Perirectal fistula – a deep pathological channel (fistula) connecting the source of inflammation (tumor or abscess) with the lumen of the rectum and the external environment.

In almost 9 out of 10 cases, a rectal fistula is formed after acute paraproctitis.

Rectal fistula and paraproctitis are essentially different phases of the same disease. In most cases, as a result of an autopsy (spontaneous or with the help of a surgeon or coloproctologist), patients develop a rectal fistula or chronic paraproctitis. The beginning and root cause of rectal fistula is the presence of an internal micro-opening in the anal canal at the level of the anal crypts. Pararectal fistulas can also be a consequence of rectal tuberculosis or trauma.

1

Consultation with a proctologist

2 Consultation with a proctologist

3 Consultation with a proctologist

Fistula is a dangerous disease that can be avoided if you pay close attention to the symptoms of paraproctitis. A long course of the inflammatory process with perirectal fistulas can lead to serious consequences. Significant deformation of the anal canal and perineum occurs, cicatricial changes begin in the anal sphincter, which leads to anal sphincter insufficiency. In addition, the disease is characterized by a complication that also occurs with chronic anal fissure - cicatricial stricture (narrowing) of the anal canal. If left untreated for a long time, the fistula may become cancerous.

Types of rectal fistulas

Depending on the localization of the process, there are extrasphincteric, transsphincteric, intrasphincteric, rectovaginal fistulas of the rectum.

Intrasphincteric fistula (the fistula canal is located in the subcutaneous layer along the edges of the anus) is the simplest type of fistula, the initial stage of the disease, detected in 25-30% of cases. It has a direct course, the cicatricial process has not yet appeared.

A transsphyctic fistula passes partly through the sphincter, partly through the tissue. They make up more than 40% of the total number of identified fistulas. In the fistula tracts there are branches, purulent pockets, and scar processes develop in the surrounding tissues.

An extrasphyctic fistula is located deep in the skin layer, goes around the external sphincter of the rectum and opens on the skin of the perineum.

A rectovaginal fistula is formed between the lumens of the rectum and vagina.

Degree of complexity of rectal fistula

The mild degree is characterized by the presence of a direct fistula tract, the absence of cicatricial changes, infiltrates and pus.

Moderate degree: scar formation occurs near the internal opening of the fistula tract.

Moderate degree: a narrow opening is formed in the entrance fistula canal, there is no pus or infiltrates.

Severe degree , characterized by the appearance of multiple scars and the appearance of ulcers and infiltrates.

Symptoms

Symptoms depend on the location and cause of the fistula. The first symptoms are signs of a violation of the integrity of the colon wall:

- local abdominal pain,

- increase in body temperature,

- nausea,

- vomit,

- tachycardia,

- Possible bloating and retention of stool and gas.

After some time, a yellow discharge with a characteristic fecal (intestinal) odor appears in the area of the wound, drainage, or along the drainage. The amount of discharge can vary significantly and depends on the location and size of the fistula. The fistula can spontaneously close and open again. With copious discharge, the development of periwound dermatitis is possible.

Clinical manifestations of rectal fistula

Typically, patients complain of the presence of a fistula (wound) on the skin in the anus. Due to the discharge of pus and ichor, the patient has to wear a pad and perform water procedures several times a day. The discharge can cause itching and irritation on the skin.

Symptoms of rectal fistula

Symptoms of rectal fistula may be as follows:

- Formation of a wound in the anal area;

- discharge of blood, ichor from the wound, unpleasant odor;

- soreness, redness and irritation of the skin;

- compactions with pus along the rectal fistula;

- unstable general condition of the patient: restless sleep, irritability;

- disturbances of urination and stool.

Causes

If the intestinal fistula is congenital, then it appears due to abnormalities in the development of internal organs. This may be non-closure of the bile duct, anomalies of the intestinal-umbilical duct. Pathology can also appear due to mechanical damage to the intestinal walls due to injury or surgery. Moreover, it is the operation that causes intestinal fistulas in half of the cases.

Traumatic damage to the intestine can occur with shrapnel or knife wounds, or blows to the abdomen. But this rarely happens in peacetime. But complications after surgery are quite common. This may be intestinal obstruction, incorrectly placed sutures, the appearance of abscesses, or prolonged unjustified drainage. Sometimes the pathology is caused by medical errors, for example, due to improper removal of the appendix, opening of abscesses or intubation of the small intestine. It can also be rough probing or leaving gauze swabs in the abdominal cavity.

Intestinal fistulas can also appear without mechanical damage due to necrosis of the intestinal wall. The reason for this may be various factors:

- disturbance of blood supply;

- long-term inflammatory process;

- Crohn's disease;

- acute appendicitis;

- the appearance of diverticula in the intestine;

- presence of foreign bodies;

- intestinal obstruction;

- peritonitis;

- strangulated hernia;

- intestinal tuberculosis;

- actinomycosis;

- cancerous tumors.

Diagnosis of the disease

A conversation with the patient helps an experienced proctologist understand the nature of the disease. Already during the examination, the doctor may detect one or several holes near the anus, when pressed, the purulent contents of the rectal fistula are released.

1 Laboratory diagnostics in MedicCity

2 Stool test for blood

3 Colonoscopy

The patient is prescribed an examination, including the following types of tests:

- blood chemistry;

- general blood and urine analysis;

- microbiological analysis of purulent discharge to identify the infection that caused it;

- probing, which determines the length and tortuosity of the pathological canal;

- irrigoscopy (x-ray examination of the colon);

- ultrasonography;

- colonoscopy (endoscopic examination of the large intestine);

- fistulography (x-ray examination of fistulous tracts using a contrast agent);

- sigmoidoscopy (instrumental examination of the rectum and sigmoid colon);

- CT scan;

- sphincterometry (objective assessment of the functioning of the rectal sphincter).

Nutritional support for patients with digestive tract fistulas

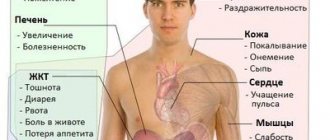

Why is the formation of fistulas a serious complication? Because in the vast majority of cases this is at least a long-term treatment, and at most a complication that can lead to death for the patient. For a doctor, the occurrence of this complication always requires the mobilization of his skill, time and mental strength. The results of treatment of digestive tract fistulas are directly related to the establishment of the causes of formation and the adequacy of the chosen treatment [1]. The causes of fistulas of the digestive tract are very diverse and are divided into several groups [1]: 1. caused by pathological processes in the abdominal cavity and its organs; 2. caused by tactical errors; 3. caused by technical errors and errors. Fistulas of the digestive tract are divided into two large groups: internal and external fistulas. Internal fistulas are characterized by the presence of a pathological anastomosis between two hollow organs. External fistulas are classified [1]: 1. By localization: • Esophagus • Stomach • Duodenum • Jejunum • Ileum • Cecum • Colon • Rectum • Biliary tract 2. By morphology: • Lip-shaped • Tubular 3. By degree formation: • Unformed: Fistula on a free loop, opening into a purulent wound Fistula, opening into a purulent wound Fistula, opening into a granulating wound Fistula, the mucous membrane of which is partially fused with the skin • Formed 4. By function: • Complete fistulas • Incomplete fistulas 5. By number: • On one loop • On different loops 6. Mixed fistulas: • Both small and large intestines 7. By complications: • Local (abscesses, phlegmons, purulent leaks, dermatitis, prolapse of the mucous membrane, enteritis, colitis, bleeding from fistula) • General (disorders of water-salt and protein metabolism, renal failure, exhaustion) 8. By the nature of the “spur”: • The “spur” is soft, will not stand in the fistula opening • The “spur” is soft, will stand in the fistula opening • “Spur” » rigid, stands in the fistula opening 9. The background against which the fistula develops and proceeds: • Peritonitis • Residual ulcers of the abdominal cavity • Partial intestinal obstruction • Eventration Also, fistulas of the digestive tract are classified according to the complex of anatomical structures involved or their physiological function [2] . The first type is digestive tract fistulas associated with several organs. The second type is fistulas localized in the anatomical projection of one organ. The third type is colonic fistula. The fourth type is characterized by the presence of a fistula tract opening into a defect with an area of more than 20 cm2 on the anterior abdominal wall. According to the volume of contents lost through the fistula in 24 hours [2]: 1. less than 200 ml; 2. from 200 to 500 ml; 3. more than 500 ml. All features given in this classification must be taken into account during treatment. As a result, the clinical picture will be more complete, and therefore the treatment plan will improve. During treatment, the clinical picture and features of the fistula may change, which should be taken into account in a timely manner. The presence of a fistula leads to incoordination of all organs and systems of the body. The severity of these disorders can be minimal, for example with fistulas of the colon, and extreme, sometimes becoming irreversible in the presence of high fistulas (duodenal, proximal jejunum). It should be noted that the severity of the condition with intestinal fistulas is determined not only by severe nutritional deficiency (from 55 to 90%), but also by the loss of digestive juices (gastric, intestinal, pancreatic, bile), as well as essential electrolytes, and severe hypovolemia. As a rule, hypovolemia is characterized by a deficiency of water and substances dissolved in it at normal plasma osmotic pressure - isotonic dehydration. Clinically, this condition is characterized by tachycardia, decreased blood pressure, loss of appetite, thirst, vomiting, and bloating. Changes in laboratory parameters are noted: an increase in the number of red blood cells, an increase in hematocrit. With intestinal fistulas, especially of the small intestine, there is a significant decrease in total protein, albumin, and albumin-globulin ratio. The decrease in these indicators is due to the following reasons: • insufficient supply of nutrients to the digestive system; • ineffectiveness of incoming nutrients to cover the energy and plastic needs of the body; • maldigestion due to loss of enzymatic function; • malabsorption; • violation of the protein-synthesizing function of the liver; • albuminuria. Hypoelectrolythemia is manifested by a decrease in the level of potassium, calcium, and magnesium in the blood serum. The level of sodium and chlorine in patients remains within normal limits in the vast majority of cases. With fistulas of the duodenum and small intestine, metabolic acidosis most often develops, which is caused by the loss of bicarbonate. With gastric fistulas, on the contrary, metabolic alkalosis often develops. It must be remembered that with intestinal fistulas, pathological changes also occur in many internal organs: liver, adrenal glands, kidneys, pancreas. In the liver, degeneration of hepatocytes and swelling are most often observed. Glycogen reserves also decrease. All this leads to disruption of the synthesis of albumin and prothrombin, and a decrease in antitoxic function. Due to thinning of the adrenal cortex, patients experience hypotension and tachycardia. The changes that develop in the kidneys during intestinal fistulas are called “intestinal wasting nephrosis” [1]. It is also necessary to remember that the constant flow of intestinal contents has a depressing effect on the mental state of the patient. Moreover, this condition is quite often aggravated by adjunctive dermatitis. Thus, the pathophysiological disorders that occur with fistulas of the digestive tract are very diverse and, in fact, affect the main vital systems of the body. The problem of nutritional support for patients with intestinal fistulas has not been solved unambiguously to date. Thus, most clinicians decide to transfer the patient to parenteral nutrition with the complete exclusion of oral nutrition. However, there is another point of view, according to which the patient should receive adequate nutrition per os, avoiding only the consumption of highly juiced foods, in combination with parenteral nutrition. In the 40–50s of the XX century. a diet was proposed that contained little fiber [N.K. Müller, 1944], the main ingredients were: fish (mashed), cottage cheese, eggs (omelet), butter, white bread, crackers, dry biscuits, steep porridge (rice, semolina). For sweet dishes, jelly, jelly, and mousses were recommended. This diet is designed for complete absorption of food in the small intestine. Thus, clinicians used parenteral nutrition and oral nutrition with or without parenteral nutrition. Today, for fistulas of the digestive tract, both parenteral and enteral nutrition (specialized enteral mixtures) are used. Parenteral nutrition used in patients with intestinal fistulas not only maintains a positive nitrogen balance, but also helps to increase total protein and albumin in the blood serum, and sharply reduces the secretion of secretions from organs involved in digestion, thereby promoting spontaneous closure of the fistula. This is supported by the data of Sanjay SN et al. [3] and other authors. Edmunts et al. [4] analyzed 157 patients with enterocutaneous fistulas and reported a mortality rate of 59% despite intensive therapy but without the use of nutritional support technologies. A study by Chapman et al. [5] shows that as a result of the use of parenteral nutrition (3000 kcal/day) in 56 patients with enterocutaneous fistulas, the mortality rate was 12%, closure of the fistula was noted in 89% of patients. Of interest is the analysis of 404 patients with enterocutaneous fistulas conducted by Soeters [6], over three periods: the first from 1945 to 1960, the second from 1960 to 1970, the third from 1970 to 1975. As a result, it was noted that during the first period the mortality rate of patients was 48%, while in the second period the mortality rate of patients was 15%. The difference in data in these periods is explained by the use of more adequate parenteral nutrition technologies. When analyzing the indicators of the third period, an increase in the incidence of spontaneous closure of the fistula was noted. According to Traverso LW et al. [7] the use of parenteral nutrition technologies can reduce the volume of intestinal losses through the fistula by 30–50%, thereby reducing the loss of enzymes and reducing catabolism. Based on the above data, it may seem that parenteral nutrition is the most preferred method of nutritional support for patients with digestive tract fistulas. However, its use can lead to such serious complications as: • bacterial translocation; • catheter-associated infection; • metabolic disorders (overload or, conversely, lack of certain nutrients). As a result, there is an even greater increase in losses through the fistula [8–10]. In addition, parenteral nutrition does not reduce basal or cephalic secretions, and long-term use of parenteral nutrition may lead to stimulation of gastric and intestinal secretions, thereby exacerbating nutritional deficiency. It is indisputable, according to most researchers [11,12], that enteral nutrition is the preferred method of nutritional support as it is more effective for correcting catabolism, as well as promoting the preservation and regeneration of the intestinal wall [11,12]. It must be remembered that certain enteral mixtures contain glutamine, arginine, nucleotides, omega-3 fatty acids, which leads to restoration of the integrity of the intestinal mucous layer, as well as faster closure of the fistula [12]. Enteral nutrition can also be used in cases of heavy loss of intestinal contents through a fistula. Proof of this is the study by Levy et al. [8], conducted on 335 patients with enterocutaneous fistulas. The volume of losses through the fistula averaged about 1350 ml/day. As a result of the use of enteral nutrition, the fistula closure rate was 85%. On average, colonic fistulas close in 30–40 days, ileal fistulas in 40–60 days, and small intestinal fistulas in 50 days. However, the duration can vary from 10 weeks to 13 months [13]. The choice of one or another nutritional support technique is mainly based on the location of the fistula. If the fistula is associated with the pancreas, jejunum, ileum, proximal part of the small intestine and is “highly productive,” then parenteral nutrition is more often used. In the case when the fistula is associated with the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, distal ileum, colon, it is recommended to resort to enteral nutrition [3,14]. Thus, when choosing a method of nutritional support, it is necessary to take into account the location of the fistula and, if it is possible to use the enteral method of nutritional support, strive to use it, since this is a more effective, safe and accessible method of nutritional support. According to Waitzberg DL et al. [15], every day a patient with a fistula loses approximately 75 g of protein, 12 g of nitrogen plus enzymes and intestinal chyme. Therefore, most researchers [13,15,16] believe that the need for patients with a “low-productive” fistula is from 1 to 1.5 g of protein per 1 kg of weight per day, for “high-productivity” fistulas - from 1.5 to 2. 5 g of protein per 1 kg of weight per day. Nutritional regimens must necessarily contain vitamins and minerals. Particular attention should be paid to the level of vitamin C, zinc, copper, folic acid, and vitamin B12. Due to the fact that in Russia parenteral nutrition is most often used in the treatment of patients with intestinal fistulas, in our article we would like to present the results of treatment of a patient with a fistula in the area of gastroenteroanastomosis. Clinical example Patient D., 85 years old, was admitted as planned for surgical treatment to one of the regional hospitals. During the examination, the patient’s diagnosis was verified: gastric antral cancer, T3N2M0, histology – moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma. The surgical intervention was performed in the scope of subtotal resection according to Billroth II in the Hofmeister-Finsterer modification. Clinical and laboratory parameters of the patient are shown in Table 1. In the postoperative period, the patient received parenteral nutrition at the rate of: protein - 0.8 g per 1 kg of weight per day (Infezol 100), energy - 20 kcal per 1 kg of weight per day, infusion - transfusion therapy, antibacterial therapy. Nevertheless, the patient’s condition progressively worsened: hemodynamic parameters and protein pool decreased, contact with the patient became more and more difficult due to his lethargy. On the 10th day, gastric discharge appeared from a pinhole on the anterior abdominal wall, in the projection of the gastroenteroanastomosis. Emergency radiography with water-soluble contrast was performed, and failure of the anterior wall of the gastroenteroanastomosis with the formation of a fistula was detected. A pronounced adhesive process contributed to the rapid delimitation of the incompetent esophageal anastomosis from other parts of the abdominal cavity. The nutritional support scheme included parenteral nutrition Infezol 100 for 7 days, followed by a transition only to enteral tube feeding in a volume of 2.5 l, with a density of 1.0 kcal/ml. The feeding tube was installed endoscopically. The drugs used for parenteral nutrition were (Infezol 100 – 1000.0 ml; MCT/LCT fat emulsion 10% – 500.0 ml; glucose 20% – 600.0 ml). The patient's condition progressively improved. Nutrition indicators have improved: anthropometric, dynamometric, biochemical, psychological and nitrogen balance indicators. Clinically, the patient became more active, clearly positive dynamics were noted, the regime expanded to ward, and then general. The fistula closure time was 30 days. Thus, nutritional support for patients with intestinal fistulas should be an obligatory component of conservative therapy.

Literature 1. Bogdanov A.V. Fistulas of the digestive tract. M., 2001. 2. Konzell K., et al. "Managing the challenges of enterocutaneous". J. Wound Care Canada, vol.1. n.1, 2002. 3. Sanjay SN et al. "Nutritional support in enterocutaneous fistula". Center for research on nutrition support system. 4. Edmunds LH et al. "External fistulas arising from GI tract." Ann.Surg.1960; 152; 445–471. 5. Chapman R. et al. "Management of intestinal fistulas". Am.J.Surg. 1964; 108: 157–164 6. Soeters PB et al. “Review of 404 patients with gastrointestinal fistulas. Impact of parental nutrition". Ann.Surg.1979; 190(2); 189–202. 7. Traverso LW et al. "The effect of total parental nutrition or elemental diet on pancreatic proteolytic activity and ultrastructure." J. Parenteral Enteral nutrition 1981; 5:496–500. 8. Levy E. et al. “High-output external fistulae of the bow smallel: management with continuous enteral nutrition.” Br.J.Surg. 1989; 76:676–679. 9. Rombeau JL et al. "Enteral and parenteral nutrition in patients with enteric fistulas and short bowel syndrome." Surg. Clin. North. Am. 1987; 67:551–571. 10. Alexander JW et al. "Bacterial translocation during enteral and parental nutrition." Proc. Nutr. Soc. 1998; 57:389–393. 11. Baigrie RJ et al. “Enteral versus parental nutrition after oesophagogastric surgery. A prospective randomized comparison". Aust. NZ. J. Surg. 1996; 66:668–670. 12. Meguid MM et al. "Management of patients with gastrointestinal fistulas." Surg. Clin. North. Am. 1996; 76:1035–1080. 13. Conter RI et al. "Delayed reconstructive surgery for complex enterocutaneous fistulae." In Bryant R (ed.), Acute and Chronic Wounds. St. Louis: Mosby. 1988; 322. 14. Gonzales–Pinto I. et al. "Optimizing the treatment of upper gastrointestinal fistulae". J. Gut 2001; 49:21–28. 15. Waitzberg DL et al. "Postoperative total parental nutrition". World J. Surg. 1999; 23:560–564. 16. Berry SM et al. "Classification and pathophysiology of enterocutaneous fistulas". Surg. Clin. North. Am. 1996; 76:1009–1018.

Treatment of rectal fistula

Don’t waste time; at the first symptoms of proctological diseases, consult a coloproctologist! This way you can avoid complications, the most dangerous of which is the malignant degeneration of chronic paraproctitis (fistula)!

The treatment regimen for rectal fistula is determined by a coloproctologist as a result of an examination, but today these are only surgical methods. They allow you to radically remove the entire fistula tract and cure the patient of rectal fistula once and for all. During the operation of excision of a rectal fistula, as a rule, concomitant diseases are removed - hemorrhoids, anal fissure, etc. Thus, treatment for a rectal fistula allows the patient to get rid of a whole list of unpleasant diseases in one fell swoop.

Postoperative period

For several days after surgery, the patient needs careful monitoring by a doctor. Treatment continues and includes taking analgesics and antibiotics. To more quickly relieve inflammation and heal sutures, baths with a solution of antiseptics - furatsilin and potassium permanganate, and dressings with antibacterial ointments are used. To reduce the risk of complications, patients are not recommended to lift heavy objects for several months after the fistula excision procedure.

During the healing process of the suture, it is recommended to change your diet. On the first day after it, you can only eat liquid foods - kefir, water, a little boiled rice. With this menu, in the first days there will be no stool, which will reduce trauma to postoperative wounds. In subsequent days, the menu gradually includes boiled vegetables and fresh fruits, grain products and cereals, fermented milk products and plenty of drinking. If necessary, you can take laxatives.

Surgery to remove rectal fistula

To better prepare for surgery, your doctor may prescribe antibiotics and topical pain relievers. During the operation to remove a rectal fistula, the following manipulations are performed: excision of the rectal fistula, opening and cleaning of purulent pockets, suturing the sphincter, moving the rectal mucosa to eliminate the internal hole.

1 Surgery to remove rectal fistula

2 Surgery to remove rectal fistula

3 Surgery to remove rectal fistula

The choice of surgical treatment method depends on the type of fistula, its location, the degree of scarring, the presence of ulcers and infiltrates.