied by gastroenterological symptoms (gastric erosion) and funicular myelosis.

The absence of pathognomonic clinical signs of AIH justifies the importance of assessing endoscopic and morphological changes in the coolant in the body and antrum. The gastric mucosa demonstrates changes from minimal inflammatory to severe atrophy, maximally manifested in the body of the stomach, with pseudopolyposis and/or polyposis growths, which is associated with the alternation of atrophic areas of the gastric mucosa and hypertrophied areas of parietal and G-cells, activated under conditions of decreased secretion of hydrochloric acid.

During gastroscopy, the coolant is thinned, pale with a grayish tint, the folds of the mucous membrane are longitudinal, tortuous, the vessels of the submucosal layer are visible, polyps (hyperplastic, adenomatous, etc.) can be detected [15, 16].

When examining biopsy material in the early stages, multifocal lymphoplasmacytic infiltration with penetration into the deeper glandular part is observed in the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach. The glands may be destroyed in fragments, and the parietal cells may undergo pseudohypertrophic changes. Because these changes are nonspecific, pathologists may misinterpret results without information about serum markers. Metaplasia, chronic inflammation of all layers of the stomach wall and complete destruction of the glands are identified as early nonspecific changes in AIH. In addition, endocrine cell hyperplasia may be an early finding in AIH.

In our clinical case, to detect hyperplasia of neuroendocrine cells, we used the immunohistochemical detection method with antibodies to chromogranin A (clone SP12, Spring, USA) and the biotin-free UnoVue detection system (Diagnostic BioSystems, USA); primary high-temperature unmasking of the antigen in histological sections was carried out in a water bath in citrate buffer (pH=6.0) for 30 minutes. When reacting with chromogranin A, signs of hyperplasia of neuroendocrine ECL cells were determined in the body of the stomach (Fig. 5), determined by the criterion of the presence of small clusters of ≥5 positively stained cells arranged in a chain [17].

As the disease progresses, diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltration of the lamina propria of the coolant is detected with areas of pronounced gland atrophy, and intestinal metaplasia is clearly manifested. The final stage of the disease is characterized by a decrease or complete loss of the glands of the gastric body; moreover, pseudopolyps or hyperplastic polyps can be found, and inflammatory infiltration is reduced compared to earlier stages of the disease [18, 19]. Noteworthy is the fact that the above-described changes in AIH are maximally manifested in the body of the stomach compared to the antrum, therefore, biopsy samples should be taken according to the OLGA standard, as was done in the presented clinical case.

The issue of the effectiveness of using gastric pH-metry in the diagnosis of AIH is being discussed, but this method cannot reflect the full volume of gastric secretion and is a technically difficult and invasive procedure for the patient [120], which limits its use in this clinical situation.

An equally important element in the diagnosis of AIH is a serological study: determination of an increase in the serum amount of IgG antibodies to parietal cells, IgG antibodies to H+/K+-ATPase (adenosine triphosphatase of the proton pump) in the parietal cell, which is clinically accompanied by moderate or severe secretory insufficiency , as well as IgG antibodies to the internal Castle factor, which is clinically manifested by hyperchromic B12-deficiency anemia, hypopepsinogenemia-1 and hypergastrinemia resulting in functional hyperplasia of antral G-cells. Antibodies to intrinsic factor have demonstrated low sensitivity in studies [21], but their increase has been noted with disease progression [22]. It is worth paying attention to the fact that vitamin B12 levels do not correlate with antibody titers to Castle factor [23]. The level of antibodies to parietal cells is characterized by high specificity, but does not correlate with the severity of the disease, which is natural due to the progressive atrophy of the gastric glands in AIH [24], but these specific autoantibodies can precede clinical symptoms for a long time, as demonstrated in a number of other autoimmune disorders [25]. Gastrin and pepsinogen levels are not specific for the diagnosis of AIH, but predict the level of atrophy. In general, the determination of antibodies to gastric parietal cells is considered the optimal screening test for AIH, and the determination of antibodies to intrinsic factor is a backup technique for confirming the diagnosis. Antibodies to H. pylori are often detected, but the role of this infection in the development of AIH is controversial: the participation of H. pylori in the development of GM atrophy is explained by the phenomenon of antigenic mimicry [26, 27], as demonstrated in Fig. 6.

The role of ghrelin as a marker of the severity of atrophy of the gastric mucosa of patients with AIH is discussed [28]. The authors explain this relationship by the anatomical features of the close location of ghrelin-immunoreactive cells in the coolant and parietal cells, which become target cells during autoimmune damage. The researchers found that ghrelin levels negatively correlate with the severity of atrophic changes and can predict them with higher sensitivity and specificity compared to gastrin and pepsinogen.

The relationship between AIH and other autoimmune diseases is known, which requires a more thorough examination of such patients. There is evidence of its frequent association with type 1 diabetes mellitus. AIH can also coexist with polyglandular autoimmune syndromes, but its most common association is with autoimmune thyroiditis (“thyreostatic autoimmunity”): more than 50% of patients suffering from AIH have circulating antithyroid peroxidase antibodies [29], as in the case of our patient. Significant associations of AIH with vitiligo, alopecia, celiac disease, myasthenia gravis and autoimmune hepatitis have been reported [30, 31].

Taking into account the available data from endoscopic and morphological studies, the history of autoimmune thyroiditis in our patient, we conducted an additional examination to clarify the causes of the identified changes: according to the results of a general blood test - without pathology; biochemical blood test - an increase in triglyceride levels to 1.94 mmol/l was detected; coprogram - without pathology; cyanocobalamin, serum iron, total serum iron-binding capacity, transferrin, ferritin are normal, antibodies of the IgG and IgM classes to opisthorchiasis, giardiasis, toxocariasis were not detected; helminthological examination of stool using a complex ultrasensitive method - no helminth eggs were detected. According to the results of an abdominal ultrasound examination, there were diffuse changes in the pancreas. The patient also underwent a study of antibodies in the blood serum to Castle factor and parietal cells: antibodies to intrinsic Castle factor - 40.1 U/ml with a norm of 0-6 U/ml, antibodies to gastric parietal cells - titer 1:85 with a norm of up to 1:40. Thus, the patient was given a final diagnosis of “gastroesophageal reflux disease, non-erosive form, uncomplicated course. Cardia failure. Chronic atrophic H. pylori negative, autoimmune gastritis. Duodenitis. History of duodenal ulcer: cicatricial deformation of the duodenal bulb.”

Patients with AIH have a higher risk of developing cancer in chronically inflamed gastric tissue, according to the Correa cascade (1988). A meta-analysis from 2012 demonstrates that the annual incidence of gastric adenocarcinoma is 0.27% per person-year with an overall relative risk of 6.8% [32]. In addition, chronic achlorhydria increases the production of gastrin by G cells in the antrum, which then stimulates enterochromaffin cells, leading to their hyperplasia and the development of gastric carcinoids [33, 34]. Available data indicate the need for surveillance and treatment of AIH.

There are no standards for the management of patients with this disease. Taking into account changes in the coolant fluid in AIH (atrophy, intestinal metaplasia), domestic consensus documents recommend dynamic endoscopic observation, but, unfortunately, without indicating the frequency. We can find more detailed information in the Guidelines for the Management of Precancerous Conditions and Lesions in the Stomach (MAPS) [35]. When choosing a research method for diagnosing and monitoring patients with such changes, one should prefer magnifying chromo- and narrow-spectrum endoscopy (both with and without magnification). For adequate diagnosis of precancerous changes, it is necessary to perform at least 4 non-targeted biopsies from two topographic zones (body, antrum) and take targeted biopsy material from visually changed areas, and to assess the risk of developing gastric cancer, modern diagnostic systems for histopathological staging of the pathology under study (OLGA) should be used ). Patients with low-grade dysplasia and no endoscopic lesions may undergo another endoscopy after one year. In the presence of endoscopic lesions, endoscopic resection with careful morphological examination is desirable. If dysplasia is high and there are no endoscopic lesions, endoscopy should be immediately repeated with extensive biopsies and close follow-up for 6 months to 1 year. Taking into account the presence of intestinal metaplasia in our clinical case, we recommended that the patient undergo endoscopic monitoring after a year using chromoendoscopy and taking gastrobiopsy samples according to the OLGA standard.

Etiopathogenetic therapy for AIH has not been developed. The standard replacement treatment is regular monthly injections of vitamin B12 at a dose of 100 mcg to correct its deficiency. The most common maintenance regimen is vitamin B12 injections of 1000 mcg every 3 months [13]. The classic treatment regimen involves daily intramuscular injections of vitamin B12 at a dose of 100 mcg for 1 week, followed by monthly administration of 100 mcg. In severe cases, parenteral administration of 1000 mcg per day for 1 week is indicated, followed by 1000 mcg per week for 1 month, then monthly intramuscular injections of 1000 mcg.

It has been proven that in this category of patients, eradication therapy is associated with a decrease in the activity and severity of gastritis and in 80% of cases ensures the absence of progression of coolant atrophy when observed for 2 years. Thus, eradication in patients with AIH in the presence of H. pylori is an important aspect of the treatment of this disease [36, 37]. In the initial and progressive stages of the disease with preserved secretory function of the stomach, with serious disruption of immune processes, glucocorticosteroids are prescribed (short courses, average doses not exceeding 30 mg of prednisolone per day, subject to immune tests). The lack of effect makes a repeated course of such therapy impractical.

In addition, the treatment regimen for AIH should include treatment of dyspeptic syndrome with the use of antisecretory drugs and prokinetics at the onset of the disease. The treatment complex also includes enveloping drugs, and when secretory insufficiency develops, replacement therapy is used [38].

Considering AIH from the perspective of atrophic gastritis, we can recommend drugs that stimulate the production of hydrochloric acid in progressive stages. Currently, there are a lot of drugs that “theoretically” should have a stimulating effect on parietal cells. However, in real clinical practice, the effectiveness of most of them is very insignificant, and the duration of action is short.

It is still worth mentioning some methods of stimulating therapy:

- mineral waters (Essentuki No. 4, No. 17, Narzan, Mirgorodskaya) are used warm 15–20 minutes before meals;

- rosehip decoction, as well as lemon, cabbage, tomato juices diluted with boiled water;

- medicinal preparations (plantain, St. John's wort, wormwood, thyme). Particularly widely used in practice is Plantaglucide - granules of plantain leaves, which is used 1 teaspoon 3 times a day with warm water 20 minutes before meals;

- Limontar (citric and succinic acid) 1 tablet 3 times a day 20 minutes before meals [39].

It is advisable to consider mucocytoprotectors as a means of treatment for AIH, which improve trophism and regeneration of the coolant, and also, possibly, reduce the risk of carcinogenesis. Such drugs include bismuth tripotassium dicitrate and rebamipide [40].

Data on the use of proton pump inhibitors in AIH from the standpoint of their effect on coolant atrophy are controversial and ambiguous [41, 42]. In this matter, it is probably necessary to take an individual approach to the relationship between the causes of damage to the coolant and the occurrence of atrophy, taking into account the progression of the disease and prognosis.

In our clinical case, we recommended long-term administration of pantoprazole 40 mg 30 minutes before breakfast, alternating courses of mucocytoprotectors (bismuth tripotassium dicitrate 120 mg 4 times a day 30 minutes before meals and rebamipide 100 mg 3 times a day for 4 weeks) with taking Plantoglucid 1 teaspoon 3 times a day with 100 ml of warm water 15 minutes before meals for 4 weeks with subsequent observation: performing endoscopy with magnifying chromoendoscopy and taking biopsy samples, according to the OLGA-system protocol, in combination with targeted taking biopsies of the changed Coolant after 6 months.

Conclusion

Thus, in each specific case of chronic gastritis, it is important to assess the causative factor of damage to the coolant, as well as the degree, type, and prevalence of morphological changes in the mucous membrane (body, antrum of the stomach), which requires not only taking into account anamnestic data and the results of a physical examination, but also part of a competent analysis of the results of endoscopic and morphological studies. The close relationship between the clinician and the morphologist in matters of differential diagnosis of chronic gastritis is the key to the correct diagnosis and choice of patient management tactics.

Stomach - structure

The stomach consists of 4 functional sections: cardia, fundus, body and antrum.

- the cardiac section is responsible for controlling the flow of food from the esophagus into the stomach (and the esophageal sphincter prevents it from flowing back into the esophagus);

- the body and fundus of the stomach have a great ability to stretch (ingesting a large volume of food);

- the antrum has a thicker muscle wall (grinding and homogenization of the food mass before entering the intestine);

- The pyloric sphincter controls the flow of chyme into the intestines.

The histological structure of the stomach corresponds to that of any tubular organ (see diagram below). The gastric epithelium is secretory and produces both a protective buffer for the mucous membrane and digestive enzymes (the type of secretion depends on the location of the epithelium in the sections of the stomach).

Schematic diagram of the structure of a tubular organ, from the site https://www.vetmed.vt.edu

The author recommends this online resource as a real storehouse of educational information with very accessible explanations, drawings and microphotographs

Chronic atrophic gastritis: what the pathologist writes, what the clinician should understand and do

Vladimir Trofimovich Ivashkin , academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, Doctor of Medical Sciences:

– The time has come for Alexey Vladimirovich Kononov from Omsk to speak.

Alexey Vladimirovich Kononov , professor:

– Dear colleagues, today we will talk to you about the relationship between specialists in such a complex matter as cancer prevention and supervision of patients with precancerous conditions and precancerous changes. The central problem of cancer prevention is the problem of mucosal atrophy, which is a phenomenon located between the actual inflammatory changes in the gastric mucosa and precancerous changes, which Sergei Vladimirovich Kashin brilliantly demonstrated and called epithelial dysplasia. I prefer the term “neoplasia”, which emphasizes the irreversibility of these processes even in the form of a low degree of gradation of neoplasia. Thus, both the pathologist and the clinician have one question - this is the identification, detection of atrophy of the gastric mucosa and the interpretation of this conclusion.

What to do when the term “atrophy”, “atrophic gastritis” appears in the pathological report? Today there seem to be no problems with this. There is a main classification option for assessing mucosal atrophy - this is the modified Sydney system, where on a visual analogue scale these conditions are ranked into levels: no atrophy, weak, moderate, pronounced, both in the body and in the antrum of the stomach. But the problem is this. The problem is that for accurate identification of atrophy, even according to the modified Sydney system, not one fragment of the mucous membrane is needed, not two fragments, but 5 fragments taken according to the protocol: along the greater and lesser curvature of the body of the stomach, in the area of the angle of the stomach and along the greater and lesser curvature of the stomach lesser curvature in the antrum of the stomach. Moreover, when in 2008 we received a new classification of chronic gastritis, where atrophy and inflammation are assessed as integral concepts at the level of the whole organ, then taking a biopsy from 5 points is simply a necessary procedure, without which the system, which was called OLGIM, simply would not works.

This is a visual analog scale, a domestic version of it. According to the level of abscissas and ordinates of the pictogram, changes in the mucous membrane are weak, pronounced, moderate atrophy in the body, in the antrum, and at the crosshairs the stage, the severity of atrophic changes at the level of the whole organ. In the same way, a scale has been constructed to assess inflammatory changes, which are called the degree of gastritis, there are also pictograms there. Look, this is an inflammatory infiltrate, and here there are integrally neutrophilic leukocytes and mononuclear cells, which, in essence, represent the inflammatory response of the mucous membrane, and mucosal immunity at the same time. The problem is that there is a new understanding of mucosal atrophy. This is not just a reduction in the volume of glands in the body and antrum, but also their replacement with metaplastic epithelium. This is the so-called metaplastic atrophy, and this is its place in the Pelayo Correa cascade. Moreover, Pelayo Correa himself, by the way, has a very positive attitude towards this term and the identification of intestinal metaplasia with an assessment together with atrophy of the mucous membrane. The problem arises elsewhere. Sometimes the inflammatory infiltrate expands the gastric glands so much that the phenomenon of so-called indeterminate atrophy occurs.

Let's treat the patient, the inflammatory infiltrate will resolve partly as a result of apoptosis of inflammatory cells, partly as a result of migration through lymphatic vessels, interstitial spaces, and so on, and then we'll see. But if there is pronounced intestinal metaplasia, then it will not disappear anywhere. Maastricht-4 experts believe that metaplasia does not undergo reverse development, so the understanding of intestinal metaplasia has acquired some kind of mystical direction. In addition, it is also developed by type - complete, incomplete metaplasia, small intestinal, large intestinal, type IIA, IIB and so on. All this leads to thoughts appearing: isn’t intestinal metaplasia itself a precursor, a precursor to intestinal-type stomach cancer? Well, mountains of articles have been written on this subject and numerous spears have been broken; today it all comes down to the Cochrane review from September last year. There is no evidence-based research, completely built according to the criteria of evidence-based medicine, that intestinal metaplasia is a precancer, so let's listen to the personal opinion of David Graham, who, as always, expresses himself clearly, clearly and completely understandably: intestinal metaplasia today day is a reliable indicator of mucosal atrophy. There is intestinal metaplasia, which means there is atrophy of the mucous membrane.

By the way, our Baltic colleagues published in the January issue of this year “The Virchow Archive” - a respected, authoritative pathological journal in Europe - an article where they compared intestinal metaplasia, taken as a detection of atrophy, and the OLGIM system. It turned out that the criterion of expert agreement was higher where intestinal metaplasia was used as a marker of atrophy. True, our colleagues delicately note, there are stages of atrophic gastritis when intestinal metaplasia alone is not enough to detect atrophy itself. What else is written about intestinal metaplasia and atrophy? It turns out that we can work very closely with endoscopic diagnostic doctors. We can talk about the level of severity of atrophic changes by determining the stage, and endoscopic diagnostic doctors determine the area of foci of intestinal metaplasia, as Sergei Vladimirovich brilliantly showed today, and this combination gives a more accurate prognosis of carcinogenesis in a particular patient. Neoplastic changes are, in fact, tumor changes when the epithelial cell has taken the tumor path. It all started with the Padua questions almost 20 years ago, it all ended with the Vienna classification of neoplasia of the digestive tract, well known to you, dear colleagues, which was built, probably, as a model for all subsequent pathoanatomical and paraclinical classifications.

Here on the left are the changes that the endoscopic diagnostics doctor and the pathologist find in their conclusion, and on the right is written what the clinician should do with the patient. Definitions have been defined of what neoplasia is, what low-grade neoplasia is, and what high-grade neoplasia is. We can just look at the next slides while I'm talking. Please, next, next slide. Unspecified neoplasia. Just like indeterminate atrophy and indeterminate neoplasia – either these are regenerative changes, or this is actually a tumor process. And here is an interesting work that was published last year in the American journal Clinical Pathologies, which calls on us to integrate these two concepts - mucosal atrophy and neoplastic changes. When we are able to integrate both of these concepts in our conclusions, we will be able to give an accurate forecast. I would like to emphasize that tumor changes in the cells of the gastric mucosa do not occur in the air, they occur against the background and in combination with atrophic changes in the mucous membrane in general.

What consolations are possible? Should I just watch? Should we only take biopsies and make a diagnosis? Today we know new molecular cellular targets that were discovered relatively recently for the well-known drug based on bismuth ions. Well, firstly, the antioxidant property of bismuth. Free radicals of neutrophil leukocytes, arising from an oxygen explosion in them, disrupt the DNA of stem cells of the gastric mucosa to the level of double-strand breaks. These double-strand breaks undergo repair, but mutations arise, the accumulation of which can result in carcinogenesis. Thus, bismuth preparations protect DNA in conditions of inflammatory infiltration of the mucous membrane and prevent the process of marginalization. This is secondary prevention. Again, the ionic effect of bismuth was superbly demonstrated in an attempt to create a new drug where bismuth would be part of a soluble compound, and its ionic activity would increase.

2 years ago, molecular biologists received the Nobel Prize for their study of serpentine receptors and G-proteins, which are regulatory pathways of the cell. It turns out that bismuth intervenes in them and triggers a proliferative stimulus in stem cells, and by carrying out eradication with the help of bismuth salts, we simultaneously solve the second problem - we mobilize and stimulate local stem cells in the gastric mucosa, and if we do not eliminate atrophy, then at least We prevent its reverse development. What else is new with regard to bismuth ions as pharmaceuticals? The following results appeared. This is a work that is still only known in preprint, January issue, it has not yet been published. What does the preprint say? Tissue culture and bismuth ions. It turns out that bismuth ions have a lesser degree of damage to the bacterial cell of Helicobacter pylori than metallic bismuth, which is deposited in the form of a monolayer, atomic bismuth, on carriers that interact with the bacterial cell. Nanotechnology and the antibacterial effect of bismuth preparations are new.

Let's discuss a clinical example. A 55-year-old patient with dyspeptic complaints underwent an endoscopic biopsy of the gastric mucosa. What did the pathologist receive and what did he write? "Two fragments of the mucous membrane - the body and the antrum." I want to draw your attention to two fragments. Next, the pathologist describes the situation using the classification scheme, modified Sydney system. Everything is very correct, in every bite, and it detects changes in the body and antrum of the stomach. What should the clinician do after receiving such a conclusion? Well, first of all, accept that Helicobacter-associated atrophic gastritis has been verified. Very good. Then he must note to himself that he must identify the stage according to the OLGA system and. Accordingly, the risk of stomach cancer is impossible. What else should the clinician think about? He should think that, of course, there is a risk of stomach cancer, especially if it is atrophy in a patient over 50 years of age, but the risk is not certain. Then he must definitely carry out eradication therapy, but when he performs a control endoscopic examination 4 weeks after the end of eradication therapy, then it is necessary, it is simply necessary to take 5 biopsies from the specified points exactly according to the protocol and determine the stage of atrophy according to the OLGA system. This is how it all looks ideally, and this is how it looks in the example just considered, and this is common practice.

Let's see what this looks like at the population level. Look, 20 thousand gastrobiopsy samples from 9 thousand patients, and only 4% of studies can be assessed from the perspective of determining the risk of stage 3, 4 gastric cancer according to the OLGA classification. Let's see what's happening in America. Robert Maximilian Genta, a famous gastroenterologist pathologist and WHO expert on tumors of the digestive tract, did exactly the same study that we did, only 20 times larger, there were 400 thousand biopsies. But he got the same percentage: only 4% is suitable for assessing the risk of stomach cancer according to the modern classification. Second clinical example. In a 45-year-old patient, an endoscopic examination verified a visible area of changes in the form of an area of 0.5x0.7 cm, from which a biopsy specimen was taken. What does the pathologist write? One biopsy. The pathologist writes: “The morphological signs of focal epithelial dysplasia/neoplasia, well, “dysplasia” and “nonplasia,” as we agreed, are synonymous terms, are low grade (tubular adenoma with low grade neoplasia).”

What should the clinician think about? Without talking to Sergei Vladimirovich, we discussed this situation, so I can only comment. Well, first of all, accept that the patient has a precancerous condition or even a precancerous disease. It should then be noted that the risk of developing stomach cancer cannot be determined. First, one fragment. A piece taken side by side may show high-grade dysplasia/neoplasia, and a third piece may show invasive carcinoma. This means that the entire volume of the formation should be represented fairly representatively during repeated biopsies, if it is not possible to perform mucosal resection as written in the European recommendations for precancerous conditions. Well, and finally, what should a gastroenterologist or therapist do in this situation? He should at least order a repeat study in order to take biopsies from the visually changed area, as well as 5 biopsies according to the OLGA system in order to accurately determine the patient's risk of gastric cancer.

And one last example. A 55-year-old patient with chronic Helicobacter-associated gastritis, severe atrophy (stage III) - it should be noted that the risk of stomach cancer is a priori increased by 5-6 times compared to the population - successful eradication therapy was performed. An endoscopic examination 4 weeks after the end of therapy has the following result. 5 fragments were taken according to the scheme. These are the pictures that we look at through a microscope. This is plastic atrophy in the antrum, but what particularly excited us was that a month after the end of eradication therapy, neutrophilic leukocytes remained in the infiltrate in the lamina propria of the mucous membrane. And we have already agreed on what the oxygen explosion of neutrophil leukocytes is fraught with, and this is atrophic gastritis, by the way.

What should the clinician do in response to these comments made by the pathologist? How should he interpret this situation? Well, first of all, we must state successful eradication, but we cannot rest easy on this. He should note that the level of atrophic changes remained the same - which, in general, is not surprising - and this is a level that indicates the risk of stomach cancer is 5-6 times greater than in the population. Pay special attention to the infiltration of neutrophilic leukocytes, that is, inflammatory activity. This is a hidden threat of damage to the DNA of stem cells, especially atrophied mucous membranes, and the danger of carcinogenic mutations. What to do with the patient? And refer to the recommendations of the Russian Gastroenterological Association. And I want to end with the same recommendations that the dear Sergei Vladimirovich has already quoted. In case of chronic gastritis, including atrophic gastritis, after the end of eradication therapy, it is possible to continue treatment with bismuth for 4 to 8 weeks to ensure protection of the gastric mucosa. Thank you, dear colleagues!

Functions of the stomach

Gastric juice helps begin the digestion of proteins (pepsin) and fats (gastric lipase), and also stimulates gastric emptying and stimulation of the secretory function of the pancreas. In addition, gastric acid limits the proliferation of gastrointestinal microflora. It is noteworthy that gastric lipase remains active in the small intestine and accounts for up to 30% of total lipase in dogs.

The stomach is protected from gastric acid by the BSG - a barrier of the gastric mucosa. This concept includes a dense epithelial layer, secreted bicarbonate mucus, local production of prostaglandins and rapid repair of the epithelium in case of damage.

Causes of gastritis

- Use of medications (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - aspirin, diclofenac, etc.).

- Alcohol abuse.

- Smoking.

- Poor nutrition – too strict a diet or eating spicy, fatty, smoked and salty foods.

- Various stressful situations.

- Reverse flow of bile from the gallbladder into the duodenum and stomach.

- Severe diseases of the nervous system.

- Acute decrease in blood flow as a result of stress.

- Trauma, multiple fractures.

- Infectious diseases, including tuberculosis, HIV, syphilis, cytomegalovirus, parasitic infection.

- Radiation (radiation therapy).

- Allergic reactions.

- Autoimmune disorders and diseases.

- Crohn's disease.

- Other diseases of the gastrointestinal tract.

The vast majority of cases of chronic gastritis (85-90%) are associated with infection by Helicobacter pylori (Hp), a bacterium that lives under the parietal mucus of the stomach, on the surface of cells or in intercellular spaces. Helicobacter pylori can penetrate cells, causing them to become disorientated.

The spectrum of action of bacteria on the gastric mucosa is diverse:

- damage to the protective barrier of the gastric mucosa;

- death of gastric epithelial cells;

- immune reactions, as a result of which inflammation is maintained in the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum;

- increased production of hydrochloric acid;

- increased risk of developing ulcers and stomach cancer.

Microflora of the stomach

The stomachs of dogs and cats are constantly inhabited by Helicobacter spp. These are acid-tolerant microorganisms that produce urease to create a buffer that protects them from acid. Some other bacteria (Proteus, Streptococcus, etc.) may be temporarily present, but normally acid secretion and normal peristalsis successfully regulate their numbers. Therefore, with a decrease in the secretory function of the mucosa, proliferation of these microorganisms may be observed. The role of Helicobacter in the development of inflammation and mucosal atrophy in cats and dogs is debated.

The diagnosis of “gastritis” is one of the most common diagnoses made by veterinarians for animals whose owners complain of acute or chronic vomiting. Meanwhile, the syndrome of acute (chronic) vomiting is not always associated directly with the gastrointestinal tract, and stomach diseases are not only gastritis. In addition to inflammatory causes, stomach diseases can be associated with a number of others. In foreign literature, stomach diseases are usually divided according to their etiology and pathogenetic mechanism:

- inflammation (inflammation);

- infectious (invasive) causes (infection);

- diseases associated with obstruction;

- diseases associated with impaired motor skills (dysmotility);

- oncological diseases (neoplasia);

- erosive and ulcerative lesions (ulcer).

The article provides information on a group of diseases united by inflammation as the main pathogenetic mechanism of development.

Acute gastritis in dogs and cats

Acute gastritis is the term used to define the syndrome of sudden onset of vomiting. Most often, the cause of the condition can be determined by questioning the owner in detail. Damage to the gastric mucosa with subsequent inflammation can occur either through direct contact with a damaging substance (in this case we are talking about primary acute gastritis), or due to indirect damage associated with diseases of other organ systems (secondary gastritis, a striking example is uremic gastropathy in chronic renal failure).

| Cause | Examples |

| Feeding irregularities or food intolerances | Eating garbage; food allergy |

| Foreign bodies | Bones, toys, hairballs |

| Drugs and toxins | Antibiotics, NSAIDs, heavy metals, poisonous plants, household chemicals, bleach |

| Systemic diseases | Hyperadrenocorticism, uremia, liver disease |

| Parasites | Ollulanus, Physaloptera spp. |

| Bacteria | Bacterial toxins, Helicobacter? |

| Viruses |

What symptoms should you be wary of?

Symptoms of the disease vary slightly depending on the type of gastritis.

Thus, with exacerbation of chronic gastritis type A (autoimmune), flatulence, diarrhea, rumbling in the stomach, and loose stools after eating dairy products and fats are more common.

If we are talking about chronic gastritis type B (caused by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori), then in this case the disease is more often manifested by constipation or a tendency to it. In addition, the disease is characterized by heaviness in the epigastric region, which most often appears after eating, belching, nausea, regurgitation, unpleasant taste in the mouth (usually in the morning), and heartburn.

Pain in the stomach area is often dull and appears, as a rule, after eating (especially after eating spicy foods, fried, smoked foods). Gastritis pain intensifies when walking and standing.

The insidiousness of chronic gastritis is that it can be completely asymptomatic for a long time, sometimes for several years, or with minor pain in the abdominal area, which does not particularly bother patients. Most often, this disease occurs in adult men.

Clinical signs of acute gastritis in dogs and cats

The main clinical sign is sudden onset of vomiting. It is important to remember that sometimes anorexia may be the only clinical sign (as a consequence of nausea) in acute gastritis. The general condition of the animal is most often satisfactory; there may be a decrease in appetite and activity. If acute gastritis is associated with the ingestion of foreign bodies, toxins, systemic disorders, there is often an admixture of blood in the vomit, feces, concomitant diarrhea, and a significant deterioration in the general condition. Such patients require a more thorough diagnostic approach.

Diagnosis of acute gastritis in dogs and cats

Based on anamnestic data, clinical manifestations and response to symptomatic treatment. If there is no evidence of systemic disease, diagnostic testing is usually not necessary. However, it is necessary to begin the examination immediately if:

- there are signs of a systemic disease;

- there is a significant deterioration in general condition;

- in addition to vomiting, there is diarrhea, abdominal pain, blood in the vomit and/or stool;

- fever is present;

- history of ingestion of foreign objects, toxic substances;

- no response to symptomatic therapy within 1-2 days.

The basic diagnostic profile in these situations includes:

- general clinical and biochemical blood test, stool test for parasites (flotation method), urine test;

- X-ray examination (with and/or without contrast);

- Ultrasound;

- endoscopy.

Additional studies may be included in the examination protocol based on the results of basic tests (PCR for infections, bile acid test, test for specific pancreatic lipase, etc.)

Feeding cats and dogs with acute gastritis

It is advisable to provide “rest” to an inflamed stomach. Its duration depends on the age of the animal and the severity of gastritis. The fasting diet should not be too long, since the flow of food into the gastrointestinal tract maintains its barrier function. Usually for uncomplicated gastritis it is 12-24 hours. The inflamed mucous membrane reacts to stretching, so to avoid resumption of vomiting, portions of water and food should be as small as possible. The main goals are to avoid stretching the stomach walls and minimally stimulate acid secretion. It is known that among protein sources, the most active secretion stimulator is animal protein, and vegetable and milk proteins stimulate acid production the least. Therefore, when choosing a diet for a patient who is on a natural diet, it is worth choosing low-fat cottage cheese and rice in a ratio of 1:3. Of the ready-made diets, the best ones are those containing soy hydrolysate as the only source of protein (for example, PRO PLAN® VETERINARY DIETS HA), or easily digestible therapeutic diets with a low protein content for animals with diseases of the gastrointestinal tract (for example, Purina® EN).

Complications of gastritis

An ulcer (peptic ulcer) of the stomach is a severe, deep inflammation of the mucous membrane, which affects not only the superficial, but also the muscle tissue. An ulcer is a focal lesion of the mucous membrane, which is corroded by gastric acid. It is impossible to completely cure a stomach ulcer; you can only achieve long-term scarring of the ulcer by strictly following the recommendations of your doctor.

The symptoms of an ulcer are very characteristic: sharp cutting pain on an empty stomach, heartburn, vomiting. In some cases, an ulcer can put you at risk for developing stomach cancer.

Stomach cancer can develop quite slowly, over many years, and is rarely accompanied by pronounced clinical symptoms, so the patient, as a rule, is not even aware of his disease. The causes of the development of stomach cancer are called both polyps - mushroom-shaped formations growing from the mucous membrane, and Helicobacter pylori infection - damage to the gastric mucosa by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori.

Most gastric tumors arise in the glands of the mucous membrane - adenocarcinoma. However, other tumors, for example, lymphomas, develop from lymphoid nodes located in the walls of the stomach, stromal tumors - from muscle or connective tissue, etc.

Gastritis is fertile ground not only for the development of gastrointestinal diseases. Digestive disorders affect the condition of the body as a whole, since in this case the functional systems do not receive the substances necessary to ensure normal functioning. Also, complications of gastritis are clearly expressed symptoms - flatulence (increased gas production), diarrhea, constipation.

Treatment with gastroprotectors for cats and dogs with acute gastritis

Drugs in this group are prescribed for gastritis to protect the gastric mucosa, as well as to bind bacterial toxins and the bacteria themselves. The drugs of choice are:

- sucralfate (dogs - 1 g/30kg every 8-12 hours, 30-60 minutes before feeding, cats - 250 mg/cat); You can prepare a suspension from the tablet form and drink it, this is considered more effective;

- Bismuth preparations: have a cytoprotective effect and are also active against Helicobacter bacteria. Long-term use should be avoided due to possible adsorption of bismuth salts.

H2-blockers and antibiotics: it is advisable to prescribe them in case of signs of erosive damage to the gastric mucosa (hematemesis, melena), as well as in chronic gastritis. For acute uncomplicated gastritis, they are usually not necessary.

What is the prevention of gastritis?

Prevention of gastritis consists of maintaining a healthy lifestyle, proper and regular nutrition, quitting smoking and alcohol abuse. Of course, it is necessary to undergo an annual examination by a therapist, standard blood tests, and, if necessary, esophagogastroscopy (examination of the gastric mucosa using a gastroscope).

If you still have questions, you can ask them to a gastroenterologist online in the Doctis application.

Antiemetic treatment of cats and dogs with acute gastritis

The prescription of antiemetic drugs for acute gastritis is justified only in cases where intense repeated vomiting leads to significant dehydration and significantly worsens the animal’s condition. In other cases, it is worth trying not to prescribe antiemetic drugs in order to assess the response to symptomatic treatment (diet therapy + gastroprotectors). If vomiting continues, antiemetics are included in the treatment protocol and the diagnostic plan is revised. Drugs of choice:

- maropitant - 0.1 ml/kg once a day; in addition to a powerful antiemetic effect, it significantly reduces abdominal discomfort, which can significantly improve the patient’s general condition in a short time.

- metoclopramide - 0.2-0.5 mg/kg every 8-12 hours; The antiemetic effect is weaker than that of maropitant, but its prokinetic effect suppresses gastroesophageal reflux and promotes gastric emptying.

Chronic gastritis in dogs and cats

This is a fairly common disease in dogs (found on average in 30-35% of dogs examined both for chronic vomiting and for other reasons; characteristic symptoms may not be expressed); There are no reliable studies on the incidence of chronic gastritis in cats. Important aspects:

- chronic gastritis is a histological diagnosis, that is, it can only be confirmed by histological examination of gastric biopsies;

- all possible causes of chronic vomiting and other gastrointestinal diseases in dogs must be excluded before a diagnosis of chronic gastritis can be made;

- If the diagnosis of chronic gastritis is confirmed histologically, it is necessary to try to find its cause before recognizing it as idiopathic. Most often, the cause can be identified.

Principles of diagnosis and rational pharmacotherapy of chronic gastritis

Maev I.V., Golubev N.N.

At the present stage of development of gastroenterology, the term “chronic gastritis”; unites a whole group of diseases characterized by inflammation of the gastric mucosa.

The main cause of chronic gastritis is H. pylori infection. Only less than 10% of cases occur due to autoimmune gastritis, rare forms of gastritis (lymphocytic, eosinophilic, granulomatous), other infectious agents and chemicals. The prevalence of chronic gastritis in the world population is very high and ranges from 50 to 80%. In Russia this figure is at the same level.

Classification of chronic gastritis: The modified Sydney classification involves the division of chronic gastritis according to the etiology and topography of morphological changes. There are three types of gastritis [24]:

- non-atrophic (superficial) gastritis;

- atrophic gastritis;

- special forms of chronic gastritis (lymphocytic, eosinophilic, granulomatous, chemical, radiation).

Non-atrophic antral gastritis and multifocal atrophic gastritis involving the body and antrum of the stomach are associated with H. pylori infection. Atrophic gastritis of the body of the stomach is of an autoimmune nature.

The basic principles of diagnosis and rational pharmacotherapy of chronic gastritis associated with H. pylori are discussed below.

Pathophysiology of chronic Helicobacter gastritis and the natural history of H. pylori infection

H. pylori infection is characterized by long-term persistence on the gastric mucosa with the development of infiltration of its lamina propria with inflammatory cells. Infection with H. pylori always leads to the development of an immune response, which almost never ends, however, in the complete elimination of the pathogen. This is primarily due to the fact that, unlike other extracellular pathogens, H. pylori causes a predominantly type 1 immune response, accompanied by activation of the cellular component of immunity [27,37].

The development of neutrophil infiltration of the lamina propria is associated with two different mechanisms. The direct mechanism is realized through the release of neutrophil-activating protein by H. pylori, and the indirect mechanism is through stimulation of the expression of IL-8 by epithelial cells, followed by the launch of a complex inflammatory cascade [37].

Granulocytes migrating into the gastric mucosa damage epithelial cells by releasing reactive oxygen species and intensively produce pro-inflammatory cytokines. Under such conditions, against the background of progression of inflammation, in some cases there is damage and death of epithelial cells with the formation of erosive and ulcerative defects, while in others atrophy, metaplasia and neoplasia of the gastric mucosa gradually form.

Another significant feature of the pathogenesis of H. pylori infection is the failure of humoral immunity and the lack of eradication under the influence of anti-Helicobacter antibodies. This fact is usually explained by the “inaccessibility” of the bacterium to antibodies in the layer of gastric mucus, the inability to release IgG into the lumen of the stomach with a relative deficiency of secretory IgA, as well as “antigenic mimicry” of the bacterium [37].

Despite the fact that chronic gastritis develops in all people infected with H. pylori, not every case has any clinical manifestations. In general, for H. pylori-positive patients, the lifetime risk of developing peptic ulcers and gastric cancer is 10–20 and 1–2%, respectively [27].

Duodenal ulcers (DU) and gastric cancer are commonly associated with different types of chronic gastritis. With antral gastritis with the absence or minimal severity of atrophy, normal or increased secretion of hydrochloric acid, duodenal ulcers often develop. In pangastritis with severe atrophy of the mucous membrane, hypo- or achlorhydria, gastric cancer is recorded much more often [15,25].

This fact was explained after the discovery of H. pylori, when it became clear that in most cases, antral gastritis and pangastritis represent different directions of the natural course of this infection.

After infection, which usually occurs in childhood or adolescence, H. pylori causes acute gastritis with nonspecific transient symptoms of dyspepsia (epigastric pain and heaviness, nausea, vomiting) and hypochlorhydria [17,27].

Subsequently, acute Helicobacter pylori gastritis becomes chronic. Either superficial antral gastritis or atrophic multifocal pangastritis gradually forms. The key factor determining the topography of gastritis, and therefore the likelihood of developing duodenal ulcer or gastric cancer, is the level of hydrochloric acid secretion [17,25,27].

In individuals with normal or high secretory activity of parietal cells, hydrochloric acid inhibits the growth of H. pylori in the body of the stomach, and the bacterium intensively colonizes only the antrum, causing, accordingly, limited antral gastritis. Chronic inflammation in the antrum leads to hypergastrinemia and hyperchlorhydria, acidification of the duodenal cavity and ulceration. In patients with reduced levels of hydrochloric acid secretion, H. pylori freely colonizes the mucous membrane of the gastric body, causing pangastritis. Chronic active inflammation, through the effects of a number of cytokines, further inhibits the function of parietal cells, and subsequently causes the development of atrophy and metaplasia of the main glands. As a result, this category of patients has a significantly increased risk of developing stomach cancer [17,25,27].

According to modern concepts, the decisive role in the determination of these processes belongs to the genetic factors of the human body. They are directly related to the characteristics of the immune response, in particular, the level of production of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-1β, which has pronounced antisecretory properties. Genetically determined overexpression of this substance causes persistent suppression of hydrochloric acid secretion already at the stage of acute Helicobacter gastritis. In this situation, favorable conditions are created for the colonization of H. pylori in the body of the stomach [14,15].

The close relationship between gastric cancer and H. pylori has also been confirmed by large epidemiological studies. The presence of infection increases the risk of developing this malignant tumor by 4-6 times. In patients with chronic atrophic pangastritis associated with H. pylori, the likelihood of neoplasia increases even more. The International Agency for Research on Cancer has classified H. pylori as a Class I human carcinogen for non-cardiac gastric cancer [6].

Thus, chronic Helicobacter gastritis is the background against which gastric cancer develops in most cases. An important condition for its occurrence is the presence of disturbances in cellular renewal in the gastric mucosa in the form of its atrophy and intestinal metaplasia.

Diagnosis of chronic gastritis

A reliable diagnosis of chronic gastritis can be established only after a morphological examination of biopsy samples of the gastric mucosa by a morphologist. To adequately assess histological changes and determine the topography of chronic gastritis in accordance with the requirements of the Sydney system, it is necessary to take at least five biopsies (2 from the antrum, 2 from the body and 1 from the angle of the stomach). The conclusion should contain information about the activity and severity of inflammation, the degree of atrophy and metaplasia, and the presence of H. pylori.

Non-invasive diagnosis of atrophic gastritis can be carried out using a number of serum markers. Severe atrophy of the mucous membrane of the gastric body is characterized by a decrease in the level of pepsinogen I, and atrophy of the antrum is manifested by low levels of basal and postprandial gastrin-17.

Determining antibodies to gastric parietal cells and identifying signs of B12-deficiency anemia helps to exclude autoimmune chronic gastritis.

The fundamental point in the diagnosis of chronic gastritis is the identification of H. pylori. In practice, the choice of a specific method in most cases is determined by the clinical characteristics of the patient and the availability of certain tests.

All methods for diagnosing H. pylori, depending on the need for endoscopic examination and collection of biopsy material, are divided into invasive and non-invasive. Initial anti-Helicobacter therapy can be prescribed if a positive result of any of them is obtained.

Chronic gastritis always requires morphological confirmation. In this case, preference should be given to invasive methods for diagnosing helicobacteriosis, which include a rapid urease test, histological examination of biopsy specimens of the gastric mucosa for the presence of H. pylori, and polymerase chain reaction in the biopsy specimen [31].

Primary diagnosis of helicobacteriosis using these tests can give false negative results when the density of bacterial contamination of the mucous membrane is low, which often occurs when taking proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), antibiotics and bismuth preparations, as well as with severe atrophic gastritis. In such cases, a mandatory combination of invasive methods with the determination of antibodies to H. pylori in blood serum is recommended [33].

Eradication monitoring, regardless of the tests used, should be carried out no earlier than 4-6 weeks after the end of the course of eradication therapy. Preference should be given to a urease breath test and determination of the H. pylori antigen in stool using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). If these non-invasive methods are not available, histological examination and rapid urease test should be repeated [31].

Treatment of chronic Helicobacter gastritis

Treatment of chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis involves eradication therapy, the goal of which is the complete destruction of H. pylori in the stomach and duodenum. The need for treatment of helicobacteriosis in such patients is associated with the prevention of non-cardiac gastric cancer and peptic ulcer, since most patients with gastritis do not present any complaints. Only eradication of H. pylori allows one to achieve regression of inflammatory phenomena, as well as prevent the development or progression of precancerous changes in the mucous membrane [22,31].

It should be noted that long-term monotherapy with PPIs for chronic Helicobacter gastritis is unacceptable. Persistent suppression of acid production promotes the movement of H. pylori from the antrum to the body of the stomach and the development of severe inflammation there. The prerequisites are created for changes in the topography of gastritis. Predominantly antral gastritis turns into pangastritis. In such patients, the likelihood of developing atrophy of the mucous membrane of the body of the stomach, essentially iatrogenic atrophic gastritis, increases [6,31].

In the recommendations of the III Maastricht Consensus, only atrophic gastritis appears among the absolute indications for prescribing anti-Helicobacter therapy. At the same time, the compilers of authoritative international guidelines emphasize that it is still optimal to carry out therapy before the development of atrophy and intestinal metaplasia of the mucous membrane, still at the stage of non-atrophic (superficial) gastritis. Eradication in close blood relatives of patients with gastric cancer is strongly recommended [15,21,31].

Modern anti-Helicobacter therapy is based on standard regimens based on PPIs and bismuth tripotassium dicitrate (De-Nol). The Third Maastricht Consensus recommendations for the treatment of H. pylori infection distinguish between first- and second-line treatment regimens. Options for third-line regimens (“rescue” therapy), which can be used after two unsuccessful eradication attempts, are being actively discussed [31].

Treatment begins with a triple first-line regimen: PPI at a standard dose 2 times a day, clarithromycin 500 mg 2 times a day and amoxicillin 1000 mg 2 times a day. It is recommended to extend the duration of therapy from 7 to 14 days, which significantly increases the effectiveness of eradication. The use of triple regimens including metronidazole is absolutely unjustified, since the critical threshold of H. pylori resistance to this antibiotic (40%) in Russia has long been overcome.

The prospects for first-line triple therapy are significantly limited by the rapid increase in Helicobacter pyloric resistance to clarithromycin.

The main reasons for the increase in the number of antibiotic-resistant strains of H. pylori are the increase in the number of patients receiving inadequate anti-Helicobacter therapy, low doses of antibiotics in eradication regimens, short courses of treatment, incorrect combination of drugs and uncontrolled independent use of antibacterial drugs by patients for other indications [5,31].

Multicenter studies to determine the resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin, conducted in countries of the European Region, revealed its presence in 21-28% of cases in adults and in 24% of cases in children [23,32]. The same unfavorable situation is gradually emerging in Russia. In 2006, in Moscow among adults and in St. Petersburg among children, resistant strains were detected in 19.3 and 28% of those examined [9,10]. By 2009, in St. Petersburg, their share in adult patients increased to 40-66% [2,4].

Increasing resistance of H. pylori to clarithromycin is leading to a steady decline in the effectiveness of standard first-line clarithromycin-based triple therapy. According to both Russian and foreign clinical studies, this figure is already 55-61% [3,30].

As an effective alternative to triple therapy, the Third Maastricht Consensus recommends a standard four-component regimen based on bismuth as the first line of eradication: bismuth tripotassium dicitrate (De-Nol) 120 mg 4 times a day, PPI at a standard dose 2 times a day, tetracycline 500 mg four times a day and metronidazole 500 mg 3 times a day for 10 days. It should be emphasized that the use of bismuth makes it possible to overcome the resistance of Helicobacter pyloricus to metronidazole [31].

This eradication option is preferable if there is a high level of H. pylori resistance to clarithromycin in the region (above 20%), if the patient has a history of allergic reactions to clarithromycin, amoxicillin or other antibiotics from their groups, as well as with previous use of macrolides for other indications.

In our country, a three-component regimen is used as first-line therapy with the inclusion of bismuth tripotassium dicitrate at a dose of 120 mg 4 times a day, amoxicillin at a dose of 1000 mg 2 times a day and clarithromycin at a dose of 500 mg 2 times a day. This combination is especially suitable for patients with chronic atrophic gastritis in the absence of any clinical symptoms. In such patients, there is no need for rapid suppression of hydrochloric acid production, and these regimens may be optimal in terms of cost/effectiveness ratio [6,14].

If, after triple anti-Helicobacter therapy of the first stage, treatment turned out to be ineffective (no eradication of H. pylori 6 weeks after complete withdrawal of antibiotics and antisecretory drugs), in accordance with the Maastricht recommendations, quadruple therapy based on bismuth tripotassium dicitrate is prescribed as a second-line regimen for a period of 10 days . Replacing metronidazole with furazolidone in this regimen does not reduce the effectiveness of treatment [35].

If quadruple therapy was used at the first stage, alternative second-line triple regimens can be used, including PPI at a standard dose and amoxicillin 1000 mg 2 times a day in combination with tetracycline (500 mg four times a day) or furazolidone (200 mg 2 times a day). times a day) [31].

In general, with the increasing resistance of H. pylori to the main antibacterial drugs, bismuth tripotassium dicitrate (De-Nol) begins to play a leading role in the first and second line eradication schemes, which is due to the presence of a number of unique properties.

Bismuth tripotassium dicitrate has the most pronounced antibacterial properties against H. pylori infection among all bismuth preparations. De-Nol is highly soluble in the aqueous environment of gastric juice and is able to maintain high activity at any level of gastric secretion. It easily penetrates the gastric pits and is captured by epithelial cells, which makes it possible to destroy bacteria located inside the cells. An important point is the complete absence of H. pylori strains resistant to bismuth salts [18,29].

The anti-Helicobacter effect of De-Nol is complex and is caused by a number of mechanisms [7,8,29]:

- precipitation on the membrane of H. pylori with subsequent disruption of its permeability and death of the microorganism;

- suppression of H. pylori adhesion to epithelial cells;

- suppression of H. pylori motility;

- effect on vegetative and coccal forms of H. pylori;

- synergism against H. pylori with other antibiotics (metronidazole, clarithromycin, tetracycline, furazolidone).

The latest data on the use of bismuth tripotassium dicitrate as an anti-Helicobacter therapy were obtained in a recent study aimed at assessing the effectiveness of a modified 7- and 14-day triple regimen in the first line. Tripotassium bismuth dicitrate was added to the standard combination, which included omeprazole, clarithromycin and amoxicillin, at a dose of 240 mg 2 times a day. Before starting treatment, the sensitivity of H. pylori to antibiotics was determined.

The results of the study showed extremely promising results. The 14-day treatment regimen demonstrated significantly greater effectiveness than the 7-day regimen. In the first case, eradication was achieved in 93.7% of patients, while in the second only in 80% of patients. In the presence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of H. pylori, treatment was successful in 84.6% of individuals who underwent a two-week course of treatment, and only in 36.3% of cases when using a 7-day regimen, which indicates the possibility of overcoming bacterial resistance to clarithromycin against the background use of bismuth preparation [34].

The indicated four-component regimen consisting of bismuth tripotassium dicitrate, PPI, amoxicillin and clarithromycin has already been recommended by leading Russian experts as one of the first-line treatment options for the treatment of helicobacteriosis [14].

Thus, the widespread use of bismuth tripotassium dicitrate provides in the future a real chance to compensate for the lack of new highly active antibacterial agents against H. pylori. A modified 14-day regimen containing this drug appears to be able to be used successfully as first-line therapy even in areas with a high prevalence of clarithromycin-resistant strains of the bacterium. This strategy will significantly reduce the level of resistance of Helicobacter pylorus to currently used antibiotics and maintain high rates of effectiveness of eradication therapy [28].

In addition to the antibacterial effect, bismuth tripotassium dicitrate has a pronounced cytoprotective effect. The drug creates a film on the surface of the mucous membrane of the stomach and duodenum that protects epithelial cells from the effects of the acid-peptic factor and potentiates repair processes in the area of erosive and ulcerative defects. Moreover, bismuth ions have the ability to directly stimulate the proliferation of epithelial cells [1,11,26].