Vomiting in cancer: treatment, causes

Vomiting in cancer occurs quite often and not without reason. Thus, during a course of chemotherapy, vomiting is a common result of using medications.

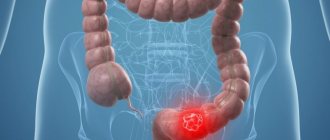

Vomiting is also observed with cancer of the liver. With brain cancer and gastrointestinal bleeding, vomiting also becomes one of the symptoms of the disease.

Causes of pathology

The human brain has a so-called vomiting center, which is responsible for the formation of the vomiting reaction, just like the chemoreceptor zone.

In a patient suffering from cancer, the central mechanism is activated simultaneously (impulses come from the cerebral cortex) and the peripheral mechanism (impulses come from the intestines, more precisely, its mucosa) or they appear separately from each other.

The central mechanism is triggered when:

- A surge in intracranial pressure in the area of brain damage;

- Increased levels of calcium in the blood;

- Intoxication caused by products produced by the cancer focus or its decay;

- As a result of a vomiting reaction caused by psychogenic factors.

The peripheral mechanism is activated when:

- Complications caused by toxic medications taken;

- The occurrence of intestinal obstruction or stenosis;

- Damage to a liver tumor.

Constant nausea is eliminated through increased doses of analgesic drugs, however, at the same time, gastrointestinal motility slows down.

Vomiting and progression of pathology

There is no single clear division into types of vomiting reaction, but, having examined the vomit, we can identify the following manifestations of pathology that occur after eating:

- Masses with altered blood - food has already been partially digested;

- Vomiting during or immediately after eating. Its cause is an increase in pressure inside the skull, psychomotor activity, and the development of a tumor in the esophagus.

- With toxins: atypical cells entering the liver, side effects of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, vomiting can occur constantly.

The contents of the vomit itself and its appearance may indicate the cause of the complication:

- With practically unchanged food residues, oncology of the esophagus or the transition connecting the esophagus and stomach is observed;

- A sour smell, if the contents are partially digested, indicates oncology of the stomach, namely its lower third;

- The presence of bile indicates a disease of the small intestine;

- The color of “coffee grounds” is a signal of gastric bleeding;

- A bitter odor along with yellow contents is characteristic of liver dysfunction.

What kind of vomiting occurs in such patients and what does it mean?

Depending on the consistency and color of the vomit, the degree of cancer development can be determined.

Vomiting without blood occurs when the affected tissues rupture, as well as when putrefactive processes develop in the affected organ. At the last stage, such vomiting appears regularly. In cases of cancer, the volumes of vomit are in most cases small, and they have a specific sour smell of decomposing tissue.

Vomiting blood is another phenomenon in advanced oncology, which indicates vascular damage. Blood can occur when a tumor is damaged, which has many vessels that support its growth. If the vomit is scarlet in color, this indicates extensive internal bleeding.

Black vomiting indicates hidden bleeding, which is no less dangerous for the patient’s condition. If transparent mucus appears in the masses, we are talking about a failure in gastric secretory function.

Light masses with bile impurities are direct evidence of blockage of the ducts, a consequence of the formation of metastases in the liver (such vomiting is characterized by frequent urges).

Vomiting in the last stage of cancer may occur immediately after eating (in this case, the bolus of food is pushed back by the body without gastric juice). Nausea can occur suddenly and regardless of food intake, this occurs when the tumor disintegrates.

Vomiting as a result of therapy

A constant feeling of nausea and vomiting negatively affects cancer therapy. Their presence makes the chosen treatment method less effective, since it is important for the doctor to monitor the general condition of the patient and adjust the course of his treatment.

The administered cytostatic during a chemotherapy session causes the patient's body to vomit. This happens over a number of days, even after using the drug. Sometimes it cannot be prevented with antiemetic medications.

All chemotherapy drugs have their own vomiting period; their prevention and treatment begin on the first day of treatment procedures and are completed a few days after their completion.

It is noteworthy that the bodies of men and women react differently to vomiting. So, in some women, after the first chemotherapy treatment, reflex vomiting may begin as a reaction to it. For men this is completely irrelevant.

During the application of radiation therapy, vomiting depends on two main factors - the area of \u200b\u200birradiation, the patient's readiness and internal readiness. Of course, age, gender and a number of other factors should be taken into account.

Nausea and vomiting in clinical practice (etiology, pathogenesis, prevention and treatment)

T

Nausea and vomiting are unpleasant subjective sensations that are familiar to almost every person.

They are caused by a variety of causes and involve complex physiological and biological mechanisms. Nausea and vomiting may be an early sign of illness, poisoning, or complications associated with surgery and anesthesia

. At the same time, vomiting can be a protective reflex act when a toxin enters the stomach with food masses. Doctors of all clinical specialties encounter the problem of nausea and vomiting, in adults and children, both in a hospital setting and in a clinic, in a one-day hospital, dental or cosmetology offices.

However, nausea and vomiting are more common as complications after surgery and anesthesia. In the era of mononarcosis with ether or chloroform, the incidence of postoperative vomiting reached 75–80% [4]. Often it was repeated, which raised fears of the development of fatal complications in the form of aspiration of vomit, dehiscence of anastomotic sutures, sutures of the anterior abdominal wall, eventeration, bleeding, increased intracranial pressure, cerebral edema, and complications after operations on the eyeball.

In recent years, new inhalational and non-inhalational anesthetics, new techniques of general and local anesthesia, and the incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) have decreased significantly and amount to 20–30% [1,2,3]. However, the problem of preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting is still far from being completely resolved.

At this stage of development of medical science, the doctor must know the basic pathophysiological mechanisms of nausea and vomiting, take measures to prevent and treat this complication, and create comfortable conditions for patients to recover.

Physiology of vomiting

Vomiting is a reflex act of forced eruption of stomach contents through the mouth, occurring against the background of pyloric spasm, relaxation of the fundus of the stomach and cardiac sphincter of the esophagus with simultaneous powerful jerky contraction of the abdominal muscles, lowering of the diaphragm and increased intra-abdominal pressure. Typically, vomiting is preceded by a pre-eruption phase, which consists of symptoms of vegetative and somatic components: nausea, the appearance of a lump in the throat, a painful sensation in the epigastrium, reflux from the duodenum into the stomach, salivation, the appearance of a pale “nasolabial triangle”, tachycardia, dilated pupils, sweating.

Gagging is characterized by rhythmic synchronous movements of the diaphragm, abdominal and external intercostal muscles, while the mouth and glottis remain closed. In the post-eruption phase, signs of autonomic and visceral reactions persist, which gradually subside and return the patient to a state of rest with or without residual nausea. In some cases, after vomiting, nausea stops.

Thus, the complex act of vomiting involves the coordinated work of a group of respiratory, gastrointestinal and abdominal muscles. This coordination is controlled by the vomiting center.

The center of vomiting is located in the lateral part of the reticular formation near the tractus solitarius. All afferent flows from the pharynx, gastrointestinal tract, mediastinum, from the optic thalamus, the vestibular apparatus of the VIII pair of cranial nerves and the trigger (starting) zone of chemoreceptors, which is located in the area postrema of the brain stem, are sent here (Fig. 1). This zone is surrounded by a rich network of capillaries with extensive perivascular spaces that do not have an effective blood-brain barrier, and the chemoreceptor trigger zone can be activated by chemical stimuli through both the blood and the cerebrospinal fluid. The vomiting center is also excited by direct pressure on it from a brain tumor or through the blood, for example, with subcutaneous administration of apomorphine, as well as with the accumulation of various metabolic products in the blood, with exo- and endotoxicosis and autointoxication (hyperazotemia, ketoacidosis, hypoxia, metabolic disorders, hypotension, etc.). Thus, irritations from various areas of the central nervous system can affect the vomiting center.

Rice. 1. Causes and neuroreflex pathways of vomiting

The vomiting center is also excited by afferent impulses emanating from the gastric mucosa through the sensitive nerve endings of the vagus nerve or from the receptor apparatus of the pharynx through the glossopharyngeal nerve. In addition, afferent impulses can arise from the vestibular apparatus through the nerve endings of the auditory nerve, especially with individual weakness of this apparatus in cases of motion sickness in transport.

It is known that the area postrema of the brain stem is rich in dopamine, opioid, and serotonin (5-HT3) receptors. The area of the nucleus tractus solitarius is rich in enkephalins, histamine and muscarinic receptors, which play an important role in the transmission of impulses to the vomiting center. Stimuli can originate in different areas of the central nervous system. However, the triggering factors for the development of nausea and vomiting are direct irritation of the chemoreceptors of the trigger zone area postrema, which, through efferent transmission mechanisms, implement the act of vomiting. Thus, it is easy to assume that the selective blockade of these receptors is a function of many known and currently used antiemetics.

Factors contributing to nausea and vomiting

Factors influencing the development of nausea and vomiting include some characteristics of the patient himself, the underlying or concomitant pathology, the nature of the surgical intervention or diagnostic procedure and its location, the pharmacological characteristics of medications, the type and nature of anesthesia.

Among the factors related to the patient himself, it is necessary to take into account age and gender

. Vomiting occurs more often in children, especially in the teenage age group (10–14 years), and the frequency of vomiting decreases with increasing age. It has been noted that the incidence of vomiting after surgery is lower in men than in women. However, it has been noted that the frequency of nausea and vomiting increases in women during the menstrual cycle.

It is also necessary to pay attention to the anamnestic data in patients suffering from motion sickness syndrome

. They apparently have a reduced sensitivity threshold for the receptors of the vestibular apparatus and retain the “habitual” reflex arc of the gag reflex.

Each doctor must also take into account the type of nervous system of the patient and the severity of his autonomic reactions.

. It is well known that excitable, labile and restless patients have a higher incidence of nausea and vomiting than calm and balanced patients. It has also been noted that in restless patients with higher levels of catecholamines and serotonin, aerophagia develops, which causes an increase in the air bubble in the stomach and leads to irritation of the receptor apparatus.

There is also a positive association between the incidence of nausea and vomiting and obesity

. This is due to a number of factors. One of them is an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, compression of the stomach, the development of reflux, esophagitis and incompetence of the esophageal sphincter. Other factors may be the conditions of the operation and anesthesia, the presence of concomitant diseases of the gallbladder, high position of the diaphragm, and breathing disorders in the immediate postoperative period.

It is also necessary to take into account the initial hypotension of the stomach

, which can be observed in pregnant women, starting from the 23rd week of pregnancy, due to hormonal changes (decrease in gastrin and progesterone production).

In addition, it is necessary to ascertain in patients the presence of gastrointestinal function disorders, heartburn, regurgitation, spastic pain, paresis and intestinal atony. The latter may be a consequence of the initial neuropathy (diabetes mellitus, hyperazotemia, cancer cachexia).

Factors associated with surgery

It is known that the frequency of nausea and vomiting largely depends on the nature and location of the surgical intervention. The highest incidence of vomiting is observed during endoscopic operations on the ovaries during egg transfer (54%), as well as after laparoscopy (35%), during operations on the middle ear and otoplasty, after operations on the muscles of the eyeball for strabismus [5]. Frequent cases of vomiting have been reported in urology (lithotripsy, endourological interventions on the bladder and urethra), and in abdominal surgery (cholecystectomy, gastric resection, pancreatic surgery). The cause of nausea and vomiting in these cases is afferent impulses from the area of surgical intervention to the trigger zone of the chemoreceptor apparatus area postrema with subsequent excitation of the vomiting center.

Factors associated with anesthesia

There was a direct relationship between the frequency of vomiting and the duration of surgery and anesthesia. Most drugs and anesthetics have a potential emetic effect, and with increasing duration of anesthesia, the total dose of sedatives and narcotics usually increases, and the possibility of their toxic effect on the very sensitive receptor apparatus of the trigger zone increases.

The direct relationship between the frequency of nausea, vomiting, skin itching, and urinary retention and the prescription of morphine is well known.

Vomiting often occurs when using nitrous oxide mask anesthesia. Vomiting often occurs after laparoscopic operations in the abdominal cavity performed using combined anesthesia with nitrous oxide [1,2,3]. The reasons for this lie in the toxic effect of nitrous oxide on the receptor apparatus of the vestibular zone, changes in pressure in the middle ear, stretching of the receptor apparatus of the stomach and intestines due to the diffusion of gas into the “third space”.

The combination of nitrous oxide and halothane (fluorothane) also does not reduce the incidence of vomiting in adults and children.

A high incidence of vomiting was noted from the use of “old” inhalation agents (ether, chloroform, cyclopropane, chloroethyl). However, the incidence of vomiting did not decrease with the use of new inhaled halogen agents (isoflurane, enflurane, desflurane, and sevoflurane). Everything that is created artificially is, to one degree or another, toxic to the neurons of the vomiting center. Intravenous anesthetics are no exception. It is known that the use of intravenous anesthetics did not reduce the frequency of vomiting. Vomiting can also occur after the use of etomidate, ketamine, barbiturates and is observed in 10–15% of cases [4,5].

A more favorable picture was observed when using propofol

, which shows signs of antiemetic action in adults and children. The frequency of vomiting does not increase when propofol is combined with nitrous oxide. In this regard, propofol is the drug of choice in outpatient anesthesiology, since it provides a quick recovery from anesthesia and the patient experiences comfortable awakening conditions.

A similar effect is caused by a new gas anesthetic - xenon.

. The recovery from xenon anesthesia is smooth, calm, without signs of nausea and vomiting. Xenon is chemically indifferent in the body and does not enter into any metabolic processes. Even long-term 6-hour endoscopic operations under xenon anesthesia were not accompanied by any discomfort to the patient.

Potent nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have proven themselves to be effective in outpatient practice. One of them is ketoralac

, which provides prevention of postoperative pain after outpatient interventions and is clearly a better alternative to narcotic analgesics.

(Mydocalm)

is optimal .

Many procedures are now performed using local anesthetics and intravenous sedatives, which have a significantly lower incidence of nausea and vomiting. However, the frequency of nausea and vomiting may depend on the nature of the surgical operation and manipulation.

It is known that the cause of postoperative vomiting is often visceral pain.

. Relief of pain often leads to elimination of nausea. However, after surgery, arterial hypotension and hypovolemia are possible, which cause dizziness, staggering, incoordination, especially when moving the body, when transferring the patient from the operating table or from a gurney to the bed, which causes nausea and vomiting, which are often mediated through the vagus nerve. In these cases, nausea and vomiting disappear with the correction of hypovolemia and hypotension, as well as with the use of vasopressors and atropine.

Treatment of nausea and vomiting

Each case of nausea and vomiting requires an individual approach. In some patients, postoperative vomiting stops after 2-3 vomiting attacks, followed by relief. It must be remembered that repeated vomiting is one of the symptoms of a complicated course of the operation.

, the possibility of which the surgeon should always think about. Eliminating vomiting with medications in this case will lead to a masked course of the disease and complicate diagnosis.

At the same time, the prevention and treatment of vomiting should be carried out in persons with a high emetic risk, in whose anamnesis there is information about the presence of sea or air sickness, about intolerance to anesthetic drugs and medicines from a home first aid kit; in women who are undergoing laparoscopic operations, urological manipulations in the form of impact lithotripsy, orchipexy, middle ear surgery, eye surgery for strabismus, tonsillectomy, and cerebellar surgery. A special category includes patients who have received radiation therapy or chemotherapy.

When determining an algorithm for the prevention and treatment of vomiting, it should be remembered that signals to the vomiting center come from different types of receptors. Among them, four play an important role: dopamine

(D2),

M-cholinergic

,

histamine

(H1),

serotonin

(5-HT3), but the degree of their specificity varies. In this regard, it is logical to assume that the choice of a pharmacological drug for the treatment of persistent vomiting or the prophylactic prescription of the drug should be based on the point of application and the pharmacodynamics of the prescribed drug, taking into account the possibility of developing side effects. Table 1 provides a list of drugs that have antiemetic effects. The table shows that the direction of action and the severity of the antiemetic effect of different drugs are not the same. The question arises about the possibility of a combined approach to the treatment of persistent vomiting, which can provide a pronounced antiemetic effect. However, unfavorable side effects of the drugs are also possible (lowering blood pressure, lethargy, extrapyramidal effects, respiratory depression, etc.). The degree of selectivity of the therapeutic effect when exposed to a certain type of receptor varies, which determines the varying severity of side effects.

Phenothiazines

The antiemetic effect of a large group of phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, triftazine, etaprazine, fluorophenazine) is quite well known. This property is explained by their ability to block dopamine receptors in the trigger zone. However, phenothiazines can cause significant sedation (lethargy, drowsiness, lethargy, orthostatic hypotension), which limits their use in complicated cases and in outpatient settings.

The antiemetic effect of a large group of phenothiazines (chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, triftazine, etaperazine, fluorophenazine) is quite well known. This property is explained by their ability to block dopamine receptors in the trigger zone. However, phenothiazines can cause significant sedation (lethargy, drowsiness, lethargy, orthostatic hypotension), which limits their use in complicated cases and in outpatient settings.

Of these drugs, thiethylperazine

. It does not have pronounced sedative activity and only weakly potentiates the effect of hypnotics and analgesics, and practically does not cause extrapyramidal disorders. At the same time, thiethylperazine has a strong selective antiemetic effect and is superior to chlorpromazine in this property. The drug is effective for vomiting of various origins, since its effect consists of a calming effect on the vomiting center and at the same time on the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the medulla oblongata, i.e. a more universal mechanism can be traced in its action.

To prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), the drug is administered intramuscularly 1 ml (6.5 mg) 30 minutes before the end of the operation. While using the drug, drowsiness and postural hypotension may occur.

Butyrophenones

This group includes such well-known neuroplegics as droperidol, haloperidol, and domperidone. Their antiemetic effect is due to the blockade of dopamine receptors and is often used in the practice of anesthesiologists for the prevention and treatment of nausea and vomiting in the postoperative period. However, their use is also not recommended in outpatient settings (except in certain cases).

Small doses of droperidol (10–20 mg/kg) are used to prevent PONV during laparoscopic abdominal surgery. The action of domperidone is based on increasing motility of the upper gastrointestinal tract and a direct blocking effect on trigger zone chemoreceptors. It practically does not cause dystonic side effects and is used to prevent PONV in a dose of 5–10 mg immediately after induction of anesthesia. However, it cannot be prescribed simultaneously with anticholinergics, which are often included in the premedication regimen, due to its antagonistic effect on peristalsis.

Antihistamines

Antihistamines (diphenhydramine, hydroxycin, promethazine) act on the vomiting center and vestibular apparatus and are used to prevent motion sickness in transport. At the same time, drugs of this class are used in ENT practice to prevent vomiting after middle ear surgery. Drugs in this group reduce the body’s response to histamine, reduce vascular permeability, have a sedative effect, inhibit nerve impulses in the autonomic ganglia, and have a central anticholinergic and anti-inflammatory effect. In this regard, they are used in the treatment of radiation sickness, sea and air sickness, vomiting during pregnancy, Meniere's syndrome, and have a sedative and hypnotic effect. With pronounced emetic phenomena, their effectiveness is often insufficient.

Anticholinergics

Anticholinergics (atropine, metacin, scopolamine) prevent or weaken the interaction of acetylcholine with cholinergic receptors. Since various types of cholinergic (muscarinic) receptors are found in the chemoreceptor trigger zone and the vomiting center, most anticholinergics can form the basis for the prevention of nausea and vomiting. The use of atropine or metacin as premedication reduces the incidence of PONV, even when using narcotic analgesics. The use of scopolamine effectively relieves motion sickness and reduces the frequency of vomiting after outpatient laparoscopy. One of the drugs containing scopolamine and histiamine is known as Aeron, which is widely used for motion sickness in transport, to relieve attacks in Meniere's disease. Metoclopramide

– is a specific blocker of dopamine (D2) and partially serotonin (5-HT3) receptors, having both central and peripheral antiemetic effects. The drug is well known to anesthesiologists and is used to prevent vomiting and regurgitation in patients at high risk of developing aspiration syndrome. Metoclopramide increases the tone of the esophageal sphincter, increases gastric and intestinal motility, and is effective for the prevention of vomiting that occurs during chemotherapy, as well as for the prevention of PONV, especially in those patients in whom narcotic analgesics (morphine, fentanyl) were used during anesthesia. It is used in gastroenterological practice for gastrointestinal dysfunction, as well as in the treatment of dyspepsia, repeated vomiting, hiccups in cardiac patients and vomiting in pregnant women. It has no effect on vomiting of vestibular origin. Used in a dose of 10–20 mg.

It should be remembered that after taking metoclopramide, as well as almost all drugs of the above groups (neuroplegics - phenothinazines and butyrophenones, antihistamines similar in structure, anticholinergics), muscle weakness develops and concentration is impaired, which makes it difficult to perform a wide range of responsible actions - from driving before using household electrical appliances, etc. When metoclopramide is used in large doses necessary to prevent vomiting during chemotherapy sessions, cases of dystonia and extrapyramidal disorders have been reported, especially in children.

Serotonin antagonists

Currently, four serotonin receptor antagonists have been synthesized: tropisetron, ondansetron (Emetron), granisetron, dolasetron. Drugs of this group are successfully used in abdominal surgery and chemotherapy [1,2,3,5]. The first two of these drugs are most widely used.

Emetron

– a potent, highly selective antagonist of serotonin 5-HT3 receptors in both the central and peripheral nervous systems. It is used to prevent postoperative nausea and vomiting and is prescribed in a dose of 4 mg IV at the stage of induction of anesthesia, or orally 16 mg (2 tablets) 1 hour before the start of general anesthesia. Indications are operations with a high risk of PONV, especially in abdominal surgery during endoscopic operations, in emergency surgery after operations on the abdominal organs. The drug is also prescribed during a chemotherapy session at a dose of 8 mg IV immediately before the start of therapy. In addition, the successful use of Emetron for the prevention of nausea and vomiting in women in outpatient practice was noted.

Tropisetron

– a selective competitive antagonist of 5-HT3 receptors with a long duration of action (up to 24 hours). It is used to prevent nausea and vomiting, most often during chemotherapy, intravenously, at a daily dose of 5 mg. In patients with arterial hypertension, during the period of drug administration, blood pressure may increase, headaches, dizziness, increased fatigue and a feeling of tiredness, and dyspeptic disorders may occur.

Other drugs

A certain positive preventive effect of hydrocorticosteroids (dexamethasone)

during laparoscopic operations, allowing them to complement antiemetic therapy [6].

In our practice, to relieve nausea and vomiting on the operating table or in the recovery room in the immediate post-anesthesia period, the prescription of antiemetics, if necessary, is supplemented in some patients with inhalation of ammonia

, which causes a powerful airway reflex with simultaneous dilation of cerebral vessels.

At the same time, the gag reflex is “blocked” for some time and blood circulation in the area of the vomiting center and chemoreceptors of the trigger zone improves. When the gag reflex resumes, it is eliminated by repeated inhalation of ammonia. We were once again convinced of the effectiveness of this simple remedy by the example of one patient from the USA who wanted to have surgery in our country. She did not have a good relationship with American specialists: after 6 unsuccessful attempts to remove the uterine device and after each manipulation and anesthesia, she had a painful state of constant nausea and vomiting for 5–6 days. She came to our country for surgery. When prescribing her for abdominal surgery, the patient warned that she could not tolerate most anesthetic drugs and that she developed nausea and vomiting for several days.

Indeed, upon recovery from anesthesia and extubation, the patient experienced the urge to vomit, which was immediately eliminated by inhaling ammonia. Repeated urges that arose after 4–5 minutes were also extinguished with the help of ammonia. During transportation to the ward, repeated urges, which began to occur less and less frequently, were also stopped with ammonia. Then there was a long lull. After prescribing antihistamines and small doses of droperidol, the patient slept well throughout the night. And in the morning she wondered why she did not have nausea and vomiting, which remained a nightmare in her memory after previous manipulations. Thus, the gag reflex can be extinguished by a stronger reflex from the upper respiratory tract.

The correct choice of antiemetic therapy is essential to achieve the best results.

This is especially true when there is a high risk of prolonged nausea and vomiting, which is typical during radiation or chemotherapy, as well as during a complicated course of the postoperative period.

Literature:

1. Gelfand B.R., Martynov A.N., Guryanov V.A., Mamontova O.A.. Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting in abdominal surgery. Consilium medicum, 2001, no. 2, pp. 11–14.

2. Mizikov V.M. Postoperative nausea and vomiting: epidemiology, causes, consequences, prevention. Almanac MNOAR, 1999, 1, pp.53–59.

3. Mokhov E.A., Varyushina T.V., Mizikov V.M. Epidemiology and prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting syndrome. Almanac MNOAR, 1999, p.49.

4. Arif AS, Kaye AD, Frost E.. Postoperative nausea and vomiting. MEJ Anesthesia. 2001,16(2), p.127–154.

5. Watcha ME, White PF Postoperative nausea and vomiting. Its etiology, treatment and prevention. Anesthesiology, 1992, 77, pp. 162–184.

6. Ovchinnikov A.M., Molchanov I.V. Preventive antiemic effect of dexamethasone during endoscopic cholecystectomy. Bulletin of Intensive Care. 2001, no. 3, pp. 33–35.

Treatment of vomiting in oncology

Our doctors have learned to treat vomiting caused by chemotherapy sessions quite well. For its optimal treatment, a number of fundamental principles are currently used:

- It is necessary to predict the intensity of the pathology in advance and individually select combinations of therapeutic drugs;

- Take medications in advance and strictly at the prescribed time;

- Preference should be given to drugs administered intravenously or rectally;

- If the patient is nervous, give him appropriate medications;

- Include in the treatment regimen drugs that protect the mucous membrane;

- Monitor the level of trace elements in the blood and the required volume of circulating plasma.

Vomiting coffee grounds

If vomiting occurs in a conscious patient, then the penetration of some of it into the respiratory tract is minimal. In cases of loss of consciousness, the head must be turned to the side and tilted lower.

When vomiting stops, the mouth is thoroughly washed. Compensation for lost fluid occurs through water consumption.

First aid for cancer patients who are vomiting

If the vomiting is profuse and continuous and black in color, it is extremely important to provide first aid to the patient before the ambulance arrives. Put the patient to bed and try to provide him with maximum peace. Next, follow these instructions:

№1:

During an attack, carefully turn the patient onto his side and tilt his head slightly (this will prevent vomit from entering the respiratory system). After this, place a cold compress with ice on the cancer patient’s stomach, which will reduce discomfort and also stop internal bleeding, if any.

№2:

If there is a suspicion of internal bleeding in the lung area, a compress should be applied to the chest. To prevent severe dehydration, offer the patient warm drinks in the form of herbal infusions or sweet tea.

№3:

In order to maintain electrolyte balance in the body, it is better to use ready-made solutions, which should always be in a cancer patient’s medicine cabinet (for example, the “Regidron” solution, intended for oral administration, is effective). If possible, it is recommended to give medications that are available without a prescription (these can be antihistamines, for example, Suprastin, which will alleviate the patient’s condition).

Important:

Eating food immediately after the attack is over is strictly prohibited!

Vomiting and bleeding

A very alarming symptom of cancer is bleeding with vomiting. It can occur with either a large tumor or a small one if it is localized near a large vessel. Vomiting with bleeding is typical for the final stages of oncology; almost 2/3 of patients suffer.

If you take a form of cancer such as carcinoma, bleeding at first rarely manifests itself symptomatically. However, its danger does not decrease, especially with tumor infiltration. It has been observed that serious bleeding develops in 7 out of 10 patients. Every 9th patient experiences shock due to the fact that blood loss develops rapidly. 2 out of 10 experience wall perforation or tumor growth into neighboring organs.

Manifestations of blood loss

Blood loss leads to a sharp decrease in blood pressure, and as a result, a person experiences weakness. One can observe a waxy pallor on his face, his lips turn blue, and his heartbeat increases. The person sweats significantly, the sweat is sticky and cold. In some cases, loss of consciousness is observed.

Vomiting with blood is a very clear symptom of bleeding in the stomach.

Vomiting mixed with blood can be a signal of damage to blood vessels located in the respiratory tract, or an acute gastrointestinal disease.

These masses with food residues and an admixture of clotted blood have a disgusting odor.

The blood that enters the gastric lumen is fermented and becomes dark brown.

When blood passes through the intestinal tube, the color of the stool changes to black due to iron released from dead red blood cells. Often in a patient with cancer, the masses become similar to a tarry paste.

Thus, we can say that black stool and dark vomit are characteristic signs of bleeding that occurs in the stomach.

Vomiting may also be typical for obstruction of the gastric outlet or intestines.

Black stools, even if you feel well, are a reason to consult a doctor.

How can vomiting be dangerous for a cancer patient at stage 4?

If the vomiting does not contain blood in the masses, urgent specialist intervention is not required; it is enough to take special antiemetics and provide rest to the patient. However, in some cases, vomiting can lead to the death of the patient.

So, urgent intervention is required if you find blood clots in the masses, or the vomit has turned black. In this case, we can talk about internal bleeding, which, in the absence of timely medical intervention, can lead to death.

Life-threatening may also arise if vomiting continues for more than a day (more than three times a day), even while taking antiemetic medications.

Constant vomiting causes the following complications that are life-threatening for a cancer patient:

- Severe dehydration.

- The development of pathologies of the heart and blood vessels against the background of incessant nausea.

- Damage to the mucous membrane of the stomach and esophagus, leading to internal bleeding.

- The risk of thrombosis, which occurs due to blood clotting disorders (this is typical for cancer patients at the last stage).

Treatment of vomiting with blood

Vomiting with blood is a signal for urgent gastroscopy. It is on this basis that the cause of bleeding can be found and measures taken to eliminate it.

Similar measures can be carried out during endoscopic intervention - hypothermia, hemostatic agents, vascular coagulation.

Unfortunately, the risk of recurrence after endoscopy is quite high, so in most cases it is necessary to resort to surgery.

Resort to radical measures after endoscopy, i.e. removal of the stomach should not be done immediately, but after planned preparation of the patient for it, otherwise there is a significant risk of death.

The Onco.Rehab integrative oncology clinic is equipped with modern equipment and has highly qualified doctors to help you with your problems.